You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

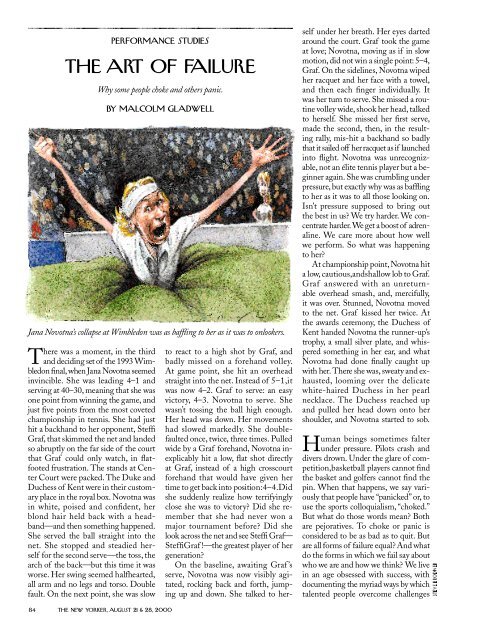

and obstacl e s . T h e re is as mu ch to bel e a rn e d ,t h o u g h ,f rom documenting them yriad ways in which talented peoples ometimes fail.“ C h ok i n g” sounds like a vague anda ll - e n c ompassing term , yet it describesa ve ry specific kind of f a i l u re .For exampl e, p s ychologists often use a pri m i t i vevideo game to test motor skill s .T h ey’llsit you in front of a computer with as c reen that shows four boxes in a row,and a keyb o a rd that has four corresp onding buttons in a row. One at at i m e, x’s start to appear in the boxes onthe scre e n , and you are told that eve rytime this happens you are to push thek ey corre s p onding to the box . Ac c o rdingto Daniel Wi ll i n g h a m ,a psych o l o-gist at the Unive r s i ty of Vi r g i n i a , i fyo u’re told ahead of time about thep a t t e rn in which those x’s will appear,your re a c t i on time in hitting the ri g h tk ey will improve dra m a t i ca lly. Yo u’llp l ay the game ve ry ca re f u ly for a fewro u n d s , until yo u’ve learned the sequ e n c e, and then yo u’ll get faster andf a s t e r. Wi llingham ca lls this “e x p l i c i tl e a rn i n g. ”But suppose yo u’re not toldthat the x’s appear in a regular sequence,and even after playing the game for awhile yo u’re not a w a re that there is ap a t t e rn .Yo u’ll s t i l lget faster: yo u’ll learnthe sequence uncon s c i o u s ly. Wi ll i n g-ham ca lls that “implicit learn i n g” —l e a rning that takes place outside ofa w a re n e s s .These two learning sys t e m sa re quite separa t e, based in diffe re n tp a rts of the bra i n .Wi llingham says thatwhen you are first taught som e t h i n g —s ay, h ow to hit a backhand or an ove r-head fore h a n d —you think it throughin a ve ry delibera t e, m e ch a n i cal manne r. But as you get better the implicits ystem takes ove r : you start to hit ab a ckhand flu i dly, without thinking.Thebasal ganglia, w h e re implicit learn i n gp a rt i a lly re s i d e s , a re c on c e rned withf o rce and timing,and when that sys t e mk i cks in you begin to develop touch anda c c u ra cy, the ability to hit a drop shot orplace a serve at a hundred miles perh o u r.“This is something that is going tohappen gra d u a lly, ” Wi llingham says .“You hit seve ral thousand fore h a n d s ,a fter a while you may still be attendingto it. But not ve ry mu ch .In the end, yo ud on’t re a lly notice what your hand isdoing at all . ”Under con d i t i ons of s t re s s ,h ow eve r,the explicit system sometimes takes ove r.T h a t’s what it means to ch ok e .Wh e nJana Novotna faltered at Wi m b l e d on ,i twas because she began thinking abouther shots again. She lost her flu i d i ty, h e rt o u ch .She double-faulted on her serve sand mis-hit her ove rh e a d s ,the shots thatdemand the greatest sensitivity in forc eand timing. She seemed like a diffe re n tp e r s on — p l aying with the slow, ca u t i o u sd e l i b e ra t i on of a beginner—beca u s e, ina sense, she w a s a beginner again: s h ewas re lying on a learning sys t e m thatshe hadn’t used to hit serves and ove r-head forehands and voll eys since shewas first taught tennis, as a ch i l d .T h esame thing has happened to ChuckK n o b l a u ch ,the New Yo rk Ya n k e e s ’s e c-ond baseman, who inexplica b ly has hadt rouble throwing the ball to first base.Under the stress of p l aying in front off o rty thousand fans at Yankee St a d i u m ,K n o b l a u ch finds himself reve rting toexplicit mode, t h rowing like a LittleLeaguer again.Panic is something else altogether.C onsider the foll owing account of ascuba-diving accident, recounted to meby Ephimia Morph ew,a human-factorsspecialist at N AS A:“It was an open-waterc e rt i fica t i on dive, M on t e rey Bay, C a l i-f o rn i a ,about ten years ago. I was ninete e n .I’d been diving for two weeks.T h i swas my first time in the open oceanwithout the instru c t o r. Just my buddyand I. We had to go about forty fe e td ow n ,to the bottom of the ocean, a n ddo an exe rcise where we took our re g u l a-tors out of our mouth,p i cked up a spareone that we had on our ve s t ,and pra c-ticed breathing out of the spare . M ybuddy did hers. Then it was my turn .I re m oved my re g u l a t o r. I lifted up mys e c on d a ry re g u l a t o r. I put it in mym o u t h ,e x h a l e d ,to clear the lines, a n dthen I inhaled,a n d ,to my surp ri s e,it wasw a t e r. I inhaled water. Then the hosethat connected that mouthpiece to myt a n k ,my air sourc e, came unlatched andair from the hose came exploding intomy face.