Towards A Unified Zakat System

Towards A Unified Zakat System

Towards A Unified Zakat System

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

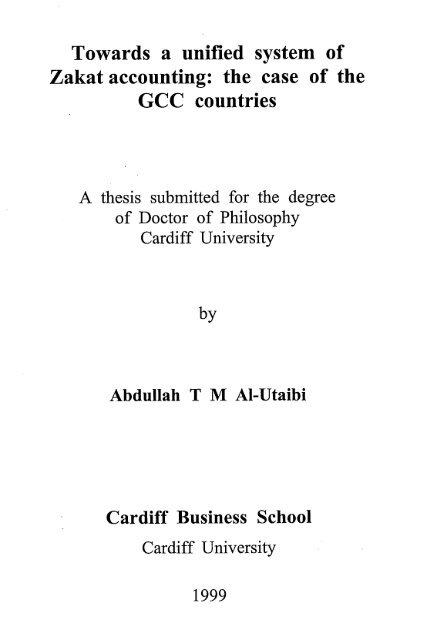

<strong>Towards</strong>a unified system of<strong>Zakat</strong> accounting:the case of theGCC countriesA thesis submitted for the degreeof Doctor of PhilosophyCardiff UniversitybyAbdullah TM Al-UtaibiCardiffBusiness SchoolCardiff University1999

DECLARATIONThis work has not previously been accepted in substance forany degree and is not being concurrently submitted incandidature for any degreeSigned----------- --------(Abdullah Al-Utaibi - student)Date ---ýý-ýLLII-I-q. T --=------STATEMENT 1This thesis is the result of my own investigations, exceptwhere otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledgedgiving explicit references. A bibliography is appended.Signed---------- - -------(Abdullah Al-Utaibi - student)Date----26-/ IL , -Lci-`1-4-------STATEMENT 2I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to beavailable for photocopy and for inter-library loan, and forthe title and summary to be made available to outsideorganisations.Signed--- ---- -- -------(Abdullah Al-Utaibi - student)41 /JT9-ýDate----2-6-------1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSIN THE NAME OF ALLAH, MOST GRACIOUS, MOST MERCIFULI AM THANKFUL TO ALMIGHTY ALLAH FOR HIS GUIDANCE AND BLESSINGON THE SUCCESS OF MY EFFORTS DURING THE COURSE OF THIS STUDY.Then I would like to express my deepest thanks to a numberof very special individuals and organisations who have madea valuable contribution to this thesis.Firstly, I owe a major debt of gratitude to my supervisorDr. Kamal Naser for his sustained interest, help as well asfriendly encouragement, during my study at the Universityof Cardiff. Secondly, special thanks and gratitude are dueto the director, deputy directors and the head ofAccounting and Finance Section, Cardiff University.My appreciation also goes to Mr. Tawfeek Al-Khyal,Mr. Saleh AlMahmoud, Ibrahim Al-Taweel, Dr. AbdulmajedAbdulgani, Dr. Yahya Younis, Ammar Al-Khshram, AhmmadAl-Sharif and khalid Al-Khateb for the generousencouragement, ideas and advice provided in the preparationof my thesis. Thanks go to all the librarians at thebusinessschool.Thirdly, I would like to emphasis my gratitude to my motherfor her love, prayers and encouragement, and to all my11

family members back home for their support, patience andunderstanding. Very special thanks are due to my belovedfamily here with me in Cardiff, to my wife, Am Abdullaziz,for her sacrifice, patience and understanding; to my sonAbdullaziz and my daughters Ohoud, Wadaha, Basimah, Rubaand Renad for not having had my full attention as well asfor the little ways in which they helped.Finally, to those individuals who have contributed to thisstudy along with whom I have inadvertently omitted mygratitude for their efforts.iii

PAGINATION ERROR INORIGINALTHESIS

AbstractThe possibility of establishing an accounting system for<strong>Zakat</strong>, one of the pillars of the Islamic faith isexamined first by investigating the relevance of thesocio-economic environment of the Gulf Co-operativeCouncil (GCC) countries to introducing a unified systemfor <strong>Zakat</strong>. Having achieved this general aim, the studyattempts, secondly, to develop an accounting systemserving the different processes of <strong>Zakat</strong> estimation,calculation, collection and distribution. Employing thefundamental principles of financial accounting, both theaims and objectives were served by designing a researchquestionnaire distributed to four groups of peopleclassified by occupation in four of the six Gulf States.These countries are Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and theUnited Arab Emirates. A sample of 159 respondents wasselected as representative of the societies of the GCCcountries.The results of the analysis revealed that the environmentof the Gulf States is prepared to adopt the relevantarrangements for a <strong>Zakat</strong> organisation. Based on theexperience of Saudi Arabia, the study reveals theproblematic issues in imposing the duty of <strong>Zakat</strong> in theother Gulf States. The study also reports that there is areal need to establish an accounting system which willrespond to the multi-functions of <strong>Zakat</strong>. Respondents wereeager for a distinctive governmental role in organisingthe whole processes, as governments have both thereligious liability and compulsory power to implement<strong>Zakat</strong> legislation. An efficient system of calculating theamount of <strong>Zakat</strong> payable to the needy requires someadjustment in financial reports and disclosure.V

