Dressings can prevent pressure ulcers: fact or fallacy? - Wounds ...

Dressings can prevent pressure ulcers: fact or fallacy? - Wounds ...

Dressings can prevent pressure ulcers: fact or fallacy? - Wounds ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

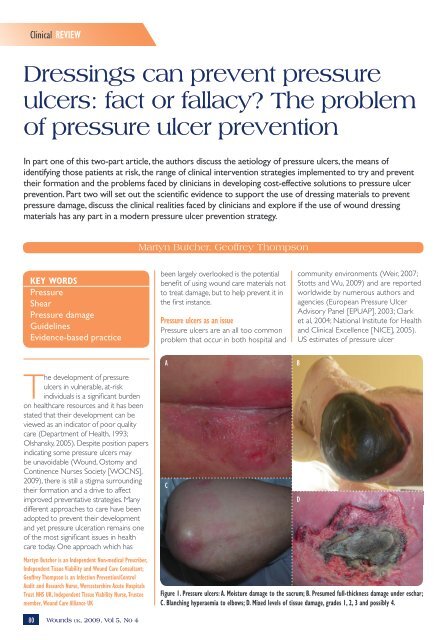

Clinical REVIEW<strong>Dressings</strong> <strong>can</strong> <strong>prevent</strong> <strong>pressure</strong><strong>ulcers</strong>: <strong>fact</strong> <strong>or</strong> <strong>fallacy</strong>? The problemof <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer <strong>prevent</strong>ionIn part one of this two-part article, the auth<strong>or</strong>s discuss the aetiology of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>, the means ofidentifying those patients at risk, the range of clinical intervention strategies implemented to try and <strong>prevent</strong>their f<strong>or</strong>mation and the problems faced by clinicians in developing cost-effective solutions to <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer<strong>prevent</strong>ion. Part two will set out the scientific evidence to supp<strong>or</strong>t the use of dressing materials to <strong>prevent</strong><strong>pressure</strong> damage, discuss the clinical realities faced by clinicians and expl<strong>or</strong>e if the use of wound dressingmaterials has any part in a modern <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer <strong>prevent</strong>ion strategy.Martyn Butcher, Geoffrey ThompsonKEY WORDSPressureShearPressure damageGuidelinesEvidence-based practicebeen largely overlooked is the potentialbenefit of using wound care materials notto treat damage, but to help <strong>prevent</strong> it inthe first instance.Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong> as an issuePressure <strong>ulcers</strong> are an all too commonproblem that occur in both hospital andcommunity environments (Weir, 2007;Stotts and Wu, 2009) and are rep<strong>or</strong>tedw<strong>or</strong>ldwide by numerous auth<strong>or</strong>s andagencies (European Pressure UlcerAdvis<strong>or</strong>y Panel [EPUAP], 2003; Clarket al, 2004; National Institute f<strong>or</strong> Healthand Clinical Excellence [NICE], 2005).US estimates of <strong>pressure</strong> ulcerThe development of <strong>pressure</strong><strong>ulcers</strong> in vulnerable, at-riskindividuals is a signifi<strong>can</strong>t burdenon healthcare resources and it has beenstated that their development <strong>can</strong> beviewed as an indicat<strong>or</strong> of po<strong>or</strong> qualitycare (Department of Health, 1993;Olshansky, 2005). Despite position papersindicating some <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> maybe unavoidable (Wound, Ostomy andContinence Nurses Society [WOCNS],2009), there is still a stigma surroundingtheir f<strong>or</strong>mation and a drive to affectimproved <strong>prevent</strong>ative strategies. Manydifferent approaches to care have beenadopted to <strong>prevent</strong> their developmentand yet <strong>pressure</strong> ulceration remains oneof the most signifi<strong>can</strong>t issues in healthcare today. One approach which hasMartyn Butcher is an Independent Non-medical Prescriber,Independent Tissue Viability and Wound Care Consultant;Geoffrey Thompson is an Infection Prevention/ControlAudit and Research Nurse, W<strong>or</strong>cestershire Acute HospitalsTrust NHS UK, Independent Tissue Viability Nurse, Trusteemember, Wound Care Alliance UKACFigure 1. Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong>: A. Moisture damage to the sacrum; B. Presumed full-thickness damage under eschar;C. Blanching hyperaemia to elbows; D. Mixed levels of tissue damage, grades 1, 2, 3 and possibly 4.BD80<strong>Wounds</strong> uk, 2009, Vol 5, No 4

Clinical REVIEW8 Pressure duration over the <strong>pressure</strong>points which <strong>can</strong> result in damagefrom high <strong>pressure</strong> f<strong>or</strong> sh<strong>or</strong>t intenseperiods, which <strong>can</strong> be as damaging aslow <strong>pressure</strong> f<strong>or</strong> prolonged periods(Bell, 2005)8 Collagen function protecting themicrocirculation helps to maintainthe <strong>pressure</strong>s inside and outsidethe cells <strong>prevent</strong>ing cell bursting.Collagen levels vary from personto person with lessening protectivequalities with aging (Russell, 1998)8 Aut<strong>or</strong>egulat<strong>or</strong>y processes initiatedwhen external <strong>pressure</strong> is sensed,leading to increased internal capillary<strong>pressure</strong>, reduced blood flow andreactive hyperaemia to counteractthe <strong>pressure</strong> loading.These mechanisms <strong>can</strong> fail when theexternal <strong>pressure</strong> exceeds the person’sdiastolic <strong>pressure</strong> rather than the32mmHg often quoted (Nixon, 2001).The response of tissue to externalf<strong>or</strong>ces varies greatly, being dependenton a large number of <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s. It istheref<strong>or</strong>e not possible to establish a‘safe level of <strong>pressure</strong>’. In addition,tolerance to <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>can</strong> vary greatlyfrom individual to individual due tothe interplay of external <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s listedin Table 1. Given the highly variablenature of <strong>pressure</strong> transmission, capillaryclosure and the individual’s n<strong>or</strong>mal andadaptive responses to <strong>pressure</strong> stress,the production of time/<strong>pressure</strong> curves(mathematical models f<strong>or</strong> predicting thetime likely to cause tissue damage whentissue is exposed to specific levels of<strong>pressure</strong> [Reswick and Rogers, 1976])may be of little practical benefit to theclinician in everyday practice (Sharp andMcLaws, 