Walking the Talk - VSO

Walking the Talk - VSO

Walking the Talk - VSO

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

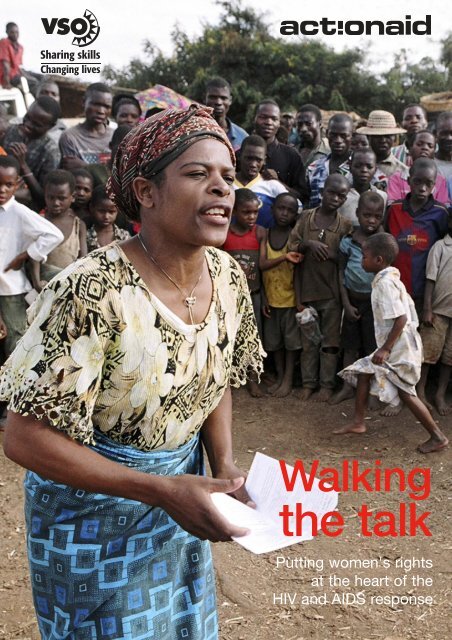

<strong>Walking</strong><strong>the</strong> talkPutting women's rightsat <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong>HIV and AIDS response

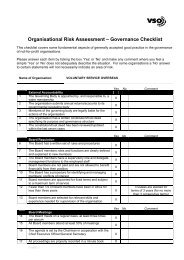

Cover Photo: Gideon Mendel/Corbis/ActionAidRuth Nkuya, who is living with HIV and AIDS and taking antiretroviral medication, talksto a participant in an HIV and AIDS education drama at <strong>the</strong> market place in NgwenyaLocation, Lilongwe, Malawi.AcknowledgementsAuthors: Nick Corby, Nina O'Farrell, Mike Podmore and Carmen Sepúlveda ZelayaEditors: Vicky Anning, Christian Humphries and Jenny DrezinResearch assistants: Maria Adelantado and Rebecca SinclairDesign: Academy Design PartnersWith thanks to all ActionAid and <strong>VSO</strong> staff, volunteers and partners whocontributed to <strong>the</strong> country research, including:Christy Abraham, Solomon Adebayo, Samia Ahmed, Maria Amjad, Juliet Bavuga,Smriti Bhattarai, Menno Bongers, Tasallah Chibok, Winston Chirombe, WedzeraiChiyoka, Dr. Rumeli Das, Charlotte Vidya Dais, Wubishet Desinet, Arturro Echeverria,Alma de Estrada, Nontuthuzelo Fuzile, Gezahagn Gezachew, Cynthia Gobrin-Sono,Shukria Gul, Innocent Hitayezu, Mohammed Kamal Hossain, David Lankester, AnchitaJahatik, Faiza Javaid, Sara Joseph, Farah Kabir, Lute Kazembe, Dr P. Manish Kumar,Etelvina Mahanjane, Vidyacharan Malve, Aveneni Mangombe, Shiji Malayil, Maia Marie,Sipho Mtathi, Dagobert Mureriwa, Lutfun Nahar, Hannah Pearce, Roberto Pinauin,Stephen Porter, Claudia Areli Rosales, Sanjay Singh, Sudhir Singh, Shyamalangi,Srinivas, Rimmy Taneja, Carine Terpanjian, Chinyere Udonsi, Whelma Villar-Kennedy,Lumeng Wang, Annemieke van Wesemael, Mohammad Arif Yusuf, Kazi KarishmaZeenat, Qingtian Zheng.With thanks for <strong>the</strong>ir input to:Avni Amin, Emma Bell, Brook Baker, Belinda Calaguas, Sara Cottingham, MartaMontesó Cullell, Leona Daly, Dorothy Flatman, Susana Fried, Gerard Howe, RichardHowlett, Beri Hull, Dieneke Ter Huurne, Clive Ingleby, Kate Iorpenda, Anne Jellema,Susan Jolly, Agnes Makonda Ridley, Joe McMartin, Malcolm McNeil, Bongai Mundeta,Neelanjana Mukhia, Fionnuala Murphy, Lina Nykanen, Leonard Okello, Luisa Orza,Jacqueline Patterson, Kousalya Periasamy, Fiona Pettitt, Maria Alejandra Scampini,Andy Seale, Aditi Sharma, Alan Smith, Asha Tharoor, Laura Turquet, Mary Wandia,Patrick Watt, Samantha Willan, Kemi Williams, Everjoice Win, Jessica Woodroffe.

ContentsContents 1Glossary 2Definitions 3Executive summary 51. Introduction 91.1. Structure of <strong>the</strong> report 101.2. Methodology 101.3. Overview: <strong>the</strong> feminisation of HIV and AIDS 111.4. Universal access: what is it and why arewe using it as a framework? 111.5. Why take a rights-based approachto universal access? 121.6. Achieving a rights-based approachto universal access 131.7. Gender, poverty and HIV and AIDS 132. Gender inequality, women’s rights andHIV and AIDS 142.1. Sexual and reproductive rights andviolence against women 142.2. Right to <strong>the</strong> highest attainable standardof health 162.3. Poverty and economic rights 172.4. Recommendations 184. Women’s rights and universal access toeffective treatment 304.1. Access to treatment: is <strong>the</strong>re agender bias? 314.2. Adherence to treatment: it’s not justabout access 324.3. ART in resource limited settings 344.4. Recommendations 345. Women’s rights and universal access toHIV and AIDS care and support 365.1. What do we mean by ‘care and support’? 375.2. Women and girls’ access to care andsupport services 375.3. Women and girls providing care andsupport services 405.4. The impact of providing care andsupport on women and girls 425.5. Recommendations 476. Conclusion 507. Endnotes 523. Women’s rights and universal access toHIV prevention 203.1. Women’s right to education andinformation 213.2. Technologies and medical interventions:putting prevention directly in women'shands 243.3. Services: prevention of mo<strong>the</strong>r-to-childtransmission-Plus 273.4. Services: voluntary counsellingand testing 283.5. Recommendations 29<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 1

GlossaryABC‘Abstinence, Be faithful, Condom use’INGOInternational non-governmentalapproachorganisationACHRAmerican Convention on Human RightsLGBTQILesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, queer,(1968)intersexACHPRProtocol of <strong>the</strong> African Charter on HumanMDGsMillennium Development Goalsprotocoland People’s Rights on <strong>the</strong> Rights ofWomen in Africa (2003)NGONon-governmental organisationAIDSAcquired Immune Deficiency SyndromePEPPost-exposure prophylaxisARTAntiretroviral <strong>the</strong>rapyPEPFARPresident’s Emergency Plan for AIDS ReliefARVsAntiretroviralsPITCProvider initiated testing and counsellingCAAPConfidential Approach to AIDS PreventionPLWHAPeople living with HIV and AIDSCBOCommunity-based organisationPMTCTPrevention of mo<strong>the</strong>r-to-child transmissionCEDAWConvention on <strong>the</strong> Elimination of All FormsPPTCTPrevention of parent-to-child transmissionof Discrimination Against Women (1981)PWN+Positive Women’s Network, IndiaCHBCCommunity home-based careSIDASwedish International Development AgencyCRCConvention on <strong>the</strong> Rights of <strong>the</strong> ChildSRHSexual and Reproductive HealthCSOCivil society organisationSRHRSexual and Reproductive Health RightsDFIDDepartment for International DevelopmentSTISexually Transmitted InfectionUKTACTreatment Action CampaignFBOFaith-based organisationUDHRUniversal Declaration of Human RightsFGMFemale genital mutilation(1948)GBVGender-based violenceUNAIDSJoint United Nations Programme onHIVHuman Immunodeficiency VirusHIV/AIDSICPDInternational Conference on Population andUNFPAUnited Nations Population FundDevelopment (1994)UNIFEMUnited Nations Fund for WomenICCPRInternational Covenant on Civil and PoliticalVAW/GViolence against women and girlsRights (1966)VCTVoluntary counselling and testingICESCRInternational Covenant on Economic, Socialand Cultural Rights (1966)WHOWorld Health OrganizationICWInternational Community of Women Livingwith HIV/AIDS2 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