ContentsPageDeclarationiDedicationiiAcknowledgementsiiiAbstractvContentsviList of tables xiiGlossary of terms xivChapteroneIntroduction1.0 Introduction 11.1 Objectives of the study 41.2 Methodology 5/1.3 Limitations of the study6Organisation of the thesis 71.4ChaptertwoGeneral background to the GCC stat es2.0 Introduction 112.1 The Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) 122.1.1 Bahrain 132.1.1.1 Economic background 142.1.1.2 Social, Cultural and political background 182.1.2 Kuwait 192.1.2.1 Economic background 202.1.2.2 Social, Cultural and political background 212.1.3 Saudi Arabia (SA) 222.1.3.1 Economic background 242.1.3.2 Social, Cultural and political background 262.1.4 The United Arab Emirates (UAE) 282.1.4.1 Economic background 282.1.4.2 Social, Cultural and political background 312.1.5 Oman 322.1.6 Qatar. -342.2 Aggregate analysis of the economicstructure of GCC countries V 352.3 Co-operation in the GCC states 422.4 An example of <strong>Zakat</strong> regulation42.5 Summary 50vi

ChapterthreePrinciples of Islamic economics3.0 Introduction 523.1 Islamic dimensions to the study 543.2 Islamic economics 593.3 Principles of unity and brotherhood 633.4 Goals of Islamic economics 643.4.1 Economic wellbeing 653.4.2 Social justice 673.4.3 Economic justice 683.4.4 Equitable distribution of income 703.4.5 Freedom of ownership and activity 723.5 Islamic prohibition of riba 743.5.1 Definition of riba and reasons forits prohibition in Islamic economics 753.5.2 Reasons behind the prohibition of riba 783.5.3 Types of riba 793.6 Islamic economics and ethics 803.7 Islam and economic problems 863.8 Economic intervention by the state 873.9 Islamic economic in practice 923.10 Summary 95Chapte r four<strong>Zakat</strong> and its position in Islam4.0 Introduction 994.1 Principles of <strong>Zakat</strong> 1014.1.1 Goals of <strong>Zakat</strong> 1034.1.1.1 Religious goals 1034.1.1.2 Social goals 1044.1.1.3 Economic goals 1044.2 Beneficiaries of <strong>Zakat</strong> 1054.3 Entities and wealth subject to <strong>Zakat</strong> 1084.3.1 Entities 1084.3.2 Wealth 1114.3.2.1 Complete ownership 1114.3.2.2 Actual growth or ability to grow 1144.3.2.3 Ownership of a specified level of wealth 1154.3.2.4 The passage of a year 1164.4 <strong>Zakat</strong> on capital and its proceeds 1164.4.1 <strong>Zakat</strong> on animal wealth 116vi'

4.4.1.1 <strong>Zakat</strong> on pastoral animals 1174.4.1.2 Situations to be observed 1174.4.2 <strong>Zakat</strong> on cash and near cash assets 1194.4.2.1 <strong>Zakat</strong> on gold and silver 1194.4.2.2 <strong>Zakat</strong> on paper money 1204.4.2.3 <strong>Zakat</strong> on stocks and securities 1224.4.3 <strong>Zakat</strong> pool of cash and near cash items 1234.4.4 <strong>Zakat</strong> on agricultural produce 1254.4.4.1 Types of agricultural producesubject to <strong>Zakat</strong> 1264.4.4.2 Starting point of <strong>Zakat</strong> duty 1284.4.4.3 Amount of <strong>Zakat</strong> on agricultural produce 1294.4.5 <strong>Zakat</strong> on income from labourand professions 1294.4.5.1 <strong>Zakat</strong> on personal income 1294.4.5.2 <strong>Zakat</strong> on minerals 1314.4.5.3 <strong>Zakat</strong> on catches from the sea 1324.5 Authorities responsible for thecollection of <strong>Zakat</strong> 1334.5.1 Department of <strong>Zakat</strong> and Income 1344.5.2 Department of General Income 1364.5.3 Authority responsible for thedistribution of <strong>Zakat</strong> 1364.6 <strong>Zakat</strong> on assets of trade 1374.6.1 Classification of commercial assets 1404.6.2 Current assets 1414.6.2.1 Cash and debtors 1414.6.2.2 Stock 1424.6.3 Liabilities arising from current assets 1444.6.4 Calculating the <strong>Zakat</strong> base 145-4.6.4.1Direct method 1454.6.4.2 Indirect method 1464.7 Summary 149u knowmy home phoneChapterfiveResearchmethodology5.0 Introduction 1535.1 Study objectives 1545.2 Research questions 1555.2.1 <strong>Zakat</strong> payment 1555.2.2 Compulsory nature of <strong>Zakat</strong> 1565.2.3 <strong>Zakat</strong> accounting 158VIII

5.2.4 <strong>Zakat</strong> auditing 1605.2.5 <strong>Zakat</strong> regulation 1615.2.6 <strong>Zakat</strong> measurement and disclosure 1625.2.7 Possibility of <strong>Zakat</strong> harmonisation 1635.2.8 <strong>Zakat</strong> collection and distribution 1655.2.9 Variations in accounting measurement 1675.2.9.1 Depreciation of fixed assets 1675.2.9.2 Allowances and reserves 1695.2.9.3 Expenditure 1705.2.9.4 Expenditure relating to previous years 1705.2.9.5 Wages, salaries and similar items 1715.2.9.6 End of service awards 1715.2.8.7 Bad debts 1725.2.9.8 Fees of firm's board of directors 1735.2.10 Percentage of <strong>Zakat</strong> 1755.2.11 Shariah supervisory committee 1765.2.12 <strong>Zakat</strong> location in the annual report 1775.2.13 <strong>Zakat</strong> method 1775.2.14 Benefit of <strong>Zakat</strong> implementation 1795.3 Research methodology 1835.3.1 Questionnaire method 1835.3.2 Design of the questionnaire 1875.3.3 Pilot study 1895.3.4 Sample and questionnaire distribution 1905.3.5 Questionnaire response rate 1945.4 Statistical analysis 1965.4.1 Descriptive statistics 1965.4.2 Statistical tests 1985.5 Summary 200ChaptersixStatistical analysis of the survey study6.0 Introduction 2016.1 Personal characteristics of respondents 2016.1.1 Investments and their values 2066.2 Major results 2086.2.1 <strong>Zakat</strong> payment on investment returns? 2086.2.2 Factors obstructing the payingof <strong>Zakat</strong> to the government 2086.2.3 Collection of <strong>Zakat</strong> 2146.2.4 Who should distribute <strong>Zakat</strong>? 219ix

