Hinduism Today January 2009 - Cover, Index, Front Articles

Hinduism Today January 2009 - Cover, Index, Front Articles

Hinduism Today January 2009 - Cover, Index, Front Articles

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

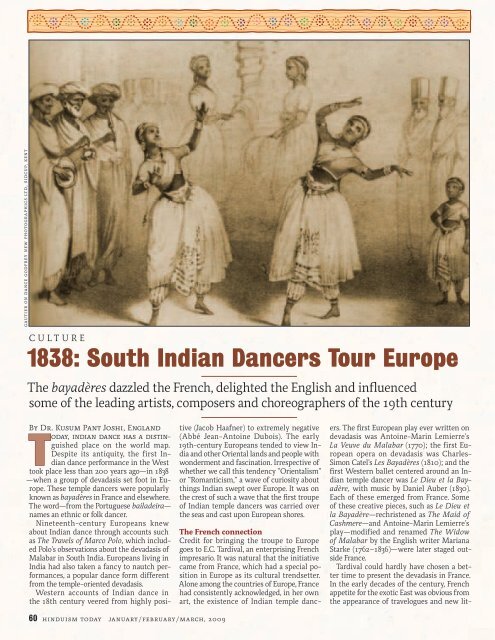

The Continent: (left) The Indian troupewas a hit in France, where their talentswere better showcased than in England.ers. The first European play ever written ondevadasis was Antoine-Marin Lemierre’sLa Veuve du Malabar (1770); the first Europeanopera on devadasis was Charles-Simon Catel’s Les Bayadères (1810); and thefirst Western ballet centered around an Indiantemple dancer was Le Dieu et la Bayadère,with music by Daniel Auber (1830).Each of these emerged from France. Someof these creative pieces, such as Le Dieu etla Bayadère—rechristened as The Maid ofCashmere—and Antoine-Marin Lemierre’splay—modified and renamed The Widowof Malabar by the English writer MarianaStarke (1762–1836)—were later staged outsideFrance.Tardival could hardly have chosen a bettertime to present the devadasis in France.In the early decades of the century, Frenchappetite for the exotic East was obvious fromthe appearance of travelogues and new litgautieron dance godfrey new photographics ltd, sidcup, kentCulture1838: South Indian Dancers Tour EuropeThe bayadères dazzled the French, delighted the English and influencedsome of the leading artists, composers and choreographers of the 19th centuryBy Dr. Kusum Pant Joshi, England<strong>Today</strong>, indian dance has a distinguishedplace on the world map.Despite its antiquity, the first Indiandance performance in the Westtook place less than 200 years ago—in 1838—when a group of devadasis set foot in Europe.These temple dancers were popularlyknown as bayadères in France and elsewhere.The word—from the Portuguese bailadeira—names an ethnic or folk dancer.Nineteenth-century Europeans knewabout Indian dance through accounts suchas The Travels of Marco Polo, which includedPolo’s observations about the devadasis ofMalabar in South India. Europeans living inIndia had also taken a fancy to nautch performances,a popular dance form differentfrom the temple-oriented devadasis.Western accounts of Indian dance inthe 18th century veered from highly positive(Jacob Haafner) to extremely negative(Abbé Jean-Antoine Dubois). The early19th-century Europeans tended to view Indiaand other Oriental lands and people withwonderment and fascination. Irrespective ofwhether we call this tendency “Orientalism”or “Romanticism,” a wave of curiosity aboutthings Indian swept over Europe. It was onthe crest of such a wave that the first troupeof Indian temple dancers was carried overthe seas and cast upon European shores.The French connectionCredit for bringing the troupe to Europegoes to E.C. Tardival, an enterprising Frenchimpresario. It was natural that the initiativecame from France, which had a special positionin Europe as its cultural trendsetter.Alone among the countries of Europe, Francehad consistently acknowledged, in her ownart, the existence of Indian temple danc-erature, as well the first French translationof Kalidasa’s Abhigyan Shakuntalam, entitledLa reconnaissance de Sacountala. Thiswas written in 1820 by Antoine-Léonard deChézy, the first European Professor of Sanskrit.With public curiosity further rousedby exposure to Western versions of devadasison the French stage, the time was clearlyripe for the real artists to be showcased beforethe French public.Tardival took care to ensure the success ofhis program. Near the French base of Pondicherryin South India, he found a group ofauthentic devadasis linked to the Perumaltemple of Thiruvanthipuram. He commissionedthem for 18 months. The troupe offive female dancers and three male