Briefing Note Pakistan Land Rights - Oxfam Blogs

Briefing Note Pakistan Land Rights - Oxfam Blogs

Briefing Note Pakistan Land Rights - Oxfam Blogs

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Academic Policy and Procedures Title: 04l Special Topics and Negotiated StudiesManual1.0 IntroductionThe following definitions and usage of Special Topic and Negotiated Studies courseshave been approved. The requirements for the course descriptors to be used forprogramme development that include Special Topics or Negotiated Studies coursesare attached as Appendices 1 and 2.These criteria are to be applied to all courses of this nature. Alternative titles for suchcourses should not be used and the use of a different title for a course would notprevent this policy from being applied to that course.2.0 Definitions and UsageThe course title ‘Special Topic’ is used when one-off topics/courses are to be deliveredto groups of students. The course descriptor of each special topic will be developed bythe Programme Committee and approved by the relevant Board of Studies. The topictitle will be entered in the programme’s Special Topic course on the StudentManagement System. The topic title will display on the student’s record and transcript.Special Topic courses will not be used for individualised study plans.For those courses in which individualised study plans are developed and approved, thecourse title “Negotiated Study” is used. These individual plans of study are approvedby the Programme Director and reported to the Programme Committee. ProgrammeCommittees may develop guidelines for approval.Special Topic and Negotiated Study courses will not be used to enrol students studyingcourses not listed in the regulations of the students programme. In these casesstudents are enrolled in the course they are studying as a Certificate of Proficiency(COP) and once completed the credits are credited to the student’s programme.©Unitec 2007 : Confidential to Unitec New Zealand Page 2 of 4

econstruction plans by providing both financial and technicalresources;;modify their own policies and programmes to focus more onthe landless and vulnerable rather than wealthy landowners;;support the government of <strong>Pakistan</strong> in computerizing landrecords.The UN should:ensure that post-disaster responses create more secure tenureand land rights for the poor and the marginalized in general,and women in particular;; to this end, to fully implement UN-HABITAT and UN-Food Agriculture Organisation (FAO )guidelines for rapid tenure security measures for returnees,protection and restoration of land rights of vulnerable groups,and secure rights and access to agricultural land for vulnerablegroups, including tenants and women;;support governments in conducting land needs assessmentswithin the first six weeks of any disaster;;develop programmes that safeguard landless women andmen against arbitrary land grabbing.<strong>Land</strong>lords should:show leadership in the recovery and reconstruction effort bywriting off the debts of small farmers;;play a constructive role as wealthy landowners and contributeto the rehabilitation of damaged and destroyed irrigationstructures so that landless and poor tenants can resumeagricultural activities quickly;;responsibly uphold tenancy rights under the Tenancy Act byallowing the re-entry of those who had been on their landbefore the floods (without embarking on exploitativerenegotiated terms) and to facilitate the swift reconstruction ofhomes on their properties.Civil society and the media should:play an active role in highlighting the issue of land inequalityand hold the government, the international donor community,and landlords accountable for adequately addressing landissues in recovery and reconstruction plans by monitoringprogress, holding public meetings, and ensuring thatmeaningful consultations are held with affected people;;5

6ensure NGO plans to tackle housing and shelter recovery andreconstruction take into account land inequality issues,especially the risk that poor people may face dispossessionfrom their homes where land rights are not assured.

GLOSSARY OF TERMSTenancy Act the Act governing the tenantlandlord relationship. Atenant is a person who holds land under another person and is liableto pay rent for the land. The tenant of a landlord operates under onelease or one set of conditions. The aim of this law is to accommodatelandless people and to provide cover and support them againstlandowners and landlords.Residential security secure ownership or tenant rights to land beingused for the purpose of housing/shelter;; also known as housingrights.<strong>Land</strong> security secure ownership or tenant rights to land being usedfor the purpose of housing/shelter or agricultural purposes.Collective entitlements collective historical rights to land that acommunity has been residing on for several years (usually decades orcenturies).Sharecropping is a system of agriculture whereby a landownerallows a tenant farmer to use the land in return for a share of the cropproduced on the land. riverine areas where property rights are poorlydefined. non-riverine area;; settled ar(embankment or dyke where people usually have permanent houses. is a proxy land title. It is most frequently used by malerelatives (husbands, fathers, sons, brothers) to assert effectiveownership of property which 7

1 IntroductionWe have no land of our own and are dependent on the goodwill of landlordsfor work and building our house. We are not allowed to reoccupy ourdamaged houses or plots even after the water had receded weeks ago. Thelandlord has levelled our damaged houses for the next wheat crop.A group of landless tenants in flood-affected areas of the Jafferabaddistrict, Balochistan.Lack of land ownership and inequitable access to land is a major causeof rural poverty in <strong>Pakistan</strong>. Most people who live in the rural areasaffected by the 2010 floods are landless. For millions of the rural poor,owning land and having reliable access to land for cultivation andhousing is about survival. It is about having the foundation forbuilding a better standard of living. For the rural poor, land is crucialbecause it is both a source of livelihood and allows them access togovernment benefits and schemes, as well as to credit for agricultureand business. Secure ownership of land for residential purposes isonly possible with formal land ownership documents.The 2010-11 floods have been devastating for millions of landlesswomen and men destroying their homes and livelihoods andwreaking devastation that will take years, if not decades, to overcome.It will significantly MillenniumDevelopment Goals. The floods resulted in a death toll of 1,700 peopleand the displacement of an estimated 18 million people across<strong>Pakistan</strong>. 1 Official estimates of the economic loss range from $8.74billion to $10.85 billion. These figures include the estimated costs ofearly recovery for the provision of relief, rebuilding destroyedinfrastructure, and other economic losses to individuals, communities,firms and the government. 2The floods have had a massive impact on land and agriculture, whichhas hit the country hard both economically and socially. Millions ofpoor women and men, mostly small farmers, have lost their land andassets. In the aftermath of the devastation caused by the floods, theyhave been displaced to camps or other places. With nearly half of therural population landless before the floods, these displaced womenback to rehabilitate it as they are mostly dependent on their landlords.They are also worried that the floods have provided the powerfullandlords with an opportunity to take over the land of poor farmers,since land boundaries have washed away and land ownershipdocuments have been lost in the floods. Women are facing the bruntof this loss of land and livelihoods. They feel insecure because they donot have shelter and they have lost their means of livelihoods.Before the floods the government at different levels had taken somepositive initiatives to address land issues, such as the government ofSindh <strong>Land</strong> Distribution Programme. Prioritizing land issues in thepost-floods phase is urgently needed. The government of <strong>Pakistan</strong>8

needs to change the way it approaches land issues to ensurecomprehensive land rights for poor farmers, especially women, acrossrecovery and reconstruction plans, including the WB, ADB, as well asthe <strong>Pakistan</strong> , makes inadequate mention of landissues. There are no plans to conduct a comprehensive review of landissues and no clear strategy and programmes to address landinequality issues for the poor and landless women and men.Securing land rights is linked to poverty and inequality since it canreduce poverty at both the individual and household level, and boosteconomic growth at national level. A comprehensive recovery and including landownership, tenure, and residential security. Recovery andreconstruction plans that have a clear strategy and programmes forpromoting land equality for poor women and men will reducepoverty and suffering among the flood-affected population. Now isthe time to make sure that policies and programmes related to landdispensation and ownership target the most marginalized people suchas women and religious minoritiesThis paper explores the historical context of land issues in <strong>Pakistan</strong>,the condition of land rights, and security of tenure in flood-affectedareas, how the impact of the floods is magnifying the vulnerability ofland rights of the poor and socially marginalized, and providesanalysis of recovery and reconstruction plans. It also includesrecommendations for the government of <strong>Pakistan</strong>, the internationalcommunity, landlords, and civil society actors for addressing landinequality issues and reducing landlessness and poverty in thecountry.9

