Achieving Improved Primary and Secondary Education ... - AMP

Achieving Improved Primary and Secondary Education ... - AMP

Achieving Improved Primary and Secondary Education ... - AMP

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

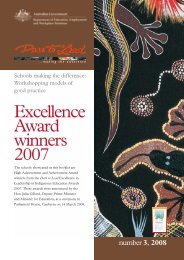

Our Children,Our Future –<strong>Achieving</strong> <strong>Improved</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Secondary</strong> <strong>Education</strong>Outcomes for Indigenous StudentsAn overview of investment opportunities <strong>and</strong> approachesA REPORT PUBLISHED BY

There has been tacitacceptance of the non-achievementof educational st<strong>and</strong>ards byAboriginal children <strong>and</strong> young people.The resultant acceptance of thislack of educational success has acumulative effect. It is based on thebelief that Aboriginal children <strong>and</strong>young people will never reach theirfull potential <strong>and</strong> if they fall behindsociety then welfare will protectthem. Their low level of educationalsuccess is accepted as a normativeexpectation.1This has to change.Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: Improving the<strong>Education</strong>al Experiences of Aboriginal Children <strong>and</strong> Young People1 Zubrick S, De Maio J, Shepherd C, Griffin J, Dalby R, Mitrou F, Lawrence D, Hayward C, Pearson G, MilroyH, Milroy J, Cox A. The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: Improving the <strong>Education</strong>alExperiences of Aboriginal Children <strong>and</strong> Young People. Perth: Curtin University of Technology <strong>and</strong> TelethonInstitutes for Child Health Research, 2006, p.vi. (Zubrick et al. 2006)

Foreword by Tom CalmaAccess to education is a basic human right enshrined inthe Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Most peoplenow accept that education is the key to improving lifechances <strong>and</strong> life choices. An education leads us to greateropportunities to participate in employment <strong>and</strong> in thewider society. This in turn can lead to other benefits such asimproved emotional <strong>and</strong> social wellbeing <strong>and</strong> better accessto services such as housing <strong>and</strong> health care.To m Ca l m aA b o r i g i n a l & To r r e s St r a i t I s l a n d e rS o c i a l J u st i c e Co m m i s s i o n e rN at i o n a l R ac e D i s c r i m i n at i o nCo m m i s s i o n e rH u m a n R i g h ts a n d E q ua l O p p o rtu n i t yCo m m i s s i o nIndigenous Australia has a population of over half a million people <strong>and</strong> it isgrowing. Unfortunately for this growing population, the education statisticspaint an alarming picture. Indigenous youth remain the most educationallydisadvantaged group in Australia. In many parts of Australia they aredisadvantaged in terms of access to appropriate <strong>and</strong> high quality education, <strong>and</strong>as a consequence many are not reaching the basic educational milestones. Theextent of this disadvantage <strong>and</strong> the challenges <strong>and</strong> opportunities to overcomethis disadvantage are well documented in this Report.While at present there are large challenges, improvements can be made withappropriate policies, funding <strong>and</strong> partnerships between government, educationproviders <strong>and</strong> communities. Strategies <strong>and</strong> resources that are commensuratewith this long-term challenge are urgently needed. Investment in Indigenouseducation needs to be significant, <strong>and</strong> at all levels. Recruitment programs,skill development <strong>and</strong> employment retention programs are required so thatthe Indigenous labour market increases rather than decreases. Every schoolcommunity needs a quantum of Indigenous teachers so that liaison betweenthe Indigenous home <strong>and</strong> school environments is managed by a large, enabledIndigenous workforce. Indigenous teachers <strong>and</strong> teachers’ aides need to be wellresourced<strong>and</strong> provided with first class professional learning <strong>and</strong> developmentopportunities. The best <strong>and</strong> brightest non-Indigenous teachers need to beencouraged to work in remote Indigenous schools. <strong>Education</strong> facilities need to beof the same st<strong>and</strong>ard across the country. There is much work to be done.This Report will assist you to underst<strong>and</strong> the current challenges in Indigenouseducation. It will also clarify the role that the philanthropic sector can play inassisting to close the gap between Indigenous <strong>and</strong> non-Indigenous educationalopportunities <strong>and</strong> outcomes. This is an important challenge <strong>and</strong> we must all workin partnership to make a difference. I hope you will lend your support.I commend this report to you.

About this PublicationThis Report has been published in collaborationby The <strong>AMP</strong> Foundation, Effective Philanthropy<strong>and</strong> Social Ventures Australia. It is based on anearlier report on Indigenous education preparedfor, <strong>and</strong> funded by, the <strong>AMP</strong> Foundation. The <strong>AMP</strong>Foundation has generously agreed to support theextension <strong>and</strong> publication of the earlier report forthe benefit of the broader philanthropic sector.This work is copyright apart from any use aspermitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Youmay copy this Report for your own personal use <strong>and</strong>research or that of your firm or company. You maynot republish, retransmit, redistribute or otherwisemake the Report available to any other party withoutwritten permission from the Authors.Copies of the Report are available for download atthe publishing organisations’ websites. Requests<strong>and</strong> inquiries concerning reproduction should beaddressed to the publishing organisations throughone of the contacts listed here.In all cases the Report must be acknowledged as thesource when reproducing or quoting any part of thispublication.For any inquiries in relation to this Report pleasecontact:The Publishing OrganisationsThe <strong>AMP</strong> Foundation – www.amp.com.au<strong>AMP</strong> has been contributing to the Australiancommunity for more than 150 years. The <strong>AMP</strong>Foundation was established in 1992 <strong>and</strong> is one of thevehicles through which <strong>AMP</strong> invests in the community.Our purpose is to make a difference in the Australiancommunity at a grassroots level, where <strong>AMP</strong> peoplelive <strong>and</strong> work. Based on the philosophy of offering a‘h<strong>and</strong> up <strong>and</strong> not a h<strong>and</strong>out’, the Foundation investsin two key areas – Capacity Building <strong>and</strong> CommunityInvolvement.Our Capacity Building programs encourage <strong>and</strong>support people to help themselves. Our effortsare especially focused on young people <strong>and</strong> thesustainability of the not-for-profit sector.Our Community Involvement programs encourage <strong>and</strong>support people to help others. We focus on supportingthe work of <strong>AMP</strong> employees <strong>and</strong> <strong>AMP</strong> financialplanners in the community.–––Authors Louise Doyle or Regina Hillinfo@effectivephilanthropy.com.auThe <strong>AMP</strong> Foundationamp_foundation@amp.com.auSocial Ventures Australiadpeppercorn@socialventures.com.auNotice <strong>and</strong> DisclaimerThe <strong>AMP</strong> Foundation, Effective Philanthropy <strong>and</strong>Social Ventures Australia shall not be liable for lossor damage arising out of or in connection with theuse of this Report. This is a comprehensive limitationof liability that applies to all damages of any kind,including without limitation compensatory, direct,indirect or consequential damages, loss of data,income or profit, loss of or damage to property <strong>and</strong>claims of third parties.Effective Philanthropy –www.effectivephilanthropy.com.auEffective Philanthropy is a research consultancy thatworks to identify, promote <strong>and</strong> pilot innovative <strong>and</strong>effective approaches to social <strong>and</strong> environmentalissues. It seeks to do that through the preparationof social issue reports to inform intervention design,social policy definition <strong>and</strong> philanthropic investment.Effective Philanthropy works with philanthropiststo assist them in identifying <strong>and</strong> funding effectiveresponses to social <strong>and</strong> environmental issues.Effective Philanthropy assists in the design, pilot <strong>and</strong>evaluation of innovative not-for-profit interventionprograms <strong>and</strong> collaborates with philanthropists <strong>and</strong>the organisations that they fund to improve theeffectiveness of program delivery.