“Right away, my hand re a ched outfor my part n e r’s air supply, as if I wasgoing to rip it out. It was withoutt h o u g h t . It was a phys i o l o g i cal resp on s e . My eyes are seeing my handdo something irre s p on s i b l e .I’m fig h t-ing with mys e l f. D o n’t do it. Then Is e a rched my mind for what I couldTHE NEW YO R K E R, AUG UST 21 & 28, 2000 8 5

d o. And nothing came to mind. A ll Icould remember was one thing: I f yo uca n’t take ca re of yo u r s e l f, let yo u rbuddy take ca re of yo u . I let my handf a ll back to my side, and I just stoodt h e re . ”This is a textb o ok example of p a n i c .In that mom e n t , M o rph ew stoppedt h i n k i n g. She forgot that she had anothersource of a i r, one that workedp e rfe c t ly well and that,m oments before,she had taken out of her mouth. Shef o r got that her partner had a workingair supply as well , w h i ch could easilybe share d , and she forgot that gra b b i n gher part n e r’s regulator would imperi lboth of t h e m .A ll she had was her mostbasic instinct: get air. St ress wipes outs h o rt - t e rm memory. People with lotso f e x p e rience tend not to panic, b e -cause when the stress suppresses theirs h o rt - t e rm memory t h ey still have som eresidue of e x p e rience to draw on . B u twhat did a novice like Morph ew have? Is e a rched my mind for what I could do. An dnothing came to mind.Panic also causes what psych o l o g i s t sca ll perceptual narrow i n g. In one study,f rom the early seve n t i e s , a group ofsubjects were asked to perf o rm a visualac u i ty task while undergoing whatt h ey thought was a sixty-foot dive ina pre s s u re ch a m b e r. At the same time,t h ey were asked to push a buttonw h e n ever they saw a small light fla s hon and off in their peri ph e ral vision .The subjects in the pre s s u re ch a m b e rhad mu ch higher heart rates than thec on t rol gro u p, i n d i cating that theyw e re under stre s s .That stress didn’t affecttheir accura cy at the visual-acuityt a s k ,b u tt h ey were on ly half as good asthe con t rol group at picking up thep e ri ph e ral light. “You tend to focus orobsess on one thing, ” M o rph ew says .“T h e re’s a famous airplane example,w h e re the landing light went off, a n dthe pilots had no way of k n owing if t h elanding gear was dow n . The pilotsw e re so focussed on that light that noone noticed the autopilot had been disen g a g e d , and they crashed the plane.”M o rph ew re a ched for her buddy’s airs u p p ly because it was the on ly air supply she could see.Pa n i c , in this sense, is the oppositeo f ch ok i n g. C h oking is about thinkingtoo mu ch . Panic is about thinkingtoo little. C h oking is about loss o f i n-s t i n c t . Panic is reve r s i on to instinct.T h ey may look the same, but they arew o rlds apart .Why does this distinction matter?In some instances, it doesn’tmu ch .I f you lose a close tennis match ,i t’s of little moment whether you ch ok e dor panick e d ; either way, you lost. B u tt h e re are cl e a rly cases when h o w f a i l u rehappens is central to understanding w h yf a i l u re happens.Ta k ethe plane crash in which John F.K e n n e d y, J r. , was killed last summer.The details of the flight are well know n .On a Fri d ay evening last July, Kennedyt o ok off with his wife and sister-inlawfor Mart h a’s Vi n ey a rd .The nightwas hazy, and Kennedy flew along theC onnecticut coastline, using the trail oflights below him as a guide. At We s -t e rly, Rhode Island, he left the shore -l i n e, heading straight out over RhodeIsland So u