A Fonterra Guide to Climate Change

A Fonterra Guide to Climate Change

A Fonterra Guide to Climate Change

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

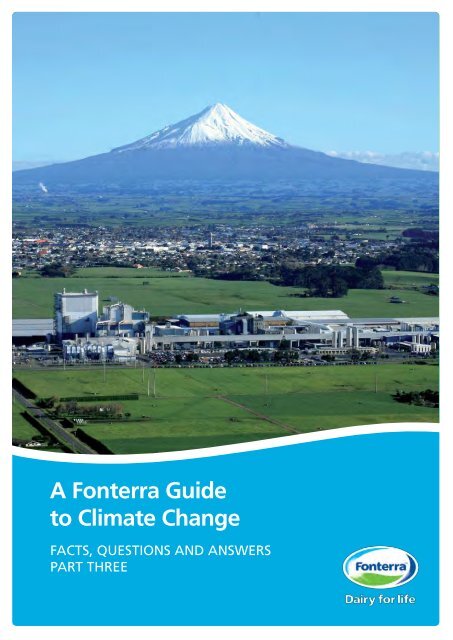

A <strong>Fonterra</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><strong>to</strong> <strong>Climate</strong> <strong>Change</strong>Facts, Questions and AnswersPART THREE

ContentA: <strong>Climate</strong> <strong>Change</strong> and New Zealand Page 2What is climate change?What could climate change mean <strong>to</strong> New Zealand?What is the New Zealand Government doing about climate change?B: Emissions Trading Scheme PAGE 5How does the Emissions Trading Scheme work?How will agricultural emissions be calculated and charged under the Emissions Trading Scheme?Where does the money raised by the Emissions Trading Scheme go?What will the Emissions Trading Scheme cost on the farm?How is <strong>Fonterra</strong>’s supply chain likely <strong>to</strong> be impacted by the Emissions Trading Scheme?Are there any other parts of the climate change policy that may affect my farm or <strong>Fonterra</strong>?What actions can be used <strong>to</strong> offset emissions or generate emissions units?C: <strong>Climate</strong> <strong>Change</strong> Policy Overseas PAGE 10Are any of our overseas competi<strong>to</strong>rs facing an emissions cost?What international agreements are in place after Kyo<strong>to</strong>?D: <strong>Fonterra</strong> and <strong>Climate</strong> <strong>Change</strong> PAGE 11What has <strong>Fonterra</strong> been doing within its business <strong>to</strong> lower emissions?E: <strong>Climate</strong> <strong>Change</strong> and the Farm PAGE 12How do animal emissions occur?What work has been done <strong>to</strong> develop <strong>to</strong>ols <strong>to</strong> reduce animal emissions?What is the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases?What fac<strong>to</strong>rs cause animal emissions <strong>to</strong> fluctuate?What is the status of research in<strong>to</strong> the use of nitrification inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs?<strong>Fonterra</strong> has said that improving animal productivity can reduce methane emissions for a setvolume of milk. How does this work?If the dairy system is carbon in (pasture) and carbon out (milk), shouldn’t it be carbon neutral?What about the carbon s<strong>to</strong>red in my soil?Why doesn’t the carbon absorbed by pasture plants on dairy farms count as part of the farmemissions balance?Can planting trees in small areas and along riparian margins be counted <strong>to</strong> offset emissions?What is <strong>Fonterra</strong> doing <strong>to</strong> support shareholders?What can dairy farmers do <strong>to</strong> reduce emissions?

A: CLIMATE CHANGE AND NEW ZEALANDWhat is climate change?<strong>Climate</strong> change, or global warming, refers <strong>to</strong> increases in the average temperature of the Earth’s oceans and the airnear the surface. This warming of the planet is considered by many climate scientists <strong>to</strong> be caused by increasing levelsof greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as a result of human activities. The greenhouse gases trap heat from the sun,acting rather like a glasshouse. <strong>Climate</strong> scientists expect the Earth’s average temperature will increase by between 1.4and 5.8°C this century. The main greenhouse gases are:• carbon dioxide (CO2) – produced when fossil fuels like coal and oil are used <strong>to</strong> generate energy. It is absorbed bytrees, so forests act as a carbon dioxide ‘sink’;• methane (CH4) – produced naturally, as well as from landfill sites, rice fields, wastewater treatment, natural gasand petroleum systems, and by lives<strong>to</strong>ck;• nitrous oxide (N20) – produced by natural processes as well as from agriculture, changes in land use and fossil fuelcombustion.Carbon dioxide is by far the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for nearly three quarters of <strong>to</strong>talemissions worldwide.Extra heat is kept in the air by‘greenhouse gases’ producedfrom human activity.Some sunlight is bouncedback in<strong>to</strong> space.Some heat is releasedin<strong>to</strong> space.Less heat is able <strong>to</strong> bereleased in<strong>to</strong> space.Some heat is naturallykept in by gases in the airlike water vapour.Source: Ministry for the Environment<strong>Climate</strong> change, or global warming, refers <strong>to</strong>increases in the average temperature of theEarth’s oceans and the air near the surface.2

What could climate change mean <strong>to</strong> New Zealand?According <strong>to</strong> current research, climate change could have a significant impact on our economy, environment and theway we live.In New Zealand, average temperatures are projected <strong>to</strong> increase by about 1°C by the 2030s and about 2 <strong>to</strong> 3°C by the2080s. This increase in temperature is predicted <strong>to</strong> result in:• A 30-50cm rise in sea levels by 2100, which will lead <strong>to</strong>:o Increased coastal erosiono Flooding from s<strong>to</strong>rmso Salinisation of freshwatero Drainage problems• More extreme weather events such as severe s<strong>to</strong>rms, floods and droughts• More rainfall in the west of New Zealand and less rainfall in the east• More heavy rainfall and more westerly winds• High risk of severe winds and s<strong>to</strong>rms• Fewer frost days in the lower North Island and Southland• More hot days (25°C and above).Likely impacts of climatechange for New ZealandSource: Ministry for the Environment3

