Download The Pharos Winter 2011 Edition - Alpha Omega Alpha

Download The Pharos Winter 2011 Edition - Alpha Omega Alpha

Download The Pharos Winter 2011 Edition - Alpha Omega Alpha

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

���������������������������������������������<br />

� ����������� �<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> 2008 3

�Αξιος ��ωφελε�ιν το�υς ��αλγο�υντας<br />

����������������������<br />

�����������<br />

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

����������������������������������������������<br />

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

����������������������������������<br />

�����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

������������������������������������������<br />

������������������������<br />

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

�<br />

������������������������<br />

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������<br />

�<br />

���������������������<br />

���������������������������������������<br />

����������������������������������<br />

��������������������������������������������<br />

� �����������<br />

Officers and Directors at Large<br />

�����������������������<br />

���������<br />

������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

��������������<br />

�������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

������������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

����������������<br />

��������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

�����������������<br />

����������������<br />

��������������������<br />

���������������<br />

Medical Organization Director<br />

��������������������<br />

������������������������������<br />

Councilor Directors<br />

������������������������<br />

�<br />

����������������������������������<br />

�����������������<br />

���������������������������������<br />

����������������<br />

�<br />

��������������������������������<br />

Coordinator, Residency Initiatives<br />

�������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

Student Directors<br />

�������������<br />

��������������������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

����������������������������<br />

����������������<br />

�������������������������������<br />

������<br />

���������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

������������������<br />

����������������������<br />

������������������������������<br />

����������������������������<br />

�������������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

��������������������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

Editorial Board<br />

�������������������������<br />

������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

���������������<br />

�������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

������������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

�������������������������<br />

����������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

����������������<br />

������������������<br />

�����������������<br />

�����������������<br />

���������������������<br />

������������������<br />

����������������<br />

�����������������<br />

�������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

����������������������<br />

�����������������<br />

�������������<br />

������������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

����������������<br />

��������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

�������������<br />

�������������������������<br />

������������������<br />

������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

�������������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

������������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

�����������������<br />

��������������<br />

����������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

������������������<br />

������������������<br />

������������������<br />

������������������<br />

�������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

������������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

��������������������������<br />

����������������������<br />

��������������������<br />

��������������������������<br />

������<br />

��������������������<br />

��������������������������<br />

��������������<br />

��������������������<br />

������������������<br />

���������������<br />

�����������������������<br />

���<br />

������<br />

������<br />

��������������������<br />

���������������<br />

��������������������<br />

���������������������<br />

�<br />

���������������<br />

�<br />

�������������<br />

�������������������<br />

���������������<br />

�����������������<br />

����������������������������<br />

��������������<br />

��������������������

Editorial<br />

<strong>The</strong> song goes on<br />

Robert Atnip, MD<br />

<strong>The</strong> author (AΩA, University of Alabama, 1976)<br />

is a member of the board of directors of <strong>Alpha</strong><br />

<strong>Omega</strong> <strong>Alpha</strong>.<br />

am an academic vascular surgeon, a senior fac-<br />

I ulty member at a University Hospital, a mentor<br />

of medical students and residents, and a teacher<br />

of professionalism. My own lessons in professionalism<br />

came while in medical school, but<br />

not in any classroom or book. I don’t recall the<br />

word even being spoken during those four years<br />

(1974–78). No doubt some of those who modeled<br />

it for me were physicians, but in retrospect, the<br />

most influential person was no doctor, but a musician.<br />

That music has the power to pervade the human experience<br />

may be a mystery, but it is no secret. Music is as universal<br />

as the human senses, and as vital. As a form of human<br />

expression, music is at the same time both elemental and<br />

transcendent. It is one of humanity’s finest gifts to itself, a<br />

gift that to our lament cannot be as readily celebrated in <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Pharos</strong> as the visual and literary arts. Music is not for speaking<br />

or writing. Music is ineffable emotion, a sequence of nameless<br />

swells and surges that defy the bounds of speech. Our voices<br />

are put to much better use making music than describing it<br />

and, in like manner, professionalism is much less a creed to<br />

be discerned and codified than it is a craft to be realized and<br />

enacted. <strong>The</strong>rein lies the basis for choral music to instruct me<br />

in the finer points of professionalism.<br />

Nowadays, professionalism is a paramount concern to the<br />

health care world, but it was not always so. “Professionalism”<br />

was irrelevant to academia prior to 1965. My search for “professionalism”<br />

as a key word in OLD_OVID (1947–65) returned<br />

only the red-lettered retort, “Unable to match with any subject<br />

heading.” In the fifteen years that followed, “professionalism”<br />

made its debut with 180 appearances, the majority in nursing<br />

journals or, oddly enough, in the dentistry literature. But only<br />

in the last thirty years has “professionalism” gained enough<br />

traction to merit the eight subject headings to which it now<br />

maps in OVID, the thousands of publications devoted to<br />

probing its obliquities, or the several awards and grants now<br />

bestowed in its name by prestigious societies such as ours.<br />

This logarithmic progression is extraordinary for a concept<br />

that acquired its name as long ago as the fourteenth<br />

century. Toward the end of the so-called Dark Ages, the word<br />

“profess” appeared among religious orders with the meaning<br />

“to take a vow,” or “to declare [a belief] publicly.” This definition<br />

and related word forms served adequately, perhaps even<br />

admirably, throughout all subsequent ages of history and into<br />

modern times. Only in the post-Modern era has the simplicity<br />

and sparse eloquence of these phrases come to be viewed as<br />

inadequate for today’s professionals. But I think what may be<br />

lacking is not the words, but the . . . music!<br />

And so in the mid-1970s, modern professionalism’s “early<br />

years,” I came upon my unwitting mentor-to-be while in medical<br />

school in Birmingham, Alabama. Having enjoyed music<br />

and singing as a youth, and wanting some activity<br />

beyond the confines of studying anatomy<br />

and physiology, I met JWS, the organist and<br />

choirmaster at a local church. <strong>The</strong> meeting<br />

was happenstance, but serendipity has never<br />

worked any better magic than this. I joined and<br />

sang in his choir, as much an amateur singer as<br />

I was a fledgling doctor. But the experience was<br />

profound, a turning point for me, and a revelation<br />

of new worlds. For the next three years this<br />

choir became as important to me as my medical<br />

education. Under the direction of JWS, or more<br />

properly, under his spell, I learned what it is to<br />

“profess” choral music: to blend many voices into one sound,<br />

the music built on every voice, but ever greater than any one<br />

alone; to tune each voice and phrase toward perfection; to purify<br />

many harmonies into one great and coherent beauty. <strong>The</strong><br />

sounds and the music were exquisite, many of them recorded<br />

at that time, and still inspiring to me more than thirty years<br />

later. To listen to them is to understand the fruits of professionalism<br />

and, moreover, to discern therein a startling similarity<br />

to what we seek to do in the individual and corporate acts<br />

of medical practice.<br />

This connection of music to medicine may seem obscure to<br />

some, and self-evident to others. But I contend that the truths<br />

learned in the making of music are the same truths that we<br />

who profess medicine must teach our students, and re-affirm<br />

for ourselves: competence, discipline, determination, focus,<br />

artistry, the seeking of common goals, the drive to excel, the<br />

ability to lead and to follow, and one perhaps not as obvious:<br />

aesthetics—the presence of beauty and inner harmony in what<br />

we do. I do not equate humanism with professionalism, but<br />

they have much in common. <strong>The</strong>y are separate yet inseparable,<br />

linked by a common need for each to nourish the other. I was<br />

most fortunate at a remarkable and formative time of my life to<br />

be in a milieu suffused with an abundance of each. To those who<br />

cleared this path for me, I owe an inexpressible debt. <strong>The</strong>y knew<br />

that professionalism has not only a body, but a soul.<br />

It was never my destiny to become a professional musician,<br />

but I am delighted to be a musical professional. Music may not<br />

have made me a better medical scientist, but it has made me a<br />

better physician. Vita brevis, ars longa. To the extent that we<br />

are true to our identity as healers, then we must—in concert<br />

with advances in science and technology—remain centered on<br />

the collective humanity of patient and physician, which in all<br />

its forms is our common bond.<br />

JWS retired in 1998, and died in 2007 of Parkinson’s<br />

disease. He and Ted Harris were much alike. <strong>The</strong>y were extraordinary<br />

persons who led others to perform beyond expectations,<br />

and showed all those around them that exceptional<br />

effort yields uncommon rewards. <strong>The</strong>se two men were called<br />

into different professions, but each understood precisely what<br />

it meant to “take a vow.” and to “declare publicly.” It is to the<br />

betterment of humankind that each lived, and thus our own<br />

joyful duty to ensure that their song goes on.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 1