2 Background of land issuesin <strong>Pakistan</strong><strong>Land</strong>: means of livelihood<strong>Land</strong> is not only a source of livelihood for over three-fifths of the ruralpoor, is also a means of reducing inequality and poverty. Sixty perthe rural population depends on agriculture for subsistence.However, the land is owned and controlled by a few the land elitewho are usually influential because they will either be inparliamentary positions or successful businessmen. Not only do theyown more land but they also have access to and control over marketand economic opportunities in rural areas. Most landless farmers andlabourers working for these influential landlords end up as bondedlabourers. Women bear the brunt of this situation as they are deniedeconomic opportunities due to lack of land ownership.Zainab, a previously landless woman farmer living in district Thattawho received land under government of Sindh <strong>Land</strong> DistributionProgramme before the floods, says:The effort that we would put on our own lands is due to it beingmyself, that pleasure of working on my own land is something else. It is a blessing towork on our own lands and have our house on the land that belongsto us and there would be no hardships, no extra efforts and noDespite their involvement in agriculture, livestock management, andwaged domestic and household work, due to cultural and socialbarriers, women get lower returns for their labour, have non-existentaccess to markets, and have weak access, control, and ownership overkey assets such as land.Prevalence of land inequalityAbsence of land ownership or simply the lack of access to the use ofland by tenant farmers and landless farmers, especially women, isconsidered to be one of the major causes of rural poverty in <strong>Pakistan</strong>.<strong>Land</strong> inequality in <strong>Pakistan</strong> is huge: only half of all rural householdsown agricultural land, 3 while the top 2.5 per cent of householdsaccount for over 40 per cent of all land owned. 4 Numerous studieshave highlighted that districts with high land inequality have higherpoverty and deprivation than districts with low land inequality. 5Rural Sindh, southern Punjab, and the tribal areas in KhyberPakhtunkhwa (KPK) and Balochistan have the highest incidence ofland inequality as well as the highest rate of vulnerability, chronicpoverty, lack of influence in the market, and incidences of violenceagainst women. As shown in Table 1, 50.8 per cent of ruralhouseholds in the three provinces of Sindh, Punjab, and KPK are10

landless. Sindh the worst flood-affected province has one of thehighest rates of absolute landlessness (66.1 per cent) and the lowestshare of land ownership (33.1 per cent).Table 1: <strong>Land</strong> ownership distribution, 2000: Sindh, Punjab, andKhyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KPK)SINDH PUNJAB KPKPROPORTION OF RURALHOUSEHOLDS (per cent)ALLTHREELANDLESS 66.1 47.7 45.0 50.8UNDER 1.0 acre 0.5 6.4 14.8 6.91.0 TO UNDER 2.5 acres 6.8 14.1 19.0 13.62.5 TO UNDER 5.0 acres 7.1 11.5 9.8 10.35.0 TO UNDER 7.5 acres 5.5 7.4 4.7 6.57.5 TO UNDER 12.5 acres 6.0 6.2 3.4 5.612.5 TO UNDER 25.0 acres 4.0 4.1 1.6 3.625.0 TO UNDER 50.0 acres 1.8 1.8 1.0 1.650.0 TO UNDER 100.0acres 1.0 0.5 0.4 0.6100.0 TO UNDER 150.0acres 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1150.0 AND ABOVE acres 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1Source: Based on Census of Agriculture 2000 and 1998 Population Census.Vulnerable groupsHistorically, most of the people residing in flood-affected areas haveno legal ownership of land, and possession is the only indicator ofownership. The most vulnerable are those people living in the katcho(riverine) areas of Sindh and South Punjab. In these areas, the issue ofrecords of land ownership is an uncertain one, as cultivation is oftencarried out on land that has not been properly surveyed by therevenue department, which is responsible for maintaining landownership records. This population has no secure access to the landthat is not only the source of their livelihoods, but also the site of theirhomes. The poor and small farmers living in pukka (non-riverine)areas are relatively better off. Ownership rights of agricultural landare maintained on a regular basis and the farmers have records offormal titles of land ownership or are involved in formal tenancyarrangements. An important aspect to note is that most citizen-basedentitlements are linked to having a fixed abode or house, thereforethere is a direct link between lack of residential security and socialmarginalization. Hence, an important aspect of the early recovery andreconstruction process is to ensure the poor and vulnerable are notmarginalized and missed out.11

Box 1 The government ofSindh began its <strong>Land</strong>Distribution Programme in 2008.During its first phase, 41,517acres of land was distributedwith nearly 70 per cent ofbeneficiaries being women. Mostwomen surveyed in rural areasSubsequently, a second phasewas announced which onlytargeted landless women, and53,224 acres of land wasdistributed among 1,700 women.Shehnaz, a beneficiary of thisprogramme, has had her lifetransformed after receiving fouracres of land under thegovernment of Sindh <strong>Land</strong>Distribution Programme:social status and was thought ofto my husband. It makes mereally happy that now I have astatus and recognition of mycapabilities. It is only due to thisland that today that I have comeout, am walking around my landsWomen face numerous barriers in gaining and retaining legal landentitlements. Pakiwomen, who do 70 per cent of all farming work. However, ahousehold survey, published in 2005 by the International Centre forResearch on Women shows women own less than 3 per cent of theland, and that even when women do own land, they may not haveactual control over it (i.e. it is a benami or proxy title with real controlexercised by a male relative). This situation is exacerbated byand by the lack of supportive state structures and mechanisms forinstitutionalized exclusion and marginalization of women isperpetuated by the lack of adequate policies, plans, and resources forwomen attaining and retaining land on the part of the state and publicinstitutions. While research has consistently shown that for womensecure access to land is critical for achieving gender equality and is afundamental factor in ensuring food security, shelter, and space for 6 This is clearlylife and status in society for the better.Legislative theory vs realityTenancyDirect land ownership is not the only way in which the poor can haveaccess to agricultural land land can be accessed through tenancy and each province has its own Tenancy Act. 7 Despite the legislativeframework, poor farmers are often exploited due to poorimplementation of the Tenancy Act and existing lacunas in the law.Nevertheless, tenancy is a potential way for poor farmers to haveaccess to agricultural land and self-employment, and directlycontributes to reducing landlessness. For example in Sindh, two out ofwork on any land. That means only a quarter of rural landlesshouseholds are able to grow food to support themselves. Despite theneed for improvements in policy and practice, tenancy is an importantavenue for the landless to be able to access land. Tenancy provides ameans of registering the use of a plot of land with the local revenueboard, with the participation of the landlord. Such registrationprovides assured access to the land for the lease period. However,further work needs to be done to ensure that tenancy laws andimplementation take into account the power dynamics betweentenants and landowners, and give tenants the legal support they need.Lack of residential securityhe state is compelled to provide housing to all citizens who areArticle 38 (d), 1973 Constitution of the Islamic Republic of<strong>Pakistan</strong>.12