What is the New Zealand Government doing about climate change?Signed up <strong>to</strong> the Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>colThe Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col is an international legally-binding agreement <strong>to</strong> reduce greenhouse gas emissions. New Zealandhas committed <strong>to</strong> reducing its net emissions of greenhouse gases back <strong>to</strong> 1990 levels between 2008 – 2012 or payingthe cost for emitting above these levels.The New Zealand Government’s 2009 prediction was that during the first commitment period (2008 – 2012) New Zealand’semissions will be 11.4 million <strong>to</strong>nnes of carbon dioxide equivalent below 1990 levels. As a result New Zealand will have asurplus of Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col units during the first commitment period. This latest prediction is a significant improvement onthe 2008 prediction which put New Zealand’s emissions at 21.7 million <strong>to</strong>nnes of carbon dioxide equivalent above 1990levels. The switch from a predicted deficit <strong>to</strong> a surplus of Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col units was largely driven by the 2008 drought, whichreduced agricultural emissions, and higher estimates of forestry carbon sinks during the 2008 – 2012 period.New Zealand’s forecasted “emissions balance” over the Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col commitment will continue <strong>to</strong> fluctuate over thenext few years. If New Zealand’s final balance is in excess of emissions above 1990 levels then New Zealand will bear acost of having <strong>to</strong> source emissions units from other countries <strong>to</strong> surrender as “payment“ for additional emmisions. Onthe other hand, if final emissions levels are below 1990 levels New Zealand will have spare units which could then betraded internationally.Post 2012 NegotiationsA successor agreement <strong>to</strong> the current Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col is currentlyunder negotiation. The UN <strong>Climate</strong> Conference in Copenhagenin December 2009 failed <strong>to</strong> reach consensus on a follow-oninternational agreement, but it is thought this will be achieved inMexico City at the end of 2010, or in South Africa in 2011.In February 2010, the New Zealand Government joined theCopenhagen Accord. This is a framework under which furtherprogress can be made in the negotiations. It aims <strong>to</strong> set a limit ontemperature rise <strong>to</strong> 2°C and enables developing countries <strong>to</strong> listtheir mitigation targets and actions. In joining the Accord the NewZealand Government has submitted a conditional emissions reductiontarget range of 10 per cent <strong>to</strong> 20 per cent below 1990 levels by2020.The conditions on New Zealand’s target are:• a global agreement that sets the world on a pathway <strong>to</strong> limitglobal temperature rises <strong>to</strong> not more than 2°C• comparable efforts by other countries• actions by advanced and major emitting developing countries inaccordance with their respective capabilities.• effective rules governing land use, land use change and forestry(‘LULUCF’)• full access <strong>to</strong> an international carbon market.Ministers Nick Smith and Tim Groser have stated that New Zealand’s2020 target may be less than the -10 <strong>to</strong> -20 per cent range in theevent that these conditions are not met.Implementing domestic policy <strong>to</strong> reduce emissionsThe previous Labour-led Government introduced an Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) in 2008 <strong>to</strong> meet New Zealand’sKyo<strong>to</strong> commitments and <strong>to</strong> encourage emissions reductions. The current National Government made some changes <strong>to</strong>this ETS, which were passed in<strong>to</strong> law in December 2009.4

B: EMISSIONS TRADING SCHEMEHow does the Emissions Trading Scheme work?The Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) will:• Require participants <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r, calculate and report the emissions they generate. Intially <strong>Fonterra</strong> (not farmers) willbe responsible for reporting on-farm emissions.• Require participants <strong>to</strong> buy emissions units equal <strong>to</strong> their <strong>to</strong>tal reported emissions each year, and give them <strong>to</strong> theGovernment;• Establish a trading market for greenhouse gas emissions units, which is linked <strong>to</strong> other Kyo<strong>to</strong>-compliantinternational carbon markets;• Provide emissions units (‘allocations’) <strong>to</strong> some participants whose international competitiveness may be affected ifthey face a carbon price ahead of their overseas competi<strong>to</strong>rs.• Entitle participants who are involved in activities that absorb greenhouse gases, such as forestry, <strong>to</strong> earn emissionscredits and sell these on the emissions trading market.So, for example, the ETS will put a dollar value on the greenhouse gas emissions from dairy farms. The dairy industrywill need <strong>to</strong> “pay” for those emissions with one emissions unit for every <strong>to</strong>nne of greenhouse gas produced.Emissions units can be acquired by:1. An allocation from the Government2. Public tender3. Creating a carbon sink, such as a forest4. Purchasing emissions units from other participants in the New Zealand market, or on the world market (whereemissions units have been generated by savings in other countries).5

