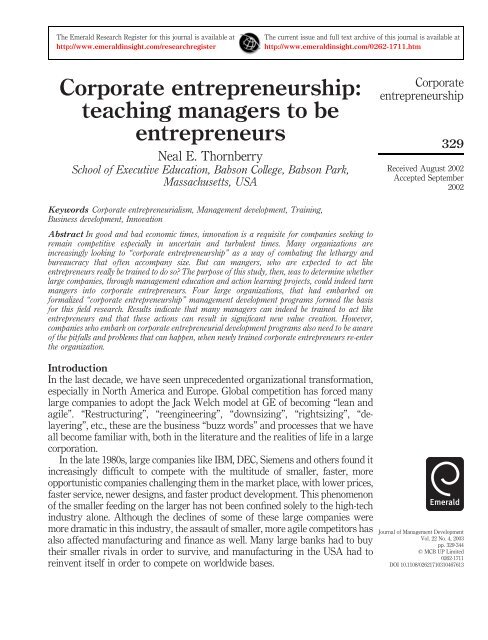

Corporate entrepreneurship: teaching managers to be entrepreneurs

Corporate entrepreneurship: teaching managers to be entrepreneurs

Corporate entrepreneurship: teaching managers to be entrepreneurs

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

an opportunity that his competi<strong>to</strong>rs have missed? Thus the idea of corporate<strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> has a certain cache that is hard <strong>to</strong> resist.But what is the reality? Can corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> really <strong>be</strong> instilledin<strong>to</strong> a bureaucratic culture? How different are corporate <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> fromexternal <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>, and how well does the entrepreneurial mindset fitwithin a hierarchical corporate structure? There are few empirical answers <strong>to</strong>these questions. The literature abounds with examples, but unfortunately theexamples often revolve around a few high profile examples like 3M, andDisney. These companies have had long his<strong>to</strong>ries of innovation andopportunity focus as cultural values, and have had numerous processes thatinstitutionalized these values (Greco, 1999; Roepke et al., 2000; Schrage, 1999).There is relatively little field research regarding the successes or failures oflarge companies who have tried <strong>to</strong> systematically instill corporate<strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> within their walls.The purpose of this paper, then, is <strong>to</strong> discuss the results and lessons learnedfrom field research involving the attempt <strong>to</strong> create internal or corporate<strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> within four large companies –Siemens-Nixdorf, Colonia-AxaInsurance, the Venezuelan Oil Company (PDVSA), and Mott’s (a part ofCadbury Schweppes) – struggling <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> more innovative. Two of theseorganizations favored a corporate venturing approach, while the other twofollowed more of an intrapreneuring approach.<strong>Corporate</strong><strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>333Background<strong>Corporate</strong> venturingBoth Siemens-Nixdorf Information Systems Company (SNI) and Mott’sfollowed a corporate venturing path.SNI came <strong>to</strong> Babson College in 1995 with an RFP <strong>to</strong> create a managementeducation program for its unit <strong>managers</strong>. The main purpose of the programwas <strong>to</strong> create a group of 300 corporate <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> within SNI who wouldlearn <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> opportunity-focused, not just resource-focused. GerhardSchulmeyer, President of SNI, had embarked on an organization-wide changeprogram <strong>to</strong> turn a rather staid, conservative, risk-averse culture in<strong>to</strong> a moreopportunistic, market-focused, fast, flexible organization in order <strong>to</strong> competemore effectively with the likes of H-P, IBM, Arthur Anderson, and the smallaggressive boutique IT vendors increasingly present in the marketplace.Both SNI and Mott’s followed a corporate venturing path.Schulmeyer had already brought in new board mem<strong>be</strong>rs from the outside,and was involved in a num<strong>be</strong>r of internal change efforts when Babson Collegewas approached <strong>to</strong> design and deliver the corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> program.The entrepreneurial development program was considered a corners<strong>to</strong>ne inSNI’s change efforts <strong>be</strong>cause it was meant <strong>to</strong> make corporate <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> ou<strong>to</strong>f <strong>managers</strong> who had just <strong>be</strong>en assigned <strong>to</strong> the newly-created position of unitmanager. The unit manager’s job sat at the intersection <strong>be</strong>tween the the line of