The right to adequate housing is explicitlconstitution. Moreover, it is deemed a basic human right, which isof Human <strong>Rights</strong> and has also been recognized by key human rightstreaties and conventions that followed it. This right applies inemergency situations, and it has been reiterated and further detailedby various other tools and instruments, including the GenevaConventions (Art 147, IV Geneva Convention and Art 14, AP11), theInternally Displaced Persons (IDP) Guiding Principles (Principle 18b),and the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Guidelines onHuman <strong>Rights</strong> in Natural Disasters (Section B2). Nevertheless,insecure housing arrangements exist in most areas of <strong>Pakistan</strong>,especially in katcho (village settlements) and rural areas. Thepoorest and most marginalized individuals and groups are usuallydenied ownership of residential land. In most rural areas the poor aredependent on the landlord to provide a small piece of land on whichto build their houses. This is usually an insecure arrangement mostly agreed verbally, this agreement will be honoured for as longthe landlord is happy with his tenants. If there is any conflict or aSecurity of resirelations with the wider society and polity. Access to most citizenbasedentitlements is linked to having a fixed abode and secureresidential land. For example, the Benazir Income SupportProgramme (BISP) requires a computerized national identity card(CNIC), which can only be issued if a citizen has a fixed abode orhome. Therefore, poor people who do not own any residential landare the most socially marginalized. 8Collective entitlementsThere icustomary claim to communal ownership of land among policymakers and government officials. The absence of the necessarylegislative framework to protect the rights of the poor has resulted inthe exploitation of socially marginalized and indigenouscommunities, as seen in their experiences of oil, gas, and mineralextraction. Poor landless people do not benefit directly from theextraction of resources or the development in their areas, in terms ofbuilding of schools, drinking water schemes, or employmentopportunities with the oil and gas companies. Additionally, there areno coherent national and provincial policies governing the use offorests, mineral, and marine resources, with the result that landlesspoor are exploited and do not get land entitlements or appropriatecompensation if they are displaced from their place of origin.<strong>Land</strong> grabs<strong>Land</strong> grabs occur in <strong>Pakistan</strong> in various forms. The most common onein rural areas involves influential landlords illegally occupying stateland or forcefully evicting small farmers from their land andoccupying it by using their power and patronage. In urban areas thisis seen in the form of the land mafia illegally occupying land through13

violence and coercion (especially common in Karachi). The military,considered one of the largest landlords in the country, is involved inland grabs in different parts of the country. The most prominentexample is the case of the Okara military farms (in the Punjabprovince) where farmers, whose families have tilled the land forcenturies, have been struggling for ownership for a decade now andwhere the tenants continue to be denied property rights and arepermanently at risk of eviction. 9 10 A more recent phenomenon in landgrabs in <strong>Pakistan</strong> is linked to the leasing of large tracts of land toforeign governments. There have been reports in the media in the pastfew years that the government of <strong>Pakistan</strong> has been negotiating withSaudi Arabia to lease 500,000 acres of farmland. 11 The Ministry ofInterior and Ministry of Food and Agriculture denied these reports;;however, the Lahore High Court Chief Justice Khawaja MuhammadSharif issued a court order that restrains the government from leasingor selling land to foreign countries, without prior notice being givento the court. 12 There has been no meaningful community consultationand political representation on the issue of leasing land to foreigngovernments, neither has comprehensive research been conductedthat assesses how corporate farming, compared to small-scalefarming, will impact on the majority of small farmers in the country.Largely failed reforms<strong>Pakistan</strong> has seen three major land reforms and various governmentland distribution programmes in the last six decades, the majority ofwhich have had limited impact on changing the status of the ruralpoor and their land ownership. Since the reforms were notimplemented properly, most land-holdings still remain in the handsof a few families. Formal land reforms were instituted in 1959, 1972,and 1977. The third set of land reforms were initiated in 1977 by theZulfiqar Ali Bhutto. It was proposed that land ownership ceilings bereduced to 100 acres of irrigated and 200 acres of unirrigated land.However, these land reforms could not be completed since they werethe military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq andsupported by the Shariat Court. 13 In a country like <strong>Pakistan</strong>, such aninterpretation leaves the issue of land reform stalled andunnecessarily subjected to opposition from religious parties andorganizations.The last three decades has seen sporadic efforts to tackle the issue ofland inequality. In the 1990s, the civilian governments of both BenazirBhutto (PPP) and Nawaz Sharif (<strong>Pakistan</strong> Muslim League (N))announced different programmes to distribute state land amonglandless farmers, but no formal land reforms were initiated. Duringthe military government of General Pervez Musharraf, land reformsand programmes remained completely absent from the political andpolicy agenda. The WB Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper, officiallyadopted in 2001 by the government of <strong>Pakistan</strong>, mentioned thedistribution of state land only, and did not highlight the prevailingland inequality in the country nor address the highly unequallandlordtenant power relations. Overall, land reforms havedistributed just 7 per cent of total farm area since 1959, and they have14

failed to meaningfully reduce the concentration of land ownershipcurrently in the hands of the wealthy. 14 Commentators describereform, as has happened in other East Asian states, as one of the. 15continues to be alarmingly low, in the recent years positive steps havebeen taken to increase land ownership among women. In 2008, thegovernment of Sindh announced a major programme of landdistribution of about 225,000 acres amon(peasant farmers) in the province. The first phase of the programmewas implemented in 17 districts of Sindh, and about 41,517 acres ofland was distributed among 2,845 poor women and 1,184 men.Subsequently, a second phase was announced which only targetedlandless women, and 53,224 acres of land was distributed among1,700 women. Just before the floods in 201011 a third phase todistribute 95,000 acres was announced. Despite implementationchallenges, the process has empowered 4,545 women in total, givingthem increased authority within their households and communities15

