A Tale of Two Cars - Miller Thomson

A Tale of Two Cars - Miller Thomson

A Tale of Two Cars - Miller Thomson

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

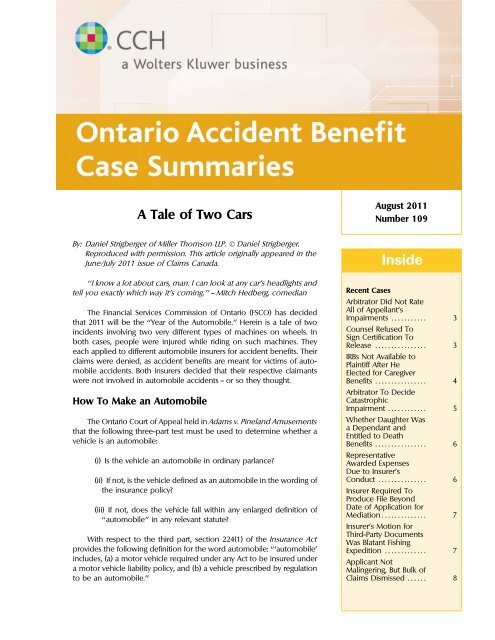

August 2011A <strong>Tale</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Two</strong> <strong>Cars</strong> Number 109By: Daniel Strigberger <strong>of</strong> <strong>Miller</strong> <strong>Thomson</strong> LLP. © Daniel Strigberger.Reproduced with permission. This article originally appeared in theJune/July 2011 issue <strong>of</strong> Claims Canada.Inside‘‘I know a lot about cars, man. I can look at any car’s headlights andtell you exactly which way it’s coming.’’ — Mitch Hedberg, comedianRecent CasesArbitrator Did Not RateThe Financial Services Commission <strong>of</strong> Ontario (FSCO) has decided All <strong>of</strong> Appellant’sImpairments ........... 3that 2011 will be the ‘‘Year <strong>of</strong> the Automobile.’’ Herein is a tale <strong>of</strong> twoincidents involving two very different types <strong>of</strong> machines on wheels. In Counsel Refused ToSign Certification Toboth cases, people were injured while riding on such machines. TheyRelease ................ 3each applied to different automobile insurers for accident benefits. TheirIRBs Not Available toclaims were denied, as accident benefits are meant for victims <strong>of</strong> auto-Plaintiff After Hemobile accidents. Both insurers decided that their respective claimants Elected for Caregiverwere not involved in automobile accidents — or so they thought. Benefits ................ 4How To Make an AutomobileArbitrator To DecideCatastrophicImpairment ............ 5The Ontario Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal held in Adams v. Pineland Amusements Whether Daughter Wasthat the following three-part test must be used to determine whether aa Dependant andEntitled to Deathvehicle is an automobile: Benefits ................ 6(i) Is the vehicle an automobile in ordinary parlance?RepresentativeAwarded ExpensesDue to Insurer’sConduct ............... 6(ii) If not, is the vehicle defined as an automobile in the wording <strong>of</strong>the insurance policy?Insurer Required ToProduce File BeyondDate <strong>of</strong> Application forMediation.............. 7(iii) If not, does the vehicle fall within any enlarged definition <strong>of</strong>‘‘automobile’’ in any relevant statute?Insurer’s Motion forThird-Party DocumentsWith respect to the third part, section 224(1) <strong>of</strong> the Insurance ActWas Blatant Fishingprovides the following definition for the word automobile: ‘‘‘automobile’ Expedition ............. 7includes, (a) a motor vehicle required under any Act to be insured underApplicant Nota motor vehicle liability policy, and (b) a vehicle prescribed by regulation Malingering, But Bulk <strong>of</strong>to be an automobile.’’ Claims Dismissed ...... 81

3Ontario Accident Benefit Case Summariesmotor vehicle under the Highway Traffic Act because it is a‘‘vehicle propelled or driven otherwise than by muscularpower.’’ Therefore, while on the road it would also requireauto insurance, pursuant to the Compulsory AutomobileInsurance Act, and, accordingly, it would be considered tobe an automobile under the Insurance Act. Go Diego Go!RECENT CASESAppealsArbitrator Did Not Rate All <strong>of</strong> Appellant’sImpairmentsThe appellant appealed an arbitrator’s decision thatfound she had not sustained a catastrophic impairment.The appellant raised 135 alleged errors <strong>of</strong> law. Much <strong>of</strong> herappeal focused on the arbitrator’s weighing <strong>of</strong> the evi-dence and specific findings <strong>of</strong> fact. More specifically, theappellant submitted that her whole person impairment(‘‘WPI’’) was 75% (the arbitrator had found 28%). The arbi-trator had also found that the appellant’s upper leftextremity impairment and knee impairment were notassessable because they had not yet stabilized.The appeal was allowed in part: the special award wasrescinded; the insurer was required to pay the applicant$3,250 with interest; and the applicant was to provide awitnessed release. The Director’s Delegate noted that bothcounsel submitted their personal beliefs as to the usual,standard, known, common, appropriate, and reasonablepr<strong>of</strong>essional and business practice <strong>of</strong> the industry and barregarding releases, but aside from those personal beliefs,the arbitrator had little or no proper evidence before her asto the common practice <strong>of</strong> releases