JMD22,4336(2) Is it <strong>be</strong>tter <strong>to</strong> try and identify people within the company who alreadyhave entrepreneurial leanings, or can any competent, motivated managerlearn <strong>to</strong> act and think like an entrepreneur?(3) Is corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> really an oxymoron? Can people actually<strong>be</strong> trained and then allowed <strong>to</strong> act like start-up <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> within analready, well-established company. Or, as stated <strong>be</strong>fore, are there <strong>to</strong>omany corporate antibodies in place <strong>to</strong> allow such a phenomenon?(4) If there are such antibodies at work, how do large companies learn <strong>to</strong>identify and overcome them?(5) Finally, is there a real return on investment in such educationalendeavors? Do any new, truly entrepreneurial ventures come <strong>to</strong> fruitionthat justify both the program’s expense and the <strong>managers</strong>’ time awayfrom other potentially more productive and certain activities? Ultimately,will increased entrepreneurial <strong>be</strong>havior actually lead <strong>to</strong> the capturing ofhigher margin, durable new business opportunities by the company?Summary of findingsFor purposes of confidentiality, the author has chosen <strong>to</strong> consolidate thegeneral findings from these four companies. Several sources of data served as afoundation for the following results. First, many of these programs haverequired that participants develop full-blown business plans and then competewith others in front of an executive team for resources and support. Thus, thereis some hard data regarding business plans that have actually developed in<strong>to</strong>successful businesses. We also have feedback from senior management, HRrepresentatives and the participants themselves as <strong>to</strong> how much they actuallylearned and could apply within their own businesses. While there are somecompany specific differences in results, the degree of similarity in the findingswas impressive.Nature v nurturePerhaps the first question is the most critical one for companies considering<strong>teaching</strong> <strong>managers</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>. We now <strong>be</strong>lieve, <strong>be</strong>yond any doubt,that much of what start-up <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> do can <strong>be</strong> taught <strong>to</strong> relativelyordinary but motivated individuals. So what do start-up <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> knowand do that can potentially <strong>be</strong> learned by others?Start-up <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> do three things very well. They identifyopportunities, shape and develop these opportunities, and then they create abusiness structure <strong>to</strong> turn these opportunities in<strong>to</strong> successful businessventures. The starting point is an idea that is new. This new idea could <strong>be</strong>revolutionary or evolutionary and it might not even <strong>be</strong> theirs, but there issomething different about it. Start-up <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> then <strong>be</strong>gin <strong>to</strong> learn aboutthis idea <strong>to</strong> see if is just an idea or an opportunity. They change it, shape it,modify, and sometimes discard it for something <strong>be</strong>tter. Once they are satisfied

that their idea has commercial merit, they <strong>be</strong>gin <strong>to</strong> build an organization ofpeople and resources <strong>to</strong> go about capturing the opportunity.Identifying and shaping ideas can <strong>be</strong> learned. We have many great examplesof <strong>managers</strong> who never considered themselves creative or innovative, whofound significant new business opportunities as a result of their entrepreneurialtraining. A Siemens manager, for example, found a unique way <strong>to</strong> s<strong>to</strong>p creditcard fraud through fingerprinting technology. A PDVSA team identified ahuge commercial market for one of their waste products that they used <strong>to</strong>throw away. A Mott’s employee identified a way <strong>to</strong> start a spin-off business,based on Mott’s back-office competencies. None of these opportunities wouldhave <strong>be</strong>en discovered had these participants not <strong>be</strong>en exposed <strong>to</strong> a trainingmilieu, in which ideas were not only encouraged and supported but challengedas well. So, the ability <strong>to</strong> think creatively and <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> innovative is a humancondition. Some people exhibit these tendencies naturally while others need acatalyst for these inherent capabilities <strong>to</strong> emerge. Education and particularlycoaching turned out <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> two of the most important ways in which innovationand creativity were stimulated <strong>to</strong> emerge. What the <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> trainingdid most effectively, was give participants the <strong>to</strong>ols, techniques, and discipline<strong>to</strong> distinguish <strong>be</strong>tween a good idea and a good opportunity.Clearly, the most “teachable” aspect of the opportunity process is thebusiness plan. Business plans have both clear structure and clear contentrequirements. In fact, the business plan was perhaps our most important<strong>teaching</strong> <strong>to</strong>ol. All the theory, case studies, and group discussions could notreplace the tremendous amount of learning that went on when participants wererequired <strong>to</strong> turn their idea in<strong>to</strong> a full-blown business plan. The written businessplan is one of the few ways that we could determine whether the participant’sidea was just that, an idea, or a commercial opportunity. Every participant whocompleted a business plan said it was the most important (and perhaps one ofthe most painful) learning experience about <strong>be</strong>ing an entrepreneur that they hadever had. Managers who have gone through the development of a completedbusiness plan are not the same when they finish. They have had <strong>to</strong> learn aboutmarketing, finance, value, cash flow projections, etc., <strong>to</strong> a point where they canstand in front of their peers, senior <strong>managers</strong> or venture capitalists and convincethem that their opportunity is worth investing in.It was also interesting that many of the program participants said theyeither knew how <strong>to</strong> write a business plan or had already written one prior <strong>to</strong>coming <strong>to</strong> the program. It was clear from our experience that very few of thesepeople actually had business planning skills that would pass muster in front ofa venture capitalist or an internal venture officer.<strong>Corporate</strong><strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>337Identifying people with the “right stuff”One of our most surprising results, and one that we had not predicted, was thatwe were not able <strong>to</strong> predict with any reasonable certainty which <strong>managers</strong>

