study-committee-report

study-committee-report

study-committee-report

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

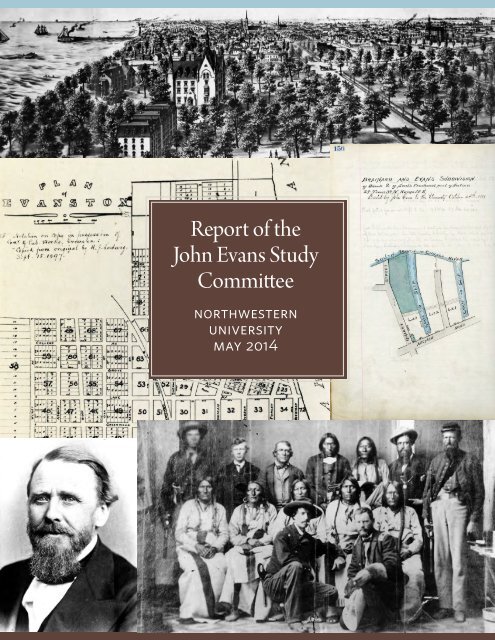

Report of theJohn Evans StudyCommitteeNorthwesternUniversityMay 2014

ContentsReport of the Northwestern UniversityJohn Evans Study CommitteeNed Blackhawk(Western Shoshone)Professor of History, AmericanStudies, and Ethnicity, Race,and MigrationFaculty Coordinator, YaleGroup for the Study ofNative America (YGSNA)Yale UniversityLoretta FowlerProfessor Emerita ofAnthropologyUniversity of OklahomaPeter HayesProfessor of History andChair of the DepartmentTheodore Zev Weiss HolocaustEducational FoundationProfessorNorthwestern UniversityFrederick E. HoxieProfessor of HistorySwanlund Professor ofAmerican Indian StudiesUniversity of Illinois atUrbana-ChampaignAndrew KoppelmanJohn Paul Stevens Professorof LawProfessor of Political ScienceNorthwestern UniversityCarl Smith, ChairFranklyn Bliss SnyderProfessor of English andAmerican Studies andProfessor of HistoryNorthwestern UniversityElliott WestAlumni DistinguishedProfessor of HistoryUniversity of Arkansas,FayettevilleLaurie ZolothProfessor of Religious StudiesProfessor of Bioethics andMedical HumanitiesNorthwestern UniversityAlexander GourseJohn Evans CommitteeResearch FellowDoctoral Candidate,Department of HistoryNorthwestern UniversityChapter One: Introduction 5Chapter Two:The Life and Career of John Evans 11Chapter Three:Colorado Before Sand Creek 37Chapter Four: The Road to Sand Creek 58Chapter Five: The Aftermath 76Chapter Six: Conclusions 85Notes 96Links to Key Documents and Websites 111Acknowledgments 113

Chapter One: IntroductionOn the clear and frozendawn of Tuesday,November 29, 1864,more than seven hundredheavily armed United Statescavalry approached an encampmentof Cheyenne and Arapaho Indiansby a large bend in a dry riverbedcalled Sand (or Big Sandy) Creek,in an open and isolated spot onthe high plains of southeasternColorado Territory. The sleepingIndians had no inkling of what wasabout to happen and had posted noguards. A few weeks earlier, followinga spring and summer of sometimesdeadly encounters betweenthe territory’s Native people andits settlers and soldiers, the inhabitantsof the camp had declared theirpeaceful intentions and surrenderedat Fort Lyon, on the Arkansas River about fortymiles to the southwest of where the Cheyennes andArapahos had pitched their tipis. The fort’s commander,Major Scott Anthony, who was now partof the advancing force, had directed the Indians tothis site, and they thought they had been assured asafe refuge.The soldiers had ridden all night from FortLyon. Most of them were members of the ThirdColorado Cavalry, a volunteer regiment formed afew months earlier to confront hostile Indians. 1 TheThird was nearing the end of a period of servicelimited to one hundred days, presumably enoughtime to deal with the danger. Accompanying thesetroopers were about 125 men from the veteran FirstCavalry. At the head of this combined force wasDetail from the elk hide painting by Northern Arapahoartist Eugene Ridgely Sr. (1926–2005) of the Sand CreekMassacre. Note the depiction of Black Kettle raising the twoflags to indicate to the attacking soldiers that the camp ispeaceable. (©1994 Elk Hide Painting, The Sand CreekMassacre, Eugene Ridgely Sr., Northern Arapaho, Courtesyof the Ridgely Family. ©1996 Photograph, Tom Meier)Colonel John Chivington, commanding officer ofthe Military District of Colorado, headquartered inDenver. A hulking bully of a man, Chivington wasa Methodist minister who had taken up the swordwhen the South rebelled. He had won glory for hisrole in repelling a Confederate attempt to invadeColorado in 1862 but had accomplished little sincethen to advance his goal of promotion to brigadiergeneral.Introduction 5

Upon arriving at a rise overlooking the encampment,Chivington directed his men to strap theircoats to their saddles to allow themselves morefreedom of movement in battle, and he dispatched afew companies to get between the Indians and theirgrazing ponies. Then he stirred up the troopers byreminding them of the brutal killings of white settlerfamilies by NativeThe soldiers became a savage,American warriorsundisciplined, and murderous since the spring—mob. Some ran down individuals“Now boys, I shan’tsay who you shall kill,or small groups of fleeing Indians, but remember ourexecuting helpless women and murdered womenand children”—andchildren at point-blank rangehe ordered them toand mutilating the victims.charge. 2The ferociousattack, backed by shells from two twelve-poundmountain howitzers—the only time the U.S. Armyemployed such heavy artillery against Indians inColorado—took the encampment entirely bysurprise. 3 Some who had heard the hoofbeats of theheavy cavalry horses at first mistook them for buffalo.While the attacking force did not greatly outnumberthe Indians, the Cheyennes and Arapahoswere far less armed, and many younger warriorseither had decided not to join this group or hadgone hunting for the buffalo they would need tosurvive the winter. The majority of those remainingwere women, children, and elderly men.The Indians reacted to the merciless onslaughtwith a mixture of confusion and terror. Cheyennechief Black Kettle, the most outspoken advocate ofpeace with the American settlers, thought that thesoldiers did not realize that the camp was friendly.He desperately retrieved the United States flagthat former Commissioner of Indian Affairs AlfredGreenwood had given him a few years earlier as asymbol of amity and hoisted it to the top of his tipi,along with a white banner that he had been toldwould signal to soldiers that his camp was peaceable.George Bent, the mixed-race son of the traderWilliam Bent and his Cheyenne wife Owl Woman,was in the encampment and experienced the nightmarefirst-hand. Bent later recalled that anotherhighly respected Cheyenne leader, White Antelope,“when he saw the soldiers shooting into the lodges,made up his mind not to live any longer,” since hehad not only trusted the soldiers himself but alsohad persuaded his people to do so. White Antelope“stood in front of his lodge with his arms foldedacross his breast, singing the death-song:‘Nothing lives long,Only the earth and the mountains.’” 4Some Indians fell to their knees and beggedfor mercy. Others fled to the north and west or upSand Creek for as far as two miles before hastilydigging protective pits in the banks of the riverbed.The violence lasted into the middle of the afternoon,producing scenes of unspeakable brutality.The soldiers became a savage, undisciplined, andmurderous mob. Some ran down individuals orsmall groups of fleeing Indians, executing helplesswomen and children at point-blank range and mutilatingthe victims.Captain Silas Soule of the First Cavalry, whohad drawn Chivington’s wrath the evening beforewhen he fiercely objected to the colonel’s plans,ordered his men not to fire. Lieutenant JosephCramer also refused, in his words, “to burn powder.”Soon after the massacre, they each wrote toMajor Edward “Ned” Wynkoop, Anthony’s predecessorat Fort Lyon, of the horrors they beheld.Soule told of a soldier who used a hatchet to chopoff the arm of an Indian woman as she raised it inself-defense and then held her by the remainingarm as he dashed out her brains. Another woman,after realizing that begging for her family’s lives wasuseless, “cut the throats of both [her] children, andthen killed herself.” Yet another, finding that herlodge was not high enough for her to hang herselffrom a suspended rope, “held up her knees andchoked herself to death.”All the dead Indians’ bodies were “horriblymutilated,” Soule continued. “One woman was cutopen, and a child taken out of her, and scalped.”Soule also <strong>report</strong>ed, as did others, that the soldiersslashed away the genitals of women as well as men,including White Antelope and his fellow chief WarBonnet, and displayed them as trophies. The perpetratorsincluded officers as well as enlisted men.These atrocities took place not only in the passionof battle but also in the calm of the following6 Chapter One

