ATN July-August 2001 - Appalachian Trail Conservancy

ATN July-August 2001 - Appalachian Trail Conservancy

ATN July-August 2001 - Appalachian Trail Conservancy

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

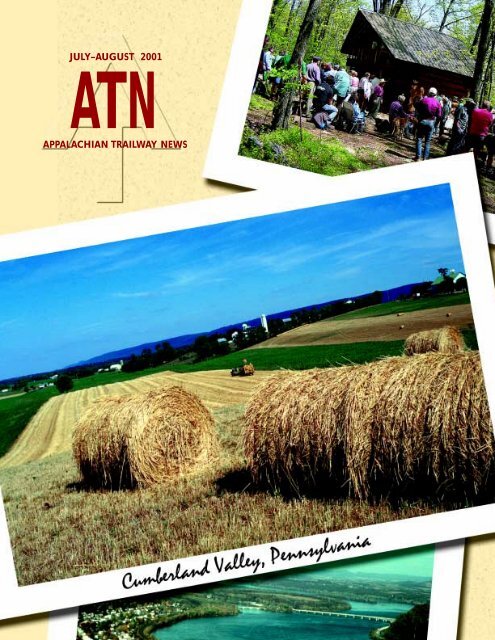

JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong><strong>ATN</strong>APPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS

2 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

APPALACHIAN TRAILJULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong><strong>ATN</strong>APPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWSMAINETOGEORGIAON THE COVERScenes from near Shippensburg—(top tobottom) Ed Garvey Shelter in Maryland(photo: Robert Rubin); fields near BoilingSprings, Pennsylvania (photo: ThomasScully); Susquehanna River near Duncannon,Pennsylvania (photo: V. Collins Chew).Inside: Saddleback Mountain <strong>Trail</strong>, SandyRiver Plantation, Maine (photo: J. AndrewWalsh).VIEWPOINTSSHELTER REGISTER ♦ LETTERS 4FROM THE CHAIR ♦ DAVID B. FIELD 5REFLECTIONS: HARD WEATHER 24MINISTRY OF FUNNY WALKS ♦ FELIX J.MCGILICUDDY 31WHITE BLAZESPAPER TRAIL ♦ NEWS FROM HARPERS FERRY 7SIDEHILL ♦ NEWS FROM CLUBS ANDGOVERNMENT AGENCIES 12TREELINE ♦ NEWS FROM ALONG THEAPPALACHIAN TRAIL 16BLUE BLAZESSHARING THE TRAIL ♦ HUMANS AREN’T THEONLY ONES WHO FOLLOW THE APPALACHIANTRAIL ♦ CHRISTINE WOODSIDE 18HIKER BREAD FOR BEGINNERS♦ FRED FIRMAN 21TREADWAYMEMORIAL GIFTS 27TRAIL GIVING 28NOTABLE GIFTS 29PUBLIC NOTICES 30APPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 3

<strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>wayNewsVOLUME 62, NUMBER 3 • JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong><strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>way News is published by the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> Conference, a nonprofit educational organization representingthe citizen interest in the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> and dedicatedto the preservation, maintenance, and enjoyment of the<strong>Appalachian</strong> trailway. Since 1925, the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conferenceand its member clubs have conceived, built, and maintainedthe <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> in cooperation with federal andstate agencies. The Conference also publishes guidebooks andother educational literature about the <strong>Trail</strong>, the trailway, and itsfacilities. Annual individual membership in the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> Conference is $30; life membership, $600; corporate membership,$500 minimum annual contribution.Volunteer and freelance contributions are welcome. Please includea stamped, self-addressed envelope with your submission.Observations, conclusions, opinions, and product endorsementsexpressed in <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>way News are those of the authorsand do not necessarily reflect those of members of theBoard or staff of the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conference.DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC AFFAIRSBrian B. KingEDITORRobert A. RubinBOARD OF MANAGERSChairDavid B. FieldVice ChairsBrian T. Fitzgerald Thyra C. SperryJames HutchingsTreasurerKennard R. HonickSecretaryMarianne J. SkeenAssistant SecretaryArthur P. FoleyNew England RegionStephen L. Crowe Carl DemrowJohn M. Morgan Andrew L. PetersonAnn H. Sherwood Steven SmithMid-Atlantic RegionWalter E. Daniels Charles A. GrafSandra Marra Eric C. OlsonGlenn Scherer William SteinmetzSouthern RegionBob Almand Theresa A. DuffeyMichael C. McCormackWilliam S. Rogers Vaughn H. ThomasJames M. Whitney, Jr.Members at LargeAl Sochard Dawson WinchEXECUTIVE DIRECTORDavid N. StartzellWorld Wide Web: www.appalachiantrail.org<strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>way News (ISSN 0003-6641) is published bimonthly,except for January/February, for $15 a year by the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>Conference, 799 Washington Street, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425, (304)535-6331. Bulk-rate postage paid at Harpers Ferry, WV, and other offices.Postmaster: Send change-of-address Form 3597 to <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong>way News, P.O. Box 807, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425.Copyright © <strong>2001</strong>, The <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conference. All rightsreserved.SHELTER REGISTERBlistersLetters from our readersThe article of March/April <strong>2001</strong>, “Aye,There’s the Rub,” by Dr. Paul Gill, andthe May/June <strong>2001</strong> Shelter Registerletter, “Blisters,” by Brian Booth, bothhave their merits but do need a commentor two.The only good blister is the one youfailed to get or left back home. Once Ilearned the secret of blister preventiontwenty-five years ago, I have never hadanother.The cause of a blister, usually on theheel, is no mystery—it comes from friction.No friction, no blister. It is frictionthat causes a blister on your noncallusedhands in the spring when you first use ashovel or hoe. Friction will rub a blisteron your palm or the surface of a finger inno time. A good work glove will spareyour palm or finger by having the frictionoccur between your glove and the toolhandle and not between your skin and thetool handle. The mechanism is the samefor the heel blister; only the location andthe tool are different.As you walk, friction is generated bythe back of the boot, the tool, makingyour sock slide up and down on your heel.The friction on the heel causes the moresuperficial layers of the skin to separatefrom the deeper layers; now there is a potentialspace between the two separatedlayers. The sterile inflammation causedby the friction results in the formation ofblister fluid or serum between the twoseparated layers. This creates what we allrecognize as a depressing blister that mayruin our trip. Remove the friction, andthere is no blister.The start of any heel-blister preventionprogram is the acquisition of a pair ofmodern, well-fitting, well-broken-inboots—those with a softer, more cushionedlining, rather than a pair of stiffleather boots with no lining. The nextthing is to wear a pair of tight-fitting hosemade of a synthetic material. Over thesesocks wear your thicker, cushier socks.Now, any friction that occurs is betweenthe two pairs of socks, not between thelayers of your skin. As a further prevention,you can use moleskin in blisterproneareas before a blister forms. Finally,using a drying foot powder between thetwo pairs of socks will help them slideover each other in an easier fashion, eliminatingthe friction on your heel.Heed what I say, and say good-bye toblisters!A. Ted Hill, Jr., M. D.Asheville, N.C.♦Blister articles over many decades haveomitted something important. Everyoneagrees blisters are uncomfortable andcan lead to really serious conditions if notappropriately cared for. Properly fittingand broken-in boots are always the firstand essential requirement. Hot spots thatpreview blisters receive their share ofcommentary. And, articles such as theone in the March–April issue discusswhat to do with blisters after they havereached maturity—the discussion ofwhich elicited a letter in the May–Juneissue. The latter actually touches on bootcomfort, both “tightness” and “looseness”(two pairs of socks are usually recommended).But, nowhere does anyonewrite about sock thickness and howthickness relates to how the foot can (andalmost always does—read “must”) changeas the day passes and the weeks roll by.Feet get hot and frequently swell withthe passing hours, so hikers are advisedLetters<strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>way Newswelcomes your comments. Lettersmay be edited for clarity and length.Please send them to:Letters to the Editor<strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>way NewsP.O. Box 807Harpers Ferry, WV 25425-0807E-mail: 4 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