3 Impact of the floodsThe impact of the floods was seen all across <strong>Pakistan</strong>, but the natureof flooding varied from area to area. In most parts of the country theflood waters receded after a few weeks, except in northern Sindh andeastern Balochistan where water remained for several months,constituting a major health hazard and a huge obstacle to resumingeconomic activities. Other areas are slowly restarting some kind ofeconomic activity, though that is also hindered by the loss of assets,and damage to land, irrigation structures, roads, etc.Understanding the complexities surrounding land issues is extremelyimportant when designing recovery plans. It is important that keydecision-makers, both in government and the internationalcommunity (such as the WB, ADP, UN Development Programme) arefully aware of the needs of landless farmers and the challenges theyface in having secure access to or ownership of land. Only then will itbe possible to have recovery plans that adequately address the needsof the poorest people.<strong>Land</strong>less farmers and tenantsMost of the regions badly affected by the floods also happened to bethe areas where land ownership is known to be highly unequal. Theproportion of rural households which own land is low (in Sindh, twoout of three households are landless), and large land-holdings accountfor a high proportion of the total flood-affected areas. Those who weredisplaced by the floods and lost their assets and means of livelihoodconsisted disproportionately of landless tenants and labourers. Whileland and agrarian systems vary between provinces, power derivedfrom land ownership is a fact of life in nearly all of the affecteddistricts. As Table 2 highlights, agriculture is the primary occupationin most districts and in certain districts, such as Jafferabad inBalochistan, landless tenants comprise as much as nearly 60 per centof the farming population.Table 2: <strong>Land</strong> tenure pattern in flood-affected districtsDistrict <strong>Land</strong>ownersas proportionof ruralhouseholds -per centAgriculture(notincludinglabourers)asproportionof alloccupations- per cent ofadult malesLabourers(includingagriculturallabourers) asproportion ofalloccupations -per centadult males<strong>Land</strong>lesstenantsasproportion of allfarmers -per centDadu (Sindh) 28.1 48.2 25.4 16.5 15.9Larkana(Sindh)31.7 61.8 22.9 22.5 15.3Areaoperatedbytenantsasproportion of allarea -per cent16

Thatta(Sindh)Muzaffargarh(Punjab)Nowshehra(KPK)Jafferabad(Balochistan)24.2 62.3 22.2 3.9 4.754.3 39.2 38.4 6.3 16.539.3 19.5 33.9 3.3 13.528.8 67.7 19.1 58.6 47.7Year 2000 1998 1998 2000 2000Source: Agricultural Census 2000 and Population Census 1998Access to land, therefore, is closely correlated with social status andpolitical power. 16 It is the poor landless tenants and labourers whohave been hit hardest by the floods, and now face an uncertain future,with mounting debts and no immediate way to start earning themoney necessary to rebuild their lives. A recent survey conducted by<strong>Oxfam</strong> shows that 85 per cent of people are worried about incomepoverty and that for over 70 per cent of people, getting a job was oneof their top priorities.Degrees of land security among the flood-affectedThere are many degrees of land security among the flood-affectedpopulation. A family who is not from a socially marginalized group,who has access to government entitlements, and to patronage by thepolitically influential will enjoy stronger land security. The mostvulnerable people, those who lived in bonded conditions without anyform of land security, see the post-floods displacement as anopportunity to come out of the debt trap that is their repressivelandlord. For the purposes of this paper, we have focused on threebroad categories of land security: 17Level of landsecurity<strong>Land</strong>lesswithout secureresidentialentitlements<strong>Land</strong>less withresidentialentitlementsDescription of groupNeither own land, norenjoy secure rights ofpossession over theirhomesteads.Include tenants/labourers living onprivately owned landof their landlords;;socially marginalizedgroups.Have some degree ofsecure possession (atleast of theirhomesteads).Impact of floodsRendered homelesssince rights to residenceare linked to economicrelationship withlandlord, i.e. residentialland is usually anextension of access toagricultural land.Increase in prevalenceof bonded labour.More at risk of beingdispossessed byinfluential landlordssince land boundarieshave washed away,17

Vulnerable to politicaland economic demandsof the landowners.especially in northernSindh and southernPunjab.More vulnerable toincluding supportduring elections, andthe provision ofcustomary unpaidservice at particulartimes.SmallholdersOwning some form ofagricultural land(usually less than fiveacres).Inherited land fromfamily mostly men,women havinginheritedland/received as gift indowry, or werebeneficiaries of thegovernment of Sindh<strong>Land</strong> DistributionProgramme.More at risk of illegaloccupation andcoercion by influentiallandlords since landboundaries washedaway and land recordsdestroyed (at householdlevel).<strong>Land</strong> damaged andassets destroyed sothese small farmers donot have enoughresources to startfarming.Demarcation and titles<strong>Land</strong> boundaries of both housing and agricultural land were washedaway in the floods. This could result in potential conflict amongneighbours and relatives surrounding the demarcation of their landfor both housing and farming. In some cases, whole settlements havebeen flattened by the floods, leaving no signs to define the settlement,household plots, or farming areas. Hence, it is important that therevenue department (which is responsible for maintaining landrecords and conducting land surveys) proactively surveys the floodaffectedareas to establish land boundaries sooner rather than later toavoid conflicts among communities and villages. Sufficient capacityshould be provided to the district level offices to ensure timelyattention to such issues.There is no question that legal land titles are essential for secureownership and to enable access to government and privateentitlements. However, the absence of strong government regulationmeans that the poorest, especially women, are vulnerable to coercionand illegal occupation by landlords and other influential members ofthe community. A title is not always a guarantee of rights over land.There is strong anecdotal evidence to suggest that in the scramble toreclaim land after the floods, politically powerful individuals were18

