JOURNALISTS' SECURITY IN WAR ZONES LESSONS FROM SYRIA

JOURNALISTS' SECURITY IN WAR ZONES LESSONS FROM SYRIA

JOURNALISTS' SECURITY IN WAR ZONES LESSONS FROM SYRIA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

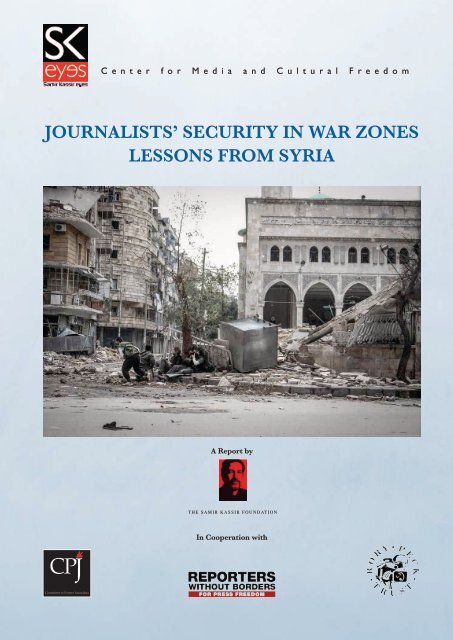

Cover photo credit:Narciso Contreras, Free Syrian Army soldiers and freelance photographers Cesare Quinto and Javier Manzano seek cover, under sniperfire in the Shaar neighbourhood of Aleppo, Syria, July 2012This project is funded by theEUROPEAN UNIONThe contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the Samir Kassir Foundation and can in no way betaken to reflect the views of the European Union.The views expressed in this report are the sole responsibility of the Samir Kassir Foundation and do notnecessarily reflect the official positions of Reporters Without Borders, the Rory Peck Trust and the Committeeto Protect Journalists.

JOURNALISTS’ <strong>SECURITY</strong> <strong>IN</strong> <strong>WAR</strong> <strong>ZONES</strong><strong>LESSONS</strong> <strong>FROM</strong> <strong>SYRIA</strong>Shane FarrellAugust 2013Center for Media and Cultural Freedom

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from SyriaAbout the AuthorShane Farrell is a security risk analyst and freelance journalist. From early 2011 he spent twoyears as a reporter based in Lebanon, covering local and regional political, security and economicdevelopments. Formerly a staff reporter at NOW Lebanon, his work has also appeared in NBC,BBC, Rolling Stone, Courrier International, among others. He studied History and PoliticalScience at Trinity College, Dublin, and Sciences Po Strasbourg, France, and completed hisMasters of Arts in the War Studies Department of King’s College London, graduating with afirst class honours in International Peace and Security Studies.4

Table of ContentsForeword...........................................................................................6Executive Summary.............................................................................7Introduction.......................................................................................8Overview and Expectations................................................................11Safety in the Field.............................................................................13Dealing with Employers.....................................................................17Dealing with Governments................................................................22Dealing with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.........................................23Conclusion......................................................................................25APPENDIX 1: Minimum Working Standards for Journalists in Conflict Zones.... 27APPENDIX 2: Recommendations to Press Freedom Organisations....................295

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from SyriaForewordWhen the Samir Kassir Foundation launched theSKeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedomin 2007, it intended to establish a resourcecentre that monitors and denounces violationsagainst journalists, media professionals, artistsand intellectuals in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan andPalestine. The mission statement of the centre alsoincluded the provision of support to journalistsfacing repression and life-threatening conditions,and building journalists’ capacity to meet thehighest professional and ethical standards.It was clear at the time that Syria would bethe most challenging operating environment.Repression, arbitrary detention and forced exileof journalists were all too common practices. Theeruption of the Syrian conflict in March 2011made the situation far more perilous. Syria hasbecome the most dangerous place on earth forlocal and international journalists alike. The risk ofabduction is higher than in any other region in theworld, and even the most conservative figures putthe death toll of journalists and citizen journalistskilled in the field at, respectively, more than 50 and100 since March 2011.Yet, foreign reporters, photojournalists andfilmmakers are still going there, braving evergreaterrisks, to shed light on one of the mosttragic humanitarian emergencies in recentmemory. However, the increased danger and themultiplication of abductions and killing have pushedmost international media outlets to refrain fromsending their staff on the ground. Most of thosewho cover the conflict in Syria today are freelancers,who may not have undergone the appropriatehostile environment training and cannot rely onthe support of established news organisations insituations where they are most at risk.In this context, it was highly important forSKeyes to organize a retreat, in a calm andpeaceful environment, for international journalistscovering Syria to reflect on the challenges theyface on a daily basis. They, better than anyone,could answer critical questions: What are thetrue security conditions on the ground? What arejournalists’ expectations from their employers?What is the best behaviour to adopt in case ofabduction? What can journalists expect from theirgovernments? What kind of assistance is availablefor freelance journalists? How can war reportersdeal with post-traumatic stress disorder?More specifically, the meeting aimed at reachingconsensus on a document outlining a series ofminimum working standards for journalists inconflict zones. SKeyes will share this documentwith other journalists covering the conflict inSyria with the hope it will serve as a startingpoint for discussions between journalists andtheir employers, defining the conditions andrequirements that should always be taken intoaccount before sending reporters into the field. Abroad endorsement of the minimum standards willcontribute to strengthening the negotiation powerof journalists and improving their protection.Finally, SKeyes would like to thank the EuropeanUnion for supporting this initiative; Reporterswithout Borders, the Committee to ProtectJournalists, the Rory Peck Trust and HumanRights Watch for their trust and active contributionto the success of the meeting; and Shane Farrell,the author of this report.Ayman MhannaExecutive DirectorSamir Kassir FoundationSKeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedom6