generally, and the cer-tification issue specifically. In that regard, the insurer con-ceded that a lawyer’s certification regarding explaining theramification <strong>of</strong> the release breached solicitor–client privilege.On the other hand, the Director’s Delegate found thatone could take judicial notice <strong>of</strong> the fact that having awitness to a contractual signature was reasonable andcommonplace. With respect to the special award, theDirector’s Delegate found that the arbitrator ordered it onthe principle that the insurer arbitrarily added an additionalrequirement that was not statutorily mandated. TheDirector’s Delegate concluded that the arbitrator erred inthis regard. If the documents were not accepted, then theparties were obliged to further discussion, keeping in mindthe overriding legislative objective <strong>of</strong> resolving disputesfairly and efficiently. The Director’s Delegate rescinded thearbitrator’s special award.The appeal was allowed and the issue <strong>of</strong> catastrophicimpairment was returned to arbitration for a new hearing.The Director’s Delegate agreed with the appellant that allareas <strong>of</strong> impairment should be readdressed, as there wasan overlap between impairments that were not rated andones that were. The Director’s Delegate noted that appealsfrom an arbitrator’s order are limited to questions <strong>of</strong> law;therefore, the appellant’s submissions about the evidencewould be left to the arbitrator rehearing the matter. TheDirector’s Delegate found that the arbitrator erred in law innot rating the appellant’s left upper extremity and kneeimpairments. The Director’s Delegate also held that afinding <strong>of</strong> catastrophic impairment does not by itself resultin compensation; each benefit claim must still meet specificstatutory requirements. He found that the two-yearprovision in subsection 2(2.1) <strong>of</strong> the Statutory AccidentBenefits Schedule and the two-year non-catastrophicimpairment limit on attendant care were not merely coin-cidence: the legislative intent is a timely catastrophic deter-mination that allows for a continuity <strong>of</strong> benefits. Paragraph2(1.2)(f) <strong>of</strong> the Schedule states that impairments are to berated in accordance with the Guides to the Evaluation <strong>of</strong>Permanent Impairment (the ‘‘Guides’’), but the timing <strong>of</strong>all assessments are determined by subsection 2(2.1), towhich the Guides must defer. The arbitrator also erred indetermining that neither a sleep disorder nor chronic paincould be rated separately.Bains v. RBC General Insurance Company, SummaryNo. A-0976 (FSCO)Counsel Refused To Sign Certification ToReleaseThe appeal raised an important and novel question: ifthe parties settled a dispute with respect to accident benefits,what were the ramifications <strong>of</strong> a dispute over the execution<strong>of</strong> the release? The applicant’s counsel refused tosign a certification that he properly advised his client <strong>of</strong> thelegal ramifications <strong>of</strong> the release, and also refused to witnessit personally. He did send an executed consent todismissal and a draft order. Correspondence ensued andultimately the applicant requested the matter be relistedfor arbitration, with a preliminary issue hearing on the settlementissue. The applicant submitted he had providedeverything required for a settlement. Arbitrator Killoranagreed with the applicant, and found the insurer wasunreasonable to a flagrant degree, awarding a specialaward. The insurer appealed.Dominion <strong>of</strong> Canada General Insurance Companyv. Singh, Summary No. A-0977 (FSCO)

Ontario Accident Benefit Case Summaries 4Fund Relied to Its Detriment on PriorCommon Lawthe respondent had a marked impairment in the activities<strong>of</strong> daily living due to mental or behavioural disorder, andmoderate impairment in three remaining areas <strong>of</strong> functioning.The marked impairment in the activities <strong>of</strong> dailyliving was the basis for the finding <strong>of</strong> catastrophic impair-ment. The Director’s Delegate, in response to the submis-sion <strong>of</strong> the failure to attribute the limitations suffered by therespondent to physical impairment or associated pain,held that the arbitrator’s determination that herbehavioural and mental disorders resulted in a Class 4impairment was a finding <strong>of</strong> fact. The Director’s Delegateconcluded it was not his role to second-guess the