6.2.5 The percentage of <strong>Zakat</strong> thatshould be paid 2226.2.6 Satisfaction with methods usedto calculate <strong>Zakat</strong> 2266.3 Accounting for <strong>Zakat</strong> 2296.3.1 The placement of <strong>Zakat</strong> in annual reports 2296.3.2 Auditing of <strong>Zakat</strong> 2336.3.3 <strong>Zakat</strong> regulation 2366.3.4 Variations in <strong>Zakat</strong> evaluation 2386.4 Proposed recommendations 2416.4.1 Reasons behind the low levelof <strong>Zakat</strong> collection 2416.4.2 Appointment of Sharia supervisorycommittee 2446.4.3 Potential benefits from <strong>Zakat</strong>Implementation 2486.4.4 Possibility for and importance of <strong>Zakat</strong>harmonisation 2526.5 Summary 256ChaptersevenSummaries, conclusion and recommendations7.0 Introduction 2587.1 Summary of the thesis 2587.1.1 Chapter one 2587.1.2 Chapter two 2597.1.3 Chapter three 2597.1.4 Chapter four 2617.1.5 Chapter five 2627.1.6 Chapter six 2627.2 Main conclusions from the study 2667.3 Recommendation for future research 2737.3.1 Reconciling accountancy measurementand <strong>Zakat</strong> base 2747.3.1.1 Working capital at the beginningof the period 2757.3.1.2 Net profit achieved during the period 2777.3.2 Recommended treatments for someExpenditure 2797.3.2.1 Depreciation of fixed assets 2807.3.2.2 Allowances 2817.3.2.3 Previous year's expenditure 281X

7.3.3 Academic fee expenditure paidto employees 2827.3.4 Amount of <strong>Zakat</strong> collected by institution 2827.4 Further recommendations 283BibliographyxviAppendix" Arabic/English versions of questionnaire and covering letter;" supervisor's introductory and explanatory letter; and," <strong>Zakat</strong> Regulations (Department of <strong>Zakat</strong> and Income).xi

List of tablesPageTable 2.1 Economic indicators of the GCC countries 36Table 2.2 Change of percentage in economic indicators of the GCC countries 37Table 5.1 Questionnaire response rate 194Table 6.1(a) background characteristics of the respondents 203Table 6.1(b) Occupation and experience of the respondents 205Table 6.2 Respondents' investments and their values 206Table 6.3 <strong>Zakat</strong> payment and its enforcement 208Table 6.4(a) Reasons behind not paying <strong>Zakat</strong> 210Table 6.4(b) Reasons behind not paying <strong>Zakat</strong> 212Table 6.5(a) Who should collect <strong>Zakat</strong> 215Table 6.5(b) Who should collect <strong>Zakat</strong> 217Table 6.6(a) Who should distribute <strong>Zakat</strong>? 220Table 6.6(b) Who should distribute <strong>Zakat</strong>? 221Table 6.7(a) Percentage of <strong>Zakat</strong> that should be paid 223Table 6.7(b) Percentage of <strong>Zakat</strong> that should be paid 225Table 6.8(a) Degree of satisfaction with methods used to calculate <strong>Zakat</strong> 227Table 6.8(b) Degree of satisfaction with methods used to calculate <strong>Zakat</strong> 228Table 6.9(a) Placement of <strong>Zakat</strong> in the annual report 230Table 6.9(b) Placement of <strong>Zakat</strong> in the annual report 232Table 6.10(a) Auditing of <strong>Zakat</strong> 234X11

Table 6.10(b) Auditing of <strong>Zakat</strong> 236Table 6.11(a) <strong>Zakat</strong> regulation 237Table 6.11(b) <strong>Zakat</strong> regulation 238Table 6.12(a) Variations in <strong>Zakat</strong> evaluation 239Table 6.12(b) Variations in <strong>Zakat</strong> evaluation 240Table 6.13(a) Reasons behind low level of <strong>Zakat</strong> collection 243Table 6.13(b) Reasons behind low level of <strong>Zakat</strong> collection 244Table 6.14(a) Appoint and pay for Sharia supervisory committee 246Table 6.14(b) Appoint and pay for Sharia supervisory committee 248Table 6.15(a) The potential benefits from <strong>Zakat</strong> implementation 249Table 6.15(b) The potential benefits from <strong>Zakat</strong> implementation 251Table 6.16(a)<strong>Zakat</strong> measurement and disclosure 253Table 6.16(b) <strong>Zakat</strong> measurement and disclosure 254Table 7.1 A sample of the recommended method 279Xlll

GLOSSARY OF TERMSFai property acquired in war without fighting.Fidth part of fai whose mode of distribution insociety is similar to <strong>Zakat</strong>.Figh Muslim jurisprudence: it covers all aspects oflife; religious, political, social or economic.Fogaha jurists who give opinion various issues in thelight of the Qu'ran and the Sunnah who have,thereby, led to the development of figh.Ghanimah war booty.Hadith a report on the sayings, deeds or tacit approvalof the Prophet Mohmmad (peace be upon him).Halal anything permitted by the Shariah.Haram anything prohibited by the Shariah.Ijma consensus of the jurists on any issue of fiqhafter the death of the Prophet Mohammad (peacebe upon him).Jahiliah the period in Arabia before the advent of ProphetMohammad (peace be upon him).Khalifah a religious head of a Moslem state.Muamalat affairs of the world.Mudarib the partner who provides entrepreneurship andmanagement in a mudarabah agreement as distinctfrom the one who provides the finance.Nisab a minimum exemption level for the levy of <strong>Zakat</strong>.Qadi a man whose knowledge of Shariah law enables himto arrive at judgements.Qiyas argument by analogy in legal and theologicalareas.xiv