������<br />

����������<br />

������������<br />

�������� ��������������<br />

1 Editorial<br />

<strong>The</strong> song goes on<br />

Robert Atnip, MD<br />

35<br />

42<br />

46<br />

Health policy<br />

Our health care system is not<br />

broken—it’s obsolete!<br />

Jordan J. Cohen, MD<br />

<strong>The</strong> physician at the<br />

movies<br />

Peter E. Dans, MD<br />

Wall Street: Money Never<br />

Sleeps<br />

Conviction<br />

Reviews and reflections<br />

<strong>The</strong> Checklist Manifesto: How to<br />

Get Things Right<br />

Reviewed by David A. Bennahum,<br />

MD<br />

<strong>The</strong> Jump Artist<br />

Reviewed by Jeffrey L. Ponsky,<br />

MD<br />

Henry Kaplan and the Story of<br />

Hodgkin’s Disease<br />

Reviewed by William M. Rogoway,<br />

MD<br />

<strong>The</strong> National Institutes of Health:<br />

1991–2008<br />

Reviewed by Jack Coulehan, MD<br />

51 Letters<br />

AΩA NEWS<br />

38 2010 <strong>Alpha</strong> <strong>Omega</strong><br />

<strong>Alpha</strong> Robert J. Glaser<br />

Distinguished Teacher<br />

Awards<br />

52<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

National and chapter news<br />

Instructions for <strong>Pharos</strong> Authors<br />

Leaders in American Medicine<br />

������<br />

ARTICLES<br />

Visionary art?<br />

Shamans, Charles Bonnet, and the cave<br />

paintings<br />

Henry N. Claman, MD<br />

�<br />

Going first<br />

Susie Morris, MD, MA<br />

��<br />

<strong>The</strong> monsters of medicine<br />

Political violence and the physician<br />

Amanda J. Redig, MD, PhD<br />

��<br />

�������

�������<br />

Breaking bad news<br />

What poetry has to say about it<br />

Dean Gianakos, MD<br />

From rabbits to the<br />

League of Nations<br />

Early standardization of the insulin unit<br />

�������<br />

��<br />

Barry Fields, MD<br />

��<br />

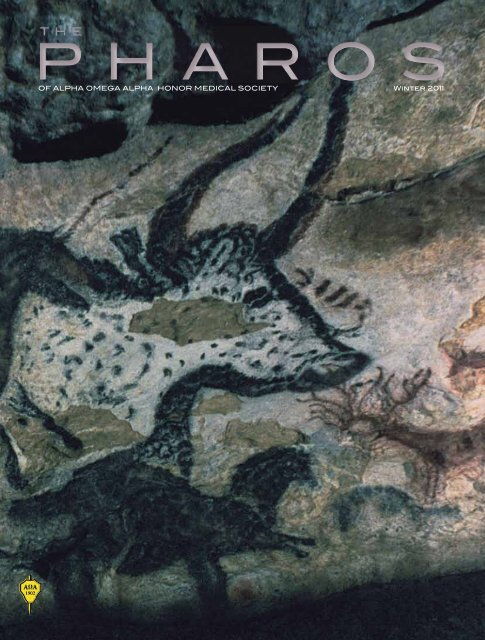

On the cover<br />

�����������������������<br />

See page 4<br />

���������� ������<br />

�������<br />

���������������������������������������������<br />

� ����������� �<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> 2008 3<br />

11 Room K461<br />

Mary Krane Derr<br />

15 Musings on an Attic<br />

Tetradrach<br />

Alvin J. Cummins, MD<br />

23 Sestina on Limb-<br />

Lengthening Surgery<br />

Jenna Le<br />

27 Heartache<br />

John Allan, MD<br />

34 <strong>The</strong> Defendant<br />

H. Harvey Gass, MD<br />

36 Memento Mori<br />

Michael R. Milano, MD<br />

37<br />

40<br />

POETRY<br />

Reading a Review<br />

H. J. Van Peenen, MD<br />

Winning Poems of the<br />

2010 Write a Poem for<br />

This Photo Contest<br />

Benevolent Instructions<br />

David R. Downs, MD<br />

Commencement<br />

David F. Dozier, Jr., MD<br />

Adolescent Choices<br />

H. J. Van Peenen, MD<br />

XX Ageless<br />

Thomas Atwater<br />

INSIDE<br />

BACK<br />

COVER

Visionary art?<br />

Shamans, Charles Bonnet, and the cave paintings<br />

Henry N. Claman, MD<br />

<strong>The</strong> author (AΩA, University of Colorado, 1979) is<br />

Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Associate Director<br />

of the Medical Humanities Program at the University of<br />

Colorado, Denver. He is a member of the editorial board of<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>.<br />

Paleolithic art, particularly the cave paintings of<br />

Southwestern Europe, is a source of amazement still.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se images haunt many of us, not only because of<br />

their beauty and their great age, (stretching back over 30,000<br />

years), but because they are one of the few entrées we might<br />

have into the lives of our ancestors, who are among the great<br />

masters of artistic creativity, and about whom we know very<br />

little apart from this art. <strong>The</strong> study of this art continues to<br />

expand as art historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, and<br />

natural history scientists try to unravel the mystery of what<br />

the art “means” and why it was made. <strong>The</strong>re is a wide divergence<br />

in opinions on this subject, and some experts have actually<br />

warned against further attempts to discover “the meaning”<br />

of paleolithic art. However, it is hard to abandon the quest,<br />

and this contribution attempts to call attention to another<br />

possible avenue of interpretation, relying on new neurophysiological<br />

concepts.<br />

<strong>The</strong> art was produced in profusion, and consists mainly<br />

of paintings and engravings, as well as sculpture in the round<br />

and in bas-relief. <strong>The</strong> early members of our genus and species,<br />

Homo sapiens sapiens, were hunter-gatherers. <strong>The</strong>y lived in<br />

small nomadic bands of perhaps fifty to one hundred people,<br />

in a mostly egalitarian society. <strong>The</strong>y made stone tools and had<br />

fire but made neither cloth nor pottery. Half of the art is in<br />

limestone caves and half is outside, mainly in shelters. Those<br />

in the caves are better preserved and have received the most<br />

attention.<br />

What was depicted? Many of the most prominent images<br />

are of animals, mainly large ones such as horses, bisons, bovids,<br />

lions, rhinoceri, reindeer, and so forth. Rarely seen is a<br />

small animal such as a rabbit or owl. <strong>The</strong> large animals are almost<br />

always shown in profile, in big or small images, complete<br />

or fragmentary. When I was lucky enough to be in the Great<br />

Hall of the “original” Lascaux cave (now closed to the public)<br />

I felt that I was engulfed in the midst of a huge stampede. It<br />

was an overwhelming experience of power and speed. In addition<br />

to all the animal depictions, however, there are a lesser<br />

number of human figures, or parts of humans, including positive<br />

and negative hand prints and images of (mainly female)<br />

genitalia. Intact humans are rare and almost always masked.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a also very large number of enigmatic forms that are<br />