From the ChairDavid B. Fieldto change their socks in the afternoon.But, what about putting on a differentcombination—say, going from thick tomedium-weight, or medium to light?And, as the weeks go by and miles passunderfoot, what happens to feet? Don’tthey change? Don’t soles thicken, andmuscles strengthen and enlarge? It seemsobvious that they must, just as waistlinesshrink and belts need tightening.Hikers should listen to their feet. Ifthey hear complaints, the easiest thing todo is to change, not just to dry socks,but to a thinner or thicker combinationthat will alleviate either looseness ortightness. In this way, blisters may beavoided. Certainly, greater comfort willbe achieved.Richard GrunebaumNew York, N.Y.Hiker museumThe museum of the A.T. is, indeed, longoverdue. Not only have many of theolder generation passed on, but those stillwith us have, in some cases, been forcedto discard their old equipment, for onereason or another. I know of several suchcases. I’m one myself.While I’ve never hiked the entire A.T.,I did own gear of the type used in formeryears by those who did. I know severalpersons who died in the last few decadeswho owned, at the time of their deaths, agood amount of hiking gear of the typeused circa 1920–1940. One item was aDavid T. Abercrombie mountain tent, apopular trail tent of the day. It weighedless than four pounds. I’m sure someitems of interest to the museum are outthere somewhere.As for the museum’s location, HarpersFerry? Perhaps, but I’d strongly urge thatserious consideration be given to the areaaround New York City. People from allover the world land at the airports in thevicinity. Some of them are hikers. Also,much of the pioneer <strong>Trail</strong>-building workwas done in the area, and many of the eldersof the tribe made the city or itsThis is my last opportunity to speak to the full membership of the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> Conference as its chair. Allow me to say, at the outset, whata privilege it has been to have had the opportunity to serve such a singularmission as caring for the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>. In this final essay, I wantto focus on what has long been called the “soul” of the <strong>Trail</strong>, “the livingstewardship of the volunteers and workers of the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> community.”At Conference ’95, after the Board election, individuals approached me with aconcern over relationships between the <strong>Trail</strong>-maintaining clubs and the Conference—boththe staff and the Board. A memorandum of understanding between ATCand the clubs was my first formal attempt to improve communications, but muchremains to be done. My twenty-two-year tenure on the Board has seen an expansionof the ATC’s professional staff from nearly zero to more than forty-five. I’ve beenboth excited and occasionally dismayed by this evolution, but am also able to placeit in the context of events that have overtakenthe <strong>Trail</strong> since 1979. Although the National <strong>Trail</strong>sThe soulof the <strong>Trail</strong>System Act was passed in 1968, it was not until1978 that the National Park Service became seriousabout protecting the <strong>Trail</strong>. The 1984 delegationagreement—returning most <strong>Trail</strong> responsibilitiesto ATC—was an extraordinary expression ofagency confidence in volunteer abilities that hasyet to be completely justified. Expansion of the ATC staff has been a natural reactionto the complex partnerships that have grown far beyond the traditionalrelationships between ATC and <strong>Trail</strong>-maintaining clubs and the challenges of publicland stewardship and management standards that go far beyond the requirementsof simpler times. Change is seldom welcome. The change in the <strong>Trail</strong> communityhas been profound. We all face the challenge of nurturing the soul of the <strong>Trail</strong> in theface of that change.In 1995, the Board of Managers adopted a policy on managing the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> for a primitive experience. The policy offers five questions that <strong>Trail</strong> managerscan use to test a management action against the goal of retaining the <strong>Trail</strong>’s primitivecharacter:1. Will this action or program protect the A.T.?2. Can this be done in a less obtrusive manner?3. Does this action unnecessarily sacrifice aspects of the <strong>Trail</strong> that provide solitudeor that challenge hikers’ skills or stamina?4. Could this action, either by itself or in concert with other actions, result in aninappropriate diminution of the primitive quality of the <strong>Trail</strong>?5. Will this action help to ensure that future generations of hikers will be able toenjoy a primitive recreational experience on the A.T.?Those five questions challenge <strong>Trail</strong> managers to carefully consider actions thatmight threaten the <strong>Trail</strong> experience. But, what of threats to the managers themselves?I have asked the staff to apply this test to their planning and daily work:“Would this action, policy, or staff posture work to support and enhance volunteerismor to discourage, even replace it?” I have asked them, especially, to consider howATC’s efforts can create an environment within which volunteers can achieve theirhighest potentials and to avoid reducing volunteer motivation by doing things thatcan perfectly well be done by volunteers, even if it takes a little longer. Similarly, Ichallenge volunteers to carefully distinguish between tasks that are best left toprofessionals and those that are suited to volunteer accomplishment. Collectively,Continued on next pageContinued on next pageAPPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 5

Shelter RegisterContinued from previous pageenvirons their home. And, lastly, the firstsection of the A.T. was laid out and blazednorth of the city in Harriman State Park.Some years ago, around 1965, while I wasdoing <strong>Trail</strong> work on that original section,I scraped down a white A.T. blaze withmy hunting knife to smooth the surface.In doing so, I uncovered yellow paint—the first official color used to mark the<strong>Trail</strong>. Even then, it had been long discontinued.I never after uncovered anothersuch marking.Robert SchulzRichmond Hill, N.Y.Trekking polesThe argument against trekking polesreminds me of the argument againstlug-soled hiking boots of a few years back.Does anyone now not wear lug soles?We need a little perspective. An <strong>ATN</strong>reader complains about the scars trekkingpoles leave on rocks. What about the scarof 2,100-plus miles the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>leaves on the Earth?We all advocate the Leave No Traceethic, but we buy high-tech gear madein countries with environmental policiesthat make clear-cutting look low-impact.We drive cars bigger than they need tobe, because they’re convenient. We driveFrom the Chair . . .Continued from previous pagemore than we need tofor pleasure or so wedon’t have to live nearour work. We live inhouses bigger thanwe need to, in orderto show off or limitinteraction with ourfamilies. We overheatand overcool thosehouses. We destroyhabitat to create farmsand drain aquifers to irrigatethem and damrivers for the power torun them, so we canhave a wide variety ofproduce without regardto where we live or thegrowing season of thosefruits and vegetables.And, I don’t objectto any of it. In fact, Iparticipate in all of it.What I object to is theself-righteous hypocrisy.By the way, I hikewith a walking staff Imade myself, tipped with a bit of tire.Sky ColeRidgefield, Conn.the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conference staff represents the greatest repository of knowledgein the United States, if not the world, on how professionals can work effectivelywith volunteer trail stewards. I’m confident that the staff will continue to use thatknowledge for the good of the <strong>Trail</strong>. The task for volunteers will be to leverage thatknowledge, through volunteerism, to greatest advantage.The goals will not always be clear or easy to reach, but the target will still beimportant. In forestry, we work toward a “target forest” (now popularly known as a“desired future condition”), knowing that we will never achieve that goal. Forestsare simply too dynamic, and the future remains as uncertain as ever. The <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong>, its users, and its stewards are also dynamic, as are the natural andhuman-caused events that surround the <strong>Trail</strong> and its people. Your goal, and that ofthe staff, should be to continue to work towards a cooperative, mutually supportivemanagement system that is robust enough to weather the unknown and to bridgethe occasional frictions to which human relationships are inevitably prone. All ofus will learn as we go along and adjust accordingly.For all of you, as for me, the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> has been a long journey—andnone of us wants it to end. ♦Gene Espy?As you can see, it has taken me a longtime to respond to Eugene Espy’s letterin the September 1998 <strong>ATN</strong>. It tookme a long time to find the picture above.Is the man in the middle Mr. Espy duringhis 1951 thru-hike?In September of 1951, Dave Wallaceand I decided to climb Mt. Washingtonbefore the start of our senior year at theUniversity of Rochester. We started atCrawford Notch and climbed part way upto the first shelter and stayed the night.We then climbed to the top and starteddown the Great Gorge <strong>Trail</strong>. We lost trackof the cairns, so we stopped and rolled outour sleeping bags. Next morning, we wentstraight up, found the auto road, andwalked to the top. That was when we sawthis bearded gentleman, and people weresaying he was a thru-hiker.C. Diehl OttBedford, N.H.Editor’s Note: Gene Espy reported hikingthrough the Presidential Range on September8 and 9 of 1951. ♦6 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