Qodat plural of Qadi.Shariah refers to the divine guidance as given by theQu'ran and the Sunnah and embodies all aspects ofthe Islamic faith, including beliefs andpractices.Shura consultations, discussions or hearing differencesofopinionbefore any decision is made.Sunnah after the Qu'ran the Sunnah is the mostimportant source of the Islamic faith and refersessentially to the Prophet Mohammad's(peace be upon him) example as indicated by hispractise of faith. The only way to know theSunnah is through the collection of al-hadith.Surah a chapter in the Qu'ran.Tawheed Islamic faith in God (i. e., Allah).Ummah refers to the whole Moslem community,irrespective of colour, race, language ornationality, which carry no weight in Islam.Ushr ten per cent (in some cases five per cent ) ofagricultural produce payable by a Moslem as apartof his religious obligation, like <strong>Zakat</strong>, mainlyfor the benefit of the poor and the needy.Immam religious scholar.<strong>Zakat</strong> religious obligation on Moslems to pay apredetermined percentage of the value of theirannual savings, commodities, or properties to theIslamicstate.xiv

ChapteroneIntroduction

ChapteroneIntroduction1.0 IntroductionIslam is more than a religion because it provides acomplete code that applies to all fields of humanexistence. The Qur'an came with the message of Islam,covering everything and organising all aspects of religionand life for the individual and society.Islam is a comprehensive way of life, both religious andsecular: it is a set of religious beliefs and a way ofworship; it is a vast and integrated system of laws; it isa culture and civilisation; it is a code for social andfamily conduct; and, finally, it governs economic andcommercialnorms.One aspect of the impact of adopting the Islamic economicsystem is the achievement of socio-economic justice and theequitable distribution of wealth. The emphasis on moralvalues and, commitment to the human brotherhood providesdistributive justice to all the people in the country.According to Islamic law (Shariah), the goal of justice isachieved as a logical result of the adoption of a free-of-I

interest investment model, where the prohibition ofinterest is vital for ridding the money economy ofinjustice and exploitation as well as making it rational.The Islamic economic system contains some in-builtcorrective measures. This can lead to the elimination ofinequalities in income distribution at the narrow margins.These are in the form of the <strong>Zakat</strong>, Sadagat and other suchpayments. While other payments that Muslims are asked todo are done voluntarily, it must be emphasised that <strong>Zakat</strong>is a monetary religious duty on Muslims who are wealthy andare obliged, to pay it according to specific rules. Islambelieves in striking at the root of inequality rather thanmerely alleviating some of the symptoms.Muslim scholars have done their best to discovercircumstantial rules that cover all aspects of <strong>Zakat</strong>. Theaim has been to secure the obtainment and distribution ofthe right amount of <strong>Zakat</strong> on different properties. Yetthere have been some areas which need answers regardingpractical issues such as organising, regulating, collectingand distributing the Zäkat, that have emerged in thecontemporary economic environment.2

One important issue, which needs to be investigated, andwhich is the core of this study, is <strong>Zakat</strong> accounting. Theaim is to establish a framework towards developing basicaccounting principals for <strong>Zakat</strong> applicable to the financialsystem of Muslim countries. Moreover, dealing with thissubject would impose the necessity to investigate otherassociated issues; religious, economic and managerial. Therecent, so-called Islamic revival dominates almost allIslamic countries. The movement motivates Muslims torediscover their independent identity and religious values.In addition, there has been a changing global commercialenvironment, and real economic challenges have followed thefall of some significant Islamic economies. These changes,together with the decline in oil revenue in Muslim Arabcountries, have stimulated governments to reconsider thestructure of their economies and attempt to reshape them,making them flexible toward these developments.Accordingly, these countries have recently been involved indrawing up plans to combat the new challenges. One aspectof these new policies is the attempt to unify and harmonisethe accounting system applicable to the GCC countries. Thepossibility of applying the <strong>Zakat</strong> system in these countrieswas examined. In doing so, the Saudi experience in3

egulating <strong>Zakat</strong> has been employed as the base from whichtodevelop.1.1 Objectives of the studyThe main purpose of the study is to develop a framework fora <strong>Zakat</strong> accounting system in the GCC countries. Theintention is also to find answers to the followingquestions." What is the most relevant method of <strong>Zakat</strong> accounting withrespect to both Islamic teaching and the situation offinancial organisations operating in the Gulf?" To what extent could such a method be used throughoutfinancialinstitutions?" Which organisation should collect and distribute <strong>Zakat</strong>?" Why do some companies try to avoid paying <strong>Zakat</strong>?" What benefit would governments and economies obtain fromimplementing the <strong>Zakat</strong> system?" Who should audit <strong>Zakat</strong> accounting?" To what extent should the harmonisation process, betweenthe GCC countries, take place, and what are thepossibilities available of achieving that process?4