Man looking at prehistoric cave painting of animals.<br />

Photo by Ralph Morse//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 5

Visionary art?<br />

Bulls, horses, deer, Lascaux Cave, France, about 17,000 years ago.<br />

© <strong>The</strong> Bridgeman Art Library/Getty Images, Inc.<br />

difficult to describe, called abstract symbols, or designs, and<br />

so forth. <strong>The</strong>se range from simple colored dots or strokes or<br />

carved shallow cupules in the stone to complex grid-like paintings<br />

or engravings. Some of these geometric designs have been<br />

termed “tectiforms” (roof-like) although there is no evidence<br />

that there were any roofs.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se abstract forms, because of their refusal to give up<br />

their secrets, have been rather neglected by historians, at least<br />

in comparison with the more flamboyant animal images, to<br />

say nothing about the carved and decorative mostly female<br />

statuettes (misnamed “Venus” figurines). <strong>The</strong>se abstract images<br />

can give us additional clues as to the production of the<br />

art in general.<br />

Deciphering the “meanings” of paleolithic art<br />

Analyzing the art is a formidable task, and the process continues,<br />

with various schema current at one time or another. 1,2<br />

Art for art’s sake—During the period when paleolithic art<br />

was known mainly from small carved and engraved bones and<br />

antlers, the genre was regarded as aesthetic and playful. This<br />

approach has been largely abandoned.<br />

Sympathetic magic—When the great cave paintings of<br />

Altamira and Lascaux were discovered, the depiction of large<br />

hunted animals, often with spears or arrows in them, led<br />

to the concept of “hunting magic” or “sympathetic magic.”<br />

According to this model, emphasized by Sir James Frazer in<br />

<strong>The</strong> Golden Bough, hunter-gatherer people made pictures of<br />

their prey to remember yesterday’s foray or to imagine and<br />

ensure the success of tomorrow’s venture. 3 This interpretation<br />

has its advocates today.<br />

In the structuralist approach, pioneered by André Leroi-<br />

Gourhan, the images were subjected to sophisticated measuring<br />

and counting techniques that led to interpretations of the<br />

arrangement of art in symbolic terms, emphasizing quantitative<br />

correspondences and dualistic contrasts, e.g., male versus<br />

female symbols, red versus black images and horses versus<br />

bison. 4 <strong>The</strong> ultimate rationale may have been to promote fertility<br />

in both human and animal worlds, which were, of course,<br />

extremely interwoven and interdependent in hunter-gatherer<br />

societies. Many find this approach arcane.<br />

6 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

Emphasis currently centers on what has been called the<br />

mystico/religious interpretation, in which spiritual concepts<br />

are invoked and shamans are considered to be closely involved<br />

in art production and corresponding ritual activities. This approach<br />

is largely influenced by David Lewis-Williams and his<br />

studies of the rock art of the San People of South Africa. He<br />

applies this interpretation to paleolithic and neolithic art. 5,6<br />

R. Dale Guthrie dismisses this concept in favor of a natural<br />

history/evolutionary schema, placing the art in the larger context<br />

of environmental influences and linking artistic behavior<br />

to our evolutionary past. 2<br />

None of these approaches has unanimous scholarly approval.<br />

Indeed, experts are beginning to doubt that we will<br />

ever uncover “the meanings.” Yet the desire to do so is irresistible,<br />

and so let us turn to a particular image.<br />

<strong>The</strong> shaman of Lascaux<br />

This astonishing figure, discovered when the cave itself<br />

was opened in 1940, should have brought the idea of shamans<br />

to the fore right away. It is unique, being the only complete<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Shaman of Lascaux,” about 17,000 years ago. A bird-headed and -handed ithyphallic stick man in front of a wounded bison,<br />

pierced by spears, with entrails spilling out. <strong>The</strong> Shaman has a bird-head staff. © Charles and Josette Lenars/CORBIS.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 7

Visionary art?<br />

Abstract “designs” (with perhaps a positive handprint)—a montage of items from caves in what is now France and Northern Spain, about<br />

17,000–10,000 years ago. Illustration by Jim M’Guinness.<br />

human image in the cave. It is far from the stampede of animals<br />

I mentioned above, and is placed on the wall at the bottom<br />

of an eighteen-foot “well” or “shaft”—curiously isolated<br />

and difficult to access. Considering the general profusion of<br />

animals on the walls and even the ceilings, the shaman is solitary<br />

and secluded. This stick-figure of a man, drawn poorly in<br />

outline, has a bird’s head and bird’s hands, with a bird-headed<br />

scepter at his side. He is obviously male, with a prominent<br />

erect penis (the “ithyphallic position”)—a symbol of power.<br />

He is either upright or leaning, depending on the angle of the<br />

photograph. He is next to a well-drawn bison that is looking<br />

over its shoulder at a gaping wound in his flank with his intestines<br />

falling out. <strong>The</strong>re are two spears in his side.<br />

I agree with Joseph Campbell that he is a shaman, part<br />

human, part bird. 7 Including the bison, the ensemble must<br />

be the oldest narrative visual scene in human history. Yet it<br />

is profoundly ambiguous. What is the story? What is the shaman’s<br />

role vis-à-vis the bison?—a healer?—a hunter? Is he in a<br />

trance? Is he drugged? Why is he ithyphallic?<br />

Nevertheless, he is not the only masked magic man in the<br />

caves. <strong>The</strong>re is the masked and antlered “sorcerer” man in the<br />

Trois Freres cave, and others as well.<br />

8 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

<strong>The</strong> abstract designs—providing clues?<br />

Returning to the abstract images, it is understandable<br />

that they have received less attention<br />

than those of animals and people. <strong>The</strong>y are very<br />

numerous, but are often small and have proved<br />

opaque to interpretation. Perhaps the most attentive<br />

scholar has been S. Giedion, the Swiss<br />

historian. He believed that “symbolization is the<br />

key to all paleolithic art,” 8p79 and he points out<br />

that the “great abstract symbols which have no<br />

counterpart in the world of reality” are often<br />

“hidden away in the most inaccessible parts of the<br />

caverns.” 8p241 While the meanings of female pubic<br />

triangles and vulvas as well as penile images are<br />

easy to understand in terms of fertility and procreative<br />

symbolism, this is not true of the abstract<br />

designs. What then?<br />

Lewis-Williams thinks they are hallucinations,<br />

conjured up by shamans in trances, which<br />

provided powerful spiritual experiences of the<br />

San People’s three-tiered cosmos, and which<br />

were later displayed as rock art—petrographs and<br />

petroglyphs. 5 This is a concept worth considering.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hallucination approach<br />

This is a complicated subject indeed. <strong>The</strong><br />

very long list of conditions associated with visual<br />

hallucinations includes ocular disorders, CNS<br />

disorders, toxic disturbances, psychiatric illnesses,<br />

and “normal” persons. 9 In the context of<br />

images hidden in large, dark caves, it is of interest<br />

that a number of the hallucinogenic scenarios<br />

in “normal” persons involve forms of sensory<br />

deprivations. <strong>The</strong>se include dreams, hypnagogic<br />

and hypnotic states, sleep deprivation, and simply<br />

blindfolding. To this list should now be added a<br />

relatively new syndrome.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Charles Bonnet Syndrome<br />