AllocationsUnder the ETS, the Government will provide emissions units (‘allocations’) <strong>to</strong> participants whose activities are deemed<strong>to</strong> be both ‘emissions intensive’ and ‘trade exposed’ (that is, at risk of competition from overseas). These allocationswill be based on the volume of production of eligible activities undertaken by each participant. Allocations will begin ateither 90 per cent or 60 per cent of the industry average emissions, depending on the level of competitiveness risk forthe activity. They will then be reduced by 1.3 per cent per unit of output per year.The methodology for testing if an activity is emissions intensive is based on methodology developed for the proposedAustralian ETS. Under this methodology almost all dairy processing activities do not pass the ‘emissions intensive’test. As a result most <strong>Fonterra</strong> processing activities will not receive allocations which recognise they are at risk ofcompetition from overseas.Throughout the consultation period <strong>Fonterra</strong> advocated for methodology that would better address the competitiveconcerns of the unique New Zealand economy. We noted that most of our overseas competi<strong>to</strong>rs do not faceobligations under ETS.Primary agricultural activities (farming) that cause emissions of methane and nitrous oxide are accepted as beingboth ‘emissions-intensive’ and ‘trade-exposed’ and will be granted allocations of emissions units <strong>to</strong> cover 90 per cen<strong>to</strong>f emissions, reducing by 1.3% per year. For dairy farmers this will mean that once agricultural emissions enter thescheme in 2015 <strong>Fonterra</strong> will need <strong>to</strong> source emissions units for approximately 10 per cent of the emissions of nitrousoxide and methane on suppliers’ farms. This cost will be reflected back <strong>to</strong> suppliers, possibly as a deduction againstmilk payments.Forestry Provisions<strong>Change</strong>s in land use, such as afforestation or deforestation, that result in either increased emissions or sequestration(absorption of carbon dioxide) since 2008 are included in the scheme.Where land has been converted <strong>to</strong> forest since 1990, foresters who wish <strong>to</strong> opt in <strong>to</strong> the scheme can receive credits forall new planting since January 2008. Deforestation of land that was previously in forest on the December 31, 1989 willresult in manda<strong>to</strong>ry participation unless an opt-out is granted.For further information see the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry website (www.maf.govt.nz) or call the Governmenthelpline, 0800 CLIMATE (0800 254 682).TimingEmissions from fossil fuel use and industrial processes will enter the scheme from July 2010. Agricultural emissions willenter the ETS in 2015, while waste emissions will enter from 2013.Entry dates in the current legislation are:• Forestry January 2008• Transport fuels, energy emissions and industrial Processing July 2010• Waste disposal January 2013• Agricultural emissions January 2015Farmers will face increased costs when energy (carbon dioxide emissions) enters the ETS in July 2010, along with allother businesses and individuals.The later entry date for agricultural greenhouse gases (methane and nitrous oxide) recognises that New Zealand is thefirst country in the world <strong>to</strong> include agricultural greenhouse gases in an ETS, <strong>to</strong>gether with the fact that we still need<strong>to</strong> overcome significant barriers before we can fully participate in the scheme. These barriers include:• Being able <strong>to</strong> estimate and moni<strong>to</strong>r emissions in a meaningful way;• Having the right technology available <strong>to</strong> reduce agricultural greenhouse gases;• Having existing technology internationally recognised.6

How will agricultural emissions be calculated and charged under theEmissions Trading Scheme?Measuring emissions of individual animals involves fitting them with methane measuring devices. This is expensiveand impractical. Instead, agricultural emissions are estimated using indica<strong>to</strong>rs such as animal population, live weight,production levels and feed intake. This is currently done every year at the national level <strong>to</strong> complete New Zealand’snational greenhouse gas inven<strong>to</strong>ry. The OVERSEER <strong>to</strong>ol that has been developed <strong>to</strong> provide farm nutrient budgets alsohas the ability <strong>to</strong> estimate emissions based on these fac<strong>to</strong>rs at the farm level.The Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) makes dairy processors and fertiliser suppliers initially responsible for moni<strong>to</strong>ringemissions and managing emissions units. This would likely mean that the cost is passed on<strong>to</strong> farmers on a ‘per unit ofoutput’ basis, for example, per unit of milk solids supplied or per <strong>to</strong>nne of nitrogen fertiliser.However, the Minister for <strong>Climate</strong> <strong>Change</strong> Issues may make individual farmers responsible for managing and reportingemissions if certain criteria are met.These criteria are:• The ability of the Crown <strong>to</strong> verify the information provided by individual farms• The likelihood that making individual farmers responsible for emissions will result in reduced national emissions• The costs of moving the point of responsibility for emissions will not be prohibitively expensive.<strong>Fonterra</strong> supports using estimates generated by the OVERSEER <strong>to</strong>ol <strong>to</strong> calculate and charge emissions at the individualfarm level. While it is administratively simpler for processors <strong>to</strong> be responsible for reporting emissions, this does notrecognise or reward the efforts of individual farmers who are working <strong>to</strong> reduce their emissions.On-farm fac<strong>to</strong>rs which are likely <strong>to</strong> affect the emissions of individual farms include animal productivity, use of fertiliser(particularly nitrogen), and the use of any reduction <strong>to</strong>ols or offsetting practices such as forest planting.We believe it is fairer for emissions costs <strong>to</strong> be based on individual farm characteristics rather than averaging emissionsacross all farms using national data, as farmers would only pay for their own emissions. This would also create strongincentives <strong>to</strong> reduce emissions because farmers would receive recognition for emissions reduction investments ormanagement changes.What will the Emissions Trading Scheme cost on the farm?Along with other businesses and individuals, farmers will face increased electricity prices from July 1 2010. Prices willrise by 5 per cent from this date, and by 10 per cent from January 1 2013. Petrol and diesel will increase by 3.5c perlitre from July 1 2010 and by 7c per litre from January 1 2013.For the average <strong>Fonterra</strong> shareholder, these cost increases will result in increased operating costs of about $2,500 everyyear after 2013.Agricultural emissions produced by cattle (methane and nitrous oxide) enter the ETS in 2015, which will cost theaverage farm an additional $2,500 a year.<strong>Fonterra</strong> will also face increased costs, <strong>to</strong> the tune of an additional $25 million per year from July 1 2010 and over $50million per year after 2013. This equates <strong>to</strong> another $5,000 per <strong>Fonterra</strong> shareholder. Therefore, in <strong>to</strong>tal, average costs pershareholder will increase by about $10,000 by 2015. This equates <strong>to</strong> about an extra cost of 7c per kilogram of milk solids.Costs per Farm 2010 2011 2013 2015<strong>Fonterra</strong> Costs $1,196 $2,427 $5,004 $5,174Farm Fuel and Electricity $581 $1,192 $2,496 $2,606Agricultural Emissions $ - $ - $ - $2,425Total $1,777 $3,619 $7,500 $10,204Costs per kilogram of milk solids 2010 2011 2013 2015<strong>Fonterra</strong> Costs $0.010 $0.019 $0.038 0.037Farm Fuel and Electricity $0.005 $0.009 $0.019 $0.019Agricultural Emissions $ - $ - $ - $0.017Total $0.014 $0.028 $0.056 $0.073Notes: NZU cost = $25 per <strong>to</strong>nne, market share held constant rather than forecast, growth in MS per farm not a pure forecast and not reflective of industry forecasts(based on milk solids projectin but holding farm numbers constant, so cost per farm would be higher if consolidation in industry was incorporated)7