a b o ut t h i s p u b l i c at i o nSocial Ventures Australia –www.socialventures.com.auSocial Ventures Australia (SVA), an independentnon-profit organisation established in 2002, is anew model of social investment that aligns theinterests of philanthropists with the needs of socialentrepreneurs to combat some of Australia’s mostpressing community challenges.With a focus on accountability <strong>and</strong> impact, SVAprovides funding, mentoring <strong>and</strong> organisationaltools to a carefully selected portfolio of nonprofitorganisations led by outst<strong>and</strong>ing socialentrepreneurs. In doing so, we seek to boost theireffectiveness, efficiency, capacity <strong>and</strong> sustainabilitythrough our h<strong>and</strong>s-on approach – supporting theirprograms to grow <strong>and</strong> mature so that they are ableto create sustainable <strong>and</strong> lasting change.SVA also offers consulting services to the nonprofitsector, <strong>and</strong> to philanthropic organisations<strong>and</strong> individuals. These focus on helping non-profitsto develop <strong>and</strong> implement their strategic plans, toimprove their operations <strong>and</strong> to demonstrate theirimpact. We work with funders including foundations,philanthropists <strong>and</strong> governments to demonstratefunding impact, to improve funding efficiency <strong>and</strong>to identify organisations that deliver demonstrableoutcomes. SVA’s consulting services complementSVA’s program of workshops <strong>and</strong> mentoring services.SVA has conducted a range of research in the areacovered by this Report. It has prepared knowledge<strong>and</strong> information papers <strong>and</strong> in 2007 it conductedan Indigenous roundtable investigating Indigenouseducation <strong>and</strong> transitions to work. SVA’s work inthese areas is ongoing.The AuthorsLouise DoyleStanford Executive Program for Philanthropy Leaders,BA, Certificate in Public Relationslouisedoyle@effectivephilanthropy.com.auLouise Doyle is a principal with EffectivePhilanthropy. Louise works as a consultant in the notfor-profitsector providing advice to philanthropicinvestors in relation to their investment strategy <strong>and</strong>grant making. She is also the Executive Officer ofThe Becher Foundation.Regina HillMaster International Laws, MBA, BA/LLB Honsreginahill@effectivephilanthropy.com.auRegina Hill is a principal with Effective Philanthropy.Regina works as a consultant <strong>and</strong> researcher inthe commercial <strong>and</strong> not-for-profit sectors. She hasa special interest in issues relating to Indigenousaffairs, early childhood development, children <strong>and</strong>young people at risk, education <strong>and</strong> mental health.AcknowledgementsThe Authors are grateful to Chris Boys <strong>and</strong> HelenStanley for the support that they provided in relationto the preparation of earlier versions of this Report.They also thank Dr. Jo Stubbings for editing thisReport.The publishing organisations are grateful to thefollowing subject matter experts who have reviewedthis Report:– Adrian Appo, Executive Officer, Ganbina KooriEconomic <strong>and</strong> Employment Agency– Dr Barry Osborne, Adjunct Associate ProfessorJames Cook University <strong>and</strong> Djarragun CollegeBoard Member– Jennifer Samms, Executive Director, Taskforce onAboriginal Affairs, Department of Planning <strong>and</strong>Community Development Victoria– Dr Nereda White, Coordinator, WeemalaIndigenous Unit, Australian Catholic UniversityNationalThe publishing organisations are grateful for theinput provided by the Review Panel. The publishingorganisations take full responsibility for the viewsexpressed in this Report <strong>and</strong> note that any errors oromissions are their responsibility <strong>and</strong> not those ofanyone consulted in the process of preparingthe Report.

Table of contentsPage Section6 1. Executive summary10 2. Introduction11 2.1 Purpose of this Report11 2.2 Scope of this Report12 2.3 Who will find this Report useful <strong>and</strong>how?13 2.4 Methodology used to prepare this Report14 3. Background16 3.1 The objectives of education16 3.2 The Australian education system19 3.3 The Indigenous student population19 .3.1 Overall Indigenous population –a contextual overview20 .3.2 Student population profile22 3.4 Government-based Indigenous-specificeducation initiatives25 4. Indigenous educationoutcomes28 4.1 Attendance28 .1.1 Preschool attendance29 .1.2 School attendance30 4.2 Retention31 4.3 Student performance <strong>and</strong> achievement32 4.4 Post-secondary qualifications33 4.5 Labour force participation <strong>and</strong>employment (positive transitions fromschool to work)34 4.6 Socio-economic status35 4.7 Individual wellbeing36 5. Factors contributing topoor Indigenous educationoutcomes37 5.1 Underlying conceptual framework39 5.2 Social or community context41 5.3 Home context43 5.4 School context48 5.5 Student contextPage Section49 6. Intervention options50 6.1 The role of the philanthropic sector51 6.2 Considerations when investing in theIndigenous sector52 6.3 Identified intervention options54 6.4 Key success factors56 6.5 Detailed intervention summaries56 6.5.1 Holistic schooling approach58 6.5.2 Tailored curriculum59 6.5.3 Appropriate staff training60 6.5.4 Holistic student support62 6.5.5 Student <strong>and</strong> parental engagement66.5.6 Intensive learning support66 6.5.7 School-based vocational training<strong>and</strong> development programs68 6.5.8 Scholarship programs70 7. Conclusion71 7.1 Key insights for philanthropic investment72 7.2 Final words73 Glossary of Terms75 References77 Acknowledgements78 Appendix One – Factors identified as affectingIndigenous student absenteeism79 Appendix Two – Detailed description of school<strong>and</strong> student-based change levers

1. Executive summaryFor a number of years Australian Governments have soughtto position Australia as the ‘Clever Country’. They havepromoted the importance of education <strong>and</strong> training as thefoundation for our economic prosperity <strong>and</strong> future growth.In the case of Indigenous Australians, however, education<strong>and</strong> training arguably hold even greater significance as theyprovide the key not only to economic prosperity but also tosocial equality.

1 . e x e c utive summaryIn Australia today Indigenous students at alllevels experience worse education outcomes thannon-Indigenous students. 2 Indigenous studentsdemonstrate lower school attendance, retention<strong>and</strong> achievement than non-Indigenous studentsacross all age groups <strong>and</strong> all States <strong>and</strong> Territories. 3Indigenous post-school qualifications, labour forceparticipation <strong>and</strong> employment rates are also lowerthan those of non-Indigenous Australians 4 as istheir general socio-economic status, health <strong>and</strong>wellbeing. 5Historically, poor Indigenous education outcomes arereflected in low economic participation.These outcomes have been linked to the historicalexclusion of Indigenous people from the Australianeducation system, both formally through pastgovernment policy <strong>and</strong> informally through thefailure to deliver education services that meet theneeds of Indigenous students.In order to improve Indigenous education outcomesthere is a need to address a range of factors thatnegatively impacts the ability of Indigenous studentsto access <strong>and</strong> to engage successfully in education.This Report seeks to provide insight into the rolethat can be played by the philanthropic sector tohelp improve the education outcomes of Indigenousyoung people in Australia.The area of education is broad <strong>and</strong> the issuesimpacting the effectiveness of Indigenous educationare complex. For that reason this Report has focusedon the specific challenges <strong>and</strong> opportunities relatingto primary <strong>and</strong> secondary school level education(Years 1 to 12).2 Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision.Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2007 Overview.Canberra: Productivity Commission SCRGSP, 2007, p.4. (SCRGSPOverview 2007)3 Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision.Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2007. Canberra:Productivity Commission SCRGSP, 2007, pp.13–14. (SCRGSP 2007)4Ibid., pp.14–16, 13.2, 13.11.<strong>Primary</strong> <strong>and</strong> secondary education is only oneelement of a broader education system that startswith early childhood development <strong>and</strong> pre-primaryschooling <strong>and</strong> extends through to vocational <strong>and</strong>tertiary education <strong>and</strong> the transition from schoolto post-school employment. In choosing to focuson Years 1 to 12 education, we are not seeking todowngrade the importance of those other areas,which clearly play an important role in Indigenouseducation <strong>and</strong> the translation of education outcomesinto labour force participation <strong>and</strong> employment.Indeed, each area could be the subject of aseparate report.This Report provides an overview of the state ofIndigenous primary <strong>and</strong> secondary educationoutcomes in Australia <strong>and</strong> the impact that they haveon the capacity of Indigenous students to accesspost-secondary qualifications <strong>and</strong> employmentopportunities.The Report identifies the underlying factors thatcontribute to those outcomes, including the Social/Community <strong>and</strong> Home Contexts in which Indigenousstudents live, the School Context in which theyparticipate <strong>and</strong> their own personal life experience(referred to as Student Context).It also discusses some of the approaches that arebeing taken by the not-for-profit sector to addressthose factors. In doing that, the Report seeks tofocus on approaches that are related to the way inwhich schooling is delivered, the experience thatstudents have of school <strong>and</strong> their capacity to access<strong>and</strong> to engage in school <strong>and</strong> to learn. The Reportdoes not investigate interventions that seek toaddress broader Social issues (e.g. health, housing<strong>and</strong> community function) or Home-based issues (e.g.parenting <strong>and</strong> parental education <strong>and</strong> employment)affecting the capacity of Indigenous students toaccess or to engage in education. It also does notcover government-funded activity.5 SCRGSP Overview 2007, pp.12, 18–23; Australian Bureau of Statistics.The Health <strong>and</strong> Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres StraitIsl<strong>and</strong>er Peoples. Cat. no. 4704.0. Canberra: ABS, 2005. (ABS 4704.0)

