Marsha Warren's Caldwell Award Acceptance Speech

Marsha Warren's Caldwell Award Acceptance Speech

Marsha Warren's Caldwell Award Acceptance Speech

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

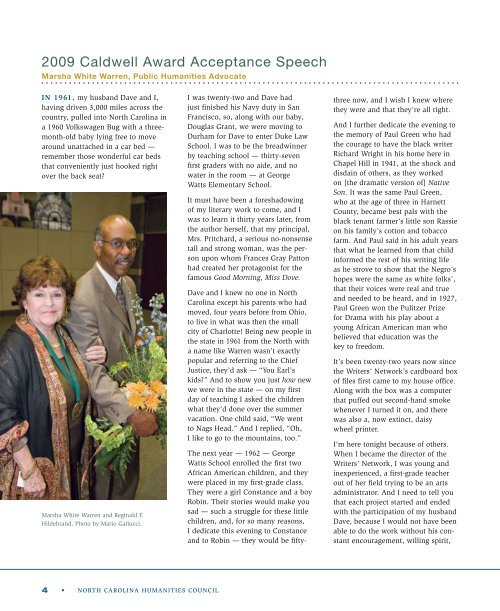

2009 <strong>Caldwell</strong> <strong>Award</strong> <strong>Acceptance</strong> <strong>Speech</strong><strong>Marsha</strong> White Warren, Public Humanities AdvocateIn 1961, my husband Dave and I,having driven 3,000 miles across thecountry, pulled into North Carolina ina 1960 Volkswagen Bug with a threemonth-oldbaby lying free to movearound unattached in a car bed —remember those wonderful car bedsthat conveniently just hooked rightover the back seat?<strong>Marsha</strong> White Warren and Reginald F.Hildebrand. Photo by Mario Gallucci.I was twenty-two and Dave hadjust finished his Navy duty in SanFrancisco, so, along with our baby,Douglas Grant, we were moving toDurham for Dave to enter Duke LawSchool. I was to be the breadwinnerby teaching school — thirty-sevenfirst graders with no aide, and nowater in the room — at GeorgeWatts Elementary School.It must have been a foreshadowingof my literary work to come, and Iwas to learn it thirty years later, fromthe author herself, that my principal,Mrs. Pritchard, a serious no-nonsensetall and strong woman, was the personupon whom Frances Gray Pattonhad created her protagonist for thefamous Good Morning, Miss Dove.Dave and I knew no one in NorthCarolina except his parents who hadmoved, four years before from Ohio,to live in what was then the smallcity of Charlotte! Being new people inthe state in 1961 from the North witha name like Warren wasn’t exactlypopular and referring to the ChiefJustice, they’d ask — “You Earl’skids?” And to show you just how newwe were in the state — on my firstday of teaching I asked the childrenwhat they’d done over the summervacation. One child said, “We wentto Nags Head.” And I replied, “Oh,I like to go to the mountains, too.”The next year — 1962 — GeorgeWatts School enrolled the first twoAfrican American children, and theywere placed in my first-grade class.They were a girl Constance and a boyRobin. Their stories would make yousad — such a struggle for these littlechildren, and, for so many reasons,I dedicate this evening to Constanceand to Robin — they would be fiftythreenow, and I wish I knew wherethey were and that they’re all right.And I further dedicate the evening tothe memory of Paul Green who hadthe courage to have the black writerRichard Wright in his home here inChapel Hill in 1941, at the shock anddisdain of others, as they workedon [the dramatic version of] NativeSon. It was the same Paul Green,who at the age of three in HarnettCounty, became best pals with theblack tenant farmer’s little son Rassieon his family’s cotton and tobaccofarm. And Paul said in his adult yearsthat what he learned from that childinformed the rest of his writing lifeas he strove to show that the Negro’shopes were the same as white folks’,that their voices were real and trueand needed to be heard, and in 1927,Paul Green won the Pulitzer Prizefor Drama with his play about ayoung African American man whobelieved that education was thekey to freedom.It’s been twenty-two years now sincethe Writers’ Network’s cardboard boxof files first came to my house office.Along with the box was a computerthat puffed out second-hand smokewhenever I turned it on, and therewas also a, now extinct, daisywheel printer.I’m here tonight because of others.When I became the director of theWriters’ Network, I was young andinexperienced, a first-grade teacherout of her field trying to be an artsadministrator. And I need to tell youthat each project started and endedwith the participation of my husbandDave, because I would not have beenable to do the work without his constantencouragement, willing spirit,4 • North Carolina Humanities Council