DefinitionsUniversal Universal access is <strong>the</strong> most recent andaccess comprehensive commitment made by <strong>the</strong>‘continuum’ international community in response toHIV and AIDS. The ‘continuum’ iscomposed of prevention, treatment, careand support – four indivisible pillars of aneffective response to HIV and AIDS.Civil society Civil society is composed of diverse actorsand institutions such as charities, nongovernmentalorganisations, communitybasedorganisations and groups, women'sorganisations, faith-based organisations,professional associations, self-help groups,networks of people living with HIV andAIDS, social movements, coalitions,advocacy groups etc.International A body of treaties, charters, covenants,human rights bills of rights, declarations and o<strong>the</strong>rinstruments international legal instruments thatgovernments have agreed or signed.Rights Individuals and groups with rights asholders defined in International HumanRights Instruments.Duty bearers State or non-state actors responsible andaccountable for ensuring rights, as definedin International Human Rights Instruments,are respected, protected and fulfilled.Empowerment The process through which women andgirls come to see <strong>the</strong>mselves as havingentitlements and rights and identify <strong>the</strong>power <strong>the</strong>y and o<strong>the</strong>rs have to claimthose entitlements.Women’s The capacity of women to act individuallyagency or within a group, to start an empowermentprocess and to <strong>the</strong>n regain control andmake choices in <strong>the</strong>ir life.SexGenderSexualityGenderequalityPMTCT-PlusThe characteristics of human biology andanatomy that define males and females;sexual intercourse.Socially constructed characteristics,qualities and behaviours, assigned tohuman beings according to <strong>the</strong>ir sex,against which women and menare measured.Encompasses sex, gender identities androles, sexual orientation, eroticism,pleasure, intimacy and reproduction.Includes thoughts, fantasies, desires,beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviours,practices, roles and relationships.Sexuality is influenced by <strong>the</strong> interaction ofbiological, psychological, social,economic, political, cultural, ethical, legal,historical, religious and spiritual factors. 1The right of both sexes to equal rightsand opportunities, and to be free fromdiscrimination established throughgender norms.Unlike simple prevention of mo<strong>the</strong>r-tochildtransmission programmes (PMTCT)that put <strong>the</strong> burden of prevention oftransmission to <strong>the</strong> newborn exclusivelyon women, PMTCT-Plus involves everyfamily member infected or affected by HIVand AIDS. It is a more holistic set ofservices for pregnant women living withHIV and AIDS, providing preventative<strong>the</strong>rapy, treatment and care for women in<strong>the</strong>ir own right (including treatmentoptions beyond pregnancy). PMTCT-Plusencourages <strong>the</strong> participation of men at allstages of pregnancy, delivery and care aswell as on issues around stigma andpositive status disclosure.<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 3

PositivelivingA term used to describe a way of living afull and healthy life with HIV and AIDSincluding mental, physical and emotionalhealth. Positive living can include goodnutrition, accessing treatment including foropportunistic infections, and withpsychosocial, spiritual, emotional andcommunity support.Primary care Family members or close friends whoprovider provide care and support in <strong>the</strong> home.Secondary Visiting nurses, health workers orcare provider community care providers from NGOSor community groups. They provide arange of services for people living withHIV and AIDS.SerodiscordantVerticaltransmissionA term used to describe a couple in whichone partner is living with HIV and AIDSand <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r is not.Vertical transmission, also known asmo<strong>the</strong>r-to-child transmission refers totransmission of an infection, such as HIV,hepatitis B, or hepatitis C, from mo<strong>the</strong>r tochild during <strong>the</strong> perinatal period, <strong>the</strong>period immediately before and after birth.4 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

Gideon Mendel/Corbis/ActionAidAderonke Afolabi, founder of <strong>the</strong> support organisation PotterCares in Nigeria, is one of <strong>the</strong> few people in <strong>the</strong> country livingopenly with HIV and AIDS.Executive summaryIt is time to walk <strong>the</strong> talk on women, human rights and universal access toHIV and AIDS services. We call on decision-makers to take urgent andpractical action to ensure that women and girls’ rights are recognised as anessential foundation for achieving universal access to prevention, treatment,care and support.<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 5

Rights violations drive <strong>the</strong> pandemicUsing research from 13 countries, this reportdemonstrates that gender inequalities and <strong>the</strong>persistent and systematic violation of <strong>the</strong>ir rights areleaving women and girls disproportionately vulnerable toHIV and AIDS. Poverty and limited access to educationand information, discriminatory laws and ingrainedgender inequalities all deny women and girls <strong>the</strong>ir rights.Gender-based violence, health systems that serve <strong>the</strong>needs of women poorly and limited participation indecision-making processes all fuel <strong>the</strong> feminisation of<strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS epidemic.Globally <strong>the</strong> percentage of women and girls living withHIV and AIDS has risen from 41% in 1997, to just below50% today, while in sub-Saharan Africa, 75% of 15 to24-year-olds living with HIV and AIDS are female. Thisreport shows that it is poor, rural women who are amongthose hit hardest by <strong>the</strong> profound health, economic andsocial impacts of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS epidemic.We have known for some time that while women andgirls are disproportionately affected by HIV and AIDS,<strong>the</strong>y still provide <strong>the</strong> backbone of community supportand play critical roles as agents of change, activists andleaders. However, responses to HIV and AIDS still donot reflect <strong>the</strong>se realities.Universal access and women’s rights: <strong>the</strong>framework for actionThere are only two years left to meet <strong>the</strong> commitmentby governments and donors to ‘universal access toprevention, treatment, care and support by 2010’ forthose affected by HIV and AIDS. The only effective wayto realise this commitment is to promote a women’srights-based and gender-sensitive approach.Our call to actionOur report lays responsibility for making <strong>the</strong>se changes firmly with thosewho hold power and bear <strong>the</strong> duty to respect, protect, promote and fulfilrights – national governments, donors and multilateral organisations and, tosome extent, civil society. Our report balances this with <strong>the</strong> essentialpromotion of women and girls as rights holders, activists and leadersof change.6 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

Prevention, treatment and care and supportIn every aspect of prevention, treatment and care and support, women and girls are regularly unable toexercise <strong>the</strong>ir rights to access HIV and AIDS services. In this report we detail <strong>the</strong> barriers for women andgirls in terms of prevention, treatment and care and support, and suggest recommendations. We summarise<strong>the</strong>se recommendations below.Prevention“…my husband tested positive before me,but my aunties, toge<strong>the</strong>r with my latehusband, disapproved of condom use,arguing that he had paid up all <strong>the</strong> bridewealth and <strong>the</strong>refore [I] was supposed notto deny him sex, unprotected or not… <strong>the</strong>yaccused condom use with lack of love formy late husband… everyone was againstme and [I] had no option…”Strategies to prevent HIV infection often fail to take intoaccount <strong>the</strong> real lives of women and girls. Preventionstrategies based on abstinence, being faithful and usinga condom ignore <strong>the</strong> lack of control most women haveover <strong>the</strong>ir sexuality and <strong>the</strong> violence women face,particularly within marriage. The development ofprevention methods that women can control (femalecondoms and microbicides) will help, as will educationand public awareness campaigns that promotewomen’s rights.National and donor governments must only fundevidence-based, gender-sensitive preventionprogrammes that take a rights-based approach,including contributing <strong>the</strong>ir fair share to <strong>the</strong>development of microbicides and increasing access to<strong>the</strong> female condom and o<strong>the</strong>r female-initiated HIVpreventionmethods.TreatmentZimbabwean woman living with HIV and AIDS“How can I get up at 3am <strong>the</strong>n travel aloneduring <strong>the</strong> night to make sure I getantiretrovirals? But a man can easily walkduring <strong>the</strong> night.”Women are more likely to receive treatment than men, butour research suggests <strong>the</strong>y may be less likely to adhere toit. Reasons given are <strong>the</strong> lack of privacy and <strong>the</strong> fear ofviolence or abandonment if <strong>the</strong>ir positive status isdiscovered. Women also have less access to adequatenutrition, which <strong>the</strong>y need to support <strong>the</strong>ir treatment. Ifaccess to treatment is to be increased, <strong>the</strong> particularbarriers for women will also have to be addressed.National governments must develop, fund andimplement <strong>the</strong>ir national treatment plans and budgetswith a strong emphasis on <strong>the</strong> access and adherenceof women and girls to treatment, particularly those inpoor and rural communities.Care and support“We walk for miles and miles in order toreach clients in o<strong>the</strong>r homesteads. Oncewe are <strong>the</strong>re clients expect a lot from us,like food and even money. This putspressure on our personal resources.”Namibian care providerWomen living with HIV and AIDS face significantbarriers in getting <strong>the</strong> care and support <strong>the</strong>y need.Leadership of support groups is often dominated bymen, with women and girls unable to raise <strong>the</strong>irconcerns. The problem is particularly difficult forwomen living in poverty, who don’t have access to <strong>the</strong>income generation opportunities or state services <strong>the</strong>yneed to provide for <strong>the</strong>mselves or <strong>the</strong>ir families.Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, women and girls are <strong>the</strong> major careproviders, yet <strong>the</strong>y are seldom paid and <strong>the</strong> value ofthis work is rarely recognised.Rwandan woman living with HIV and AIDS<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 7