Area of the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> near Bland, Virginia, whereproposed line will cross. (Map: National Park Service)AEP power line approvedfor southwest VirginiaAcontroversial high-voltageelectrical transmissionline across southwestVirginia was given the goaheadMay 31 by an importantstate regulatory board. Theline will cross the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> but will follow a routethat <strong>Trail</strong> supporters contendwill cause minimal disruptionto scenic areas along the corridor.The Virginia State CorporationCommission (SCC)approved construction ofAmerican Electric Power’s765,000-volt transmission linealong the so-called “Wyoming–JacksonsFerry Route,”which would cross the A.T.near Bland, Virginia, where the<strong>Trail</strong> bridges Interstate 77.The approved route will besubstituted for a route originallyfavored by the powercompany that would havecrossed the <strong>Trail</strong> in a scenicPAPER TRAILarea near McAfee Knob andSinking Creek Valley, in theJefferson National Forest.ATC, the Roanoke A.T. Club,and other <strong>Trail</strong> groups had opposedthat route.The approved “I-77 Route,”as <strong>Trail</strong> supporters call it,will begin in Wyoming County,West Virginia, crossing intoVirginia near Tazewell. Itwill extend across fifty-sevenmiles in Virginia throughTazewell, Bland, and Wythecounties, ending at JacksonsFerry, south of Pulaski, Virginia.The line still faces oppositionfrom citizens groupsthat have vowed to appealthe SCC decision. Elevenmiles that pass through theJefferson National Forestmust be approved by theUSDA Forest Service andNews from Harpers FerryContinued on page 27Rejected SUV marketingproject spurs debateAdecision in late March topull out of a deal to linkthe <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>Conference’s name with atwo-month sport-utilityvehicle(SUV) marketing campaignprompted the ATCBoard of Managers to debatewhether there should be a “litmustest” when organizationsand corporations offer to donatemoney in exchange forrecognition.The Board left the currentprocess in place, but membersdebated the issue—and thequestion of how involved theBoard should be in decidingspecific cases—for nearly anhour at its spring meeting inShepherdstown, West Virginia,April 29-30.The debate came onlyweeks after the Conferencebacked out of a $50,000 offerby a marketing firm promotinga new Chevrolet SUVmodel, the <strong>Trail</strong> Blazer. Thefirm would have publicizedthe Conference and its <strong>Trail</strong>maintainingclubs in connectionwith media eventspromoting the vehicle nearthe <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> in themid-Atlantic sates and NewEngland. After ATC withdrew,the Chevrolet events tookplace as scheduled, but withoutany mention of the Conferenceand clubs or a donation.In the past, ATC has selectivelylicensed its name and/or logo to companies sellingbottled water, books, and othermerchandise in exchange forcorporate donations. ExecutiveDirector Dave Startzellexplained that Conferencestaff members had taken theproposal to the Board’s executiveand internal reviewcommittees, which is beyondthe established procedure. Thecommittees gave it a greenlight.As <strong>Trail</strong>-maintaining clubswere asked by ATC to join itat the in-town events and beassociated with a sport-utilityvehicle, several of them objectedand refused to participate.A flurry of impassionede-mails and phone callsamong Board members ledATC Chair Dave Field to askStartzell to withdraw from theproject before it caused furtherdissension on the Board.“I would much rather nothave been in the position ofhaving to make a decision onthis,” Field told the Board inApril. “I asked him to withdrawfrom it not as a judgmenton the merits or lack of meritsof the deal. My concern wasthe health of the Board of Managersand what the effect ofintense dissent might be.”“We need some kind of twowaycommunication, so theBoard’s committees can getinput from the clubs,” arguedGlenn Scherer, one of theBoard members who had op-Continued on next pageAPPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 7

Paper <strong>Trail</strong>SUV project spurs debate…Continued from previous pageposed ATC’s association witha class of vehicles that hasbeen linked to air-pollutionproblems.“There’s a lot to be said forworking with clubs and communitiesand getting theclubs to ‘buy in’ on projectslike this,” Board memberCarl Demrow said. “But, Idon’t think we need anymore litmus tests. I’m disappointedthat we pulled out ofthe deal. I put my trust in theprofessional staff, the executivecommittee, and theinternal review committee.”“I would also be reticentto add further litmus tests,”Board member Sandy Marrasaid. She described howwomen’s advocacy organizationsshe’d worked withhad raised funds from manysources, including the PlayboyFoundation. “I don’tmean to imply that the endalways justifies the means,but there’s something to besaid for taking pleasure intaking that money and doingsomething positive with it.We’re sometimes going tohave strange bedfellowswhen it comes to raisingmoney for the Conference.”“I’m happy with the decisionthat was made to backaway,” Board memberSteven Smith said. “I didn’tlike the association with theSUV. I’m okay with havingChevrolet as a contributor,but I’m not okay with puttingour logo on their marketingprojects.”Daniel Chazin of the NewYork–New Jersey <strong>Trail</strong> Conferencesaid that his club’sdecision to oppose the deal,after it was announced,might have turned out differentlyif there had been moreinformation and more timeto consider it. “We wereshocked getting this newswithout any background information,”Chazin said.“The other thing said wasthat, if ATC’s getting$50,000, what do we get outof it? If you expect activeparticipation from clubs, youneed full disclosure aboutwhat the quid pro quo is.”“ATC’s budget has literallyhundreds of thousandsof dollars going into clubprograms and into <strong>Trail</strong>clubs, not to mention thework of ATC’s regional representatives,”responded BobProudman, the Conference’sdirector of <strong>Trail</strong> managementprograms. “I’ve arguedto clubs that, given oursubstantial federal fundingand the requirements thatentails, it’s important tomaintain a diversity of fundingsources.”Startzell said that opportunitiessuch as the Chevroletproject often requirefast action, which is whythey go to committees ratherthan the full Board of Managers,which meets twice ayear. One of the lessons ATClearned from the abortedproject, he said, is that manymembers of <strong>Trail</strong>-maintainingclubs don’t clearlyunderstand how the Conferenceworks, how it is funded,and why fund-raising devicessuch as the Chevrolet arrangementare important toATC’s ability to support clubmaintenance activities andother <strong>Trail</strong> programs. ♦ATC signs letter from hiker coalition lobbying against air pollutionThe <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conference has added its name to acoalition of hiking and conservation organizations petitioningfederal officials to toughen the federal Clean Air Act,Executive Director Dave Startzell announced in June.Startzell said that ATC had signed a letter sponsored bythe coalition, Hikers for Clean Air, to EPA AdministratorChristine Todd Whitman, urging tough enforcement of existingstandards affecting power-generating plants andrequesting her help in arranging a meeting with White Houseofficials.The letter noted that the organizations represent 200,000hikers who use the mountains of the eastern United Statesfor recreation and enjoyment and asks Whitman to “correctviolations of the federal Clean Air Act’s New Source Review(NSR) requirements applicable to electric power generatingplants.” Those requirements, it said, could force reductionsin air pollution that harm human communities, aquatic life,and forest ecosystems in the <strong>Appalachian</strong>s, Hudson Highlands,Catskills, Adirondacks, and White Mountains.The “New Source Review” requirements, which coal andenergy lobbyists want revoked, “simply require power plantowners to upgrade their air pollution-control measures wheneverthey undertake a major overhaul of a generating unit,”the letter said. Plants have been evading this requirement,the letter argued, leading to increases in asthma and emphysemaincidence rates, increased haze, acidified lakes andstreams, damaged mountain forests, and soils that have beenchemically altered.“Many utilities have made major modifications to‘grandfathered’ generating facilities that resulted in increasedgenerating capacity and higher levels of nitrogen oxides andsulfur dioxide emissions,” the letter said. “It is inaccurateand disingenuous for power-plant operators to characterizethese upgrades as ‘routine maintenance’ measures.”Assertions by the coal lobby that the regulations harmthe nation’s energy supply are false, the letter said. “Indeed,three utilities have signed tentative or final settlement agreementsthat will result in deep pollution reductions withoutcreating a shortage of electric power supply.”Abandoning the rules and existing enforcement actionswould send a message “that environmental laws may be subvertedand that vitally necessary measures to improve publichealth, air and water quality will be sacrificed to politicalexpediency,” the letter said. ♦8 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

Paper <strong>Trail</strong>“I just loved the woods”An interview with outgoing ATC Chair Dave FieldEDITOR’S NOTE: Even before hewas elected ATC chair in1995, David B. Field has beenone of the <strong>Trail</strong>’s most activeand articulate advocates.Brian Fitzgerald of Vermonthas been nominated to succeedhim as chair at thissummer’s biennial conference.As Field’s third termcomes to an end, <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong>way News asked him tolook back on his many yearsof volunteer work with the<strong>Trail</strong> project and to talk a littlebit about the changes he’dseen—both in the project andin his own thinking about it.<strong>ATN</strong>: Do you remember theday that you first discoveredthe <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>?Field: Distinctly! It was springof 1955, and my olderbrother had been talkingwith a group of us whopalled around together inthose days. We were interestedin topographic maps,and he had seen a topo mapnear our town that showedthe <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> andsuggested that we go therefor a hike.<strong>ATN</strong>: What did you find whenyou got there?Field: Ah, that’s where it allstarted. You see, we chose tohike a side trail of the A.T.,the Bigelow Range <strong>Trail</strong>, inthe Bigelow Range in Maine.It was six miles long and ledover the range to HornsPond. I distinctly rememberDave Field (center) in November 2000 with ATC Treasurer Ken Honick (left) and Brian Fitzgerald(right), nominated to succeed Field as chair of the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conference.how we joked aboutwhether we could hike sixmiles in a day. It took us twodays! We’d never done anyserious backpacking, andwe’d packed outrageously,carrying stuff that was unbelievable—oneguy packeda bugle, I think, and someonebrought a dozen fresheggs, which someone elsepromptly sat on. But, whatwe had not counted on at allwas that this range was devastatedby Hurricane Carolin 1954—the eye had goneright through the center ofMaine and blown the top ofthe mountain flat. We foundourselves crawling underneathbig piles of blowdownsalong a <strong>Trail</strong> whereyou could barely find anyblazes. At one point, wecame to the edge of a cliffwith no idea of where the<strong>Trail</strong> was and started downin the fog, unable to see anything.We decided to comeback up, which was a goodthing, because it was a sixtyfootdrop. The reaction ofthe group to all this was thatsomebody really ought toclear that trail. So, we wenthome for axes, crosscutsaws, and whatever tools wecould get, then hauled themup the mountain and triedto clear trail.<strong>ATN</strong>: You did this withoutasking permission?Field: We’d never heard of the<strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conferenceor of the Maine <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> Club. At thecampsite, there was a brasscanister in which registerswere kept, so we wrote inthe register and said whatwe were doing. We keptcoming back—one day wetook down 250 blowdowns.With every trip we made outthere, as we did more work,we wrote it down and put itin the canister. By and by,my brother got a letter fromthe <strong>Trail</strong> overseer for thesection, saying, “Would youlike to join the Maine A.TClub?”<strong>ATN</strong>: So, which came first,your love of trails and hik-APPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 9