A participant at the dedication of the Sand Creek MassacreNational Historic Site on April 27, 2007, waves anAmerican flag and a white flag in commemoration ofthe flags that Black Kettle raised to signal the advancingtroops that the people in the encampment were peaceable.(Courtesy Post Modern Company, Denver, CO).Yellow Shield, One Eye, and Yellow Wolf. Onlytwenty months earlier, Standing in the Water andWar Bonnet had been part of a delegation of NativeAmericans who met with President AbrahamLincoln at the White House. Black Kettle, mistakenlylisted by Chivington as killed, miraculouslysurvived and even rescued his badly wounded wife,Medicine Woman. 7The death of so many key figures created aterrible void in tribal leadership. Since these leadersall favored peace with the American authorities, thekillings convinced many southern Plains Indiansthat armed resistance was now their only optionand turned Black Kettle into an object of ridiculeand animosity among his people. Far from endingthe Indian threat, Sand Creek ignited an extendedperiod of bitter warfare on a larger, costlier, anddeadlier scale than before.The devastating consequences of the massacrefor the victims are impossible to overstate. SandCreek was a deep wound that would never close,a profound insult as well as a grievous injury. Theslaughter became seared into the collective memoryof the Cheyennes and Arapahos as one of manyinstances of betrayal, humiliation, and loss at thehands of the United States that continue to thepresent. Although the attack occurred almost 150years ago, it remains a palpable presence and forcein these communities today, a reminder never totrust American authorities. Such feelings pervadethe oral histories recorded by elderly descendantsof Indians in the encampment and collected aspart of the preparatory <strong>study</strong> for the Sand CreekMassacre National Historic Site, which Congressauthorized in 2000 and the National Park Servicededicated seven years later. 8Southern Cheyenne Lyman Weasel Bear,for instance, recalled his mother’s descriptionof a grandfather scalped alive, while SouthernCheyennes Emma Red Hat and William Red Hat Jr.spoke of soldiers who, as Soule witnessed, slashedopen a pregnant woman’s belly “and took theCheyenne child out and cut his throat.” The descendantsrepeatedly spoke of the burden of sadness.Northern Cheyenne Nellie Bear Tusk said that hergrandmother “would always cry” as she told herstory. Northern Cheyenne Nelson Tall Bull’s grandmotherwould start to reminisce “and then not beable to continue because each time she began tosay something about [Sand Creek] she would startcrying and never finish.”Northern Cheyenne Dr. Richard Little Bearobserved, “We still live with it. Some peoplewonder why we have a hard time with white peopleand white organizations and white systems. That’sbecause those have been very destructive to usas a tribe of people.” 9 To help assuage such painfulfeelings among the living while honoring thedead, since 1999 descendants of the Sand CreekMassacre victims and people who sympathizewith them have participated in an annual SpiritualHealing Run/Walk in late November that extendsfrom the massacre site to Denver.The Sand Creek Massacre is a shameful stainon our country, on the social relationships that arethe basis of our democracy, and on our aspirationsto be a just society. This is not just the retrospective8 Chapter One

As Ari Kelman explains in A Misplaced Massacre:Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek (2013),Kiowa County (CO) installed this marker at the SandCreek Massacre site on August 6, 1950. The marblemonument includes the head of a warrior in profileabove the inscription, “Sand Creek Battle Ground, Nov.29 & 30, 1864.” A more recent National Park Serviceinterpretive sign is in the background. At the same timethe Kiowa County marker was unveiled, the ColoradoHistorical Society (now History Colorado) placed asecond marker, a marble obelisk, by the highway closeto the nearby town of Chivington. (John Evans StudyCommittee, 2013)view of Native Americans and their present-daysympathizers. General Nelson A. Miles, whosecareer stretched from the Civil War to the Spanish-American War and who became CommandingGeneral of the U.S. Army on the strength of hisexploits defeating Indians on the plains, observedin his memoirs, “The Sand Creek massacre is perhapsthe foulest and most unjustifiable crime in theannals of America.” 10How could this happen? Beyond JohnChivington and the men of the Third, what individuals,actions, and circumstances caused thisatrocity? Who might have prevented it, but did not?What were the consequences?The subject of this <strong>report</strong> is where John Evans(1814–1897) belongs in the answers to these questions.In the spring of 1862, President AbrahamLincoln appointed Evans Territorial Governor ofColorado and its ex officio Superintendent of IndianAffairs. Evans served until the summer of 1865,when he resigned after a Congressional <strong>committee</strong>demanded his ouster because of the Sand CreekMassacre and Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson,followed suit.Northwestern University’s interest in Evans’srelationship to Sand Creek stems from his prominentplace in the institution’s history. Evans wasone of the nine civic-minded Methodists whogathered in 1850 for the purpose of establishingthe University, and he was the central figure overthe next few years in realizing their vision. Inrecognition of this, they named the town in whichNorthwestern is located after him. They also electedhim president of the University’s Board of Trustees(and head of the Board’s powerful executive <strong>committee</strong>),a position he held continuously for overforty years. Although Evans attended only a smatteringof meetings in person following his departurefor Colorado in 1862—he continued to residein Denver after he resigned the governorship—heremained a significant presence as a donor andfinancial adviser. He was without question a warmfriend of the University, which over the years hashonored him more than any other person connectedwith the history of Northwestern. His nameis on the alumni center and several professorialchairs. Writing in 1939, University President WalterDill Scott declared that Evans “has had a greaterinfluence on the life of the City of Evanston andof Northwestern University, and has done more tocreate our traditions and to determine the line ofour development, than any other individual.” 11The glowing language of the University’scommemorations of Evans and its complete silenceregarding the horrifying massacre that sullied hiscareer as territorial governor have aroused debatein recent years. Some students, faculty, and othercommunity members have expressed concern thatIntroduction 9

the University has glorified someone who does notdeserve such treatment. Conversely, others havewondered whether the critics are subjecting Evansto the sort of ahistorical character assassination thatjudges a person in the past by the standards of thepresent.In the winter of 2013, Northwestern UniversityProvost Daniel Linzer responded by appointingour <strong>committee</strong> of eight senior scholars, four fromwithin and four from outside the University, toexamine in detail Evans’s role in the massacre.Provost Linzer also asked the <strong>committee</strong> to try todetermine whether any of Evans’s wealth or hisfinancial support to Northwestern was attributableto his policies and practices regarding NativeAmericans in Colorado while he was in office.Our investigation is not a unique effort—indeed, it occurred simultaneously with similarinitiatives by the University of Denver, in whosehistory John Evans figures at least as importantlyas in Northwestern’s, and by the United MethodistChurch, in which both he and Chivington wereactive and prominent. The 150th anniversary ofthe Sand Creek Massacre (and of the University ofDenver) in 2014 partly explains the resurgence ofinterest in this matter, but all three inquiries are alsopart of a trend by governments and institutions—notable among the latter are institutions of higherlearning—to acknowledge and come to termswith troubling aspects of their pasts, including thesources of their funding. 12Our <strong>report</strong> consists of six chapters, includingthis introduction. Chapter Two presents anoverview of Evans’s life and his relationship withNorthwestern University. Chapter Three describesthe historical context of the massacre, includingthe settlement of Colorado, the history of U.S. landacquisition from Native Americans, the responsesof the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes to the arrivalof American settlers and soldiers, and the effects ofthe Civil War on Colorado Territory. Chapter Fourtraces the course of events during Evans’s governorshipthat led to the Sand Creek Massacre. ChapterFive discusses the aftermath of the massacre,focusing on the public outcry, Evans’s defense of hisactions, and his resignation. Chapter Six states the<strong>committee</strong>’s conclusions regarding John Evans andthe Sand Creek Massacre.The Sand Creek MassacreNational Historic Site.The view is toward thenorth, from the bluffsoverlooking the location ofthe encampment. The lineof trees marks the currentlocation of Sand Creek. TheThird Cavalry attackedfrom the south, and theIndians who survived fledto the north and northwest.(John Evans StudyCommittee, 2013)10 Chapter One