This condition has a curious history. 10 Bonnet,<br />

born in 1720, was a Swiss/French naturalist and<br />

philosopher. (He deserves more recognition for<br />

his experiments in wood lice, establishing the phenomenon<br />

of parthenogenesis.) In 1760 he wrote a book in which he<br />

described how his eighty-seven-year-old grandfather lost his<br />

vision to cataracts and developed hallucinations “of men, of<br />

women, of birds, of carriages, of buildings.” Interestingly, the<br />

same later happened to Bonnet himself.<br />

<strong>The</strong> situation lay fallow until 1967 when George de Morsier<br />

proposed the term Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS) to describe<br />

the presence of recurrent visual hallucinations generally<br />

in persons with impaired vision but without clouded<br />

sensoria. Such persons are often elderly. Since then, the<br />

syndrome has been increasingly recognized and studied. 11 It<br />

is present in perhaps ten percent of the elderly with impaired<br />

vision.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hallucinations experienced are varied and often complex,<br />

in contrast to “unformed” hallucinations such as spots<br />

and flashes of light, which are termed “phosgenes.” <strong>The</strong>y include<br />

animals, humans, geometric figures, and designs, similar<br />

to what is seen in the caves. <strong>The</strong>y are in color or black and<br />

white, and are often brilliant and clear, contrasting with the<br />

poor “regular” vision of the subjects. <strong>The</strong>y frequently fade or<br />

disappear as sight deteriorates further. <strong>The</strong> commonest cause<br />

of CBS in our society is age-related macular degeneration,<br />

but it has been reported in the young and also in association<br />

with pathological changes from the eye to the visual cortex.<br />

To diagnose CBS, there should be no evidence of delirium,<br />

dementia, psychosis, or intoxication. <strong>The</strong> visions are not felt<br />

to originate in the eye itself. 11<br />

It is well-known that hallucinations with a normal sensorium<br />

may be provoked or aggravated by a number of factors<br />

including sensory deprivation, the hypnagogic state, physical<br />

or auditory stimuli, extreme pain, etc. 9 <strong>The</strong> same is true of<br />

CBS.<br />

<strong>The</strong> pathophysiology of CBS—the release<br />

phenomenon<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea that hallucinations may be caused by “irritative”<br />

foci in the brain derives by analogy from John Hughlings<br />

Jackson’s analysis of focal epilepsy. This explanation for hallucinations<br />

has generally given way more recently to the<br />

work of David Cogan 12 (who also refers to Louis J. West 13 )<br />

that suggests that hallucinations of various types are instead<br />

“release phenomena.” Interestingly, this concept also derives<br />

from Hughlings Jackson, who developed the general concept<br />

that higher functional layers of the CNS normally inhibit<br />

lower layers. When, however, the higher layers are themselves<br />

impaired, normally suppressed activities of the lower layers<br />

are released. (Consider the spasticity of the pithed frog or<br />

alcohol-induced misbehavior.) In the visual system, normal afferent<br />

stimuli dampen or block the spontaneous “endovision”<br />

activities. But when, in some people, blindness “deafferents”<br />

the visual pathways, the spontaneous endovisual activities take<br />

over, leading to hallucinations. In fact, fMRI studies support<br />

this concept. 14<br />

Hallucination manifestations<br />

Many studies of hallucination point out similarities in the<br />

images that are seemingly independent of the cause and the<br />

culture involved. Heinrich Klüver, with an extensive experience<br />

primarily associated with mescal studies, wrote of three<br />

stages of evolving hallucinations 15 :<br />

Type I—“Form constants,” namely geometric abstract designs<br />

described as gratings, lattices, fretwork; also tunnels,<br />

alleys, vessels; and spirals.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 9

Visionary art?<br />

Type II—Familiar objects such as people, faces, animals,<br />

landscapes.<br />

Type III—Fabulous landscapes and monstrous forms.<br />

Hallucinations in paleolithic art?<br />

<strong>The</strong> above outline of selected aspects of paleolithic imagery<br />

suggests that the abstract designs may not in fact be symbols.<br />

In fact, it was never clear what they might have symbolized.<br />

Instead they may be graphic representations of visual hallucinations—the<br />

“form constants” of Klüver’s Stage I.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are a number of circumstances that support this<br />

hypothesis, circumstances that reinforce each other:<br />

1. Many of the paintings and engravings are made in very<br />

deep caves, where the darkness (and difficulty of access) is<br />

daunting. <strong>The</strong>ir very locations, even if dimly illuminated by<br />

the uncertain flickerings of oil lamps and flambeaux, would<br />

have been situations of considerable sensory deprivation.<br />

2. Any degree of partial visual impairment—from disease,<br />

CBS, trauma, etc.—would only heighten the deprivation.<br />

3. <strong>The</strong> possible (if not probable) use of psychedelic substances<br />

in trances or ceremonies would further the tendency<br />

to hallucinate. (What indeed was going on with the shaman<br />

of Lascaux?)<br />

4. <strong>The</strong> role of dreaming in gaining access to mental imagery<br />

should not be discounted.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Does the “hallucination approach” to the abstract designs<br />

give us any insight into the most intriguing problem of<br />

paleolithic art—the “meaning(s)” of the animal portrayals?<br />

Certainly, in a hunt-oriented culture dependent on animal<br />

protein for sustenance and perhaps also on animal skins for<br />

protection and disguise, it is not surprising to see those images.<br />

But it is not so simple. We are not seeing the mere paleolithic<br />

dinner menu, as many of the animal species portrayed<br />

were too dangerous to hunt and were, to judge from bony<br />

remains, not eaten. Nonetheless, the images of these animals<br />

demonstrate power, when one considers their numbers, their<br />

sizes, their detailed and imaginative depictions, their often<br />

secluded locations, and their artistic skill. <strong>The</strong> purposes were<br />

probably multiple, including messages such as “come here<br />

and nourish us” as well as “stay away—you’re dangerous” (the<br />

apotropaic or “warding off evil” strategy).<br />

<strong>The</strong> shaman of Lascaux confronting the wounded bison<br />

(risking being wounded himself in the process) would seem<br />

to provide a conceptual and possibly material link between<br />

the human/animal world and the realm of the spirits. It would<br />

be he who, via his trances (however induced), experienced<br />

that spiritual world and then “returned” to inspire the artists,<br />

perhaps including himself. In this context, these extraordinary<br />

portraits would reflect not only actual animals but thoughts,<br />

wishes, memories, or dreams or Type II Klüver hallucinations<br />

of them as well.<br />

E. H. Gombrich, the outstanding art historian, remarked<br />

that “the further back we go in history . . . the less sharp is<br />

the distinction between images and real things; in primitive<br />

societies, the thing and its image were simply two different . . .<br />

manifestations of the same energy or spirit.” 16p155<br />

Perhaps these artists perceived no differences at all!<br />

References<br />

1. Bahn PG, Vertut J. Journey Through the Ice Age. Berkeley<br />

(CA): University of California Press; 1997.<br />

2. Guthrie RD. <strong>The</strong> Nature of Paleolithic Art. Chicago: University<br />

of Chicago Press; 2005.<br />

3. Frazer JG. <strong>The</strong> Golden Bough: <strong>The</strong> Roots of Religion and<br />

Folklore. New York: Avenel Books; 1981.<br />

4. Leroi-Gourhan A. <strong>The</strong> Dawn of European Art: An Introduction<br />

to Palaeolithic Cave Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University<br />

Press; 1982.<br />

5. Lewis-Williams D. <strong>The</strong> Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and<br />

the Origins of Art. London: Thames and Hudson; 2002.<br />

6. Clottes J, Lewis-Williams D. <strong>The</strong> Shamans of Prehistory:<br />

Trance and Magic in the Painted Caves. New York: Harry N.<br />

Abrams; 1998.<br />

7. Campbell J. <strong>The</strong> Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. New<br />

York: Penguin Books; 1976: 300–302.<br />

8. Giedion S. <strong>The</strong> Eternal Present: A Contribution on Constancy<br />

and Change. New York: Bollingen Foundation; 1962.<br />

9. Cummings JL, Mega MS. Chapter 13: Hallucinations. In:<br />

Cummings JL, Mega MS. Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience.<br />

Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003: 187–99.<br />

10. Hedges TR Jr. Charles Bonnet, his life, and his syndrome.<br />

Surv Ophthalmol 2007; 52: 111–14.<br />

11. Menon GJ, Rahman I, Menon SJ, et al. Complex visual hallucinations<br />

in the visually impaired: <strong>The</strong> Charles Bonnet Syndrome.<br />

Surv Ophthalmol 2003; 48: 58–72.<br />

12. Cogan DG. Visual hallucinations as release phenomena. Albrecht<br />

v Graefes Arch klin exp Ophthal 1973; 188: 139–50.<br />

13. West LJ. Chapter 9: A Clinical and <strong>The</strong>oretical Overview of<br />

Hallucinatory Phenomena. In: Siegel RK, West LJ, editors. Hallucinations:<br />

Behavior, Experience, and <strong>The</strong>ory. New York: John Wiley &<br />

Sons; 1975: 287–311.<br />

14. ffytche DH, Howard RJ, Brammer MJ, et al. <strong>The</strong> anatomy<br />

of conscious vision: an fMRI study of visual hallucinations. Nature<br />

Neurosci 1988; 1: 738–42.<br />

15. Klüver H. Mescal and Mechanisms of Hallucinations. Chicago:<br />

University of Chicago Press; 1966.<br />

16. Sontag S. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and<br />

Giroux; 1977.<br />

<strong>The</strong> author’s address is:<br />

Allergy/Immunology B164 RC2<br />

12700 E. 19th Avenue, Room 10100<br />

Aurora, Colorado 80045<br />

E-mail: henry.claman@ucdenver.edu<br />

10 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

R O O M<br />

For Adrian Felix Carroll<br />

Tiny blue open-backed gown<br />

that never quite ties back up.<br />

Tiny blood pressure cuff,<br />

thermometer cuff.<br />

Tiny vital signs.<br />

Tiny primary color-coded IVs,<br />

tiny calibrated pumpings<br />

of opiate, anxiolytic, total<br />

parenteral nutrition with adjusted<br />

lipids to avert liver failure.<br />

Tiny blood transfusion.<br />

Tiny ostomy bag.<br />

Tiny liquid rolling crescents<br />

of bluegreen wake-eye. Tiny<br />

flickering visits with.<br />

Tiny answers<br />

from hall-snagged docs.<br />

So what is there here<br />

to miniaturize away<br />

this innards-clawing, hemorrhagic<br />

fever of grief?<br />

Mary Krane Derr<br />

Mary Krane Derr is a poet, writer, musician,<br />

chronic disease patient, and fourth-generation<br />

South Side Chicagoan. Her address is: 6105 South<br />

Woodlawn #3S. Chicago, Illinois 60637. E-mail:<br />

marykderr@aol.com.<br />

Illustration by Jim M’Guinness<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 11