arbitrator’sevaluation <strong>of</strong> the evidence.In May 2005, while driving an uninsured vehiclebelonging to a friend, the claimant suffered serious injuriesin a single-vehicle accident. An adjuster acting on behalf <strong>of</strong>the Motor Vehicle Accident Claims Fund (the ‘‘Fund’’)attempted to determine if the claimant was listed under hisemployer’s automobile insurance policy. After severalmonths, in November 2005, the employer finally sent acopy <strong>of</strong> its insurance policy to the Fund. A week later, theFund adjuster sent the employer’s insurer a Notice toApplicant <strong>of</strong> Dispute Between Insurers because this wastypical practice. The insurer placed the file in abeyancepending the decision in Allstate Insurance Co. <strong>of</strong> Canada v.Motor Vehicle Accident Claims Fund, 2007 ONCA 61, inwhich the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal ultimately held that the Fundwas an ‘‘insurer’’ and was bound by the notice provisions.At arbitration, the insurer argued that the Fund failed todeliver its notice within the 90-day period pursuant to O.Reg. 283/95 (the ‘‘Regulation’’). However, the arbitratorfound that the Fund was not bound by the notice provisionsin the Regulation. The insurer appealed.The appeal was dismissed. The Court noted that thedispute between the Fund and the insurer arose duringvarious common law developments. In Ontario (Minister<strong>of</strong> Finance) v. Progressive Casualty Insurance Co. <strong>of</strong>Canada, 2009 ONCA 258, the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal held that thedecision in Allstate applied retrospectively except in caseswhere there is clear evidence <strong>of</strong> detrimental reliance onthe prior common law rule. The Court concluded that theProgressive decision intended a party to be exemptedfrom the new law in Allstate where it could show it clearlyand detrimentally relied on the previous authority; anyother interpretation <strong>of</strong> Progressive would be contrary tothe scheme <strong>of</strong> the Insurance Act. The Court concluded theFund did rely to its detriment on the existing common lawauthority at the time <strong>of</strong> its investigation, and the Allstatedecision did not apply in the circumstances.Ontario (Minister <strong>of</strong> Finance) v. Lombard General Insurance,Summary No. A-0979 (Ont. S.C.J.)The application for judicial review was granted and thedecision <strong>of</strong> the Director’s Delegate was set aside. The Courtheld that the assessment <strong>of</strong> mental/behavioural disordersrequires consideration <strong>of</strong> all four areas <strong>of</strong> functioning. TheDirector’s Delegate erred in not considering the effect <strong>of</strong>the American Medical Association’s Guides to the Evalua-tion <strong>of</strong> Permanent Impairment (the ‘‘Guides’’) on the StatutoryAccident Benefits Schedule. The Court held that theDirector’s Delegate interpreted the Guides as if they had norelationship to the Schedule. The Court found that thecases relied on by the arbitrator and the Director’s Delegatewere informative, but not determinative <strong>of</strong> the issue.The Court also held that the Director’s Delegate failed toconsider the guidelines published by the province asexternal aids to understanding the Guides. The Court concludedthat, while it was possible for a finding <strong>of</strong> cata-strophic impairment to be dominated by one <strong>of</strong> the fourareas <strong>of</strong> functioning, the requirement was that all four areas<strong>of</strong> functioning must be considered when making an assessment.Matlow J., while agreeing with the result, dissented onthe first issue, finding that nothing in the Guides requiredmore than a single finding. Matlow J. also disagreed that theGuides were a part <strong>of</strong> the legislation.Aviva Canada Inc. v. Pastore, Summary No. A-0980 (Ont.Div. Ct.)All Four Areas <strong>of</strong> Functioning To BeConsidered When Making AssessmentThe plaintiff, who had been injured in an automobileaccident, was entitled to two types <strong>of</strong> statutory benefits:income replacement benefits (‘‘IRBs’’) and caregiver bene-fits (‘‘CGBs’’). He elected for the latter, and then commencedan action for, among other things, past incomeloss. Subsection 267.8(1) <strong>of</strong> the Insurance Act (the ‘‘Act’’)provides that statutory accident benefits are deductiblefrom personal injury damages arising from the use <strong>of</strong> anThe insurer applied for judicial review <strong>of</strong> a dismissal bythe Director’s Delegate <strong>of</strong> its appeal from an arbitrator’sdecision confirming a Designated Assessment Centre’s(‘‘DAC’’) assessment that the respondent suffered a catastrophicimpairment due to mental/behavioural disorder.The respondent suffered a fractured ankle and had kneereplacement surgeries. A DAC assessment determined thatIRBs Not Available to Plaintiff After HeElected for Caregiver Benefits