Cross-cutting recommendations• National and donor governments should basenational AIDS plans on a rights-based analysis of <strong>the</strong>barriers faced by women and girls in regard to HIVand AIDS prevention, treatment, care and supportservices. UNAIDS and <strong>the</strong> World Health Organizationmust develop clear targets, guidelines and a singlestrategy to support country governments to do this.• National and donor governments should consultwith women’s movements, local networks andmovements of women living with HIV and AIDS toensure funding reflects local priorities. They shouldalso ensure that <strong>the</strong>ir policies and programmes donot reinforce inequalities and have <strong>the</strong> participation ofwomen and girls living with (and affected by) HIV andAIDS at <strong>the</strong>ir heart.• National and donor governments should ensurelong-term, predictable funding for <strong>the</strong> streng<strong>the</strong>ning ofhealth systems, in particular to ensure women-friendlyand pro-poor health systems that integrate HIV andAIDS and sexual and reproductive health rightsservices with HIV and AIDS prevention, treatment, careand support services. This should include adequatestaffing, diagnostics, medicines and o<strong>the</strong>r provisions totreat opportunistic infections that particularly affectwomen and girls, such as cervical cancer.• The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis andMalaria should improve expertise on women’s rightsat all levels of <strong>the</strong> decision-making process, anddevelop adequate indicators to monitor that countrycoordinating mechanisms are reflecting <strong>the</strong> prioritiesand rights of women and girls.• Civil society should undertake advocacy and raiseawareness around women’s rights to HIV and AIDSprevention, treatment, care and support, as well ashold governments to account for <strong>the</strong> realisation of<strong>the</strong>se rights. They should also increase meaningfulinvolvement of women in leadership and decisionmakingpositions in <strong>the</strong>ir organisations to ensureissues related to women and girls’ rights areprioritised in <strong>the</strong>ir workWorldwide commitment to <strong>the</strong> universal access goal– and <strong>the</strong> universal access process itself – providesan opportunity to streng<strong>the</strong>n advocacy for women’srights. Moving from recognition of <strong>the</strong> feminisationof HIV and AIDS to action is a major challenge. Todate, this challenge has been met by devastatinginaction. The solution requires both politicalcommitment and resources. Those with power mustlisten to women’s priorities, uphold <strong>the</strong>ir right toparticipation, support <strong>the</strong>ir empowerment andchallenge those who violate <strong>the</strong>ir rights.“When my husband was ill I went with my husband for medication, but when I’m ill I talk to<strong>the</strong> NGO staff.”Woman living with HIV and AIDS, Pakistan8 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

Gideon Mendel/Corbis/ActionAidStreet vendors trained as HIV and AIDS educators perform aneducational song in Bobole in Mozambique. They aim <strong>the</strong>irmessage at truck drivers who buy <strong>the</strong>ir produce.1. IntroductionMost governments have committed to ensuring <strong>the</strong>rights of women and girls through <strong>the</strong> legal frameworks“The HIV/AIDS epidemic has put <strong>the</strong>spotlight on deep-rooted constraints thathold women back in many areas of life.Traditional attitudes and behaviourschange gradually, sometimes over severalgenerations. This epidemic gives us nosuch luxury of time.” 2Dr Margaret ChanDirector-General of <strong>the</strong> World Health Organizationof international human rights. However, growingfeminisation of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS pandemic is damningproof of <strong>the</strong> failure by governments to deliver on <strong>the</strong>ircommitments. Gender inequality, violence againstwomen and o<strong>the</strong>r violations of women’s rights arecritical drivers of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS pandemic. Studieshave affirmed gender norms to be among <strong>the</strong> strongestunderlying social factors influencing sexual behaviourand HIV risk. Similarly, women and girls living with HIVand AIDS may experience particular stigma,discrimination and increased violence if <strong>the</strong>ir HIV statusis disclosed. Despite <strong>the</strong> overwhelming evidence of <strong>the</strong>importance of discrimination against women, it has notbecome an integral aspect of <strong>the</strong> global AIDS response.By failing to acknowledge and respond to genderedaspects of <strong>the</strong> pandemic, not only are governmentsfalling short on <strong>the</strong>ir commitments, <strong>the</strong>ir efforts to stem<strong>the</strong> spread of HIV and AIDS are destined to fail.This report argues that only a rights-based approachcan redress <strong>the</strong> current failures and support women in<strong>the</strong> response to HIV and AIDS. While firmly anchored in<strong>the</strong> treaties, declarations and commitments that make<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 9

up international law, a rights-based approach placespeople squarely at <strong>the</strong> centre of <strong>the</strong> agenda. Itempowers women and girls to claim <strong>the</strong>ir rights, andtake control of <strong>the</strong>ir bodies and lives. It puts women andgirls at <strong>the</strong> heart of policies and programmes, ensuring<strong>the</strong>ir meaningful participation by making governmentsand institutions accountable to <strong>the</strong>m. It also placesresponsibilities on men and boys for respecting andpromoting women’s rights. It is our hope that this reportwill contribute to international advocacy efforts that gobeyond mere rhetoric and make a tangible difference in<strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>the</strong> people we serve.1.1. Structure of <strong>the</strong> report“We will not be able to stop this epidemicif we don’t address its drivers in <strong>the</strong> firstplace – gender inequality and itsconsequences for women. This willrequire that we go well beyond <strong>the</strong>gender rhetoric and be more operationalin what we promote.” 3Dr Peter PiotUNAIDS Executive DirectorThis report explores obstacles to universal access toprevention, treatment, care and support for all womenand girls. It illustrates <strong>the</strong> ongoing violations of women’srights by <strong>the</strong> actions and inactions of those settingpolicies, providing funding, offering services andimplementing programmes. It fur<strong>the</strong>r provides workingsolutions and best practices for overcoming thoseobstacles. Such strategies were ga<strong>the</strong>red throughresearch studies conducted in 13 countries in whichActionAid and <strong>VSO</strong> work. While not an exhaustive reviewof women’s rights, it incorporates <strong>the</strong> voices of ourconstituents to bring to life <strong>the</strong> particular challenges forwomen living in <strong>the</strong> era of HIV and AIDS. By weavingsuch everyday stories throughout <strong>the</strong> text, we hope toillustrate that rights are not just abstract principles, butra<strong>the</strong>r tangible tools that fundamentally affect <strong>the</strong>wellbeing of women and girls around <strong>the</strong> world.The report presents an overview of <strong>the</strong> ways in whichwomen’s rights affect every aspect of HIV and AIDSprevention, treatment, care and support. We begin inChapter 2 with an overview of cross-cutting women’srights issues relevant to HIV and AIDS. Chapters 3 to 5<strong>the</strong>n examine <strong>the</strong> many barriers women face in accessingHIV and AIDS prevention (Chapter 3), treatment (Chapter4), care and support, as well as <strong>the</strong> challenges faced bywomen care providers (Chapter 5). Finally, <strong>the</strong> reportconcludes by calling upon governments in rich and poorcountries, as well as donors, multilateral organisations andcivil society, to take specific steps to place women’s rightsat <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong>ir response to HIV and AIDS.Throughout <strong>the</strong> report we have includedrecommendations for incorporating <strong>the</strong> rights of womenand girls in <strong>the</strong> scale up to universal access.Lastly, we use <strong>the</strong> term ’women and girls’ throughout<strong>the</strong> report, while acknowledging that this does notrepresent a homogeneous category. However, werecognise that some women and girls are particularlyvulnerable or marginalised, whe<strong>the</strong>r as a result ofincome, ethnicity, class, caste, religion, sexualorientation, age, disability, profession or o<strong>the</strong>r factors.There are specific challenges to realising <strong>the</strong> rights ofeach of <strong>the</strong>se groups, made more complex andpressing by <strong>the</strong> many ways in which <strong>the</strong>y aremarginalised. While this report does not cover everykind of marginalisation, stories integrated into <strong>the</strong> reporthighlight some of <strong>the</strong> challenges faced by specificgroups in <strong>the</strong> developing world, where ActionAid and<strong>VSO</strong>’s work is focused.1.2. MethodologyThis report is a joint project between ActionAid and<strong>VSO</strong>, conducted between May and November 2007. Itdraws toge<strong>the</strong>r desk-based research at internationallevel and short participatory research projectscommissioned from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Guatemala,India, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan,Rwanda, South Africa, Vanuatu and Zimbabwe.ActionAid and <strong>VSO</strong> programme staff and nationalpartner organisations conducted <strong>the</strong> country levelparticipatory research over a two-month period. Theyused a range of research methods including: focusgroups of women living with HIV and AIDS, as well asspecific vulnerable groups such as sex workers, inaddition to focus groups of community care providers inboth urban and rural settings; semi-structured andin-depth interviews with key policy makers ingovernment, international non-governmentalorganisations (INGOs) and national coordinatinginstitutions; and desk-based surveys of nationalresearch and policy to assess <strong>the</strong> legal and socialcontext affecting women in those countries. Quantitativedata was ga<strong>the</strong>red through desk-based research. Theinformation and stories ga<strong>the</strong>red from focus groupparticipants have both guided <strong>the</strong> content of <strong>the</strong> reportas well as provided its most personal testimony.10 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