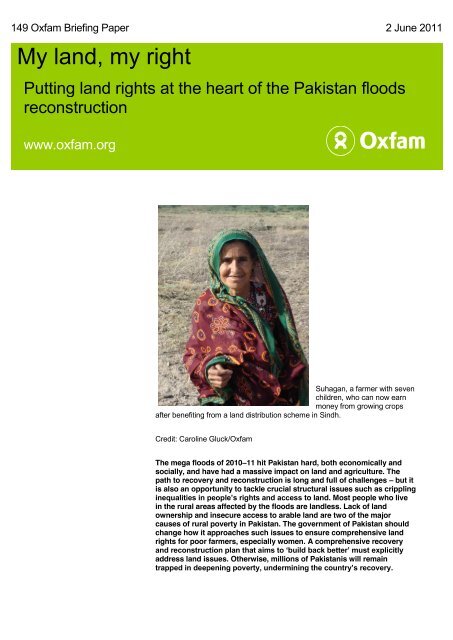

able to wield influence over land administration officials throughbribes and patronage, or harass the landowners to the point wherethey ceded their rights. 18 The people living in katcho areas of Sindhdepend heavily on their informal social networks and politicallyinfluential landlords for secure land possession.Box 2 The government ofSindh began its <strong>Land</strong>Distribution Programme in2008. Some of the womenland beneficiaries have hadappeal cases filed againstthem with 100 cases indistricts Thatta and Umerkot inSindh alone.in life would be so tough. I washeartbroken when a landlordfiled a case against my landapplication. Having no idea ofthe legal system I was initiallyso scared and decided not topursue the case since I had noidea of the law or courts. Butthrough encouragement andsupport of <strong>Oxfam</strong> and theirlocal partner, ParticipatoryDevelopment Initiatives (PDI), Idecided to fight my case andfeel proud of doing that andSuhagan, land beneficiary,district Thatta. Won her legalcase and now has legalownership of eight acres ofland where she can sow crops.This issue is not limited to the post-floods situation. During theof influential landlords filed legal appeals against the grant ofgovernment land to the poor women on the basis that the land wasnot government land, but their own private land. There is a provisionin land revenue laws that enables anyone to challenge thegrant of government land to any person. While it is important thatpeople are able to make such challenges, the system is currently beinggrossly abused. Even a handwritten note, without any good groundsfor appeal, can be submitted to the revenue department, and issufficient to lodge a formal appeal. As soon as the appeal is submitted,the allotment process is halted until resolved by a revenueadministrator or court. At times this can take months, even years,during which the women landowners are unable to move onto orcultivate their new property. Unfortunately, this law is being usedlargely by influential people against the poor women land grantees inSindh province, hence the large number of appeal cases against thesewomen land grantees (see Box 2). There have been nearly 100 caseslodged in the districts of Thatta and Umerkot, Sindh, alone. <strong>Oxfam</strong>and its local partner have supported some women with legal aid andhave seen success in at least 15 cases. However, the pace of decisionmakingin the revenue courts is slow. The government needs torebalance the law in favour of poor women landowners.Bonded labourAccording to the International Labour Organization (ILO) million people are estimated to be engaged in bonded labour in<strong>Pakistan</strong>, [the] majority of them are landless haris (farmers) in 19 Bonded labour is most common among agricultural workersand brick-kiln labourers, a disproportionate number of whom arewomen, alongside others from socially marginalized groups andreligious minorities. There is a direct link between a lack of land titlesor insecure tenancy and bonded labour most landless farmers andtheir families are trapped in generational bonded labour. Bondedlabour is prevalent in most of the flood-affected areas. There isanecdotal evidence that bonded labour will increase after the floodsand that conditions for bonded labourers will worsen. Flood-affectedpeople have told <strong>Oxfam</strong> and its partners of widespread coercion bylandlords, whereby they are required to hand over the cash assistancereceived through the government WATAN Card Scheme and NGOcash grants to repay debts. <strong>Land</strong>lords have also forcibly transportedfarmers from their place of displacement to return to their land to startworking again as bonded labourers. Several aid organizationsworking on housing, land, and property issues have expressedconcerns that brick-kiln workers will be in greater debt in theaftermath of the floods. 2019

Womenlost gainsThe government of Sindh was providing an agricultural supportpackage to the women who had received land under the <strong>Land</strong>Distribution Programme to help them make their land productive.However, since the floods the agricultural support has beensuspended due to the reallocation of resources elsewhere. The womenof the second phase of the <strong>Land</strong> Distribution Programme havereceived no support package and there has been no progress on thethird phase of the <strong>Land</strong> Distribution Programme. Furthermore, themajority of the women from the second phase of the <strong>Land</strong>Distribution Programme and some from its first phase are still waitingto receive their legal ownership documents (Form-7). In the chaos ofthe aftermath of the floods, there is fear that these poor womenlandowners will be more vulnerable to exploitation and illegalpossession of their land by big landlords and the politicallyinfluential.It is feared by civil society organizations (both international andnational NGOs) that progressive programmes such as the governmentin the aftermath of the floods crisis, which would be a huge loss in thecritical gains that have been made in increasing the ownership of landby women. It is vital that the government of Sindh continues to investin this scheme, ensuring that the paperwork and agricultural packagesare delivered as planned. It is also an ideal time for other provinces,with the support of the federal government, to roll out similarschemes more widely in <strong>Pakistan</strong>.20

4 Recovery andreconstruction plans: whereis land?Developing recovery plans is an opportunity for the government,international actors, national organizations, and the private sector tocontribute to minimizing the deprivation and economic vulnerability ofpoor and marginalized <strong>Pakistan</strong>is. It is the right time for thegovernment of <strong>Pakistan</strong> to show responsible leadership by urgentlyimplementing nationally led reconstruction plans for promoting landequality for poor women and men.The DNA needs to go beyond a token mention of landIn 2010 a preliminary DNA was published jointly by the WB, theADB, and the federal government, with monetized estimates of floodrelateddamage and loss of income, as well as expected the publiccosts of recovery. 21 The DNA is thus far the most detailed statement ofthe proposed strategic priorities, policy direction, and implementationarrangements for post-floods recovery and rehabilitation by thefederal government. 22 However, the DNA fails to put the needs of thelandless flood-affected at the heart of its assessment, leaving thepoorest and most vulnerable at further risk of being left behind in thereconstruction process.The DNA does mention the importance of addressing land issues andtaking special measures for targeting the landless, but it is donebroadly, without any clear guidelines or action plan. It is critical thatthe government, as it finalizes its reconstruction plans, explicitlytackles land issues.The DNA does highlight opportunities for distributing land amongthe landless, including women, when restoring livelihoods, providingbasic infrastructure during reconstruction, and establishingcomputerized and transparent land recording systems. These areimportant recommendations that the government should incorporatein its reconstruction plans. They should also be a component in thetransition and permanent shelter programmes that are being providedby international community actors as part of the relief and earlyrecovery activities.The DNA highlights that many displaced people do not own theirhomestead lands and that there might be conflicts and disputes overpost-floods demarcation of homesteads. However, there is no mentionof any specific strategy to address these land issues, nor is there anymention of a plan to conduct an assessment that analyses theproblems flood-affected people might face in accessing land as theyrebuild their lives and livelihoods. UN-HABITAT is the lead UN21

agency on housing, land, and property rights. UN-HABITAT <strong>Pakistan</strong>Reconsthighlighted the damage in detail, it did not adequately deal with thecomplexities of land access and ownership issues in the flood-affectedareas. In addition, there was no analysis of the existing powerdynamics between landless people and their landlords nor of theimpact this will have on return and reconstruction. The Housing,<strong>Land</strong> and Property (HLP) working group (consisting of a range ofnational and international actors), under the chair of UN-HABITAT,has since raised these issues and has given guidance to clusters andthe early recovery working groups on how better to tackle theseissues. 23Now is the time for government to look holistically at these landissues and, based on the findings of a comprehensive land assessment,develop a recovery plan. The recovery plan should specifically targetgroups that were vulnerable due to land insecurity even before thedisaster.Overall, the priorities in the DNA focus on landowners and thewealthy. However, the majority of the flood-affected are poor andlandless tenants or labourers. This creates a serious risk that thosewho need compensation the most, will be the ones to miss out. Thesame is true with respect to the proposed subsidies to the financialsector to help it deal with non-performing loans. Since borrowersfrom the formal sector are exclusively the bigger farmers, the primarybeneficiaries of this subsidy too will be people who are relativelybetter off such as landowners. The government must ensure that themost vulnerable receive the compensation they so desperately need.<strong>Land</strong> ownership issues are not addressed at all in the proposedhousing recovery and reconstruction strategy. The emphasis in thestrategy is on the quality and design of reconstruction and itsestimated costs. There is no costing for land acquisition by theinclude a housing reconstruction strategy and budget that gives thelandless poor legal titles and the resources to build houses that areflood-resistant. Through various forums the government hasdiscussed the option of preventing people from rebuilding houses inhigh-risk areas. Should this go ahead, the government should providealternative land for people from which they can earn a decent living.These consent, and movements should take place in accordance withminimum standards for relocation. It is important that the the issue of insecurity of land possession,especially if large numbers of landless poor people do not want toreturn to the exploitative set-up of their landlord at their place oforigin.22