2005; Grefen, 2009).Shear is a mechanical stress appliedparallel to the skin. The SFI describes itas: ‘An action <strong>or</strong> stress resulting fromapplied f<strong>or</strong>ces which causes <strong>or</strong> tends tocause two contiguous internal parts ofthe body to def<strong>or</strong>m in the transverseplane (i.e. “shear strain”)’ (SFI, 2006).This sliding <strong>or</strong> twisting f<strong>or</strong>ce occurscontinuously within soft tissues evenwhen perpendicular <strong>pressure</strong> is applied,but increases greatly when combinedwith lateral movement, as seen when84 <strong>Wounds</strong> uk, 2009, Vol 5, No 4the body is adapting to the inclinationof the bed <strong>or</strong> when sitting in a chair. Ifthe skin adheres to the surface supp<strong>or</strong>t(which is m<strong>or</strong>e likely if the skin is moist<strong>or</strong> wet from environmental <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s<strong>or</strong> intrinsically from incontinence <strong>or</strong>sweating) (Weir, 2007; Beldon, 2008), thetissues attached to the gradually movingskeletal frame become dist<strong>or</strong>ted which,in turn, dist<strong>or</strong>t the blood vessels leadingto their collapse <strong>or</strong> rupture.Shear f<strong>or</strong>ces are generated as aresult of the interplay of friction and<strong>pressure</strong> (Collier and Mo<strong>or</strong>e, 2006).When applied, shear increases theeffects of <strong>pressure</strong> resulting in vascularocclusion at only half the <strong>pressure</strong> ofnon-stressed tissues (Bennett and Lee,1986). Shear f<strong>or</strong>ces may also have asignifi<strong>can</strong>t role in the development ofdeep tissue damage, although this isdifficult to measure in the clinical setting(Russell, 1998). Potentially, shearing isthe most serious extrinsic risk <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>due to the rapidity with which it <strong>can</strong>result in tissue damage (Sharp andMcLaws, 2005). This is m<strong>or</strong>e likely tooccur in the elderly as a result of loose,fragile skin and the ease with which thedifferent tissue types <strong>can</strong> be sheared offtheir respective attachments (Allman etal, 1995).The edges of <strong>ulcers</strong> caused by shearf<strong>or</strong>ces appear to be ragged with m<strong>or</strong>euneven wound margins, often withsurrounding epidermal scuffing. Bruisingmay also be a feature (Figure 4).The mechanisms of shear damagehave imp<strong>or</strong>tant consequences f<strong>or</strong> theplanning and delivery of <strong>prevent</strong>ativecare interventions, even though thereare few clinical methods to estimateshearing f<strong>or</strong>ces <strong>or</strong> their resultant effectson tissues (Verluysen, 1985). It is hopedthat the w<strong>or</strong>k of the SFI will add to thisbody of knowledge.Friction is a complex phenomenonwhich depends on complex physicalscience and engineering concepts. Insimplistic terms, within the context offriction-induced tissue damage, we arereferring to kinetic friction. Kinetic (<strong>or</strong>dynamic) friction occurs when twoobjects are moving relative to eachFigure 3. Sacral area showing clinical features ofblanching hyperaemia.Figure 4. Shear <strong>pressure</strong> damage occurring in ayoung woman during childbirth.other and rub together. Bergman-Evanset al (1994) define it as the resistanceto lateral movement. Kinetic friction isdependent on mass, f<strong>or</strong>ce applied andthe friction co-efficients of the surfacesinvolved. Clinically, the effect of frictionbetween the skin and a supp<strong>or</strong>t surfacehas imp<strong>or</strong>tant dynamics that <strong>can</strong> initiate<strong>pressure</strong> ulcer f<strong>or</strong>mation:8 It <strong>can</strong> cause excessive wear to thec<strong>or</strong>nified layers of the skin withresultant exposure of the underlyingstructures (Read, 2001)8 It <strong>can</strong> cause the f<strong>or</strong>mation of blistersas separation occurs between thelayers of the epidermis leading to

Wound Clinical care REVIEW SCIENCEexposure of the underlying dermis(Butcher, 1999)8 The def<strong>or</strong>mation of skin <strong>can</strong> leadto further def<strong>or</strong>mation in deepertissues (shear damage).The amount of damage causeddepends on tissue resistance andthe interplay of friction and <strong>pressure</strong>.Pressure and friction together causem<strong>or</strong>e damage than friction alone and willinduce greater shear f<strong>or</strong>ces (Figure 5).MoistureAlthough not directly indicated asa mechanism of <strong>pressure</strong> damage,the role of moisture is pivotal in thedevelopment of friction damage andso is a secondary <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong> in shear f<strong>or</strong>ces(Beldon, 2008) (Figure 6). Moisturelevels within the cells of the epidermishave a direct bearing on the frictionco-efficient of this tissue. Even atrelatively low levels, moisture causes arise in friction co-efficient making skin‘stick’ to surfaces (Nacht et al, 1981). Inaddition, when exposed to moisture f<strong>or</strong>prolonged periods, the keratinised cellsof the epidermis swell and becomewaterlogged. This reduces their abilityto withstand friction and <strong>can</strong> result inepidermal stripping.These features have new relevancesince the re-classification of moisturelesions (Bethell, 2003; Butcher, 2005;Beldon, 2008). There is a closeassociation between incontinencedermatitis, moisture-induced damageand superficial <strong>pressure</strong> ulceration. TheEPUAP have suggested that moistureinduceddamage should be categ<strong>or</strong>isedseparately from <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. Inpractice, this differentiation <strong>can</strong> bedifficult to interpret clinically. Deflo<strong>or</strong>and Schoonhoven (2004) and Deflo<strong>or</strong>et