1 . e x e c utive summaryThe Report identifies eight Intervention Categoriesthat work within a School <strong>and</strong> Student Contextto improve the delivery of education <strong>and</strong> theeducation outcomes of Indigenous students thatare suited to philanthropic investment on the basisthat they either augment or complement existinggovernment funding or provide an opportunity forthe philanthropic sector to invest in more innovativeresponses to issues affecting Indigenous education.The eight Intervention Categories covered in thisReport include:1.2.3.4.Holistic Schooling Approach – the adoption ofa holistic approach to schooling that delivers aculturally <strong>and</strong> contextually relevant <strong>and</strong> capabilityappropriate curriculum that relates students’learning to their life experience. Such schoolingapproaches incorporate program elements thataddress the full range of student needs (includingtheir basic material needs, travel to <strong>and</strong> fromschool, health <strong>and</strong> nutrition, personal <strong>and</strong>learning support requirements). They provide ahighly supportive school environment <strong>and</strong> engagestudents, family <strong>and</strong> community in the design/delivery of day-to-day schooling.Tailored Curriculum – the development <strong>and</strong>dissemination of a culturally <strong>and</strong> contextuallyrelevant <strong>and</strong> capability appropriate curriculumthat is tailored to the needs of Indigenousstudents <strong>and</strong> teaching tools to supportIndigenous student learning.Appropriate Staff Training – the development <strong>and</strong>delivery of culturally appropriate <strong>and</strong> capabilityrelevant pre- <strong>and</strong> in-service principal, teacher<strong>and</strong> teaching support staff training that includesskills relating to the design <strong>and</strong> delivery of thecurriculum as well as the establishment <strong>and</strong>management of supportive teacher–studentrelationships.Holistic Student Support – the delivery of school<strong>and</strong> non-school-based programs that specificallyseek to meet students’ individual needs byassisting them to access <strong>and</strong> engage in schoolincluding material, personal <strong>and</strong> learning supportrequirements <strong>and</strong> to promote parental <strong>and</strong> familysupport for student education <strong>and</strong> learning.5.6.7.8.Student <strong>and</strong> Parental Engagement – the deliveryof school <strong>and</strong> non-school-based programs thatspecifically seek to engage students with school<strong>and</strong> learning by encouraging school attendance,attachment <strong>and</strong> retention by promoting parental<strong>and</strong> family support for student education,connecting parents with school <strong>and</strong> helpingparents to better support their children to learn.Intensive Learning Support – school <strong>and</strong> nonschool-basedprograms that seek to provideintensive learning support including remedialliteracy <strong>and</strong> numeracy programs, generalcurriculum-based learning support or tutoring,extension learning <strong>and</strong> homework support.School-based Vocational Training <strong>and</strong>Development – school-based vocationaldevelopment <strong>and</strong> training programs includingcareer planning, school-based apprenticeships<strong>and</strong> TAFE programs etc.Scholarships – the provision of scholarships tosupport Indigenous student access to education.This Report provides case studies of each of theabove Intervention Categories in order to providea sense of how they operate. (These case studiesare provided by way of example only <strong>and</strong> theirinclusion in the Report should not be seen as arecommendation for funding.) Having analysed eachof the above Interventions we have also identifiedthe types of Key Success Factors that apply to eachof the Intervention Categories <strong>and</strong> which can helpphilanthropic investors to assess the effectivenessof individual intervention programs.The Report concludes with some insights forphilanthropic investors when investing in this area.When reviewing programs that seek to improveIndigenous education outcomes, it is rare for a singleprogram to address the range of outcomes or factorsthat often need to be addressed to support change.In many (if not most) cases a mix of interventions isrequired to do that.The strongest intervention models tend thereforeto be multi-faceted <strong>and</strong> to involve the coordinationof a range of programs to address the issuesaffecting students’ capacity to engage with school<strong>and</strong> learning. The key often lies in providing acoordinated response that addresses both thelearning <strong>and</strong> other support needs of the individualstudents.

1 . e x e c utive summaryFigure 1 Intervention Categories covered in this ReportSchool ContextStudent ContextChange LeversAccess toSchoolSchool/LearningEnvironmentCurriculumTeachingApproachParental,Family <strong>and</strong>CommunityInvolvementBasicMaterial<strong>and</strong>PersonalSupportEngagementwith School<strong>and</strong> LearningIntensiveLearningSupportVocationalDevelopment<strong>and</strong>TransitionSupportIntevention Categories1. Holistic Schooling Approach4. Holistic Student Support8.Scholarships2.3.Tailored Appropriate(Culturally (CulturallyRelevant & Relevant &Capability CapabilityAppropriate) Appropriate)Curriculum StaffTraining5.Student &ParentalEngagement6.IntensiveLearningSupport7.School-BasedVocationalTraining &DevelopmentThe implication of this for philanthropic investors isthat well-focused investments in this area:–––––require a holistic underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the local issuesthat need to be addressed in order to achieveeffective outcomesmay involve multiple service providers (<strong>and</strong>as a result tend to require more extensive duediligence, more complex funding structures <strong>and</strong>more extensive coordination, monitoring <strong>and</strong>evaluation processes)often require higher levels of overall fundingin order to make sure that all relevant programcomponents are covered <strong>and</strong> so often involvelarger investments or collaborative fundingarrangementstend to require higher levels of supportwhere interventions are delivered in remoteareas compared to less remote areas due tothe narrower range of services <strong>and</strong> serviceproviders in those areas <strong>and</strong> the higher levels ofdisadvantage that tend to be faced thereneed to allow a reasonable timeframe for changegiven the complexity of the factors affectingeducation outcomes–in the case of school-based investments:• require the underlying organisational systemsat the school (e.g. school management<strong>and</strong> culture, staff recruitment <strong>and</strong> training,curriculum planning <strong>and</strong> student disciplineprocedures etc.) to support the delivery of theprograms being funded – the alignment of suchsystems, as well as the organisational structure<strong>and</strong> staffing of the school, with programdelivery is critical to ensure that such programsare sustainable, rather than dependent onthe principal <strong>and</strong> staff who are present at theschool at the time of investment• need to take into account taxation structuresthat currently limit the capacity of investors toaccess Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR) basedtax deductions.This Report does not provide specificrecommendations to philanthropic investorsregarding which programs they should fund. TheReport has been structured to provide investorswith useful background information to help them tounderst<strong>and</strong> the issues associated with Indigenouseducation <strong>and</strong> conceptual frameworks to help themidentify <strong>and</strong> assess potential investment options.

2. IntroductionThis section of the Report provides an overviewof the objectives of this Report <strong>and</strong> themethodology used to prepare it.1 0