JMD22,4338would emerge as the most entrepreneurial. Neither background, education, orpast successes were good predic<strong>to</strong>rs of corporate entrepreneur success. Twoexamples will make this abundantly clear. One of our first entrepreneurialtraining program participants was a 50 year-old engineer with no prior his<strong>to</strong>ryof innovation or entrepreneurial orientation in his work his<strong>to</strong>ry. He was a good“hands on” engineer, quiet and “anal-retentive” in personality, and was forced<strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> in the program by his boss; clearly not the <strong>be</strong>st of candidates from aneducational training perspective. We all wrote him off at the <strong>be</strong>ginning of thecourse as a never-<strong>to</strong>-<strong>be</strong> corporate entrepreneur. However, he <strong>be</strong>came one of aminority of participants who actually came up with a great idea, shaped it in<strong>to</strong>a viable opportunity and wound up running a successful spin-off business forthe corporation. In his own words, he got “switched on”. He was clearly nothappy <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> on the course at the outset, but fell in love with a very innovativeidea he and another participant had cooked up, and then he <strong>be</strong>cameuns<strong>to</strong>ppable in his pursuit of this idea. He claimed that the training programgave him the courage and confidence <strong>to</strong> try his hand as a corporateentrepreneur. The more he learned, the more he was coached, and the more wedemystified the entrepreneurial process, the more confidence he gained.The second example involved one participant who was an exceptionallyhigh achiever in the company with impeccable MBA credentials from anextremely prestigious business school. We all predicted that he would outentrepreneureveryone in the class. Unfortunately, he could never come <strong>to</strong> gripswith leaving the security of his functional position. He demanded that thecompany guarantee his salary, bonuses, and position, no matter whathappened if he pursued his venture idea. He wanted no downside for <strong>be</strong>ing acorporate entrepreneur, only an upside; clearly, not the kind of stuff that<strong>entrepreneurs</strong> are made of. In this company, potential <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> wereencouraged <strong>to</strong> drop the course if it <strong>be</strong>came obvious <strong>to</strong> us or <strong>to</strong> them that theywere not cut out for this role. He was one of the first <strong>to</strong> drop the course forwhich he had so eagerly volunteered.<strong>Corporate</strong> antibodiesOur experiences with these four companies attempting <strong>to</strong> inculcate<strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> demonstrated the importance of company culture and <strong>to</strong>plevelleadership as extremely important ingredients for developing <strong>managers</strong>as <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>. All of the aforementioned companies embarked on theirvarious journeys in<strong>to</strong> corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> with the sincere <strong>be</strong>lief thatthey were committed <strong>to</strong> this goal and ready <strong>to</strong> support it. But only two out ofthe four were able <strong>to</strong> go the distance in terms of full support for those whoseideas had merit. The other two s<strong>to</strong>pped short of their goals for a num<strong>be</strong>r ofreasons, but four key barriers or challenges s<strong>to</strong>od out.(1) If an organization is <strong>to</strong> teach <strong>managers</strong> <strong>to</strong> act like <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>, theymust also <strong>be</strong> willing <strong>to</strong> pay them as <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>. Two of our sample