5Ontario Accident Benefit Case Summariesautomobile. A pre-trial determination held that the IRBs the applicant, except when he was sedated. The Ambuwere‘‘available’’ to the plaintiff, despite his election for lance Call Report, written by the paramedics who took theCGBs, and were therefore deductible from any potential imbedded person from the scene, indicated a score <strong>of</strong> 13damages award. The plaintiff appealed.for him. <strong>Two</strong> other paramedics who triaged the injured atthe scene testified that they were not required to make aThe appeal was allowed. The Court noted that the written record, but that they conducted a GCS test andpurpose <strong>of</strong> subsection 267.8(1) <strong>of</strong> the Act is to prevent assigned a score <strong>of</strong> 3 to the imbedded person.double recovery, and that subsection 36(1) <strong>of</strong> the StatutoryAccidents Benefits Schedule permits a person to receive The applicant was the passenger found imbedded inonly one <strong>of</strong> IRBs, CGBs, or non-earner benefits. The defend- the hillside, but he did not sustain a catastrophic impairantsargued that once the plaintiff chose not to apply for ment within the meaning <strong>of</strong> subparagraph 2(1.1)(e)(i) <strong>of</strong> theIRBs, despite the fact that they were available to him, he Schedule. The arbitrator held that, based on statements,had to bear the consequences <strong>of</strong> that decision. The Courtreports, and records, the applicant was the personfound that this argument ignored two issues. First, itimbedded in the hillside. The medical description <strong>of</strong> thatignored the fact that the legislation required the plaintiff topatient was in accord with the paramedics’ memory. Howmakea decision, and once he elected CGBs, IRBs were noever, with respect to the GCS score, the arbitrator conlongeravailable to him. Second, it ignored the ‘‘preventioncluded that the paramedics did not administer a GCS test<strong>of</strong> double recovery’’ purpose <strong>of</strong> subsection 267.8(1) andon site; he did not accept their evidence in this regard. Theactually resulted in undercompensation to the defendants’arbitrator held that, while he did not doubt their sincerity,windfall. To accept the defendants’ argument would meanhe did not accept that they had total recall <strong>of</strong> all the detailsthat they were entitled to the credit for both CGBs (whichnine years after the accident. In addition, the arbitratorthe plaintiff received) and IRBs (which he did not receive).noted that, as the standards did not require the triage unitThe Court concluded that once the plaintiff elected CGBs,to administer a GCS test, it was less likely that theIRBs were no longer available to him.paramedics did so. As such, there was no GCS score <strong>of</strong> 9 orSutherland v. Singh, Summary No. A-0981 (Ont. C.A.)less recorded for the applicant. The arbitrator concludedthat there was no evidence upon which he could find thatthe applicant’s brain impairment caused or contributed tothe GCS scores upon which he relied in this arbitration.● ExpensesOther Appeal DecisionsWindsor v. Motor Vehicle Accident Claims Fund, SummaryNo. 11342 (FSCO)Piche v. Allstate Insurance Company <strong>of</strong> Canada, SummaryNo. A-0978 (FSCO)● Request for Variation OrderBerger v. Gore Mutual Insurance Company, SummaryNo. A-0982 (FSCO)CasesDetermining Catastrophic ImpairmentThe issue before the arbitrator was whether the appli-cant sustained a catastrophic impairment. The applicantwas in a horrific single-vehicle accident where all six occu-pants were ejected from the vehicle and only one wasidentified at the scene. The applicant maintained he wasthe person who was found imbedded in the hillside andthat his Glascow Coma Scale (‘‘GCS’’) score was 9 or less,which indicates catastrophic impairment according to theStatutory Accident Benefits Schedule (the ‘‘Schedule’’).There was no written record <strong>of</strong> a GCS score <strong>of</strong> 9 or less forArbitrator To Decide CatastrophicImpairmentAfter the applicant was awarded various statutory accidentbenefits, he