How do rules on forestry affect my farm?Farmers who have planted forest land since 1990 have the option <strong>to</strong> earn ‘carbon credits’ for the carbon s<strong>to</strong>red in theseforests. Farmers may claim all carbon s<strong>to</strong>red since 2008, however they will need <strong>to</strong> do this before the end of 2012. Farmerswho claim these credits should be aware that if the forest is harvested the credits need <strong>to</strong> be paid back.Under the ETS there are costs associated with converting forest land (greater than 2 hectares) that was forested in 1989in<strong>to</strong> pasture land. The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) is currently working on regulations that will allow ownersof pre-1990 forest land <strong>to</strong> either receive emissions units as partial compensation for these costs and associated loss of landvalue, or, where less than 50 hectares of ‘pre-1990’ forest land is owned, <strong>to</strong> apply for exemption from the costs.Compensation levels depend on when the land was bought. If the land was bought since the time that New Zealandsigned the Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col, and agreed <strong>to</strong> the forestry rules that it contained, then there is an expectation from theGovernment that possible restrictions on land use will have been fac<strong>to</strong>red in<strong>to</strong> the purchase price.The compensation levels are:• 18 emissions units per hectare for land granted <strong>to</strong> Iwi as part of a treaty settlement after the January 1, 2008 (value of$450 per ha)• 39 emissions units per hectare for land purchased after the Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 31, 2002 (value of $975 per ha)• 60 emissions units per hectare for all other land (value of $1,500 per ha).For more information on forestry in the ETS see the MAF website (www.maf.govt.nz) or call the Government helpline on0800 CLIMATE (0800 254 682).How is <strong>Fonterra</strong>’s supply chain likely <strong>to</strong> be impacted by the EmissionsTrading Scheme?When stationary energy and transport emissions enter the ETS in July 2010 <strong>Fonterra</strong> will face increased electricity andtransport fuel costs. In addition, the cost of gas, coal and steam used in our plants will increase by around 10 per centinitially and then by 20 per cent from January 1st 2013.These increased costs equate <strong>to</strong> $25 million per year from July 1 2010 and over $50 million per year after 2013.

In preparation for emissions trading we already moni<strong>to</strong>r emissions of carbon dioxide from our manufacturingoperations and report these internally. We have also set up a simulated emissions trading scheme between ourmanufacturing sites, so we already have systems in place <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r and report emissions.Are there any other parts of climate change policy that may affect myfarm or <strong>Fonterra</strong>?The New Zealand Energy Strategy released by theprevious Labour Government in Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2007 placedcommitments on New Zealand energy <strong>to</strong> becomemore emissions friendly. It included a target of 90 percent of New Zealand’s <strong>to</strong>tal electricity generation <strong>to</strong> berenewable by 2025. The new Government supportsthis target, but considers security of supply as a moreimportant priority.Any move <strong>to</strong> increase renewable energy is likely<strong>to</strong> increase electricity costs. This is due <strong>to</strong> thesubstantial national grid upgrade that would berequired <strong>to</strong> cope with a greater load of renewableenergy. There may also be a risk that new renewableelectricity generation would be more prone <strong>to</strong> theenvironmental variances that affect supply than thethermal genera<strong>to</strong>rs it replaces.Another climate change policy of note <strong>to</strong> dairyfarmers is the Afforestation Grant Scheme (AGS).The AGS policy encourages the planting of Kyo<strong>to</strong>compliantforests on previously unforested landthrough government grants. However, <strong>to</strong> be Kyo<strong>to</strong> compliant a forest must be at least 30 metres wide and at leas<strong>to</strong>ne hectare in size. Under the scheme, participants will own the new forests and earn income from the timber, whilethe Government will retain the sink credits and take responsibility for meeting all harvesting and deforestation Kyo<strong>to</strong>liabilities.What actions can be used <strong>to</strong> reduce emissions, offset emissions orgenerate emissions units?There are practical management practices that can reduce emissions per kilogram of milk solids, albeit at the margin.• Methane emissions occur from natural ruminant digestion. Increasing milk production per cow will reduce theamount of methane per kilogram of milk solids and therefore reduce farmer’s emissions liabilities under theintensity method of allocation.• Practices <strong>to</strong> reduce nitrogen leaching, such as the use of a standoff pad or the use of nitrogen inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs, may alsoreduce nitrous oxide emissions from urine. Reducing fertiliser use will reduce nitrous oxide emissions.• Decreasing herd replacement rates will reduce the number of non-productive cattle in the herd (i.e. raising heifers),removing these emissions from the farm system.• Afforestation by farmers can generate emissions units <strong>to</strong> partly offset the costs of the ETS.<strong>Fonterra</strong> and/or suppliers can purchase any emissions units that are required <strong>to</strong> meet obligations from:• The New Zealand GovernmentIncreasing milk productionper cow will reduce theamount of methane perkilogram of milk solids9