companies were either unwilling or unable <strong>to</strong> change their pay structuresin order <strong>to</strong> support corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>. Pay structures in largecompanies are often quite structured and systematic and therefore easy<strong>to</strong> administer but equally hard <strong>to</strong> change. They are often geared <strong>to</strong>equity and fairness, not the creation of internal <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>. Personnelpeople have often spent extraordinary amounts of time fine-tuning thesepay programs <strong>to</strong> ensure both external and internal equity. However, fewif any, of these pay systems are capable of dealing with an internalentrepreneur. It is not the purpose in this article <strong>to</strong> discussentrepreneurial pay schemes but they involve current payment on thepromise of future success, and they often involve some equity stake bythe internal entrepreneur in the future venture. For these reasons alonesome companies prefer <strong>to</strong> spin out the venture so that it will not <strong>be</strong>constrained by the company’s often fair but constraining policies,especially those of pay.(2) A second barrier involved time. In all four of our companies,<strong>managers</strong> were expected <strong>to</strong> do their day jobs and develop anopportunity <strong>to</strong> the point where it would either <strong>be</strong> funded or killed. Onthe surface, this approach makes sense from a “vetting” point of view.If you don’t really love your idea and see it as a real opportunity, thenyou won’t have the motivation <strong>to</strong> do your day job and work on a newventure at the same time. Start-up <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> also often work for alarge company, and in their spare time pursue their dream of startingtheir own business. Unfortunately, for most of our company “would<strong>be</strong>”<strong>entrepreneurs</strong>, their day jobs were almost overwhelming. All thedownsizing and increased pressure for short term quarterly resultshad pushed many of the <strong>managers</strong> with whom we worked in<strong>to</strong> tenand 12 hour days. So there was precious little time or energy left <strong>to</strong>pursue another opportunity especially if the rewards were not clear fordoing so.(3) A third and quite surprising obstacle that we discovered from our workwith these companies involved the peers of the program participants. Itwas surprising how many of these manager’s peers hoped they failed intheir efforts <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong>come corporate <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>. Because thisphenomenon (no head shall rise above the rest, unless it’s mine)existed across all four of our companies – we have <strong>be</strong>en led <strong>to</strong> concludethat this may <strong>be</strong> a human condition in many companies. Competition forjobs, promotions, etc., undoubtedly causes many of us <strong>to</strong> judge our worthin terms of others’ successes. In large bureaucratic organizations whereit is difficult <strong>to</strong> differentiate oneself or <strong>to</strong> stand out, the prospect of seeingsomeone else chosen as a corporate entrepreneur with the potential <strong>to</strong>run their own businesses and get rewarded accordingly, can createintense jealousy. Many of our would-<strong>be</strong> <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> found this change<strong>Corporate</strong><strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>339

JMD22,4340in their peer’s <strong>be</strong>havior difficult <strong>to</strong> cope with. We uncovered severalinstances of peers going <strong>to</strong> their joint boss <strong>to</strong> complain that theentrepreneur was not holding up his/her part of the workload andtherefore should <strong>be</strong> taken out of the entrepreneurial training program.The bosses on the other hand had not seen this supposed downturn inproductivity.(4) The fourth and biggest obstacle was the corporate entrepreneur’s directline boss. In all four of our companies, senior management wascommitted <strong>to</strong> trying <strong>to</strong> create greater innovation and new businessdevelopment through the development of corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>.Unfortunately, many of the bosses a level or two down from these seniorexecutives were not so committed. We had numerous reports of directline bosses telling their <strong>managers</strong> in our program <strong>to</strong> “forget what youwere taught, all I care about is meeting our quarterly results”. It often<strong>to</strong>ok strong executive team intervention <strong>to</strong> dissuade these direct bossesfrom acting in this manner. Obviously many of these direct bosses wereeither poorly informed about what the company was trying <strong>to</strong> do, or theyhad not bought in<strong>to</strong> the processes for obvious and often legitimatereasons.Does corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> really make a difference?First, let’s look at what success means. One end of the continuum would <strong>be</strong> achange in the manager’s <strong>be</strong>havior, which fosters more innovation, creativeproblem solving, and circumvention of red tape. The manager is not really acorporate entrepreneur in terms of creating a new business venture, but he orshe is now much more appreciative of the importance of new ideas, and thenacts <strong>to</strong> create a more innovative culture for his/her employees. We have createdan experimental Entrepreneurial Orientation Survey, which we hope will allowus <strong>to</strong> assess this type of change in <strong>be</strong>havior from a pre/post programperspective. As previously stated, there is some fairly strong evidence thatacting more entrepreneurially as a manager can have a significant impact onboth attitudinal and financial measures, even if the manager does not create anew business (Pearce et al., 1997).At the other end of the spectrum is the creation of a completely newbusiness, which is durable and generates a great deal of money for theorganization, much like the returns venture capitalists seek.But, at the end of the day, the real test of a corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>training is whether significant new businesses or new business results fromthis type of educational immersion. As one might expect, we have severalspectacular successes and many failures. But, perhaps our sample ofstatistics from these four companies is no different than what would <strong>be</strong>expected from looking at the num<strong>be</strong>r of successful ventures funded byventure capitalists.