Executive SummaryThe face of journalism has changed radically inrecent decades. As news agencies, for the most part,have to grapple with reduced budgets, freelancersare now providing an ever larger share of newscontent. The result has been that an increasingnumber of ambitious but untrained aspiringjournalists can have content published if it meetsthe standards set by the news outlet. Yet, thesestandards are often limited to the quality of content,rather than the means by which it was acquired.Rarely, for instance, do news outlets providefreelancers with minimum standards of securitytraining or equipment. Among staff journalists thesituation is generally better, even though some ofthe largest news outlets do not provide insurancecoverage for staff reporting from conflict zones,not to mention fixers, drivers or other locals whoare so vital in the gathering of news content.The argument often raised by employers is thatthe onus is on the freelancer to prepare adequatelyfor the job at hand. Also, many journalistssimply do not raise the issues with employers inthe knowledge that there are often less securityconscious journalists who may be willing to do thejob. In war zones, however, this lack of emphasison security is a grave concern particularly sinceit is widely believed that the deaths of so manyjournalists every year in war zones could havebeen prevented had they or their colleagues beenbetter prepared.Stories of journalists entering conflict zoneswithout basic equipment or first aid training areall too familiar; so too are reports of news outletswashing their hands of responsibility regardingcommissioned freelancers. This needs to change,and it can, so long as enough voices in the industryback initiatives to implement minimum workingstandards.This was the objective of a retreat for internationaljournalists who have reported from Syria sinceconflict broke out in early 2011: to produce a setof minimum professional and safety standardsfor journalists reporting from conflict zones andtheir employers, drawing on their experiences andchallenges in the field.What follows is an outline of a series of discussionsheld over the three-day retreat among some 45journalists, photographers and filmmakers, whichled to the production of a minimum standardsdocument. Participants discussed their greatestpersonal, security and professional challengesfaced when reporting from Syria, includingexperiences with kidnappings, news blackouts,computer encryption, cultural sensitivityand post-traumatic stress disorder. Theirrecommendations are outlined in the “MinimumWorking Standards for Journalists in ConflictZones” (appendix 1) and “Recommendations toPress Freedom Organisations” (appendix 2).7

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from SyriaIntroductionBackgroundThe following is a summary of a conference held inthe Al-Bustan Hotel in Beit Mery, Lebanon, from 12-14 July 2013, which was attended by 45 journalistswho have reported from inside Syria since conflictbroke out there in March 2011. The attendees,who included both staff reporters and freelancersfrom a wide range of media, discussed difficultiesthey faced reporting from conflict areas and helpedproduce guidelines for reporters and news outletscommissioning articles, pictures and videos fromwar zones. The event was hosted by the Samir KassirFoundation’s SKeyes Center for Media and CulturalFreedom with the participation of representativesfrom the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ),Reporters without Borders (RWB), the Rory PeckTrust (RPT) and Human Rights Watch (HRW).Changing shape of journalismJournalism has changed radically – some sayirreversibly – in recent decades. The proliferationof freely available information online, a shift towardsnewsgathering through social media websiteslike Twitter (particularly for breaking news), andthe phenomenon known as ‘citizen journalism’are just some of the realities of the modern agethat are changing the face of journalism, causingnewsrooms to shrink and squeezing budgets.News outlets are adapting to this new reality indifferent ways: some outlets are charging users foronline content to generate extra income, whileothers fear doing so will merely drive customersaway. Some newspapers are simply publishingfewer pages or, like the UK-based Independent,selling cheaper but smaller versions of thepaper (1) . Most are cutting down on staff numbers (2)or, in the more drastic cases, a whole body ofjournalists (like the Chicago Sunday Times,which fired all of its full time photographersearlier this year) (3) .Across the board, news outlets are adapting tobudget cuts by increasingly relying on freelancersrather than staff reporters to provide content.This is now a burgeoning aspect of the industry.Yet, there is often a lack of standardisation oreven guidelines of best practice to ensure thehighest standards of journalism and safety aremaintained. Many outlets will accept work fromconflict zones even if the journalist does not havebasic safety training and acts in a way that mightendanger others. The most egregious exampleof this in recent times, perhaps, is an articlepublished by Vice Magazine in 2012. The title isindicative: “I went to Syria to learn how to be ajournalist and failed miserably at it while almostdying a bunch of times” (4) . Freelance journalistsby and large are serious, hard-working andprofessional. But because of the nature of thejob, which technically does not require trainingand can be done cheaply, it will always drawin ‘war tourist’ types that do a disservice to theprofession.1. The Independent’s ‘i’ newspaper was first launched in October 2010. At £0.20 (£0.30 on Saturday) it is considerably cheaperthan the main Independent paper, which retails at £1.40 for weekday editions, and £1.80 and £2.20 for the Saturday and Sundayeditions, respectively. The ‘i’ consistently sells more than the larger paper.2. See, for example, The Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism annual report ‘The State of News Media 2013’.The report, which examines US media, estimates that “newsroom cutbacks in 2012 put the industry down 30% since 2000 andbelow 40,000 full-time professional employees for the first time since 1978.” Available at http://stateofthemedia.org/2013/overview-5/.For comparative purposes, a general discussion of the shrinking newspaper industry in the US and the UK can be found here:http://www.themediabriefing.com/article/abcs-newspapers-circulation-decline.83. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/01/business/media/chicago-sun-times-lays-off-all-its-full-time-photographers.html4. Sunil Patel, ‘I went to Syria to learn how to be a journalist and failed miserably at it while almost dying a bunch of times,’ Vice.Available at http://www.vice.com/read/i-went-to-syria-to-learn-how-to-be-a-journalist