Paper <strong>Trail</strong>ing or your interest in forestry,which became yourprofession?Field: It’s a chicken-egg problem—Ijust loved the woods,and I think they go hand inhand. I was thinking of awoods-related career anyway,and my dad was in severalbusinesses involvingthe forest. My first forestryjob was in the White MountainNational Forest, whereI ran a ridgerunner program:One day I’d be marking timber,the next dealing withridgerunners, and on anotherday I’d be pulling bodiesoff Mt. Washington.<strong>ATN</strong>: Do you think it’s stillpossible for someone to fallin love with the woods inthe way that you did?Field: It’s still possible—andlikely—although I thinkthat now people come to the<strong>Trail</strong> from many differentbackgrounds. Hunting, fishing,and the woods are stilla part of the living environmentthat I experiencedgrowing up, and it’s certainlypossible there. Andthen you have people whoseparents sent them to a youthcamp in the Maine woods,or professional forestrygraduates who’ve come tothe <strong>Trail</strong> from that direction—I’vehad a number ofmy forestry students who’vegone out and hiked thewhole <strong>Trail</strong>. It’s interestingthat resource professionalswere heavily involved in thefounding of the <strong>Trail</strong> and areI think of the long-distance European hikingtrails as the A.T.’s only counterparts, becauseof the geographical and the jurisdictionalcomplexities. It’s one of the most fascinatingparts of the whole enterprise.still heavily involved on theBoard and in the Conferencetoday. But, now they’ve beenjoined by more people froman urban or suburban background.Where you see thebiggest difference in theirbackgrounds is in their attitudestoward certain policies.Those whose backgroundhad less of a connectionwith the land tend tofavor stricter preservation.Those, like myself, whosebackground is closer to theland are more likely to thinkabout it in terms of multiplecompatible uses.<strong>ATN</strong>: Has the way that youlook at the <strong>Trail</strong> and the roleof clubs changed over theyears?Field: Indeed it has. It hasevolved slowly, though. Thebiggest transition was evolvingfrom a near-anarchist asfar as <strong>Trail</strong> policies are concernedto more of a “teamplayer.” There’s an attitudein Maine that favors independence,being left alone,being allowed to be creative,and not following themanual so much. That wasme, and I was simply a <strong>Trail</strong>maintainer until 1968, responsiblefor the same sectionof <strong>Trail</strong> that I maintaintoday.<strong>ATN</strong>: That’s when you firstbecame involved with otherclub activities?Field: That’s when I agreed tobecome the club’s overseerfor western Maine, whichmeant acting as liaison between<strong>Trail</strong> maintainers andofficers of the club. I heldthat position for about tenyears, and that’s when I becamepart of the organization.After that, I was presidentof the club for ten yearsand was elected to the ATCboard in 1979; I then servedas secretary for ten years andvice chair for New Englandfor two years before beingelected chair in 1995.<strong>ATN</strong>: What were some of theprojects you worked on?Field: I think the real contributionI made to the <strong>Trail</strong>was in the club’s work on relocating180 miles in Maine.I designed a lot of that andhelped establish most of the<strong>Trail</strong> corridor in Maine. Allof that stuff confronted mewith the need to think aboutthings other than my firstlove—<strong>Trail</strong> maintenance.Clearly, as I became moreinvolved with ATC, morethan with the Maine A.T.Club, it faced me with thenecessity of being concernedabout <strong>Trail</strong>wide policy,turning my focus awayfrom Maine and toward thethings that are common toall clubs, from the GeorgiaA.T. Club to the Maine A.T.Club. And, I became awareof the things that were verydifferent. Like most <strong>Trail</strong>clubpresidents, we mostlytried to figure out how tokeep the ATC off our backs.I had no appreciation until Igot involved with the Boardof how different the environmentis for the differentclubs. In Maine, we neverhad any involvement withthe Forest Service andthe National Park Service.There is no national forestin Maine crossed by the<strong>Trail</strong> and no national parkcrossed by the <strong>Trail</strong>. This isa dramatically different situationthan, say, the GeorgiaA.T. Club, or the Nantahalaclub, which work so closelywith the Forest Service that,in times past, it sometimesseemed as if they neededpermission just to paintblazes.<strong>ATN</strong>: Has that attitudechanged?Field: I hope so. One of the realcatalysts was the 1984delegation agreement. InMaine, we were suddenlydealing with National ParkService and state land, andall of a sudden we had toanswer to somebody. It laiddown the force and authorityof the Code of FederalRegulations on what wewere doing. We had no experiencewith that. Even forthe clubs in the South, the1984 agreement made abig difference in how theyworked with the parks andnational forests. That’s stillevolving today. The parksare sort of sovereign, especiallythe older parks, andthe rules and regulationsgoverning the clubs in thoseparks are different. There’snow a continuing effort toget the agencies—from theChattahoochee NationalForest to the White MountainNational Forest tothe various national parkunits—to behave and to positionthemselves towardthe A.T. with a little moreconsistency. It’s a fascinatingproject. There’s nothinglike it in the world. I thinkof the long-distance Europeanhiking trails as theA.T.’s only counterparts,because of the geographicaland the jurisdictional complexities.It’s one of themost fascinating parts of thewhole enterprise.10 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

Paper <strong>Trail</strong><strong>ATN</strong>: What will that relationshipamong the clubs, ATC,and the management agenciesbe like in ten years?Field: I honestly believe therelationships will continueto strengthen. I’m reallypleading with both sides toappreciate each other and towork together, so that theorganism as a whole cancontribute to the furtheranceof the <strong>Trail</strong>.<strong>ATN</strong>: What do you worryabout in the next ten years?Field: I remain concernedabout the growth of theConference staff, how thatcan be supported, andwhether staff efforts mightbe replacing volunteer efforts.At the same time, Irecognize that, under thedelegation agreement, thereare things that volunteerscan’t do or don’t want to do.I feel confident that the relationshipswill strengthenand ATC will continue to beable to cope with the 900-pound gorilla that is thePark Service, which is reallythe best partner we couldever have had. The NPSpeople working with theA.T., from Dave Richie toPam Underhill, have beenenormously supportive, buta federal agency is a federalagency. A continually improvingworking relationshipis going to be essentialto retaining our identity. Wehave been told by heads ofnational parks that we can’tpossibly succeed in doingthis. Partly it’s a matter ofmaintaining the integrity ofthe dream and the organizationas a whole.<strong>ATN</strong>: What are some otherchallenges?Field: I don’t have an answerfor one of the central dilemmasabout the future of the<strong>Trail</strong>, the question of use—its physical and social carryingcapacity. I was reallyfrustrated at ATC’s brief effort,working with the ParkService, to deal with the“use question.” We organizeda committee and met,but we realized that we justweren’t going to get there.That remains one of thegreatest dilemmas and challengesfor the future, and it’sgoing to take an enormousamount of creativity on thepart of the Conference todeal with that. I used to goup on Memorial Day weekendto do <strong>Trail</strong> maintenanceand would never see anothersoul. This year, I saw thirtysixpeople. The shelter inmy section holds six, withcomfortable tenting spacefor three tents. Twenty-fivewere there.It’s still a huge trail, there are still vast expanses—milesand miles—where you can workall day and not see another person.<strong>ATN</strong>: With all the requirementsand regulations thatthe management agreemententails, can working on the<strong>Trail</strong> still be fun for volunteers?Field: Yes. It’s still a huge trail,there are still vast expanses—milesand miles—where you can work all dayand not see another person.When you do corridor monitoring,checking the boundaries,you can walk all dayand not see another person.But, the work has changed.When I started out, wedidn’t even try to clear allthe brush and blowdowns,which is why the <strong>Trail</strong> wasblazed so extensively. Evenso, there’s still all the opportunityfor fun and solitudeand the enjoyment of trailwork that in many waysisn’t that different fromwhat it was 50 years ago.<strong>ATN</strong>: Do you see the relationshipbetween maintainersand hikers changing? Evennow, some Board membershave strong feelings aboutthru-hikers and all the attentionthey get.Field: We will continue to recognizethat thru-hikers area critically important minorityof <strong>Trail</strong> users. Wehave not designed or maintainedthe <strong>Trail</strong> for thru-hikersor provided facilities forthem—ATC has simplynever done that. At the outset,the original trail-blazersand builders had the ideathat what was differentabout the A.T. was the opportunitiesit provided for along hike, but, even then, itwas not the sort of thingthru-hikers do. For instance,shelters were built a comfortableday’s hike apart, butit was a 10- to 15-mile day,which is well shy of themileage of a typical thruhiker.In fact, we made the<strong>Trail</strong> in Maine a muchharder <strong>Trail</strong> for thru-hikersby moving it off the woodsroads and putting it on theridges. It slowed the thruhikersdown, and somedidn’t like it at all, butwe felt that routing the <strong>Trail</strong>to beautiful places was moreimportant than providing aIt’s obvious who we manage the <strong>Trail</strong> for.Thru-hikers are a critical minority,however, and when you talk about the use ofthe <strong>Trail</strong> … you have to deal withthe full spectrum of <strong>Trail</strong> experience.speedway for thru-hikers.It’s obvious who we managethe <strong>Trail</strong> for. Thru-hikers area critical minority, however,and, when you talk aboutthe use of the <strong>Trail</strong>, thevalue of the <strong>Trail</strong>, you haveto deal with the full spectrumof <strong>Trail</strong> experience.There has to be somethingrelevant to everyone at everypoint along that spectrum.<strong>ATN</strong>: When you look back atthe beginning of your termas chair, what were some ofthe things you thought mostimportant to accomplish?Field: I had a real fixation onvolunteerism and hoped Icould do something tostrengthen the interest ofvolunteers in participatingin the <strong>Trail</strong> project. I hopeI’ve at least kept people’sinterest up. I wanted tobuild a stronger relationshipbetween the Conference andclubs. A basic goal was justdoing what I could, as oneof many players, in strengtheningthe partnership betweenATC, the clubs, andthe agencies. It is so hideouslycomplex, and it issomething that has to beconstantly worked at. And,Continued on page 27APPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 11