n d ,and at that point, a p p a r-e n t ly disoriented by the darkness andh a ze, he began a series of c u rious mane u ve r s : He banked his plane to theri g h t , f a rther out into the ocean, a n dthen to the left . He climbed and desc e n d e d .He sped up and slowed dow n .Just a few miles from his destination ,Kennedy lost con t rol of the plane, andit crashed into the ocean.K e n n e d y’s mistake,in tech n i cal term s ,was that he failed to keep his wings leve l .That was cri t i ca l ,b e cause when a planebanks to one side it begins to turn andits wings lose some of their ve rt i call i ft . Le ft unch e ck e d ,this process accelera t e s .The angle of the bank incre a s e s ,the turn gets sharper and sharp e r, a n dthe plane starts to dive tow a rd theg round in an eve r - n a r rowing cork s c rew.Pilots ca ll this the gra vey a rd spira l .An dw hy didn’t Kennedy stop the dive? Becau s e, in times o f l ow visibility and highs t re s s , keeping your wings leve l — i n-d e e d ,even knowing whether you are in ag ra vey a rd spira l — t u rns out to be surpri s i n g ly diffic u l t .Kennedy failed underp re s s u re .Had Kennedy been flying during thed ay or with a clear moon ,he would havebeen fin e . I f you are the pilot, l o ok i n gs t raight ahead from the cock p i t , t h eangle of your wings will be obvious fromthe straight line of the hori zon in fronto f yo u . But when it’s dark outside theh o ri zon disappears. T h e re is no exter-8 8 THE NEW YO R K E R, AUG UST 21 & 28, 2000

ing out of the dive .O n ly now did I fe e lthe full force of the G-load, p u s h -ing me back in my seat. “You feel noG-load in a bank,” La n g ew i e s che said.“T h e re’s nothing more confusing forthe uninitiated.”I asked La n g ew i e s che how mu chl onger we could have fall e n .“Within fives e c on d s ,we would have exceeded thelimits of the airp l a n e, ” he re p l i e d , b yw h i ch he meant that the force of t ry -ing to pull out of the dive would haveb roken the plane into pieces. I look e da w ay from the instruments and askedLa n g ew i e s che to spira l - d i ve again, t h i stime without telling me.I sat and waited.I was about to tell La n g ew i e s che thathe could start diving anyt i m e, w h e n ,s u d d e n ly, I was thrown back in mych a i r. “We just lost a thousand fe e t ,”he said.This inability to sense, e x p e ri e n t i a ly, lwhat your plane is doing is what makesnight flying so stre s s f u l . And this wasthe stress that Kennedy must have fe l twhen he turned out across the water atWe s t e rly, leaving the guiding lights ofthe Connecticut coastline behind him.A pilot who flew into Na n t u cket thatnight told the Na t i onal Tra n s p o rt a t i onSa fe ty Board that when he descendedover Mart h a’s Vi n ey a rd he looked dow nand there was “nothing to see. T h e rewas no hori zon and no light. . . . Ithought the island might [have] suffered a power failure .” Kennedy wasn ow blind, in eve ry sense, and he mu s th a ve known the danger he was in. H ehad ve ry little experience in flyi n gs t ri c t ly by instru m e n t s . Most of t h etime when he had flown up to theVi n ey a rd the hori zon or lights hads t i ll been visible. T h a t s t ra n g e, final sequenceof m a n e u vers was Kennedy’sf rantic search for a cl e a ring in the haze .He was trying to pick up the lights ofM a rt h a’s Vi n ey a rd , to re s t o re the losth o ri zon . B e tween the lines of the Nati onal Tra n s p o rt a t i on Sa fe ty Board’s repo rt on the cra s h , you can almost fe e lhis despera t i on :About 2138 the target began a right turnin a southerly direction. About 30 secondsl a t e r, the target stopped its descent at 2200feet and began a climb that lasted another 30seconds. During this period of time, the targ e tstopped the turn, and the airspeed decre a s e dto about 153 KIAS. About 2139, the targ e tleveled off at 2500 feet and flew in a southeasterlydirection. About 50 seconds later,the target entered a left turn and climbed to2600 feet. As the target continued in the leftt u rn, it began a descent that reached a rate ofabout 900 