Figure 1: Number of women and men living with HIV and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa 1985-200416Number of women and men living withHIV and AIDS – Millions14121086420Women living with HIV and AIDSMen living with HIV and AIDS1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004Year(Source: UNAIDS/WHO estimates 2004)1.3. Overview: <strong>the</strong> feminisation of HIV and AIDSThe ‘feminisation of HIV and AIDS’ is an often quotedrecognition by governments and internationalorganisations that women and girls are increasinglyinfected by HIV and AIDS, and carry many of <strong>the</strong>burdens related to <strong>the</strong> pandemic. Globally, <strong>the</strong>percentage of people living with HIV and AIDS who arewomen and girls has risen sharply from 41% in 1997 4 tojust below 50% today. 5The vulnerability of women and girls to HIV and AIDS isparticularly marked in sub-Saharan Africa. As <strong>the</strong> abovegraph shows, <strong>the</strong> difference in <strong>the</strong> number of womenliving with HIV and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa nowsignificantly outstrips <strong>the</strong> number of men. Women andgirls in this region now represent nearly 60% of all thoseliving with HIV and AIDS, 6 and as much as 75% amongst15 to 24 year olds. In o<strong>the</strong>r regions, an increasingproportion of people living with HIV and AIDS are womenand girls. 7 The reasons for <strong>the</strong> feminisation of HIV andAIDS are complex. As we discuss more extensively inChapter 2, women and girls’ rights violations leave <strong>the</strong>mmore vulnerable to HIV and AIDS and with limited accessto HIV prevention, treatment, care and support services.Understanding <strong>the</strong> role of women and girls’ rights inrespect to achieving universal access to prevention,treatment, care and support is <strong>the</strong>refore crucial.1.4. Universal access: what is it and why are weusing it as a framework?Providing universal access to prevention, treatment,care and support is <strong>the</strong> most recent and comprehensivecommitment made in response to HIV and AIDS by <strong>the</strong>international community. These four pillars are nowrecognised as <strong>the</strong> indivisible elements of an effectiveHIV and AIDS response. First proclaimed by <strong>the</strong> G8countries in 2005 at <strong>the</strong> Gleneagles Summit, andreiterated by o<strong>the</strong>r UN member nations in 2006 at <strong>the</strong>UN High-Level Meeting on AIDS, universal access sets<strong>the</strong> framework for both <strong>the</strong> UN system and, byextension, country-level response. As part of <strong>the</strong>ircommitment, countries promised to set national leveltargets to work towards <strong>the</strong> goal of “universal access tocomprehensive prevention programs, treatment, careand support by 2010”. 8There are two important limitations to using universalaccess as a framework for scaling up women and girls’access to prevention, treatment, care and support. Thefirst refers to <strong>the</strong> actual definition of ‘universal’. While weat ActionAid and <strong>VSO</strong> define ‘universal’ as access foreveryone, UNAIDS has set specific targets forprevention, treatment, care and support. For example,<strong>the</strong> 2010 target for <strong>the</strong> ‘treatment’ goal has been set at80% coverage of those who would die within one yearwithout such treatment. 9 It is important that <strong>the</strong>setargets are seen as a milestone towards reaching <strong>the</strong>ultimate goal of genuinely accessible serviceseverywhere, for everyone.The second limitation refers to <strong>the</strong> importance of (orlack of) gender as a factor in <strong>the</strong> universal accessprocess. Governments ratcheted-up <strong>the</strong> significance ofgender during <strong>the</strong> 2007 G8 summit, <strong>the</strong> first G8meeting both to acknowledge <strong>the</strong> importance ofwomen’s rights in addressing <strong>the</strong> pandemic as well asto expressly make <strong>the</strong> link between HIV and AIDS andsexual and reproductive health. 10 And yet <strong>the</strong> lack of anexplicit mandate to include gender issues on country-<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 11

Gideon Mendel/Corbis/ActionAidA woman comforts her sister who has malaria, in <strong>the</strong> femalegeneral medical ward of Kamazu Central hospital, <strong>the</strong> secondlargest in Malawi.2. Gender inequality,women’s rights and HIVand AIDS“Violence against women is a fact of life inIndia. A woman has <strong>the</strong> duty of pleasingher husband; if she refuses sex, she risksviolence, abuse and abandonment. Thesewomen tolerate <strong>the</strong>ir husband’s infidelityand abuse and submit to <strong>the</strong>ir demandsto avoid fur<strong>the</strong>r abuse, remaining in <strong>the</strong>serelationships for fear of abandonment.The culture of silence is maintained andmany view this violent relationship as‘normal’.” 15 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk research, India, 2007Gender bias undermines <strong>the</strong> universal access effort atevery step – from prevention to treatment, to care andsupport. This chapter explores some of <strong>the</strong> rights ofwomen and girls that cut across <strong>the</strong> universal accesscontinuum. We have grouped <strong>the</strong> rights under broadercategories of sexual and reproductive rights, right to <strong>the</strong>highest attainable standard of health, and economic rights.As HIV and AIDS is not just a health issue, but an issue ofsocial, cultural and economic inequalities, we focus on <strong>the</strong>interplay of abuses of <strong>the</strong>se rights in hindering <strong>the</strong> universalaccess process for women and girls.2.1. Sexual and reproductive rights and violenceagainst womenAll people have <strong>the</strong> right to control what happens to<strong>the</strong>ir bodies and to make personal decisions regardingwhen, how, and with whom <strong>the</strong>y have sex. ‘Sexualrights’ refers to sexuality and human rights associatedwith physical and mental integrity, including <strong>the</strong> right toa safe sex life, <strong>the</strong> right to choose an intimate or lifepartner, and <strong>the</strong> right to sexual health information andservices. Yet <strong>the</strong> prevalence of violence against womenmeans that countless women around <strong>the</strong> world aredenied that basic right. Whe<strong>the</strong>r forced into sex throughexpressly violent means, or coerced through early14 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