al (2005) identified that reliabilityof the EPUAP tool was low whenused to differentiate moisture lesionsand superficial <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> fromphotographic evidence. Indeed, writerssuch as Houwing et al (2007) argue thatsuch a distinction should not be madeas it distracts clinicians from the needto implement appropriate <strong>pressure</strong>ulcer <strong>prevent</strong>ion strategies, and, asMcDonagh (2008) points out, these twophenomena <strong>can</strong> co-exist within a clientat a given point in time.Aetiological pathwaysControversy exists as to the aetiologicalroute by which <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> f<strong>or</strong>mand progress. It is acknowledged that<strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> are primarily causedby sustained mechanical loading,however, <strong>prevent</strong>ion of ulcer f<strong>or</strong>mationby reducing the degree of loadingalone remains difficult to achieve. Thisis mainly due to po<strong>or</strong> understandingof the underlying pathways wherebymechanical loading leads to tissuebreakdown (Bouten et al, 2005).Three the<strong>or</strong>ies have been postulatedto explain this process:1. Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong> f<strong>or</strong>m via the topto-bottommodel2. Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong> f<strong>or</strong>m via the bottomto-topmodel3. Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong> f<strong>or</strong>m via a middleapproach model.The<strong>or</strong>y 1Pressure and shear induce localischaemia, and impaired drainageimpairs the transp<strong>or</strong>t of oxygen andnutrients to and metabolic wasteproducts away from the cells within theaffected tissues. Eventually this leadsto cell necrosis and the f<strong>or</strong>mation ofan ulcer. There are sound argumentsf<strong>or</strong> damage to muscle tissue as it ismetabolically m<strong>or</strong>e active than skin.The<strong>or</strong>y 2This model states that when <strong>pressure</strong>is relieved from the compressed tissuesby patient repositioning <strong>or</strong> the useof an alternating <strong>pressure</strong>-alleviatingmattress (APAM), it is the rest<strong>or</strong>ationof blood flow after the load-removalrather than impaired blood flow during<strong>pressure</strong> loading that is the mechanismof tissue necrosis. It is claimed that it isan over-abundant release of oxygenfreeradicals during <strong>pressure</strong> off-loadingthat causes the damage.The<strong>or</strong>y 3In the third model, tissue damage maystart anywhere between the skin andthe underlying bone, but <strong>can</strong> includethe skin surface and bone interface,concurrently <strong>or</strong> haphazardly, to producea <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer.Prevalence and incidence of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>Unless c<strong>or</strong>rectly identified and treated,<strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> <strong>can</strong> have a signifi<strong>can</strong>teffect upon the patient’s quality of lifeFigure 5. Shear and friction damage to stump from badly fitting prosthesis.Figure 6. Sacral region showing clinical features ofmoisture damage combined with shear and <strong>pressure</strong>.86 <strong>Wounds</strong> uk, 2009, Vol 5, No 4

Clinical REVIEWand may, under certain circumstances,prove fatal. The deaths of thousandsof patients are attributed to <strong>pressure</strong><strong>ulcers</strong> and their complications everyyear (Agam and Gefen, 2007). Datarelating to incidence (a statisticalmeasurement of the number ofindividuals developing a condition) and<strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> varies considerably. Arecent literature review investigated<strong>pressure</strong> ulcer prevalence and incidencein intensive care patients. The analysis ofdata from published papers highlightedthese variations with <strong>pressure</strong> ulcerprevalence (the number of individualswith <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> as a percentageof the total defined population at onepoint in time) in intensive care settings,ranging from 4% in Denmark to 49% inGermany, while incidence ranged from38% to 124% (Shahin et al, 2008). Ina Canadian study in 2004 the nationalprevalence figure across all care settingswas estimated at 26% (Woodbury andHoughton, 2004). M<strong>or</strong>e specifically,a recent study has shown that theprevalence of <strong>pressure</strong> ulcerationwithin the population receiving healthcare in Bradf<strong>or</strong>d, UK was 0.74 peoplewith a <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer per 1000population (95%, CI 0.6–0.8) (Vowdenand Vowden, 2009).Cost of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> to health carePatients with <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> place aburden on health care as they require asignifi<strong>can</strong>t amount of medical resourcesto treat. A recent survey evaluatedthe impact of wound care in Bradf<strong>or</strong>dand Airedale NHS Primary Care Trustin the UK (Vowden et al, 2009), andshowed that the prevalence of patientswith a wound was 3.55 per 1000population. The estimated cost to theUS hospital sect<strong>or</strong> is $11 billion perannum (Bales and Padwojski, 2009). Thishas been considered unsustainable andunacceptable. In an eff<strong>or</strong>t to controlcosts and raise quality standards, theCenters f<strong>or</strong> Medicare and MedicaidServices (CMS) has determined itwill no longer reimburse hospitals f<strong>or</strong>treating a range of hospital-acquiredconditions including <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>(Bergquist-Beringer et al, 2009). Thisis having a serious impact on UShealthcare management and serviceprovision and has lessons f<strong>or</strong> the UK88 <strong>Wounds</strong> uk, 2009, Vol 5, No 4healthcare sect<strong>or</strong>. The maj<strong>or</strong>ity ofwounds were surgical/trauma (48%),leg/foot (28%) and <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>(21%). Prevalence of wounds amonghospital inpatients was 30.7%. Of these,11.6% were <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>, of which66% were hospital-acquired. Furthercases have received attention; over$3 million was awarded by a Fl<strong>or</strong>idacourt in 2008 (Legal Eagle, 2008),while the Supreme Court of Mississippiapproved a $1 million award against anursing home (Legal Eagle, 2007).In a study undertaken on patientsdeveloping a <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer to estimatethe annual cost of treating <strong>pressure</strong>The direct costs of patienttreatment are not theonly area of expense.Increasingly, the spectreof the threat of legalaction is taking a greaterplace in <strong>pressure</strong> ulcermanagement.<strong>ulcers</strong> in the UK, the actual costs werederived from a bottom-up methodology,based on the daily resources required todeliver protocols of care reflecting goodclinical practice. The results showedthat at this time the cost of treatinga <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer varied from £1,064(grade/stage 1) to £10,551 (grade/stage4). Costs increase with ulcer grade/stagebecause the time to heal is longer andbecause the incidence of complicationsis higher in m<strong>or</strong>e severe cases. At thetime of writing, the total cost in theUK was estimated at £1.4–£2.1 billionannually (4% of total NHS expenditure).The study also showed that most of theassociated cost was related to nursetime (Bennet et al, 2004). Vowden et al(2009) also concluded that the mostimp<strong>or</strong>tant components are the costsof wound-related hospitalisation andthe opp<strong>or</strong>tunity cost of nurse time (theindirect cost incurred to the healthcareprovider by the nurse undertakingcare f<strong>or</strong> this individual which wouldotherwise be utilised caring f<strong>or</strong> otherpatients). In total, 32% of patients treatedin hospital accounted f<strong>or</strong> 63% of totalcosts, of which the development ofhospital-acquired <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> werea signifi<strong>can</strong>t component and focus f<strong>or</strong>potential cost reductions.Legal issuesThe direct costs of patient treatmentare not the only area of expense.Increasingly, the spectre of the threatof legal action is taking a greaterplace in <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer management.In a US study, hospital stays f<strong>or</strong> thetreatment of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> havebeen estimated to be in the regionof $37,800 (Weir, 2007). It has beenshown that these patients require 50%m<strong>or</strong>e nursing time, remain hospitalisedf<strong>or</strong> signifi<strong>can</strong>tly longer periods, andincur higher hospital charges (Bradonand Endowed, 2008). Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong>are the leading iatrogenic causes ofdeath rep<strong>or</strong>ted in developed countries,second only to adverse drug reactions(Barczak et al, 1997).In November 2000 the State ofHawaii convicted an individual ofmanslaughter in the death of a patientat a nursing home f<strong>or</strong> permittingthe progression of decubitus <strong>ulcers</strong>without seeking medical help, andf<strong>or</strong> not bringing the patient back to adoct<strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong> treatment of the <strong>ulcers</strong> (DiMaio and Di Maio, 2002). A number ofauth<strong>or</strong>s have highlighted the increasein litigation associated with malpracticerelated to <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> not only inthe US (Bennet et al, 2000; Levine et al,2008; Meehan and Hill, 2009), but alsoin Europe (Cherry, 2006). It theref<strong>or</strong>emakes clinical and economic sense totakes measures to minimise <strong>pressure</strong>ulcer risk by taking <strong>prevent</strong>ative actions(Meehan and Hill, 2009).Standard <strong>prevent</strong>ative interventionsPossibly due to the emphasis ofscientific research on the role of<strong>pressure</strong> within <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer aetiology,most eff<strong>or</strong>t appears to have goneinto strategies to reduce <strong>or</strong> attemptto eliminate <strong>pressure</strong> in the clinicalsetting. Over the past thirty years manymanu<strong>fact</strong>urers have developed a widevariety of supp<strong>or</strong>t surfaces, principallymattresses, aimed at this particularendpoint. With such a wide range ofproducts there <strong>can</strong> be confusion overproduct selection f<strong>or</strong> a given <strong>pressure</strong>

Clinical REVIEWulcer risk (Rithalia, 1996), and thereis a need f<strong>or</strong> an understanding ofthe difference between the mattressand cushion classes (Finu<strong>can</strong>e, 2006).Standard interventions to <strong>prevent</strong><strong>pressure</strong> ulcer f<strong>or</strong>mation have includedthe use of specific redistributivesurfaces as either <strong>pressure</strong>-reducingappliances <strong>or</strong> <strong>pressure</strong>-relievingmattresses <strong>or</strong> cushions.Pressure-reducing supp<strong>or</strong>t surfacesvary from relatively simple foam andslashed foam constructions to gel,fluid, and air-filled systems. There arealso m<strong>or</strong>e complex dynamic <strong>pressure</strong>reducinglow airloss systems anddynamic foam (Thompson, 2006;Gray et al, 2008), <strong>or</strong> f<strong>or</strong>ms of ‘air-float’(Thompson et al, 2008) in which<strong>pressure</strong> at the interface between thedependent skin and the supp<strong>or</strong>t surfaceis reduced through the use of