Chapter Two: The Life and Career of John EvansTo a remarkable extent, John Evansembodied the major developments of histimes. He was a physician and professorof medicine during the rise of the professionsin the United States, the leading advocate forand first superintendent of a hospital for the mentallyill in the era of asylum building, a Mason whenfraternal orders were rapidly expanding, a founderof universities as the number of institutions ofhigher learning in America greatly increased, anactivist councilman in the city that was the emblemof nineteenth-century American urbanization, alay Methodist leader in the period when majorProtestant sects in this country established themselvesas national organizations, a stalwart of theRepublican Party who participated in AbrahamLincoln’s rise to the presidency, a builder of railroadsduring the transportationrevolution, and, in multiple ways,an entrepreneur in the age ofenterprise. He also personifiedthe westward movement of thecountry’s settlers, first to theformer Northwest Territory andthen to the Great Plains andthe Rockies, with the concomitantdisplacement of NativeAmericans and disruption oftheir culture.John Evans was more thana representative man, however.In virtually all he did, he was anexceptionally ambitious, influential,and capable figure who consistentlysought and frequentlyattained demanding positions ofleadership. His combination ofIn virtually all he did, he wasan exceptionally ambitious,influential, and capable figure whoconsistently sought and frequentlyattained demanding positions ofleadership. His combination ofintelligence, ingenuity, hard work,and practicality place him in thebest traditions of the self-madeAmerican achiever. As such, hesought to combine doing well withdoing good, to make his worldlyactions serve a broader and higherpurpose than self-interest.intelligence, ingenuity, hard work, and practicalityplace him in the best traditions of the self-madeAmerican achiever. As such, he sought to combinedoing well with doing good, to make his worldlyactions serve a broader and higher purpose thanself-interest. 1In the Old NorthwestJohn Evans was born on March 9, 1814, in a logcabin near the village of Waynesville, Ohio, locatedbetween Dayton and Cincinnati. He was the firstof the eleven children (nine lived past childhood)of David and Rachel Evans. His father was a farmerwho became a modestly prosperous toolmaker,storekeeper, and real estate investor. David Evansopposed his son’s ambitions to be a doctor, butJohn persisted. He received his M.D. degree fromCincinnati College in 1838, thesame year he married HannahCanby in Bellefontaine, Ohio,about sixty-five miles north ofWaynesville.While they were courting,John wrote to Hannah that “in thewhole range of scientific pursuitsthere is no one path that leads to awider range for contemplation, nora more fruitful source of investigationthan the medical profession.”In the same letter he assured herthat a career in medicine did nottend, as some believed, towardimpiety. 2 Evans was well aware,however, that his profession hadto provide him a living as wellas a calling. After disappointingattempts to set up a practice inThe Life and Career of John Evans 11

small-town Illinois and then back in Ohio, he establisheda successful medical partnership in Attica,Indiana, on the Wabash River about sixty milesnorthwest of Indianapolis.Evans’s Indiana years were critical to the developmentof his professional goals, organizationalskills, and religious faith. He became the drivingforce in the authorization by the state governmentof the Indiana Hospital for the Insane, to be locatedin Indianapolis. In 1845, he was named the institution’sfirst superintendent, whoseduties included directing thebuilding’s construction. Evanstoured similar institutions to learnthe latest thinking on humanetreatment, and his resulting workdrew the praise of the famed antebellumreformer Dorothea Dix.When he was still living in Attica,he joined Lodge No. 18 of theMasons, and he was among theorganizers of the Marion Lodgeof Indianapolis. 3Just before he was appointedsuperintendent, Evans hadaccepted a position teaching atRush Medical College (now partof Rush University) in Chicago,founded eight years earlier. Sincehis duties there occupied only aportion of the year, Evans tried tojuggle the two jobs, but in 1848he resigned from the hospital and moved his familyfrom Indianapolis to Chicago.Evans maintained a lifelong respect for thebeliefs of his Quaker parents, though he followeda different faith. The crucial event in his religiouslife occurred in 1841, when Methodist Episcopalminister Matthew Simpson came to Attica fromGreencastle, Indiana, to promote Indiana Asbury(now Depauw) University, which had been startedin 1837. Simpson, only three years Evans’s senior,had been chosen the institution’s first president.He was on his way to becoming the MethodistChurch’s most prominent bishop of the middledecades of the nineteenth century, a highlyregarded voice on secular issues as well as churchmatters. Eager to advance Methodism in Americaand, in keeping with that goal, the election andappointment of Methodists to public office,Simpson developed relationships with many politicians,including Abraham Lincoln, at whose funeralhe delivered the eulogy.Evans heard Simpson preach in an unfinishedmill and was so deeply affected that he traveled fourmiles the following evening to listen to Simpsonagain. “He is the first man that ever made my headswim in talking,” Evansrecalled almost fifty yearslater. “He carried his eloquenceup to a climax andI had to look around to seewhere I was.” 4 Soon Johnand Hannah were ardentMethodists, devoted followersand warm friends ofSimpson, with whom Evansremained close until thebishop’s death in 1884.The talk that so captivatedEvans in Attica wasa version of the address oneducation Simpson deliveredwhen he was inauguratedas president of IndianaJohn Evans as a young man. (Northwestern Asbury. In it SimpsonUniversity Archives)maintained that America’sindividual and nationalcharacter depended on thequality of instruction its young people received. Heargued that learning possesses an ethical dimensionthat encourages the individual to “cherish and cultivatedispositions for enlarged efforts to amelioratethe condition of man.” There was no more importantplace to build educational institutions than innew communities in emerging parts of the country,since these embodied America’s future. “In ournational councils,” Simpson declared, “the voice ofthe West [by which he meant what we now call theUpper Midwest] is heard with delight; it may nothave the elegance of the East, but it has the boldnessof native sublimity.” 5Evans did not explain why the content ofSimpson’s address, as opposed to the effectiveness12 Chapter Two

of the delivery, moved him so deeply. But one candetect the influence of the minister’s words in therest of Evans’s life. Simpson’s theology rested on thefoundational traditions of Methodism, emphasizingthat vigorous and constructive social engagement,when combined with conscientious self-discipline,was a form of religious practice. This idea appealedto Evans, a pragmatic man whose unfailing dedicationto the Methodist Church over the decadesconsisted mainly of dutiful activity rather than profoundreflection. His conversion did not so muchchange his behavior as convince him that workinghard and fostering beneficialsocial institutions affirmed a person’sspiritual development andgave worldly evidence of grace.Evans relocated to Chicagoat a momentous time. In the late1840s, the city was emergingas the country’s great inlandcommercial center, the linchpinbetween the industrializing Eastand the agricultural West. Evansbecame part of the gatheringmultitude of newcomers who allied their hopesto the young metropolis’s possibilities. Thanks toindividuals of similar ambition, imagination, andtalent, Chicago would soon be the world’s leadingcommodities market and railroad center. 6 In manyrespects, however, the city was still very much awork-in-progress with a rough-edged and improvisedculture. It had been incorporated only elevenyears before Evans arrived and was still markedby more of the “boldness” to which Simpsonalluded than “native sublimity.” As late as 1830,Chicago was a mere outpost with a local culturethat included the families of French trappers andtraders who had married into local Indian tribes.As recently as 1833, following the Black Hawk War,Chicago had hosted a council between governmentofficials and Native Americans that resultedin a series of treaties calling for the cession of largetracts of Indian land and the removal of many tribesto the West.Evans quickly became a prominent memberof the “Old Settler” generation of Chicagoans whoarrived before 1850. They moved there primarily inHis conversion did not somuch change his behavior asconvince him that working hardand fostering beneficial socialinstitutions affirmed a person’sspiritual development and gaveworldly evidence of grace.order to make money, though they also embracedtheir simultaneously altruistic and self-interestedresponsibility to guide the affairs of the prodigiouslyexpanding city. They were shamelessboosters, but the town’s development outstrippedeven their most optimistic predictions. 7 Between1850 and 1860, Chicago’s population climbed fromunder 30,000 to almost 110,000, and it exploded tonearly 300,000 during the following decade.By the time Evans opened a private practice onClark Street, his prior experience at Rush MedicalCollege had already made him a respected memberof the small but distinguishedChicago medical community. As aprofessor of medicine he developeda new specialty, obstetricsand the diseases of women andchildren. Among his accomplishmentswas the invention of an“obstetrical extractor,” whose silkbands, he claimed, were a greatimprovement over metal forceps.Evans published his findings in theimpressive medical journal thathe edited and co-owned with other local physicians.8 He was one of the organizers in 1850 of theChicago Medical Society, which he representedthat year at the national meeting of the three-yearoldAmerican Medical Association. Evans alsoco-founded and served as physician to the femalewards of the Illinois General Hospital of the Lake.When Chicago and the nation suffered from themajor cholera outbreak of 1849, he published anarticle, which also appeared as a pamphlet, dismissingthe dominant miasmatic theory of diseasetransmission and arguing that contagion was thecrucial factor in the spread of epidemics. 9But the financial opportunities Chicago presented,not medicine, soon became the center ofEvans’s attention, leading to a major career changefrom physician and professor to full-time businessman.Even as a doctor, Evans was an investorin Chicago real estate. With the assistance of aloan from his father, he purchased a three-storybrick commercial building diagonally across thestreet from the downtown block that was andstill is the site of the Chicago City Hall and CookThe Life and Career of John Evans 13