marriage, harassment or o<strong>the</strong>r societal pressure,women are often at great risk of contracting HIV.Indeed, <strong>the</strong>re is widespread recognition that HIV andAIDS cannot be addressed effectively withoutspecifically addressing violence against women,particularly sexual violence. 16 The two issues areinextricably linked. HIV and AIDS are recognised as botha cause of violence (eg following a positive test) and aconsequence of it (eg through rape or domesticviolence). Domestic violence, rape and harmfultraditional practices such as female genital mutilation(FGM) all increase women’s risk of infection. Youngwomen and girls are at particular risk of infection since<strong>the</strong>y are more biologically vulnerable and may have lesscontrol over <strong>the</strong>ir sexuality.Gender-based violence strips women of <strong>the</strong>ir physicalautonomy and is explicitly or implicitly used by men as ameans of control, enforcing many of <strong>the</strong> genderinequalities that we shall explore in this chapter. Recentresearch by <strong>the</strong> World Health Organization shows thatsexual violence, particularly by an intimate partner, is aleading factor in <strong>the</strong> increasing ‘feminisation’ of <strong>the</strong>global AIDS pandemic. 17 However, recent research by<strong>the</strong> Women won’t wait campaign has confirmed thatthis recognition is not yet reflected consistently (or,sometimes, at all) in <strong>the</strong> policies, programming andfunding priorities of governments and donors at <strong>the</strong>national, regional and international level. 18The right to enter into marriage freely and to equality inmarriage also affects women’s – and in particular younggirls’ – likelihood of contracting HIV, as well as <strong>the</strong>irability to seek treatment, care and support. Worldwidetrends show that married women may in fact be atgreater risk than unmarried women for contracting <strong>the</strong>disease. In Bangladesh, for example, one focus groupwith women belonging to <strong>the</strong> self-help group MUKHTOAKASH, stressed that <strong>the</strong> majority of women living withHIV and AIDS are married women infected by <strong>the</strong>irhusbands, who are often migrant workers, or inmonogamous relationships. 19 Indeed, <strong>the</strong> executivedirector of <strong>the</strong> Confidential Approach to AIDSPrevention (CAAP), argued that in Bangladesh it iswidely considered a “man’s innate right to indulge inunsafe sex with <strong>the</strong>ir wives. These women are infectedby <strong>the</strong>ir husbands and <strong>the</strong>n are blamed by society forinfecting <strong>the</strong>ir husbands.” 20 In Rwanda, members of afocus group reported how <strong>the</strong>ir husbands had beaten<strong>the</strong>m because <strong>the</strong>y once refused to have sex if nocondom was used. 21 Sexual rights are often abridged in<strong>the</strong> case of an ‘early’ or child marriage, especially wherea dowry has been paid. Dowries are often considered‘an outright purchase of a wife’. 22 As a result, wiveswho do not ‘measure up’ may be denied information orcontrol over <strong>the</strong>ir lives and in some cases are victimsof violence. 23Reproductive health and rights are also critical forstemming <strong>the</strong> spread of HIV and AIDS. A majority of HIVinfections worldwide are sexually transmitted or areassociated with pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.Women who become pregnant after sex with aninfected partner face particular challenges. Thesewomen are more likely to be aware of <strong>the</strong>ir HIV status,because of <strong>the</strong> prevalence of pre-natal testing.However, women living with HIV and AIDS may beadvised against continuing <strong>the</strong>ir pregnancy. In cultureswhere women’s value is strongly linked to <strong>the</strong>ir maternalabilities and where childbearing brings social status andeconomic support, stigmas arise around a woman’s realor perceived infertility. (See Chapter 3 for morediscussion on sexual and reproductive health and rightsin relation to HIV prevention).Choices around childbearing may be most acute foryoung, married women living with HIV and AIDS. On <strong>the</strong>one hand, women who choose not to have children orto stop childbearing before having <strong>the</strong> socially expectednumber of children, may be stigmatised for breakingsocial and gender norms. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand,communities frown upon women living with HIV andAIDS having children, and tend to blame <strong>the</strong>m forinfecting <strong>the</strong>ir children. “In India, mo<strong>the</strong>rhood isperceived as <strong>the</strong> ultimate validation of womanhood.With <strong>the</strong> increasing risk of married, monogamouswomen contracting HIV… women [are commonly]stigmatised and blamed for passing <strong>the</strong> infection to herunborn child. Blame is accentuated if a male babybecomes infected, due to <strong>the</strong> high value alreadyawarded male children.” 24HIV-positive mo<strong>the</strong>rs also may need to take precautionsto prevent mo<strong>the</strong>r-to-child transmission, such as usingbreast milk substitutes. However, in cultures wherebreastfeeding is commonplace, women who don’tbreastfeed may be condemned by relatives or o<strong>the</strong>rmembers of <strong>the</strong> community. Failure to breastfeed is oftenseen as tantamount to an admission of HIV-positivestatus. Even women aware of <strong>the</strong> risks of breastfeedingmay continue <strong>the</strong> practice because of <strong>the</strong> fear of beingstigmatised or because of economic dependence onhusbands who can’t or won’t give <strong>the</strong>m money forformula. Stuck between contradictory culturalexpectations, <strong>the</strong>se young women can be said to face‘multiple, simultaneous stigma’ 25 (see Chapter 3 for moreon prevention of mo<strong>the</strong>r-to-child transmission plus).<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 15

2.2. Right to <strong>the</strong> highest attainable standardof health“When my husband was ill I went with myhusband for medication, but when I’m illI talk to <strong>the</strong> NGO staff.” 26Woman respondent, <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk research,Pakistan, 2007Many women and girls living with HIV and AIDS,especially those who live in poor, rural communities, findit difficult to take care of <strong>the</strong>ir health. In some cases<strong>the</strong>y face discrimination from health professionals thatfur<strong>the</strong>r violates <strong>the</strong>ir rights. As one woman in Nepalreported, “When I visited Teku Hospital for getting myquota of ARV for that month, <strong>the</strong>re was a new nurse<strong>the</strong>re. When I asked her for ARV, she looked at me fromtop to bottom and made a comment ‘you look sopretty, you must have been involved in some immoralbehaviour, that’s why you got this virus’.” 27 Suchdiscrimination and stigma, coupled with inadequatetraining around HIV and AIDS, has resulted in somewomen receiving poor treatment or inaccurateinformation from health professionals in comparison tothat given to men:“A man gets priority treatment with politenessfrom <strong>the</strong> nurses while a woman in pain screamsin <strong>the</strong> background. A woman is also most of <strong>the</strong>time shouted at and dismissed easily when <strong>the</strong>yare late for medication. If <strong>the</strong> medication is notavailable <strong>the</strong>y are told to go home, notconsidering <strong>the</strong> distance that <strong>the</strong>y have travelledto get <strong>the</strong>re.” 28The International Community of Women Living with HIVand AIDS (ICW) has highlighted many incidents ofwomen living with HIV and AIDS who have beenadvised to have terminations or sterilisations, have beengiven misinformation about child-bearing options,prevention of parent-to-child transmission andbreastfeeding, or encountered fear or judgement fromhealthcare workers. 29 In research for this report inChina, for example, one focus group participantreported that she had been forced by healthcareprofessionals to have a termination of her pregnancybecause she was living with HIV and AIDS. 30 Researchin Namibia has found that healthcare workers do notmake medical information accessible to <strong>the</strong>ir clients,thus denying <strong>the</strong>ir right to information. Women inNamibia reported that <strong>the</strong>y often do not understandwhat healthcare workers are telling <strong>the</strong>m about <strong>the</strong>irhealth or treatment. 31As a result, many women and girls are reluctant toaccess or return to healthcare facilities. All participantsin one focus group in India, for example, agreed thatwomen and girls find it difficult to visit clinics comparedto men, mainly because of stigma and discrimination,and <strong>the</strong> fear of being branded as sex workers. 32Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, many cases exist of health professionalsviolating women’s right to privacy by notifying o<strong>the</strong>rs of<strong>the</strong>ir HIV status. For example, one woman interviewedby ICW reported <strong>the</strong> following:“I got pregnant and was happy about that. But,after <strong>the</strong> delivery, I got ill. They did a test withoutmy knowledge. And <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> staff didn’t treat meso well. And <strong>the</strong>n, instead of telling me <strong>the</strong> result,<strong>the</strong>y announced it to my husband! No one saidanything about it to me. I had no idea what wasgoing on. People began to treat me strangely, butI didn’t know why. It was only four months laterthat my husband told me I was HIV-positive.” 33According to <strong>the</strong> Positive Women’s Network (PWN+) inIndia, some health systems also fail to provide adequatetreatment for opportunistic infections commonlyaffecting women living with HIV and AIDS. PWN+ foundthat a lack of trained medical staff specialising in <strong>the</strong>seareas has resulted in a dire shortage of medicaldiagnostics, treatment and care for many opportunisticinfections experienced by women. 34 Similarly, despitegrowing evidence that HIV and AIDS predisposeswomen to cervical cancer regardless of age, ICW foundthat many health professionals in South Africa andSwaziland refused to screen women living with HIV andAIDS for cervical cancer, 35 thus violating <strong>the</strong>ir sexual andreproductive rights. As one woman in Sibasa, SouthAfrica reported, “I tested HIV-positive in 2003. To date Ihave not been asked about a pap smear or anything likethat at my clinic.” 36There are also more practical concerns that womenhave. In Bangladesh, for example, one focus groupexpressed concerns that, at one state-owned hospital,women were placed in mixed-sex general wardsregardless of <strong>the</strong>ir ailment, while men with certainailments were placed in men only wards. 37 One focusgroup in India also expressed a wish for health servicesto provide a separate section for women in clinics andhospitals as well as a good attitude to patients, femaledoctors, provision of house visits and provision ofchildcare facilities. 38The burden of unrecognised domestic and informalwork, including caring for o<strong>the</strong>rs (see Chapter 5) meansthat many women are simply not able to find time torealise <strong>the</strong>ir own right to health. The need to make16 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