���������<br />

Susie Morris, MD, MA<br />

<strong>The</strong> author is a resident in Psychiatry<br />

at the University of Southern<br />

California. This essay won honorable<br />

mention in the 2010 <strong>Alpha</strong> <strong>Omega</strong><br />

<strong>Alpha</strong> Helen H. Glaser Student Essay<br />

Competition.<br />

She has it so easy.<br />

I guess this shouldn’t be the<br />

first thing that comes to mind<br />

when I look at her. It’s about 12:30 in<br />

the afternoon. She is supine, dare I say<br />

resting? I feel uncomfortable calling<br />

her comfortable because I wonder if<br />

she’s already dead. I wonder if she died<br />

yesterday after she stopped speaking to<br />

us. I peel her eyelids back, and they are<br />

dilated. But she is propped here nonetheless,<br />

her heart still beating faintly<br />

through layers of fat under my stethoscope.<br />

At this point, it’s a stupid ritual.<br />

Her brother and niece are here looking<br />

on.<br />

“Kat went home for a shower,” her<br />

brother tells me. “Dr. Li talked her into<br />

it this morning. He needed to remind<br />

her it was okay to take care of herself.”<br />

Kat is Jenn’s partner. I can’t tell you<br />

how many lesbians I’ve known who<br />

went by Kat or Jenn. As her brother<br />

says her name, I wonder if she was a<br />

Katie or Kathy growing up and then<br />

switched to Kat later in life because it<br />

meshed better with her butch identity.<br />

I met the two of them four days ago.<br />

I found them, Jenn and Kat, sitting in<br />

this hospital room with a broad view<br />

of the city. Kat was perched anxiously<br />

on the fold-out couch, and Jenn was<br />

reclined confidently in the armchair<br />

next to her hospital bed, fully clothed in<br />

a short-sleeved button down and denim<br />

shorts. Both women had short unmistakably<br />

gay hair—the same haircut I<br />

once attempted during college when I<br />

was trying on my own identity. I was<br />

immediately drawn to them because<br />

something about them reminded me<br />

of home.<br />

Jenn told me that she’d been having<br />

hip pain, deep in her left side. She<br />

pointed to the region, and Kat watched<br />

her with cat-like eyes as if to make sure<br />

she described it in its full detail. Jenn<br />

starts a sentence with a slow, casual<br />

voice, one of those just-because-I-can<br />

smiles on her face. Kat finishes those<br />

sentences sharply with full medical detail,<br />

leaning forward into my face closer<br />

and closer each time.<br />

“I guess it started on like Friday, I<br />

think,” Jenn says, kind of looking out at<br />

the cityscape through the window.<br />

“Yes, it was Friday,” Kat states with<br />

some urgency.<br />

No fevers, no bowel symptoms, urinary<br />

symptoms, nothing. Just the pain.<br />

“And Kat says she saw a lymph node<br />

or something. That right, hon?”<br />

“Yes, she has a swollen inguinal<br />

lymph node. I first felt it on Friday, too,<br />

when she was in the shower.” Kat’s face<br />

is wrinkled now, with worry. Her eyes<br />

are dry but red and irritated. She uses<br />

the word “inguinal” to warn me that she<br />

too is medical.<br />

Jenn and Kat are nurses, home health<br />

nurses. This is actually how they met.<br />

“She was the leader of our team,”<br />

Kat tells me later with fresh pride as if<br />

it were yesterday, when in reality, Jenn’s<br />

illness has prevented her from working<br />

for months now.<br />

I think about this: the two of them<br />

making house visits together, surrounded<br />

by the death and sickness<br />

that provided the backdrop for their<br />

romance. Kat was smiling during the<br />

retelling, and her face was transparent<br />

with the old thrill of seducing her<br />

former boss. This was twelve years ago<br />

now. Four years ago, Jenn became suspiciously<br />

swollen. She was diagnosed with<br />

ovarian cancer. <strong>The</strong> intervening years<br />

are notable now for one large reductive<br />

surgery, the loss of Jenn’s uterus,<br />

ovaries, and omentum, and half a dozen<br />

chemotherapy trials. I pulled up her latest<br />

PET scan, and stable mets glowed<br />

back at me, a reminder that the chemotherapy<br />

had only delayed the inevitable<br />

for now. Luckily, she had remained<br />

physically quite strong and was looking<br />

forward to starting a new chemo regimen<br />

next week.<br />

It was Kat who kept her so fit. She<br />

administered meticulous, gentle care<br />

round the clock, but the past six months<br />

had proven increasingly difficult as Jenn<br />

suffered from intractable abdominal<br />

pain and several admissions for small<br />

bowel obstructions. Kat knew the landscape<br />

of Jenn’s body better than Jenn<br />

ever had. This is what one would expect<br />

of lovers of twelve years, except Kat’s<br />

knowledge was borne of something different.<br />

Kat’s eyes now combed the body<br />

of her life partner seeking suspicious<br />

changes, marks that portended the future,<br />

rather than pleasured in the right<br />

12 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

now. <strong>The</strong> numbers in her last CBC, her<br />

last bowel movement, its consistency,<br />

the color and volume of her urine. It was<br />

terror that prompted her daily searches<br />

and created, for them, a new connection<br />

between their bodies, a novel sort<br />

of lovemaking.<br />

It reminded me of years earlier when<br />

I totaled my car. My partner’s mother<br />

had sent us on our way that rainy morning.<br />

We called her later that day from<br />

the interstate, my car in pieces, to tell<br />

her what happened. She told me later<br />

that every time one of her girls left<br />

home, she always imagined the worst,<br />

thinking that if she thought of it first,<br />

it would never happen. That day, it<br />

seemed her pre-emptive imaginings<br />

had betrayed her. I wonder if Kat’s<br />

relentless surveying and bargaining<br />

came out of the same hope.<br />

“It was here-ish,” Kat said, her<br />

fingers plunged into Jenn’s groin,<br />

her gray pubic hair exposed while<br />

my resident and I stood by. Jenn<br />

was half listening, half aware of the<br />

low buzz of All My Children coming<br />

from the flat screen. “For some reason,<br />

I guess I can’t feel it now,” she said, bewildered<br />

and frustrated.<br />

“I never felt anything,” Jenn laughed.<br />

Kat scowled at the floor, seemingly pondering<br />

how her own fingers had somehow<br />

deceived her.<br />

I couldn’t feel anything either.<br />

Neither could my resident. At Kat’s urging<br />

though, in addition to increasing<br />

Jenn’s pain meds, we agreed to get some<br />

lab work and an abdominal CT.<br />

Kat and Jenn had spent the past<br />

two years or so preparing for the final<br />

moments. On the palliative service, I’d<br />

found this was actually kind of rare.<br />

Most people would delay and delay,<br />

throwing radioactivity and chemicals<br />

at tumors that laughed at their efforts,<br />

growing into organs and bone, hiding<br />

from x-rays and stealing moms away<br />

from babies, babies away from moms,<br />

lovers from lovers. Kat and Jenn, in addition<br />

to pursuing aggressive curative<br />

therapies, sought comfort in psychotherapy<br />

where they spoke freely about<br />

what was to come, what Jenn wanted it<br />

to look like, when and under what circumstances<br />

she wanted to stop.<br />

“Well, I’ve had four years since I was<br />

diagnosed.” Jenn is very frank with her<br />

words. “You know, I’d love four more.<br />

Shit, I’d like forty more, but we’re prepared<br />

either way.” I believed that Jenn<br />

was. Kat was another story. Kat’s movements<br />

were like Jenn’s words, decisive<br />

and exact. Wiping sweat from Jenn’s<br />

forehead, combing her hair from her<br />

face, positioning her arms about her<br />

body. However, sometimes I caught her,<br />

in between stoic statements, staring<br />

down at the floor like someone does<br />

whose eyes just flooded, waiting for the<br />

water to resorb, and then looking back<br />

up into the conversation.<br />

We really thought her pain sounded<br />

like a pulled muscle or something.<br />

Something really mild. She was pooping<br />

and peeing and without other systemic<br />

signs of something going wrong.<br />

Perhaps her pain was just related to<br />

her being almost sixty and overweight.<br />

Perhaps it had nothing to do with her<br />

cancer at all. It appeared to be a false<br />

alarm, and I figured we’d have her back<br />

home in no time. As I talked out my differential<br />

with the two of them, Kat nodded<br />

with some degree of relief, albeit<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 13

Going first<br />

About the author<br />

I was born and raised<br />

in rural Utah. I attended<br />

Smith College and graduated<br />

with a degree in<br />

philosophy in 2004. I<br />

am a recent graduate<br />

of Northwestern<br />

University Feinberg School of<br />

Medicine where I earned my<br />

MD and my Masters in Medical<br />

Humanities and Bioethics. I am<br />

starting my residency in psychiatry<br />

this year at the University of<br />

Southern California. I hope to pursue<br />

a career in geriatric psychiatry.<br />

guarded. She accepted my explanation<br />

but called the family anyway.<br />

Jenn reminded me again: “Kat is my<br />

power of attorney.”<br />

“Yes, of course.” I was relieved they’d<br />

done the paperwork, aware of all the<br />

hospital horror stories that had befallen<br />

other gay couples, thinking also that<br />

it was premature to be worrying who<br />

would make decisions for her if she<br />

couldn’t do so herself. She looked just as<br />

healthy as I did.<br />

Radiology paged my attending the<br />

following afternoon. I pulled up Jenn’s<br />

CT. She had an abscess in her back muscle,<br />

on the left, just where her pain had<br />

originated. It was large enough for a med<br />

student to see it, meaning it was pretty<br />

damn big. It was a pillowed pocket of<br />

air and fluid, indicating either active<br />

bacteria or a fistula between her bowel<br />

and back or both. Either way, the recommendation<br />

was to stick a drain in it. I<br />

remember being surprised although not<br />

alarmed. We’d stick a central line in her<br />

neck and send her home with IV antibiotics<br />

and a drain coming out of her side.<br />

She continued to appear very well—<br />

moving around her room, her pain<br />

under better control. I was shocked<br />

to see an elevated white count on her<br />

CBC. She didn’t look sick! I scheduled<br />

her with interventional radiology the<br />

following afternoon. <strong>The</strong> drain was<br />

placed without incident. That evening,<br />

I dropped by her room to say hello.<br />

She and Kat had visitors: Jenn’s sisters,<br />

brother, and niece. Jenn seemed jovial.<br />

Kat appeared more at ease than before.<br />

She even smiled when I told her goodnight.<br />

“See you tomorrow,” Jenn said. Her<br />

sister hugged me. “See you tomorrow,<br />

girlfriend,” she said.<br />

Before heading to her room the next<br />

morning, I pulled her vitals up on the<br />

computer. Her heart rate was up, all<br />

night, into the hundreds. Her most recent<br />

blood pressure read 90/60: alarmingly<br />

low. Topped with a fever of 102<br />

degrees. All signs pointed to sepsis. I<br />

could feel my own heart bump around<br />

in my chest. I could feel my fingertips<br />

and groin get numb with the anxiety of<br />

heavy failure. How could I have not seen<br />

this coming?<br />

I waited for my attending before I<br />

went to the room. I was afraid of the<br />

picture that the vitals had painted for<br />

me, and I knew that if I actually looked<br />

at her, that would only make it real. I<br />

wasn’t ready to hit that on my own.<br />

“It appears that Jenn is septic,” my<br />

attending explained to the family. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