County Building (the current structure was builtin 1911). The Evans Block, as his property wasknown, housed not only his medical practice butalso several other businesses, including some ofthe staff of the Chicago Tribune. A clear indicationof Evans’s transition from one calling to anothercame in 1852 when he traded the medical journal,of which he was now sole owner, for five acres ofChicago land. Developing his multiple holdings—which often entailed complex financing and, giventhe city’s muddy setting, extensive draining—soonconsumed virtually all of Evans’s attention. Bythe mid-1850s, he was a very affluent man and nolonger practicing medicine. An accounting set hisnet worth at over $200,000, which equals roughly5.5 million 2013 dollars. 10By then Evans also had become deeply involvedin railroads, which, along with real estate, wouldoccupy most of his energy and resources for therest of his life. The two enterprises were closelyrelated, since the building of railroads required theacquisition of land and rights of way, and accessto railroads raised the value of real estate. Evans’smost important Chicago undertaking of this kindwas the organization in 1852 of the Fort Wayne andChicago Railroad, later part of the PennsylvaniaRailroad system. A key associate was fellow OldSettler and land speculator William Ogden, who in1837 had been elected the city’s first mayor.Although the main motive behind Evans’stransition from physician to businessman was thedesire to become rich, he also devoted a significantamount of time to public service. From 1853to 1855, Evans served two terms as a Chicagoalderman. In what was hardly an uncommonpractice—Ogden was only one of many otherexamples—Evans was not hesitant about usinghis political position to his financial advantage. Helater recalled how he introduced the ordinance thatobtained the right of way for the Fort Wayne andChicago from downtown to the Indiana state linein exchange for draining the land the tracks crossedand providing free transportation for residentsin the area. 11 This was not illegal, and neither henor men like Ogden considered it corrupt, sincetheir efforts helped develop the city. In addition,Evans directed much of his effort as alderman toproviding infrastructure and public services essentialto the health and prosperity of Chicago and itspeople and to his stake in the city’s future. Amongthe vital measures Evans supported were raising thegrade (which entailed lifting most downtown buildings,including the Evans Block, and putting in fill)in order to install sewers, authorizing a capaciousand publicly owned waterworks, and constructingnew streets, alleys, and sidewalks.Alderman Evans made his greatest civiccontribution as chair of the council’s <strong>committee</strong>on public schools. When he moved to Chicago,local public education was mediocre, and if parentscould afford to do so, they educated their childrenprivately. During Evans’s tenure on the council, thecity expanded and unified its educational system,appointed a superintendent, and opened its firstpublic high school. 12 Evans advocated these changesin the belief, instilled in him by Matthew Simpson,that the future of the community depended onsuch measures. Simpson’s influence is evident ina speech Evans delivered on leaving office. Heexalted education as “the only sure ground for theimprovement of our social and political condition”and “the only guarantee of the perpetuity of ourfree institutions.” This being so, “Everything . . . thatis calculated to improve our public schools, and torender them efficient instruments in bringing aboutthat high state of public intelligence and virtue,essential to happiness, and which they are designedultimately to secure, must be of the highest interestto every good citizen.” 13Nothing fulfilled Simpson’s call to action,particularly in the field of education and theadvancement of Methodism, so much as the mostenduring undertaking of Evans’s Chicago years,Northwestern University (originally written “theNorth Western University”). On May 31, 1850, heand eight other public-spirited Methodists convenedin the downtown office of attorney GrantGoodrich. After a prayer from Reverend ZadocHall of the Indiana Street Church, they resolvedthat “the interests of Sanctified learning requirethe immediate establishment of a University in theNorth West under the patronage of the M[ethodist]E[piscopal] Church.” 14 “Immediate” turned out tobe five years, for it was not until November 5, 1855,14 Chapter Two

The minutes of the meeting at which Northwestern University was founded. It reads, “By appointment a Meeting of Friendsfavorable to the establishment of a University at Chicago under the patronage and Government of the Methodist EpiscopalChurch was convened at the office of Grant Goodrich Esqr May 31, 1850.” The list of names includes “John Evans, M.D.”(Northwestern University Archives)Old College (as it came to be known), Northwestern’s first building, was constructed in 1855 at a cost of just under $6,000,and it received the university’s first students in November of that year. Originally situated on the northwest corner of DavisStreet and Hinman Avenue, it was moved to what is now the site of Fisk Hall in 1871, where it housed a prepatory school. In1899, in order to make way for Fisk, it was moved north, to where the McCormick-Tribune Center is currently located. OldCollege served a number of different purposes between then and the mid-1920s, when it became the home of the new Schoolof Education. It was demolished in the summer of 1973 after a lightning strike set off the building’s sprinkler system, badlydamaging the structure. (Northwestern University Archives)The Life and Career of John Evans 15

This photograph, likely taken from the top of UniversityHall around 1875, offers a winter view south down HinmanAvenue. The third vertical line from the left indicates thelocation of the Evans home. The line on the left points to apier (where the limestone for University Hall was unloaded),the other lines to the homes of neighbors. The site wasabove Clark Street, just west of what is now Sheridan Road.(Northwestern University Archives)that Northwestern welcomed its first class of tenstudents—only four of whom appeared that day. 15Evans threw himself into this venture in histypical fashion, taking a lead role (often the leadrole) in drafting the university’s charter, obtainingapproval from the state legislature, and selecting thefirst president (the Reverend Clark T. Hinman, whodied unexpectedly in 1854). After the foundersdecided not to build in Chicago but instead choseas a site a farm along Lake Michigan about a dozenmiles north of the center of Chicago, Evans negotiatedthe mortgage, providing the first payment andguaranteeing the rest. The plan was to sell a portionof this property in order to fund the university, creatingat the same time an attractive settlement thatwas a center of Methodist values, including temperance.Convinced that good transportation facilitieswere a must, before completing the purchase Evansascertained that a rail line soon would connect thesite to Chicago. His fellow trustees elected himchairman of their board, and they named their newtown Evanston in his honor. He and they helpedestablish the Garrett Biblical Institute (now theGarrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary), whichalso opened in 1855.Evans was one of the first purchasers of residentialproperty in Evanston. His comfortable house—graced with a barn, fruit trees, a vegetable garden,flower beds, and gravel walks—is long gone,but it occupied much of the large piece of landat the southeast corner of the Evanston campusbordered by Sheridan Road to the east and north,Clark Street to the south, and the alley betweenSheridan Road and Hinman Avenue to the west. 16Evans moved here from Chicago in 1855, bringingwith him his second wife, Margaret Gray Evans,the sister of the wife of his fellow Northwesternfounder and trustee, Orrington Lunt, a wealthygrain broker who, like the Gray sisters, came fromBowdoinham, Maine.John and Margaret had married in 1853, threeyears after Hannah Canby Evans died of tuberculosis.Of John and Hannah’s four children, only theirsole daughter, Josephine, survived past early childhood.John and Margaret also had four children.Their daughter Margaret died of scarlet fever whenshe was five, a few months after John Evans movedto Denver but while the rest of the family was stillin Evanston. Both parents took Margaret’s deathvery hard. Their other three children—two sonsand a daughter—lived long and active lives. JohnEvans’s letters to both his wives reveal that he was a16 Chapter Two