childcare arrangements or to take time off work mayprevent many women from accessing health clinics,particularly those who work in <strong>the</strong> informal sector wheresick leave and o<strong>the</strong>r employment rights may not exist.Finally, because of costs such as transport to healthfacilities or user fees for accessing medical services,formal medical care may simply not be an option formany women and girls, even for those with a regularincome. Richard Bauer, Chief Executive of CatholicAIDS Action in Namibia, highlighted this tension:“People need to make a decision on ei<strong>the</strong>r buyingfood for <strong>the</strong>ir family or spending money ontransport to access a medical facility. Mostpeople decide to go for <strong>the</strong> short-term solutionand provide food to <strong>the</strong>ir family.” 39Restrictions on freedom of movement fur<strong>the</strong>r mean thatsome women are not allowed to go to <strong>the</strong> doctor aloneor without permission from a male relative. In Malawi,Nigeria, Mali and Burkina Faso, 70% of womensurveyed said <strong>the</strong>ir husbands made <strong>the</strong> decisionsregarding <strong>the</strong>ir healthcare. 40 In rural areas of Limpopoprovince in South Africa, some women we spoke toregard men as <strong>the</strong> head of <strong>the</strong> family and every familymember is expected to follow his words. Women toldresearchers that <strong>the</strong>y find it difficult to seek helpbecause this action alone might lead <strong>the</strong>ir husbandsand <strong>the</strong>ir husbands’ families to suspect she is doingsomething against her husband’s will. Even leaving <strong>the</strong>house of <strong>the</strong>ir own accord may place a woman’smotives under suspicion. In such a situation, it is hardfor women to realise <strong>the</strong>ir health rights by going to aclinic or to seek support for fear of being diagnosed assick and being blamed for her illness. 41The stress and impact of restricted mobility, of <strong>the</strong>financial cost of healthcare, and of <strong>the</strong> time spenttravelling to healthcare facilities is well articulated by onewoman from Nepal, who feared seeking <strong>the</strong> permissionof her parents-in-law to travel to a treatment centre:“This time I said I am going for some check upbut in future when I need to travel repeatedly, Idon’t know what I should say to seek <strong>the</strong>irpermission. Kathmandu is very far from my homeand I can’t bear <strong>the</strong> repeated travelling cost.” 42Indeed, costs and financial considerations are asignificant impediment to universal access, as weexplore in <strong>the</strong> next section.2.3. Poverty and economic rights“If you want me to have sex with a condom,I won’t give you any money for food.” 43Partner of member of Women against Women Abuse,South AfricaPoverty is a major driver of HIV and AIDS. It is alsoinextricably tied to women’s rights, as women make upa majority of <strong>the</strong> world’s poor population. Globally,women are more likely than men to work in <strong>the</strong> informalsector with low earnings, little financial security and fewor no social benefits such as free or subsidised antiretroviraltreatment, or food supplements. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,a woman’s earned income is on average approximatelyhalf that of a man’s in sub-Saharan Africa, falling to 40%in Latin America and South Asia, and 30% in <strong>the</strong> MiddleEast and North Africa. 44Feminised poverty is also linked to women’s lack ofability to administer and own property. Some womenand girls also have limited control over householdincome and assets, despite <strong>the</strong>ir right to own andadminister property. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example,title deeds to land are normally issued to male heads ofhousehold. 45 In Kenya, women hold only 1% ofregistered land titles and around 5-6% of registered titlesare held jointly with o<strong>the</strong>rs. 46 Even upon inheritance,many women and girls face eviction from family propertybecause of disputes with members of <strong>the</strong>ir husband’s orfa<strong>the</strong>r’s extended family. 47 Such property grabbing iscommon as women and girls are thrown off <strong>the</strong>ir land byhusbands/partners and <strong>the</strong>ir relatives.Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, legislation, where adopted, may not givewomen equal protection under <strong>the</strong> law. The Indian HinduSuccession Act 1956, for example, recognised <strong>the</strong> rightof women to inherit <strong>the</strong> property of <strong>the</strong>ir fa<strong>the</strong>r. However,this Act does not apply to women belonging to non-Hindu religious communities and is rarely implementedeven in <strong>the</strong> case of Hindu women. 48 Without propertyand inheritance rights, women and girls living with HIVand AIDS, widowed or abandoned by <strong>the</strong>ir husbands orfamilies, may be left penniless and destitute.Poverty and <strong>the</strong> resulting economic dependency ofmany women and girls often means that <strong>the</strong>y are forcedto rely on, and stay with, <strong>the</strong>ir male partners, even inviolent or abusive relationships. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, it gives<strong>the</strong>m little power to negotiate safe sex, even when <strong>the</strong>yknow that <strong>the</strong>ir partners are HIV-positive or havemultiple sexual relations. In Zimbabwe, for example,“although women knew <strong>the</strong>ir sexual rights, <strong>the</strong>y fear<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 17

imprisonment of <strong>the</strong>ir husbands and <strong>the</strong> consequentloss of income if <strong>the</strong>y reported sexual violence by <strong>the</strong>irpartners.” 49 Early marriage and relationships with ‘sugardaddies’ often represent a form of economic exchangewhich leave women and girls with little power. Insituations of extreme poverty, sex serves as a survivalstrategy, where women balance immediate needs offood or shelter with <strong>the</strong> more distant and abstractprospect of contracting a disease.This same economic dependency forces many womenand girls to disclose <strong>the</strong>ir HIV status and ask <strong>the</strong>ir malepartners or guardians for money for medication ortransport. 50 According to <strong>the</strong> Zimbabwe study, “somewomen living with HIV and AIDS had been deserted by<strong>the</strong>ir husbands,” and “many were facing problems inraising funds for AIDS treatment, including CD4 cellcounting services”. Even when her partner stands byher, such dependency can leave women morevulnerable to interruptions in <strong>the</strong>ir treatment. In Uganda,for example, “if <strong>the</strong> husband dies, most of <strong>the</strong> widowsare dependent and <strong>the</strong>ir lives change so abruptly”. 51In fact, socio-economic barriers are a major reasonwomen are unable to access treatment, care andsupport. In many countries, prohibitively high hospitalfees combined with o<strong>the</strong>r expenses are a major barrierto access. According to research in Nepal undertakenfor this report, “The major obstacles faced by <strong>the</strong>sewomen… are associated with regular cost toKathmandu, and to clinics for CD4 count and ARTcoupled with <strong>the</strong> time lost due to long travel time andfew days stay in Kathmandu and thus time lost fromregular income generation work and childcare.” 52The burden of HIV and AIDS care places a heavy tollon women and girls, affecting <strong>the</strong>ir financialproductivity, among o<strong>the</strong>r things. Up to 90% of care isprovided in <strong>the</strong> home, and <strong>the</strong> principal givers ofphysical and psychosocial support are women andgirls. 53 In one region in Ethiopia, for example, about85% of care providers (<strong>the</strong> majority of whom arewomen) spend <strong>the</strong>ir time providing care and supportto home-based patients and have no o<strong>the</strong>r sources ofincome to support <strong>the</strong>ir families. 54 It is often taken forgranted that such women will continue to provideunremunerated care and support to infected andaffected family and community members. Lesserknown is <strong>the</strong> cost of this care, how it affectseconomic, societal and familial relations, and – last butnot least – <strong>the</strong> women and girls <strong>the</strong>mselves (seeChapter 5).2.4. Recommendations Donor governments1) Donor governments should consult with women’smovements, local networks and movements ofwomen living with HIV and AIDS to ensure donorfunding reflects local priorities of <strong>the</strong> people livingwith and affected by HIV and AIDS. They shouldalso ensure that <strong>the</strong>ir policies and programmes donot reinforce inequalities.2) Donor governments should fund civil society andlegal aid organisations to support women living withHIV and AIDS to establish test cases, research,monitor and report women’s rights violations, andto lobby and advocate for reform of laws andpolicies that discriminate against women.3) Donor governments should ensure long-term,predictable funding for <strong>the</strong> streng<strong>the</strong>ning of healthsystems, in particular to ensure women-friendlyhealth systems that integrate HIV and sexual andreproductive health rights (SRHR) services.18 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