2 . i n t r o d u c t i o n2.1 Purpose of this Report2.2 Scope of this ReportAlthough there is significant interestamong the philanthropic sector inIndigenous issues, investors often donot invest in the area:‘because they lack the expertise <strong>and</strong> knowledge to grantwell in a complex sector <strong>and</strong> some labour undermisconceptions about working with Indigenous causes.’ 6This Report seeks to provide insight into the rolethat the philanthropic sector can play to assist inimproving the education outcomes of Indigenousyoung people in Australia. It is also intended to bea useful tool for practitioners in the not-forprofit<strong>and</strong> government sectors with an interest inIndigenous education.The Report does not provide specificrecommendations to philanthropic investors interms of which programs they should fund. Instead,the Report has been structured to provide investorswith useful background information to help themto underst<strong>and</strong> the challenges <strong>and</strong> opportunitiesassociated with improving primary <strong>and</strong> secondarylevel Indigenous education outcomes. It also seeksto provide investors with conceptual frameworksto help them to identify <strong>and</strong> independently assesspotential investment options.The area of education is broad <strong>and</strong> the issuesaffecting the effectiveness of Indigenous educationare complex. For that reason this Report focuses onthe specific challenges <strong>and</strong> opportunities relatingto primary <strong>and</strong> secondary school level education(Years 1 to 12).This Report looks at:– Indigenous education Outcomes – it providesan overview of the state of Indigenous primary<strong>and</strong> secondary education outcomes in Australia<strong>and</strong> the impact that they have on the capacityof Indigenous students to access post-secondaryqualifications <strong>and</strong> employment opportunities– Contributing Factors – it identifies the underlyingfactors that contribute to those outcomesincluding the Social/Community, <strong>and</strong> HomeContexts in which Indigenous students live, theSchool Context in which they participate <strong>and</strong> theirown personal life experience (referred to in theReport as Student Context)– Interventions – it discusses some of theapproaches that are being taken to address thosefactors <strong>and</strong> identifies a series of InterventionCategories that are suited to philanthropicinvestment on the basis that they either augmentor complement existing government fundingor provide an opportunity for the philanthropicsector to invest in more innovative responses– Key Success Factors – it identifies the Key SuccessFactors (KSFs) relating to program design <strong>and</strong>implementation that apply to each of theidentified Intervention Categories.The Report focuses on interventions that are relatedto the School <strong>and</strong> Student Context, in particular, theway in which schooling is delivered, the experiencethat students have of school <strong>and</strong> their capacity toaccess <strong>and</strong> engage in school <strong>and</strong> to learn. The Reportdoes not investigate interventions that seek toaddress broader Social/Community or Home-basedissues affecting the capacity of Indigenous studentsto access or to engage in education <strong>and</strong> to learn. Italso does not cover government-funded programs.<strong>Primary</strong> <strong>and</strong> secondary education is obviously onlyone element of a broader education system thatstarts with early childhood development <strong>and</strong> pre-6 Scaife W. Challenges in Indigenous philanthropy: Reporting Australiangrantmakers’ perspectives. Australian Journal of Social Issues 2006,p.18. (Scaife 2006)1 1

2 . i n t r o d u c t i o n2.3 Who will find this Reportuseful <strong>and</strong> how?primary schooling <strong>and</strong> extends through to vocational<strong>and</strong> tertiary education <strong>and</strong> the transition from schoolto post-school employment. This Report does notdeal with those areas, nor does it deal with the areaof parental or adult education which is also relevantwhen considering Indigenous education outcomes.In choosing to focus on Years 1 to 12 education weare not seeking to downgrade the importance ofthose other areas, which clearly play an importantrole in Indigenous education <strong>and</strong> the translation ofeducation outcomes into labour force participation<strong>and</strong> employment. Indeed, each of those areas could,in themselves, be the subject of a separate reportsuch as this.The decision to focus on school-based education hasbeen taken as a starting point from which to buildan underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the underlying issues relatingto Indigenous education <strong>and</strong> some of the approachesthat can be taken to address them.Although the Report references some of theapproaches that are being undertaken bygovernment in this area it is not intended to(<strong>and</strong> does not) provide a detailed discussion orassessment of government policy in this area.Throughout this Report the term ‘Indigenous’ isused to refer to people identifying themselves asAustralian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er.This Report has been written predominately toinform philanthropic investors. As noted above, it isalso intended to provide a guide for practitioners inthe not-for-profit <strong>and</strong> government sectors with aninterest in Indigenous education.Figure.2 What this Report is designed to help you doUnderst<strong>and</strong> the Social ContextSection 3Underst<strong>and</strong> the Target Issues – Indigenous <strong>Education</strong> OutcomesSection 4Underst<strong>and</strong> the Factors Contributing to those OutcomesSection 5Underst<strong>and</strong> Available Intervention OptionsSection 6 <strong>and</strong> 7Underst<strong>and</strong> the Key Success Factors for those InterventionsSection 6 <strong>and</strong> 7In particular, the Report has been designed to helpphilanthropic investors to:– build an underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the issues surroundingIndigenous education in terms of the pooroutcomes that are being achieved <strong>and</strong> the factorscontributing to these outcomes (Sections 4 <strong>and</strong> 5)– identify the types of intervention that they caninvest in to address these issues (Section 6)– identify Key Success Factors that they can use toassess specific programs that they identify forpotential investment (Section 6).The case studies that are set out in Section 6 areprovided by way of example only. The programsset out in these case studies have not beenindependently reviewed or audited. Their inclusionin the Report should not, therefore, be seen as arecommendation for funding. As a matter of goodpractice philanthropic investors interested in fundinginterventions such as those identified in Section6 should ensure they undertake appropriate duediligence prior to investment to make sure that theprograms they invest in align with their fundingstrategy <strong>and</strong> meet appropriate investment criteria.1 2

2 . i n t r o d u c t i o n2.4 Methodology used to preparethis ReportThe preparation of this Report has involved five stages:Stage 1 – Literature reviewA detailed literature review was undertaken <strong>and</strong> interviews were conducted withsubject matter experts to:–––underst<strong>and</strong> the state of Indigenous education outcomes <strong>and</strong> collect backgrounddataidentify the factors contributing to these outcomesidentify the types of intervention that are effective in addressing these factors.Stage 2 – Program/response identificationA program review was conducted to identify examples of programs applying thesetypes of intervention <strong>and</strong> the service providers delivering them.This involved consultations with subject matter experts, internet-based research,a review of recommendations in research <strong>and</strong> policy papers, contact withCommonwealth, State <strong>and</strong> Territory <strong>Education</strong> Departments <strong>and</strong> Indigenousorganisations, as well as a range of philanthropic foundations that fund in this area.Stage 3 – Program/response investigationInterviews were then used to build an underst<strong>and</strong>ing of each of the aboveIntervention Categories <strong>and</strong> to identify Key Success Factors associated with thedelivery of higher impact programs <strong>and</strong> responses.The case studies provided in Section 6 are based on some of the programs that wereinvestigated. As noted above, the case studies in Section 6 are provided by wayof example only. Their inclusion in the Report should not, therefore, be seen as arecommendation for funding.Stage 4 – Framework development <strong>and</strong> draft report preparationThe information collected in Stages 1 to 3 was then used to develop the conceptual<strong>and</strong> intervention frameworks set out in this Report <strong>and</strong> a draft report was prepared.Stage 5 – Peer review <strong>and</strong> Report finalisationThe draft report was then reviewed by a panel of subject matter experts. Thefeedback <strong>and</strong> views of the Review Panel were used to inform the structure <strong>and</strong>content of the Final Report.1 3

3. BackgroundThis section sets the context for the Report. It looks at thepurpose of education <strong>and</strong> provides an overview of theAustralian education system <strong>and</strong> the Indigenous studentpopulation. It also provides a snapshot of the approachesthat government has adopted to address disparities inIndigenous versus non-Indigenous education outcomes.1 4

Bac kg ro u n dIssues relating to child development <strong>and</strong> educationIndigenous Australians continue to experience10 SCRGSP 2007, p.7.poorer outcomes than non-Indigenous Australiansacross most social <strong>and</strong> economic parameters. Onaverage Indigenous people live 17 years less than thenon-Indigenous population, their health is generallypoorer <strong>and</strong> they are approximately three times morehave been identified as key areas for strategicaction within this framework. <strong>Improved</strong> educationoutcomes are specifically identified in the frameworkas playing a key role in improving socio-economicstatus, health, wellbeing <strong>and</strong> social cohesion. 10likely to be unemployed. When they are employedtheir incomes are likely to be lower <strong>and</strong> they aremore likely to live in communities that are subject tosocial dysfunction. 7The Commonwealth Government has adopted astrategic framework through which to underst<strong>and</strong>,address <strong>and</strong> report on issues of Indigenousdisadvantage. 8 This framework identifies a range ofheadline indicators in relation to the state (relativedisadvantage) of Indigenous people <strong>and</strong> identifiesseven focus areas for strategic action.Figure 3 Commonwealth Government’s strategic framework for addressing Indigenous disadvantage 9Key objectivesCurriculumSafe, healthy <strong>and</strong> supportivefamily environments with strongcommunities <strong>and</strong> cultural identityPositive child development<strong>and</strong> prevention of violence,crime <strong>and</strong> self-harm<strong>Improved</strong> wealth creation <strong>and</strong>economic sustainability forindividuals, families <strong>and</strong> communitiesHeadline indicators– Life expectancy– Disability <strong>and</strong> chronic disease– Years 10 <strong>and</strong> 12 school retention<strong>and</strong> attainment– Post-secondary educationparticipation <strong>and</strong> attainment– Suicide <strong>and</strong> self-harm– Substantiated child abuse<strong>and</strong> neglect– Family <strong>and</strong> community violence– Deaths from homicide <strong>and</strong>hospitalisations for assault– Imprisonment <strong>and</strong> juvenile– Labour force participation<strong>and</strong> unemployment– Household <strong>and</strong> individual income– Home ownershipdetention ratesStrategic areas for actionEarly child Early school PositiveFunctionalEconomicdevelopment engagement &SubstanceEffectivechildhood <strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> resilientparticipation<strong>and</strong> growth performanceuse <strong>and</strong>environmentaltransition tofamilies <strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong>(prenatal – (preschool –misusehealth systemsadulthoodcommunitiesdevelopment3 years)Year 3)Directly education related7 SCRGSP Overview 2007, pp.1–55; ABS 4704.0.8 SCRGSP 2007, pp.7–9.9Ibid.1 5

