Woodberry Forest School

Woodberry Forest School

Woodberry Forest School

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

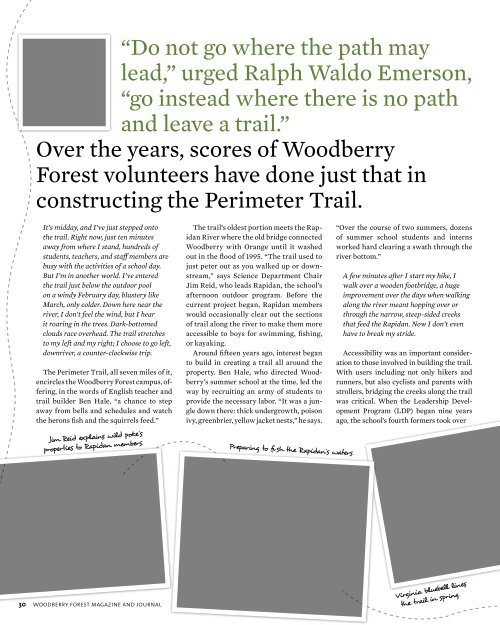

“Do not go where the path maylead,” urged Ralph Waldo Emerson,“go instead where there is no pathand leave a trail.”Over the years, scores of <strong>Woodberry</strong><strong>Forest</strong> volunteers have done just that inconstructing the Perimeter Trail.It’s midday, and I’ve just stepped ontothe trail. Right now, just ten minutesaway from where I stand, hundreds ofstudents, teachers, and staff members arebusy with the activities of a school day.But I’m in another world. I’ve enteredthe trail just below the outdoor poolon a windy February day, blustery likeMarch, only colder. Down here near theriver, I don’t feel the wind, but I hearit roaring in the trees. Dark-bottomedclouds race overhead. The trail stretchesto my left and my right; I choose to go left,downriver, a counter-clockwise trip.The Perimeter Trail, all seven miles of it,encircles the <strong>Woodberry</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> campus, offering,in the words of English teacher andtrail builder Ben Hale, “a chance to stepaway from bells and schedules and watchthe herons fish and the squirrels feed.”Jim Reid explains wild poke’sproperties to Rapidan members.The trail’s oldest portion meets the RapidanRiver where the old bridge connected<strong>Woodberry</strong> with Orange until it washedout in the flood of 1995. “The trail used tojust peter out as you walked up or downstream,”says Science Department ChairJim Reid, who leads Rapidan, the school’safternoon outdoor program. Before thecurrent project began, Rapidan memberswould occasionally clear out the sectionsof trail along the river to make them moreaccessible to boys for swimming, fishing,or kayaking.Around fifteen years ago, interest beganto build in creating a trail all around theproperty. Ben Hale, who directed <strong>Woodberry</strong>’ssummer school at the time, led theway by recruiting an army of students toprovide the necessary labor. “It was a jungledown there: thick undergrowth, poisonivy, greenbrier, yellow jacket nests,” he says.Preparing to fish the Rapidan’s waters.“Over the course of two summers, dozensof summer school students and internsworked hard clearing a swath through theriver bottom.”A few minutes after I start my hike, Iwalk over a wooden footbridge, a hugeimprovement over the days when walkingalong the river meant hopping over orthrough the narrow, steep-sided creeksthat feed the Rapidan. Now I don’t evenhave to break my stride.Accessibility was an important considerationto those involved in building the trail.With users including not only hikers andrunners, but also cyclists and parents withstrollers, bridging the creeks along the trailwas critical. When the Leadership DevelopmentProgram (LDP) began nine yearsago, the school’s fourth formers took overwhere the summer school students left off,building bridges and stiles, clearing trash,and installing erosion control structures.All eight of the trail’s bridges and some ofthe fence crossings were constructed as EagleScout projects or by LDP crews. “Withthe design help of our grounds and maintenancefolks, the sophomores have built somehandsome and sturdy bridges,” says DebCaughron ’74, who directs <strong>Woodberry</strong>’s outdoorprograms. “This spring, one crew willbe installing stairs to make a steep area moreaccessible and less susceptible to erosion.”When I round a bend, I see movement outof the corner of my eye. I stop to watch agreat blue heron lift its long body off theriver on giant wings and flap silently away,legs dangling beneath it.To walk along the trail is to be immersedin nature. An abundance of wildflowersblankets the forest floor in spring, whilecountless types of trees — including sycamore,hackberry, maple, and river