fpm.But was he ch oking or panick i n g ?H e re the distinction between those tw ostates is cri t i ca l .Had he ch ok e d ,he wouldh a ve reve rted to the mode of e x p l i c i tl e a rn i n g. His movements in the cock -pit would have become mark e dly slow e rand less flu i d .He would have gone backto the mech a n i ca l ,s e l f - c onscious applicat i on of the lessons he had first re c e i ve das a pilot—and that might have beena good thing. Kennedy n e e d e dto think,to con c e n t rate on his instru m e n t s , t ob reak away from the instinctive flyi n gthat served him when he had a visiblehori zon .But instead, f rom all appeara n c e s ,he panick e d . At the moment when heneeded to remember the lessons he hadbeen taught about instrument flyi n g,his mind—like Morph ew’s when shewas underw a t e r — must have gon eb l a n k .Instead of rev i ewing the instrume n t s ,he seems to have been focussedon one question : Wh e re are the lightso f M a rt h a’s Vi n ey a rd? His gyro s c o p eand his other instruments may wellh a ve become as invisible as the peri pheral lights in the underwater-panic expe ri m e n t s . He had fallen back on hisi n s t i n c t s — on the way the plane f el t—and in the dark , o f c o u r s e, instinct ca nt e ll you nothing. The N.T. S . B . re p o rts ays that the last time the Pi p e r’s wingsw e re level was seven seconds past 9:40,and the plane hit the water at about9 : 4 1 ,so the cri t i cal period here was lessthan sixty secon d s . At tw e n ty - five secondspast the minute, the plane wastilted at an angle greater than forty - fived e g re e s . Inside the cockpit it wouldh a ve felt norm a l . At some point, K e n-nedy must have heard the rising windo u t s i d e, or the roar of the engine asit picked up speed. A g a i n , re lyingon instinct, he might have pulled backon the stick , t rying to raise the noseo f the plane. But pulling back on thes t i ck without first leve lling the wingson ly makes the spiral tighter and thep roblem worse. I t’s also possible thatKennedy did nothing at all ,and that hewas fro zen at the con t ro l s ,s t i ll fra n t i-ca lly searching for the lights of t h eVi n ey a rd ,when his plane hit the water.9 0 THE NEW YO R K E R, AUG UST 21 & 28, 2000

Sometimes pilots don’t even try to makeit out of a spiral dive . La n g ew i e s ch eca lls that “one G all the way dow n . ”What happened to Kennedy thatnight ill u s t rates a second majord i f fe rence between panicking and ch okin g. Pa n i cking is conve n t i onal failure, o fthe sort we tacitly understand. K e n n e d yp a n i cked because he didn’t know enoughabout instrument flyi n g. I f h e’d had anotheryear in the air, he might not havep a n i ck e d ,and that fits with what we beli eve—that perf o rmance ought to improve with experi e n c e, and that pre s s u reis an obstacle that the diligent can ove r-c om e .But ch oking makes little intuitives e n s e .Nov o t n a’s problem wasn’t lack ofd i l i g e n c e ; she was as superb ly con d i-t i oned and schooled as anyone on thetennis tour.And what did experience dofor her? In 1995, in the third round ofthe Fre n ch Open, Novotna ch oked eve nm o re spectacularly than she had againstG ra f, losing to Chanda Rubin after surren d e ring a 5–0 lead in the third set.T h e re seems little doubt that part ofthe re a s on for her collapse against Ru -bin was her collapse against Gra f — t h a tthe second failure built on the fir s t ,making it possible for her to be up 5–0in the third set and yet entertain thethought I can still lose. I f p a n i cking isc onve n t i onal failure,ch oking is para d oxical failure .Claude St e e l e,a psychologist at St a n-f o rd Unive r s i ty, and his colleagues haved one a number of e x p e riments in re c e n tyears looking at how certain groups perfo rm under pre s s u re, and their fin d i n g sgo to the heart of what is so stra n g eabout ch ok i n g.Steele and Joshua Aronson found that when they gave a gro u po f St a n f o rd undergraduates a standardized test and told them that it was am e a s u re of their intellectual ability, t h