" Is the Saudi Arabian experience suitable and its methodsadequate as a basis from which to generalise arrangementsto the other Gulf States?For the purposes of this study only one kind of <strong>Zakat</strong> (thatimposed on trade) will be dealt with.1.2 MethodologyThe methodology adopted for the study consists of a currentliterature review and a questionnaire based on itsfindings. Information for the review has been collectedfrom various sources. The literature available on <strong>Zakat</strong>has, mainly, covered religious matters rather than economicand accounting topics. As a result, the researcher has beenobliged to develop many new ideas, serving the field ofstudy, to cover the partial lack of accounting sources.A self-administered questionnaire was used during thestudy. The qualitative (interview) technique is bestsuited for collecting data when the investigator is dealingwith a survey confined to a local area. In this study,however, the research subject deals with a widegeographical area (four neighbouring countries) It wasnot possible to travel and administer the interviews in5

four countries due to the limitation in time and resources.Thus, although the interview method has its own advantages,it was not used for the reasons mentioned earlier. Thequantitative (questionnaire) method of data collectiondoes, however, ensure a high response rate. The researcheralso has the chance to introduce the research topic andmotivate individuals to participate in the survey. Theself-administered questionnaire is less expensive and lesstime-consuming than interviewing and requires fewer skillsto administer than does the conducting of interviews(Sekaran, 1992: 201). The structure of the tests used, amongother things, were statistical moments or descriptive, andthe non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test.1.3 Limitations of the studyThe lack ofliteratureon <strong>Zakat</strong> accounting is the mainlimitation experienced by the researcher. The research has,therefore, been heavily dependent upon the writings ofwidely-known religious scholars in the Islamic world. Evenso, this study is important in terms of it being the firstof its kind to be undertaken so far in the GCC countries.There are, however, certain problems and limitations inthis study that are worth mentioning.6

The study is based on a questionnaire survey and,therefore, the results reflect only the views, experienceand opinions of the respondents as restricted by the choiceof questions used and respondents selected.The bureaucratic systems operating in the GCC countriescreated additional problems as it would take a long time toarrange to visit the departments to be studied in thefieldwork. This study includes only four countries(Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates).Qatar and Oman were excluded from this study due to thefactors of cost and time. Future research could expand thesubject groups to include those that prepare annualreports, investments analysts, religious people and bankersand ordinary members of the public. This would provide amore complete look at the issue of <strong>Zakat</strong> accounting betweentheGCC countries.1.4 Organisation of the thesisThe thesis is structured into eight chapters. Following theintroductory chapter, the second chapter highlights thebackground to the GCC countries; Bahrain, Kuwait, SaudiArabia and the United Arab Emirates, focusing on the Gulf7

Co-operation Council, location, climate, borders,population, socio-political and economic backgrounds.Chapter three reviews the main Islamic principles andhighlights the economic system as prescribed by Islam. Thisis important in order to underline the grounds upon which<strong>Zakat</strong> accounting is based. This chapter introduces the mainfeatures of the Islamic economic system. Islamic teachingscover spiritual, social, economic and political aspects ofsociety. Inevitably, Islamic economics is based on a setof value systems established by the primary sources ofjurisprudence in Islam. The chapter also reviews somedefinitions in Islamic economics and the Islamic economicsystem. In addition, it discusses the main goals of Islamiceconomics, including some of its main foundations:wellbeing; social and economic justice; and, the equitabledistribution of income. It provides a brief description ofthe main sources of economic thought in Islam. These aresimilar to the sources of jurisprudence since they are bothparts of the Shariah's objectives. The principles of unityand brotherhood are briefly outlined, together with theprohibition of riba in Islam, the associated moral valuesand their relationship with economic realities. It is shownthat the prohibition of riba is the main difference8

distinguishing Islamic economics from conventionaleconomics. Islamic views on economic problems are alsopresented. Finally, a detailed account of the role of thestate and its intervention in the economy in an Islamiccontext is briefly reviewed.Chapter four deals with accounting for <strong>Zakat</strong>, which is amonetary religious duty on wealthy Muslims. The researchmainly examines various ways that Muslim scholars havesuggested how <strong>Zakat</strong> should be calculated. <strong>Zakat</strong> should bedetermined in different situations and a method chosen thatis the most appropriate.Chapter five provides a detailed analysis of the researchquestions and outlines the adopted methodology. Inaddition, a discussion of the advantages and disadvantagesof using a questionnaire are presented together with pilottesting of the questionnaire, sampling procedures andquestionnaire distribution. The statistical tests employedin this study are also discussed.Chapter six presents the findings from the responsesreceived from those responsible for <strong>Zakat</strong> accounting. Basedon the findings of this study, recommendations are made.9

Chapter seven summarises thefindings of the study andhighlights its main conclusions.10

ChaptertwoGeneralbackgroundtotheGCC states

ChaptertwoGeneral background to the GCC states2.0 IntroductionThe Arabian Gulf is an area which most people associatesolely with the production of oil. This is a gross over-simplification as it ignores its people, its land and itshistory. Although the wealth generated from oil exports hasaffected many aspects of economic life throughout the Gulfregion, it must be remembered, however, that the social lifeis still deeply traditional and remains unchanged. Inaddition to the common historical and socio-culturalbackground, the Gulf countries have similar problems andaspirations. The most important of these are regionalpolitical stability and economic and social development.These two factors appear to be the main reasons behind theestablishment of the Gulf Co-operation Council.This chapter, therefore, reviews the main characteristics ofthe Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) countries. For eachcountry, a general description is given, followed by briefeconomic details as well as their respective social andcultural backgrounds. An analysis of important economic11

indicators is given and, in the light of this analysis, theimportance of <strong>Zakat</strong> to the economics of the GCC countries isexplained.2.1 The Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC)Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UnitedArab Emirates formed the Gulf Co-operation Council in 1981as a unified defence, political and economic organisation.The headquarters of the GCC is situated in Riyadh, SaudiArabia. The GCC's <strong>Unified</strong> Economic Agreement was signed in1983, with the establishment of a single common market asone of its objectives. Several significant GCC-wideregulations have been implemented since then, including theremoval of tariff barriers between member states, subject toa 40% local value-added tax rule, with certain exceptions(Rumaihi, 1986).All GCC member countries have the same rights towards theownership of property as well as towards most businesses inany GCC country. GCC-owned companies have equal access toincentives and facilities, and are accorded the samepreferential treatment in government purchases as locallyowned companies. Many regulations and policies have been, orare being, harmonised in all GCC states (Olfet, 1988).12