John Evans and Margaret Patten Gray (1830–1906), hissecond wife, were married in her hometown of Bowdoinham,Maine, on August 18, 1853. Margaret’s sister Cornelia wasmarried to Evans’s close friend and fellow Northwesternfounder Orrington Lunt. Another sister married PaulCornell, an attorney and real estate developer who foundedthe town of Hyde Park, which in 1889 became part ofChicago. (Northwestern University Archives)devoted suitor and loving husband who shared hismost personal thoughts and feelings with them. 17Orrington Lunt (1815–1897).From 1875 to 1895 Lunt wasvice president of the executive<strong>committee</strong> of the Board ofTrustees and then served brieflyas president, succeeding JohnEvans. Among his gifts to theUniversity was $50,000 towardthe funding of the Lunt Library(now Lunt Hall, where theDepartment of Mathematicsis located), which opened in1894. (Northwestern UniversityArchives)Widening AmbitionsOne of Evans’s most ambitious enterprises duringhis Chicago years reflected his interests in realestate, railroads, and religion, and in importantrespects it set the pattern that defined the final fourdecades of his life. In 1857, he joined with others ina land and transportation scheme that involved thecreation of a town called Oreapolis, located on theeastern border of the Nebraska Territory about fifteenmiles south of Omaha, where the Platte Riverflows into the Missouri. Oreapolis was one of theera’s countless would-be railroad centers that wereconceived by speculators hoping to cash in on thelure of the West to settlers, prospectors, and otherbusinessmen and investors. Oreapolis was intendedto be different from most of the rest, however.Like Evanston, it would be a center of learning andpiety, an expression of the Methodist mission tospread the “good news” of Christianity and to makesolitary places “glad.” 18 From the outset, the planentailed a university, a Methodist seminary, and aBible institute under the direction of the ReverendJohn Dempster, who was serving at the time as thefirst president of Garrett.When gold was discovered in Colorado thefollowing year, the venture appeared to be a surething. John wrote to Margaret from the fledglingboom town, where he had gone for an extendedstay in order to direct operations first-hand, “I shallmake a road that will be a great thoroughfare tothe gold regions” and the Pacific Coast, “and whenthe road is once opened it will make Oreapolis thegreat starting point for the over land routes to thosepoints.” The settlement, he predicted, “will make agreat city and there can be no mistake.” 19The Life and Career of John Evans 17

By the fall, however, Evans realized that evenhis prodigious energy and gifts as a businessmancould not turn Oreapolis into a success. Thelooming Civil War delayed the construction ofthe transcontinental railroad, and many possibleinvestors doubted that the tracks would passthrough Oreapolis (when the Union Pacific wasconstructed in the late 1860s, its route crossed theMissouri River at Omaha). Capital dried up, andthe boom collapsed. Early in 1860, Evans gave theventure one more try when he attempted to interestthe members of the Chicago Board of Trade bypointing out to them that Oreapolis was in easyreach of “a gold field of unsurpassed richness andextent, a fair portion of the immense trade of whichmay be secured to Chicago if proper exertions aremade for the purpose at an earlyday.” 20 This appeal failed, andEvans withdrew from the project,though not from his belief thatthe West was ripe for moneymakingand Methodism.Another and potentiallymuch better opportunity to acton this belief soon appeared, inan indirect and unanticipatedway. Evans was one of the many Whigs who, as theparty imploded in the 1850s over the issue of slavery,gravitated toward the Republican Party and thecandidacy of Abraham Lincoln, whom Evans knew,if (by his own description) “not very intimately.”He recalled that they subsequently became “wellacquainted” when Lincoln was devising his campaignstrategy. 21 Like Lincoln at this point, Evansobjected strongly to slavery as wrong in principleand cruel in practice, and he opposed admittingadditional slave states to the Union. He believedCongress could and should ban slavery in the territoriesand the District of Columbia. But he did notyet advocate immediate abolition in the slaveholdingstates. 22 Although he did not participate in thenational convention in Chicago that nominated thefuture president, Evans was a delegate to the Illinoisstate Republican convention in 1860 that endorsedLincoln’s favorite-son candidacy.After the election, when the victor was distributingappointments to supporters, Evans’s friendsJust why the forty-eight-year-oldEvans, so comfortably settled inEvanston and Chicago, was eager totake this new and faraway job is amatter of speculation, but the likelyreasons are not elusive.from his Oreapolis days tried to convince Lincolnto name him territorial governor of Nebraska.Bishop Simpson, who at Evans’s urging had recentlymoved to Evanston and would live there until 1863,also supported him for this post, but he did notget the job. Soon Lincoln instead offered Evans thegovernorship of the Washington Territory, whichhe turned down as too remote.With backing from Simpson and severalpowerful politicians, Evans successfully lobbiedfor the same position in a nearer venue: Colorado,which had been made a territory in 1861. Its firstgovernor, William Gilpin, had lost his position forauthorizing payments to raise a military regimentwithout first getting approval from Secretary ofWar Edwin Stanton. Evans took the oath of officein Washington on April 11,1862. At the same time, Evanswas named Colorado’s ex officioSuperintendent of Indian Affairs.Soon after returning home toEvanston, he set off on the twoweekjourney, crossing the plainsby stagecoach and arriving inDenver on May 16, where SamuelElbert, an ally from his time inNebraska, joined him as territorial secretary. Elbertsoon began to court Evans’s daughter Josephine.They were married in 1865 on the lawn of John andMargaret’s Evanston home, with Bishop Simpsonpresiding. Josephine’s health was never strong, andshe died of tuberculosis in 1868, a few months afterthe death of her infant son. In 1873–74, Elbertwould serve as sixth governor of the territory, andfrom 1877 to 1893 on the Supreme Court of thestate of Colorado, the last four years as chief justice.Just why the forty-eight-year-old Evans, socomfortably settled in Evanston and Chicago, waseager to take this new and faraway job is a matter ofspeculation, but the likely reasons are not elusive.Colorado’s future was full of opportunities, some ofthem literally golden, and Evans apparently had losta good deal of money in Oreapolis. 23 The governor’soffice would put a shrewd real estate investorand railroad builder like Evans in a particularlyadvantageous position. Pursuing his own interestswas hardly likely to conflict with the Lincoln18 Chapter Two

Facsimile of John Evans’s certificate of appointment as Governor of the Territory of Colorado. The certificate is signed byPresident Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward. While it is dated March 6, 1862, Evans was not swornin until April 11, and he did not arrive in Denver until May 16. Although the certificate specifies a four-year term, in July 1865Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, speaking through Seward, asked for Evans’s resignation. (Colorado State Archives)administration’s agenda of extracting the miningriches of the West and transforming the plains intoranches, farms, and settlements. He also knew thatRepublicans looked forward to Colorado becominga state, since it almost certainly would send twomore party loyalists to the Senate.Evans had every reason to believe that he wouldbe one of those senators, which would furnish himan even grander stage from which to advance theinterests of his country, his church, his family, andhimself. As Edgar Carlisle McMechen writes, “Itmay be that [Evans] did not part from the Landof Accomplishment [i.e., Chicago] without deepregret—indeed, he retained his Evanston homefor many years afterward—but it is safe to say that,when he faced the Land of Promise [i.e., Colorado],high emprises filled his mind to the exclusion of allelse.” 24More specifically, Evans needed no one toexplain to him the financial opportunities presentedby the projected transcontinental railroad.The same year he was appointed governor, Evanswas selected by Congress to be one of the 158commissioners of the newly incorporated UnionPacific, which was the key piece in the plan to spanthe continent. The territory (and then the state)The Life and Career of John Evans 19