applied for a determination <strong>of</strong> catastrophicimpairment. The parties were unable to resolvethe precise scope <strong>of</strong> the issue to be put before the arbitratorand requested a preliminary ruling. The preliminaryissue here was whether the issue <strong>of</strong> causation for the purpose<strong>of</strong> determining a catastrophic impairment hadalready been decided. The case had a long and complexprocedural history. Technically, the issue in dispute was theprocedural impact <strong>of</strong> Arbitrator Killoran’s decision <strong>of</strong> July 7,2005, in which she awarded the applicant benefits but didnot deal with the issue <strong>of</strong> catastrophic impairment, as thatissue was not before her. Prior to the applicant’s death, acatastrophic impairment Designated Assessment Centre(‘‘CAT DAC’’) assessment found 87% whole person impair-ment, but also opined 0% was related to the accident. Theapplicant argued the issue <strong>of</strong> causation was res judicata, asit was covered by the doctrine <strong>of</strong> estoppel.

Ontario Accident Benefit Case Summaries 6The issue to be put before the arbitrator was: Was the cluded that the applicant did not have the mental capacityapplicant catastrophically impaired as a result <strong>of</strong> the acci- to proceed in the dispute resolution process. After findingdent on July 12, 2001? The arbitrator summed up the pro- no suitable attorney or person to act on behalf <strong>of</strong> thecedural quandary: on the one hand was an arbitrator’s applicant, the arbitrator stated he would forward a copy <strong>of</strong>decision, confirmed by appeal and judicial review, that the this decision to the Public Guardian and Trustee.applicant’s impairments were accident-related and notsimply the result <strong>of</strong> pre-existing conditions; but on the Mr. S v. Aviva Canada Inc., Summary No. 11346 (FSCO)other hand were CAT DAC assessments that found theapplicant met the test for catastrophic impairment, yet disagreedthese impairments were accident-related. The arbi- Whether Daughter Was a Dependant andtrator concluded that the issue <strong>of</strong> causation, solely as itEntitled to Death Benefitsrelated to whole person impairment, was not yet adjudicated.The arbitrator held that it was possible for an adjudi- The applicant was the daughter <strong>of</strong> the deceasedcator to find someone with pre-existing conditions to be insured. The issue was whether she was entitled to a deathentitled to benefits but also not be catastrophically benefit as a dependant <strong>of</strong> the insured. The applicant wasimpaired as a result <strong>of</strong> the accident. While the general issue enrolled in school. The accident occurred in August 2006,<strong>of</strong> causation was dealt with by Arbitrator Killoran, the cata- and the parties agreed to focus on the year preceding thestrophic impairment definitions in the Schedule raised the accident in determining whether the applicant was finanissue<strong>of</strong> causation in a way not completely captured by a cially dependent on her father.finding that a motor vehicle accident contributed to aperson’s disability or need for medical treatment so as to The applicant was a dependant and was entitled to aentitle the person to accident benefits. The arbitrator death benefit. The arbitrator found the applicant credible;noted that the ultimate purpose <strong>of</strong> arbitration is to provide her testimony made sense and coincided with the orala fair hearing to both parties; the insurer was entitled to a evidence <strong>of</strong> other witnesses. The arbitrator concluded thatfair hearing and to be allowed to argue its case.the evidence as a whole established a relationship <strong>of</strong> financialdependence between the applicant and her fatherKanareitsev (Estate) v. TTC Insurance Company, Summary during the year in question. The arbitrator stated that herNo. 