Multilateral organisations1) The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS(UNAIDS) and <strong>the</strong> World Health Organizationshould develop clear guidelines and a strategy tosupport country governments to develop a humanrights-based analysis of <strong>the</strong> barriers faced bywomen and girls for scaling up HIV and AIDSaction. This can be done in conjunction with localHuman Rights Commissions.2) The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis andMalaria should improve expertise on women’srights at all levels of <strong>the</strong> decision-making processand develop adequate indicators to ensure thatcountry coordinating mechanisms are reflecting <strong>the</strong>priorities and rights of women and girls.3) The second independent evaluation of UNAIDSmust analyse <strong>the</strong> degree to which women's rightsin relation to HIV and AIDS are addressed byUNAIDS and its co-sponsors. It must make clearrecommendations around women's rights toimprove UNAIDS’ effectiveness.Developing country governments1) National governments should base national HIVand AIDS strategies on a human rights-basedanalysis of <strong>the</strong> barriers faced by women and girls inregard to HIV prevention, treatment, care andsupport services. This should have <strong>the</strong> participationof women and girls, living with and affected by HIVand AIDS, at its heart.2) National governments should tackle stigma anddiscrimination head on by establishing andenforcing anti-discrimination laws, investing innational stigma reduction campaigns and byproviding training for doctors and healthcareworkers on <strong>the</strong> rights of women and girls living withHIV and AIDS. Governments, donors and civilsociety should also be careful about how publicinformation campaigns transmit messages in orderto avoid stigmatising messages.3) National governments should provide training andfunding and put systems in place to ensure thatadequate staffing, diagnostics, medicines and o<strong>the</strong>rprovisions are made to treat opportunisticinfections that particularly affect women and girls,such as cervical cancer. Governments must investin training female healthcare workers and o<strong>the</strong>rmedical professionals.Civil society organisations1) Civil society should prioritise capacity building inwomen’s rights-based programming in <strong>the</strong>ir HIVand AIDS responses.2) Civil society organisations in developed anddeveloping countries should prioritise women’srights advocacy and campaigns at all levels.3) Civil society should ensure that a human rightsapproach to <strong>the</strong> barriers faced by women and girlsis at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong>ir programmatic interventions.<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 19

Gideon Mendel/Corbis/ActionAidYoung people march in a street protest against analleged child abuser in <strong>the</strong> poor Lagos neighbourhoodof Ajeromi, Nigeria.3. Women’s rights anduniversal access toHIV preventionThe political declaration on HIV/AIDS adopted by <strong>the</strong>UN General Assembly in 2006 reaffirmed <strong>the</strong> centralityof women’s rights in HIV prevention. 55 Governmentspledged “to eliminate gender inequalities, gender-basedabuse and violence; increase <strong>the</strong> capacity of womenand adolescent girls to protect <strong>the</strong>mselves from <strong>the</strong> riskof HIV infection.” 56Such ambitious goals necessitate multi-prongedstrategies. Whereas critical areas of HIV prevention havealready been explored in Chapter 2, including issuesaround sexual and reproductive rights and violenceagainst women, this chapter examines a variety ofcomplementary strategies to empower women (and men)to protect <strong>the</strong>mselves against contracting HIV. Thesestrategies can be roughly divided into <strong>the</strong> categories of‘information’, including formal and informal education andawareness-raising to promote behaviour change;‘technologies’ and medical interventions, includingcondoms, microbicides, circumcision, and post-exposureprophylaxis; and services such as voluntary counselling20 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

and testing. A few of <strong>the</strong> strategies, such as prevention ofmo<strong>the</strong>r-to-child transmission plus, can be consideredcross-cutting, as <strong>the</strong>y involve elements of all of <strong>the</strong>sestrategies. No strategy will succeed if tackling genderinequality and women’s lack of power to use HIVprevention is not at its heart.3.1. Women’s right to education and informationSexuality education in schoolsIn <strong>the</strong> absence of a cure for HIV and AIDS, educationhas been called a ‘social vaccine’ for preventing HIV.Research in a variety of settings asserts that educatedgirls are more likely to know <strong>the</strong> basic facts about HIVand AIDS, more empowered to negotiate safe sex, maybe more likely to delay sexual activity, and are less likelyto suffer from sexual and gender-based violence. 57Women with at least a primary education are threetimes more likely than uneducated women to know thatHIV can be transmitted from mo<strong>the</strong>r to child. 58Schools play a crucial role in providing vital informationon HIV prevention. They are often <strong>the</strong> only method fordelivering information on HIV prevention, especially inremote places, or where access to family planninginformation only exists for married couples, such as inVanuatu. Recent statistics make it clear that youngpeople need better access to accurate information onsafer sex. According to UNAIDS, “though <strong>the</strong>Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS aimed for 90%of young people to be knowledgeable about HIV by2005, surveys indicate that fewer than 50% of youngpeople achieved comprehensive knowledge levels.” 59 InZimbabwe, adolescents associated with this study“showed ignorance of sexual and reproductive rights”as well as negative perceptions about condoms which<strong>the</strong>y associate with lack of trust among partners. 60 InVanuatu, girls openly said that <strong>the</strong>y were afraid to ask touse condoms “in case <strong>the</strong>y were accused of beingpromiscuous” and showed a clear lack of knowledgeand familiarity with <strong>the</strong>ir bodies when acknowledging<strong>the</strong>ir anxiety to use condoms for fear that “<strong>the</strong>y wouldget stuck”. 61Education also plays a second, crucial role in“empowering young women to take control of <strong>the</strong>irsexual lives.” 62 Studies have shown, for example, that“completion of secondary education was related tolower HIV risk, more condom use and fewer sexualpartners, compared to completion of primaryeducation”. 63 We also know young people are morelikely to delay sexual activity if <strong>the</strong>y receive correct andunbiased information, allowing <strong>the</strong>m to make informeddecisions. 64 For example, highly educated girls andwomen are better able to negotiate safer sex, having animpact on HIV rates. 65 Given <strong>the</strong> predominance ofpressure to enter into high-risk sex, this is especiallyimportant. In research completed in Nigeria, SouthAfrica and Vanuatu, boys were generally quoted aswanting to have ‘skin to skin’ sex. 66 In South Africa, forexample, HIV prevention strategies involving life-skillsprogrammes focusing on HIV and AIDS in schools werefound to be “not appropriate for women who are poorand vulnerable to violence” because <strong>the</strong>y do not “digdeep into <strong>the</strong> dynamics of gender inequality and armyoung women and men to transform <strong>the</strong> cycle ofinequality and gender-based violence in society.” 67Taught properly, sexuality education can begin tochange harmful gender stereotypes and empower boysand girls to make choices about healthy sexualbehaviours, including protecting <strong>the</strong>mselves from HIV.Information given must be comprehensive and evidencebased, and lessons must go beyond presentingbiological facts to providing a space for girls and boysto discuss, challenge and analyse gender relations. Thisshould include gender equality, girls’ empowerment,mutual respect, gender-awareness education for boysand girls, and empowerment training for girls.Information should be fully integrated in school curriculain consultation with <strong>the</strong> community, local leaders andgatekeepers. An example of good practice is <strong>the</strong> newcurriculum developed last year in Nigeria forcomprehensive sex education targeting 10-18 year olds.It aims to increase <strong>the</strong>ir knowledge and change <strong>the</strong>irattitudes to sexual health and reduce risky behaviours.In <strong>the</strong> past such measures would have faced strongopposition on religious and cultural grounds, but thistime <strong>the</strong> curriculum was developed in consultation withreligious and community leaders, showing promisingsigns for long-term implementation. 68To enable effective sexuality education, governmentsmust invest in girls’ education to send <strong>the</strong> strong signalthat <strong>the</strong>ir education is just as important as that of boys.Although, worldwide, girls’ enrolment has gone up,gender inequality in accessing education remains animportant issue, 69 in particular in sub-Saharan Africa. 70The efforts must be sustained at all levels of educationsince gender inequality in accessing secondaryeducation stems from disparities in primary education. 71In Vanuatu, as in many countries surveyed, “boys in <strong>the</strong>family get priority if resources are limited.” Educatinggirls was seen as a “waste of resources if you just wan<strong>the</strong>r to stay home,” since “educating women mightencourage <strong>the</strong>m to look outside <strong>the</strong> home”. 73 Thisshows that family and marriage are still often wrongly<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 21