First, a couple of the spectacular successes:(1) One of our <strong>managers</strong>-turned-entrepreneur proposed a new business thatwould focus on oil company distribu<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> help them manage both frontand back end logistics <strong>be</strong>tter. In addition, his new business was one ofthe first <strong>to</strong> create the “speed pass” idea that allows mo<strong>to</strong>rists <strong>to</strong> wave amicrochip in front of the gas pump as a method of payment. Within thefirst three years of his new company’s creation, it was grossing over 250million dollars in revenues.(2) Another example involved an entrepreneurial team whose innovativeidea of turning waste oil products in<strong>to</strong> a new business for xxxx resultedin yyyy revenues.Clearly, these examples are impressive and they happened in companies wherethe overall cultures were not particularly entrepreneurial, thus dispelling thenotion that cultural change has <strong>to</strong> happen <strong>be</strong>fore the fruits of entrepreneurialinterventions can <strong>be</strong> realized. But, they must also <strong>be</strong> seen in the light of theoverall approach <strong>to</strong> training <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>. Over the past six years we haveprobably run corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> programs for well over 1,000 <strong>managers</strong>.While many of these <strong>managers</strong> descri<strong>be</strong> the educational process and thedevelopment of a business plan as the most significant business educationexperience they have ever had, relatively few, perhaps 10-15 percent of theseentrepreneurial plans ever led <strong>to</strong> successful new ventures. Again, this data seems<strong>to</strong> square with the notion that most (90 percent) new start-up businesses fail.The deck seems <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> stacked equally against corporate <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> aswell as start-up entrpreneurs. On the other hand, the venturing process doesresult in the generation of many new ideas, the education of people regardingdifferences <strong>be</strong>tween good ideas and good opportunities, and many times newcorporate knowledge and competencies which did not exist <strong>be</strong>fore. Ourexample of the thumb-printed credit card created new technologicalcompetencies that have <strong>be</strong>en leveraged elsewhere within the company. It isunlikely that this technology would have <strong>be</strong>en commercialized had Siemens notempowered this manager <strong>to</strong> think and act in a more entrepreneurial manner.Lessons learned.Pockets or islands of entrepreneurial activity can develop and thrive, atleast for a while, in cultures that are not in themselves entrepreneurial.Clearly, researchers are right when they claim that organizational cultureplays a key role in a company’s ability <strong>to</strong> develop corporate<strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> (Morris, 1998; Hood and Young 1993; Bygrave, 1997).But, successful ventures can develop in non-entrepreneurial companieswith the right kind of tactical interventions. This is good news forcompanies who are <strong>to</strong>ld that it takes five <strong>to</strong> eight years <strong>to</strong> change culture.Perhaps, it only takes a critical mass of switched-on corporate<strong>Corporate</strong><strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>341