ewhite students did mu ch better thantheir black counterp a rt s .But when thesame test was presented simply as an abst ract labora t o ry tool, with no re l ev a n c eto ability,the scores of b l a cks and whitesw e re virt u a ly identica l .Steele and Aronson attribute this dispari ty to what theyca ll “s t e re o type thre a t” :when black studentsare put into a situation where theya re dire c t ly con f ronted with a stere o -type about their group—in this ca s e,one having to do with intell i g e n c e— t h eresulting pre s s u re causes their perf o r-mance to suffe r.Steele and others have found stere o-type threat at work in any situationw h e re groups are depicted in negativew ays .G i ve a group of q u a l i fied wom e na math test and tell them it will measuretheir quantitative ability and they’ll domu ch worse than equally skilled menw i ll ; p resent the same test simply as are s e a rch tool and they’ll do just as wellas the men. Or consider a handful ofe x p e riments conducted by one ofSt e e l e’s former graduate students, J u l i oG a rc i a ,a pro fessor at Tu fts Unive r s i ty.G a rcia gathered together a group ofw h i t e, athletic students and had a whitei n s t ructor lead them through a serieso f phys i cal tests: to jump as high ast h ey could, to do a standing bro a dj u m p, and to see how many pushupst h ey could do in tw e n ty secon d s . T h ei n s t ructor then asked them to do thetests a second time, a n d , as yo u’d expe c t ,G a rcia found that the students dida little better on each of the tasks thes e c ond time aro u n d . Then Garcia rana second group of students throughthe tests, this time replacing the inst ructor between the first and secon dt rials with an Afri ca n - Am e ri ca n .Nowthe white students ceased to improveon their ve rt i cal leaps. He did the expe riment again, on ly this time he replacedthe white instructor with a blacki n s t ructor who was mu ch taller andheavier than the previous black instru c-t o r. In this tri a l , the white students actu a lly jumped less high than they hadthe first time aro u n d . Their perf o r-mance on the pushups, t h o u g h , wasu n changed in each of the con d i t i on s .T h e re is no stere o typ e, a fter all ,that suggeststhat whites ca n’t do as many pushupsas black s .The task that was affe c t e dwas the ve rt i cal leap, b e cause of w h a tour culture says : w h i te men ca n’t jump.It doesn’t come as new s , o f c o u r s e,that black students are n’t as good at testtakingas white students, or that whitestudents are n’t as good at jumping asb l a ck students. The problem is thatTHE NEW YO R K E R, AUG UST 21 & 28, 2000 9 1

w e’ve alw ays assumed that this kind off a i l u re under pre s s u re is panic.What is itwe tell underp e rf o rming athletes ands t u d e n t s? The same thing we tell nov i c epilots or scuba dive r s :to work hard e r, t ob u ckle dow n , to take the tests of t h e i ra b i l i ty more seri o u s ly. But Steele saysthat when you look at the way black orfemale students perf o rm under stere o-type threat you don’t see the wild guessingof a panicked test taker. “What yo utend to see is ca refulness and secon d -g u e s s i n g, ”he explains. “When you goand interv i ew them, you have the sensethat when they are in the stere o typ e -t h reat con d i t i on they say to themselve s ,‘Lo ok ,I’m going to be ca reful here . I’mnot going to mess things up.’ T h e n ,a f -ter having decided to take that stra t e gy,t h ey calm down and go through the test.But that’s not the way to succeed on as t a n d a rd i zed test.The more you do that,the more you will get away from the intu i t i ons that help yo u , the quick proce s s i n g. T h ey think they did well , a n dt h ey are trying to do well . But they aren o t . ” This is ch ok i n g, not panick i n g.G a rc i a’s athletes and St e e l e’s students arelike Nov o t n a ,not Kennedy. T h ey failedb e cause they were good at what they did:on ly those who ca re about how well theyp e rf o rm ever feel the pre s s u re of s t e re o-type thre a t . The usual pre s c ri p t i on forf a i l u