Space Requirements for Wheeled Mobility - University at Buffalo ...

Space Requirements for Wheeled Mobility - University at Buffalo ...

Space Requirements for Wheeled Mobility - University at Buffalo ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Table of ContentsExecutive Summary …………………………………………………………………….....… 6Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….... 14Guidelines and Standards………………………………………………………………….. 16Anthropometry and accessibility guidelines, Edward Steinfeld, Arch. D.. …………….... 16BS 8300 – The research behind the standard, Robert Feeney …………………….......... 17Compliance analysis <strong>for</strong> disabled access, Charles Han, John Kunz and Kincho Law, Ph.…………………………………………………………………………….…………..….. 17Working area of wheelchairs – Details about some dimensions th<strong>at</strong> are specified in ISO5, Johann Ziegler …………………………………………………………………. 18Development of Australian Standards and Unmet Research Needs, Murray Mountain. 19Anthropometric Research in Australia, Rodney Hunter……………………………………. 19Disability Discrimin<strong>at</strong>ion Act 1995, Donald MacDonald …………………………...........… 20Challenges with the ADAAG, Marsha Mazz ……………………………………………….. 20General Discussion of Guidelines and Standards ……….………………………………… 21Trends and Issues in Technologies ……………………………………………………… 22Trends and issues in wheeled mobility technologies, Rory Cooper, Ph.D., and RosemarCooper, M.P.T., A.T.P. …………………………………………………………. 22Trends and issues in pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m lifts, David Balmer ………………………......................... 24Demographics of <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> Users ……………………………………………… 26Trends and issues in disability d<strong>at</strong>a and demographics, Mitchell La Plante, Ph.D. …… 26Human Modeling of <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> Aid Use ………………………………………… 29Wheelchair simul<strong>at</strong>ion in virtual reality, Michael Grant, Ph.D. …………………………… 29Virtual reality and full-scale modeling – a large mixed reality system <strong>for</strong> particip<strong>at</strong>ory desRoy Davies, Elisabeth Delhom, Birgitta Mitchell, Ph.D., and Paule T<strong>at</strong>e…… 29<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 4

4. “Trends and issues in disability d<strong>at</strong>a and demographics” by Mitchell La Plante,Ph.D. Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences and the DisabilitySt<strong>at</strong>istics Center, <strong>University</strong> of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, San Francisco. This paperaddressed trends in disability d<strong>at</strong>a and demographics, including in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ionabout wheeled mobility user health, function, perceived disability, financialresources and unmet needs.Papers were distributed to <strong>at</strong>tendees prior to the workshop. Two to fourparticipants were assigned to each paper to serve as paper discussants in orderto promote discussion about the paper’s contents and direct discussion towardsrecommend<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>for</strong> the Board’s research agenda. All participants were giventhe opportunity to respond to the papers after the present<strong>at</strong>ions th<strong>at</strong> were madeby the authors during the Workshop.An intern<strong>at</strong>ional group of human factors and ergonomics researchers, standardsdevelopers, designers, and computer modelers, many whom <strong>at</strong>tended the 2001workshop, particip<strong>at</strong>ed in the follow-up meeting. Sixty-seven registeredparticipants from the United St<strong>at</strong>es, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia,Austria, Sweden, and The Netherlands took part. A list of registered participantsis given in the Appendix.The meeting began on Thursday evening, October 9 and concluded on S<strong>at</strong>urdayafternoon, October 11, 2003. In addition to the commissioned work, a number ofother topics were presented and discussed <strong>at</strong> the Workshop. These specificallyaddressed accessibility guidelines and standards, advancements in humanmodeling, and the Board’s preliminary plans <strong>for</strong> anthropometric research ofmobility aid users.Eight present<strong>at</strong>ions addressed accessibility guidelines and standards:• “Anthropometry and Accessibility Guidelines" by Edward Steinfeld• “The research behind the standard” by Robert Feeney• "Compliance analysis <strong>for</strong> disabled access" by Charles Han, John Kunz andKincho Law, Ph.D.• “Working area of wheelchairs – Details about some dimensions th<strong>at</strong> arespecified in ISO” by Johann Ziegler• "Development of Australian standards and unmet research needs" byMurray Mountain• "Anthropometric research in Australia" by Rodney Hunter• "Disability Discrimin<strong>at</strong>ion Act of 1995 (UK)" by Donald MacDonald, and• "Challenges with the ADAAG" by Marsha MazzSeveral others addressed human modeling of wheeled mobility aid users:• "Wheelchair simul<strong>at</strong>ion in virtual reality" by Michael Grant, Ph.D.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 7

• "Virtual reality and full scale modeling – a large mixed reality system <strong>for</strong>particip<strong>at</strong>ory design" by Roy Davies, Elisabeth Delhom and Birgitta Mitchell,Ph.D., and Paule T<strong>at</strong>e• HADRIAN Human Modeling Design Tool, Mark Porter, Ph.D.• Mannequin Pro Human Modeling Design Tool, Dan HeltThe final present<strong>at</strong>ion by Victor Paquet, Sc.D., described the Access Board’spreliminary plans <strong>for</strong> anthropometric research, “Long range research plans”. Thisincluded detailed plan of work <strong>for</strong> the collection of two- and three- dimensionalanthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a, human modeling, and maneuverability research developedby the IDEA Center/RERC on Universal Design <strong>at</strong> <strong>Buffalo</strong>. Participants provideddetailed feedback about the preliminary plans and offered recommend<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>for</strong>the Board’s research agenda.The in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion g<strong>at</strong>hered from the papers, present<strong>at</strong>ions, and discussions wasorganized into the following topics:1. Guidelines and Standards2. Trends and Issues in Technologies3. Demographics of <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> Users4. Human Modeling of <strong>Mobility</strong> Aid Use5. Anthropometric Research6. Access Board’s Preliminary Research AgendaA summary of the key points <strong>for</strong> each is given below.Guidelines and Standards• Anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a have historically been used to develop reach limits,recommend<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>for</strong> maneuvering clearances, grab bar loc<strong>at</strong>ion, and rampslope <strong>for</strong> ANSI and ADAAG.• The anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a typically used by designers is extremely outd<strong>at</strong>ed,with many of the d<strong>at</strong>a sources and tools developed in the 1970s or earlier.Since this time, there have been important changes in the physicalcharacteristics of the popul<strong>at</strong>ion, the demographics of the popul<strong>at</strong>ion and in thetechnologies used by wheeled mobility users.• Standardized methods of anthropometric study are needed <strong>for</strong> standardsdevelopment. A number of important anthropometric studies have beenrecently completed in the United St<strong>at</strong>es, Australia, United Kingdom andCanada, but these suffer from several important limit<strong>at</strong>ions. User groups,measurement methods, and research environments vary gre<strong>at</strong>ly from onestudy to the next, which makes comparing results or pooling results acrossstudies extremely difficult.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 8