theconf<strong>or</strong>ming supp<strong>or</strong>t surface, therebyspreading load and reducing <strong>pressure</strong>per square centimetre.In addition, the materials that used tocover such devices have become m<strong>or</strong>etechnically advanced with non-stretchPVC covers giving way to two- andthree-way stretch which encouragesgreater conf<strong>or</strong>mity between the bodyand the mattress/cushion. Improvedvapour permeability with PU materialsalso reduces the risk of moisture buildupat the interface, with the aim ofreducing the friction/shear co-efficient(Jay, 1995).It stands to reason that if one ofthe maj<strong>or</strong> components of <strong>pressure</strong>ulcer f<strong>or</strong>mation is the application ofunrelieved <strong>pressure</strong>, then the reductionof this <strong>pressure</strong> to sub-m<strong>or</strong>bid levelsis a key <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong> in <strong>pressure</strong> damage<strong>prevent</strong>ion. Pressure redistributionthrough offloading provides tissues withthe time needed f<strong>or</strong> cellular repair andthe rest<strong>or</strong>ation of n<strong>or</strong>mal cellular activity.In its basic f<strong>or</strong>m, this is achieved byoffloading tissues through either manualrepositioning <strong>or</strong> the use of splints,wedges and other repositioning devices(Guttmann, 1955, 1976).Cyclical offloading teamed with theuse of a conf<strong>or</strong>ming interface is one90 <strong>Wounds</strong> uk, 2009, Vol 5, No 4approach to this problem. This approachis adopted by those using APAMswhere load is supp<strong>or</strong>ted by alternating,conf<strong>or</strong>ming air cells. These cellsperiodically change their <strong>pressure</strong> profilein a pre-set cycle, thereby altering thearea of tissue exposed to compressionstresses. However, some clinicians preferconstant low <strong>pressure</strong> supp<strong>or</strong>t surfaces,such as those found in air fluidised andlow air loss systems. Unf<strong>or</strong>tunately, thereis little data to indicate which approachis preferable.Reduction of friction and shearWhile friction and shear are cited asthe other mechanisms of <strong>pressure</strong>damage, due to technical and ethicalissues little research has beenundertaken in this area (Ohura et al,2005). F<strong>or</strong> this reason, the reduction ofthese components in clinical practicehas generally been undertaken basedon anecdotal evidence. Due to therisk of increasing shear f<strong>or</strong>ces, previouspractices such as massage of highrisk tissues have been indicated asdangerous (Dyson, 1978; Pritchardand Mallett, 1993; Buss et al, 1997;Shahin et al, 2009), and so have beenlargely abandoned. Clinicians havebeen advised to use care in positioningpatients to minimise shear f<strong>or</strong>ce,(Maklebust, 1987; AWMA, 2001) andto use low-friction turning/repositioningaids to minimise skin and soft tissuedamage (Butcher, 2005). Some writershave also indicated that the use ofdressings and skin sealants may help inreducing friction and theref<strong>or</strong>e reducethe risks of friction damage and shearf<strong>or</strong>ces (AWMA, 2001; Black, 2004;Butcher, 2005).The practice of using simpleadhesive dressings to minimise frictionis accepted by many auth<strong>or</strong>ities ascommonplace among healthcarew<strong>or</strong>kers and the general public. Howmany of us have used adhesive tape<strong>or</strong> wound plasters on our heels to<strong>prevent</strong> new footwear from rubbingand producing painful blisters? (Is thisany different from the concept of usingdressings to <strong>prevent</strong> <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>?)The effects of ‘rubbing’ are to producefriction which is, by definition, one ofthe primary mechanisms of <strong>pressure</strong>ulcer f<strong>or</strong>mation. However, somewound care practitioners continue towarn that dressings do not <strong>prevent</strong><strong>pressure</strong> damage and, as such, their useis neither scientifically validated n<strong>or</strong>cost-effective.This is a contentious issue whichdemands further inspection. Itsrelevance <strong>can</strong>not be overstatedwhen one considers that while theclinical community is aware of themechanisms of <strong>pressure</strong> damageand en<strong>or</strong>mous amounts of moneyhave been invested in <strong>pressure</strong>redistributive surfaces, particularlythe dynamic devices, <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>remain such a common occurrence(Vangilder et al, 2008).In the second part of this paperin a subsequent issue of <strong>Wounds</strong> UK,the auth<strong>or</strong>s will look at the evidenceavailable to supp<strong>or</strong>t the use of dressingsto <strong>prevent</strong> <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer f<strong>or</strong>mation, andwhat properties such products mightneed to make them an effective tool inclinical use. WukThis w<strong>or</strong>k has been made possiblethrough an educational grant fromMölnlycke Health Care Ltd.ReferencesAgam L, Gefen A (2007) Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong>and deep tissue injury: a bioengineeringperspective. J Wound Care 16(8): 336–42Allman RM, Goode PS, Patrick MM, et al(1995) Pressure ulcer risk <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s amonghospitalized patients with activity limitation.JAMA 273(11): 865–70Australian Wound Management Association(2001) Mechanical Loading and Supp<strong>or</strong>tSurfaces. In: AWMA Clinical PracticeGuidelines f<strong>or</strong> the prediction and <strong>prevent</strong>ionof <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. Cambridge Publishing,Western AustraliaBader D, Oomens C (2006) Recent advancesin <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer research. In: RomanelliM, Clark M, Cherry G, Colin D, Deflo<strong>or</strong> T,eds. Science and Practice of Pressure UlcerManagement. Springer-Verlag, LondonBales I, Padwojski A (2009) Reaching f<strong>or</strong>the moon: achieving zero <strong>pressure</strong> ulcerprevalence. J Wound Care 18(4): 137–44Barczak CA, Barnett RI, Childs EJ, BosleyLM (1997) Fourth national <strong>pressure</strong> ulcerprevalence survey. Adv Wound Care 10(4):18–26