perceived as safe havens for girls whose worth isstill exclusively tied to <strong>the</strong>ir roles as mo<strong>the</strong>r andcare provider.In order to maximise <strong>the</strong> educational benefit ofschooling and to promote girls’ safety andempowerment, girls must be free from violence in <strong>the</strong>school setting. 74 Growing evidence of sexual violenceand exploitation in schools shows that girls (and lessoften boys) experience rape, assault and sexualharassment both by teachers and male students. Insome countries, it is considered an inevitable part of <strong>the</strong>school environment. 75 Research in Ghana, Malawi andZimbabwe demonstrates <strong>the</strong> role of schools <strong>the</strong>mselvesin sanctioning sexual and gender-based violence. 76According to <strong>the</strong> study, this includes male teachers andpupils propositioning girls for sex, teachers andstudents using language sexually explicit and degradingfor girls; and teachers dismissing boys’ intimidatingbehaviour as a normal part of ‘growing up’. Violenceand fear of violence are important reasons for girls notattending school. In fact, many cases go unreportedbecause of fear of stigmatisation by <strong>the</strong> family orbroader community. 77 As long as <strong>the</strong> state, officials, <strong>the</strong>police and prosecutors pass <strong>the</strong> responsibility to eacho<strong>the</strong>r, leaving perpetrators unpunished, girls’ right tobodily integrity will keep being violated. 78Women’s rights and awareness-raising: fromawareness to behaviour changeIn some rural areas, state-sponsored health oreducation services are not available. The existence ofaccessible, reliable information in <strong>the</strong>se areas isespecially important because of high levels of ignoranceand misinformation about HIV and AIDS. In Nepal, forexample, “<strong>the</strong> rural female, though classified as a lowrisk population, is in fact at extreme high risk due to adeeply rooted traditional discrimination belief systemthat regards <strong>the</strong> discussion of HIV and AIDS as beingtaboo, <strong>the</strong>ir traditionally lower, unequal social status andlimited access to means of protection rendering <strong>the</strong>mvulnerable to infection.” 80In such circumstances it is often civil society thatprovides information about how to prevent HIV andAIDS. In o<strong>the</strong>r rural areas where health and educationservices are available but limited, civil society plays acrucial role in disseminating information on HIVprevention. For example, one woman in <strong>the</strong> ruralprovince of Limpopo, one of <strong>the</strong> poorest regions inSouth Africa, said:“Without <strong>the</strong> NGOs, we would have very littleinformation. Indeed, many of us would just die ofignorance.” 81Efforts to raise awareness in rural areas about HIVprevention must <strong>the</strong>refore be increased through nationaland local campaigns. A rights-based approach to publicawareness-raising campaigns on HIV preventionrequires key messages to be tailored for women andgirls. As one focus group participant in Nigeria said:“Women and girls need prevention messagestailored peculiarly to <strong>the</strong> needs of women, <strong>the</strong> useof such messages on men worked for familyplanning and <strong>the</strong> same can be used to tell womenthat using [a] condom is also <strong>the</strong>ir right.” 82For example, information must be available in locallanguages in order to ensure that women have access to<strong>the</strong> information <strong>the</strong>y need to make informed HIVpreventionchoices. Local clinics should have up-to-datematerials displayed on <strong>the</strong> walls or available for patients totake away. Information must also be made availablethrough multiple means in order to increase itsaccessibility, for example to illiterate women and girls. Onefocus group in India suggested street <strong>the</strong>atre should beused to target unique locations frequented by women,such as markets, places of worship and primaryschools. 83 In Nigeria, women and girls cited radiocampaigns and <strong>the</strong> engagement of celebrities andBox 1. Female guardians (mlezi), TanzaniaA good practice in this area comes from Tanzania, which instituted a ‘female guardian’ programme in primaryschools. This initiative trains guardians or mlezi, one per primary school, to give advice in cases of sexual violenceor harassment and o<strong>the</strong>r issues related to sexual health and HIV and AIDS. The programme began as an HIVpreventioneffort when girls identified sexual coercion as a major issue affecting prevention efforts. Mlezi areteachers chosen by <strong>the</strong>ir colleagues and trained to give advice and advocate for girls in cases of wrongdoing. Anevaluation of <strong>the</strong> programme has shown that <strong>the</strong> establishment of mlezi has significantly increased <strong>the</strong> reportingof sexual harassment or violence in <strong>the</strong> schools. 7922 <strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response

Box 2. The Climbing to Manhood Project, Chogoria hospital, KenyaIn Kenya, <strong>the</strong> Climbing to Manhood Project of Chogoria hospital uses <strong>the</strong> practice of circumcision, a traditionalrite of passage, to address issues around young men’s sense of manhood and masculinity. During <strong>the</strong> time ofcircumcision around <strong>the</strong> age of 15, boys are expected to undergo physical, psychological and behaviouralchanges associated with manhood, and may be encouraged to begin having sexual relations. Chogoria hospitalrecognised <strong>the</strong> time around this ceremony as an opportunity to inform boys about sexual health. Incorporating<strong>the</strong> seclusion and bonding that occur as part of traditional circumcision rites, groups of boys participating in <strong>the</strong>project spend a week toge<strong>the</strong>r in a special ward following hospital circumcision. Men from <strong>the</strong> communityincluding healthcare workers, pastors and teachers explore a range of topics with <strong>the</strong>m including STIs and HIVand AIDS, community expectations of men, and issues surrounding violence. 92musicians as good sources of HIV-prevention messages. 84In South Africa, women mentioned Soul City and Lovelife,TV programmes that have been targeting youth with HIVpreventioninformation. Soul City has in fact been verysuccessful in its outreach and replication in o<strong>the</strong>r countriesof <strong>the</strong> region, including <strong>the</strong> creation of school clubs.International donors, including DFID, fund <strong>the</strong> project andit provides a clear case of good practice. Governmentsand donors should fund additional and large-scaleprogrammes that raise awareness of HIV prevention with<strong>the</strong> participation of women and girls. These campaignsmust go hand in hand with programmes challenginggender norms so that women and girls’ knowledge aboutHIV and AIDS is accompanied by <strong>the</strong> necessary power tonegotiate safer sex.Public campaigns must also reflect women’s rights, <strong>the</strong>need for women’s empowerment and women’sleadership in order to be effective. The ABHAYA projectin India, for example, raises awareness amongvulnerable and excluded groups of <strong>the</strong>ir rights andentitlements. The project has had substantial successbasing HIV-prevention messages on women’s rights. Asone sex worker explained:“Here I learnt that if we sex workers unite, we willbe able to get our rights. We talked aboutviolence and how we can protect ourselves fromviolence, and that we have <strong>the</strong> right to askquestions. I come to ABHAYA for <strong>the</strong> monthlysupport group meetings and visit <strong>the</strong> STI clinicregularly. I have also learnt about safe sex andHIV and AIDS after coming here and have startedinsisting on using condoms ever since.” 85However, among <strong>the</strong> women interviewed for thisresearch, this experience seems to be <strong>the</strong> exceptionra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> rule. Many women and girls remainunaware of <strong>the</strong>ir rights. Some members of a focusgroup of women living with HIV and AIDS inBangladesh, for example, argued that women are“usually unaware of <strong>the</strong>ir basic rights”. 86 For o<strong>the</strong>rrespondents, women seemed to be “programmed froman early age to think of <strong>the</strong>mselves as unequal and thus<strong>the</strong>y are not aware of <strong>the</strong>ir rights as individuals”. 87Finally, women and girls’ access to HIV preventioninformation and services often lies in <strong>the</strong> hands ofhusbands, fa<strong>the</strong>rs, community leaders and serviceproviders who play <strong>the</strong> role of gatekeepers. For example,women and girls are often deliberately left in <strong>the</strong> darkregarding <strong>the</strong>ir husband’s HIV status as well as <strong>the</strong>ir own.One focus group in Bangladesh reported cases of womenwhose husbands had infected <strong>the</strong>m knowingly andsubsequently refused <strong>the</strong>m or <strong>the</strong>ir children an HIV test. 88“When a male is identified as positive, it oftentakes considerable convincing and coercing for<strong>the</strong>m to get <strong>the</strong>ir families tested” [and <strong>the</strong>husband] “always makes that decision.” 89To resolve this, one focus group participant in Nigeriaemphasised that:“Messages should be made in such a way that<strong>the</strong>y give power to women to freely makechoice[s] and take decisions on usage ofprevention tools like condom[s].” 90In particular, community awareness-raising initiativesneed to be long-term, strategic and sustainable. 91 Theyneed to enable women to increase <strong>the</strong>ir participation,power and equality in <strong>the</strong> community and familyspheres, lead men to act responsibly and respect <strong>the</strong>irwives’ rights, and enable women and girls to share<strong>the</strong>ir positive status publicly without violence, stigmaand discrimination.<strong>Walking</strong> <strong>the</strong> talk putting women's rights at <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong> HIV and AIDS response 23