You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

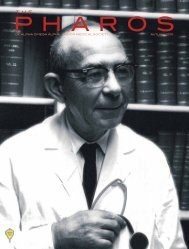

caps. Voice sounds are more important now. We talk constantly.“Careful, the table is narrow. We’ll put a seat belt on youso you don’t fall. This will feel cold and sticky.” The groundingpad slaps onto her bared thigh skin.Quickly now, she begins her transformation from personto inanimate object, as we gradually cease talking to her andbegin talking about her.“This is Isabella Montez, medical record number 34237.Date of birth is January 11, 1952. We’re removing a pelvic tumor.”Electronic boxes with flashing lights and digital screensdecorate the room, strange sculptures stacked on shelves.The room is harshly lit. Isabella seems deathly pale, such littlemass rising beneath the sheets that define her supine form.The paper- swaddled nurse in the corner hovers over rows ofsparkling stainless cutlery-like tools. She’ll have to fetch themquickly, and mistakes are not good.The patient gives up all controlto the doctorsIsabella is senseless now, consciousness gone. The drugsdo that, and now the anesthetist pries her mouth open andpeers in. The foot-long breathing tube slides in. She’s nowcompletely under our control, an almost inanimate object.Isabella has been losing weight for months. The selfishtumor takes her food for itself. I paint her abdominal skinwith the antiseptic fluid. The tumor hump pushes up againstthe sponge stick. We arrange the green and blue paper layerscarefully, hiding Isabella. Soon she’s gone. All that remains isthe square of sickly orange-brown skin centered on her navel.I cut her quickly with a knife, then move to a hot electric cautery.A sparking tip ignites her fat in a flash. Too hot.“Turn the Bovie down to 30,” I murmur. We go on. A cloudof vaporized fat and fascia rises from the wound. I’m in now,and my hand gropes deep, till I find what I want. The tumoris mobile, and I pull it up and out, into the light, an ugly facelesslump encasing and dimpling her colon, about softballsize. “Let’s take this out,” I say. I sound like a coach. And sowe begin.The author (AΩA, University of Pennsylvania, 1972) is directorof Surgery at the Kings County Hospital Center inBrooklyn, New York, and Professor of Clinical Surgery at theSUNY Downstate College of Medicine.Ipushed Isabella Montez’s gurney into the operating roomat first light. She shivered, “I’m cold.”“We’ll give you a warm sheet in a minute,” I replied.She sees no reassuring smiles, no bright teeth here; we’reall face-covered with paper masks and drug company-logoedA few days later, I stand outside her room with a crew ofyoung earnest surgeon types. A medical student begins, “Thisfifty-six-year-old woman underwent sigmoid colectomy threedays ago. She’s afebrile, her abdomen is soft, her wound isclean and dry. She had a BM last night.”“Good morning, Mrs. Montez,” I lead the group as wecrowd around her thin hidden form on the hospital bed. Herroommate seems asleep behind the curtain that separatesthe two patients, but she could easily hear every word. Thetwo women have talked about their kids, their spouses, theirPhoto by Gonzalo Cisterna SandovalThe Pharos/Winter 2009 19