SIDEHILLNews from clubs and government agencies“<strong>Trail</strong> Days” <strong>2001</strong>Damascus festival highlights the work of <strong>Trail</strong> volunteersScenes from <strong>Trail</strong> Days (clockwise from top):ATC volunteers march in the hiker parade;the only working train in Damascus; at theboot-fitting clinic; “P.O.-blazing” becomesthe latest thru-hiking craze; ATC volunteerssign up new members at the Conferencebooth; crowds gather for the talent show.(ATC photos: Laurie Potteiger)By John KillamHikers attend <strong>Trail</strong> Days inDamascus, Virginia, tohave fun, to celebratetheir hike, and to exult in thecollective energy that accompaniesthe marvelous undertakingof hiking the A.T. I firstheard of the event when it wasbegun in 1987 and attendedmy first one in 1995 during along-distance hike. I wasn’tdisappointed. I’ve missed onlyone event in the years since.This year, though, thetheme at <strong>Trail</strong> Days was “Volunteer<strong>Trail</strong> Maintainers:They Make It Possible AndPassable.” I am a hiker, butI’m also a volunteer, and Iwas excited to see so muchparticipation by ATC in theevent—something that hasn’talways happened in the past.Former ATC Chair RayHunt led a roundtable discussionon volunteer <strong>Trail</strong> work,volunteers and staff marchedin the parade carrying trail-maintenance tools and placardshighlighting ATC initiatives,volunteers and staffmembers manned two informationbooths for the benefitof hikers and the general public,Mary Sue Roach (one offourteen ATC Land Trust localcoordinators) and LauriePotteiger (information servicescoordinator) wereemcees of the hiker talentshow, and, to my knowledge,a real “first” occurred whenATC Board member SandraMarra performed in the talentcontest.For many thru-hikers, thiswas their first in-person contactwith ATC as they browsedat the information booths andchatted with the staff and volunteers.Hiker/volunteer PhilAbruzzese, hostel owner and<strong>Trail</strong>-maintainer Bob Peoples,and members of the TennesseeEastman Hiking Club challengedthe hikers to travel toContinued on next page12 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

SidehillCorridor countdowna work site on Roan Mountainand spread rock and gravel ona section of very muddy tread.Would they? You bet. On Sunday,the final day of <strong>Trail</strong> Days,twenty-five people worked onthe project. On Monday, thiryfourworkers participated.According to reports, volunteersspread about fourteentons of rock and gravel on thedesignated Round Bald sectionof <strong>Trail</strong>.At ATC’s informationbooths, 281 persons completeda five-question multiplechoicequiz about volunteeringand ATC, which qualifiedthem for a drawing for prizesdonated by manufacturers ofbackpacking gear. Some 363participants requested informationabout ATC and its programs.In addition, sixty-twonew members signed up. Volunteers,staff members, andhikers assisted in the donationand collection of a substantialamount of money to help thetown of Damascus defray thecost of sponsoring <strong>Trail</strong> Days,which allowed the town to dispensewith a fee they hadplanned to charge to campers.Hiking and <strong>Trail</strong> volunteerwork can, and should, go handin-hand.For me, the celebrationof both hiking and volunteeringis at the heart of any<strong>Trail</strong> Days festival.John Killam is a longtime ATCvolunteer who has recordedmore than 430 volunteer hoursin <strong>2001</strong> alone. ♦IT WAS THE HOPE OF CONGRESS, THE FEDERAL ADMINISTRATION,and the <strong>Trail</strong> community that the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>could be pronounced “fully protected” by the end of the centuryon December, 31, 2000. Now, it appears that the NationalPark Service portion of the protection program could be completedin <strong>2001</strong>, with the Forest Service finishing its portion thefollowing year. Footpath tracts are completely acquired in fourof the fourteen A.T. states, but many acres of protective corridorremain privately held. Here is where the federal and stateagencies stood as of February <strong>2001</strong> in terms of footpath miles(0.6 of one percent) and adjoining acreage (4.3 percent) left toacquire:States Map Miles AcresMaine 1.9 350New Hampshire 0.2 18Vermont 0.0 42Massachusetts 0.1 362Connecticut 0.7 243New York 0.1 302New Jersey 0.0 79Pennsylvania 2.8 214Maryland 3.5 681Virginia 4.9 1,901West Virginia/Va. 0.0 0N.C./Tennessee 3.0 3,540Georgia 0.0 513Total 17.2 8,156George Zoebelein ofGrandview-on-Hudson,New York, who servedtwo terms as chair of the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> Conference,died May 13 after an illness.He was 65.Mr. Zoebelein’s involvementwith the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> began as a member of theNew York–New Jersey <strong>Trail</strong>Conference, which he servedas president from 1964 to 1970and 1974 to 1975. He alsoserved as an early editor of theNew York Walk Book. He wasnamed an honorary member ofthe NY–NJ TC in 1989.He was first elected chairof ATC in 1975 and servedthrough 1979. After his secondterm ended, he remained anactive participant as a chairemeritus on the Board of Managersand participated in theBoard’s November 2000 meetingin Harpers Ferry.“The Conference was goingthrough a transitional periodduring the time he was chair,”recalled Charles Pugh, whosucceeded Zoebelein in 1979.“I was a vice chair at the time,and the Conference was goingfrom what had been sort of a‘desk drawer operation’ to aprofessional organization thathad national standing.”Mr. Zoebelein was an accountantand a businessman,Mr. Pugh recalled, and theConference needed his credibilityat a time when, underPresident Jimmy Carter, theNational Park Service and U.S.Forest Service were starting towork more closely with ATCand to begin the long processof land acquisition for the<strong>Trail</strong>. The first NPS acquisitionof A.T. land occurredin New York late in Mr.Zoebelein’s tenure, in 1979.Board member CharlesSloan recalled how Zoebeleininsisted that the Conferencehave legal counsel in additionto a good accounting system.“He brought a real businessapproach to ATC that wasneeded in those days,” Mr.Sloan said. “I became thatlegal counsel and have continuedto work for ATC since thattime.”That period saw an intensifiedeffort at getting the<strong>Trail</strong> off roads and onto protectedroutes, particularly inparts of Virginia and Pennsylvaniawhere it passedthrough populous areas, Mr.Pugh said. <strong>Trail</strong> use wasgrowing but had yet to explodeas it would during thelate 1980s and 1990s.“We were in the process ofnegotiating the first managementagreements with theNPS,” Mr. Pugh said. “Thewhole concept of having volunteerswork with the ParkService and have some fundingfrom the government wasvery new, and most of the governmentpeople had neverheard or thought of such athing. It was hard to sell theprofessional managers in thePark Service on the idea ofturning it over to a wholebunch of volunteer clubs overAPPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 13DeathsGeorge Zoebelein, formerATC ChairContinued on page 28