Adoption of international guidelinesIt is now widely accepted, at least among the internationalcommunity, that land issues should be tackled at the beginning of acrisis response and should address pre-existing inequalities.This is essential if governments are to ensure a sustainable postdisasterrecovery and rehabilitation plan that helps to lift people outof poverty. In all the major disasters of recent years the AsiaTsunami 2005, the <strong>Pakistan</strong> Earthquake 2005 and the Haiti Earthquake2010 it was demonstrated that humanitarian as well as developmentresponses must be anchored in a rights-based framework with directtargeting of the most vulnerable and marginalized. It was also foundthat there was a need for land programming within a few weeks ofthe disaster, and that there needed to be early assessment ofinstitutions that provide access to land and protect rights to land.Vulnerable groups, including those who were vulnerable before thedisaster needed to be protected against the risk of dispossession aswell return to inequality. 24UN-HABITAT highlights two critical land issues associated withdisasters. First, there is the concern that a crisis triggered by disastersmight be exacerbated for many people due to the threat ofdispossession if land records are uneven or of poor quality, or wherepower relations might place some displaced persons at adisadvantage. Second, where pre-disaster conditions were themselvesmarked by inequality and insecurity, post-disaster responses need tocreate more secure tenure and rights for the poor and themarginalized in general, and women in particular. 25None of this has been done in post-floods <strong>Pakistan</strong>. Hence, thegovernment and international donor community should incorporatethe key international guidelines on land into the recovery andreconstruction plans as a matter of priority. The first important step isto ensure that a land needs assessment takes place within the first sixweeks of any disaster (as per UN-must also be a clear plan for ensuring that poor people who have beenaffected by disasters are protected from land grabs by landlords.Reconstruction plans need to tackle land rights more effectivelyThe gexplicitly and effectively. The plans should include the provision oflegal support to settle land disputes, with government revenueofficials designated to give speedy service for land demarcation andupdating lost land records. The provincial government should alsoensure that landlords are allowing tenants to return to the land, andthat compensation is given to the landless poor for reconstructinghouses and rehabilitating agricultural land. This is a criticalopportunity to allot land to the landless poor, especially women, andthereby address the fundamental issues of land inequality. The federaland provincial governments should learn from schemes like thegovernment of Sindh <strong>Land</strong> Distribution Programme and Jinnah Abadi Scheme, which provides formal settlements for those23

without shelter, and ensure these and other schemes continue and arereplicated in other provinces.Holistic plan that looks at social protection, agriculture and disasterrisk reductionThe reconstruction plans need to have a holistic approach andexplicitly address the vulnerabilities of the landless poor. The plansshould move away from the past approach of targeting wealthylandowners, and instead target the landless poor. Agriculturalinvestment should focus on ensuring that the landless poor have easyaccess to productive, rehabilitated land. The private landlords in thearea should be held accountable for the restoration of damagedirrigation structures and for adequately addressing disaster riskreduction measures.Now is also the time to address the issue of bonded labour.Conversations that <strong>Oxfam</strong> and its partners have had with floodaffectedpeople have highlighted cases where landlords have forcedpeople to come back to their land as bonded labourers and have takenrepayment of debts from WATAN card funds. Even before the floods,civil society organizations were working on the issue of bondedlabour and advocating to the government to declare as illegal the debtof bonded labourers. The government must tackle this issue to ensurethat landlords cancel the debts that keep the landless poor ingenerational debt.The government should also provide better social protection andsupport to landless and tenant farmers, especially in times of crisis, asthese are the people who most need support. <strong>Land</strong>lords continue toexploit landless people through the WATAN Card Scheme. Currently,land ownership or secure title is not a pre-condition for eligibility forthe WATAN Card Scheme, but possessing a CNIC has been a precondition.This has posed a problem for landless women and menwho have been dependent on their landlords to verify their addressesfor their CNICs. It has also left landless <strong>Pakistan</strong>is more exposed toexploitation by landlords. Flood-affected people have told <strong>Oxfam</strong> andits partners that often when people have received payment via theWATAN Card Scheme, a percentage has been given to landlords forverifying their addresses. People living in katcho areas have also saidthat their cards had to be linked to the addresses of relatives whoreside in the settled part of the district. 26 affected by the floods, this has posed a problem in getting thecompensation. This highlights how insecure landless people are andhow dependent they are on others to receive compensation orbenefits.Additionally, it is important that the landless poor are freely allowedto rebuild their houses and that these new houses are flood-resistantand are at a reduced risk from the next disaster. The governmentshould ensure that housing compensation is flexible enough for thelandless poor to rebuild to standards that best suit their livingenvironment and allows for building flood-resistant structures.24