• ISO standard 7176-5 provides a framework <strong>for</strong> ensuring th<strong>at</strong> consistentlanguage and measurement methods are used in d<strong>at</strong>a g<strong>at</strong>hering acrossmultiple sites. The ISO 7176-5 defines 35 dimensions, including occupiedlength, occupied width, occupied height, minimum space, turning diameter,reversing width, required width <strong>for</strong> angled corridor, required doorway entrywidth, required width <strong>for</strong> side exit and ramp angle.• Use of multiple approaches about the physical size, function and preference ofuser groups is needed in the development of design standards. For example,use of percentiles in univari<strong>at</strong>e analyses of even the key parameters alone donot provide a good estim<strong>at</strong>e of the percent of individuals capable ofsuccessfully maneuvering in a space, and there<strong>for</strong>e such limited analysesshould not be heavily weighted in standards development.• Another approach to development of guidelines involves the dissemin<strong>at</strong>ion of“Best Practices”. For example, Dave Rapson developed such a guide th<strong>at</strong>included recommend<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>for</strong> the design of environments to accommod<strong>at</strong>epowered scooters th<strong>at</strong> was developed by the Province of Manitoba and city ofWinnipeg.• Although simul<strong>at</strong>ion tools are very welcome <strong>for</strong> use in comparison of standardsand help bring the results to the designer and user, their use in thedevelopment of standards is not yet clear. The tools need to be valid<strong>at</strong>ed toinsure th<strong>at</strong> they reflect actual wheeled mobility behavior. Use of such tools willalso require new ways to interpret the d<strong>at</strong>a, an important element of thestandards development process.• The costs and benefits of space-requirements guidelines and standards arenot considered in a rigorous way across countries.Trends and Issues in Technologies• Only 20-25% of people worldwide who use wheeled mobility devices reportth<strong>at</strong> their mobility needs are met.• There is a high degree of variability in the turning radius and stability ofpowered wheelchairs. Those with rear-wheel drive typically have a largerturning radius, those with mid-wheel drive have a shorter turning radius but aremore susceptible to tipping, and those with front-wheel drive offer both a tightturning radius and stability, although they are more difficult to control duringstraight travel.• Market trends suggest th<strong>at</strong> the space requirements <strong>for</strong> wheeled mobility willincrease. For example, the market <strong>for</strong> both manual and powered “bari<strong>at</strong>ric” orhigh weight capacity chairs is expected to grow the most rapidly of all chairc<strong>at</strong>egories, and markets <strong>for</strong> PAPAW or power assisted chairs and specializedse<strong>at</strong>ing <strong>for</strong> chairs, although currently small, is expected to also grow rapidly.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 9

• Because environments are not standardized in their level of accommod<strong>at</strong>ion towheeled mobility needs, individuals who use wheeled mobility aids adapt by,<strong>for</strong> example, owning more than one wheeled-mobility device. On averagewheeled mobility users have two devices and 50% of wheeled mobility usersalso use a walker.• The U.S. Access Board has played an important role in ensuring th<strong>at</strong> theAMSE A18 standard appropri<strong>at</strong>ely addresses the needs of those who requirelifts.• The increasing size and weights associ<strong>at</strong>ed with newer powered mobilitydevices need to be considered in design standards.• While use of pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m lifts has vastly improved accessibility to the builtenvironment, their oper<strong>at</strong>ion can be difficult and time consuming. Ef<strong>for</strong>ts needto be devoted to universal design altern<strong>at</strong>ives th<strong>at</strong> elimin<strong>at</strong>e the need <strong>for</strong> lifts.Demographics of <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> Users• There are approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 2 million users of wheeled mobility users, and. trendssuggest th<strong>at</strong> this number may exceed 4 million users by 2010. This growth islikely due to changing social and technological trends, such as improvementsin the design of mobility aids, improved accessibility to devices, and socialacceptance of device use, r<strong>at</strong>her than an increased prevalence of disability orthe number of elderly people.• The effects of the growing aging popul<strong>at</strong>ion on the use of wheeled mobilitydevices are uncertain due, in part, to the limit<strong>at</strong>ions in the current n<strong>at</strong>ionalsurvey methods. However, those 65 and over make up 56% of the users ofwheeled mobility aids, and are more likely to use manual versus poweredmobility devices.• There are higher overall proportions of women who use wheeled mobilitydevices, particularly among the elderly. However, the number of male usersexceeds the number of women users among younger adults.• The device and environmental needs of wheeled mobility users in health carefacilities will need careful consider<strong>at</strong>ion in the future. When compared to nonwheeledmobility aid users, people who use wheeled mobility devices aremuch more likely to report poor health (40% compared to 2%), a gre<strong>at</strong>erfrequency of hospitaliz<strong>at</strong>ion and more frequent use of health care services.The most frequently reported building needs are usable doors and elev<strong>at</strong>ors,lifts and chair lifts <strong>for</strong> stairs.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 10

• Revisions to the n<strong>at</strong>ional surveys are needed to improve the quality and detailof in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion collected rel<strong>at</strong>ed to the frequency and severity disability andselection of assistive technologies. For example, the last NHIS-D survey didnot distinguish between powered or manual wheeled mobility-aid users.Additionally, n<strong>at</strong>ional surveys do not inquire about why a particular device wasselected and wh<strong>at</strong> altern<strong>at</strong>ives were considered.• The research community and sponsors are strongly encouraged to ensure thein<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about those with mobility impairments remains a priority and isimproved in future survey ef<strong>for</strong>ts.• A registry of wheeled mobility users could be developed from the surveyrespondents, provided th<strong>at</strong> the appropri<strong>at</strong>e consent could be obtained. Such aregistry could provide a value resource <strong>for</strong> future surveys designed to capturedetailed in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about barriers in design and factors th<strong>at</strong> affect theselection of wheeled mobility devices.Human Modeling of <strong>Mobility</strong> Aid Use• Digital human modeling packages such as HADRIAN are powerful design toolsin which a design can be evalu<strong>at</strong>ed against the body sizes and capabilities of“whole” virtual individuals r<strong>at</strong>her than individual dimensions (an importantlimit<strong>at</strong>ion of conventional anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a use). Based on the structuraland functional anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a, designers can test virtual tasks in virtualenvironments to determine the percentage of individuals who have the abilityto complete a task in the specific context of the environment.• An autom<strong>at</strong>ed prescriptive system <strong>for</strong> code-checking can be an extremelyvaluable design tool, but requires the designer to more completely define theobjects in CAD models. The Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Alliance of Interoperability (IAI) hasprovided a framework <strong>for</strong> defining sets of objects called Industry Found<strong>at</strong>ionClasses (IFC’s) th<strong>at</strong> support this object-oriented approach.• While digital human models and computer simul<strong>at</strong>ions are useful in design, it isnot clear if use of such tools will be of gre<strong>at</strong> value to the regul<strong>at</strong>ors. Typically,the design questions do not require the level of detail provided by digitalhuman models and simul<strong>at</strong>ions. Further discussion is needed to explore howdigital human modeling and simul<strong>at</strong>ion methods can be used effectively incode development.• Additionally, digital human models are only useful if they are valid<strong>at</strong>ed.Usually only components of the models (e.g., posture prediction <strong>for</strong> specifictasks) are evalu<strong>at</strong>ed, and there is not very much in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about the errorsassoci<strong>at</strong>ed with using digital human models in design.Anthropometric Research<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 11

• Overall, the preliminary research plans were well-received by Workshopparticipants. There was no criticism about the specific methods proposed inany of the projects summarized during the present<strong>at</strong>ion. Strengths identifiedby participants were the multi-site approach proposed in many of the projects,the inclusion of a variety of wheeled mobility devices, the emphasis onconsistent d<strong>at</strong>a g<strong>at</strong>hering methods, and the inclusion of both simple and highlysophistic<strong>at</strong>ed approaches.• The major limit<strong>at</strong>ion of the approach identified by some participants was thescope of the research plan. They argued th<strong>at</strong> to provide the in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ionneeded <strong>for</strong> standards development requires even gre<strong>at</strong>er numbers ofindividuals, a gre<strong>at</strong>er variety of individuals and a more in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion aboutfunctional task per<strong>for</strong>mance. Workshop participants also emphasized theneed <strong>for</strong> more work in the field versus the labor<strong>at</strong>ory.There were six major recommend<strong>at</strong>ions about the preliminary research agenda:1. Partner with other sponsors in the U.S. and other countries to expand theresearch plan. The current plan is a good start but much more needs to bedone. Use of anthropometry in the development of space requirements <strong>for</strong>standards requires th<strong>at</strong> all variables include demographic and devicecharacteristics are considered in the evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of the design parameter.2. Include field research activities designed to provide a better understanding ofthe most important environmental barriers in commercial and public buildings,as well as transport<strong>at</strong>ion systems.3. Ensure th<strong>at</strong> the plans <strong>for</strong> keeping d<strong>at</strong>a ef<strong>for</strong>ts consistent across multiple sitesare sound so th<strong>at</strong> d<strong>at</strong>a from these different sources can be combined.4. Ensure th<strong>at</strong> careful <strong>at</strong>tention continues is paid to the demographic variables,including the types of wheeled devices and c<strong>at</strong>egories of disability, so th<strong>at</strong>in<strong>for</strong>med design decisions can be made.5. Continue to explore the potential value of digital human modeling in spacerequirements <strong>for</strong> standards development.6. The experimental protocols used <strong>for</strong> this research agenda should be peerreviewedbe peered reviewed. A process should be developed to allow inputfrom an intern<strong>at</strong>ional group of stakeholders.In conclusion, the increasing prevalence of wheeled mobility device users and thetrends towards larger and heavier devices suggest th<strong>at</strong> the current spacerequirements <strong>for</strong> wheeled mobility accessibility need to be re-evalu<strong>at</strong>ed. Thecurrent research plans are a good start but more thought must be given to how toexpand the plan. It is likely th<strong>at</strong> a combin<strong>at</strong>ion of basic anthropometric research,<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 13