SidehillPolicy would ban advertisinginside <strong>Trail</strong> corridorAdraft policy being consideredby the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> Conference wouldexclude advertising, includingsigns, notes, and businesscards, from the corridor of landaround the <strong>Trail</strong> and along the<strong>Trail</strong> itself. The policy instructsmaintainers to removeads along the <strong>Trail</strong> for hostels,outfitters, organized “<strong>Trail</strong>magic,” and related activities.The policy was first discussedat management committeemeetings last fall forthe New England and mid-Atlanticregions and again inMarch at the meeting of themanagement committee forthe southern region. ATC isnow seeking comment on thedraft policy from clubs andConference members beforethe Board of Managers voteson it in November.The policy defines advertisingas “posting materials suchas signs, notes, or businesscards; or distributing flyers,brochures, or similar materialsdesigned to call specificservices, both commercial andnoncommercial, to the attentionof hikers.” It exemptsmaterials that promote membershipin ATC or <strong>Trail</strong>maintainingclubs or participationin volunteer <strong>Trail</strong> managementactivities, as well asmaterials such as sponsorshipsigns that recognize commercialor noncommercialentities that support the <strong>Trail</strong>.On National Park Serviceand USDA Forest Servicelands, the policy instructs<strong>Trail</strong> maintainers (with theconcurrence of the agencies) toremove any advertisementsposted within the <strong>Trail</strong>, “includingthose on signs orbulletin boards, or in sheltersor other structures.” On landsmanaged by other agencies (includingstate forest, park, andtransportation departments),the policy encourages clubs towork with those agencies todevelop and implement policiesthat prohibit advertisingwithin the <strong>Trail</strong> corridor andauthorize <strong>Trail</strong> maintainers toremove unauthorized signs.Instead of advertising alongthe <strong>Trail</strong>, the policy suggestsinformation on hiker servicesto be included in publicationsand other ATC hiker informationsources. If a <strong>Trail</strong>maintainingclub determinesthat it is vital to let hikersknow about the types ofservices available in nearbycommunities, and othermeans of getting the informationout have failed, the clubcan post generic signs at roadcrossings indicating the typesof services available. The signscan also show the distance anddirection of the service, butnot the names of specific businessesor establishments.“ATC recognizes that manyA.T. hikers value the services(e.g., lodging, restaurants, outfitters,and shuttles) that areavailable in many communitiesalong the <strong>Trail</strong>,” the draftpolicy states. “These servicesmay be commercial in natureor offered by so-called ‘<strong>Trail</strong>Angels’ who provide free assistanceto hikers. In either case,Gypsy moths prompt pesticide sprayingInfestations of gypsy moths along the A.T. have led landmanagementagencies to begin a campaign of pesticidespraying in several <strong>Trail</strong> states this year.The moths, which consume all the leaves of infested trees,killing them by depriving them of sunlight and nutrition, havebeen identified in eleven of the fourteen states that the <strong>Trail</strong>passes through. Millions of acres of trees are defoliated by themoths each year.According to Bob Proudman, director of ATC’s <strong>Trail</strong>-managementprograms, several areas along the A.T. have beensprayed this spring, using both fixed-wing aircraft and helicoptersin an attempt to suppress the moth population.Proudman said that land managers from the Maryland Departmentof Agriculture, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park,and Clarke County, Virginia, to name a few, recently sprayedfor gypsy moths using a variety of chemicals and methods.In Maryland, Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), a naturally occurringorganism that is poisonous to moths and butterflies, wasused along South Mountain at the request of the National ParkService <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Park Office. State land managerspreferred Difubenzuron (Dimilin), a chemical that interfereswith gypsy-moth growth, but agreed to use the more benignBt, Proudman said. Park officials at the Harpers Ferry NHPused kurstaki (Gypchek), a formulation of a naturally occurringgypsy-moth virus. Dimilin was used in Clarke County,adjacent to federal <strong>Trail</strong> lands.According to Proudman, each of the three methods has advantagesand disadvantages, but none poses a threat to hikerhealth. Continuing education and management are keys tostemming the tide of the rising gypsy-moth population alongthe <strong>Appalachian</strong> Mountains and its inevitable effects on treecover, he said.The gypsy moth, imported from Europe to Medford, Massachusetts,in 1869 by Leopold Trouvelot, now ranges north toCanada, west to Wisconsin, and south to North Carolina. Hikersoften notice moth infestations as an area teeming withsmall, greenish caterpillars on trees and on gossamer threadshanging from branches of defoliated trees.the contribution they make tothe overall experience of hikingthe A.T. is important tomany hikers, especially longdistancehikers.“In order to maintain thenatural character of the A.T.corridor, it is the policy of the<strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conferencethat advertising is incompatiblewith the <strong>Trail</strong> and shouldnot take place within theA.T. corridor. The availabilityof hiker services outside ofthe <strong>Trail</strong> corridor should bepublicized through othermeans, such as publicationsand <strong>Trail</strong>head signs,” thepolicy states.“ ♦14 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

SidehillNational Park Service announces <strong>2001</strong> service awards for <strong>Trail</strong> volunteersThe <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Park Office of the National ParkService has named eleven recipients of its new “GoldenService Award,” which recognizes fifty years of activevolunteer service on the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>. Anothereighty-five volunteers were named recipients of the new NPS“Silver Service Award,” which recognizes twenty-five yearsof active volunteer service.The new awards are intended to be presented at each <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> Conference biennial meeting and recognize acontinuing volunteer commitment to the A.T. on lands administeredby the National Park Service and USDA ForestService. This year’s meeting, in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania,was <strong>July</strong> 13–20.Georgia A.T. ClubGolden Service AwardWhit BensonEugene EspyArline SlackSilver Service AwardHarold ArnovitzGale BensonJoe BoydHerb DanielMargaret DrummondMary EidsonG. Dudley EgglestonJune EngleGeorge GalphinJudy GalphinGeorge GoldmanClark HillGeorge Owen, Jr.Marty RubinNancy ShofnerGinny SlackRosalind Van LandinghamGrant WilkinsNatural Bridge A.T. ClubGolden Service AwardDorothy BlissSilver Service AwardEd PageTennessee Eastman Hiking andClimbing ClubGolden Service AwardV. Collins ChewWyoming to host trail groups in <strong>August</strong>The Partnership for the National <strong>Trail</strong>s System will convenethe 7th Conference on National Scenic and Historic <strong>Trail</strong>s,<strong>August</strong> 17-21, at the Radisson Hotel in Casper, Wyoming.The conference theme, “Howdy Pardner—Strong PartnershipsMake Great National <strong>Trail</strong>s”—invites participants tonurture a culture of collaboration and to strengthen and celebratethe partnerships so essential to the national trailssystem. The program focuses on new initiatives such as theUSDA Forest Service’s recreation agenda and the National ParkService’s cultural resources initiative, as well as on ongoingprograms. Workshops on trail-resource protection, funding,education, and volunteerism will be offered along with fieldtrips, hikes, and interpretive tours in Wyoming, as well asinformal meetings among trail organizations.For information and registration materials, contact GaryWerner, Partnership for the National <strong>Trail</strong>s System, (608) 249-7870, .Frank OglesbyRaymond HuntSilver Service AwardSteve BanksBruce CunninghamMary CunninghamJohn KeiferGary LuttrellCris MoorehouseTheona MoorehouseDarrol NickelsJeff SirolaJohn ThompsonFrank WilliamsEd OliverBlue Mountain Eagle ClimbingClubGolden Service AwardJune FisherSilver Service AwardEsther GearyPaul Geary, Jr.Bruce HomanLarry KramerPaul KurtzBetty LehmanAnn LehmanAndy McClayDonald MillerGeraldine ReedCatherine ShadeSandy ShollenbergerGeorge ShollenbergerEdwina SpeidelMortimer WeislerJean WeislerOld Dominion A.T. ClubGolden Service AwardHenry HarmanSilver Service AwardJohn FarmerJack WilliamsNantahala Hiking ClubGolden Service AwardSally KeslerSusquehanna A.T. ClubGolden Service AwardEarl ShafferSilver Service AwardAnna KinterRalph KinterRoanoke A.T. ClubSilver Service AwardLinda AkersZetta CampbellBill GordgeSiegfried KolmstetterCharles ParryMountain Club of MarylandSilver Service AwardSue BayleyTerry EckardJohn Eckard, Jr.Paul IvesLarry KellyJastrow LevinTed SandersonEleanor SewellMount Rogers A.T. ClubSilver Service AwardCornelius BoothGene CunninghamLouise HallGilda KellerBlair KellerG.A. “Mac” McDanielVirginia PrestonRobert WolfeJoanna WolfeSmoky Mountains Hiking ClubSilver Service AwardCarol CoffeyRichard KetellePiedmont A.T. HikersSilver Service AwardBarbara CouncilHenry FordDoris FordHollyce KirklandKen RoseMaine A.T. ClubSilver Service AwardDavid FieldNew York–New Jersey <strong>Trail</strong>ConferenceSilver Service AwardJane GeislerTidewater A.T. ClubSilver Service AwardOtey SheltonAllentown Hiking ClubSilver Service AwardRichard SnyderBarbara WiemannAPPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 15