IntroductionAdditionally, there is the more common issue ofthe well-intentioned but inexperienced freelancerswith an ambition to break into journalism or toexpand their profile. These individuals are oftenprimarily motivated by having content publishedand generally are not overly concerned aboutsalary or conditions of work. In an industry facingmajor financial difficulties, it can be very temptingfor news outlets to pay low rates for contentacquired. However, this comes with a multitudeof implications, including that of driving moreexperienced journalists towards better paidprofessions and causing the freelancers to cutcorners on important elements such as preparation,training and equipment. This can, in turn, increasethe security risks for both the freelancers and thepeople they are dealing with in the war zone. Thissubject will be looked at in the section entitled“Dealing with Employers”. What should be keptin mind at this point is that the challenges facedby journalists and commissioning news editorsare vast and that the quality of news reportingwill inevitably suffer further if both groups failto adapt to the implications of a rapidly-evolvingshift in information gathering and news dispersal.Editors’ dilemmaIt should be noted that some media outlets arerefusing to accept content from freelancers or, morespecifically, freelancers who have not undergonebasic first aid or security training. The UKSunday Times famously refused to take copy fromfreelancers following the death of their veteranwar correspondent Marie Colvin, who was killedwhile reporting from Homs in February 2012.The Sunday Times reasoned that doing so wouldencourage others to take “exceptional risks.” (5)Other outlets, such as Radio France and themajor British broadsheets have adopted a similarpolicy. (6) Nevertheless, the practice is controversial,and many freelancers have expressed their criticismof such a stance saying that it should be up to themto decide whether the risks are worth taking andthat the implementation of such policies preventsimportant stories from being told.But, while the jury is still out when it comes tothe morality of accepting stories from freelancersreporting from conflict zones, there is a growingrealisation within the industry that concreteaction is needed to address such issues. In recentyears, a number of initiatives have been takento improve overall practice in an effort both tomaintain high standards while ensuring thatjournalists work responsibly and to high securitystandards. The Frontline Freelance Register, (7)for instance, is a body of freelancers whosemembers promise to adhere to a basic codeof conduct with a view to ensuring responsiblejournalism. Additionally, Frontline Club produceda white paper entitled “Newsgathering Safety andthe Welfare of Freelancers” (8) , which outlines someof the most significant issues faced by freelancers,including digital training and insurance problems.Meanwhile, press freedom organisations andjournalists’ unions are continuing their efforts toprovide journalists with advice and information,including on the most affordable insurance andsecurity training rates available to journalists.Discussion pointsThe Samir Kassir Foundation hosted this retreatfor journalists who have reported from Syria to addimpetus to these drives that aim at improving the5. See, for example, Gavin Rodgers, ‘Sunday Times tells freelancers not to submit photographs from Syria’, Press Gazette, 5 February2013. Available at http://www.pressgazette.co.uk/sunday-times-tells-freelances-not-submit-photographs-syria6. This includes the Guardian, Observer and the Independent.For more information, see http://www.pressgazette.co.uk/broadsheets-back-sunday-times-decision-decline-freelance-submissions-syria7. https://frontlinefreelance.org/8. ‘Newsgathering Safety and the Welfare of Freelancers,’ a white paper by the Frontline Club, 6 June 2013.Available at http://www.frontlineclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Safety-Report_WEB.pdf9

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from Syriaquality and safety standards of journalism. Withthis in mind, the three-day seminar took the formof a discussion between attendees, rather thanthe usual panel-focused format of conferences.Many of the journalists knew one another or werefamiliar with the work of other participants, whichcontributed greatly to the relaxed atmosphere ofthe event.The seminar was divided thematically intosessions covering the following four areas: safetyin the field; dealing with employers; dealing withgovernments; dealing with post-traumatic stressdisorder.This report will outline the main discussion pointsin each session with a view to providing an insightinto some of the biggest challenges faced byjournalists who have reported from inside Syriasince the conflict began in March 2011. In someinstances, the summary of the discussions willbe supplemented with information gleaned fromother sources available online and duly referenced.Finally, it is worth mentioning that during theclosing sessions of the retreat participants workedin smaller groups to build a set of recommendationsfor both journalists intending to work in conflictzones and their employers. The recommendationswere then combined to form the attached“Minimum Working Standards for Journalists inConflict Zones”, which will hopefully contributetowards establishing a basic set of procedures forjournalists and their employers in order to improvethe safety standards and working conditions ofstaff journalists and freelancers alike.10

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from Syriathe field, which apparently raised some eyebrowsamong Syrians. While this is a minor example,and it is unwise to jump to the conclusions, it is notinconceivable that, sometimes, foreign journalistsare not as aware of cultural sensitivities as theythink they are and that for reasons of respect,preferable working conditions and safety, thisknowledge deficit should be addressed. This couldalso be extended to language skills. Even a basicgrasp of a local language or dialect demonstratesrespect and can potentially get someone out of avery difficult spot.On a related note, it was emphasized that journalistsshould have an understanding of and empathyfor religious issues in any situation where they arelikely to be dealing with religious individuals. In thecase of Syria, and most Muslim-majority countries,knowledge of the fundamentals of Islam shouldbe heavily emphasised. In more extreme cases, adeeper understanding could save someone’s life (9) .The session ended with several journalists whorecently returned from Syria recounting theirexperiences. Participants were especially grippedwhen one journalist proceeded to recount histales from the Damascus countryside. Havingmanaged to cross into rebel-held areas, subsequentgovernment advances prevented him from escapingas exit routes were sealed off. For his own safety, hehad to remain with rebels for four months beforemanaging to escape back out of the country.The exchange of personal experiences fromthe field gave a strong indication of the fluidbattleground in Syria and how adaptablejournalists have to be when the situation changeson the ground.129. In a safety manual aimed at individuals expecting to work in a war zone, author Rosie Garthwaite details how a Médecins SansFrontières (MSF) staff member was kidnapped by Islamist militants in Chechnya and managed to save her own life using herknowledge of Islamic religious verses. As the author explains, before the MSF staff member was about to be shot, “she suddenlyremembered the call to prayer, which she had heard so many times in her childhood. The kidnappers started arguing about howit was a sign from God and decided not to shoot her. She was eventually released.” Rosie Garthwaite, How to Avoid Being Killedin a War Zone, p.34 (Bloomsbury: 2011).