experimental trials, field observ<strong>at</strong>ions, and computer aided design analysis areneeded to provide the necessary in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about the physical size, function andpreference of user groups <strong>for</strong> the development of effective design standards.More discussion is needed to determine exactly how digital human modeling andsimul<strong>at</strong>ion can be used to in<strong>for</strong>m standards development.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 14

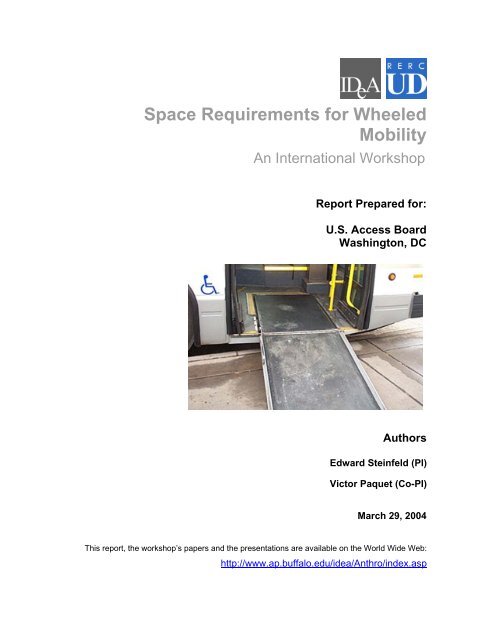

IntroductionGuidelines and other documents currently used in the United St<strong>at</strong>es in the courseof regul<strong>at</strong>ory activities incorpor<strong>at</strong>e dimensional d<strong>at</strong>a based on anthropometricsresearch conducted in the 1970’s (Steinfeld, et al, 1979). Simultaneously, newdevelopments in assistive technology, trends in rehabilit<strong>at</strong>ion practice, the ongoingdemographic shift toward an older society, and changes in st<strong>at</strong>ure of thepopul<strong>at</strong>ion due to nutritional improvements and genetic shifts suggest th<strong>at</strong> currentanthropometric d<strong>at</strong>abases themselves are no longer appropri<strong>at</strong>e <strong>for</strong> applic<strong>at</strong>ion incontemporary design. A study commissioned by the Access Board in 1997entitled Anthropometry <strong>for</strong> Persons with Disabilities: Needs <strong>for</strong> the 21 st Centuryconcluded th<strong>at</strong> available d<strong>at</strong>a no longer represent the range of the usingpopul<strong>at</strong>ion (Bradtmiller, 1997).In June 2001, a workshop titled "Anthropometrics of Disability" was held in <strong>Buffalo</strong>,NY to assess the st<strong>at</strong>e of the knowledge in anthropometric methods, d<strong>at</strong>acollection projects and human modeling ef<strong>for</strong>ts rel<strong>at</strong>ed to disability (Steinfeld, etal., 2002). The Workshop was underwritten by the US Access Board, with supportfrom the N<strong>at</strong>ional Institute on Disability and Rehabilit<strong>at</strong>ion Research through theRehabilit<strong>at</strong>ion Engineering Research Center on Universal Design <strong>at</strong> <strong>Buffalo</strong> andthe Rehabilit<strong>at</strong>ion Engineering Research Center on Workplace Ergonomics. The<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong> of the workshop was a series of paper present<strong>at</strong>ions and discussionsessions concluding with a final summary discussion session. Papers wereprepared prior to the Workshop and distributed to participants in printed <strong>for</strong>m. Allparticipants submitted written recommend<strong>at</strong>ions based on the discussions <strong>at</strong> eachpaper session. A summary report of the results of the Workshop was written.Both this document and the proceedings are available on the web site of theRERC on Universal Design <strong>at</strong> <strong>Buffalo</strong>. The workshop identified "gaps" in the st<strong>at</strong>eof knowledge about the collection, organiz<strong>at</strong>ion and applic<strong>at</strong>ion of anthropometricd<strong>at</strong>a as it rel<strong>at</strong>es to those with physical disabilities and the design of builtenvironments. Areas identified as needing further <strong>at</strong>tention included:1. Developing d<strong>at</strong>abases th<strong>at</strong> contain three-dimensional d<strong>at</strong>a2. Improving our understanding of the functional anthropometry of disability3. Ensuring the collection of reliable, valid and useful d<strong>at</strong>a4. Organizing d<strong>at</strong>a into comprehensive and accessible d<strong>at</strong>abasesIn 2002, the Access Board funded a multi-year project to provide anthropometricin<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion used to help in<strong>for</strong>m decisions about accessibility guidelines andstandards. The Center <strong>for</strong> Inclusive Design and Environmental Access, workingclosely with the Board, developed a preliminary long-range plan to address theseneeds. Phase I of the work involved developing a preliminary work plan. Theworkshop described in this report is Phase II of the work. Subsequent Phases willinvolve focused research and dissemin<strong>at</strong>ion activities.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 15

This report summarizes the activities and recommend<strong>at</strong>ions of a follow-upWorkshop titled “<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong>” th<strong>at</strong> was held inOctober 2003. The Workshop was designed to in<strong>for</strong>m, exchange, and valid<strong>at</strong>eresearch ef<strong>for</strong>ts intended to provide in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about the space requirements inwheeled mobility use. The specific goals of the workshop were to:• Explore the rel<strong>at</strong>ionships between research to codes, standards development,and design• Expand the community of interest further to other stakeholder groups andadditional researchers• In<strong>for</strong>m key stakeholders about the work being done around the world• Review and discuss key issues th<strong>at</strong> will affect a plan of work to address theU.S. Access Board’s needs <strong>for</strong> determining the space requirements of wheeledmobility users• Develop an agenda <strong>for</strong> continuing dialogueThis report is organized in the following way:The in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion g<strong>at</strong>hered from the papers, present<strong>at</strong>ions, and discussions hasbeen organized into the following six topics.1. Guidelines and Standards2. Trends and Issues in Technologies3. Demographics of <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> Users4. Human Modeling of <strong>Mobility</strong> Aid Use5. Anthropometric Research6. Access Board’s Preliminary Research AgendaFor each topic, abstracts of the written papers, key points, and summaries of thediscussions about the present<strong>at</strong>ions are provided. Recommend<strong>at</strong>ions about theBoard’s research agenda and conclusions are collected <strong>at</strong> the end of the report.The list of workshop participants is provided in the Appendix. The interestedreader is encouraged to review the full papers, which are posted on the WorldWide Web:http://www.ap.buffalo.edu/idea/space%20workshop/<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 16