musiciansconsisted of Tille Ammal, a womanof about 30, and four female dancers underher charge: Amany, 18, Saoundiroun andRamgoun, both about 14, and Veydoun, justsix years old. In contemporary sketches, Veydoun,who appears dressed in clothes identicalto the older dancers, looks like a miniversion of the others. She was aptly and affectionatelydescribed by a French theatercritic: “Imagine Cupid dyed in black. Veydounis the most charming, mischievous andthe brightest little devil.”Records indicate that Tardival offered thetroupe an excellent pay package, agreeing togive each dancer Rs. 10 per day (a generoussum in those days), plus an additional 1,000rupees—half at the outset of their engagementand the remainder when they returnedto India.“A sensation of dazzling light...”Ammal and her troupe arrived in France onJuly 24, 1838. At Bordeaux, their first port ofcall, they watched a performance of the ballet,Le Dieu et la Bayadère. Even as membersof the audience, the devadasis “excitedthe greatest attention,” according to reports.A week later, they gave their first performance,a private one. Soon they arrived inParis, where they were greeted with lengthyarticles in the French media. The excitementaugured well for the success of Tardival’sambitious program.The Parisian response was vividly reflectedby the city’s prominent theater critic, TheophileGautier. Regarding the prevailing mood,he wrote: “The very word bayadère evokesnotions of sunshine, perfume and beautyeven to the most prosaic and bourgeois mind.Imaginations are stirred, and dreams takeshape. There is a sensation of dazzling light,and through the pale smoke of burning incenseappear the unfamiliar silhouettes ofthe East. Until now bayadères had remainedclassical composersbibliothèque de l’opera, parisa poetic mystery like the houris of Muhammad’sparadise. They were remote, splendid,fairylike, fascinating. This scented poetrythat—like all poetry—existed only in ourdreams, has now been brought to us.” Afterwatching them perform in their residence inParis, Gautier wrote that they were, “charming,unimpeachably authentic and exactlycoincided with the idea we had formed ofthem.”Rumors that they were imposters vanishedafter a command performance beforeFrance’s King Louis Philippe on August 19,where they were showered with gifts fromthe royal family. Now publicity surroundingthe devadasis was so great that there weresome real attempts to kidnap them. Tardivallodged them in a secluded but verdantspot by the river Seine in a special bungalowprotected by a green shuttered fence with asoldier to guard the entrance. Being a dancetheatrical lonodonCritic’s choice: (above) Theater an derWien where the devadasis performed; (left)Influential theater critic Theophile Gautiergreatly contributed to their popularity; TheTheater Royal Adelphi in Londoncritic, Gautier was permitted into the houseand was accorded the privilege of watchingthe devadasis and their male musicians performat close quarters.Gautier wrote detailed descriptions of thedancers, particularly an extremely positiveaccount of the grace, beauty and charm ofAmany. From these reports and other sources,including a statuette of Amany craftedby French sculptor Auguste Barre, we canascertain that the devadasis were adornedin traditional jewelry, including nose rings,bangles, waist belts, ankle bells and silver toerings.A distinct picture of the three male musiciansof the troupe also emerges from Gautier’sreviews and is fully corroborated bycontemporary sketches. The grey-beardeddance master (nattuvanar) and senior-mostmember of the troupe, Ramalinga Mudali,conducted the devadasis as he sang, chanted60 hinduism today january/february/march, <strong>2009</strong> january/february/march, <strong>2009</strong> hinduism today 61