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from Syria14However, many of these crossings are becomingincreasingly perilous. Bab al-Hawa and Aazazwere singled out as common crossing points thathave become highly dangerous in recent months.Much of the danger, according to participants,lies in the fact that the territory frequentlychanges hands. The border zones are oftenunder the control of radical Islamist groups orcriminal gangs, making the risk of kidnappingmuch greater than in the past. These nefariousindividuals are believed to be monitoring bordercrossings in order to pick up foreigners at a laterstage and hold them for ransom.In general, loitering around checkpoints wasconsidered potentially very dangerous, and ifvehicle swaps were necessary this ought to bedone as speedily as possible. Similarly, spendingmultiple nights at the same location was stronglydiscouraged, as it increases the likelihood ofinformation being passed to kidnappers regardingthe journalist’s location.Participants debated the risks and advantagesassociated with receiving the protection of oneof the fighting brigades (katiba). While this mightprovide some security, caution is always required.One of the most experienced journalists offeredhis advice on crossing borders and reflected moregenerally upon the changing nature of reportingin Syria:“Nowadays, you must set up your story fromoutside, pop in and out as quickly as possible - longgone are the days of doing two or three week trips.”KidnappingWhat followed was a discussion of what to do incases of kidnapping. One participant had to dealwith two cases of friends being kidnapped andstated, in no uncertain terms, that “in each casethe rumours were very damaging.” In a differentcase, rumours of a journalist’s impending releaseactually prevented his being set free. In other cases,the rumours had raised the hopes of the kidnappedjournalist’s friends and family and played havoc ontheir mental state when these rumours turned outto be false.There was no consensus on whether systematicnews blackouts – an informal agreementamong journalists, employers and families,not to publicise news of a kidnapping – is thebest approach. A majority of participants feltthat it was the best practice, but others arguedthat it depends very much on the case andthe preferences of the family. Those againstblackouts made the point that publicisingsomeone’s case can pressure their governmentinto negotiating with the captors and may helpdispel views that kidnappers might have aboutthe person they abducted being a spy. Someparticipants lamented the double standardsamong some journalists, who would adhere toa blackout of fellow journalists, but are quickto report kidnappings of non-journalists. Somejournalists made it clear to their employer inadvance whether they would want a blackoutor not. In short, it depends on the individualjournalist and the specific case at hand.The discussion moved towards means of avoidingkidnapping, particularly when it comes to commonsense use of internet communications sites.Online forums, including secret Facebook groups,were not deemed reliable places to post sensitivematerial. This is true for a range of information,from details about a kidnapped colleague toinformation regarding one’s planned entry toSyria. As the representative from a major pressfreedom organisation said:“If I can tell who’s going into Syria based solelyon their Facebook posts, imagine what the regimeor some fighting groups, with far more resources attheir disposal, can do. Frankly, it’s very foolish topost information as sensitive as that online.”

Safety in the FieldCommunications and securityParticipants then discussed the topic of preferredworking procedures once journalists were insideSyrian territory. Some journalists like to workcompletely under the radar, without fixers andrelying on local connections. However, thisseems to have been the minority view. Others,particularly those working for more establishedoutlets, encouraged colleagues to plan the tripmeticulously and to have trusted contacts in eacharea they are planning to visit before they arrive.Though, it was pointed out that in some casesit is preferable not to fix a meeting but rathershow up, conduct interviews and leave as quicklyas possible afterwards. All journalists appearedto have some form of a communication plantailored to their own preferences and the realitieson the ground through which they would touchbase with a trusted contact at regular intervalsto update them and make it known that theyare safe.The discussion transitioned seamlessly to methodsof data protection. The key advice was to installTrueCrypt, a software that enables one to easilyhide data on computers. One of the most usefulfeatures of TrueCrypt for journalists reportingfrom conflict zones is the ‘Hidden Volume’feature, which enables the user to have twodifferent passwords with each password openingup a different set of data. Typically, one set ofdata includes sensitive content while the contentof the other is innocuous. In cases where a useris coerced into revealing his/her password, thatperson can give out the password which opens updata that is inoffensive. Software like TrueCryptis difficult to trace, even for those who are awareof the technology. But, such applications are onlyeffective if users diligently follow the instructionsand remember to encrypt data routinely.Other communication devices carry their ownrisks. Caution was expressed on the need forjournalists to delete phone numbers and not tobring in their smart phones as these could endangerthe journalist’s contacts. Several participantsadmitted that they had not minimised informationon their phones. Participants also debated whetherSIM cards can be traced in the phone even whenthe device is switched off. Phone and Skype callswere deemed especially dangerous and easy tointercept. Their advice was to use VPNs or TOR (11)to encrypt conversations, a method practiced bythree quarters of the attendees. Any cellular orsatellite phone conversation should also be veryshort and it was highly advised not to make severalcalls from the same location.Reporting responsiblyOn the topic of reporting on sensitive issues,several journalists revealed that they had beenfirmly asked – by local fighters, fixers or activists– not to write about foreign fighters or Islamistradicals. But, there are ways to get around this, forinstance by securing the approval of the heads oflocal katibas and the foreign fighters themselves.There was also criticism of freelancers seeking out‘sexy’ stories about Islamist fighters and foreignjihadists, which only provides a partial view of whatis happening in Syria. There was some anecdotalevidence of Syrians becoming increasingly angryat journalists who repeatedly asked to meet withforeign fighters, even in areas where they are notknown to be present. Journalists are often overlyattracted to ‘juicier’ stories rather than towardsgiving a more balanced picture of what is takingplace. But, sometimes editors are equally at fault,as Italian journalist Francesca Borri articulatedin a well-circulated piece published this year. (12)In a moving account of difficulties she has11. VPN, or Virtual Private Network, enables users to access a network and transfer data across a public telecommunicationinfrastructure, like the Internet, as if it were a private network, such as one belonging to a private business. TOR, meanwhile,stands for The Onion Router. It is a free software that allows users to conceal their location when accessing the Internet.12. Francesca Borri, ‘Woman’s work: The twisted reality of an Italian freelancer in Syria’, Columbia Journalism Review, 1 July 2013.Available at http://www.cjr.org/feature/womans_work.php?page=all15

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from Syriaexperienced while reporting in Syria, Borrilaments the fact that:“[E]ditors back in Italy only ask us for the blood,the bang-bang. I write about the Islamists and theirnetwork of social services, the roots of their power –a piece that is definitely more complex to build thana frontline piece. I strive to explain, not just to move,to touch, and I am answered with: ‘What’s this?Six thousand words and nobody died?’”Such an editorial approach can of course givea false impression of the realities on the groundand, hence, contribute towards rising levels offear and tension. It can also affect perceptionsand policy decisions. Moreover, it has repercussionsfor other journalists and was cited as one ofthe reasons why Syrians appear to be increasinglydistrusting of journalists than they have been inthe past.With reporting, as with daily dealings withindividuals on the ground, journalists areambassadors of their profession. Malpractice byone individual – whether willingly or throughignorance – can taint the reputation of alljournalists, making newsgathering more difficultthe longer the conflict lasts.Key recommendations to journalists:• Do not loiter around checkpoints.• Do not spend multiple nights in the same location.• Respect blackout decisions in cases of kidnapping if blackout is requested by the families of abducted journalists.• Do not reveal your travel plans on online forums, including on supposedly secret online groups.• Plan your trip meticulously with trusted contacts.• Agree on a communication plan with your editor and/or a trusted third party.• Encrypt your files, communication channels and devices.• Do not make multiple calls from the same location.• Respect local cultural sensitivities.16