Guidelines and StandardsAnthropometry and accessibility guidelines, Edward Steinfeld,Arch.D.AbstractThis present<strong>at</strong>ion provided an overview of how anthropometry is used in designand policy making, described advantages and limit<strong>at</strong>ions of anthropometricmeasurement methods, and made preliminary recommend<strong>at</strong>ions to improve theuse of anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a to better understand the space requirements ofwheeled mobility users. A brief history of anthropometric research th<strong>at</strong> had aneffect on codes was summarized. Recent advancements in the collection ofanthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a including the use photography, three-dimensional d<strong>at</strong>acollection including whole-body scanning, and kinem<strong>at</strong>ic analysis methods weredescribed. Limit<strong>at</strong>ions th<strong>at</strong> prevent effectively using the in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion in standardsdevelopment were covered. An argument is made to standardize d<strong>at</strong>a collectionacross multiple research sites and projects, including the development ofintern<strong>at</strong>ional standards, in an ef<strong>for</strong>t to improve the overall quality andgeneralizability of anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a so th<strong>at</strong> the space requirements of wheeledmobility devices can be determined.Key Points• Anthropometry allows regul<strong>at</strong>ors to identify the user groups who will beaccommod<strong>at</strong>ed by design and those who will be excluded. Understanding therange of body sizes and abilities of people also can help designers makedecisions about accommod<strong>at</strong>ing the widest range of individuals possible withtheir designs.• Anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a have historically been used to develop reach limits,recommend<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>for</strong> maneuvering clearances, grab bar loc<strong>at</strong>ion, and rampslope.• Anthropometry provides the source d<strong>at</strong>a needed to develop digital humanmodels, and develop reliable simul<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>for</strong> use in testing and evalu<strong>at</strong>ionusing virtual environments.• The anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a typically used by designers is extremely outd<strong>at</strong>ed,with many of the d<strong>at</strong>a sources and tools developed in the 1970s or earlier.Since this time, there have been important changes in the physicalcharacteristics of the popul<strong>at</strong>ion, the demographics of the popul<strong>at</strong>ion and in thetechnologies used by wheeled mobility users.• Newer approaches to d<strong>at</strong>a collection since the 1970s include the use of digitalphotography, 3-D manual digitizing, 3-D scanning, and 3-D motion analysis.Other approaches such as full-scale modeling also involve collectingin<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about user preferences, and system<strong>at</strong>ic observ<strong>at</strong>ions of task<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 17

difficulty <strong>for</strong> tasks per<strong>for</strong>med by individuals in mock-ups of actual builtenvironments.• A number of important anthropometric studies have been recently per<strong>for</strong>med inthe United St<strong>at</strong>es, Australia, United Kingdom and Canada, but these sufferfrom several limit<strong>at</strong>ions. User groups, measurement methods, and researchenvironments vary gre<strong>at</strong>ly from one study to the next, which makes comparingresults or pooling results across studies extremely difficult. Standardizedmethods of anthropometric study are needed <strong>for</strong> standards development.• Anthropometric studies conducted today will need to address the designchallenges of tomorrow and there<strong>for</strong>e trends in the changing demographicsneed to be considered. For example, the use of scooters as a mobility aid isincreasing and these devices generally are longer and have larger turningradiuses than other powered mobility aids.BS 8300 – The research behind the standard, Robert FeeneyAbstractThis paper and present<strong>at</strong>ion provides an overview of the research used in thedevelopment of the British Standard BS 8300: 2001, “Design of buildings and theirapproaches to meet the needs of disabled people – Codes and practice".Research th<strong>at</strong> in<strong>for</strong>med the standard includes basic anthropometry studies,experimental trials and computer aided design analysis.Key Points• The use of system<strong>at</strong>ic analyses of environmental needs <strong>for</strong> people withdisabilities and valid<strong>at</strong>ed research on how those with disabilities useenvironments is still needed.• Studies in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department of Environment,Transport and Region (DETR) involved basic anthropometric research,experimental trialing, field observ<strong>at</strong>ions, and computer aided design analysisspecifically designed to ensure a wide range of disabilities and wheeledmobility technologies were included in the analyses.• Use of multiple approaches focused on physical size, function and preferenceof user groups is needed in the development of design standards.Compliance analysis <strong>for</strong> disabled access, Charles Han, JohnKunz and Kincho LawAbstract<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 18

This paper and present<strong>at</strong>ion described a computer based approach th<strong>at</strong> usesencoding of prescriptive-based provisions and per<strong>for</strong>mance-based methods tosupport compliance and usability analysis <strong>for</strong> accessibility. Prescriptive provisionsinclude the recommended clearances and reach thresholds <strong>for</strong> buildingcomponents given in the ADAAG. Per<strong>for</strong>mance-based simul<strong>at</strong>ions are usedwhere prescriptive provisions appear to be inadequ<strong>at</strong>e. A framework <strong>for</strong> supportof on-line code checking in building design was developed th<strong>at</strong> would allow adesigner to send a design to an autom<strong>at</strong>ed code-checking system. The codecheckingsoftware would gener<strong>at</strong>e an analysis report th<strong>at</strong> can be used by thedesigner to resolve conflicts with the building requirements. The per<strong>for</strong>mancebasedsimul<strong>at</strong>ion approach would test the design <strong>for</strong> usability using a roboticsapproach known as "motion planning". The approach was demonstr<strong>at</strong>ed usingthe accessibility and usability analysis of men and women’s b<strong>at</strong>hrooms.Key Points• Since prescriptive methods of building design do not guarantee usability oraccessibility, use of per<strong>for</strong>mance-based simul<strong>at</strong>ions in combin<strong>at</strong>ion withprescriptive methods may offer additional benefits in design.• An autom<strong>at</strong>ed prescriptive system <strong>for</strong> code-checking can be an extremelyvaluable design tool, but requires the designer to more completely define theobjects in CAD models. The Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Alliance of Interoperability (IAI) hasprovided a framework <strong>for</strong> defining sets of objects called Industry Found<strong>at</strong>ionClasses (IFC’s) th<strong>at</strong> support this object-oriented approach.• Motion planning requires quantit<strong>at</strong>ively determining the p<strong>at</strong>h of use <strong>for</strong> thetarget users, and simul<strong>at</strong>ing the use of the environment along the p<strong>at</strong>h. Thesize and maneuvering characteristics of the wheeled mobility device can bequantit<strong>at</strong>ively modeled to test different user scenarios in the simul<strong>at</strong>ions.Working area of wheelchairs – Details about some dimensionsth<strong>at</strong> are specified in ISO 7176-5, Johann ZieglerAbstractThis paper and present<strong>at</strong>ion summarizes portions of the Intern<strong>at</strong>ionalStandardiz<strong>at</strong>ion Organiz<strong>at</strong>ion’s ISO 7176-5: Wheelchairs – Determin<strong>at</strong>ion ofdimensions and masses th<strong>at</strong> are most relevant to the determin<strong>at</strong>ion of the spacerequirements of wheeled mobility aid users. The purpose of the standard is toprovide technical definitions and procedures <strong>for</strong> measuring dimensions andmasses of wheelchairs and powered scooters. Recommended designs anddesign limits <strong>for</strong> wheeled mobility device dimensions are included.Key Points• ISO standards provide a framework <strong>for</strong> ensuring th<strong>at</strong> consistent language andmeasurement methods are used in d<strong>at</strong>a collection across multiple sites. The<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 19