would gain greatly if Evans could convince othersto run the tracks through Colorado, which he triedto do during trips east during his governorship.To accomplish all this would be a challenge,but of the sort that had consistently excited JohnEvans and elicited his best efforts. The new governorseemed to have his high hopes affirmedwhen, shortly after he took office, Overland StageCompany ownerBenjamin HolladayColorado’s politics were at least ashosted him on anunruly as Chicago’s, and the local overnight trip intosituation was volatile. Evans soonthe mountainswest of Denver.learned that a particular decision or “There,” Evans toldpolicy could simultaneously make his wife, “we sawthe mills that arefriends and enemies, both of whomtaking out so muchmight have significant followings gold.” Although thewithin the territory and influence Civil War might beslowing migration atbeyond it.the moment, “Still ina few years the vastbasis of untold wealth in these Rocky Mountainswill be known and the rush will again be hither.” 25A few days earlier, on his first Sunday in Denver,Evans had his initial encounter with the aspect ofhis duties that ultimately cost him the governorship.In the heart of Denver he witnessed what he possiblymisidentified as a war dance of Sioux, Arapaho,and Cheyenne Indians. Twenty-seven years later, herecalled that the ceremony “impressed me with thesavagery of the Indians.” Citing his Quaker heritage,he also remembered his unsuccessful (and arguablynaïve) attempt to lecture historically antagonistictribes to make peace with each other. 26Evans was too perceptive not to realize in fairlyshort order how important his relationship with theIndians of Colorado would be, too intelligent not tolearn a good deal on the job, and too hard-workingand determined not to have some limited successesas superintendent, despite the failures discussedelsewhere in this <strong>report</strong>. Meanwhile, as governor,he needed to focus on his multiple other responsibilities.His central duty was to establish a stablelegal and social order among a population consistingof disparate newcomers and the indigenousinhabitants. The non-Native people of the territorywere independent-minded individualists andanything but a unified group. Some were Hispanicswho lived mainly in the southern parts of the territoryand faced suspicion and prejudice from AngloColoradans. (One of Evans’s accomplishments wasto have the territory’s laws translated into Spanish.)Colorado’s politics were at least as unruly asChicago’s, and the local situation was volatile. Evanssoon learned that a particular decision or policycould simultaneously make friends and enemies,both of whom might have significant followingswithin the territory and influence beyond it.Tensions arose between the governor and the territoriallegislature over several issues, and, if Evanscould generally rely on the bombastic backingof William Byers and his Rocky Mountain News,he could also count on abusive and even viciouscriticism from other voices in the local press. For allthe anticipation of wealth and prosperity from themines and the land, 1860s Colorado was heavilydependent on the East for basic supplies and provisions.The prices of these were always steep, andthey could become unavailable altogether if Indiansinterrupted the wagons and stages. At this point,railroad trains reached no farther than easternNebraska and Kansas. A terrible fire that struckDenver in April of 1863 and disastrous floodingthat devastated the town in May of 1864 posedadditional serious challenges.In this context, Evans made impressive progress.He initiated infrastructure projects, appointedjudges, planned a penitentiary and a poorhouse,commissioned militia officers, set bounties onfugitives, issued pardons, and generally tried tofashion and maintain a functioning society almostfrom scratch. In his first address to the legislature,delivered a month after he arrived, Evans noted theneed to consolidate counties, improve election andtax collection procedures, and amend militia regulations,not to mention institute a code of laws. Heremained true to his interest in education, which,as in Chicago, he called “a matter of the greatestimportance to the future welfare of society.”Drawing on his business experience, Evans made apriority of removing impediments to the economicdevelopment of the state. This meant, among other20 Chapter Two

things, preventing corporate monopolies, grantingmore rights to those who worked the territory’smines than to absentee owners who did not, and,of course, routing the transcontinental railroadthrough Colorado. 27 All of thesepublicly valuable measures werealso important to Evans’s hopesof expanding his own fortunesthrough investments, whichincluded mining, and to hisMethodist faith, which saw economicexpansion and strengtheningthe church as linked.Evans spent a significantamount of time, especially in1864, promoting statehood,which he believed would greatlyimprove the chances of bringingthe Union Pacific throughColorado and of obtaining betterfederal military protectionfor settlers. Besides, he couldnot become a senator unlessand until the territory became astate. The proposal incited outspokenand powerful oppositionfrom residents who thought that Colorado had toofew people and was not ready for self-government.Some opponents feared that statehood would shiftmany costs from the federal government to thelocal population, make the territory more ratherthan less vulnerable to Indians, and subject themale inhabitants to conscription into the UnionArmy. In addition, the Hispanic population of thestate was wary of turning over authority to localleaders who were prejudiced against it. In the faceof much ad hominem criticism, Evans removedhimself from consideration for the U. S. Senateshortly before the statehood election scheduled forSeptember 13, 1864. The voters nonetheless choseby a large margin to remain a territory. 28Following his resignation after the Sand CreekMassacre, Evans continued to advocate statehood,and almost exactly a year after the 1864 electiona narrow majority of the electorate agreed. Theterritorial legislature named Evans one of its twosenators, pending Congressional and presidentialapproval of admission to the Union. Althoughnumerous senators and congressmen were againstColorado statehood, Congress did endorse it. 29 ButPresident Andrew Johnson, locked in battle withthe Radical Republicans, supposedlytold Evans and fellowSenator-designate Jerome B.Chaffee that he would sign thestatehood bill only if they wouldagree to back him in the future,and they refused. In any event,Johnson vetoed the measure,and subsequent attempts tooverride the veto or to obtainhis signature on a second statehoodbill both failed. 30 Coloradodid not become a state until1876.Colorado MagnateWhile he remained an influentialpresence in DenverJohn Evans, ca. 1870. (Northwestern and Colorado politics, EvansUniversity Archives)abandoned the idea of holdingelective public office after1866 and seems not to haveregretted doing so. 31 He also appears never tohave considered leaving the state, even thoughhis wife had difficulty feeling at home there andspent extended periods abroad in the 1870s. Hehad no need to depart because of Sand Creek,which was more likely to win praise than blamefrom most non-Native Coloradans. He continuedhis active involvement in the civic and religiouslife of Denver, donating to multiple institutionsand repeatedly making good on his pledge to givefunds to new religious congregations in Coloradoregardless of denomination. Meanwhile, he wasa mainstay of his own church, active in its affairsand generous with his contributions. Here, too, hesought and achieved high office. He favored theinclusion of non-clergy on the governing GeneralConference of the Methodist Church, and in 1872,the first year his view prevailed, he won election tothis body. He would be reelected every four yearsup to 1892. Following the pattern established atNorthwestern and attempted in Oreapolis, he wasThe Life and Career of John Evans 21

The depot of the Denver Pacific Railway. Evans was themain figure in the construction of this line after the transcontinentalrailroad route bypassed Denver and Colorado. TheDenver Pacific linked Denver to Cheyenne, in the WyomingTerritory, which was on the transcontinental route. (DenverPublic Library)the leading founder of the Colorado Seminary in1864, and after it faltered he supported its reestablishmentin 1880 as the University of Denver. Evansbecame its long-time board president and a majordonor.The former governor concentrated above allon his business dealings. At first his attempts tomake Denver a railroad hub seemed fruitless, sincehe could not convince the Union Pacific to sendthe transcontinental railroad through the city. Indefiance of obvious fact, he contended that the highand rugged mountains to Denver’s west were nota serious impediment. He commissioned overlyoptimistic surveys of a route through BerthoudPass, but in 1866 the Union Pacific decided to layits tracks along a less challenging path throughCheyenne, a hundred miles to the north of Denverin Wyoming Territory. 32Perceiving this decision as a dire threat to hisown and Colorado’s financial future, Evans becamea railroad man on a far more ambitious scale thanhe had been in Chicago. Between the mid-1860sand the early 1890s, he threw himself serially intoseveral major railway projects. These includedan economic lifeline from Denver to Cheyenneand the Union Pacific, a link between the cityand Colorado’s mining regions, and a route to theGulf of Mexico. The last of these would lower thedistance by train between Colorado and the closestport serving vessels crossing the Atlantic and at thesame time reduce the city’s dependence on EastCoast middlemen. Evans also developed a streetcarsystem for Denver.It is impossible to overstate the complexity ofthe economic, political, and legal maneuvers (notto mention corporate name changes) Evans andhis shifting cast of partners devised along the wayor the ferocity of his fights with opposing investorsand lines. 33 Railroading and other investmentsmade Evans an exceptionally wealthy man, but alsoat times cash poor. 34 At the end of his life, the combinationof the Panic of 1893 and his failing acuityhad thrown his finances into disarray. 35When John Evans died on July 3, 1897, hewas a much-admired figure. Not only streets andtowns but also one of the highest peaks in the frontrange of the Rockies, visible from Denver, hadbeen named after him. As he lay on his deathbed,local officials detoured pedestrians and streetcarsfrom the vicinity of his home at Fourteenth andArapahoe Streets so as not to disturb his finalhours. Governor Alva Adams ordered that Evans’sbody lie in state in the capitol for public viewing,and by many estimates his was the largest funeralin Colorado history. Spectators lined the streetson a blazing hot day as the casket proceeded toRiverside Cemetery, where he was buried accordingto Masonic ritual.22 Chapter Two