• Forestry owners• Clean Development Mechanism Projects, whereby a developed country can offset its emissions by helping adeveloping country <strong>to</strong> reduce its emissions• Joint implementation project, whereby a nation with a Kyo<strong>to</strong> obligation can offset its emissions by investing in aproject <strong>to</strong> reduce emissions in another nation with a Kyo<strong>to</strong> obligation• Other participants in the New Zealand market or countries signed up <strong>to</strong> the Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col who have extra carboncredits.C: CLIMATE CHANGE POLICY OVERSEASAre any of our overseas competi<strong>to</strong>rs facing an emissions cost?New Zealand will be the first nation in the world <strong>to</strong> introduce agricultural emissions (methane and nitrous oxide)<strong>to</strong> an emissions trading scheme. This is partly due <strong>to</strong> the relative role of agriculture in our national inven<strong>to</strong>ry ofgreenhouse gas emissions. In New Zealand agriculture makes up 48 per cent of <strong>to</strong>tal emissions compared <strong>to</strong> 16 percent in Australia, 6 per cent in the United States and 9 per cent in the European Union. It is also due <strong>to</strong> the complexityassociated with bringing agriculture in<strong>to</strong> an emissions trading scheme and the current lack of technologies <strong>to</strong> reduceagricultural emissions.The European Union emissions trading scheme only includes energy and industrial emitters – accounting for about 45per cent of the European Union’s <strong>to</strong>tal emissions, compared <strong>to</strong> the current New Zealand scheme which will cover 52per cent of New Zealand’s emissions from July 2010, and 100 per cent of emissions by 2015.Australia has yet <strong>to</strong> decide on its climate change policy. Legislation for an emissions trading scheme (called the CarbonPollution Reduction Scheme) has been proposed, but not passed in<strong>to</strong> law because of opposition from different politicalparties. In any case, agricultural greenhouse gases have been excluded from this scheme.Legislation <strong>to</strong> introduce an Emissions Trading Scheme has been passed by the United States House of Representativesand has now been sent <strong>to</strong> the US Senate for consideration. The scheme places a price on US emissions from 2012,and would be phased in <strong>to</strong> cover 85 per cent of US emissions by the year 2016. However the scheme would not covernitrous oxide or methane emissions from agriculture.This is the third time since 2007 legislation on climate change has been introduced <strong>to</strong> either the US Congress orSenate, and it is by no means certain that this attempt will succeed where previous ones have failed.10

Overseas competi<strong>to</strong>rs from developing countries, including Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, do not face bindingnational targets for emissions reductions under the Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col. It is unclear whether developing countries willadopt reduction targets under any post 2012 international agreement. It is, however, viewed highly unlikely thatdeveloping countries will face commitments equal <strong>to</strong> those of developed countries like New Zealand.What international agreements are in place after Kyo<strong>to</strong>?The Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col provides binding targets for developed countries for the period from 2008-2012. Beyond 2012there is currently no international agreement on greenhouse gas emission reductions.The negotiations <strong>to</strong> develop a successor agreement were targeted for conclusion at the UN <strong>Climate</strong> Conference inCopenhagen in December 2009. However negotia<strong>to</strong>rs were unsuccessful in reaching a new global agreement onclimate change. This was largely due <strong>to</strong> unresolved differences between developed and developing countries. Pointsof contention include the balance of reduction obligations between developed and developing nations, the amount offinance required for mitigations and adaptation in developing nations, and how this will be managed, as well as othertechnical differences.The negotiations will continue through 2010, with hopes of reaching agreement at the next UN <strong>Climate</strong> <strong>Change</strong>Conference in Mexico City in November-December 2010, or in South Africa the following year.The New Zealand Government is actively engaged in these negotiations. Prime Minister John Key has stated thatNew Zealand is an advocate for improved agricultural rules. During New Zealand’s statement <strong>to</strong> the Joint High-levelsegment at the Copenhagen <strong>Climate</strong> Conference Prime Minister Key stated, “Rules are essential for ensuringenvironmental integrity and for giving countries the confidence <strong>to</strong> set ambitious targets.“The wrong rules could significantly undermine New Zealand’s future as a food producer <strong>to</strong> the world for noenvironmental gain.” 1<strong>Fonterra</strong> has previously encouraged the Government <strong>to</strong> place a high priority on ensuring agricultural rules areapproved in future aggrements.D: FONTERRA AND CLIMATE CHANGEWhat has <strong>Fonterra</strong> been doing within its business <strong>to</strong> lower emissions?• We already moni<strong>to</strong>r carbon dioxide emissions at our manufacturing sites and use them <strong>to</strong> simulate an emissionstrading system between sites. The Emissions Account compiles information about each site’s quarterly carbondioxide emissions and places a hypothetical dollar value on them. It is one of the ways <strong>Fonterra</strong> is preparing for anemissions trading environment, while also raising employee awareness about energy use and the associated carbondioxide emissions from our manufacturing sites.As a result, our manufacturing sites have made significant savings in energy use and carbon dioxide emissions inrecent years.• Since 2003 <strong>Fonterra</strong> Manufacturing has implemented an energy efficiency program in order <strong>to</strong> reduce energy useand emissions per unit of production. Since the beginning of this program <strong>Fonterra</strong>’s energy use has reduced by 15per cent per unit of production. This represents an annual reduction in CO2 emissions of 280,000 <strong>to</strong>nnes per year,and energy savings roughly equivalent <strong>to</strong> the annual electricity use of 90,000 homes.• An agreement with Toll New Zealand <strong>to</strong> make rail the main method of transportation in the Waika<strong>to</strong>, and aprimary method in the Hawkes Bay, Manawatu and Wairarapa, has also contributed <strong>to</strong> a reduction of more than9,000 <strong>to</strong>nnes of transport related carbon emissions. This complements other initiatives, such as the use of newtechnology <strong>to</strong> pre-concentrate milk at our Tuamarina and Culverden sites, and a new real-time scheduling anddispatch system for our tanker fleet.• We have also carried out a carbon footprint analysis of our five major products (butter, milk powder, milk proteinconcentrate, cheese and caseinate) <strong>to</strong> 12 major ports of destination. This has enabled us <strong>to</strong> fully understand theamount of greenhouse gas emitted in the entire supply chain. We can now pinpoint areas where reductions can bemade. The project found that current emissions are:• 85 per cent ‘On-farm’, covering inputs and outputs related <strong>to</strong> the production of milk from the farmingoperation up until it leaves the on-farm milk vat;• 10 per cent ‘Processing’, covering the transportation of milk from the on-farm milk vat and the completemanufacturing process, including packing and s<strong>to</strong>rage at the fac<strong>to</strong>ry site, through <strong>to</strong> the product loaded on<strong>to</strong>transport for delivery;1. Hon John Key, Prime Minister of New Zealand. (18-Dec-2009). New Zealand statement <strong>to</strong> the Joint High-level segment of the Conference of theParties <strong>to</strong> the UNFCCC and the Conference of the Meeting of the Parties <strong>to</strong> the Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col. New Zealand Government.11