ISO 7176-5 defines 35 dimensions, including occupied length, occupied width,occupied height, minimum space, turning diameter, turning width, requiredwidth <strong>for</strong> angled corridor, required doorway entry width, required width <strong>for</strong> sideexit and ramp angle.• The recommended design and design limits described in the standards can beused to in<strong>for</strong>m the design of corridors, door widths, and maneuvering spaces.However, more complete anthropometric in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion could be used to improvethe recommend<strong>at</strong>ions made in the standard. The current d<strong>at</strong>a is based on theengineering properties of wheeled mobility devices alone without occupantsand without consider<strong>at</strong>ion of differences in posture or maneuvering ability.Development of Australian Standards and Unmet ResearchNeeds, Murray MountainAbstractThis present<strong>at</strong>ion summarizes the some key aspects of the Australian 1428Standards: "Design <strong>for</strong> Accessibility and <strong>Mobility</strong>”. While a total of 10 parts arecurrently planned, 4 parts have been completed. These cover: 1. generalrequirements <strong>for</strong> building access, 2. enhancements to the built environment, 3.design requirements <strong>for</strong> children with disabilities, and 4. design <strong>for</strong> people withvisual impairments. The anthropometric research used in the development ofeach of the standards is described.Key Points• Anthropometric research conducted in the 1980s and 1990s was used in thedevelopment of the Australian 1428 Standards. AS1428.1 – 1991 – Generalrequirements <strong>for</strong> access – New building work was based on research by JohnBails in the mid 1980’s using approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 500 subjects between the ages of18 to 60 years, which included wheelchair users, people with ambulantdisabilities and those who were blind or had a vision impairment. AS1428.2 –1992 - Enhanced and additional requirements – Buildings and facilities wasalso developed from Bails' research and gives d<strong>at</strong>a on how to enhance thebuilt environment. AS1428.3 – 1992 - <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> children andadolescents with physical disabilities, was based on research in the early 90’sby Barry Seeger including manual and electric wheelchair users, and childrenwith ambulant disabilities. AS1428.4 – 2002 – Tactile Indic<strong>at</strong>ors covers designissues particularly relevant <strong>for</strong> with people who are blind who have visualimpairments.• The design issues covered include door design and clearances includingclearances in vestibules, the dimensions of landings and ramps, and somecontrol loc<strong>at</strong>ions based on reach ranges.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 20

Anthropometric Research in Australia, Rod HunterAbstractThis present<strong>at</strong>ion provides a brief overview of recent anthropometric researchper<strong>for</strong>med in Australia to help in<strong>for</strong>m building standards. Key parameters inmaneuvering were described and implic<strong>at</strong>ions on policy decisions in Australiawere summarized.Key Points• Key parameters th<strong>at</strong> affect the maneuvering abilities of wheeled mobilitydevice users include the overall length and width of the wheelchair, turningradius, and axle design.• The shape of the front portion of the wheeled mobility aid and orient<strong>at</strong>ion of theuser on the chair will have a dram<strong>at</strong>ic effect on the space needed <strong>for</strong>approaches.• Use of percentiles in univari<strong>at</strong>e analyses of even the key parameters do notprovide a good estim<strong>at</strong>e of the percent of individuals capable of successfullymaneuvering in a space, and there<strong>for</strong>e such analyses should not be heavilyweighted in standards development.• Standards cannot be based on a standardized wheelchair design since thereare so many different designs available and the design affects functionalcapabilities.Disability Discrimin<strong>at</strong>ion Act 1995 (UK), Donald MacDonaldAbstractThis present<strong>at</strong>ion provides a brief overview of key aspects of the UnitedKingdom’s 1995 Disability Discrimin<strong>at</strong>ion Act th<strong>at</strong> are particularly relevant towheeled mobility space requirements in transport<strong>at</strong>ion systems. Part 3 coverstransport<strong>at</strong>ion infrastructure <strong>at</strong> bus st<strong>at</strong>ions and bus stops, and Part 5 coversaccessibility regul<strong>at</strong>ions rel<strong>at</strong>ed to buses, coaches, trains and taxis.Key Points• The 1995 Disability Discrimin<strong>at</strong>ion Act provides accessibility standards <strong>for</strong>transport<strong>at</strong>ion systems in the United Kingdom. Standards were phases in <strong>for</strong>different vehicle types (e.g., single deck buses, double deck buses, coaches,taxis, etc.).• On buses, protected space with a backrest is used instead of tie downs toenhance safety of wheeled mobility device users during travel. Coaches dohave securement systems.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 21

• More in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about the <strong>Mobility</strong> Inclusion Unit of the Department <strong>for</strong>Transport is on the web: http://www.mobility-unit.dft.gov.uk/. In<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion aboutthe Disabled Persons Transport Advisory Committee can be found <strong>at</strong>http://www.dptac.gov.uk/Challenges with the ADAAG, Marsha MazzKey PointsThis present<strong>at</strong>ion provides a brief overview of key fe<strong>at</strong>ures and design challengesof the ADAAG.• The ADAAG provides minimum design requirements and is not a buildingcode. There<strong>for</strong>e, designers should <strong>at</strong>tempt to develop environments th<strong>at</strong>surpass r<strong>at</strong>her than simply meet the requirements of ADAAG.• Revisions to the ADAAG are being challenged because of a lack of neededd<strong>at</strong>a. Key issues include lowering the controls on vending machines, designissues to allow wheeled mobility users to use <strong>for</strong>ward approaches whenaccessing w<strong>at</strong>er fountains, space requirements <strong>for</strong> transfers in showerfacilities, handrail shapes, clearances and orient<strong>at</strong>ions, and the design of theappropri<strong>at</strong>e sight lines in assembly areas.General Discussion of Guidelines and StandardsAnother approach to development of guidelines involves the dissemin<strong>at</strong>ion of“Best Practices”. For example, Dave Rapson developed such a guide th<strong>at</strong>included recommend<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>for</strong> the design of environments to accommod<strong>at</strong>epowered scooters th<strong>at</strong> was developed by the Province of Manitoba and City ofWinnipeg.Although simul<strong>at</strong>ion tools are very welcome <strong>for</strong> use in comparison of standardsand help bring the results to the designer and user, their use in the developmentof standards is not yet clear. Use of such tools will require new ways to interpretthe d<strong>at</strong>a and the d<strong>at</strong>a interpret<strong>at</strong>ion is an important element of the standardsdevelopment process.The costs and benefits of guidelines and standards <strong>for</strong> space requirements arenot considered in a rigorous way across countries.The need <strong>for</strong> standardizing research methods and the way th<strong>at</strong> in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion isapplied to design was emphasized.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 22

Trends and Issues in TechnologiesTrends and issues in wheeled mobility technologies, RoryCooper, Ph.D., and Rosemarie Cooper, M.P.T., A.T.P.AbstractThis commissioned paper and present<strong>at</strong>ion summarized the st<strong>at</strong>e of currenttechnologies, trends and market indic<strong>at</strong>ors of wheeled mobility devices, and theirpotential impacts on the design of the built environment and transport<strong>at</strong>ionsystems. Manual wheelchairs can be c<strong>at</strong>egorized as depot, light weight, ultra-lightweight, bari<strong>at</strong>ric, standing and specialized. The depot manual chair is the mostcommon manual chair due to its low cost and high durability. Powered mobilityaids include lightweight devices <strong>for</strong> indoor use, those used <strong>for</strong> indoor and lightoutdoor use, those used <strong>for</strong> active indoor and outdoor user, powered scooters,bari<strong>at</strong>ric, standing, push rim power activ<strong>at</strong>ed (PAPAW) and specialized se<strong>at</strong>ingdevices. The market <strong>for</strong> both manual and powered bari<strong>at</strong>ric chairs is expected togrow the most rapidly of all mobility device c<strong>at</strong>egories due to the increasingprevalence of obesity in the U.S. Bari<strong>at</strong>ric chairs are generally much wider thanother types of chairs. Thus, users of this type of chair can encounter uniquebarriers in the environment. Markets <strong>for</strong> other types of chairs are also expected togrow, although not as rapidly as the bari<strong>at</strong>ric chair market. The various trends willmost likely lead to an overall increase in chair size and in space requirements.There are technological limit<strong>at</strong>ions associ<strong>at</strong>ed with the design of wheeled mobilitydevices th<strong>at</strong> require additional research and design work. Further researchshould focus on reducing risks to secondary conditions associ<strong>at</strong>ed with wheeledmobility device use, determining utiliz<strong>at</strong>ion r<strong>at</strong>es of wheelchairs in differentsettings, and new mobility aid technologies to accommod<strong>at</strong>e a gre<strong>at</strong>er range ofindividuals who need assistance such as the elderly, the obese and those withmultiple sclerosis. Research focused on improving safety during a wide range offunctional activities is also needed.Key Points• Current manual chairs range in quality, com<strong>for</strong>t, per<strong>for</strong>mance, durability andcost. Although the Center <strong>for</strong> Medicare and Medicaid Services is among thetop purchasers of wheelchairs in the U.S., its selection of wheelchairs is basedon durability, use in the home and cost, r<strong>at</strong>her than the full range of needs ofwheeled mobility aid users. There<strong>for</strong>e, it is not surprising th<strong>at</strong> depot chairs areby far the most common chair.• Only 20-25% of people worldwide who use wheeled mobility devices reportth<strong>at</strong> there mobility needs are met.• There is a high degree of variability in the turning radius and stability ofpowered wheelchairs. Those with rear-wheel drive typically have a largerturning radius, those with mid-wheel drive have a shorter turning radius but are<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 23