didn’t know sepsis from a septic tank,<br />

none of them medical. But the connection<br />

between the two seemingly related<br />

entities conjured a fitting image of severity.<br />

I could see that. Kat knew best<br />

though, herself a nurse. <strong>The</strong> word softened<br />

her voice and cut deep lines in her<br />

weary face. She looked ruddy, almost<br />

hungover with sadness this morning.<br />

She knew it all along. She had been<br />

guarded, accepting our explanations and<br />

speculations throughout the admission.<br />

Carefully optimistic, but knew to call<br />

the family anyway.<br />

Looking at Jenn: she knew too. It<br />

wasn’t the pain that brought her in, I<br />

decided, looking back at it from where<br />

I was in time now. <strong>The</strong> pain had been a<br />

sign, and she knew.<br />

We asked the regular questions.<br />

“What’s your understanding of what’s<br />

going on, Jenn?” That’s my attending’s<br />

gentle voice, priming them for the<br />

events looming on the horizon.<br />

“Well, it looks like I may die.” Her<br />

frankness was killing me. I had to swallow<br />

hard and look away from her. Kat<br />

took her hand and moved to sit on her<br />

bed. She couldn’t get close enough to<br />

her. I remember feeling that way as a<br />

child, small spooning my mom in my<br />

parent’s bed at night, thinking that if I<br />

could just get closer and closer, I would<br />

be invincible. This is how Kat looked<br />

at Jenn now—like if she could just get<br />

close enough, maybe she could keep her,<br />

get away from the bad-news voices, and<br />

be invincible.<br />

Jenn was weak, intermittently trailing<br />

off, but lucid when she needed to<br />

be. In between cracking jokes about<br />

the doom in the room, she made her<br />

intentions very clear, careful always to<br />

speak in the first person, plural. Now,<br />

she was speaking for Kat, too. Jenn may<br />

have been dying, but it seemed Kat was<br />

surrendering. She asked us to stop the<br />

antibiotics.<br />

“I’m at peace, you know,” she huffed,<br />

showing her exhaustion. “Everyone is<br />

here. Kat’s here.”<br />

“She keeps twitching,” Kat said,<br />

watching Jenn’s legs worm around under<br />

the sheets.<br />

“Oh, that doesn’t bother me,” Jenn<br />

said.<br />

We ignored Jenn and started something<br />

to stop the twitching. Our focus<br />

had shifted from treating Jenn to protecting<br />

Kat. If Kat didn’t want to see<br />

twitching, then we would make it so.<br />

That was the one thing we could do for<br />

her. It made me feel a little more useful<br />

in my attempts to make up for the colossal<br />

failure I’d suffered against the natural<br />

forces that were claiming Jenn.<br />

Jenn didn’t really speak again after<br />

that. She fell into a kind of trance,<br />

sometimes restless. At those times, we<br />

gave her morphine, and she was quieted<br />

again. Her breathing was rough.<br />

We patched her with scopolamine and<br />

fentanyl.<br />

14 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

Kat claimed that she and the family<br />

were working shifts. This was a lie. <strong>The</strong><br />

family wandered in and out through<br />

the day. Kat went nowhere, sitting on<br />

the bed, feeling Jenn’s skin, placing ice<br />

packs, requesting acetaminophen suppositories<br />

to bring down Jenn’s fever.<br />

My resident told her this morning<br />

to go home for a while, get a shower, a<br />

change of clothes. Eat something. “Don’t<br />

feel guilty,” he’d told her. And she left.<br />

During her absence, I thought I’d<br />

take a break, too. Jenn was clinging to<br />

the status quo. I thought she’d make it<br />

through the weekend. I went to the cafeteria<br />

to get a soda. My pager went off<br />

about that time.<br />

Jenn’s brother and niece were sitting<br />

next to the bed. <strong>The</strong> television was off,<br />

the sun beat down on the window. It<br />

made me think it was warm outside<br />

when really, it was just a cool 60 degrees<br />

with some incidental sunlight here and<br />

there. Jenn’s face was grey, her hands<br />

still warm. I placed my stethoscope<br />

over her chest and watched the clock.<br />

<strong>The</strong> silence in her chest was eerie. <strong>The</strong><br />

Owl, symbol of Athens, reverse of<br />

a silver tetradrachm from Athens. © Corbis.<br />

sixty seconds were long and made me<br />

very aware of the pain in my back from<br />

bending over. Kat hadn’t made it back<br />

yet, but she had just called. It was one<br />

o’clock.<br />

“Is she gone?” She asked Jenn’s niece<br />

without being prompted.<br />

“She’s in heaven now,” her niece<br />

whispered as we performed our rituals.<br />

Maybe it brought her some comfort to<br />

say that.<br />

I Googled her name until her obituary<br />

was finally posted. It took the family<br />

over a week to put her in the ground.<br />

Until that time, I knew that Kat must<br />

have been surrounded by Jenn’s family<br />

coming in and out, strangers sending<br />

things like flowers and meat trays. I<br />

decided I would give her a call a couple<br />

days after the funeral. I know from<br />

my own experience that that’s when<br />

the mourning will start—when the<br />

crowds quiet down, and Kat is left to<br />

pick through Jenn’s closet, sleep in the<br />

sheets that smell like her, throw out<br />

the pill bottles that litter her cabinets,<br />

dispose of the relics that documented<br />

the presence of her and the life they’d<br />

built together. She’d be stuck wondering<br />

if she should dispose of everything that<br />

made the longing burn fresh or worry<br />

about whether it would make her forget<br />

something sacred about them. An old<br />

shirt, a matchbook, a used pencil, a half<br />

eaten sandwich. She’d want to reach out<br />

to someone to help her decide what to<br />

keep and realize that her habit for years<br />

now was to reach for Jenn.<br />

“I just wanted you to know that your<br />

relationship is really inspiring.” This was<br />

a couple hours before Jenn’s death when<br />

I found Kat in the room by herself. She<br />

cried. I think it was something that had<br />

built up for a while, and now she just<br />

couldn’t control it.<br />

“Twelve years is just not enough,” she<br />

said, sniffing and shaking her sore, red<br />

face, “but, you know, fifty wouldn’t have<br />

been enough.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> author’s address is:<br />

4249 West Sarah Street<br />

Burbank, California 91505<br />

E-mail: susielisa@gmail.com<br />

Musings on an Attic Tetradrachm<br />

What hands are these that stamped wide-eyed<br />

Owls on rounds of Laurian silver,<br />

And whose knives are those who carved<br />

Humanity on blocks of solid stone?<br />

What artist’s brush has painted antic<br />

Nymphs on urns of reddened clay,<br />

And whose minds are they who plumbed<br />

So deep within the human soul?<br />

Whose book is this which tells such tales of<br />

Bloody death on ancient Trojan shores,<br />

What princely youth has led his men<br />

To trample vast miles of Asian soil?<br />

And which men with their lines and angles<br />

First measured the circumference of the Earth?<br />

Now seek ye out the Olympian gods,<br />

And as the Delphic Sybil nods,<br />

Athena’s owl will tell you Who<br />

Alvin J. Cummins, MD<br />

Dr. Cummins (AΩA, Johns Hopkins University, 1944) is retired as professor of Medicine at the<br />

University of Tennesseee Center for the Health Sciences in Memphis. His address is: 13114 Brooks<br />

Landing Place, Carmel, Indiana 46033. E-mail: nero6@aol.com.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 15

��������<br />

Victim testifies at the Nuremberg Trials. <strong>The</strong> Doctors Trial<br />

considered the fate of twenty-three German physicians who<br />

either participated in the Nazi program to euthanize persons<br />

or who conducted experiments on concentration camp prisoners<br />

without their consent. Sixteen of the doctors charged<br />

were found guilty. Seven were executed.<br />

16 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong><br />

© dpa/dpa/Corbis

����<br />

Political violence and the physician<br />

Amanda J. Redig, MD, PhD<br />

<strong>The</strong> author (AΩA, Northwestern University, 2010) is a<br />

resident in the Department of Medicine at Brigham and<br />

Women’s Hospital in Boston. This essay won second prize<br />

in the 2010 Helen H. Glaser Student Essay Competition.<br />

Human health in the early days of a new millennium<br />

stands at the crossroads of a paradox: thanks to a vast<br />

increase in knowledge and technology, we are more<br />

effective than ever before in both the saving and the taking of<br />

lives. Indeed, the twentieth century is characterized by two<br />

incongruous realities. On the one hand, we have the hope and<br />

optimism generated by groundbreaking strides against the suffering<br />

caused by disease. Yet coupled to such progress is the<br />

dark legacy of genocide, war, and political violence on a scale<br />

previously unimaginable. What makes reconciling these two<br />

competing visions so difficult for the medical profession is the<br />

fact that physicians have been instrumental in advancing not<br />

only the achievements but also the atrocities.<br />

Decades after their deaths, physicians such as Jonas Salk<br />

or Alexander Fleming remain household names because of<br />

the effect their work has had on the advancement of medicine’s<br />

ability to heal. In contrast, there are also physicians<br />

whose names have become synonymous with the very worst<br />

of humanity, such as the “Angel of Death,” Dr. Josef Mengele.<br />

Fortunately, there are far more famous than infamous physicians,<br />

but no matter how much the medical profession may<br />

wish to think otherwise, the physician who chooses to embrace<br />

death over life is not an anomaly.<br />

<strong>The</strong> list of physicians who have participated in and furthered<br />

