Who pre-drinks before a night out and why? - Alcohol Action Ireland

Who pre-drinks before a night out and why? - Alcohol Action Ireland

Who pre-drinks before a night out and why? - Alcohol Action Ireland

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

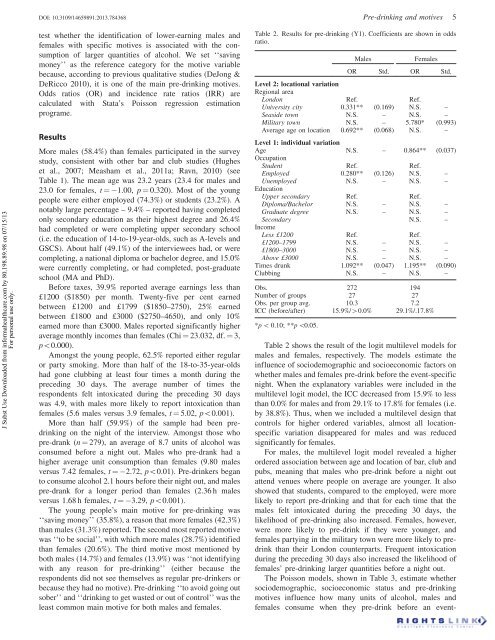

DOI: 10.3109/14659891.2013.784368 Pre-drinking <strong>and</strong> motives 5J Subst Use Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by 80.198.89.98 on 07/15/13For personal use only.test whether the identification of lower-earning males <strong>and</strong>females with specific motives is associated with the consumptionof larger quantities of alcohol. We set ‘‘savingmoney’’ as the reference category for the motive variablebecause, according to <strong>pre</strong>vious qualitative studies (DeJong &DeRicco 2010), it is one of the main <strong>pre</strong>-drinking motives.Odds ratios (OR) <strong>and</strong> incidence rate ratios (IRR) arecalculated with Stata’s Poisson regression estimationprograme.ResultsMore males (58.4%) than females participated in the surveystudy, consistent with other bar <strong>and</strong> club studies (Hugheset al., 2007; Measham et al., 2011a; Ravn, 2010) (seeTable 1). The mean age was 23.2 years (23.4 for males <strong>and</strong>23.0 for females, t ¼ 1.00, p ¼ 0.320). Most of the youngpeople were either employed (74.3%) or students (23.2%). Anotably large percentage – 9.4% – reported having completedonly secondary education as their highest degree <strong>and</strong> 26.4%had completed or were completing upper secondary school(i.e. the education of 14-to-19-year-olds, such as A-levels <strong>and</strong>GSCS). Ab<strong>out</strong> half (49.1%) of the interviewees had, or werecompleting, a national diploma or bachelor degree, <strong>and</strong> 15.0%were currently completing, or had completed, post-graduateschool (MA <strong>and</strong> PhD).Before taxes, 39.9% reported average earnings less than£1200 ($1850) per month. Twenty-five per cent earnedbetween £1200 <strong>and</strong> £1799 ($1850–2750), 25% earnedbetween £1800 <strong>and</strong> £3000 ($2750–4650), <strong>and</strong> only 10%earned more than £3000. Males reported significantly higheraverage monthly incomes than females (Chi ¼ 23.032, df. ¼ 3,p50.000).Amongst the young people, 62.5% reported either regularor party smoking. More than half of the 18-to-35-year-oldshad gone clubbing at least four times a month during the<strong>pre</strong>ceding 30 days. The average number of times therespondents felt intoxicated during the <strong>pre</strong>ceding 30 dayswas 4.9, with males more likely to report intoxication thanfemales (5.6 males versus 3.9 females, t ¼ 5.02, p50.001).More than half (59.9%) of the sample had been <strong>pre</strong>drinkingon the <strong>night</strong> of the interview. Amongst those who<strong>pre</strong>-drank (n ¼ 279), an average of 8.7 units of alcohol wasconsumed <strong>before</strong> a <strong>night</strong> <strong>out</strong>. Males who <strong>pre</strong>-drank had ahigher average unit consumption than females (9.80 malesversus 7.42 females, t ¼ 2.72, p50.01). Pre-drinkers beganto consume alcohol 2.1 hours <strong>before</strong> their <strong>night</strong> <strong>out</strong>, <strong>and</strong> males<strong>pre</strong>-drank for a longer period than females (2.36 h malesversus 1.68 h females, t ¼ 3.29, p50.001).The young people’s main motive for <strong>pre</strong>-drinking was‘‘saving money’’ (35.8%), a reason that more females (42.3%)than males (31.3%) reported. The second