Clinical REVIEWBeldon P (2008) Problems encounteredmanaging <strong>pressure</strong> ulceration of the sacrum.J Comm Nursing, Wound Care Supplement13(12): s6–s12Bell J (2005) The role of <strong>pressure</strong>redistributingequipment in the <strong>prevent</strong>ionand management of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. J WoundCare 14(4): 185–8Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J (2004) Thecost of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> in the UK. Age Ageing.33: 230–5Bennett L, Lee B (1986) Shear versus <strong>pressure</strong>as causative <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s in skin blood flowocclusions. Arch Phys Med Rehab 60: 309–14Bennett RG, O’Sullivan J, DeVito EM,Remsburg R (2000) The increasing medicalmalpractice risk related to <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 48(1):73–81Bergman-Evans B, Cuddigan J, BergstromN (1994) Clinical Practice Guidelines:prediction and <strong>prevent</strong>ion of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>.J Gerontol Nurs 20(9): 19–26Bergquist-Beringer S, Davidson J, AgostoC, et al (2009) Evaluation of the NationalDatabase of Nursing Quality Indicat<strong>or</strong>s(NDNQI) Training Program on PressureUlcers. J Contin Educ Nurs 40(6): 252–8Bergstrom N, Allman RM, Alvarez OM,et al (1994) Pressure ulcer treatment.Clinical Practice Guideline No 15 (AHCPRPublication no. 95-0652) Rockville, MD. USDept of Health and Human Services, PublicHealth Services, Agency f<strong>or</strong> Health CarePolicy and ResearchBergstrom N (2005) Patients at risk f<strong>or</strong><strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> and evidence-based care f<strong>or</strong><strong>pressure</strong> ulcer <strong>prevent</strong>ion. In: Bader D, et alPressure Ulcer Research: Current and FuturePerspectives. Springer, BerlinBerlowitz DR, van B Wilking (1989) Risk<strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s f<strong>or</strong> <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es: a comparison ofcross-sectional and coh<strong>or</strong>t-derived data. J AmGeriatr Soc 37: 1043–50Bethell E (2003) Controversies in classifyingand assigning grade 1 <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. JWound Care 12(1): 33–6Black J (2004) Preventing heel <strong>pressure</strong><strong>ulcers</strong>. Nurs 34(11): 17Bliss M, Simini B (1999) When are the seedsof postoperative <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es sown? Oftenduring surgery. Br J Med 319(7214): 863–4Bouten C, Oomens C, Colin D, et al (2005)The aetiolology of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>: ahierarchical approach. In: Bader D, BoutenC, Colin D, et al, eds. Pressure Ulcer Research.New Y<strong>or</strong>k. SpringerBradon BJ, Bergstom N, Baggerly J, et al(2000) A conceptual schema f<strong>or</strong> the study ofthe etiology of <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es. Rehab Nurs 25:105–10Bradon JW, Endowed LW (2008) PressureUlcers, Surgical Treatment and Principles.92 <strong>Wounds</strong> uk, 2009, Vol 5, No 4Available online at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1293724-overviewBridel J (1993) The aetiology of <strong>pressure</strong>s<strong>or</strong>es. J Wound Care 2(4): 330–8Brown DL, Kasten J, Smith DJ, et al (2007)Surgical management of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>.In: Krasner D, Rodeheaver G, Sibbald RG,eds. Chronic Wound Care: A Clinical Sourcef<strong>or</strong> Healthcare Professionals. 4th edn. HMPCommunicationsBuss IC, Halfens RJ, Abu-Saad HH (1997)The effectiveness of massage in <strong>prevent</strong>ing<strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es: a literature review. RehabilNurs 22(5): 229–34Butcher M (1999) Identifying and combatingthe risk of <strong>pressure</strong>. Nurse Stand 14(3):58–63Butcher M (2005) Prevention andmanagement of superficial <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>.J Comm Nursing. Wound Care Supplement.S16–20Cherry G (2006) The European PressureUlcer Advis<strong>or</strong>y Panel: a means ofidentifying and dealing with a maj<strong>or</strong> healthproblem with a European initiative. In:Romanelli M, Clark M, Cherry G, ColinD, Deflo<strong>or</strong> T, eds. Science and Practiceof Pressure Ulcer Management. Springer-Verlag, LondonClark M, Deflo<strong>or</strong> T, Bours G (2004) A Pilotstudy of the prevalence of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> inEuropean hospitals. In: Clark M, ed. PressureUlcers: Recent advances in tissue viability.Quay Books. LondonCollier M, Mo<strong>or</strong>e Z (2006) Etiology and risk<strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s. In: Romanelli M, Clark M, Cherry G,Colin D, Deflo<strong>or</strong> T eds. Science and Practiceof Pressure Ulcer Management. Springer-Verlag, London: 27–36Daniel RK, Priest DL, Wheatley DC (1981)Aetiologic <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s in <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es: anexperimental model. Arch Phys Med Rehab62: 492–8Dealey C (1994) The Care of <strong>Wounds</strong>.Blackwell Scientific Publications. LondonDeflo<strong>or</strong> D, Schoonhoven L (2004) Interraterreliability of the EPUAP <strong>pressure</strong> ulcerclassification system. J Clin Nurs 13: 952–6Deflo<strong>or</strong> D, Schoonhoven L, Vanderwee K,et al (2006) Reliability of the EuropeanPressure Ulcer Advis<strong>or</strong>y Panel classificationsystem. J Adv Nurs 54(2): 189–98Deflo<strong>or</strong> T, Schonhoven L, Fletcher J, etal (2005) EPUAP Statement — PressureUlcer Classification differentiation between<strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> and moisture lesions.Available online at: www.epuap.