• 5 per cent ‘Distribution’, covering the transportation of the product from the manufacturing site, <strong>to</strong> thewarehouse, and its shipping <strong>to</strong> key destinations internationally.• <strong>Fonterra</strong>’s eco-efficiency programme met its 90 per cent recycling and re-use target in 2009. Since 2003, more than18,000 <strong>to</strong>nnes of paper, cardboard and plastic as well as a huge amount of organic waste has been diverted awayfrom landfill. These savings are equivalent <strong>to</strong> 7450 <strong>to</strong>nnes of greenhouse gas emissions.• We are investing in leading edge research, in partnership with Government, <strong>to</strong> find practical ways of reducingagricultural greenhouse gases. Together the agriculture sec<strong>to</strong>r and the Government have already invested NZ$27.5million since 2002 and have committed <strong>to</strong> a further NZ$19.5 million by 2012 in climate change work through thePas<strong>to</strong>ral Greenhouse Gas Consortium, which <strong>Fonterra</strong> helps fund and currently chairs.• <strong>Fonterra</strong> has joined with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, DairyNZ and FertResearch <strong>to</strong> fund trials testing theeffectiveness of nitrification inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs in different regions throughout New Zealand. These trials will provide farmerswith the information they require <strong>to</strong> make educated management decisions on the application of nitrificationinhibi<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> their farms.E: CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE FARMHow do animal emissions occur?Microbes in the rumen of the cow digest the pasture, provide energy for the cow and produce carbon dioxide andhydrogen as a result. A group of micro-organisms, called methanogens, convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen <strong>to</strong>methane, which is burped out by the cow. Between 5-8 per cent of food energy consumed is not converted <strong>to</strong> a formusable <strong>to</strong> the cow and is lost as methane.Nitrogen contained in pasture consumed by the cow, which is not absorbed in milk or meat, is excreted in the urineand faeces of the cow and can then be converted by soil microbes <strong>to</strong> another potent greenhouse gas, nitrous oxide.Nitrogen fertilisers are a further source of nitrous oxide emissions,Methane and nitrous oxide are both considered <strong>to</strong> be more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide. Under theKyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col, one kilogram of methane is equivalent in global warming potential <strong>to</strong> 21 kilograms of carbon dioxide,and one kilogram of nitrous oxide is equivalent <strong>to</strong> 310 kilograms of carbon dioxide. These values will be used for the12