political violence is extensive. Nazi physicians directed<br />

the mass murder of the weak, the ill, and the disabled in 1930s<br />

Germany, as well as the horrific medical experiments of Nazi<br />

World War II concentration camps. Japan’s World War II<br />

Project 731, led by Dr. Shiro<br />

Ishii, killed thousands of POWs<br />

and Chinese and Soviet citizens<br />

in experiments on germ warfare<br />

and vivisection. Among other<br />

historic firsts, including leadership<br />

of the first organization<br />

to use hijacked airliners as a<br />

political tool, Palestinian pediatrician<br />

George Habash was also<br />

responsible for orchestrating a<br />

rocket attack on a bus full of<br />

children in which nine passen-<br />

Major Nidal Hasan<br />

HO/Reuters/Corbis<br />

gers died. Out of the violence that turned neighbor against<br />

neighbor in the former Yugoslavia, psychiatrist Radovan<br />

Karadzic is currently standing trial in the Hague for his role<br />

in the massacre of Bosnian Muslims at Srebenica and the<br />

Siege of Sarajevo. Al-Qaeda counts numerous physicians as<br />

operatives, from number two Ayman al-Zawahiri to the individuals<br />

responsible for the failed suicide bombing at Glasgow<br />

International Airport in 2007. Most recently, Fort Hood<br />

psychiatrist Major Nidal Hasan was responsible for the worst<br />

attack of terrorism on a domestic U.S. military installation in<br />

American history.<br />

Clearly, incongruity aside, physicians are not exempt from<br />

participation in the most chilling of crimes against humanity.<br />

Despite the repugnance with which most physicians view<br />

such actions on the part of their colleagues, the fact remains<br />

that politically-motivated violence perpetrated by physicians<br />

happens far too often, across all lines of politics, religion,<br />

and ethnicity. <strong>The</strong> questions to be asked are thus far more<br />

complex than whether or not a profession built on the best of<br />

intentions can exist side by side with great evil. Instead, the<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong> 17

<strong>The</strong> monsters of medicine<br />

medical profession must face far more nuanced questions that<br />

are much more difficult to answer. Why do some physicians<br />

act as if some lives have no value? What do their actions mean<br />

for those choosing instead to live by primum non nocere? It<br />

is too simplistic to dismiss the Mengeles and al-Zawahiris<br />

among us as either terrorists or sociopaths. <strong>The</strong> medical profession<br />

needs to go through the potentially painful process<br />

of looking inward to recognize both its unique strengths and<br />

weaknesses. After all, we remember the names of medicine’s<br />

most infamous members not because of their heinous deeds<br />

but rather because such actions were carried out by doctors.<br />

Consequently, we must look more closely at the roots of terrorism<br />

and state-led violence to understand both the physicians<br />

who embrace them, as well as those who do not.*<br />

Internal pressure: surely they must be mad<br />

<strong>The</strong> first explanation often used to make sense of physician<br />

violence is mental illness. <strong>The</strong> gulf that divides what a physician<br />

is supposed to do and what some physicians have done is<br />

so vast that it is not surprising we question the sanity of those<br />

we cannot understand. <strong>The</strong> sociopathy defense provides society—and<br />

especially the medical community—with a mental<br />

escape from the possibility that a sane individual, someone<br />

who could be any of us, would willingly engage in such horrors.<br />

At a superficial level, this initial impression seems accurate<br />

as a way of explaining aspects of both barbarism that<br />

defies words and actions that are so contradictory they cannot<br />

be reconciled. <strong>The</strong> Holocaust and the campaign in the Pacific<br />

are among the most extensively analyzed and referenced topics<br />

in the historical literature,<br />

yet the details of the medical<br />

torture that took thousands of<br />

lives still remain in the shadows.<br />

<strong>The</strong> thought of physicians<br />

removing organs or limbs from<br />

live patients without anesthesia,<br />

spinning people in centrifuges<br />

until they died, or using prisoners<br />

tied to posts to test the efficacy<br />

of flame-throwing devices<br />

stand apart as too horrific to<br />

contemplate. And what could be<br />

more contradictory than an individual<br />

who chooses a career as a<br />

physician and then participates<br />

Dr. Josef Mengele<br />

© Bettmann/CORBIS<br />

in political violence? Several of<br />

the physicians implicated in the<br />

* In this paper “terrorism” refers to Paul Wilkinson’s definition of<br />

“violence or the threat of violence,” here used primarily in reference<br />

to non-state actors. 1 “State-led violence” is used for similar actions,<br />

specifically war crimes and genocide, orchestrated by state actors.<br />

<strong>The</strong> word “violence” is used exclusively to refer to actions that have<br />

an underlying political nature, regardless of the organizational level<br />

at which such goals are pursued.<br />

Glasgow International Airport suicide<br />

bombing plot were not only<br />

practicing medicine at the time<br />

but were also living among the<br />

very people they were attempting<br />

to destroy. <strong>The</strong> duality of treating<br />

one’s neighbors by day and plotting<br />

to blow them up at night makes no<br />

sense. Even though Major Nidal<br />

Hasan’s trial has not yet begun, it<br />

is assumed that he will use an insanity<br />

defense because his actions<br />

are so at odds with his professional<br />

career. <strong>The</strong> DSM-IV definition of<br />

antisocial personality disorder—<br />

the preferred way of referencing<br />

the sociopath of common usage—<br />

Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri<br />

AFP/Getty Images<br />

includes at its core a lack of regard for the rights of others. 2<br />

In this sense, at least, the actions of such infamous physicians<br />

seem to fit.<br />

Yet, a closer examination of the actions of these physicians<br />

makes it clear that mental illness does not explain their atrocities.<br />

<strong>The</strong> DSM definition of antisocial personality disorder<br />

is far more complex than the superficial understanding of a<br />

person who does the unthinkable; it also includes several essential<br />

criteria, starting with a pervasive pattern of disregard<br />

for and violation of the rights of others occurring since the age<br />

of fifteen. 2 Patients with this disorder must also meet three (or<br />

more) of the following:<br />

1. failure to conform to social norms with respect to lawful<br />

behaviors as indicated by repeatedly performing acts that<br />

are grounds for arrest<br />

2. deceitfulness, as indicated by repeated lying, use of<br />

aliases, or conning others for personal profit or pleasure<br />

3. irritability and aggressiveness, as indicated by repeated<br />

physical fights or assaults<br />

4. reckless disregard for safety of self or others<br />

5. consistent irresponsibility, as indicated by repeated<br />

failure to sustain consistent work behavior or honor financial<br />

obligations<br />

6. lack of remorse, as indicated by being indifferent<br />

to or rationalizing having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from<br />

another. 2<br />

This more nuanced pattern does not entirely fit any of the<br />

physicians whose crimes the profession would like to forget.<br />

<strong>The</strong> very act of choosing a career in medicine and completing<br />

medical school makes psychopathology at a level that<br />

encompasses mass murder untenable. Medicine is a profession<br />

entered as an adult with extensive emphasis on social norms<br />

and regulated, responsible behavior, and for which consistency<br />

in meeting numerous obligations is essential. While it<br />

is clear that something is grievously wrong with physicians<br />

like Mengele and his ilk, attributing even the most despotic<br />

18 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Pharos</strong>/<strong>Winter</strong> <strong>2011</strong>

Dr. Karl Brandt at the Nuremberg trial.<br />

© dpa/Corbis<br />

of actions solely to psychiatric disease misses an essential, if<br />

unsettling, element of the dark side of physician behavior: they<br />

were once just like us.<br />

Nazi physician Karl Brandt was the director of the T-4<br />

euthanasia program that murdered thousands of Germans<br />

before it became the inspiration for the gas chambers of the<br />

death camps. At his trial at Nuremberg, Brandt said this:<br />

Would you believe that it was a pleasure to me to receive<br />