Box 3A timely reminder of the pitfallsof land inequality is to be foundin Balakot, Manshera innorthern <strong>Pakistan</strong>, where postearthquakeplans to relocatethe town to a new modelvillage location were nevercompleted, despite moneycommitted and constructionstarted. This was heralded bydonors in much the samemanner as current plans, onlyto see limited buy-in fromcommunities.According to the EarthquakeRehabilitation andReconstruction Authorityprogress report of June 2008,land under acquisition for thispurpose was worth Rs1.5bn or$17.5m.Involving communitiesCivil society actors have raised the concern that the DNA has notadequately involved communities affected by the floods. Provinciallevel authorities have also been moving forward with various plansthat have a significant impact on land rights, but without adequatelyinvolving civil society, especially the flood-affected landless poorthemselves. An example of this is policy of model villages. Althoughnot new to <strong>Pakistan</strong>, such endeavours must be grounded inmeaningful participation of communities, with sufficient attentionpaid to the economic and cultural impact of such moves. Both theprovincial and federal government must recognize that the key todisaster resilience lies with involving affected communities as well asstate structures in these processes. The provincial authorities inPunjab and Sindh have discussed the construction of model villagesfor flood-affected people. Such initiatives can only hope to besuccessful by prioritizing the meaningful participation ofcommunities and critically assessing their indirect impact on. Box 3 outlines thechallenges that were faced during the model village initiatives afterthe 2005 earthquake. Models for community involvement in restoringlivelihoods and land do exist: development actors such as <strong>Oxfam</strong> haveconducted numerous successful projects working with local partnersand grassroots groups.<strong>Land</strong> governanceBox 4of gigantic powers in front ofme. Knowing nothing about thecourt system and spendingmonths not able to cultivate myland. I thought as fate wouldhave it my family and I wouldnever have a life of ease when we had been so close tobecoming landlords. Thesupport of <strong>Oxfam</strong> and its localpartner, PDI has given me theconfidence to speak for myrights. These are tears of joynow after having won my casein the revenue court ofExecutive District OfficerRaheeman Natho Mallahbelongs to the small village ofTaluka Jati, district Thatta.The land administration system has many weaknesses. There is stillno computerized land records system in <strong>Pakistan</strong>, meaning that all ofthe land records are paper files that are usually not updated. Thesystem is official who surveys the land and accordingly updates ownership andtenancy records). Over the years the patwaris have developed anexploitative attitude and only update records if there is a bribe orpatronage to be gained. This has resulted in a TransparencyInternational corruption perception report highlighting landadministration as one of the most corrupt departments in <strong>Pakistan</strong>. 27Senior government revenue officials and parliamentarians mustrecognize the importance of reducing the powers of the patwaris andimproving the land administration procedures. A key step inaddressing the issue of lack of up-to-date records and corruption is tocomputerize all land records.There is also the issue of inadequate and slow support from thejudicial system for poor people, especially women, when addressingland disputes. There are numerous examples from the government ofSindh <strong>Land</strong> Distribution Programme where women who were allottedland by the government had to wait months to get a decision in theirfavour. During this time they could not cultivate that land and theylost several seasons when they could have earned an income from thetto get justice from the revenue courts is not only an economicstruggle, but an emotional one and one which is quite often a long,drawn-out process.25

Similarly, in the post-earthquake situation in <strong>Pakistan</strong> there were asmany as 5,000 landless families (around 8 per cent of the total peopleaffected) who remained without adequate housing for two years afterthe disaster. 28 Families who had been able to leave behind able-bodiedmen to physically guard their land were better able to secure theirrights compared with those who had lost all their able-bodied men.There is an urgent need to provide a timely grievance redressalmechanism for those women who have received land under thegovernment scheme as well as flood-affected people regarding landdocuments and resolving land demarcation cases. The governmentneeds to have dedicated resources at the district level, through a legalassistance cell in the district revenue department, that provides timelysupport and especially caters to facilitating women applicants.26

5 Conclusion andrecommendationsIn <strong>Pakistan</strong>, effective recovery from the floods will not be possiblewithout improving land inequality. All stakeholders, includinglandlords and the politically influential elite, need to play aconstructive and positive role in the recovery and reconstructionprocess. This must be done by addressing the decades-old cause ofpoverty and deprivation land inequality.A serious effort needs to be made to immediately address land issuesin recovery and reconstruction plans, and both federal and provinciallevel recovery and reconstruction plans must clearly spell out theirstrategy and programmes, with dedicated resources for taking actionon this issue.This is an opportunity to build a better <strong>Pakistan</strong> where the poorestpeople, especially women, can sleep at night, knowing they have awhich they can earn a living. A range of solutions will be needed toachieve this, including strong tenancy rights that are realized, andmore equitable ownership of land, especially for the sociallymarginalized like women and religious minorities.The government of <strong>Pakistan</strong> should:immediately conduct a comprehensive review of land issues inthe flood-affected areas to find out the challenges, needs, andvulnerabilities of the landless and land insecure population;;at all levels (both federal and provincial) explicitly incorporateland issues and land inequality in recovery and reconstructionplans, with dedicated resources;;provide land to landless women and men for homesteads ineconomically viable locations, and if necessary acquire land forthis purpose;;land distribution programmes such as the government ofAbadi Scheme;;computerize all land records so there is less loss of landrevenue records and a more transparent system of recordingland ownership.27

The WB and ADB should:support the government of <strong>Pakistan</strong> in incorporating landissues and addressing land inequality in recovery andreconstruction plans by providing both financial and technicalresources;;modify their own policies and programmes to focus more onthe landless and vulnerable rather than wealthy landowners;;support the government of <strong>Pakistan</strong> in computerizing landrecords.The UN should:ensure that post-disaster responses create more secure tenureand land rights for the poor and the marginalized in general,and women in particular;; to this end, to fully implement UN-HABITAT and UN-FAO guidelines for rapid tenure securitymeasures for returnees, protection and restoration of landrights of vulnerable groups, and secure rights and access toagricultural land for vulnerable groups, including tenants andwomen;;support governments in conducting land needs assessmentswithin the first six weeks of any disaster;;develop programmes that safeguard landless women andmen against arbitrary land grabbing.<strong>Land</strong>lords should:show leadership in the recovery and reconstruction effort bywriting off the debts of small farmers;;play a constructive role as wealthy landowners and contributeto the rehabilitation of damaged and destroyed irrigationstructures so that landless and poor tenants can resumeagricultural activities quickly;;responsibly uphold tenancy rights under the Tenancy Act byallowing the re-entry of those who had been on their landbefore the floods (without embarking on exploitativerenegotiated terms) and to facilitate the swift reconstruction ofhomes on their properties.Civil society and the media should:play an active role in highlighting the issue of land inequalityand hold the government, the international donor community,and landlords accountable for adequately addressing land28

issues in recovery and reconstruction plans by monitoringprogress, holding public meetings, and ensuring thatmeaningful consultations are held with affected people;;ensure NGO plans to tackle housing and shelter recovery andreconstruction take into account land inequality issues,especially the risk that poor people may face dispossessionfrom their homes where land rights are not assured.29