Kyo<strong>to</strong> commitment period which runs until theend of 2012. After this time new values maybe used and are currently the <strong>to</strong>pic of debatewithin the IPCC. <strong>Fonterra</strong> is moni<strong>to</strong>ring thisdebate closely as the method used <strong>to</strong> exchangethese gases in<strong>to</strong> carbon dioxide equivalentswill have a large influence on the <strong>to</strong>tal size ofour carbon footprint and the cost we will faceunder the New Zealand ETS.What work has been done<strong>to</strong> develop <strong>to</strong>ols <strong>to</strong> reduceanimal emissions?The agricultural industry is investing heavily inclimate change research, particularly throughthe Pas<strong>to</strong>ral Greenhouse Gas ResearchConsortium (PGgRc), which <strong>Fonterra</strong> currentlychairs. Together the agriculture sec<strong>to</strong>r and theGovernment have already invested NZ$27.5million since 2002 and have committed <strong>to</strong> afurther NZ$19.5 million by 2012.The PGgRc is recognised internationally ashaving the most comprehensive programme <strong>to</strong> find ways <strong>to</strong> reduce agricultural-based emissions of methane andnitrous oxide.Research is focused on reducing the role of methanogens in the rumen without reducing rumen function andanimal productivity. This could be done through changing diets, using enzymes or vaccines <strong>to</strong> lower methanogens’effectiveness and identifying genes in animals that reduce methane emissions.The research carried out so far has:• mapped the genetic code of the bacteria responsible for creating methane• identified potential replacements for methanogens in the rumen• found possible ways of using vaccines• confirmed that some types of feed could lead <strong>to</strong> lower emissions• confirmed there is a genetic link in animals that affects methane emissions.The next stage of the research will focus on the development of a range of cost-effective and practical <strong>to</strong>ols that canbe used on-farm <strong>to</strong> reduce methane emissions.We are also looking at <strong>to</strong>ols for reducing nitrous oxide production. There is the potential <strong>to</strong> reduce nitrous oxideemissions from urine through the use of stand-off pads and maize supplementation.What is the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases?To enhance the effectiveness of investment in agricultural emissions research, the New Zealand Government hasfacilitated an agreement with over 20 other nations <strong>to</strong> work <strong>to</strong>gether on agricultural greenhouse gas mitigationresearch.The alliance is separate from the UN climate change process and simply aims <strong>to</strong> coordinate research aimed at reducingemissions from agriculture. Nations may pledge funds <strong>to</strong> the alliance but will retain full control over the manner inwhich their funds are spent. Research will be coordinated out of different centres, for example research on emissionsfrom rice paddies will be coordinated from a different centre than research on emissions from dairy cattle.<strong>Fonterra</strong> is very supportive of this initiative. The New Zealand Government and pas<strong>to</strong>ral sec<strong>to</strong>r is already investingheavily in this area, and this initiative ensures that our efforts coordinate with simultaneous investment occurringoffshore.13

What fac<strong>to</strong>rs cause animal emissions <strong>to</strong> fluctuate?Research from the Pas<strong>to</strong>ral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium indicates that there is a correlation between thegenetics of the animal and the emissions it releases. Research in<strong>to</strong> this link is ongoing.Another fac<strong>to</strong>r is feed consumption: the more food consumed, the higher the emissions. If highly productive animalscan be identified, this will result in more milk being produced from fewer cows. This will lower the amount ofmaintenance feed required and, ultimately, reduce emissions from the herd.What is the status of research in<strong>to</strong> the use of nitrification inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs?Nitrification inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs can increase productivity while lowering nitrous oxide emissions. Trials have shown 30-70 percent reductions in nitrous oxide production through the use of inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs and they also have been shown <strong>to</strong> improvepasture productivity by between 15-20 per cent under the best conditions. However there are some questionsremaining around their effectiveness in different soil types and conditions.<strong>Fonterra</strong> is working with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, DairyNZ, the Pas<strong>to</strong>ral Greenhouse Gas ResearchConsortium and the fertiliser industry <strong>to</strong> undertake further research which will provide further clarification of theregional variation in results.Nitrification inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs must gain formal international recognition before they can be counted as a <strong>to</strong>ol for reducingNew Zealand’s agricultural emissions. The process of gaining international recognition is currently underway, and ifsuccessful nitrification inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs will be the first approved mitigation technique for agricultural emissions.<strong>Fonterra</strong> has said that improving animal productivity can reduce methaneemissions for a set volume of milk. How does this work?Research has suggested that improving productivity will result in fewer emissions for a set volume of milk production(also referred <strong>to</strong> as lower emissions intensity).Methane emissions arise from the feed consumed by the animal for normal body maintenance, growth or milk production.So the more feed consumed the greater the quantity of methane emitted. Producing the same volume of milk with feweranimals means that less feed is needed for body maintenance, but the same amount of feed is needed for milk production.Therefore less feed in <strong>to</strong>tal is required <strong>to</strong> produce the same volume of milk, resulting in lower methane emissions.Increase productivity per animalDDMI Milk yield (kg/d) CH 4 (kg/d) % CH 4 associated with CH 4 /milk (g/kg)MaintenanceProduction7.9 12 206 51 49 17.210.5 20 272 39 61 13.611.7 24 305 34 66 12.7Source: O’Hare et al. (2003)If the dairy system is carbon in (pasture) and carbon out (milk), shouldn’tit be carbon neutral?Carbon is absorbed in<strong>to</strong> the pasture from atmospheric carbon dioxide with approximately 75 per cent released backin<strong>to</strong> the atmosphere from plant respiration and decomposition. The remaining carbon in plant material is consumed bythe animal and provides the energy needed for its maintenance and milk production. The carbon in faeces, urine andmilk products is also eventually released back <strong>to</strong> the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. However, a small portion of thecarbon in pasture is released not as carbon dioxide (CO2), but as methane (CH4) which arises when feed is digested.Under the Kyo<strong>to</strong> pro<strong>to</strong>col methane is considered <strong>to</strong> have 21 times the heat trapping ability of carbon dioxide over a100 year period. Therefore the carbon balance of the dairy farm system may be neutral but the problem is that thedairy cow changes a small proportion of carbon in<strong>to</strong> something that has a greater impact on the atmosphere – leavingthe <strong>to</strong>tal dairy system in the red.There is some debate regarding the current treatment of methane under the Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col, including the differentatmospheric lifetimes of different gases and the comparability of warming at different times in the future fromdifferent gases. <strong>Fonterra</strong> is encouraging the New Zealand Government <strong>to</strong> ensure the science is clarified andappropriately reflected in any future international rules.14