JMD22,4342<strong>entrepreneurs</strong>, with some championing at the senior level, <strong>to</strong> start <strong>to</strong> seeresults..A lot of ordinary corporate citizens can learn <strong>to</strong> act as corporate<strong>entrepreneurs</strong> with the right education, training, and support. The mostcritical piece is that they are helped <strong>to</strong> develop an idea that theythemselves are turned on <strong>to</strong>. Without this passion, it would <strong>be</strong> hard <strong>to</strong>imagine anyone willing <strong>to</strong> fight the uphill battle that many of our would<strong>be</strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong> had <strong>to</strong> do. This really speaks <strong>to</strong> the mindset of theentrepreneur. Passion can’t <strong>be</strong> taught, but it can <strong>be</strong> encouraged. The skillset, however is much easier <strong>to</strong> teach. Market analyses, cash flow analysis,operations management etc., can <strong>be</strong> taught, as we know from workingwith MBAs and other executives..Catalytic coaching and the business planning process were the two mostimportant educational <strong>to</strong>ols for the development of new businessopportunities. Catalytic coaching sounds like an oxymoron, but itinvolved pushing <strong>managers</strong> <strong>to</strong> move from an iterative focus <strong>to</strong> a platformfocus. Most <strong>managers</strong>, when asked <strong>to</strong> think about new businessopportunities, tend <strong>to</strong> start close <strong>to</strong> home with iterative, relatively smallchanges <strong>to</strong> products or services. It takes a push from a coach whoaggressively challenges this “close <strong>to</strong> home” mentality typically found inthe ideation phase. We saw many mediocre ideas blossom in<strong>to</strong> trulyentrepreneurial ideas as a result of this type of coaching. In addition, thisis where some of the real passion developed within the corporateentrepreneur. They started <strong>to</strong> fall in love with their ideas, especially whenthey <strong>be</strong>came really interesting and more risky. Many of Mott’s peoplestarted off with ideas about packaging and apple sauce color. At the endof the program they were thinking about day care centers and managingbrands for the World Wide Wrestling Federation, a far cry from blueapple sauce. These types of ideas are more of a platform of ideas in thatthey leverage the corporation’s capabilities, but in<strong>to</strong> significantlydifferent product offerings or markets. The importance of the businessplan is obvious. Great ideas without the discipline of the businessplanning process are generally not great opportunities. This was the mostimportant <strong>to</strong>ol for differentiating the two and further shaping theopportunity. One of our <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> came <strong>to</strong> us in a pertur<strong>be</strong>d state<strong>be</strong>cause his business plan was telling him that he could not make anymoney with his original idea. He was afraid that he would some how “fail”the entrepreneurial course. We soundly congratulated him for notspending the company’s money on a bad idea and <strong>to</strong>ld him <strong>to</strong> find anotherone. This little s<strong>to</strong>ry says a lot. Being entrepreneurial also means knowingwhen <strong>to</strong> “pull the plug”..Entrepreneurs can come from anywhere in the organization. One of ourbiggest lessons was our inability <strong>to</strong> predict who could <strong>be</strong>come a corporate

entrepreneur. When experience, creativity <strong>to</strong>ols, coaching, and a person’sown confidence and desire collide with market knowledge, cus<strong>to</strong>merintimacy information, and technological changes, entrepreneurialopportunities are identified. We could not predict with any accuracywho would <strong>be</strong> in the intersection at the right time, but providing thisintersection in a planned way did result in brand new businesses andsignificant innovation in current businesses. In addition, we could notpredict which of our would-<strong>be</strong> <strong>entrepreneurs</strong> would <strong>be</strong> motivated. OurMBA star arrived motivated, <strong>be</strong>came unmotivated and then quit. Ourolder engineer arrived unmotivated, got excited and stayed. So theinteresting research question is, what are the key ingredients for causingthe right kinds of collisions at the intersection. We know some of theelements but not others..Decoupling ideation and opportunity identification from implementation.As we looked at our four companies, we discovered that some individualsreally do have the right stuff <strong>to</strong> identify, develop, and implement a newbusiness venture from start <strong>to</strong> finish. They are akin <strong>to</strong> many start-up<strong>entrepreneurs</strong>. We also encountered people who were good at the creativeopportunity identification and shaping phases, but who could not or didnot want <strong>to</strong> implement their idea. For them, the fun was in theconceptualization piece, not the implementation piece. Thus, anycorporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> process must first <strong>be</strong> framed around thequestion of whether a company wants <strong>to</strong> develop corporate<strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> processes or corporate <strong>entrepreneurs</strong>. The processapproach means that a company does not expect the same people <strong>to</strong>develop and then implement a new business, but they want the structuresand processes in place, which help <strong>to</strong> identify, shape, and then capture anew business opportunity. Many companies are starting <strong>to</strong> build oralready have, some form of entrepreneur process in place. Intel, Proc<strong>to</strong>r &Gamble, Ford, Dow and others are exploring and testing these variousmachines of innovation. Obviously not all of these structures work(Altman, 2000) but companies seeking greater innovation are increasinglyexploring new avenues. An emphasis on identifying and supporting a“corporate entrepreneur” who is expected <strong>to</strong> follow a new opportunityfrom start <strong>to</strong> finish is a relatively new model and one that does not requirethe same investment in fixed assets. We do know that passion counts andinstitutionalized processes do not always take this in<strong>to</strong> account. Perhapscompanies seeking innovation need <strong>to</strong> pursue both paths..The last lesson is that a little difference can make a big difference. Notevery manager needs <strong>be</strong> an entrepreneur <strong>to</strong> help a company spawnsignificant new business opportunities. Several of our examples,particularly the $250 million dollar one, attest <strong>to</strong> this. So companiesneed <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> realistic about how much corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> is<strong>Corporate</strong><strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>343