TREELINENews from along the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>GarveyShelterdedicationA crowd of about onehundred turned out April29 to witness thededication of the new EdGarvey Memorial Shelter,north of the PotomacRiver in Maryland, nearWeverton Cliffs. The largetwo-level shelter was builtwith mostly donatedmaterials and labor fromthe Potomac A.T. Club,hikers, volunteers fromthe community and fromthe deaf community ofGallaudet University. TheBaltimore Sun reportsthat the project cost anestimated $10,000 tocomplete, and was paidfor by donations andgrants, including a grantfrom ATC. The ceremonyfeatured an impassionedaddress in American SignLanguage by Frank Turk,Sr. (center photo), whoseson, Frank Turk, Jr.,supervised the project.Garvey’s daughter, Sharon(lower right), whodesigned the shelter,recalled her father’s longlove affair with the A.T.and paid tribute to thevolunteers. (ATC photos:Robert Rubin)16 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

TreelineGeocaching: twenty-first-century treasure-hunting?By David ReusThat Tupperware containerfilled with goodies youjust stumbled across maynot be the “<strong>Trail</strong> magic” leftfor a grateful A.T. hiker thatyou think it is. It just may bea “geocache.”Geocaching, described as“equal parts sport, culture, andtreasure hunt,” involves participantshiding a cache (astash of goods) in a remote locationand recording its exactposition using a hand-held globalpositioning system (GPS)unit. The coordinates, alongwith a few helpful hints, arethen posted on the World WideWeb (is a popular site) for other GPSwieldinggeocachers to look upand then hunt for. Armed witha GPS unit, the pursuer mustnavigate a route to the site andthen search for the hiddencache.It’s actually a modern variationon an old idea called“letterboxing,” which tracesits roots all the way backto 1854 to a remote partof Dartmoor, England. Thedifference between the two activitiesis that geocachingrelies on using GPS to locatethe cache, whereas letterboxingrequires the participantto decipher a riddle or setof clues to find the locationof the letterbox. There areabout 1,000 letterboxes inNorth America, with at leasteighteen located along the<strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>.Geocaches are usuallyhoused in a waterproof plasticcontainer and may contain anynumber of items, from themundane to the extraordinary.The unofficial rules dictatethat you may take an itemfrom the stash if you leavesomething of your own in itsplace, so that the item or itemsin the cache are in a continualflux—you never know whatyou’ll find. There is also a logbook,similar to a shelterregister, to record yourthoughts and achievement ofWeb page showing geocache near <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong>the find. The cache is thenrehidden in the same spot forthe next treasure seeker.Letterboxers, on the otherhand, don’t leave trinkets tofind, but rather a unique rubberstamp that the successfulhunter uses to commemoratehis find by inking his personallogbook. In exchange, theyleave their custom stampmark in the provided log tovalidate their find.Geocaching emerged afterthe government brought anend to “selective availability,”a process by which the U.S.military regularly degradedthe signal from its satellitesthat the GPS units need toContinued on page 28A.T. exhibit opens in ShenandoahA new exhibit about the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> has opened in the Byrd Visitors Centerat Big Meadows in the ShenandoahNational Park. It fills an entire room andtraces the history and background of the<strong>Trail</strong>, highlighting the role volunteers haveplayed in turning it from one man’s dreamto a 2,168-mile reality.A cooperative project of the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> Conference and the NationalPark Service, it was developed by volunteersand staff from ATC, <strong>Trail</strong>-maintainingclubs, and the Park Service’s <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong> and Shenandoah NationalPark units. (ATC photo: Laurie Potteiger)APPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 17

Sharing the <strong>Trail</strong>As the A.T. becomes one of the lastgreen corridors linking the wildplaces of the East, humans aren’tthe only ones who follow itBy Christine WoodsideJust south of Vermont’s Killington Peak, the corridorof green around the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> skirts a largecomplex of ski lifts, a restaurant, a lookout tower,and wide ski trails. Thousands of hikers follow the <strong>Trail</strong>around the development every year.So do some bears.The idea seems odd at first: Why would wild animals,known to avoid humans, use trails marked with signsand white-paint blazes? Nevertheless, there are unmistakablesigns that part of central Vermont’s populationof black bears lumbers along the A.T. every year to getfrom spring shoots to berry bushes to nut trees.The bears were here first, scientists say, probably usinggame trails along the Coolidge Range long beforepeople named it, marked it, and mapped it. “We’re reallyMigration along the A.T.? Whitetaildeer populations maysupport traveling coyotes; blackbears may follow the corridor forshort distances. Canada geese,red-shouldered hawks, and othermigratory birds fly along theridgelines. (ATC file photos)18 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

literally walking historic bear trails in many places,” saysMike Pelton, a scientist at the University of Tennesseewho specializes in bears. The bears rely on this region forfood from early spring through the fall. At about 3,300feet, between Little Killington and Shrewsbury Peak, biologistshave seen claw marks on tree trunks in a largestand of beeches. They have found bear droppings andmatted-down areas where they rest, and they believe thebears walk on the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> to get from place toplace.An enduring and mostly incorrectThe corridor’s larger purpose over the next half-century,Peterson suggests, will be to maintain a connectionfrom one national forest or national park to another. Freepassage over large areas allows mammals to stake outterritories far from where they were born, giving themaccess to critical food sources and making the breedingpool more diverse and therefore healthier.Is the notion of trails offering a lifeline to isolated communitiesof wild animals just wishful thinking? Theanswer isn’t clear. Don Owen, environmental-protectionspecialist for the National Parklegend about the A.T. is “I personally don’t think it serves as Service’s A.T. office, says thethat it follows early nativemuch of a migration route for terrestrialanimals. Of course, when you’re<strong>Trail</strong> corridor probably is tooAmerican trails, which in turnnarrow in most areas to providewalking northbound on the <strong>Trail</strong> infollowed animal paths. But,regular routes for large mammals.Maine and meet a southbound moose,what about the reverse? As theyou could easily argue otherwise.”<strong>Trail</strong> and <strong>Trail</strong> corridor become“The A.T. corridor is pretty—Don Owenthe only links between woodlandareas, are animals beginningto rely on it?Biologists in western Massachusettsbelieve certain bearscould use the <strong>Trail</strong> there at timesbecause their home ranges overlapthe <strong>Trail</strong>. In ShenandoahNational Park, a healthy populationof coyotes appears to bepreying upon deer along the <strong>Trail</strong>corridor, the park’s newsletterreported in 1999. The <strong>Trail</strong> corridormay be help safeguardthose animals’ futures, because it connects public parksand forests to each other.The buffer lands make a biological highway, says KevinPeterson, until recently the regional administrator for theATC Land Trust in the northern states and a former regionalrepresentative for ATC. As the East becomes moredeveloped, the <strong>Trail</strong> corridor is more than an escape forpeople. As roads and buildings fragment bear ranges—and squeeze travel routes of moose, deer, and possiblycoyote—<strong>Trail</strong> lands provide a crucial protected habitatfor some animals.narrow, it’s broken periodicallyby roads and other linear intrusions,and it’s hemmed in bydevelopment in many locations.As a result, I personallydon’t think it serves as much ofa migration route for terrestrialanimals,” Owen says. “Ofcourse, when you’re walkingnorthbound on the <strong>Trail</strong> inMaine and meet a southboundmoose, you could easily argueotherwise.”In Vermont, near Killington,there is evidence the <strong>Trail</strong> is providing that connection.“The A.T. corridor serves as one of two principal travelcorridors between a big block of national forest land northof Route 4 and a bigger block south of Route 140,”Peterson says.Another example of the <strong>Trail</strong> corridor’s ability to provideconnective habitat can be found in the story of thetimber rattlesnake in Connecticut. Once so numerousthat thirty towns in Connecticut were named after it,this snake now is on the state’s list of endangered species.People no longer kill rattlers on sight, as they did asAPPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 19