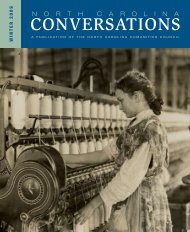

Storyteller Joyce Grear in a dramatic interpretationof Harriet “Moses” Tubman at the<strong>Caldwell</strong> celebration. Photo by Mario Gallucci.and, for moving filing cabinets andboxes of books, his strong muscles.But he would tell me all the timethat he was the one who benefitedbecause he much preferred beingaround my colleagues, the writers,far better than his own, the lawyers!It was when I began writing grantapplications to the North CarolinaArts Council, in the 80s, that Ilearned the lessons and the wisdomof diversity and inclusiveness.How many people of color do youhave in your organization?How many on staff?How many people of color do youserve in your programming?What accommodations are youmaking for people with physicalchallenges?Thanks to the Arts Council, for showingus how and why to be inclusive.And special thanks to them for thatgrant many years ago to build a rampat White Cross School so my boardmember Marty Silverthorne could getin the building to attend meetings!When we discovered at the Writers’Network that there were only elevenblack writers on our database, weapproached the Z. Smith ReynoldsFoundation and they funded theBlack Writers Identification Program.By the end of the project we had 350writers identified in North Carolina— some we knew who only had thatone hand-written poem in the pocketof her apron that she was anxious toshare. And the next year, we wentback to ZSR with a program to identifythe Native American voices inour state, and they funded that one,too. You may not know that NorthCarolina has more Native Americansthan any state east of the Mississippi— with our eight tribes includingHalawi-Saponi like Dreamweaver —a Woodland Indian.Because of The Paul GreenFoundation and the Mary DukeBiddle Foundation, we [at theWriters’ Network] were able todevelop writing programs in prisons,shelters, retirement homes,and hospital settings. We had fiveprograms going simultaneously inCentral Prison including one forDeath Row prisoners. All participantsat the prison were complimentarymembers of the Network, and one ofour most troubled members workedwith his Network instructor rightup until the time he was executed.Thanks sincerely to the Green andBiddle Foundations for continuing toprovide grants each year for projectsthat enrich the lives of so many.Special recognition and thanks to theDepartment of Cultural Resourcesand then-secretary Betty Ray McCainfor granting funds for the establishmentof the North Carolina LiteraryHall of Fame in 1996.And throughout my tenure with theseorganizations and still today, for mewith Weymouth Center programs,always and always the NorthCarolina Humanities Council providesfinancial and invaluable handsonsupport from the dedicated andbright staff for numerous programsto numerous organizations.The point is that these foundationsand agencies don’t just providefunding. They offer opportunitiesfor organizations to mature in theirunderstanding of the importanceof reaching out — to serve all thepeople. All of them.Individuals and corporations are alsovital to the well-being of nonprofits.I remember the time when we hadno money to do the newsletter, Iwent over to visit Frank Daniels, andthe News & Observer sponsored theNetwork News [the newsletter of theWriters’ Network] for three years —then Frank handed us off to RolfeNeill at the Charlotte Observer forthree years and then we were handedoff to the Winston-Salem Journal.With each poem we recite,each child we teach, eachramp we install, eachaudience we build, eachperson we empower to telltheir story, we keep theplanet from becoming adesert with our languageand literature....And now, I’ve embarked on a newjourney with extraordinary NorthCarolinians to build a monument tofreedom in our state capital that honorsthe African American experienceand their struggle for freedom. And,as you would expect, this projectNC Conversations • Winter • Spring 2010 • 5

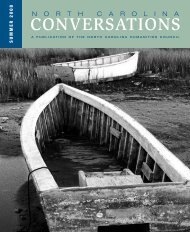

is funded generously, again by all these foundations andagencies I’ve mentioned: the North Carolina HumanitiesCouncil, ZSR, Green and Biddle Foundations, Arts Council,and the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.It seems this freedom journey began for me when, as ahigh school girl in Dayton, Ohio, in the early 50s, I wasnamed president of the Y-Teens and, together with anotherofficer, a black girl named Beverly, we would be sent thatsummer to an Ohio college campus for leadership training.“How about if we have a picnic along the way,” said mymother, who would drive Beverly and me to the collegeto stay for the week. And, as a sheltered girl, I didn’tfigure it out until years later that my mother was worriedthat Beverly might not be served in a restaurant alongthe route.I wouldn’t really understand until 1963 when my husbandDave, with two-year-old Doug on his shoulders, andI walked in a silent march down the middle of FranklinStreet in Chapel Hill as we pointed our fingers towardrestaurants that would not serve blacks.This summer in Southern Pines, the Weymouth Center forthe Arts & Humanities, on whose board I serve, offered awriting camp for children. Knowing that there would bekids whose families couldn’t afford the $30 tuition, scholarshipswere made available. Listen to excerpts from thepoems of these two little girls — listen to their clarioncall, their claim of the human spirit.I have a memory of my Grandma.She taught me how to read.We practiced every day.My name is Destiny Sumon Griffin.It means I believe in being a writer one day.My Name by Antoinette McGeeAntoinette means beautiful, wonderful and thoughtful.It is like the sky. It is like when I talk to my daddy.It is the memory of my Grandpa Georgie who taughtme how to be honest and how to joke; when he taughtme how to be brave and to face my fears.My name is Antoinette McGee. It means if I wantsomething, I will go for it.If I can’t get it, I will keep trying.Veronique Vienne, in The Art of Doing Nothing, writes,“Apparently one of our functions on this earth is to be gardeners— unwilling caretakers of a fragile ecosystem. Wemay be detrimental to the environment in other ways, butwhen we empty our lungs, we help make the grass grow<strong>Marsha</strong> and David Warren with son Doug at a protest march inChapel Hill, 1963. Photo courtesy of the North Carolina Collection,UNC Chapel Hill.greener. With our breath, we keep the planet frombecoming a desert.”The metaphor is resounding. With each poem we recite,each child we teach, each ramp we install, each audiencewe build, each person we empower to tell their story, wekeep the planet from becoming a desert with our languageand literature; our art and culture, our humanities, ourhuman experience and our absolutely vital requirementfor freedom.I can’t imagine any state I’d rather have pulled intoin 1961 in my Volkswagen Bug than North Carolina.6 • North Carolina Humanities Council