sources of methane (Ch 4 ) in grazing ruminantsCh 4Ch 4Ch 4typically 5-8% of energy in food is lost as enteric methane.What about the carbon s<strong>to</strong>red in my soil?Soils s<strong>to</strong>re large amounts of carbon. However, since the Kyo<strong>to</strong> Pro<strong>to</strong>col compares everything back <strong>to</strong> a base year(1990), the issue for New Zealand is whether the amount of carbon s<strong>to</strong>red under pas<strong>to</strong>ral soils is higher or lower thanthe base year. If we have increases in soil carbon, then we are effectively removing it from the atmosphere and we willget credit for it. But if soil carbon declines, we are effectively releasing it back in<strong>to</strong> the atmosphere and will thereforeincur a liability.There is a lot of uncertainty in this country as <strong>to</strong> whether pas<strong>to</strong>ral soils are gaining or losing carbon. We’re workingunder the assumption that pas<strong>to</strong>ral soils are not doing either and have opted not <strong>to</strong> account for carbon changes undersoil as part of our Kyo<strong>to</strong> commitment.So New Zealand won’t gain any credit for increases in pas<strong>to</strong>ral soil carbon, but we also won’t incur liabilities associatedwith decreases. Research is continuing <strong>to</strong> improve our understanding of soil carbon dynamics, which includesinvestigating the potential for a new product, bio-char, <strong>to</strong> boost the quantity of carbon s<strong>to</strong>red in pas<strong>to</strong>ral soils.Why doesn’t the carbon absorbed by pasture plants on dairy farms countas part of the farm emissions balance?Plants absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during pho<strong>to</strong>synthesis, capturing carbon and energy in plantmaterial. However, half the carbon absorbed is released back in<strong>to</strong> the atmosphere through plant respiration. A furtherquarter of the carbon absorbed is released back <strong>to</strong> the atmosphere via the decomposition of plant and root material.And the remainder is contained in leaves eaten by the cow. So rather than being s<strong>to</strong>red in the pasture, carbon is cycledaround from the atmosphere, in<strong>to</strong> the plant, and back <strong>to</strong> the atmosphere in a continuous process.The following table illustrates the working of carbon fluxes, the movement of carbon in and out of the atmosphereand carbon sinks (reservoirs that take in and s<strong>to</strong>re more carbon than they release).15

Carbon fluxes and Sinks/ha in a grazed pastureNew Zealand dairy (units t C/ha/year)20 <strong>to</strong>nnesfrom atmosphere as CO 2Gross pho<strong>to</strong>synthesis10 <strong>to</strong>nnesfrom atmosphere as CO 2Plant respirationNet pho<strong>to</strong>synthesis10 <strong>to</strong>nneConsumed by cows5 <strong>to</strong>nnePlant senescence& roots5 <strong>to</strong>nneCan planting trees in small areas, and along riparian margins, becounted <strong>to</strong> offset emissions?Trees can only be counted <strong>to</strong>wards the offsetting of emissions, under the current Kyo<strong>to</strong> rules, if they are in an areagreater than one hectare, which is at least 30 metres wide, and were planted after 1990. Trees will gain carboncredits as they grow; however if they are harvested all of the credit accrued will be lost.<strong>Fonterra</strong> has been encouraging the Government <strong>to</strong> retain the flexibility <strong>to</strong> recognise riparian planting for its carbonabsorbingbenefits. The first Kyo<strong>to</strong> commitment period (2008 – 2012) is underway, but there is an opportunity forNew Zealand <strong>to</strong> negotiate for riparian plantings <strong>to</strong> be included in future international agreements.What is <strong>Fonterra</strong> doing <strong>to</strong> support its shareholders in this area?<strong>Fonterra</strong> is maintaining a close dialogue with the Government on the Emissions Trading Scheme, which will bereviewed before the end of 2011. We are committed <strong>to</strong> working <strong>to</strong> ensure that New Zealand’s climate changepolicy is practical, cost effective and well designed for both our farmers and New Zealand as a whole.We will continue <strong>to</strong> keep you, as shareholders, informed about the climate change debate, ways of reducinggreenhouse gas emissions and policy decisions as they arise, through articles in Farmlink and on Fencepost, andthrough contact at conferences and other events.What can dairy farmers do <strong>to</strong> reduce emissions?At present there are few known practical ways of reducing agricultural methane emissions, though we hope the researchwe are helping fund at the Pas<strong>to</strong>ral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium will come up with some solutions. In themeantime, there are ways of reducing carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions, many of which will also save money.By following a nutrient budget <strong>to</strong> work out your fertiliser requirements, you can limit nitrous oxide emissions fromfertiliser as well as saving money.Nitrification inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs lower nitrous oxide emissions and reduce nitrate leaching in<strong>to</strong> waterways, and can increasepasture growth. Trials show 30-70 per cent reductions in nitrous oxide production in some regions and under idealconditions. Together with Government and our industry partners we are funding research <strong>to</strong> find out how effectivenitrification inhibi<strong>to</strong>rs are under different soil types and conditions.Energy improvements in the farm dairy can reduce expenditure on electricity as well as cut carbon dioxide emissions.Ways of reducing energy on-farm include:• Optimising milk vat refrigeration• Insulating hot water cylinders• Maintaining milking vacuum pumps.You can find out more about energy savings on-farm on Fencepost.16

For more information contact.<strong>Fonterra</strong> Co-operative Group LimitedPrivate Bag 92032, Auckland<strong>Fonterra</strong> Centre, 9 Princes StreetAuckland, New ZealandPh 09 374 9000Fax 09 374 9001www.fonterra.comThis booklet is printed usingvegetable inks on FSC mixedsource certified recycled paper.