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from Syriafrustration highlights the need for standardisationof terms with a view to making the workingenvironment easier and more predictable forjournalists across the board.The discussion then focused on estimating costs ofreporting from conflict zones like Syria. One staffjournalist revealed what appears to be the highlyvariable costs of reporting from a conflict zoneas between $100-200 a day for a fixer/translator,$100 for a driver, and $50 for accommodation.Freelancers, meanwhile, tended to pay fixersand drivers much less, and rely on local peopleto give them a bed or floor space for the night.Arab culture is famously generous and hospitalityis highly valued. Hence, any insistence to payfor bed and board can be insulting to one’s host(which is another reason why understanding localsensibilities is so important).But, what is highly undesirable are reports ofjournalists underpaying their support team, suchas the example cited of a fixer who complainedabout an Italian freelancer paying him just €40for a day’s work on the frontlines. Then again,journalists like Francesca Borri reported earningjust €30 more than that for a piece filed from Syriafor Italian news outlets, which explains – but doesnot excuse – underpaying fixers; this behaviourmay also contribute to tarnishing the name ofjournalists.This session continued with the consensus thatsalaries must be improved and after articulatingmany of the challenges with implementing this,participants agreed that what was required wasa collective effort from journalists – possiblythrough journalists’ unions – to standardise payrates or at least make them more transparent.Several participants, however, expressed doubtsabout the feasibility of such a process. Someinitiatives have been made in this regard already.The National Union of Journalists in the UK,for instance, has a Freelance Fee Guide (14)which provides freelancers with an idea of the salarythey should expect to receive for various types offreelance content for different media outlets. Therehave been some attempts to increase transparencyacross the board with initiatives like “Who PaysWriters” and “Who Pays Photographers” (15) ,websites that compare different pay ratesinternationally, but none have been successful.Participants identified this as a potential area inwhich organisations defending journalists’ rightscould help by plugging this information gap andcreating a table with different pay rates amongmedia outlets at an international level.Insurance“Insurance is notoriously expensive. It is probablyfair to say that many freelancers are not currentlytraipsing around the hot spots of the world withoutinsurance, because they want to or because they areignorant to the need for insurance – most simplycannot afford it”.The above statement, written by freelancers ArisRoussinos, Ayman Oghanna and Emma Bealsin a paper produced by the Frontline Club (16) ,perhaps best reflects the sentiment amongfreelancers at the conference. In general, as itstands now employers will pay insurance for staffmembers but not freelancers. Freelancers andmany staffers felt that this should change and thatemployers ought to cover insurance, or at leastcontribute significantly towards it.It was also felt that journalists could “get smarterabout insurance.” Many simply do not pay for it,and some of the ones who do neglect to read thefine print. One particularly egregious example14. See http://www.londonfreelance.org/feesguide/index.php?language=en&country=UK§ion=Welcome1815. See http://whopays.tumblr.com/ and http://whopaysphotogs.tumblr.com/16. ‘Newsgathering Safety and the Welfare of Freelancers,’ a white paper by the Frontline Club, 6 June 2013. Available athttp://www.frontlineclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Safety-Report_WEB.pdf

Dealing with Employersof an insurance company not covering funeralcosts was highlighted during the conference as awarning to others. Olivier Voisin was a Frenchphotographer who reported from Syria beforegetting hit by a shrapnel and brought into Turkey,where he later died from his injuries. Voisin’sfamily had to pay for the funeral expenses.The provisions of insurance packages vary greatly,however, depending on the nature of the insuranceand the conflict. According to a June report by theFrontline Club, “A freelancer recently back fromSyria revealed that her basic insurance package fora two-week trip came to ₤280. Others, however,not satisfied with a basic package, can spend upto ₤1,000 for the same duration and location.Freelancers, who make multiple trips a year, caneasily spend thousands of pounds in insurance.”By comparison, it can be anywhere from $500 aweek in Afghanistan to $600 a month in Libya,according to 2011 figures. The consensus amongjournalists is that Reporters without Bordersoffers the most cost-effective packages, with an‘essential plan’ costing €2.71 a day for assistancecoverage in medical emergencies, with an extrapremium of €11 charged for high-risk countries. (17)Since RWB has offered this insurance coverage,over 400 people have purchased it. However,alternatives do exist, and the provision to bothjournalists and employers of lists and prices ofcomparative insurance policies was seen by manyas a very useful contribution that could be madeby press freedom organisations (18) .Challenges for freelancersThe issues of employers merely buying finishedcopy, not giving freelancers an advance, andabrogating responsibility if they get intotrouble while in the field were also major gripesarticulated. This is a significant concern, as itleaves the journalist without a safety net and withno burden shouldered by the employer if thingsdo not go as planned. Sometimes, freelancersfeel that they should produce content first andpitch the story to news outlets later, but this is notnecessarily advisable. As one of the journalists atthe conference, who also commissions work fromfreelancers for the news outlet she works for, putit: “I worry if [journalists pitching a story] don’task what the rates are and negotiate terms ofemployment before going into the field. It callstheir professionalism into question.”The session concluded with input from therepresentatives of the different press freedomorganisations attending the conference, brieflyoutlining some of the ways their organisationscan be of assistance to journalists, particularlyfreelance journalists.The Committee to Protect Journalists can offergood advice on the do’s and don’ts of warreporting. CPJ maintains a small distress fundthrough which it dispenses emergency grants tojournalists. CPJ steps in when journalists are indire situations as a result of persecution for theirwork, helps them get medical care and evacuatesjournalists at risk to temporary havens. The RoryPeck Trust, meanwhile, provides direct financialassistance to freelancers and their families in crisisaround the world. RPT also provides bursariesfor freelancers to undertake hostile environmenttraining through approved providers, and supportsfreelancers with practical advice, information andresources on insurance, safety and welfare issues.Although, as the representative stated clearly, the“supply of funds for security training programsreally does not meet the demand.” Reporterswithout Borders, for its part, dispenses servicessimilar to CPJ’s and loans protective equipmentto journalists, provides discounted insurancerates and a free emergency hotline as well aspsychological support. It has also co-produced,17. See http://en.rsf.org/insurance-for-freelance-17-04-2007,21746.html18. On 17 June 2013, the International News Safety Institute published a document comparing the various insurance packages madeavailable for journalists worldwide. The document is available here:http://www.newssafety.org/images/F<strong>IN</strong>AL%20Insurance%20document%20for%20articleF<strong>IN</strong>AL-HS.pdf19