11344 (FSCO) conclusion rested on an assessment <strong>of</strong> the applicant’sexpenses and income. For example, the applicant was onlyable to work part-time, which indicated an inability to beself-supporting. The arbitrator held that the student loanApplicant Did Not Understand Arbitrationwas not to be viewed as income, as the applicant’s fatherProcessintended to pay <strong>of</strong>f the loan for her (he had put his car upfor sale to help pay the student loan). The arbitrator alsoThe preliminary issue before the arbitrator wasfound that the insured made a car available to his daughterwhether the applicant was a party under disability pursuantand paid her rent almost all <strong>of</strong> the time. The arbitratorto Rule 10 <strong>of</strong> the Dispute Resolution Practice Code. Inconcluded the applicant could only pay one-third <strong>of</strong> heraddition to stating that he did not understand the proexpenseson her own.ceedings, the applicant chose not to listen to medical testimonyabout him, saying he could not ‘‘be in the samePoutney v. Economical Mutual Insurance, Summaryroom with two doctors who don’t tell the truth’’.No. 11356 (FSCO)The applicant was injured in an accident, and the arbi-trator ruled on his claims for statutory accident benefits,reserving on the expenses issue. The insurer sought anorder that Alon Rooz be made a party to the proceedingsand that he personally pay all or part <strong>of</strong> the expensesawarded to the insurer. Rooz consented, but then movedfor summary judgment to dismiss the insurer’s claimregarding his personal liability. In the meantime, theDirector’s Delegate dismissed the applicant’s appeal <strong>of</strong> theThe applicant was a party under a disability. The arbitratorfound that the applicant was extremely confusedand not able to focus on the proceeding. Despite repeatedreminders as to the nature <strong>of</strong> the proceeding, it was neverclear to the arbitrator that the applicant understood. Thearbitrator noted that the applicant was continually interruptive,and seemed uncomfortable and apprehensive.The arbitrator noted that a medical pr<strong>of</strong>essional found theapplicant was unable to stay focused, and the inability tocomplete the mini mental status examination likely signifieda hyperactive attention deficit disorder. The arbitratorfound this evidence compelling and overrode the presumptionthat the applicant had the requisite capacity toproceed with the arbitration process. The arbitrator con-Representative Awarded Expenses Due toInsurer’s Conduct

7Ontario Accident Benefit Case SummariesThe applicant was to pay the insurer’s expenses <strong>of</strong> thearbitration hearing. The insurer was to pay $500 to Rooz forthe motion for summary judgment. The insurer was notpermitted to set <strong>of</strong>f its expenses award against theexpenses it was to pay to Rooz. In applying the criteria setout in what is commonly known as the Expense Regula-tion, the arbitrator found that the insurer was entirely suc-cessful at arbitration, and that none <strong>of</strong> the other factorswere particularly relevant. As such, the insurer was entitledto expenses. However, given the overall simplicity <strong>of</strong> thehearing, the amount <strong>of</strong> preparation time sought by theinsurer was not reasonable, nor did the insurer requiredouble legal representation. The arbitrator concluded thatthe insurer was entitled to $4,509.22 <strong>of</strong> the approximately$28,000 it claimed. With respect to the summary judgmentmotion, the arbitrator noted the insurer presented no evi-dence to support its claim to have a representative madepersonally liable. The arbitrator found the insurer’s conductunreasonable and, given Rooz’s success, awarded himexpenses. However, the arbitrator found that Rooz’s claimfor legal fees was excessive, especially since much <strong>of</strong> theargument presented resembled Seyed v. Federated InsuranceCompany <strong>of</strong> Canada, where an order for expenseswas sought against another member <strong>of</strong> Rooz’s firm. Thearbitrator fixed Rooz’s expenses at $500 and awarded thisamount. Finally, the arbitrator found that the possibility theinsurer would be unable to recover from the applicant didnot justify an <strong>of</strong>fset <strong>of</strong> Rooz’s award, who was a distinct anddifferent party.Abbas v. Security National Insurance Co./MonnexInsurance Mgmt., Summary No. 11364 (FSCO)Insurer Required To Produce File BeyondDate <strong>of</strong> Application for MediationThe insurer and the applicant disputed her entitlementto housekeeping and home maintenance benefits. In thismotion, the issue was whether the insurer was required toproduce its file beyond the date <strong>of</strong> the application formediation and, if so, whether production was limited tothe portion <strong>of</strong> the file related to housekeeping and homemaintenance benefits or whether the entire file wasrequired. The insurer had agreed to produce its file up tothe application for mediation. The date stamp on theapplication for mediation was October 6, 2008, but FSCOnotified the insurer by letter dated