in the following section, various features of each of theGCC countries are considered. Only a brief discussion willbe given on Qatar and Oman, as these two countries are notcovered by the present study.2.1.1 BahrainWith a total area of 692 square kilometres, Bahrain consistsof an archipelago of more than 30 islands in the ArabianGulf, 22 kilometres from the eastern coast of Saudi Arabiaand 28 kilometres from the western coast of Qatar (Ministryof Information, 1998)The largest of the six principal islands is also calledBahrain which, translated loosely from the Arabic, means twoseas. It has a total land area of 586 square kilometres andpopulation of 620,000. The oil town of Awali is located inthe centre of the island. Manama, the capital and commercialcentre, is located in the north-east corner of the mainisland and contains more than a quarter of the population.Bahrain is a member of the United Nations, the Arab League,the International Monetary Fund, and the International Bankfor Reconstruction and Development (Bakri, Jali, Ibrahim andGadomi, 1998).13

2.1.1.1 Economic backgroundRelatively small oil reserves and a fast-growing populationprompted Bahrain to pursue an economic diversification andliberalisation programme in the 1970s. As a result, it hasachieved a more balanced economic structure (with strongindustrial and financial services sectors) than other oil-producing countries in the Middle East (Economic Affairs.1998).Earnings from oil were scheduled to rise by 20 percent in1993. This was due to an arrangement with Saudi Arabia toincrease Bahrain's share of the output from the Abu Saf aoilfield, which is in Saudi territorial waters. Oil revenuesrose by 20 percent in 1993 and 12 percent in 1996. In 1997,Bahrain's GDP decreased by 1.2 percent and Per capitaincome was US$8,420 (Economist Intelligence Unit Statistics,1997) .Inflation has been almost non-existent in Bahrain in recentyears, as a result of the government's generallyconservative monetary policy, its generous subsidies forbasic commodities, as well as a slackening of demand in theeconomy(Information Published by Government, 1996).Bahrain was the first country in the southern Gulf region to14

have an oil-based economy. Its oil reserves are small,compared to Gulf standards, and, at the present rate ofextraction, are expected to last only until the end of thedecade. Renewed exploration and government concessions sincethe early 1980s have yielded no new commercially viablesources so far (Rumaihi, 1986).The crude oil and natural gas sector's contribution to GDPhas declined in the last decade, from 17 percent in 1993 to16 percent in 1996, as a result of diversification anddepressed world oil prices. Crude output in 1996 was about40000 b/d(Statistics Published by Ministry of finance, 1996).Bahrain exports the bulk of its oil not as crude but asprocessed petroleum products including jet fuel, gas oil,fuel oil, gasoline, naphtha and kerosene. Together, theseaccount for about 85 percent of the country's totalpetroleum exports. Apart from processing locally producedcrude oil, Bahrain also processes light crude from SaudiArabia (Statistics Published by Ministry of Petroleum, 1996).Bahrain is the base for several heavy industries that arepan-Arab ventures in which the Bahraini Government holds themajority stake. The first to be established, in 1971, wasAluminium Bahrain (Alba). Another example is the Arab15

Shipbuilding and Repair Yard (Asry) which deals with bothlarge tankers and smaller ships (Statistics Published byMinistry of commerce, 1996).The government has given priority to developing theagriculture sector in order to reduce the country'sdependence on imported foodstuffs. Less than 6 percent ofBahrain's total area is considered arable land, however, andmost of this is confined to a narrow strip in the north ofthe main island. The scarcity of water, a hostile climateand the expanding housing and industrial developments arealso constraints to agricultural development (Bakri, et al,1998).The contribution of agriculture to Bahrain's GDP is minimal,amounting to just 2 percent in 1996. In 1997 theagricultural sector satisfied around 15 percent of thedomestic demand (EIU Statistics, 1997).Bahrain owes its success as a primary financial centre inthe Gulf to its key location within the region between Asiaand Europe, its excellent communications system, and itsliberal regulatory environment. Established in 1973, theBahrain Monetary Agency (BMA) functions as the central bank;it is responsible for issuing currency and supervising16

anking and investment institutions in the country. As ofJanuary 1994, Bahrain had 18 commercial banks, twospecialised banks, 51 offshore banking units (OBUS), 22investment banks and 47 representative offices of foreignbanks. The financial institutions sector also includes 21insurance companies and 42 exempt insurance companiestrading offshore. An important event in Bahrain's financialdevelopment was the long-awaited opening of the Bahrainsecurities Exchange in June 1989(Information Published byMinistry of finance, 1997).Bahrain is dependent on imports for the majority of itsneeds, whether for consumer goods, capital goods or rawmaterials. Although Bahrain is an oil-producing country, itsoutput is insufficient to feed the giant Sitra oil refinery,and crude supplies (largely from Saudi Arabia) are thecountry's primary import, accounting for nearly 40%, invalue terms, of total imports. Machinery and transportequipment comprise the largest non-oil import category andrecorded the most rapid growth over the past few years. TheUSA, the UK, Japan and Germany are the four leadingsuppliers of non-oil imports (Information Published byMinistry of Commerce, 1997).17