most reported motivewas ‘‘to be social’’, with which more males (28.7%) identifiedthan females (20.6%). The third motive most mentioned byboth males (14.7%) <strong>and</strong> females (13.9%) was ‘‘not identifyingwith any reason for <strong>pre</strong>-drinking’’ (either because therespondents did not see themselves as regular <strong>pre</strong>-drinkers orbecause they had no motive). Pre-drinking ‘‘to avoid going <strong>out</strong>sober’’ <strong>and</strong> ‘‘drinking to get wasted or <strong>out</strong> of control’’ was theleast common main motive for both males <strong>and</strong> females.Table 2. Results for <strong>pre</strong>-drinking (Y1). Coefficients are shown in oddsratio.MalesFemalesOR Std. OR Std.Level 2: locational variationRegional areaLondon Ref. Ref.University city 0.331** (0.169) N.S. –Seaside town N.S. – N.S. –Military town N.S. – 5.780* (0.993)Average age on location 0.692** (0.068) N.S. –Level 1: individual variationAge N.S. – 0.864** (0.037)OccupationStudent Ref. Ref.Employed 0.280** (0.126) N.S. –Unemployed N.S. – N.S. –EducationUpper secondary Ref. Ref.Diploma/Bachelor N.S. – N.S. –Graduate degree N.S. – N.S. –Secondary N.S. –IncomeLess £1200 Ref. Ref.£1200–1799 N.S. – N.S. –£1800–3000 N.S. – N.S. –Above £3000 N.S. – N.S. –Times drunk 1.092** (0.047) 1.195** (0.090)Clubbing N.S. – N.S. –Obs. 272 194Number of groups 27 27Obs. per group avg. 10.3 7.2ICC (<strong>before</strong>/after) 15.9%/40.0% 29.1%/.17.8%*p 5 0.10; **p 50.05.Table 2 shows the result of the logit multilevel models formales <strong>and</strong> females, respectively. The models estimate theinfluence of sociodemographic <strong>and</strong> socioeconomic factors onwhether males <strong>and</strong> females <strong>pre</strong>-drink <strong>before</strong> the event-specific<strong>night</strong>. When the explanatory variables were included in themultilevel logit model, the ICC decreased from 15.9% to lessthan 0.0% for males <strong>and</strong> from 29.1% to 17.8% for females (i.e.by 38.8%). Thus, when we included a multilevel design thatcontrols for higher ordered variables, almost all locationspecificvariation disappeared for males <strong>and</strong> was reducedsignificantly for females.For males, the multilevel logit model revealed a higherordered association between age <strong>and</strong> location of bar, club <strong>and</strong>pubs, meaning that males who <strong>pre</strong>-drink <strong>before</strong> a <strong>night</strong> <strong>out</strong>attend venues where people on average are younger. It alsoshowed that students, compared to the employed, were morelikely to report <strong>pre</strong>-drinking <strong>and</strong> that for each time that themales felt intoxicated during the <strong>pre</strong>ceding 30 days, thelikelihood of <strong>pre</strong>-drinking also increased. Females, however,were more likely to <strong>pre</strong>-drink if they were younger, <strong>and</strong>females partying in the military town were more likely to <strong>pre</strong>drinkthan their London counterparts. Frequent intoxicationduring the <strong>pre</strong>ceding 30 days also increased the likelihood offemales’ <strong>pre</strong>-drinking larger quantities <strong>before</strong> a <strong>night</strong> <strong>out</strong>.The Poisson models, shown in Table 3, estimate whethersociodemographic, socioeconomic status <strong>and</strong> <strong>pre</strong>-drinkingmotives influence how many units of alcohol, males <strong>and</strong>females consume when they <strong>pre</strong>-drink <strong>before</strong> an event-