JMD22,4344enough. Do companies really need <strong>to</strong> change their culture, or get a coupleof big wins every few years? Perhaps many organizational consultantshave put <strong>to</strong>o much effort in<strong>to</strong> organizational change as a pre-requisite <strong>to</strong>venturing. May<strong>be</strong> more emphasis on venturing first, and a few wins,would do more <strong>to</strong> change the culture than the other way around.ReferencesAltman, J. (2000), “Xerox new enterprises” (case study), Arthur M. Blank Center forEntrepreneurship, Babson College, Wellesley, MA.Block, Z. and MacMillan, C. (1993), <strong>Corporate</strong> Venturing, Harvard Business School Press, Bos<strong>to</strong>n,MA.Bygrave, W (Ed.) (1997), The Portable MBA in Entrepreneurship, Wiley, New York, NY.Covin, J. and Slevin, D.P. (1991), “A conceptual model of <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> as firm <strong>be</strong>havior”,Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 15, pp. 7-24.Covin, J.G. and Miles, M.P. (1999), “<strong>Corporate</strong> <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong> and the pursuit of competitiveadvantage”, Entrepreneuship Theory and Practice, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 47-63.Greco, J. (1999), “Strategists of the century: Walt Disney”, Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 20No. 5, pp. 33-4.Hood, J. and Young, E. (1993), “Entrepreneurship’s requisite areas of development: a survey of<strong>to</strong>p executives in entrepreneurial firms”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 8 No. 2,pp. 115-36.Morris, M. (1998), Entrepreneurial Intensity, Quorum Books, London.Pearce, J.A., Kramer, T.R. and Robbins, D.K. (1997), “Effects of <strong>managers</strong>’ entrepreneurial<strong>be</strong>haviour on subordinates”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 147-60.Pinchot, G. III (1985), Intrapreneuring, Harper & Row, New York, NY.Roepke, R., Agarwal, R. and Ferratt, T.W. (2000), “Aligning the IT human resource with businessvision: the leadership imperative”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 327-53.Schrage, M.D. (1999), “Serious play: how the world’s <strong>be</strong>st companies stimulate innovation”,Research Technology Management., Vol. 42 No. 6, p. 58.Schumpeter, J.A. (1934), The Theory of Economic Development, Harvard University Press,Bos<strong>to</strong>n, MA.S<strong>to</strong>pford, J. and Baden-Fuller, C.W. (1993), “<strong>Corporate</strong> <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>”, in Lorange, P.,Chakravarthy, B., Roos, J. and Van de Ven, A. (Eds), Implementing Strategic Processes:Change, Learning and Cooperation, Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 91-114.S<strong>to</strong>pford, J.M. and Baden-Fuller, C.W. (1994), “Creating corporate <strong><strong>entrepreneurs</strong>hip</strong>”, StrategicManagement Journal, Vol. 15, pp. 521-53.Timmons, J. (1989), The Entrepreneurial Mind, Brick-House Publishing Company, Andover, MA.