University of Denver Chancellor WilliamFraser McDowell observed in his eulogy thatEvans “had in him the stuff from which pioneers,world-builders, empire makers are made.”McDowell praised the former governor as “abeginner of things, an explorer, a John the Baptistmaking the rough places smooth.” No individual,he reminded his fellow mourners, could take a trainin or out of Denver “but owes a debt of gratitudeto the man who made the railroads of the statepossible,” no person in search of solace and mercyin any of the city’s churches “but is a debtor to JohnEvans,” and no child in the state could attend school“without an acknowledgment to the great brain andgreat heart of the man who made these institutionsstrong through his interests and his liberality.” 36Most obituaries from near or far affirmed thisview. Few made any reference to why Evans leftthe governorship, and if they did, virtually nonecited the Sand Creek Massacre as the reason. 37 Justbefore Evans died, the Rocky Mountain News madea rare reference to the massacre, dismissing theblame the governor had received thirty-two yearsearlier as based on “malicious misrepresentations.”Evans had retired from office, the News insisted,“enjoying the fullest confidence of the people of theterritory.” 38A Man of His TimeYet another respect in which John Evans was arepresentative man was the extent to which hesincerely believed in the pieties of his age. Forexample, he told the 1850 graduating class of RushMedical College that because their professionprovided them a prominent place in society, theymust take care that their “high mission of reliefto the sick be accompanied by the refining andpurifying influences of the Christian virtues.” Thiswould help cure their patients’ “moral infirmities”as well as their physical ailments. To do so wouldbe to “emulate your Great Exemplar in going aboutdoing good.” 39 Evans similarly championed thevalue of hard work. Troubled by his fifteen-yearoldson William’s lackadaisical attitude toward hisstudies, Evans admonished him, “You are just at theage when your habits are of the utmost importanceto your future character.” The effort expended nowon correcting bad ones “will lead you into a life ofindustry & usefulness.” To do otherwise was to riskan existence “of aimless inattention if not worse.” 40Evans apparently had few doubts that, for a personof sound faith and character like himself, doingwell and doing good were entwined. 41 He viewedthe accumulation of wealth as placing one under asacred obligation to devote it to constructive socialuse. In the same 1855 letter in which he informedhis wife Margaret that his holdings put his fortuneat over $200,000, he immediately reflected on whatthis meant. “Oh!” he told her, “what a responsibilityto take care of and use aright such an amount ofproperty.—Oh that the Lord may enable me to useit for his glory & for the good of those under mycare and protection. But life is uncertain and I musttry and make some disposition of it so that it will bedevoted to good whether I live or die.” 42But did he increasingly put doing well ahead ofdoing good, particularly by the time he had becomea railroad man in Colorado? Some have thoughtso. After interviewing Evans and Samuel Elbert in1884 as part of his monumental endeavor to documentthe American West, historian Hubert HoweBancroft waspishly noted to himself, “AboutEx-gov. Evans, and his son-in-law Judge Elbertthere is much humbug. They are cold bloodedmercenary men, ready to praise themselves & eachother profusely but who have in reality but littlepatriotism.” BancroftEvans apparently had fewdoubts that, for a person ofsound faith and character likehimself, doing well and doinggood were entwined.added, “I never met arailroad man who wasnot the quintessenceof meanness in moreparticulars than one.” 43And even Evans’s sympatheticbiographerHarry E. Kelsey Jr.writes, “All of his railroadenterprises were intended to help himself,Denver, and Colorado, in about that order.” 44Such remarks may not do the man justice,especially when one considers his career as a whole,including his vast service to the Methodist Church,to Northwestern University and the Universityof Denver, and to people in all the places that helived, not to mention the considerable amount ofThe Life and Career of John Evans 23

wealth he gave away. His defenders might pointout that, if Evans was mercenary, he did indeedhelp Denver and Colorado, and not just himself,which distinguished him from several far greedierand less honest railroad developers and leaders ofother industries of the Gilded Age. If the certaintieshe cherished included belief in his own rectitude,his record of positive achievements justifies hishigh self-regard. But there is some truth behindBancroft’s comment. Convinced of the importanceof doing right, John Evans seems to have maintainedthe self-satisfied view that something wasright because he had done it.John Evans and Northwestern’s FinancesAs part of John Evans’s efforts to lay strong foundationsfor Chicago’s public school system and a newuniversity for the former Northwest Territory, hesought to endow them with income from specificblocks of land. During his two terms as a Chicagoalderman and head of the Common CouncilSchool Committee in 1853–55,he reserved rental and leasingproceeds from certain lots ownedby the city to pay for public education.This practice offered, hebelieved, so steady a likely revenuestream that he devoted his valedictoryremarks to the mayor andhis fellow aldermen to expressinghis “hope therefore that neithera desire of officers to obtain a into existence.percentage on sales, nor a wish ofothers to obtain good bargains nor yet a misguidedshort sighted, though ever so honest policy, willinduce those having control of the estates belongingto our school fund to sell any of them, at leastfor a long term of years yet to come.” 45 This practiceof retaining real estate as principal and using itsyields as operating income became the hallmarkof Evans’s financial strategy for the North WesternUniversity that he helped bring into existence at thesame time. His first gifts to the institution consistedof land, and he remained dedicated to this form offinancing ever after.Evans “subscribed” (i.e., pledged) $5,000in 1851 to help launch the new university, andThis practice of retaining realestate as principal and using itsyields as operating income becamethe hallmark of Evans’s financialstrategy for the North WesternUniversity that he helped bringthen made good on his promise in two stages.Between 1852 and 1855, he and his brother-inlawOrrington Lunt each contributed $4,000, paidin installments, toward the purchase of sixteenlots of land at the corner of LaSalle and JacksonStreets in Chicago, then at the southern edge of theexpanding downtown, with the income reserved forthe use of the recently chartered institution. ThatEvans’s donation did not consist exclusively or perhapseven primarily of his own funds is clear fromhis later recollection that “my friends came in liberallyand we raised the money.” 46 And, in October1853, Evans made a $1,000 down payment on thepurchase of 379 acres of the Foster Farm, alongLake Michigan in the future town of Evanston.Although he also assumed responsibility for theremaining $24,000 of the purchase price, due overten years, Evans (as he anticipated) did not have tomake further payments on either the principal orthe 6% annual interest on the unpaid balance. Thetrustees retired the mortgage out of the proceedsof selling or leasing parts of theacquired land to people whoplanned to build a home or opena business in the town. 47Evans made only minoradditional donations to theUniversity in its first decade,although he did occasionally paycontractors out of his own pocketand obtain reimbursement fromthe treasurer. He was one of thefirst buyers of land in Evanston,however, putting $240 down in July 1854 forLots 1 and 10–16 in Block 10, with another $960due in installments by January 1, 1862, and in 1855he purchased for $200 two “perpetual” scholarshipsthat covered future tuition at the university formembers of his family and their heirs. 48The two land deals of the early 1850s were byfar Evans’s most important gifts to Northwestern.Although they came at relatively little cost to him(perhaps $3,000 of his own money), they yieldedthe majority of the university’s annual incomeduring the first forty-nine years of its existence,outstripping tuition revenue, the sale of scholarships,and proceeds from other endowments until24 Chapter Two

The first pages of the “Perpetual Scholarship” subscriptionbook. One of the ways the new North Western Universityraised funds was by selling these scholarships for $100 each.The scholarship covered the tuition of a son and grandson ofthe purchaser, and it could be passed on to future generations.As this indicates, Northwestern’s first president, theReverend Clark Hinman (1819–1854), purchased the firsttwo scholarships, followed by John Evans and OrringtonLunt, who also each purchased two. Hinman died atthirty-five in 1854, the year before the University beganoffering classes. Evans and his family used only one of theperpetual scholarships and did so only one time, to educatethe elder of his two sons, William Gray Evans, Class of 1877.The tuition was ten dollars per term in William’s first year,fifteen dollars per term when he was a senior. (NorthwesternUniversity Archives)1900. Thereafter, the relative importance of thetwo pieces of real estate (and of income from landin general) declined, but they continued to give offnoteworthy returns. 49The LaSalle-Jackson property was especiallylucrative. It became the site of a portion of theluxurious Grand Pacific Hotel and resulted in totallease income of about $417,000, some 27% of theUniversity’s revenues, from 1867 to 1895. 50 By thelatter year, when the hotel failed, Northwesternowned the part of the building on its land as well,which the University opted to replace with a newstructure. Leased in 1897 to the Illinois Trust SafetyDeposit Company for 99 years, that edifice stooduntil the 1920s, when a new building spanningthe entire original Grand Pacific site became thehome of Continental Illinois Bank, the successor toIllinois Trust. The lease continued, and it netted theUniversity almost exactly $8 million over the life ofthe contract. Early in the 1980s, Bank of America,the successor to Continental, paid $20 milliontoward buying Northwestern’s part of the property,and then completed the purchase on April 30,1996, at the expiration of the original lease, with anadditional payment of $22,740,071.64. 51 In short,The Life and Career of John Evans 25