January 2, 2009.arbitration order. The arbitrator granted Rooz’s motion forsummary judgment and dismissed the insurer’s motion. Atissue was which party was entitled to expenses in relationto both the arbitration hearing and the motion for sum-mary judgment.The insurer’s entire file was relevant, and it wasrequired to produce the file, subject to any privilege, to thedate <strong>of</strong> FSCO’s letter. The arbitrator found that there waseither a one-step or a two-step approach to determining iflitigation privilege arose, depending on the issue. Theone-step approach was used if there was only one issue indispute or if all the benefits claimed were in dispute. Thetwo-step approach applied where there were numerousbenefit claims, but with only one <strong>of</strong> those issues beingsubject to a reasonable apprehension <strong>of</strong> litigation, suchthat the party seeking privilege bore the burden in thesecond step <strong>of</strong> showing that the documents were preparedin anticipation <strong>of</strong> litigation. Applying the first step,the arbitrator found it likely that in the circumstances <strong>of</strong> thesignificant delay by FSCO in notifying the insurer, theinsurer did not anticipate litigation until it received noticethat the applicant applied for mediation. The second step,following receipt <strong>of</strong> the application for mediation, meantthat documents in the insurer’s file were dual-purposed:for settlement and defence/litigation. The aforementionedsignificant delay by the FSCO was the distinguishing featurefor the arbitrator’s departure from previous FSCO arbitrator’sdecisions that privilege commenced on the date <strong>of</strong>the application for mediation.Vaitheeswaran v. State Farm Mutual AutomobileInsurance Company, Summary No. 11365 (FSCO)Insurer’s Motion for Third-PartyDocuments Was Blatant Fishing ExpeditionIn a dispute over benefits, the insurer moved for anorder that the Children’s Aid Society <strong>of</strong> Toronto (‘‘CAS’’)produce an unredacted copy <strong>of</strong> its records in respect <strong>of</strong>the applicant’s children. The applicant, who continued toreceive income replacement benefits as a result <strong>of</strong> his accident,had been hospitalized with suicidal ideation. The CASbecame involved and investigated. The insurer argued thisinformation related to the family dynamics and, therefore,the applicant’s functionality. The insurer also relied on aletter from the applicant’s counsel implying that late productionswould be acceptable and on the fact that theapplicant also made late productions. The applicantopposed the motion, submitting, among other things, thatthe insurer’s CAS record request was made the nightbefore the hearing and such lateness was prejudicial tohim. In addition, the applicant raised confidentiality con-cerns in respect <strong>of</strong> his wife and children. With respect to hiscounsel’s letter, the applicant argued its purpose was notto permit an ‘‘ambush’’ on the eve <strong>of</strong> the hearing withpreviously unraised issues.The motion was dismissed. The arbitrator scheduledwhat she thought was a valid motion for third-party pro-

9Ontario Accident Benefit Case Summaries● Removal <strong>of</strong> Counsel● ExpensesVadivelu v. RBC General Insurance Company, SummaryNo. 11352 (FSCO)● Special AwardYogesvaran v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance,Summary No. 11353 (FSCO)● Limitations to Various ClaimsRamalingam v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance,Summary No. 11354 (FSCO)● Whether ‘‘Accident’’ OccurredAzimi v. Economical Mutual Insurance Company, SummaryNo. 11355 (FSCO)Piche v. Allstate Insurance Company <strong>of</strong> Canada, SummaryNo. 11360 (FSCO)● Limitations/Bars to ClaimBlier v. Royal & SunAlliance Insurance Company <strong>of</strong>Canada, Summary No. 11361 (FSCO)● Failure to AttendAkasha v. Personal Insurance Company <strong>of</strong> Canada, SummaryNo. 11362 (FSCO)● Expenses● Failure To AttendRitchie v. West Elgin Mutual Insurance Company, SummaryNo. 11357 (FSCO)● Failure To AttendE.P. v. TTC Insurance Company Limited, SummaryNo. 11358 (FSCO)● Special AwardYogesvaran v. State Farm Mutual Automobile InsuranceCompany, Summary No. 11363 (FSCO)● Failure To AttendSaid v. Security National Insurance Co./Monnex InsuranceMgmt. Inc., Summary No. 11366 (FSCO)● Income Replacement BenefitsRodrigues v. Jevco Insurance Company, SummaryNo. 11359 (FSCO)Carr v. TD General Insurance Company, SummaryNo. 11368 (FSCO)

Ontario Accident Benefit Case Summaries 10