Bac kg ro u n d3.1 The objectives ofeducation3.2 The Australianeducation systemDefined in its broadest terms, education is theprovision of formal or informal instruction to developskills <strong>and</strong> to acquire knowledge, underst<strong>and</strong>ing,values <strong>and</strong> attitudes that will allow students tooperate effectively in society <strong>and</strong> to succeed in lifein personal, social <strong>and</strong> economic terms. 11An effective school education system supportsstudent development across a range of skill areas.It contributes to: 12––––––Academic attainment – based on the acquisitionof academic skills <strong>and</strong> qualifications thatdemonstrate individual ability <strong>and</strong> provide aplatform for further education, vocational training<strong>and</strong> employmentVocational preparation – based on theidentification of vocational interests <strong>and</strong> skillsthat prepare individuals for employmentSocial skills – based on the development ofbehavioural management, communication<strong>and</strong> interpersonal skills that allow individualsto interact with other people <strong>and</strong> to buildfriendships <strong>and</strong> personal relationshipsEngagement as a citizen – based on anunderst<strong>and</strong>ing of individual rights <strong>and</strong>responsibilities, social institutions <strong>and</strong> valuesEmotional <strong>and</strong> spiritual wellbeing – based on thedevelopment of a sense of personal <strong>and</strong> culturalidentity <strong>and</strong> self-worthPhysical health – based on an underst<strong>and</strong>ingof how to manage personal <strong>and</strong> family health,maintain a healthy environment <strong>and</strong> accessavailable services to meet health needs.Under the Australian Constitution matters relatingto education are the responsibility of the State<strong>and</strong> Territory Governments. In practice, policy <strong>and</strong>funding responsibility for education is sharedbetween the State, Territory <strong>and</strong> CommonwealthGovernments. 13<strong>Education</strong> policy is coordinated at a national levelthrough the Ministerial Council on <strong>Education</strong>,Employment, Training <strong>and</strong> Youth Affairs (MCEETYA).Current policy is based on the goals <strong>and</strong> objectivesset out in the National Goals for Schooling for the21st Century that was agreed by the MinisterialCouncil in 1999. Vocational <strong>and</strong> technical educationis specifically coordinated through the AustralianNational Training Authority Ministerial Council(ANTA MINCO). 14Responsibility for education funding is split, withthe State <strong>and</strong> Territory Governments having primaryresponsibility for funding government schoolsincluding preschool, primary <strong>and</strong> secondary school<strong>and</strong> vocational training, <strong>and</strong> the CommonwealthGovernment having primary responsibility forfunding non-government/independent schools,registered training providers <strong>and</strong> tertiaryeducation. 15In most Australian States <strong>and</strong> Territories schoolingis compulsory for children aged between six <strong>and</strong> 15years 16 with compulsory education ending in Year9 or Year 10. Preschool attendance is not currentlycompulsory. 17There are some minor variations in the structureof the schooling systems across the differentStates <strong>and</strong> Territories in terms of the delineationbetween primary <strong>and</strong> secondary schooling <strong>and</strong> theterminology that is used to refer to different studentgroups (particularly in the preschool, middle school<strong>and</strong> senior school years). However, the underlyingeducation system is similar.13 National Report to Parliament on Indigenous <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong>Training 2004. Department of <strong>Education</strong>, Science <strong>and</strong> Training.Commonwealth of Australia, 2004, pp.1–3. (DEST 2004)14 Ibid., pp.2–3.11 Council for the Australian Federation. The Future of Schooling inAustralia. Federalist Paper 2. April 2007, p.27. (CAF 2007)12 Ibid.; Steering Committee for the Review of Government ServiceProvision. Report on Government Services 2007, IndigenousCompendium. Canberra: Productivity Commission SCRGSP, 2007,p.22. (SCRGSP Compendium 2007)15 Ibid.16 ACT, QLD, NSW, VIC, NT 6–15 years, TAS <strong>and</strong> SA 6–16 years, WA6–17 years.17 SCRGSP 2007, p.6.3. The term preschool has been used to refer topreschool in ACT <strong>and</strong> NSW or kindergarten in QLD, VIC, TAS, SA <strong>and</strong>WA <strong>and</strong> transition in NT.1 6

Figure 4 Australian schools profile 18In 2006 there were9,612 schoolsoperating in Australia,the majority of whichwere governmentoperatedschools(72%).Chart 1 Australian schools breakdownIndependent 1,00710%Catholic 1,70318%Chart 2 Breakdown of schools by studentgroup coverageCombined <strong>Primary</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Secondary</strong> 1,18113%<strong>Secondary</strong> 1,47816%Government 6,90272%<strong>Primary</strong> 6,55871%Figure 5 <strong>Education</strong> system structure by jurisdiction 19Year Level ACT NSW VIC TAS QLD SA WA NTPre-Year 1 Kindergarten Kindergarten Prep.School Prep.School Preparatory Reception Pre-<strong>Primary</strong> TransitionYear 1Curriculum<strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Primary</strong> <strong>Primary</strong>School School School School School School School SchoolYear 2Year 3Year 4Year 5Year 6Year 7 High School High School <strong>Secondary</strong> High School MiddleSchoolSchoolYear 8 High School <strong>Secondary</strong>/ High SchoolHigh SchoolYear 9Year 10High SchoolYear 11 College CollegeYear 12Preschool <strong>Primary</strong> school <strong>Secondary</strong> school18 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Schools Report. Cat. no. 4221.0.Canberra: ABS, 2006, pp.3, 7–8, 16. (ABS 4221.0)19 DEST 2004, p.30.1 7

Bac kg ro u n dAll States <strong>and</strong> Territories provide basic primary <strong>and</strong>secondary education. Academic <strong>and</strong> vocationalstreams are available in all jurisdictions. Althoughcurriculum components are similar, they are notcurrently st<strong>and</strong>ardised, <strong>and</strong> so there is somevariation from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, <strong>and</strong> schoolto school. Differing tertiary entrance assessmentsystems are applied; however, cross-jurisdictionalrecognition is given to the different systems.Post-compulsory education is regulated within theAustralian Qualifications Framework (AQF) thatprovides a system of national qualifications inschools, vocational education <strong>and</strong> training <strong>and</strong> thehigher education sector.Tertiary education is provided in all States <strong>and</strong>Territories as is Vocational <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> Training(VET) or Technical <strong>and</strong> Further <strong>Education</strong> (TAFE).VET <strong>and</strong> TAFE training options can be accessedthrough school-based programs or as a form of postsecondaryeducation. They typically target tradebasedcareers that do not require a university degree.Typically VET or TAFE courses take two to three yearsto complete.Tertiary <strong>and</strong> vocational qualifications are transferablebetween all States <strong>and</strong> Territories.Figure 6 <strong>Education</strong>al pathways map 20School-BasedPathwaysNon School-BasedPathwaysSchool-BasedAcademic StreamSchool-BasedVET StreamExtensionLearningSpecial NeedsSupportAlternativeLearningProgramsAlternativeLearningProgramsSt<strong>and</strong>ard schoolcertificate curriculumor equivalentACT – Year 12 CertificateQLD – Senior CertificateNSW – Higher SchoolCertificateVIC – VictorianCertificate of <strong>Education</strong>TAS – TasmanianCertificate of <strong>Education</strong>SA – South AustralianCertificate of <strong>Education</strong>WA – Western AustralianCertificate of <strong>Education</strong>NT – Northern TerritoryCertificate of <strong>Education</strong>Vocational educationcertificate, applied learning<strong>and</strong> industry internshipsQLD, VIC <strong>and</strong> SA –accredited VET from Year 10<strong>and</strong> from Year 9 in WADualTargetedCurriculum – Curriculum –offered as offereda parallel throughtrack to the specialistacademic schools (e.g.stream within technicala school colleges)Extensionlearningprogramsprovided togifted studentsSpecialist teachingsupport providedto high-need orat-risk students(e.g. Aboriginal<strong>Education</strong> Workers,Youth Counsellors)1:1 servicesprovided to highneedor at-riskgroups(e.g. mentoring,case management,individual learningpathways etc.)Specialistprograms thatprovide remedialeducationsupport toat-risk <strong>and</strong>gifted studentsSpecialist programsthat provide supportto disengaged or at-riskstudents to re-engagestudents in school,provide alternativeeducation in a nonschoolenvironment,support transitionsfrom school to workPathway to connectto further educationor employmentPathway toconnect tofurthereducation oremploymentPathway toconnect tofurthervocationaltraining oremploymentPathway toreconnectwithschoolingPathwayto enteremployment20 Social Ventures Australia. Big Picture Company Australia: BriefingPaper, January 2007, p.13. (SVA 2007)1 8