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from Syriawith the UNESCO, a practical guide for journalists,including those working in conflict zones. (19)SKeyes meanwhile, has funding for some Syriansjournalists and fixers who have been forced outof Syria due to the conflict, and helps themrelocate to other countries. Foreign journalistscan help in this regard by making sure their localcollaborators have valid passports so that pressfreedom organisations assist them in obtainingvisas for safer countries in emergency cases.Key recommendations:Key recommendations from this session are included in Appendix 1: Minimum Working Standards for Journalists inConflict Zones.2019. RWB produced in 2007 a ‘Handbook for Journalists’ going to dangerous locations, in collaboration with UNICEF. It is availablehere: http://en.rsf.org/handbook-for-journalists-17-04-2007,21744.html

Dealing with GovernmentsGovernments and kidnappingsA minority of journalists attending the conferencehad direct dealings with their own governments.In most cases, this involved discussions regardingthe release of kidnapped colleagues. Participantsshared some mixed reviews in this regard abouttheir experiences with security, political anddiplomatic authorities in the Netherlands,Belgium, the UK, Germany, France and Italy.Several journalists called on governments to usetheir technological assets, like Signals Intelligence(or SIG<strong>IN</strong>T) (20) , to trace kidnappers or to at leastdo more on the diplomatic front when it came tonegotiating the release of kidnapped journalists.Many participants said that they have little to nofaith in their government and believe that they canonly rely on colleagues to follow their case, if theyare kidnapped.It is understandable that governments have strictpolicies when dealing with cases of kidnapping.These policies, including contacts with thekidnappers, involvement of special forces andpaying ransoms, are often state secrets. Also,official communication with relatives of kidnappedindividuals is governed by different sets of rulesfrom country to country. But, while governmentsmay not be able to share all details they haveabout a certain case with relatives, the discussionhighlighted the need for a more transparentexplanation of the communication policies andchannels. This is particularly true when smallgroups of journalists are actively working on therelease of their colleagues through contacts basedon the ground, which has happened on numerousoccasions during the Syrian conflict.Visas and entry stampsThe session then moved to more practical aspectsof gaining a visa for regime-controlled areas.Journalists agreed that press is very heavilymonitored and that writing negatively about theregime will almost certainly hamper one’s chancesof getting a second visa. Also, it was recommendednot to reveal one’s intention to cover potentiallysensitive topics on the application form. Onejournalist reported paying a fixer a significantsum to secure a visa, as it did not seem possible toobtain one through regular channels at the time.But, as outlined before, freelancers do not have thesame funds available and therefore often have totake great risks by entering illegally if they want tocover the same stories. Another journalist warnedthat border police is likely to check your computerin Damascus airport prior to your departure, so itis advised to clear or hide sensitive documents.Many participants in the conference weresurprised to learn that Syrian regime officials haddenied entry visas to a number of journalists whohad previously been granted access on the groundsthat they had entered too many times and thatthey ought to let other journalists in for the sakeof fairness. Another commented that the regime isconfident that momentum is now in its favour afterretaking the city of Al-Qussair and other parts ofthe county. As a result, it is becoming more lenientwith visas, but this cannot be verified.There was wide consensus that the Jordanian borderwas deemed very difficult to cross, and, in fact,none of the attendees had crossed the Jordanianborder recently. Entering illegally from Jordan wasalso ill-advised as the border is well controlled,20. SIG<strong>IN</strong>T is a method of intelligence gathering which involves the interception of signals. The sort of SIG<strong>IN</strong>T that the journalistssaid would benefit them in their attempts to secure the release of their kidnapped colleagues includes communications (COM<strong>IN</strong>T)or electronic (EL<strong>IN</strong>T).21

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from Syriaand armed Syrian opposition factions in the areaapparently insist on Jordanian Intelligence givingjournalists prior permission. Additionally, at thetime of the conference, Jordanian officials seemedto be very much opposed to allowing journalists tocross the border into Syria.With regards to Lebanon, journalists were informedof the risks when entering with a Free Syrian Army(or “New Syria”) stamp, as this has in many instancesresulted in interrogation at the airport or refusedentry. However, Lebanon’s General Security hasnot demonstrated any consistent behaviour on thismatter, in the absence of an officially declared policy.There was little concrete information availableabout crossing the Iraqi border into the largelyKurdish north-eastern region of Syria. The last timea journalist at the conference was in the Kurdisharea of Syria was November 2012; she found iteasy to enter but had to queue for hours to leave, asseveral border crossings were closed. Experiencessuch as this highlight the fluid nature of the Syrianconflict. Though, as with other conflict situations,the better the contacts the easier it is to move in andout of Syria as well as within the country.Key recommendations to governments:• Show more transparency about your communication policy with relatives of kidnapped journalists.• Do not ban access to journalists who have non-regime Syrian stamps on their passports.• Provide shelter and assistance to Syrian fixers working with foreign journalists in cases of emergency.• Facilitate the visa process for journalists’ fixers and local collaborators in situations where they are most at risk.22