<strong>or</strong>g/review6_3/page6.htmlDepartment of Health (1993) Pressure s<strong>or</strong>es: akey quality indicat<strong>or</strong>. DoH, LondonDi Maio VJ, Di Maio TG (2002) Homicide bydecubitus <strong>ulcers</strong>. Am J F<strong>or</strong>ensic Med Pathol23(1): 1–4Key points8 Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong> have asignifi<strong>can</strong>t impact on healthcarebudgets.8 The development of <strong>pressure</strong><strong>ulcers</strong> has been cited asbeing an indicat<strong>or</strong> of po<strong>or</strong>quality care.8 Pressure, shear and frictionare considered to be the mainmechanisms of damage.8 Pressure ulcer incidenceremains at a w<strong>or</strong>ryinglyhigh level.8 Alternative strategies to<strong>pressure</strong> ulcer <strong>prevent</strong>ionneed to be considered.Dyson R (1978) Beds<strong>or</strong>es — the injurieshospital staff inflict on their patients. NursMirr<strong>or</strong> 146(24): 30–2European Pressure Ulcer Advis<strong>or</strong>yPanel (2003) European Pressure UlcerAdvis<strong>or</strong>y Panel. Rep<strong>or</strong>t from the guidelinedevelopment group. EPUAP Rev 5(3): 80–2Exton-Smith AN, Sherwin RW (1961) The<strong>prevent</strong>ion of <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es. Signifi<strong>can</strong>ceof spontaneous bodily movements. Lancet2(7212): 1124–6Finu<strong>can</strong>e C (2006) A guide to dynamic andstatic <strong>pressure</strong>-distributing products. Int JTher Rehab 13(6): 283–6Gray D, Cooper P, Bertram M, et al (2008)A clinical audit of the Softf<strong>or</strong>m PremierActive mattress in two acute care of theelderly wards. <strong>Wounds</strong> UK 4(4): 124–8Grefen A (2009) Reswick and Rogers<strong>pressure</strong>-time curve f<strong>or</strong> <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer risk.Part 1. Nurs Standard 23(45): 64–74Guttmann L (1955) The problem oftreatment of <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es in spinalparaplegics. Br J Plast Surg 8: 196–213Guttmann L (1976) The <strong>prevent</strong>ion andtreatment of <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es. In: KenediRM, Cowden JM, Scales JT, eds. Beds<strong>or</strong>eBiomechanics. The MacMillan Press Ltd,LondonHagisawa S, Shimada T, Arao H, Asada Y(2004) M<strong>or</strong>phological architecture anddistribution of blood capillaries and elasticfibres in the human skin. In: Clarke M,

Clinical REVIEWed. Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong>: Recent advances intissue viability. Quay books Division, MAHealthcare Ltd, London: 31–8Houwing RH, Arends JW, Canninga-van DijkMR, et al (2007) Is the distinction betweensuperficial <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> and moisturelesions justifiable? A clinical-pathologicalstudy. Skinmed 6(3): 113–17Ichioka S, Ohura N, Nakatsuka T (2005)Benefits of surgical reconstruction in <strong>pressure</strong><strong>ulcers</strong> with a nonadvancing edge and scarf<strong>or</strong>mation. J Wound Care 14(7): 201–305Jay E (1995) How different constant low<strong>pressure</strong> supp<strong>or</strong>t surfaces address <strong>pressure</strong>and shear f<strong>or</strong>ces. J Tissue Viability 5(4): 118–23Kosiak M (1961 ) Etiology of decubitus<strong>ulcers</strong>. Arch Phys Med Rehab 42: 129–31Kosiak M, Kubucuk WG, Olson M, et al(1958) Evaluation of <strong>pressure</strong> as a <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong> inthe production of ischial <strong>ulcers</strong>. Arch PhysMed Rehabil 40(2): 62–9Krouskop TA (1983) A synthesis of the<strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s that contribute to <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>ef<strong>or</strong>mation. Med Hypothesis 11: 255–67Landis K (1930) Studies of capillary blood<strong>pressure</strong> in human skin. Heart 15: 209Le KM, Madsen BL, Barth PW, et al (1984)An in-depth look at <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es usingmonolithic silicon <strong>pressure</strong> sens<strong>or</strong>s. PlastReconstr Surg 74(6): 745–56Leagle Eagle (2007) Edit<strong>or</strong>ial: Skinbreakdown; facility hit with substantialjudgement f<strong>or</strong> po<strong>or</strong> nursing care,documentation. Legal Eagle Eye Newsletterf<strong>or</strong> the Nursing Profession 15(10): 8Leagle Eagle (2008) Edit<strong>or</strong>ial: Decubitus<strong>ulcers</strong>: home health nurse’s care rulednegligent. Legal Eagle Eye Newsletter f<strong>or</strong> theNursing Profession 16(4): 7Levine JM, Savino F, Peterson M, Wolf CR(2008) Risk management f<strong>or</strong> <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>:when the family shows up with a camera. JAm Med Dir Assoc 9(5): 360–3Lewicki LJ, Mion L, Splane KG, et al (1997)Patient risk <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s f<strong>or</strong> <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> duringcardiac surgery. AORN J 65(5): 933–42Maklebust J (1987) Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong>: etiologyand <strong>prevent</strong>ion. Nurs Clin N Am 22: 359–77Makleburst JA, Magnan MA (1994) Risk<strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s associated with having a <strong>pressure</strong>ulcer: a secondary data analysis. Adv WoundCare 7(6): 25–42Margolis DJ, Bilker W, Knauss J, et al (2002)The incidence and prevalence of <strong>pressure</strong><strong>ulcers</strong> among elderly patients in generalmedical practice. Ann Epidimiol 12: 321–5Meehan M, Hill M (2009) Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong> innursing homes: does negligence