a plot of land acquired by Evans and Lunt’s successin drumming up $8,000 in the 1850s generatedunadjusted net income for Northwestern over thenext 130 years of almost $51 million.The sale or rental of land, most of which hadcomposed the Foster Farm in Evanston, accountedfor another approximately 24% of Northwestern’stotal income in the period 1867–95, about$318,000 of slightly more than $1.5 milliondollars. 52 But, although the town grew quickly, sodid the fledgling institution’s expenses. As early as1866, Evans feared that these twin trends wouldtempt the trustees into the sort of “short sighted”property sales against which he had warnedChicago’s mayor and aldermen. He thereforedecided to combine a new gift that would improvethe school’s balance sheets with stipulations thatwould restrict the trustees’ freedom to sell land inthe future.In November 1866, he agreed to donate severallots of land that he had long owned on MaxwellThis copy of the 1854 plan of Evanston indicates how the former Foster Farmwas divided into lots to be sold or rented, with the proceeds funding “the NorthWestern University,” whose “grounds” are on the upper right, along Lake Michigan.(Northwestern University Archives)Street in Chicago, with the provisos that (a) theycould be leased, rented, and improved, but notsold, and (b) the income would be used, first in1867–68, to satisfy Evans’s promise to contribute$5,000 toward the construction of the collegebuilding that became known as University Hall,and thereafter, to support a chair in Moral andMental Philosophy that, in practice, provided theUniversity president’s salary ($2,500 per year in1876–88, $3,000 per year in 1886–90, and $3,500per year in the 1890s) for the next three decades. 53In return, Evans extracted the board’s promise toretain in perpetuity one-quarter of each still unsoldblock of land in Evanston for lease, rent, or lastingimprovement. 54 He maintained that holding ontosome land permanently would enable the universityto share in the rising property values that Chicago’sand Evanston’s growth were certain to bring.Evans’s attendance at the annual meeting of theBoard of Trustees in 1866 was his first appearancesince 1861, the year before he moved to Colorado.Though he remained Presidentof the Board until 1895, heattended the annual meetingonly five more times (in 1871–72,1876, and 1889–90). Most ofthe board’s decisions were made,in any case, by the executive<strong>committee</strong> of the Board’s officersplus three to seven other electedmembers, but his attendance atthis smaller group’s meetingsalso was sporadic. This is notto say that he disengaged fromthe institution; he visited it fourtimes between September 1877and March 1879, again in April1887, and for the last time inJune 1894. 55 He also stayed inclose touch with his brother-inlawand fellow board memberin Evanston, Orrington Lunt.But his day-to-day interests andpriorities were largely elsewhereafter he went to Colorado.Testimonies to this are the infrequencyof his overt interventions26 Chapter Two

The deed for theFoster Farm, datedAugust 11, 1853.John Evans made thefirst $1,000 paymenton the $25,000purchase price andpledged the remainder.(NorthwesternUniversity Archives)The Life and Career of John Evans 27

These pages from the subscription book forwhat became University Hall list the first oftwo pledges made by John Evans, both of whichhe redeemed in land. The first pledge was for$2,000, the second for $3,000. Note the pledgeby Evans’s brother-in-law and Northwesternco-founder Orrington Lunt, also paid off inland. (Northwestern University Archives)This drawing of the “Proposed Building” isin the subscription book used to record thepledges (and then payments) that fundedwhat came to be known as University Hall,completed in 1869 at an estimated costof $125,000. For almost two decades thisstructure was the main campus building.It housed the University’s library, chapel,classrooms, dorm rooms, meeting rooms, anda natural history museum. (NorthwesternUniversity Archives)28 Chapter Two

in University affairs, as recorded in the records ofthe Board of Trustees, and of his donations.Northwestern’s assets grew substantially inthe years after John Evans went west. Estimatedat $704,200 in 1868, they reached $3,579,700 in1894, at the beginning of his final year as Chair ofthe Board of Trustees. But the institution operatedalmost continuously in the red. During Evans’s lasttwenty-seven years as chair, Northwestern had anoperating surplus only five times, in 1876–77 and1890–94. By 1874–75, debt service consumed fullyone-quarter of annual expenditures and accountedfor nearly all the annual deficit. Despite drasticreductions of outlays for instruction from $35,000in that year to only $16,200 in 1879–80, the interestpaid on the incurred debt actually rose slightly,and its share of the reduced overall expendituresreached almost 40%. 56 The University faced anexistential crisis, and the challenge that this posedto Evans’s financial strategy for the institutionmotivated him to take once more an active, albeitepisodic, role in the Board of Trustees’ decisions.The trigger for his renewed involvement was adiscussion in the executive <strong>committee</strong> in 1875 ofabandoning Evans’s policy of holding one-quarterof each university-owned block in Evanston forrental income. Trustee and Land Agent PhiloJudson, among others, argued that the Universitywould do better to sell those quarters of lesssought-afterblocks, to lease only those that couldreturn at least 6% of their value annually, to investsome of the proceeds in safe securities, and to usethe rest to retire the debt rapidly. In a letter writtenon the eve of a trip to Europe, Evans vigorously protested.He argued that the proposal was “founded intemporary expediency” and reiterated his view thatif the trustees “set aside this rule now and sell ourproperty to relieve a temporary emergency, the citywill grow to the same proportions, but the wealththat results from its growth, will belong to individualsand not to the University.” Rather than let goof the reserved land to obtain needed cash, Evanssuggested, the institution should reduce expensesand raise tuition and fees sufficiently to balanceBird’s-eye view of the Northwestern University Evanston campus, looking south, around 1874. University Hall, constructedfive years earlier, is in the center, and to its left is Northwestern’s first building, Old College. Just visible on the far right in thedistance is the new Women’s College, now the Music Administration Building. (Northwestern University Archives)The Life and Career of John Evans 29

This drawing offers a visual as well as verbal descriptionof the dock property, valued at $75,000, that John Evansdeeded to the University as part of the intricate series ofland exchanges that lay behind the funding of the chairshe donated in Moral and Intellectual Philosophy and inLatin. Maps illustrating Northwestern land acquisition anddisposition were kept in a series of land books, as opposedto the records and minutes of the Board of Trustees, whichgenerally include narrative descriptions of property andformal legal descriptions of land. (Northwestern UniversityArchives, Office of the University Attorney, Real EstateRecords)the annual budget, and then gradually sell enoughunreserved property to erase the burdensome debt.He thus insisted on adherence to the conditions ofhis Maxwell Street land donation of 1866, and heprevailed. 57Evans’s austerity course failed, however. As thefigures above make clear, the University’s indebtednessbecame more rather than less of a burdenby the early 1880s. So he made a new attempt tocouple his generosity with institutional discipline.When the trustees appealed to him in 1881 to helplaunch a drive to retire obligations that now cameto almost $200,000 (about 4.55 million in 2013dollars), Evans pledged $25,000 in each of twosuccessive years, provided that the Board couldfind donors of another $75,000 in each. Up to apoint, the plan succeeded, largely thanks to thegenerosity of William Deering, who contributed$75,000 during the two-year effort. Evans deliveredthe first $25,000 of his pledge on July 18, 1883.But he had attached two somewhat contradictoryconditions to his promises: (a) that his gifts werenot be used to retire debt, but rather to increasethe endowment of the chair in philosophy that hehad created and to establish a new chair in Latin,and (b) that the University would pay off its totalindebtedness within two years and never again letthat sum exceed $10,000. Partly because of (a), thetrustees could not satisfy (b). As a result, Evans letNorthwestern hold but not use the $25,000 he hadgiven, and he withheld fulfillment of the pledge tocontribute a second equivalent sum. 58This impasse lasted five years, until September1888, when Evans and the University began acomplicated set of land deals over the followingtwelve months. First, Evans released Northwesternfrom the no-sale provision regarding the MaxwellStreet lots that he had donated in 1866 and fromthe no-debt provision of his donation of 1883.He thus permitted the lots’ sale to the Chicago,Burlington and Quincy Rail Road. Just under halfof the proceeds ($25,000 of $55,000) were thenadded to the equivalent sum he had given in 1883.This $50,000 constituted the new endowment forthe pre-existing but now renamed chair in Moraland Intellectual (rather than Mental) Philosophy.Second, Evans gave the University a dock propertyvalued at $75,000 on the east bank of the SouthBranch of the Chicago River, just west of ArcherAvenue in the Bridgeport neighborhood. In return,Northwestern paid the mortgage on the propertyand a few miscellaneous bills out of the otherproceeds on the Maxwell Street sale and becamefree to realize the remaining $50,000 in value at30 Chapter Two