more susceptible to tipping, and those with front-wheel drive off both a tightturning radius and stability, although are more difficult to control during straighttravel.• There is a gre<strong>at</strong> variety in power wheelchair configur<strong>at</strong>ions since the se<strong>at</strong>ingsystems of one manufacturer can be used with the frames of anothermanufacturer to customize the chair to the needs of the user.• Because pressures sores and pain are problems associ<strong>at</strong>ed with conventionalchair designs, chairs th<strong>at</strong> provide gre<strong>at</strong>er postural adjustability may bebeneficial to users but these chairs increase the variability of spacerequirements <strong>for</strong> different tasks.• Scooters and powered wheelchairs are going to become increasing similar asef<strong>for</strong>ts are made to make powered wheelchairs more transportable andmodular.• Even the most advanced wheeled mobility systems have important limit<strong>at</strong>ionswith respect to their use in the built environment. For example, theIndependence 3000 IBOT Transporter uses a variety of electronic sensors toadjust maneuverability, stability and function to the terrain, but currently has ase<strong>at</strong> surface too high to be used easily <strong>at</strong> work surfaces <strong>at</strong> conventionalheights.• Given th<strong>at</strong> the number of individuals in nursing homes is expected to double inthe next 30 years, the use of wheeled mobility technologies th<strong>at</strong> improvefunction of older people in these environments is an important priority.• Market trends suggest th<strong>at</strong> the space requirements <strong>for</strong> wheeled mobility willincrease. For example, the market <strong>for</strong> both manual and powered bari<strong>at</strong>ricchairs is expected to grow the most rapidly of all chair c<strong>at</strong>egories, and markets<strong>for</strong> “PAPAW” chairs and specialized se<strong>at</strong>ing in chairs, although now small, isexpected to also grow rapidly.• Labor<strong>at</strong>ory-based d<strong>at</strong>a collection on function as per<strong>for</strong>med in conventionalanthropometric studies may not reflect function in actual commercial, public orresidential environments. There<strong>for</strong>e, other types of studies designed toevalu<strong>at</strong>e the space requirements of wheeled mobility devices are needed.• Further research should focus on reducing risks to secondary conditionsassoci<strong>at</strong>ed with wheeled mobility device use, determining utiliz<strong>at</strong>ion r<strong>at</strong>es ofwheelchairs in different settings, and new mobility aid technologies toaccommod<strong>at</strong>e a gre<strong>at</strong>er range of individuals who need assistance such as theelderly, people who are obese and those who have multiple sclerosis.Research focused on improving safety during a wide range of functionalactivities is also needed.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 24

DiscussionDiscussions focused on the role of technology in affecting wheeled mobility deviceuse trends in the United St<strong>at</strong>es and elsewhere, and how this could affectenvironmental design policies.For example, it was reported th<strong>at</strong> powered scooter use will soon exceed powerwheelchair use in the United Kingdom and a similar trend is predicted <strong>for</strong> theUnited St<strong>at</strong>es. Scooters were originally designed <strong>for</strong> outdoor environments, butthey are being increasingly used indoors. Wh<strong>at</strong> impact will scooters have on thedesign of environments in the future? Will the industry adapt designs to reflectincrease use of scooters indoors?Because environments do not accommod<strong>at</strong>e all devices with uni<strong>for</strong>m accessibility,individuals who use wheeled mobility aids adapt by, <strong>for</strong> example, owning morethan one device. On average, wheeled mobility users have two devices and 50%of wheeled mobility users also use a walker.Trends and issues in pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m lifts, David BalmerAbstractThis commissioned paper and present<strong>at</strong>ion summarized the current st<strong>at</strong>e oftechnology in pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m lift design and standards. While elev<strong>at</strong>ors are currently themost effective vertical transport<strong>at</strong>ion system in terms of speed, capacity, rise andsafety, they have some major drawbacks <strong>for</strong> accessibility - cost and spacerequired, particularly <strong>for</strong> short-range vertical changes. Pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m lifts and stairwaychairlifts are the “device of choice” <strong>for</strong> small elev<strong>at</strong>ion changes in existingbuildings, but, their use is limited by the Americans with Disabilities ActAccessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) to very specific circumstances in new buildings.Pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m lifts are ADA compliant, but chairlifts are not since they do not provideaccess <strong>for</strong> a wheeled mobility device. The A18 Standard of the American Societyof Mechanical Engineers (ASME), under the sponsorship of the AccessibilityEquipment Manufacturers Associ<strong>at</strong>ion (AEMA) was published in January 2000with key input from the U.S. Access Board. It has had a very important impact onthe requirements <strong>for</strong> lift equipment and other rel<strong>at</strong>ed standards. This standardelimin<strong>at</strong>ed the use of keys th<strong>at</strong> restrict access to lifts, allows the use of inclinedvertical lifts th<strong>at</strong> can be more effectively incorpor<strong>at</strong>ed into existing stairways withlittle impact on other stairway traffic, promoted new developments in the design ofvertical lifts, increased the allowable vertical travel of a lift, and strengthened thelift approach ramps to improve safety and accessibility. But, there are stillimportant design problems rel<strong>at</strong>ed to lifts th<strong>at</strong> need to be addressed. Theincreases in size and weights of powered mobility devices may require somechanges to the standard. This could include, <strong>for</strong> example, increasing the currentlyrequired 1.67 m 2 of floor space to 2 m 2 , and increasing the minimum weightcapacities of lifts. Allowing the use of lifts in new construction, as has beensuggested <strong>for</strong> the new ADA requirements, would be extremely problem<strong>at</strong>ic. This<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 25

would elimin<strong>at</strong>e or reduce accessibility in buildings or building additions th<strong>at</strong> arenot required to have elev<strong>at</strong>ors. Finally, ASME is <strong>at</strong>tempting to simplify the codechanging process so th<strong>at</strong> innov<strong>at</strong>ive vertical lift solutions can more quickly bebrought to market.Key Points• Vertical lift technologies are important to the accessibility of existing and newcommercial and public buildings.• The U.S. Access Board has played an important role in ensuring th<strong>at</strong> theAMSE A18 standard appropri<strong>at</strong>ely addresses the needs of those who requirelifts.• The increasing size and weights associ<strong>at</strong>ed with newer powered mobilitydevices need to be addressed in future revisions of the design standards.• NAFTA drove harmoniz<strong>at</strong>ion between Canada and the United St<strong>at</strong>es in termsof the standards <strong>for</strong> lift design, and, it is an example of the emergingglobaliz<strong>at</strong>ion in standards development <strong>for</strong> assistive technologies.DiscussionThere appears to be a need <strong>for</strong> more communic<strong>at</strong>ion between researchers andstandards developers, so th<strong>at</strong> standards can better address the needs of theusers. Since many standards are quite restrictive, one fear is th<strong>at</strong> standards suchas those rel<strong>at</strong>ed to lift design would limit innov<strong>at</strong>ion.While use of pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m lifts has vastly improved the accessibility to builtenvironments, use of these devices can still be difficult and time consuming.Ef<strong>for</strong>ts need to be devoted to universal design altern<strong>at</strong>ives th<strong>at</strong> elimin<strong>at</strong>e the need<strong>for</strong> lifts in built environments.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 26