Dealing with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder“What’s worst is that when you’ve been through all this, you haven’t the capacity to share your experiences with nonjournalists.You feel so much around you is futile and frivolous – it’s hard to adapt to ‘real life’. Especially when you’verecently come back from the war zone.”A participantThe discussion during this session covered strategiesfor dealing with stress on the ground as well asrecognising and dealing with the effects of bothPost-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and lesserstress related conditions.With regard to the former, it emerged thatparticipants deployed a variety of copingmechanisms. For example, many would usedistractions to help them keep their emotions incheck while reporting on particularly brutal orvicious incidents. One video-journalist explainedhow she forced herself to view her camera as akind of defence from the reality taking place onthe ground. For some, it gave them a kind of peaceof mind to know that they had written ‘worstcase scenario’ notes to their loved ones. Though,one veteran war correspondent felt that to dothat would effectively be sealing his fate and hepreferred not to think in such terms.On a related topic, several participants discussedhow they dealt with being both parents and warreporters, and how they justified the decision togo to extremely dangerous areas with dependentsremaining at home. It was not an easy discussionand briefly touched on the often-debated issueof whether working in a dangerous professionof one’s choice is irresponsible or selfish,particularly when the journalist has dependents. (21)PTSD and other conditionsThe discussion then moved to the psychologicalconsequences of witnessing traumatic events and howto cope with them. PTSD, it should be noted, wasrecognised as a severe condition that had first cometo light when US soldiers returning from Vietnam inthe 1960’s and 70’s were found to experience traumarelatedsymptoms, many even in later life.Few participants actually knew how to recognisePTSD as opposed to less severe conditions, suchas burnout, anxiety and cumulative stress. Manywere surprised to learn that, according to the WorldHealth Organisation, PTSD only affects 15.4%of people who have experienced a particularlydisturbing event (22) and is more prevalent amongwomen than men.Several participants described how they copewhen they return from a conflict zone. Difficultiesin relating to non-journalists, particularly as thelatter’s problems often seem trivial when comparedto those in war zones, were mentioned frequently.And, while some suggested that ‘hanging around’with other journalists was the best approach toease oneself gradually back into a ‘normal’ society,others recommended spending time with nonjournalistsas a healthier approach, as it forces adistinction between work and free time.21. This issue is raised in greater detail in a well-circulated radio broadcast. See Kelly McEvers ‘Diary of a Bad Year: A WarCorrespondent’s Dilemma’, NPR, 29 June 2013. Available at:http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2013/06/29/196327290/diary-of-a-very-bad-year.22. ‘Guidelines for the management of conditions specifically related to stress’, World Health Organisation. Available at:http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85119/1/9789241505406_eng.pdf23

Dealing with Post-Traumatic Stress DisorderKey recommendations to journalists:• Have plenty of rest, good food and exercise after your return from the war zone.• Re-establish a routine in your daily life.• Seek counselling and psychological support.• Do not ignore trauma, but do not let it define you.25

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from SyriaConclusionPhoto credit: Patrick Tombola, Two photographers in downtown Aleppo – Syria, October 2012The Syrian conflict has provided a harrowingreminder – if one were needed – of just howdangerous reporting from conflict zones can be. Asof August 2013, according to figures published bythe Committee to Protect Journalists, 56 journalistshave been killed in Syria since the conflict began. (25)The figure includes some of the finest and mostexperienced war journalists of our generation,but it also shows a huge increase in the number offreelancers who have lost their lives. Indeed, of the56 journalists listed, 36% of them were freelancers.This compares with a figure of just 18% in 1992when such data was first collected by CPJ.The increase in the proportion of freelancers instatistics is just one of the most obvious examplesof how journalism has changed in recent years.Unfortunately, the other big development has beena shrinking budget among many, if not most, newsoutlets, with the result that there is now much lessfunding available to pay for content – let alone fortraining and equipment.Nevertheless, a basic level of security has to beestablished for journalists working in conflict zones.It is reasonable to expect that those individualswho report from dangerous environments will bewell prepared, have basic life-saving equipmentand first aid training. As Vaughan Smith, founderof the Frontline Club, puts it: “We have the right toexpect that if we are injured and can be saved thenour colleagues will have the skills to do so.” (26)2625. The number of journalists killed in Syria since March 2011 according to CPJ is available here:http://cpj.org/killed/mideast/syria/. According to RWB, 25 journalists and 67 citizen journalists have lost their lives; numbersavailable here: http://en.rsf.org/syria.html26. ‘Introduction to the Frontline Club Safety Paper’ by Vaughan Smith. Available at http://frontlinefreelance.org/node/50

ConclusionIt is therefore primarily the responsibility of theindividual journalist to ensure he or she hassuch basic training and equipment before goinginto conflict zones. However, it was strongly theview at the conference that employers also havea responsibility to assist journalists in that respectby providing the equipment and by covering thecost of training staff reporters. It was felt thatemployers should likewise contribute to the effortsof freelancers to adopt the most important safetybehaviour and have adequate equipment. Such acommitment would save lives, prevent a situationwhere well qualified and experienced people arebeing driven away from the industry and, at thesame time, contribute towards maintaining highjournalistic standards.Other industries have seen groups of employeesrally together and, through collective bargaining,effect change and implement basic standardsthat improve both working conditions and staffsecurity. The news industry has been slow to dothe same.There is no shortage of awareness of the challengeswithin the industry, and, as set out above, thereare impressive initiatives by a multitude oforganisations to bring about improvements in theworking conditions of journalists. But, these effortsneed to be synchronised, and employers need tobe brought on board to ensure that minimumworking standards are established across theindustry. This is the challenge that lies ahead, butit is not insurmountable.First, practitioners need to agree on a set of minimumstandards to be observed by both journalists andemployers. This has been one of the key purposes ofthe three-day retreat sponsored by the Samir KassirFoundation. It is then up to journalists themselvesto drive this change forward. Collective bargainingdoes work, and, once a collective spirit materialisesamong journalists not to accept poor workingconditions, it is hoped that pressure can be builton employers to agree to such minimum standards.The campaign will need to show employers thatthey too will benefit from such an agreement; thatit is in their interest to keep journalists safe and toensure they have the means to do their job effectively.Moreover, media outlets that gain the reputationof being concerned for staff welfare will inevitablyattract better journalists. Also, both press freedomorganisations and governments have a role to play byproviding improved levels of support for journalistsand by ensuring that safety standards that apply forother sectors are implemented immediately withinnews organisations.There is no doubt that reporting from conflict zonesserves the public interest, a fact that is sometimeslost as the focus is put on more commercial, trivialnews. War reporters often lay the foundations forhow history will be written and events remembered.At the best of times, war correspondents have hada positive impact on policy decisions and providedwitness accounts for criminal proceedings; crimesfor which the perpetrators would never havebeen brought to justice otherwise. Such reportinghelps cut through opposing, often propagandistic,narratives and present facts as they really are. Itis in society’s interest to maintain the quality ofjournalism, and, by extension, it is in society’sinterest to have minimum working standards forall journalists working in conflict zones.27