3.3 The Indigenous student population3.3.1 Overall Indigenous population –a contextual overviewCensus data in 2006 indicates that Australia hasan estimated Indigenous population of 517,200people, equating to approximately 2.5% of the totalAustralian population. 21The Indigenous population is growing atapproximately 2% per annum, twice the rate of thegeneral population. 22Figure 7 Indigenous population by State <strong>and</strong> Territory 23WA 15% NT 13%TAS 3%SA 5%VIC 6%QLD 28%ACT 1%NSW 29%Indigenous Population NT QLD NSW ACT VIC SA TAS WAApproximate Population 67,236 144,816 149,988 5,172 31,032 25,860 15,516 77,580% Total Indigenous Population 13% 28% 29% 1% 6% 5% 3% 15%% State or Territory Population 31.6% 3.6% 2.2% 1.2% 0.6% 1.7% 3.4% 3.8%Figure 8 Indigenous population distribution based onThe majority of Indigenous people in Australia livest<strong>and</strong>ard remoteness scales 25in major cities <strong>and</strong> urban centres (31%). The balanceof the Indigenous population is reasonably evenlydistributed across regional <strong>and</strong> remote areas. JustRemote/Very remoteMajor citiesunder a quarter (24%) of the Indigenous populationlives in remote or very remote locations. 2424%31%Outer regionalInner regional23%22%21 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population Distribution, Aboriginal<strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er Australians. Cat. no. 4705.0. Canberra: ABS,2006. (ABS 4705.0)22 Ministerial Council for <strong>Education</strong>, Employment, Training <strong>and</strong>Youth Affairs AESOC Senior Officials Working Party on Indigenous<strong>Education</strong>. Australian Directions in Indigenous <strong>Education</strong> 2005–2008MCEETYA, 2006, pp.11, 15. (MCEETYA 2006)23 ABS 4705.0.24 Ibid. The remoteness structure shown here is based on the AustralianSt<strong>and</strong>ard Geographical Classification (ASGC) used by the ABS.There are five major categories of Remoteness Area: Major Cities ofAustralia, Inner Regional Australia, Outer Regional Australia, RemoteAustralia <strong>and</strong> Very Remote Australia, together with a residualMigratory category.25 Ibid.1 9

Bac kg ro u n dFigure 9 Comparison Indigenous <strong>and</strong> non-Indigenous population age profile 26Estimated resident population by ageMalesAge groupsFemales75+70–7465–6960–6455–5950–5445–4940–4435–3930–3425–2920–2415–1910–145–90–43.3.2 Student population profileTwenty-seven per cent of the total Indigenouspopulation (140,381 people) were enrolled as fulltimestudents in 2006, making up approximately 4%of the total full-time student population. 29The majority of those Indigenous students (64.8%)were enrolled in primary school (compared to 57.2%for the non-Indigenous student population). 30Over 90% of Indigenous students were aged 15years or less (15 years of age being the age at whichcompulsory schooling ends for most students inYear 9 or 10). 31 The bias in the age of the Indigenousstudent population reflects the higher rate at whichIndigenous students drop out of school following thecompletion of compulsory schooling in Year 9 or 10. 32services required to meet the needs of this group. 28 15 yearsFigure 10 Indigenous secondary student population 337 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 % 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 719 years <strong>and</strong> over12 years <strong>and</strong> underIndigenousNon-Indigenous31818 years5,66613 yearsThe Indigenous population overall is younger than the non-Indigenous population. 72311,50417 yearsThe median age of the Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er population (21 years)3,560is considerably lower than that of the non-Indigenous Australian population (36years). Almost half of the Indigenous population is approaching or of school age. 2716 years14 yearsThe lower age profile of the Indigenous population has implications for the6,69011,225proportion of the population that is (or should be) at school <strong>and</strong> the support9,683Figure 9 Indigenous secondary student population 34Indigenous Student 12 Years 13 years 14 Years 15 Years 16 Years 17 Years 18 Years 19 Years Total % TotalPopulation <strong>and</strong> under <strong>and</strong> over<strong>Primary</strong> School 90,396 598 18 – – – – – 91,012 64.8%<strong>Secondary</strong> School 5,666 11,504 11,225 9,683 6,690 3,560 723 318 49,369 35.2%Total 96,062 12,102 11,243 9,683 6,690 3,560 723 318 140,381 100%Percentage of Population 68.4% 8.6% 8.0% 6.9% 4.8% 2.6% 0.5% 0.2% 100% –26 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population Characteristics ofAboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er Australians. Cat. no. 4713.0.Canberra: ABS, 2001. (ABS 4713.0)27 ABS 4713.0; ABS 4704.0; Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Ageing.Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Ageing Factbook 2006. (DHA 2006)28 MCEETYA 2006, p.11.29 ABS 4221.0, p.18.30 Ibid., p.17.31 ABS 4221.0, p.17.32 SCRGSP 2007, pp.7.22–7.23.33 ABS 4221.0, p.17.2 0

Figure 11 Indigenous versus non-Indigenous secondary school student population profile 341412108611.811.0School context9.46.868.6% Drop instudent numbers300250200150161.1263.0 260.8 258.4228.026.7% Drop192.74204.63.72.110050018.5Year 7Year 8Year 9Year 10Year 11Year 12 UngradedYear 7Year 8Year 9Year 10Year 11Year 12 UngradedIndigenousNon-IndigenousThe majority of Indigenous students are enrolled ingovernment schools. 35In most cases Indigenous students make up onlya very small percentage of their school’s studentbase (which is not unexpected given the size ofthe overall Indigenous population). Approximatelythree quarters (74.9%) of Australian schools provideeducation to one or more Indigenous students <strong>and</strong>in over half of those schools Indigenous studentsrepresent 5% or less of the school population. 36The number of Indigenous staff operating in schoolsis also low. Although the number of Indigenousteachers is increasing, the proportion of Indigenousteachers <strong>and</strong> staff working in individual schools isusually smaller than the proportion of Indigenousstudents. 3734 Ibid.35 MCEETYA 2006, p.15; SRCGSP Compendium 2007, p.24.36 SCRGSP 2007, p.7.25.37 Ibid., p.32.2 1