2.1.1.2 Social, Cultural and political backgroundBahrain is the second smallest country in the GCC and hasthe smallest economy. Although the population is Arab andMuslim, more than half the population is from the Shiitesect. The rulers, however, are Sunnites. Because of thesmall size of the Island, Bahrain society is predominantlynon-tribal as opposed to most other societies in the Gulf.The head of state comes from the ruling family and has aveto over the partly elected parliament.Despite being the poorest GCC country, Bahrain comparesfavourably with other GCC countries when it comes to itshuman development. In 1994, life expectancy was the thirdhighest (72.0 years), infant mortality was third lowest(20%)in the GCC. Bahrain also has the highest adult literacyrate (84%), the highest school enrolment (95%) and thelowest population growth rate (3.7%) (United NationsDevelopment Programme (1997). Overall, Bahrain has thehighest human index value of 0.87 in the GCC (Radwan (1998).Bahrain also relies on a large number of expatriates whorepresent 39% of its population. (Gulf News, 1997). Becauseof the liberal nature of Bahrain society, women's activityrate is the second highest in the GCC, with womenrepresenting 20% of the total workforce (Kapiszewki, 1998).18

2.1.2 KuwaitKuwait is situated at the north-west tip of the ArabianGulf, between Iraq in the north and west, and Saudi Arabiain the south-west. In total the state is 17,818 squarekilometres (7000 square miles) which include several islandsscattered in the Gulf. (Ministry of Information, 1998).The emergence of Kuwait as an oil-rich country hasundoubtedly transformed the nation from a state of poverty,to one of the highest per capita income regions within arelatively short time (per capita income was US$13,867 in1997). This was helped by the fact that Kuwait has a verysmall population, which, according to the census of 1997,had reached 1.81 million (EIU Statistics, 1997).Before the discovery of oil, there was no need for foreignlabour. Following the discovery of oil, the country hasgrown dependent upon expatriate workers for the running ofoil companies. Moreover, the acceleration of economicdevelopments to absorb part of the oil wealth necessitated agrowing demand for expatriates with various skills andtalents in virtually all fields of economic activities aswell as the civil service. This was accentuated by ashortage of national manpower, a high illiteracy rate and arefusal by Kuwaitis to take manual jobs (Rumaihi, 1986).19

2.1.2.1 Economic backgroundThe Kuwaiti oil industry has contributed on average 95percent of GDP to the revenue of Kuwait; 98 percent of thiscomes directly from export of oil and gas. Nevertheless, oilrevenue has decreased by 11 percent in 1997 compared with 6percent in 1994 (EIU Statistics, 1997).Government expenditure also decreased by 6.3 percent in 1996compared with 5 percent in 1994. Climatic conditions and theabsence of flowing water also eliminate the chances forexpanding agricultural production. As a result, the economyis dependent on foreign trade. The ratio of exports to GDPwas more than 90 percent in 1995. This ratio has, however,been volatile, declining in recent years due to thereduction of oil exports (IMF Statistics, 1997).The low domestic aggregate demand due to the small size ofthe domestic market hinders industrial expansion andeliminates the benefits of mass production. Kuwait alsodepends on the rest of the world in many respects,especially in relation to the marketing of oil, which makesit vulnerable to international market forces. Also, thechannelling of surplus funds abroad, due to limited localinvestment opportunities, subjects the economy to externaleconomic pressures and policies (Rumaihi, 1986).20

2.1.2.2 Social, Cultural and political backgroundKuwait is the smallest country in the GCC but is the thirdrichest economy in the Gulf. A large proportion of thepopulation is Shiite, but the ruling family is Sunnite. LikeBahrain, Kuwait is largely liberal. Politically, althoughthe head of state (the Emir) is unelected, the country hasan elected parliament. However, the ruler has the ultimatesay in political affairs.Kuwait, like most GCC countries, is predominantly a tribalsociety. Despite the devastation of Kuwait during and afterthe Gulf War, Kuwait is doing well in terms of its humandevelopment. In 1994, Kuwait had the highest life expectancyin the GCC with 75.2 years, the lowest infant mortality(20%), and the third lowest population growth rate (5.6%).Kuwait also has a very high adult literacy rate (79%)(UNDP,1997). Overall, Kuwait has the second highest human indexvalue of 0.84 in the GCC (Radwan, 1998).Kuwait relies heavily on expatriates. Between 1995 and 1997expatriates represented 84% of the workforce, the secondhighest proportion after the UAE. The women's activity ratein Kuwait is the highest in the GCC, with women representing33% of the total workforce (Kapiszewki, 1998). This suggests21

that Kuwait's society is relatively more liberal than otherGCC countries. Despite its liberalism, however, Kuwait ismostly a tribal society. Tribal links are very important insocialrelations.2.1.3 Saudi Arabia (SA)Saudi Arabia is divided into five main regions. The EasternRegion contains 13 percent of the population and is locatedin the coastal area along the Arabian Gulf, where thecountry's main oil reserves are located. The Central Region(Najd), contains about 25 percent of the total population.Its capital is Riyadh, which is also the capital of theKingdom. The Western Region (Hijaz), accounts forapproximately 34 percent of the population, most of whomlive in the holy cities of Makkah and Medinah, in Jeddah,and in the mountain resort of Taif. The South-west Region(Asir), is inhabited by about 16 percent of the population,almost all live in villages in the mountains and along thecoastal plains. Its main city is Abha. The Northern Regionaccounts for about 12 percent of the population, with arelatively large proportion living in rural areas or in thecities of Tabuk, Hail, Sakakah and Arar. The Rub al Khaliis a wide expanse of barren and unpopulated land to thesouth-east (Ministry of Information, 1998).22