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from SyriaAPPENDIX 1Minimum Working Standards forJournalists in Conflict ZonesBackgroundOn the weekend of 12-14 July 2013, some 45journalists gathered in Beit Mery, Lebanon,with representatives from top internationalpress freedom organisations to discuss thechallenges faced by reporters in conflict zones,with a particular focus on Syria. Attending theconference were staff journalists from medium tolarge news organisations and freelance journalistswith vastly different amounts of experience andrepresenting a cross section of media – fromprint to photo journalists, documentary makersand radio reporters. Together, they were taskedwith coming up with a document articulating theminimum working standards for every journalistcovering conflict, whether staff journalist orfreelancer. The document, which is presentedbelow, includes recommendations to employersand to the journalists themselves.Recommendations to employers- Ensure the journalist possesses adequateprotective gear and communicationequipment, appropriate to the conflict zoneand in line with recommendations from pressfreedom organisations. (27)- Cover communications expenses incurred bythe journalist in accordance with pre-establishedlimitations agreed upon by both parties.- Ensure the journalist has undergoneappropriate medical and safety training.- Ensure the journalist has insurance to a levelappropriate to the conflict zone he/she isreporting from, in line with recommendationsfrom press freedom organisations.- Pre-establish a communications plan withthe journalist. Typically, this consists of thejournalist checking in with a designatedperson at a designated time in order to quicklyrecognise if a journalist is in trouble, missing orkidnapped, and deal accordingly.- Possess the contact details of the journalist’semergency contact. This person should havethe contact details of the journalist’s familyand access to documents the journalist hasauthorised the employer to read in case ofsuspicion or confirmation of kidnap or death.- Provide the journalist with a written copy ofthe terms of employment.- Provide journalists with access to emergencyfunds to cover any expected or unexpectedcosts of working in a war zone. (28)- Refuse to pay sources interviewed by journalists.- Encourage debriefings between editors andjournalists after the reporter has emerged froma conflict zone. During such meetings, editorsshould be updated on the latest security issueswithin the country and remind journaliststhat there are anonymous, non-judgmentalcounselling services available. (29)2827. These include, but are not limited to, encryption for communication devices, satellite phones, headgear, body protection and first aid.28. This may include, but is not limited to, backup equipment due to high probability of a lack of electricity and Internet access, fixers,translators and drivers.29. Some organisations implement mandatory counselling for employees returning from war zones. This should be seriously consideredby news organisations.

APPENDIX 1Recommendations to journalists• Before going to the field, journalists should:- Get adequate insurance and suitablevaccinations, in line with recommendationsfrom press freedom organisations.- Get proper safety, communications, first aidequipment and post-rape kit.- Undergo trainings relevant to the conflictarea, in line with recommendations from pressfreedom organisations. (30)- Have a communications plan with theemployer and/or a trusted third party who isknown to the employer.- Provide a trusted contact with access to andcopies of emergency numbers, passportdetails, insurance details, press card, will andother necessary details in the event of aninjury, kidnapping or death.- Know how much he/she will get paid perstory.- Read his/her contract(s).- Take the time to prepare, research and planthe trip adequately.- Understand how to secure informationin communication devices so that his/hersecurity and that of third parties will not becompromised if the journalist is apprehendedor interrogated by a potentially unfriendlyparty.• In the field, journalists should:- Behave conscientiously and respectfully. (31)- Respect his/her fixers and agree on detailsregarding payment (including timing, amountand method) before work is carried out.- Not pay for information received fromsources.- Be conscious not to stay too long in oneplace and in the conflict zone in general, as itincreases risk factors.- Be aware that communications can beintercepted and adapt behaviour to minimiserisk. This includes, but is not limited to,removing SIM cards when mobile phonesare not in use; being careful not to revealinformation that might compromise thecurrent or future locations of the journalistand his/her contacts; being ready to movelocation after using phones, including satellitephones.• After reporting from a conflict zone,journalists should:- Undergo a debriefing with his/her employer.- Check up on fixers, if it is safe to do so, andensure payment for work done.- Not be afraid to seek psychological support.30. This includes, but is not limited to, safety, first aid and communications encryption.31. This includes, but is not limited to, showing awareness and appreciation for different cultures, reflected through adhering to normaldress codes and attitudes.29

Journalists’ Security in War Zones: Lessons from SyriaAPPENDIX 2Recommendations to Press FreedomOrganisations- Prepare updated documents, made availableonline, that outline a range of different issuesof concern to journalists operating in conflictzones. These include, but are not limited to:• Types of insurance (including pricing)• Types of trainings (including pricing)• Information on safety andcommunications equipment (includingprice and sales points)• Information on psychological support,treatment and advice centres- Organise regular meetings with media outletsto raise awareness about safety in the field.- Organise regular and affordable hostileenvironment, online security and first aidtrainings for journalists.- Set up a collection point close to countriesin conflict so that journalists can rent/buynecessary equipment (including bullet-proofjackets, helmets, satellite, trackers, etc.).- Cooperate with journalists, news outlets andmedia professionals’ unions to compile a list ofrates paid by news outlets for freelance content.30

©2013 Samir Kassir FoundationAddress: 63 Zahrani Street, Sioufi, Ashrafieh, Beirut – LebanonTel/Fax: (961)-1-397331Email: info@skeyesmedia.orghttp://www.skeyesmedia.orgThis project is funded by theEUROPEAN UNIONThe contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the Samir Kassir Foundation and can in no way be taken to reflect the viewsof the European Union.The views expressed in this report are the sole responsibility of the Samir Kassir Foundation and do not necessarily reflect the officialpositions of Reporters Without Borders, the Rory Peck Trust and the Committee to Protect Journalists.Graphic design: Jamal Awada