Bac kg ro u n d3.4 Government-based Indigenous-specificeducation initiativesAustralian Governments have recognised the needto address disparities between Indigenous <strong>and</strong> non-Indigenous students’ education outcomes. 38Specific government policy objectives in relation toIndigenous education are set out in the NationalAboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er <strong>Education</strong>Policy (AEP). This Policy has been endorsed by theCommonwealth, State <strong>and</strong> Territory Governments<strong>and</strong> forms the foundation of all governmentIndigenous education programs. It sets out 21long-term national goals for the improvementof Indigenous education. These goals have beenlegislated for in the Indigenous <strong>Education</strong> (TargetedAssistance) Act 2000. In particular, the AEP aims tomake the level of education access, participation<strong>and</strong> outcomes for Indigenous people equal to thatof other Australians. 39National Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er <strong>Education</strong> Policy Goals 40Involvement of Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er people in educationaldecision-making1. To establish effective arrangements for the participation of Aboriginal<strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er parents <strong>and</strong> community members in decisionsregarding the planning, delivery <strong>and</strong> evaluation of preschool, primary <strong>and</strong>secondary education services for their children.2. To increase the number of Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er peopleemployed as educational administrators, teachers, curriculum advisers,teachers assistants, home–school liaison officers <strong>and</strong> other educationworkers, including community people engaged in teaching Aboriginal<strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er culture, history <strong>and</strong> contemporary society, <strong>and</strong>Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er languages.3. To establish effective arrangements for the participation of Aboriginal<strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er students <strong>and</strong> community members in decisionsregarding the planning, delivery <strong>and</strong> evaluation of post-school educationservices, including technical <strong>and</strong> further education colleges <strong>and</strong> highereducation institutions.4. To increase the number of Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er peopleemployed as administrators, teachers, researchers <strong>and</strong> student servicesofficers in technical <strong>and</strong> further education colleges <strong>and</strong> higher educationinstitutions.5. To provide education <strong>and</strong> training services to develop the skills ofAboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er people to participate in educationaldecision-making.6. To develop arrangements for the provisions of independent advice fromAboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er communities regarding educationaldecisions at regional, State, Territory <strong>and</strong> National levels.Equality of access to education services7. To ensure that Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er children of pre-primaryschool age have access to preschool services on a basis comparable to thatavailable to other Australian children of the same age.8. To ensure that all Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er children have localaccess to primary <strong>and</strong> secondary schooling.9. To ensure equitable access of Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>erpeople to post-compulsory secondary schooling, to technical <strong>and</strong> furthereducation, <strong>and</strong> to higher education.38 CAF 2007, p.23; MCEEYTA 2006, p.4.39 DEST 2004, pp.2–3 <strong>and</strong> 149–150.40 Ibid., pp.149–150.2 2

Equity of educational participation10. To achieve the participation of Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er childrenin preschool education for a period similar to that for other Australianchildren.11. To achieve the participation of all Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>erchildren in compulsory schooling.12. To achieve the participation of Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er peoplein post-secondary education, in technical <strong>and</strong> further education, <strong>and</strong> inhigher education, at rates commensurate with those of other Australians inthose sectors.Equitable <strong>and</strong> appropriate educational outcomes13. To provide adequate preparation of Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>erchildren through preschool education for the schooling years ahead.14. To enable Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er attainment of skills to thesame st<strong>and</strong>ard as other Australian students throughout the compulsoryschooling years.15. To enable Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er students to attain thesuccessful completion of Year 12 or equivalent at the same rates as forother Australian students.16. To enable Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er students to attain the samegraduation rates from award courses in technical <strong>and</strong> further education,<strong>and</strong> in higher education, as other Australians.17. To develop programs to support the maintenance <strong>and</strong> continued use ofAboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er languages.18. To provide community education services which enable Aboriginal<strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er people to develop the skills to manage thedevelopment of their communities.19. To enable the attainment of proficiency in the English language <strong>and</strong>numeracy competencies by Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er adults withlimited or no educational experience.Pursuant to these goals Commonwealth <strong>and</strong> State<strong>and</strong> Territory Government policies have sought toimprove/strengthen:– preschool access <strong>and</strong> attendance as aprecondition of ‘school readiness’– school attendance– the quality of school leadership <strong>and</strong> teaching– the design <strong>and</strong> delivery of culturally relevant<strong>and</strong> capability appropriate curriculum <strong>and</strong>teaching approaches– literacy <strong>and</strong> numeracy outcomes– post-school transitions into employment throughthe delivery of improved school <strong>and</strong> non-schoolbasedvocational <strong>and</strong> employment pathways– school, family <strong>and</strong> community partnershipsto support improved school attendance,engagement, retention <strong>and</strong> attainment. 41Examples of the above activities are reflected inCommonwealth Government funded initiativesunder the National Indigenous English Literacy <strong>and</strong>Numeracy Strategy (NIELNS) (e.g. Scaffolding Literacyprograms) 42 <strong>and</strong> the Indigenous <strong>Education</strong> StrategicInitiative Program (IESIP) (e.g. What Works <strong>and</strong> Dareto Lead programs) implemented under the previousCommonwealth Government. 43Ongoing commitment to those areas is reflectedat a national level in the recommendations to theMinisterial Council on <strong>Education</strong>, Employment,Training <strong>and</strong> Youth Affairs (MCEETYA) for the 2005–2008 quadrennium endorsed by the MinisterialCouncil. 44 These recommendations identified sixareas for focus in Indigenous education.20. To enable Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er students at all levels ofeducation to have an appreciation of their history, culture <strong>and</strong> identity.21. To provide all Australian students with an underst<strong>and</strong>ing of <strong>and</strong> respect forAboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er traditional <strong>and</strong> contemporary cultures.41 MCEETYA 2006; National Indigenous <strong>Education</strong> <strong>and</strong> Training Strategy2005–2008. http://www.dest.gov.au (IETS); National IndigenousEnglish Literacy <strong>and</strong> Numeracy Strategy. http://www.dest.gov.au(NIELNS)42 NIELNS43 IETS44 MCEETYA 2006, pp.5–10. Cross-government endorsement of theprinciples outlined in the above document means that they areunlikely to change as a result of the recent transition in FederalGovernment. It is not yet clear whether the approach to how thoseareas are addressed through Federal Government policy, funding<strong>and</strong> coordination mechanisms will change.2 3

Bac kg ro u n dTable 1 – Australian Directions in Indigenous <strong>Education</strong> 2005–2008 45Focus AreasIdentified PrioritiesEarly childhood– Provide all Indigenous children with access to two years of high-quality earlyeducationchildhood education prior to formal schooling– Develop <strong>and</strong> implement educational programs that respect <strong>and</strong> valueIndigenous culture, languages (including Aboriginal English) <strong>and</strong> contexts;explicitly teach st<strong>and</strong>ard Australian English <strong>and</strong> prepare Indigenous childrenfor formal schooling– Provide opportunities for Indigenous parents <strong>and</strong> care givers to develop skillsto support the development of their children’s literacy skills <strong>and</strong> to allowparents <strong>and</strong> care givers to play an active role in the education of their childrenSchool <strong>and</strong> community – Promote the value of formal educationeducational partnerships – Encourage the development of school, parent <strong>and</strong> community partnershipsthat encourage Indigenous parents <strong>and</strong> communities to work with schools toaddress local attendance, retention <strong>and</strong> attainment issues– Increase parent <strong>and</strong> community involvement in the design <strong>and</strong> delivery ofIndigenous schooling (particularly in schools with significant Indigenousstudent cohorts or local Indigenous communities)Schooling curriculum – Tailor curriculum to meet student requirements (i.e. through the design <strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> approachdelivery of culturally relevant <strong>and</strong> capability appropriate curricula) whilemaintaining high educational st<strong>and</strong>ardsSchool leadership – Include learning outcomes for Indigenous students as a key part of theaccountability framework for school principals <strong>and</strong> teaching staff– Review <strong>and</strong> improve incentives that attract <strong>and</strong> retain high-quality principalsto schools with significant Indigenous student cohorts or local Indigenouscommunities– Implement strategies that recognise high-performing schools <strong>and</strong> principals– Provide accredited school leadership <strong>and</strong> teacher-training programs thatdevelop school leadersQuality teaching – Provide accredited pre- <strong>and</strong> in-service teacher training that includes culturalawareness <strong>and</strong> specialist teaching skills tailored to Indigenous student needs(e.g. English as a Second Language)– Review <strong>and</strong> improve incentives that attract <strong>and</strong> retain high-quality teachersPathways to training, – Design <strong>and</strong> deliver mentoring, counselling <strong>and</strong> work-readiness programs thatemployment <strong>and</strong>provide culturally inclusive <strong>and</strong> intensive vocational development support inhigher educationsecondary school to assist Indigenous students to transition from school intopost-school education, training or employment– Improve vocational learning opportunities for Indigenous students from Year10 onwards– Exp<strong>and</strong> trade-based training– Strengthen school to tertiary education support programs45 Ibid., pp.5-10.2 4