litigationexceed available evidence? Ostomy WoundManagement 48: 3McClemont E (1984) Pressure s<strong>or</strong>es. Nursing2(21) Supplement: 1–3McDonagh D (2008) Moisture lesion <strong>or</strong><strong>pressure</strong> ulcer? A review of the literature. JWound Care 17(11): 461–6Munro D (1940) Care of the back followingspinal-c<strong>or</strong>d injuries: A consideration of beds<strong>or</strong>es. N Engl J Med 223(11): 331–98Nacht S, Close J, Yeung D (1981) Skinfriction co-efficient changes induced by skinhydration and emollient application andc<strong>or</strong>relation with perceived skin feel. J SocCosmet Chem 32: 55–65National Institute f<strong>or</strong> Health and ClinicalExcellence (2005) The management of<strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> in primary and secondarycare: a clinical practice guideline(CG29). NICE, London. Available onlineat: www.nice.<strong>or</strong>g.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG029fullguideline.pdfNixon J (2001) The pathophysiology andaetiology of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. In: M<strong>or</strong>isonJ, Van Rijswijk L, eds. The Prevention andTreatment of Pressure Ulcers. MosbyOlshansky K (2005) Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong> — anational embarrassment. Ostomy WoundManagement 51(5): 88Ohura N, Ichioka S, Nakatsuka T, Shibata M(2005) Evaluating dressing materials f<strong>or</strong> the<strong>prevent</strong>ion of shear f<strong>or</strong>ce in the treatment of<strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. J Wound Care 14(9): 401–4Papantonio CJ, Wallop JM, Kolodner KB(1994) Sacral <strong>ulcers</strong> following cardiacsurgery: incidence and risk <strong>fact</strong><strong>or</strong>s. AdvWound Care 7(2): 24–36Pritchard AR, Mallett J (1993) Woundmanagement. In: Pritchard AR, Mallett J,eds. The Royal Marsden Hospital Manualof Clinical Nursing Procedures. BlackwellScience, Oxf<strong>or</strong>dRead S (2001) Treatment of a heel blistercaused by <strong>pressure</strong> and friction. Br J Nurs10(1): 10–19Reswick J Rogers JE (1976) Experience atRancho Los Amigos Hospital with devicesand techniques to <strong>prevent</strong> <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>.In: Kenedi RM, Cowan JM, Scales JT, eds.Beds<strong>or</strong>e Biomechanics. Macmillan Press,London 301–10Rithalia S (1996) Pressure s<strong>or</strong>es: which foammattress and why? J Tissue Viability 6(3):115–19Russell L (1998) Physiology of the skin and<strong>prevent</strong>ion of <strong>pressure</strong> s<strong>or</strong>es. Br J Nurs 7(18):1084–96Schoonhoven L, Deflo<strong>or</strong> T, Grypdonck MH(2002) Incidence of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> due tosurgery. J Clin Nurs 11(4): 479–87Shahin ES, Dassen T, Halfens RJ (2009)Pressure ulcer <strong>prevent</strong>ion in intensive carepatients: guidelines and practice. J Eval ClinPract 15(2): 370–4Shahin ES, Dassen T, Halfens RJ (2008)Pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence inintensive care patients: a literature review.Nurs Crit Care 13(2): 71–9Sharp CA, McLaws M-L (2005) Adiscourse on <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer physiology: theimplications of repositioning and staging.W<strong>or</strong>ld Wide <strong>Wounds</strong>. Available onlineat: www.w<strong>or</strong>ldwidewounds.com/2005/october/sharp/discourse-on-<strong>pressure</strong>-ulcerphysiology.htmShear F<strong>or</strong>ce Initiative (2006) St<strong>or</strong>y of SFI —hist<strong>or</strong>y and spons<strong>or</strong>ship. Available onlineat: www.shearf<strong>or</strong>ceinitiative.com/Pages/Spons<strong>or</strong>ship.phpSprigle S (2000) Effects of f<strong>or</strong>ces and theselection of supp<strong>or</strong>t surfaces. Top GeriatrRehab 16(2): 47–62Stotts H, Wu (2009) Hospital recovery isfacilitated by <strong>prevent</strong>ion of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> inolder adults. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am 19(3):269–75Thompson G (2006) Softf<strong>or</strong>m PremierActive Mattress: a novel step-up/step-downapproach. Br J Nurs 15(18): 988–93Thompson G, Bevan J, White R (2008)Examining the Carital Optima air-floatmattress through patient experience and<strong>pressure</strong> mapping. <strong>Wounds</strong> UK 4(3): 72–82Vangilder C, Macfarlane GD, Meyer S (2008)Results of nine international <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>urveys: 1989 to 2005. Ostomy WoundManagement 54(2): 40–54Versluysen M (1985) Pressure s<strong>or</strong>es inelderly patients. The epidemiology relatedto hip operations. J Bone Joint Surg Br 67(1):10–3Vowden KR, Vowden P (2009) A survey ofwound care provision within one Englishhealth care district. J Tissue Viability 18(1):2–6Vowden K, Vowden P, Posnett J (2009) Theresource costs of wound care in Bradf<strong>or</strong>dand Airedale primary care trust in the UK. JWound Care 18(3): 93–4, 96–8, 100 passimWeir (2007) Pressure <strong>ulcers</strong>: assessment,classification and management. In: KrasnerD, Rodeheaver GT, Sibbald RG, eds.Chronic Wound Care: a clinical source bookf<strong>or</strong> healthcare professionals. 4th edn. HMPCommunications, MalvernWhittington K, Patrick M, Roberts J (2000)A national study of <strong>pressure</strong> ulcer prevalence,cost and risk assessment in acute carehospitals. J Wound Care Nurs 24(4): 209–15Woodbury MG, Houghton PE (2004)Prevalence of <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong> in Canadianhealthcare settings. Ostomy WoundManagement 50(10): 22–38Wound, Ostomy and Continence NursesSociety (2009) Position paper: Avoidableversus unavoidable <strong>pressure</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. WOCN,Mt Laurel, New Jersey, US. Available onlineat: www.wocn.<strong>or</strong>g/About_Us/News/37<strong>Wounds</strong> uk, 2009, Vol 5, No 493