<strong>Note</strong>s and References1 Official <strong>Pakistan</strong> floods response website.http://floods2010.pakresponse.info/FactsandFigures.aspx2 According to the preliminary Damage and Needs Assessment (DNA) by the WorldBank and Asian Development Bank (November 2010), some aid actors and<strong>Pakistan</strong>i officials believe that the actual figures are higher. The Shelter ClusterMeeting Summary (11 January 2011) gives an example of the kind of discrepancies-November but haveproved to display big discrepancies when compared to the PDMA figures at districtlevel. Field investigations by National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) inearly January 2011 have confirmed the veracity of the PDMA (Provincial DisasterManagement Authority) figures. For example, in Dadu the DNA figures detail 24,000damaged or destroyed homes, while the Floods: Preliminary Damage and Need Assessment 2010.3 Situational and Power Analysis,<strong>Oxfam</strong> Research Report.4 Gazdar, Haris (M Situational and Power Analysis,<strong>Oxfam</strong> Research Report.5 A study carried out in 49 districts of Punjab and Sindh confirms that deprivation andpoverty in high land inequality districts is about 10 per cent higher than in relativelylower land inequality districts. Social Policy Development Centre SPDC (2004)Social Development in <strong>Pakistan</strong>, 6 . Ottawa, Canada: InternationalDevelopment Research Centre. Available at:http://www.shirkatgah.org/_uploads/_files/f_17-Women_access-rightsto_land_property_in_<strong>Pakistan</strong>.pdf7 The tenancy laws are enacted by Parliament to regulate the relationship between the<strong>Pakistan</strong> as a parcel of land held by a tenant of the landlord under one lease, andthe tenant as a person who holds land under the landlord and would be liable topay rent for that land. Its purpose is to accommodate landless people and toprovide them with cover and support against the landowners and landlords. Eachof the four provinces of <strong>Pakistan</strong> have their own tenancy laws: the PunjabTenancy Act, Sindh Tenancy Act, KPK (previously known as NWFP) Tenancy Actand Balochistan Tenancy Act were enacted in 1887, 1950, 1950, and 1978,respectively.8 Gazdar (2010) op cit.9 The Journal for Peasant Studies 33 (3):479501.10 farm,analysis and interview with the leader of Aujuman Mazarain Punjab, The News ofSunday, 19 April.11 Dawn News, 10 September.Available at: http://archives.dawn.com/archives/6111712 Pakkisan.com, 14 October. Available at:http://www.pakissan.com/english/news/newsDetail.php?newsid=2181913 General Zia-ul-Haq set up Shariat Courts at provincial and federal level. In August1989 the Supreme Court Shariat Appellate Bench issued a majority judgment thatthe land reforms of 1977 were invalid and against the injunctions of Islam.14 Social Development in <strong>Pakistan</strong>:Combating Poverty. Is Growth Sufficient? Annual review. Karachi, <strong>Pakistan</strong>: SocialPolicy and Development Centre (SPDC), 15 Cohen, Stephen P. (2011) The Future of <strong>Pakistan</strong>. Washington, DC: The BrookingsInstitution, p.24. Available at:http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/rc/papers/2011/01_pakistan_cohen/01_pakistan_cohen.pdf16 elections. Since they are more or less dependent on the landlord for access toland for both agriculture and housing, they are a guaranteed vote-bank for thatlandlord. In turn, the more politically powerful the landlord, the more he is able to30

facilitate secure access to land.17 In their post-floods guidelines the Housing, <strong>Land</strong> and Property <strong>Rights</strong> (HLP)Working Group came up with 13 categories of people affected by the 201011floods. (Final Draft on <strong>Land</strong> Guidelines, 22 October 2010.)18 Assessme, June 2011.19 tbl, 15 June. Available at: http://www.tbl.com.pk/the-menace-of-bonded-labour-inpakistans-agricultural-sector/20 21 ADB/WB/GOP (2010) <strong>Pakistan</strong> Floods 2010: Preliminary Damage and NeedsAssessment. Islamabad: Asian Development Bank, World Bank and governmentof <strong>Pakistan</strong>.22 According to sector-wise estimates provided in the DNA, the total economic lossesincurred as a result of the floods amounted to Rs 854 billion ($10 billion). Directdamage to assets, stocks and inventories, including housing, agriculture, livestockand public infrastructure, was Rs 552 billion rupees, out of which housing (Rs 91billion) and agriculture (Rs 315 billion) accounted for the largest share. The cropsub-sector within agriculture was estimated to have suffered direct losses of Rs287 billion. All this damage is closely linked to investment that was made torehabilitate land for agriculture, housing and shelter and those feeling the impactthe most are the vulnerable and uninsured small farmers.23 Emerging Lafor clusters and early recovery working groups for emerging issues on land andproperty rights issues. These issues were discussed and given asrecommendations by the HPL Working Group to the Protection Cluster.24 UN-HABITAT (2010) Nairobi: UN-HABITAT and UN FAO.25 UN--HABITAT.26 The incomplete coverage of the katcho areas is also acknowledged by NationalDatabase and Registration Authority (NADRA) which announced that it would takemeasures to overcome this gap. It is also widely reported that durable constructionwas barred by law in the katcho area (DNA 2010, p 157).27 Transparency International (2010) National Corruption Perception Survey, <strong>Pakistan</strong>.28 UN--HABITAT.All websites accessed 25 May 2011.31

© <strong>Oxfam</strong> International June 2011This paper was written by Fatima Naqvi and Haris Gazdar, and coordinatedby Azmat Budhani and Haris Gazdar. Thanks are due to <strong>Oxfam</strong> colleagueswho contributed to its development, particularly Michel Anglade, ShaheenChughtai, and Helen McElhinney. This report is part of a series of papers on<strong>Pakistan</strong> written to inform public debate on development and humanitarianpolicy issues.This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for thepurposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided thatthe source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that allsuch use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. Forcopying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or fortranslation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may becharged. Email publish@oxfam.org.uk.For further information on the issues raised in this paper, please emailadvocacy@oxfaminternational.org.The information in this publication is correct at the time of going to press.Published by <strong>Oxfam</strong> GB for <strong>Oxfam</strong> International under ISBN978-1-84814-809-3 in January 2011. <strong>Oxfam</strong> GB, <strong>Oxfam</strong> House, John SmithDrive, Cowley, Oxford, OX4 2JY, UK.<strong>Oxfam</strong><strong>Oxfam</strong> is an international confederation of fourteen organizations workingtogether in 99 countries to find lasting solutions to poverty and injustice:<strong>Oxfam</strong> America (www.oxfamamerica.org),<strong>Oxfam</strong> Australia (www.oxfam.org.au),<strong>Oxfam</strong>-in-Belgium (www.oxfamsol.be),<strong>Oxfam</strong> Canada (www.oxfam.ca),<strong>Oxfam</strong> France (www.oxfamfrance.org),<strong>Oxfam</strong> Germany (www.oxfam.de),<strong>Oxfam</strong> GB (www.oxfam.org.uk),<strong>Oxfam</strong> Hong Kong (www.oxfam.org.hk),Intermón <strong>Oxfam</strong> (www.intermonoxfam.org),<strong>Oxfam</strong> Ireland (www.oxfamireland.org),<strong>Oxfam</strong> Mexico (www.oxfammexico.org),<strong>Oxfam</strong> New Zealand (www.oxfam.org.nz)<strong>Oxfam</strong> Novib (www.oxfamnovib.nl),<strong>Oxfam</strong> Quebec (www.oxfam.qc.ca)The following organizations are currently observer members of <strong>Oxfam</strong>,working towards full affiliation:<strong>Oxfam</strong> India (www.oxfamindia.org)<strong>Oxfam</strong> Japan (www.oxfam.jp)<strong>Oxfam</strong> Italy (www.oxfamitalia.org)Please write to any of the agencies for further information, or visitwww.oxfam.org. Email: advocacy@oxfaminternational.orgwww.oxfam.org32