birch —shade the path in the summer. According to<strong>Woodberry</strong> English teacher and birder PeterCashwell, “The trail is a great place forbirding because it incorporates a variety ofhabitats.” In his book The Verb ‘To Bird,’ Peterlists sixty-seven species of birds that hespotted in his yard when he lived near theportion of the trail along the Rapidan. Thebirds range from woodpeckers and songbirdsto Canada geese and bald eagles.Abundant food sustains the birds, deer,foxes, and other wildlife for whom the forestis home. In late summer, blackberry busheslean over the trail, sagging with ripe fruit.Sassafras leafLast fall, Jim Reid took students foragingon the trail for an atypical <strong>Woodberry</strong> meal:sassafras tea, pawpaw bread, roasted chestnuts,hickory nuts, and mushrooms, washeddown with freshly pressed pear cider froman ancient tree.I’m just about to leave the part of the trailfronting the river and head up into thewind, so I decide to take a break at one ofthe forts. This one is elaborately fitted outwith a shelter built from found materialsand decorated with flags, banners, thewhitened skull of a cow, and old licenseplates. I pull up a camp chair, have a drink,and watch the river.River forts have become a campus tradition.Each of the dozen forts, built over theyears by the boys, represents an opportunityfor them to escape the daily routine and enjoy<strong>Woodberry</strong>’s natural surroundings. The boysare responsible for registering and maintainingthe forts, and the Student River Committeedocuments each fort on a map displayedin Anderson Hall. Begun by Anson Howard’06 in his sixth-form year, the committeemonitors the cleanliness of the forts and hashelped shape the rules for use of the river.Ford Schwing ’09, who heads the committee,explains that “our job is to preserve the delicateecological balance of the river and to helpthe community enjoy the river while keepingit clean and healthy.” But stewardshipdoesn’t mean restricting activities. “Keepingtrash out of the river allows for the best fishingpossible,” says Ford, “and establishing ahabitat area will give the community a placeto learn about the diverse plants and wildlifeLDP members build a bridgein 2008 with guidancefrom Keith Johnson (center).that thrive here.” The committee’s next projectis to install wood duck boxes in one of theprotected habitat areas to encourage nestingof the crested waterfowl.Now that I’ve left the woods, I squeezethrough a stile and head over openpasture, looking out for the white-tippedposts that mark the trail. I pass througha field of heifers and calves. They eye mesuspiciously, letting out the occasionalwarning moo. I try to act casual and nonthreatening,especially after Brad Douthit,<strong>Woodberry</strong>’s farm manager, drives byin his truck and warns me about heifernumber ninety-one. Once I’ve crossedthe fence, I take out my trail map for thefirst time. From here I can see the centralcampus. I’m wondering if I’m at the trail’shigh point, so I check the map. I figure I’mhalfway around the loop.According to English teacher RichardBarnhardt ’66, the driving forces behind thecreation of the Perimeter Trail have beenBen Hale and Doug David, father of Haynes’05 and Grainger ’96. “Doug got us focusedon what the design of the trail should be,”says Richard, “and Ben was our man on theground.” Doug saw the trail’s potential on avisit to Haynes’s fort. Having developed theAnderson Creek Retreat in Georgia, a communitythat preserves the natural environmentwhile providing community spaces foroutdoor pursuits, Doug knew how to makesubstantive plans for the trail. “He had experiencemapping the kind of trail we wanted,”Richard says. Doug brought in JohnExley, a planner who had beenVirginia bluebell linesthe trail in spring.A glimpse of a white-tailed doe.30 woodberry forest magazine and journal fall 2008 / winter 2009 31