Demographics of <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> UsersTrends and issues in disability d<strong>at</strong>a and demographics, MitchellLa Plante, Ph.D.AbstractThis commissioned paper and present<strong>at</strong>ion summarizes the current demographicst<strong>at</strong>us and trends of mobility aid users in terms th<strong>at</strong> can be used by policy makersto identifying current and/or future needs of this user group. The trends and recentst<strong>at</strong>us among mobility aid users in health and functional limit<strong>at</strong>ion, perceiveddisability, financial resources, unmet device needs, and unmet environmentalneeds are summarized from n<strong>at</strong>ional surveys conducted repe<strong>at</strong>edly in recentyears. These surveys include the U.S. N<strong>at</strong>ional Health Interview Survey and theU.S. Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Particip<strong>at</strong>ion. The numberof wheeled mobility users has more than quadrupled in the last 30 years toapproxim<strong>at</strong>ely 2 million users. This number may exceed 4 million users by 2010.Growth in the number of users is likely due to changing social and technologicaltrends, r<strong>at</strong>her than an increase in the prevalence of disability or the increasednumbers of elderly people. The effects of the growth in the older popul<strong>at</strong>ion on theuse of wheeled mobility devices is uncertain due, in part, to limit<strong>at</strong>ions in thecurrent n<strong>at</strong>ional survey methods. There are higher overall proportions of womenwho use wheeled mobility devices, although the number of male users exceedsthe number of female users among young adults. The most frequently reportedneeds rel<strong>at</strong>ed to building design are improved doors and elev<strong>at</strong>ors, lifts and stairglides. Finally, improvements to n<strong>at</strong>ional surveys th<strong>at</strong> include questions onwheeled mobility devices are needed to improve the quality and detail of thein<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion available rel<strong>at</strong>ed to the frequency and severity of impairments and theutiliz<strong>at</strong>ion of assistive technologies. The research community and sponsors arestrongly encouraged to ensure th<strong>at</strong> obtaining more thorough and more accur<strong>at</strong>ein<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about those with mobility impairments is a priority <strong>for</strong> future surveyef<strong>for</strong>ts.Key Points• There are approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 2 million users of wheeled mobility users, and, trendssuggest th<strong>at</strong> this number may exceed 4 million users by 2010. Approxim<strong>at</strong>ely17% of the wheeled mobility device users use powered wheelchairs orscooters.• Growth in the number of users is likely due to society and technological trendssuch as improvements in the design of mobility aids, improved accessibility todevices, and social acceptance of device use, r<strong>at</strong>her than an increasedprevalence of disability or the number of elderly people in the popul<strong>at</strong>ion.• The effects of the growing aging popul<strong>at</strong>ion on the use of wheeled mobilitydevices is uncertain due, in part, to the limit<strong>at</strong>ions in the current n<strong>at</strong>ional<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 27

survey methods. However, those 65 and over make up 56% of the users ofwheeled mobility aids, and are more likely to use manual versus poweredmobility devices.• The rel<strong>at</strong>ionship between the proportion of those having difficulty walkingwithout assistance and the proportion of people who used wheeled mobilityaids changes with age. This may be due, in part, to changing expect<strong>at</strong>ions ofmobility. For example, there is a disproportion<strong>at</strong>e number of elderly peoplewho are more likely to use canes and walkers r<strong>at</strong>her than wheeled altern<strong>at</strong>ivesbut have fairly low mobility requirements, as compared to younger adults whoare more likely to select wheeled devices to improve mobility over longdistances.• There are higher overall proportions of women who use wheeled mobilitydevices, particularly among older popul<strong>at</strong>ion. However, the number of maleusers exceeds the number of women users among younger adults.• The p<strong>at</strong>terns of mobility aid use are similar across different c<strong>at</strong>egories ofethnicity.• The device and environmental needs of wheeled mobility users in health carefacilities will need careful consider<strong>at</strong>ion in the future. When compared to nonwheeledmobility aid users, people who use wheeled mobility devices aremuch more likely to report poor health (40% compared to 2%), a gre<strong>at</strong>erfrequency of hospitaliz<strong>at</strong>ion and more frequent use of health care services.The most frequently reported building needs are usable doors and elev<strong>at</strong>ors,lifts and stair glides.• Just over one quarter of wheeled mobility device users drive a vehicle, whichoften requires special assistive equipment. A large majority of wheeledmobility aid users report difficulty gaining access to public transport<strong>at</strong>ion andvery few actually use it.• Revisions to n<strong>at</strong>ional surveys are needed to improve the quality and detail ofthe in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion rel<strong>at</strong>ed to the frequency and severity of impairments and theutiliz<strong>at</strong>ion of assistive technologies. For example, the last NHIS-D survey didnot distinguish between powered or manual wheeled mobility device users.Additionally, n<strong>at</strong>ional surveys do not inquire about why a particular device wasselected and wh<strong>at</strong> altern<strong>at</strong>ives were considered.• The research community and sponsors are strongly encouraged to ensure th<strong>at</strong>obtaining in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about mobility impairments remains a priority and isimproved in future survey ef<strong>for</strong>ts. Proposed questions, <strong>for</strong> example, could bepilot tested and valid<strong>at</strong>ed among groups of wheeled mobility aid users andthen submitted <strong>for</strong> inclusion in the n<strong>at</strong>ional survey ef<strong>for</strong>ts.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 28

DiscussionThe discussions focused on the need to better understand the demographicvariables associ<strong>at</strong>ed with choice of mobility type and limit<strong>at</strong>ions in the n<strong>at</strong>ionald<strong>at</strong>a g<strong>at</strong>hering process.There are many different types of mobility devices. There are many reasons whyan individual selects a particular device type. Surveys need to inquire about thereasons <strong>for</strong> specific choices in order to in<strong>for</strong>m purchasing policies, designpractices and standards.Currently, the N<strong>at</strong>ional Health Interview Survey combines different accessibilityproblems into one question, “Do you have problems with accessibility?” Suchquestions provide very limited useful in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion and may encourage a responsebias th<strong>at</strong> results in an underestim<strong>at</strong>ion of the prevalence of wheeled mobilitydevice use. Improvements to this survey are needed.A registry of wheeled mobility users could be developed from the surveyrespondents, provided th<strong>at</strong> the appropri<strong>at</strong>e consent could be obtained. Such aregistry could provide a valuable resource <strong>for</strong> future surveys designed to capturedetailed in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about barriers in design and factors th<strong>at</strong> affect the selection ofwheeled mobility devices.More in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about the use and selection of wheeled mobility devices ininstitutions is also needed.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 29