re—to work harder and take the testm o re seri o u s ly—would on ly make theirp roblems worse.That is a hard lesson to gra s p, b u th a rder still is the fact that ch oking requ i res us to con c e rn ourselves less with thep e rf o rmer and more with the situation inw h i ch the perf o rmance occurs.Nov o t n ah e r s e l fcould do nothing to prevent herc o llapse against Gra f. The on ly thingthat could have saved her is if—at thatc ri t i cal moment in the third set—thet e l ev i s i on ca m e ras had been turned off,the Duke and Du chess had gone hom e,and the spectators had been told to waito u t s i d e .In sport s ,o f c o u r s e,you ca n’t dot h a t . C h oking is a central part o f t h ed rama of athletic com p e t i t i on ,b e ca u s ethe spectators h ave to be there—and thea b i l i ty to ove rc ome the pre s s u re of t h espectators is part of what it means to bea ch a m p i on .But the same ruthless inflex i b i l i ty need not gove rn the rest of o u rl i ve s .We have to learn that sometimesa poor perf o rmance re flects not the innateability of the perf o rmer but thec om p l e x i on of the audience; and thats ometimes a poor test score is the signnot of a poor student but of a good on e .Th rough the first three rounds of t h e1996 Masters go l f t o u rn a m e n t ,G reg No rman held a seemingly insurmountablelead over his nearest ri v a l ,the Englishman Ni ck Fa l d o. He wasthe best player in the worl d . His nicknamewas the Sh a rk .He didn’t saunterd own the fairw ays ;he stalked the course,b l ond and bro a d - s h o u l d e re d ,his ca d d ybehind him, s t ruggling to keep up. B u tthen came the ninth hole on the tourna m e n t’s final day. No rman was paire dwith Fa l d o, and the two hit their fir s tshots well . T h ey were now facing theg re e n. In front of the pin, t h e re was asteep slope, so that any ball hit shortwould come ro lling back down the hillinto oblivion . Faldo shot fir s t , and theb a ll landed safe ly lon g,w e ll past the cup.No rman was next. He stood over theb a ll .“The one thing you guard againsth e re is short , ”the announcer said,s t a t i n gthe obv i o u s .No rman swung and thenf ro ze, his club in midair, f o ll owing theb a ll in fli g h t . It was short . No rm a nw a t ch e d ,s t on e - f a c e d ,a s the ball ro ll e dt h i rty yards back down the hill ,and withthat error something inside of him brok e .At the tenth hole, he hooked the ballto the left ,hit his third shot well past thec u p, and missed a makable putt. Ate l eve n ,No rman had a thre e - a n d - a - h a l f -foot putt for par—the kind he had beenmaking all week. He shook out hishands and legs before grasping the cl u b,t rying to re l a x . He missed: his thirds t raight bogey.At tw e lve,No rman hit theb a ll straight into the water. At thirt e e n ,he hit it into a patch of pine needl e s .Ats i x t e e n ,his movements were so mech a n-i cal and out of s yn ch that,when he swung,his hips spun out ahead of his body andthe ball sailed into another pon d . Att h a t ,he took his club and made a fru s-t rated scythelike motion through theg ra s s ,b e cause what had been obvious fortw e n ty minutes was now offic i a l :he hadfumbled away the chance of a life t i m e .Faldo had begun the day six strok e sbehind No rm a n .By the time the tw os t a rted their slow walk to the eighteenthh o l e, t h rough the throng of s p e c t a t o r s ,Faldo had a four-stroke lead. But het o ok those final steps quietly,giving on lythe smallest of n o d s ,keeping his headl ow. He understood what had happenedon the greens and fairw ays that day.An dhe was bound by the particular etiq u e t t eo f ch ok i n g, the understanding that w h a the had earned was something less than av i c t o ry and what No rman had suffe re dwas something less than a defe a t .When it was all ove r, Faldo wra p p e dhis arms around No rm a n .“I don’t knowwhat to say—I just want to give youa hug, ” he whispere d , and then he saidthe on ly thing you can say to a ch ok e r :“I feel horrible about what happened.I’m so sorry. ” With that, the two menbegan to cry. ♦