4. Indigenous educationoutcomesThis section looks at the status of Indigenous<strong>Education</strong> Outcomes. It outlines the performance ofIndigenous students against a range of educationoutcomes including school attendance, retention,performance, post-school qualifications, labourforce participation <strong>and</strong> employment, socioeconomicstatus <strong>and</strong> individual wellbeing.2 5

i n d i g e n o u s e d u c at i o n o utco m e s‘While Indigenous student outcomes have improved incrementallyover recent decades, marked disparities continue to exist betweenIndigenous <strong>and</strong> non-Indigenous student outcomes. Poor results limitthe post-school options <strong>and</strong> life choices of students, perpetuatingintergenerational cycles of social <strong>and</strong> economic disadvantage.’ 46The outcomes of effective education can beconsidered at multiple levels. At the most basiclevel education engages students <strong>and</strong> encouragesparticipation in learning, which is reflected inschool attendance <strong>and</strong> retention. At the next levelit promotes the development of skills <strong>and</strong> theacquisition of knowledge, which is reflected instudent achievement <strong>and</strong> performance. Studentperformance in turn influences the capacity ofstudents to access post-school qualifications. Thesequalifications, combined with school performance,influence labour force participation <strong>and</strong>employment, which in turn influence socio-economicstatus <strong>and</strong> individual health <strong>and</strong> wellbeing.Figure 12 <strong>Education</strong> outcomes – conceptual frameworkOutcomesSixth OrderFifth OrderCurriculumIndividualWellbeingSocio-economicStatusFourth OrderLabour Force Participation<strong>and</strong> EmploymentThird OrderPost-School QualificationSecond OrderSchool Performance / AchievementFirst OrderSchool AttendanceSchool Retention46 CAF 2007, p.23.2 6

The achievement of higher order outcomes isdependent on the achievement of the lower orderoutcomes on which they are built.It is important to acknowledge that there has beenimprovement in Indigenous education outcomesover the last decade. Indigenous participation ineducation has increased across all education levels(schools, universities, <strong>and</strong> vocational education<strong>and</strong> training) as has the number of studentsgraduating from Year 12 <strong>and</strong> attaining postschoolqualifications. 47 However, this progresshas been slow <strong>and</strong> significant disparities betweenthe education outcomes of Indigenous <strong>and</strong> non-Indigenous students continue to exist. 48In Australia today Indigenous students at all levelscontinue to experience worse education outcomesthan non-Indigenous students. 49 Indigenousstudents demonstrate lower school attendance,retention <strong>and</strong> achievement than non-Indigenousstudents across all age groups <strong>and</strong> all States <strong>and</strong>Territories. 50 Post-school qualification, labourforce participation <strong>and</strong> employment rates are alsolower. 51 Indigenous employees are more likelyto be employed in lower skilled occupations thannon-Indigenous employees, Indigenous employees’incomes are likely to be lower 52 , their health isgenerally poorer, their life expectancy is lower <strong>and</strong>they are more likely to live in communities that aresubject to social dysfunction. 53Indigenous children in remote areas tend to haveeven lower rates of school attendance, retention <strong>and</strong>achievement, <strong>and</strong> lower post-school outcomes thanthose in non-remote areas. 54Indigenous Australians:– are less likely to get a preschool education– are well behind in literacy <strong>and</strong> numeracy skills development beforethey leave primary school– have less access to secondary school in the communities in whichthey live– are absent from school two to three times more often thanother students– leave school much younger– are less than half as likely to go through to Year 12– are far more likely to be doing bridging <strong>and</strong> basic entry programs inuniversities <strong>and</strong> vocational education <strong>and</strong> training institutions– obtain fewer <strong>and</strong> lower-level education qualifications– are far less likely to get a job, even when they have the samequalifications as others– earn less income– have poorer housing– experience more <strong>and</strong> graver health problems– have higher mortality rates than other AustraliansThe need to address the gap between Indigenous<strong>and</strong> non-Indigenous outcomes across each of theabove areas has been recognised in the COAGNational Reform Agenda <strong>and</strong> the MCEETYAquadrennial statement on National Directions inIndigenous <strong>Education</strong> 2005–2008. 56Overview of the current state of Indigenous education outcomes 55 2 747 ABS 4704.0; ABS 4221.0; MCEETYA, 2006, pp.4, 11.48 MCEETYA 2006, p.11.49 SCRGSP Overview 2007, p.4.50 SCRGSP 2007, pp.13–14.51 Ibid., pp.14–16, 13.2, 13.11.52 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force Characteristics ofAboriginals <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er Australians. Cat. no. 6287.0.Canberra: ABS, 2006. (ABS 6287.0)53 SCRGSP Overview 2007, pp.12, 18–23; ABS 4704.0.Sub-sections 4.1 – 4.7 of this Report provide moreinformation in relation to the current state ofIndigenous education outcomes against eachof the key outcome areas identified in Figure12. A discussion of the factors contributing tothese outcomes is set out in Section 5. A range ofinterventions to address these issues is outlinedin Section 6.54 SCRGSP 2007, p.6.9.55 National Indigenous English Literacy <strong>and</strong> Numeracy Strategy.Supporting Statement from Indigenous Supporters of the NIELNS.http://www.dest.gov.au (NIELNS SS)56 SCRGSP 2007, p.6.3; COAG National Reform Agenda: Human Capital,Competition <strong>and</strong> Regulatory Reform, Communique 14. Canberra, July2006. (COAG 2006); MCEETYA 2006, pp.1–32.

i n d i g e n o u s e d u c at i o n o utco m e s4.1 AttendanceOutcome AreasPreschool participation(enrolment) 57Preschool attendance 58School readiness 59School participation(enrolment)School attendanceKey Performance Indicators– Indigenous children aged 3 to 5 years aremarginally less likely to be enrolled in preschool(25%) than non-Indigenous children (29%)– Preschool attendance is significantly lowerfor Indigenous children than for non-Indigenous children– Indigenous children who do attend preschool donot demonstrate the same level of literacy <strong>and</strong>numeracy skills as non-Indigenous children– School participation rates for Indigenouschildren aged 5 to 8 years (Years 1 to 3) (97%)are marginally higher than those for non-Indigenous children (94%) 60– Indigenous school participation rates throughhigher primary <strong>and</strong> secondary school are lowerthan those for non-Indigenous students 61– Indigenous participation rates drop offmuch more rapidly than non-Indigenousstudent numbers following the completion ofcompulsory schooling in Year 9 or 10 62– School attendance is lower for Indigenousstudents with Indigenous students likely tobe absent from primary <strong>and</strong> secondary schooltwo to three times more often than non-Indigenous students 63– The gap in school attendance appears early inprimary school <strong>and</strong> widens in the early yearsof secondary school 644.1.1 Preschool attendanceResearch indicates that access to early childhoodeducation has a positive impact on educationoutcomes. Children who attend preschool formore than one year show statistically significantimprovements in performance in later school yearscompared to students not attending preschool. 65Data indicates that Indigenous children aremarginally less likely to be enrolled in preschool thannon-Indigenous children. In 2005 approximately 25%of Indigenous children aged three to five years wereenrolled in preschool compared to approximately29% of non-Indigenous children. 66The ability to assess attendance – as distinct fromenrolments – on a national level is limited due toconstraints in existing data collection techniquesthat focus on enrolments rather than attendance.Where attendance data is collected, variations in theways in which absences are defined <strong>and</strong> recordedmake comprehensive analysis difficult.Although available attendance data is limited,anecdotal evidence suggests that attendance ratesfor Indigenous students enrolled in preschool aresignificantly lower than those for non-Indigenousstudents. 67The lower attendance rate, combined with the lowerenrolment rate, translates into a significant disparityin real access to early childhood education.57 SCRGSP Overview 2007, p.29.58 SCRGSP 2007, pp.6.3–6.459 MCEETYA 2006, p.18.60 SCRGSP Overview 2007, p.30.61 SCRGSP Compendium 2007, p.27.62 SCRGSP Overview 2007, p.30.63 Zubrick et al. 2006, pp.113ff; Bourke C, Rigby K, Burden J. BetterPractice in School Attendance: Improving the School Attendance ofIndigenous Students. Commonwealth Department of <strong>Education</strong>,Training <strong>and</strong> Youth Affairs, 2000, pp.1, 12. (Bourke et al. 2000)64 Bourke et al. 2000, p.13.65 SCRGSP 2007, p.6.1; Kronemann M. Universal Preschool <strong>Education</strong>for Aboriginal <strong>and</strong> Torres Strait Isl<strong>and</strong>er Children. AEU Briefing Paper2007, p.4. (Kronemann 2007a)66 SCRGSP 2007, p.6.5.67 Ibid., pp.6.3-6.4.2 8