ecently as thirty years ago, but the snakes are hemmedin by roads in many places where they used to live. Theytry to travel for several miles at various times of the year.Few areas other than the <strong>Trail</strong> corridor allow them thiskind of room.While biologists can only guess if the <strong>Trail</strong> is a bywayalong its entire length, the bears’ use of the <strong>Trail</strong> nearKillington in Vermont becamewell documented between 1987and 1997. The ski companyhoped to use about 3,000 acresit owned south of KillingtonPeak to dig a pond forsnowmaking. Other planscalled for more ski lifts, trails,and condominiums. Scientistsfor the Vermont state government,those hired by the skicompany, and an environmentalgroup that formed to fightthe development visited a largestand of beech trees very closeto the proposed pond. On onefield trip a decade ago, theyfound more than fifty treesmarked with fresh claw marksthat proved a healthy numberof black bears were climbing upfor the nuts each fall.This stand is between a quarter-and a half-mile from the<strong>Trail</strong>. Eventually, the state offered to swap state forestlandnorth of Killington for the area south of the peak,where the bears seem to roam. The deal was struck in1997 and became final in December 1998. The womanwho started a citizens’ group to fight the proposed skidevelopment believes the <strong>Trail</strong> is a part of the bears’ route.“Bears will use the <strong>Trail</strong>, for sure,” says Nancy Bell, aformer teacher from Shrewsbury, Vermont, who led themovement to save the bear habitat. Ms. Bell often hashiked in that area, both on and off the <strong>Trail</strong>, seeing evidenceof the animals. “Moose use the <strong>Trail</strong> also,” sheadds. “They go high up in winter.”“The ridgelines of the Blue RidgeMountains and Kittatinny Mountainsare key features of the migratory flywayfor raptors and many other speciesof birds. Now, because of the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong>, those ridgelines areprotected forever.”—Don OwenFor several years, the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> Conference hasbeen working with biologists in every state through whichthe <strong>Trail</strong> passes to compile an inventory of plants—and,when time and funding allow, animals—along the <strong>Trail</strong>corridor. The state governments’ natural-heritage divisionsof their environmental-protection departmentsusually conduct the studies. Those lists help the <strong>Trail</strong>groups protect endangered andthreatened plants and animalswhere possible, even to the extentof relocating the <strong>Trail</strong>around them if necessary, saysKent Schwarzkopf, a natural-resourcespecialist with the NPS<strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> office inHarpers Ferry.The inventories show the<strong>Trail</strong> is an important conservationzone for numerous unusualspecies, Schwarzkopf says.“We’re surveying, not just forthreatened and endangered species,but for any rare species orrare-plant community that ispresent along the <strong>Trail</strong>. In theten years in which we’ve beenconducting rare-species searchesalong the A.T., hundreds of locationshave been identified.This emphasis on rare-speciesidentification and protectionhas meant that other research, including the <strong>Trail</strong>’s potentialto serve as a migration route, has not taken place.”Birds, though, probably benefit most from the uninterruptedtree canopy on the ridgelines the <strong>Trail</strong> follows,Owen says. For example, he says, “the ridgelines of theBlue Ridge Mountains and Kittatinny Mountains are keyfeatures of the migratory flyway for raptors and manyother species of birds. Now, because of the <strong>Appalachian</strong><strong>Trail</strong>, those ridgelines are protected forever.”Christine Woodside is a Connecticut-based writer andreporter who thru-hiked the <strong>Appalachian</strong> <strong>Trail</strong> in 1987.20 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>

Hiker bread for beginnersBy Fred FirmanWhen I shared campsites with “Mr. Zooman,” who I metwhen I was hiking part of the A.T. in 1997, each night hewould cook a savory meal prepared and dehydrated byhis wife at home. Meanwhile, I would be stirring a small can oftuna or chicken into yet another pot of Lipton Noodles ’n Sauce.My meals weren’t bad, but the fragrant smells and exclamationsof satisfaction coming from his vicinity made it clearwhose were better.That experience opened a door for me. I bought an inexpensivedehydrator and began drying spaghetti sauce and chili, andDRY INGREDIENTSApricot/Almond Hiking BreadMakes 24 pieces; 206 calories and 5.5 grams proteinper piece.2 cups whole wheat flour2 cups all purpose flour1 cup soy flour1.5 cups chopped driedapricots1 cup sliced almonds1/2 tsp salt1/2 tsp Nu SaltWET INGREDIENTS2 large eggs1/2 cup canola oil1/2 cup honey2 cups milk (low fat)1 tsp vanilla extractGinger Hiking BreadMakes 24 pieces; 220 calories and 5.33 grams proteinper piece.Fred and Joanne Firman (and their dog Poppy) serving up a freshpan of “Ginger Hiking Bread.” (Photo: Dorlyn Williams)DRY INGREDIENTS2 cups whole wheat flour1cup corn meal1 cup soy flour1 cup rye flour2/3 cup raisins2/3 cup chopped walnuts1/2 cup brown sugar2 tsp ginger2 tsp ground cinnamon1/2 tsp ground nutmeg1/2 tsp ground cloves1 /2 tsp table salt1/2 tsp Nu SaltWET INGREDIENTS2 large eggs1/2 cup canola oil1 cup dark molasses2 cups milk (low fat)I started looking more closely at other food options, such aslogan bread. If you’re tired of the same old hiking food, youmight want to consider trying it.Logan bread, if you’ve never had it, is a dense, calorie-packedbread that keeps well on the <strong>Trail</strong>. According to a 1997 BackpackerMagazine article on trail breads, a key point is to drythe breads out; removing moisture is what makes them last.The dehydrator made that simple. After reading June Fleming’sThe Well-Fed Backpacker, which offers general nutritional principlesand encourages readers to try their own recipes, Ideveloped a few that my wife, Joanne, and I like enough to takeon hikes, vacations, and just plain day trips. Although Joanneis usually the cook in our home, enough people have asked forthe recipes that I thought I’d write them down.Like logan bread, they are dense, for easy packing and storagein the refrigerator. When dried, they will keep for monthsAPPALACHIAN TRAILWAY NEWS 21

in a fridge or weeks in a maildrop or pack. They are high inprotein and contain a mix of simple carbohydrates, complexcarbohydrates, and fats that the body burns at different ratesfor even, sustained energy. Here’s what you need to make alarge batch:Equipment• 5.5 qt. mixing bowl• 1.5 qt. or larger mixing bowl• Large (11” x 17” x 1”) cookie /jelly-roll pan;a second pan can be used for separating the baked breadsquares if you dry the bread in your oven.• Whisk (a fork will do).• Stirring spoon (sturdy)• Measuring cup and spoonMeasurementsBeginners (like me) may find some hints about measuring useful:Heap all dry ingredients a bit above the rim of their measuringcup or spoon, then level off the top using some handystraight edge. Measure brown sugar by packing it into the measuringcup firmly enough that, when dumped out, the sugarwill retain the shape of the cup. Measure flour by first stirringto loosen it up in its storage container, then spooning it intothe measuring cup (the standard dip-and-swipe method yieldsabout ten percent more flour, which makes the batter thickerand requires more liquid than the spoon-and-level method).IngredientsAll-purpose flour—Your basic, everyday, white wheat flour willdo. Note that wheat varieties vary in “hardness”; “hard” wheathas more protein and absorbs more liquid than “soft” wheat,which is more common in the U.S. south (hard wheat is morecommon in the U.S. north and Canada). These recipes werecreated using King Arthur flour, a very hard wheat milled inVermont. If your batter seems too runny or your bread turnsout crumbly, ask your grocer about a harder flour.Soy flour—All these recipes contain a cup of soy flour. Soyhas about twice the protein of other grains, and it’s a completeprotein. In most of the recipes, it is limited to one cup becausemore than that starts to hurt the texture and flavor. Some groceriescarry this flour, but you will be more likely to find it athealth-food stores.Nu Salt—This is a brand-name salt substitute. It is almostentirely potassium chloride, and, when I am on the <strong>Trail</strong> for awhile, I start craving foods that are naturally high in potassium.Potassium is an electrolyte that our bodies need, and I’ve noticedthat the sports drinks and sports bars all have it. Now, Ihike better in the heat and haven’t developed the cravings.Canola oil—I want fat for its concentrated energy, and I usecanola oil because it is the cooking oil with the least saturated(read artery-clogging) fat.Poppy Seed/Orange Hiking BreadMakes 24 pieces; 285 calories and 7 grams proteinper piece.DRY INGREDIENTS2 cups whole wheat flour2 cups all purpose flour1 cup soy flour1 tbsp orange peel1/2 tsp table salt1/2 tsp Nu SaltDRY INGREDIENTSWET INGREDIENTS2 large eggs2 cans poppy seed filling6 oz. can frozenorange juice1/2 cup canola oil1/2 cup honey2 cups milk (low fat)Tahini/Lemon Hiking BreadMakes 24 pieces; 185 calories and 7.8 gramsprotein per pieceNote: This bread has a decidedly different tastethat some have described as “tastes like it mustbe good for you.” I eat it sparingly for the changein taste and for the high calorie and protein content.It takes some patience to get the tahini andthe other wet ingredients to mix.2 cups whole wheat flour2 cups all purpose flour1 cup soy flour1/2 tsp table salt1/2 tsp Nu SaltWET INGREDIENTS3 large eggs1 lemon—zest and juice1 8 oz. can tahini1/2 cup canola oil1.5 cups honey1.5 cups milk (low fat)1 tsp vanilla extractMilk (low fat)—I’m trying to reduce the saturated fats in mydiet, but regular milk should work just as well.Almond paste—Marzipan is more readily available, but differsfrom almond paste in the proportion of sugar to groundalmonds. I’ve tried to adjust the almond-paste recipe usingmarzipan and compensating for this confection’s additionalsweetening, but I haven’t liked the results.Poppy-seed filling—Your grocery may carry it in a specialtyfood section or only carry it in the fall around Rosh Hashanah.22 JULY–AUGUST <strong>2001</strong>