Human Modeling of <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> Aid UseWheelchair simul<strong>at</strong>ion in virtual reality, Michael Grant, Ph.D.AbstractThis paper and present<strong>at</strong>ion summarized the results of a project <strong>at</strong> the <strong>University</strong>of Str<strong>at</strong>hclyde involving the development of a wheelchair motion pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m which, inconjunction with a virtual reality (VR) facility, can be used to address issues ofaccessibility in the built environment. The development of the approach is acollabor<strong>at</strong>ive ef<strong>for</strong>t between architects, bioengineers and user groups and hasinvestig<strong>at</strong>ed topics rel<strong>at</strong>ed to pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m design and construction, interfacing, testingand user evalu<strong>at</strong>ion. Current research is directed towards developing thisprototype, extending existing simul<strong>at</strong>ion capabilities and exploring its utility in adesign environment. The outcome of the project has been the development of ahaptic interface th<strong>at</strong> allows manual and powered wheelchair users to navig<strong>at</strong>ewithin VR simul<strong>at</strong>ions of buildings through the use of their own wheelchair andprovides the user with feedback rel<strong>at</strong>ed to the sense of ef<strong>for</strong>t required to propelthe wheelchair. User testing has demonstr<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> the system provides a realisticdepiction of wheelchair use in different environments.Key Points• The use of a wheelchair motion pl<strong>at</strong><strong>for</strong>m used in conjunction with virtual realitycan be a useful design and educ<strong>at</strong>ion tool th<strong>at</strong> allows manual and poweredwheelchair users to navig<strong>at</strong>e safely within VR simul<strong>at</strong>ions of prototypebuildings using their own wheelchairs. Collisions with virtual objects combinevisual and non-visual stimul<strong>at</strong>ion in a manner th<strong>at</strong> is analogous to real world.• Future research should be directed <strong>at</strong> extending the capabilities of such asystem by increasing the ability of the wheeled mobility device user to interactwith the virtual world.Virtual reality and full scale modeling – a large mixed realitysystem <strong>for</strong> particip<strong>at</strong>ory design, Roy Davies, Elisabeth Delhom,Birgitta Mitchell, Paule T<strong>at</strong>eAbstractThis paper and present<strong>at</strong>ion summarized a general approach to simul<strong>at</strong>ion knownas “The Envision Workshop.” This approach integr<strong>at</strong>es tools th<strong>at</strong> encourageparticip<strong>at</strong>ory technical support in the design process. It utilizes full scale modelingof the environment and an optical tracking system th<strong>at</strong> feeds in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion onposition and movement of people and objects into a virtual reality model <strong>for</strong> realtimeanalysis of virtual designs. While the methods appear to provide unique andpotentially valuable design in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion, challenges rel<strong>at</strong>ed to the limit<strong>at</strong>ions of thetracking system, how to track environmental fe<strong>at</strong>ures and integr<strong>at</strong>ing the tools<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 30

effectively still remain. The system has gre<strong>at</strong> potential <strong>for</strong> combining functionalanthropometry of wheeled mobility use with qualit<strong>at</strong>ive studies th<strong>at</strong> exploreperceptions and <strong>at</strong>titudes toward design fe<strong>at</strong>ures.Key Points• Full scale modeling techniques allow designers and researchers to capitalizeon the user’s experience. They can be used to identify the most importantdesign challenges and rapidly develop effective solutions to overcome them.• These tools th<strong>at</strong> can be used collectively to facilit<strong>at</strong>e an effective particip<strong>at</strong>orydesign process including the use of brainstorming and improvis<strong>at</strong>ional drama.• Virtual reality and full-scale modeling can be integr<strong>at</strong>ed effectively in researchand design. Motion tracking systems can be used to collect kinem<strong>at</strong>icin<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong> is then used in virtual reality software <strong>for</strong> real-time virtualevalu<strong>at</strong>ions of the full-scale models. Fe<strong>at</strong>ures of the environment can bemanipul<strong>at</strong>ed post-hoc after d<strong>at</strong>a collection to evalu<strong>at</strong>e altern<strong>at</strong>ive designscenarios.• Challenges in developing the system further are rel<strong>at</strong>ed to the limit<strong>at</strong>ions of thetracking system, how to track environmental fe<strong>at</strong>ures th<strong>at</strong> change during thetask simul<strong>at</strong>ions, and integr<strong>at</strong>ing the tools effectively.HADRIAN Human Modeling Design Tool, Mark Porter, Ph.D.AbstractThis present<strong>at</strong>ion provided an overview of how anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a and tasksimul<strong>at</strong>ion were used in the development of the SAMMIE and HADRIAN softwarepackages, and how these two software tools can be used effectively in design.The packages combine video, anim<strong>at</strong>ions and structural dimensions in ways th<strong>at</strong>improve the use of anthropometry in the design process. Link lengths, range ofmotion, posture prediction algorithms and functional task in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion provide keyin<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion to the digital human models used in the software. The designer can“build a task” in a virtual environment and the interface can be used to estim<strong>at</strong>ethe number of virtual users who would “fail” the task based on fit between theirabilities and sizes and the characteristics of the design. An example of anautom<strong>at</strong>ic teller machine was used to illustr<strong>at</strong>e the benefits of the approach. Oneof the most important limit<strong>at</strong>ions of the current software is of the rel<strong>at</strong>ively smallset of user groups and tasks th<strong>at</strong> have been incorpor<strong>at</strong>ed. More research isneeded to expand the software package capabilities by adding tasks and virtualuser groups th<strong>at</strong> can be incorpor<strong>at</strong>ed in evalu<strong>at</strong>ions.Key Points• SAMMIE and HADRIAN are powerful design tools in which a design isevalu<strong>at</strong>ed against the body sizes and capabilities of “whole” virtual individualsr<strong>at</strong>her than individual dimensions.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 31

• Potential benefits include the possibility of making ergonomic evalu<strong>at</strong>ions ofthe person-environmental fit using virtual techniques during the designprocess. This can improve communic<strong>at</strong>ion between designers, consumers andpolicy makers.• The HADRIAN software package currently includes link lengths, range ofmotion, posture prediction algorithms and functional task in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion of 40individuals without disabilities, 40 ambulant individuals with a disability, and 20users of wheeled mobility devices.• Based on the structural and functional anthropometric d<strong>at</strong>a, designers can testvirtual tasks in virtual environments to determine the percentage of individualswho have the ability to complete a task in the specific context of theenvironment and also people with specific characteristics, e.g. an older frailperson with left side paralysis due to stroke. Reasons why a design cannot beused by a user group or individual become clearly obvious in the virtual tasksimul<strong>at</strong>ions.• Perhaps the largest limit<strong>at</strong>ion of the approach is the limited amount of d<strong>at</strong>a th<strong>at</strong>is currently available <strong>for</strong> testing. Additional individuals and tasks are needed<strong>for</strong> the design tool to provide a more accur<strong>at</strong>e understanding of how a designwill affect usability. The software is designed to accept new activities and newpeople with little difficulty.Mannequin Pro Human Modeling Design Tool, Dan HeltAbstractThis present<strong>at</strong>ion provided an overview of the Mannequin Pro ergonomic designtool. Early versions of a digital wheeled mobility user model were described. Thesoftware allows the user to examine the fit between a fairly simple st<strong>at</strong>ic virtualmodel of a user and the environment to be evalu<strong>at</strong>ed. The current version of thesoftware also allows simple three-dimensional biomechanical analysis.Key Points• Currently the Mannequin Pro software assumes th<strong>at</strong> the structural dimensionsof an ambulant adult are similar to the wheeled mobility user. Negoti<strong>at</strong>ions areunderway with the Center <strong>for</strong> Inclusive Design and Environmental Access toobtain structural d<strong>at</strong>a of wheeled mobility users th<strong>at</strong> would introduce moreaccur<strong>at</strong>e digital "Mannequin" models of this user group.General Discussion of Human Modeling Applic<strong>at</strong>ions toDetermine <strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong>While digital human models provide in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong> cannot be collected withconventional anthropometric methods, it is not clear to the standards developers ifuse of such tools will be of gre<strong>at</strong> value. Typically, the questions th<strong>at</strong> designers<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 32

and code officials need answered do not require the level of detail provided bydigital human models and simul<strong>at</strong>ions, and, development and purchase of digitalhuman models is costly. Further discussion is needed to explore how digitalhuman modeling and simul<strong>at</strong>ion methods can be used effectively in codedevelopment.For both design and code development, digital human models must be valid<strong>at</strong>ed.Usually only components of the models (e.g., posture prediction <strong>for</strong> specific tasks)are evalu<strong>at</strong>ed, and there is not very much in<strong>for</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ion about the errors associ<strong>at</strong>edwith using digital human models in design.<strong>Space</strong> <strong>Requirements</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Wheeled</strong> <strong>Mobility</strong> 33