Issue 67 - British Neuroscience Association

Issue 67 - British Neuroscience Association

Issue 67 - British Neuroscience Association

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

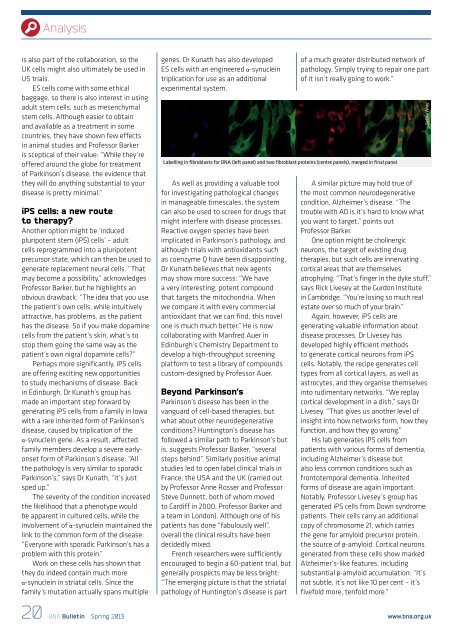

Analysisis also part of the collaboration, so theUK cells might also ultimately be used inUS trials.ES cells come with some ethicalbaggage, so there is also interest in usingadult stem cells, such as mesenchymalstem cells. Although easier to obtainand available as a treatment in somecountries, they have shown few effectsin animal studies and Professor Barkeris sceptical of their value: “While they’reoffered around the globe for treatmentof Parkinson’s disease, the evidence thatthey will do anything substantial to yourdisease is pretty minimal.”iPS cells: a new routeto therapy?Another option might be ‘inducedpluripotent stem (iPS) cells’ – adultcells reprogrammed into a pluripotentprecursor state, which can then be used togenerate replacement neural cells. “Thatmay become a possibility,” acknowledgesProfessor Barker, but he highlights anobvious drawback. “The idea that you usethe patient’s own cells, while intuitivelyattractive, has problems, as the patienthas the disease. So if you make dopaminecells from the patient’s skin, what’s tostop them going the same way as thepatient’s own nigral dopamine cells?”Perhaps more significantly, iPS cellsare offering exciting new opportunitiesto study mechanisms of disease. Backin Edinburgh, Dr Kunath’s group hasmade an important step forward bygenerating iPS cells from a family in Iowawith a rare inherited form of Parkinson’sdisease, caused by triplication of theα-synuclein gene. As a result, affectedfamily members develop a severe earlyonsetform of Parkinson’s disease: “Allthe pathology is very similar to sporadicParkinson’s,” says Dr Kunath, “it’s justsped up.”The severity of the condition increasedthe likelihood that a phenotype wouldbe apparent in cultured cells, while theinvolvement of α-synuclein maintained thelink to the common form of the disease:“Everyone with sporadic Parkinson’s has aproblem with this protein.”Work on these cells has shown thatthey do indeed contain much moreα-synuclein in striatal cells. Since thefamily’s mutation actually spans multiplegenes, Dr Kunath has also developedES cells with an engineered α-synucleintriplication for use as an additionalexperimental system.Labelling in fibroblasts for DNA (left panel) and two fibroblast proteins (centre panels), merged in final panel.As well as providing a valuable toolfor investigating pathological changesin manageable timescales, the systemcan also be used to screen for drugs thatmight interfere with disease processes.Reactive oxygen species have beenimplicated in Parkinson’s pathology, andalthough trials with antioxidants suchas coenzyme Q have been disappointing,Dr Kunath believes that new agentsmay show more success: “We havea very interesting, potent compoundthat targets the mitochondria. Whenwe compare it with every commercialantioxidant that we can find, this novelone is much much better.” He is nowcollaborating with Manfred Auer inEdinburgh’s Chemistry Department todevelop a high-throughput screeningplatform to test a library of compoundscustom-designed by Professor Auer.Beyond Parkinson’sParkinson’s disease has been in thevanguard of cell-based therapies, butwhat about other neurodegenerativeconditions? Huntington’s disease hasfollowed a similar path to Parkinson’s butis, suggests Professor Barker, “severalsteps behind”. Similarly positive animalstudies led to open label clinical trials inFrance, the USA and the UK (carried outby Professor Anne Rosser and ProfessorSteve Dunnett, both of whom movedto Cardiff in 2000, Professor Barker anda team in London). Although one of hispatients has done “fabulously well”,overall the clinical results have beendecidedly mixed.French researchers were sufficientlyencouraged to begin a 60-patient trial, butgenerally prospects may be less bright:“The emerging picture is that the striatalpathology of Huntington’s disease is partof a much greater distributed network ofpathology. Simply trying to repair one partof it isn’t really going to work.”A similar picture may hold true ofthe most common neurodegenerativecondition, Alzheimer’s disease. “Thetrouble with AD is it’s hard to know whatyou want to target,” points outProfessor Barker.One option might be cholinergicneurons, the target of existing drugtherapies, but such cells are innervatingcortical areas that are themselvesatrophying. “That’s finger in the dyke stuff,”says Rick Livesey at the Gurdon Institutein Cambridge. “You’re losing so much realestate over so much of your brain.”Again, however, iPS cells aregenerating valuable information aboutdisease processes. Dr Livesey hasdeveloped highly efficient methodsto generate cortical neurons from iPScells. Notably, the recipe generates celltypes from all cortical layers, as well asastrocytes, and they organise themselvesinto rudimentary networks. “We replaycortical development in a dish,” says DrLivesey. “That gives us another level ofinsight into how networks form, how theyfunction, and how they go wrong.”His lab generates iPS cells frompatients with various forms of dementia,including Alzheimer’s disease butalso less common conditions such asfrontotemporal dementia. Inheritedforms of disease are again important.Notably, Professor Livesey’s group hasgenerated iPS cells from Down syndromepatients. Their cells carry an additionalcopy of chromosome 21, which carriesthe gene for amyloid precursor protein,the source of β-amyloid. Cortical neuronsgenerated from these cells show markedAlzheimer’s-like features, includingsubstantial β-amyloid accumulation: “It’snot subtle, it’s not like 10 per cent – it’sfivefold more, tenfold more.”Selina Wray20 BNA Bulletin Spring 2013www.bna.org.uk