Saudi Arabia is a monarchy, with strong historical linksbetween the government and the Islamic religion. The powersand duties of the King are defined according to the Shariah(Islamic law). The King serves for the good of the people ofSaudi Arabia. Indeed, although supreme authority rests withGod, the enforcement of Shariah law is the responsibility ofthe ruler. The constitution consists only of the Holy Qur'anand the Shariah (Rumaihi, 1986).The Kingdom is divided into 14 governorates, or emirates.The Al-Ahssa emirate is contiguous to the Eastern Region;the emirates of Riyadh and Qassim are in the Central Region;Makkah and Medinah are in the Western Region; Tabuk,Qurayyat, Al Jawf, Hail and the Northern Frontiers are inthe Northern Region; and Asir, Najran, Jizan and Baha are inthe South-West Region. Each emirate is divided into sub-emirates, and urban and rural districts. Municipal districtsand tribal village agencies administer local services (Al-Hogael, 1997).The population census of October 1992, the first censussince 1974, estimated Saudi Arabia's total population atalmost 19.48 million in 1997(IMF Statistics, 1997).23

2.1.3.1 Economic backgroundPossessing the world's largest oil reserves, Saudi Arabiacontributes approximately 10 percent of the world's totaloil production. Saudi Arabia has supported its economicdevelopment with its earnings from oil. Although the oilsector continues to be a dominant factor in economic growth,its contribution to GDP has been steadily declining due tothe volatile world oil market and the recent expansion ofthe non-oil sector. In 1997, GDP in SA had increased by 2percent whilst the per capita income rose to US$7,291(EIUStatistics, 1997).At present, oil prices are currently low and it is estimatedthat persistently weak oil prices will lead to a fall ofmore than 20 percent in oil revenue. Subsequently, thisforces the government to reduce expenditure in order tostabilise debt. Government spending in 1997 was US$59billion, or equivalent to 40% of GDP. This is US$1.9 billionless than in 1996, when actual spending exceeded plannedspending by US$10.40 billion. Furthermore, governmentrevenue budgeted at US$40.26 billion, rose to US$44 billiondue to positive changes in the oil market. Governmentrevenue in 1993 rose marginally, to US$45.01 billion,despite the fall in oil prices (EIU Statistics, l997).24

In addition, Saudi Arabia is also privileged to have vastGas supplies. Associated gas from the Kingdom's oilfields ischannelled into the US$12 billion Master Gas-Gathering<strong>System</strong> (MGS), which is one of the largest engineeringprojects in the world. The MGS comprises gas-gatheringtreatment and transmission plants, and provides the basisfor the development of the Kingdom's petrochemicalindustries.The two major mineral sectors deal with the extraction ofbuilding materials and metals for further processing andindustrial use. By 1993, these two sectors contributed 2percent of non-oil output (Information Published byGovernment, 1996).The government's 1974 industrial strategy was intended toachieve development and diversification of the non-oil basedindustrial sector, alongside substantial private sectorparticipation. Much of the value of these industrialdevelopments has been in the refining and petrochemicalindustries, which accounted for 60 percent of the totalvalue of industrial investment between 1985 and 1992.However, in 1996 the total number of licensed industrialprojects in the SA was still 2,078, with a total investmentof over US$33.33 billion (Ministry of Finance, 1996).25

Accordingly, the SA Monetary Agency (SAMA), as with mostcentral banks, is acting as the monetary agent of thisgovernment. It is responsible for the exchange rate, as wellas monetary control and the control of financialinstitutions in the Kingdom. Indeed, SAMA is seen to be in astrong position to exercise control over inflation. This isbecause money supply growth is determined principally by thelevel of government spending, by private sector creditexpansion, and by the balance of payments deficit or surplus(Ministry of Finance, 1996).At present, the commercial banking sector consists of 12banks, with 1,170 branches throughout the Kingdom and atotal working capital of US$8,051.5 billion; compared withUS$11,374.6 billion in 1996(IMF Statistics, 1997).2.1.3.2 Social, Cultural and political backgroundSaudi Arabia has the largest economy with the largestpopulation in the GCC. Unlike Bahrain and Kuwait, the vastmajority of the population is Sunnite which makes it a morehomogenous population. Another important difference is theextreme conservatism of Saudi society as opposed to theopenness of the Kuwaiti and Bahraini systems. The role ofreligion and tradition in Saudi Arabia is extremely26

important to the everyday life of Saudis. The Shari'ah isstrictly observed by the population and is firmlyimplemented by the government. Religious scholars are highlyregarded and respected. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia is amonarchy, although a consultative council was establishedduring the early 1990s. In addition to conservatism,tribalism is an obvious feature of the Saudi Society. Triballinks and relations are imperative to Saudi people in everyaspect of their life and work.Despite being the largest oil producing country in the GCC,Saudi Arabia does not compare favourably with other GCCcountries in terms of its human development record. Amongthe four countries included in this study, Saudi Arabia hasthe lowest life expectancy (70.3 years), the highest infantmortality rate (27%), the lowest adult literacy (62%) andthe lowest school enrolment ratio (56%) (figures for 1994)(UNDP, 1997). It is not surprising, therefore, to see thatSaudi Arabia has the lowest human development index value(0.77) among the four countries (Radwan, 1998).Because of its large population, Saudi Arabia needsproportionately less expatriate workers than the othercountries. Indeed, in 1997 expatriates represented only30.8% of the total population, which gives Saudi Arabia the27

lowest rate among the four countries included in thisparticular study. However, because of its extremeconservatism, women represent a mere 9% (of whom 20% areexpatriates) of the total workforce (Kapiszewki, 1998).2.1.4 The United Arab Emirates (UAE)The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of sevenemirates: Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al-Quwain,Ras Al-Khaimah and Fujairah. The total area of the UAE,excluding islands, is about 77,700 square kilometres. AbuDhabi and Dubai are the two largest emirates (Ministry ofInformation, 1998).2.1.4.1 Economic backgroundThe provisional constitution of the UAE (1971) establishedvarious posts and offices. These include the President, theVice President, the Supreme Council, the Federal Council ofMinisters, the Federal National Council, and the Judiciary.The Supreme Council, comprising the hereditary rulers of theseven emirates, is the highest federal authority (Rumaihi,1986).Abu Dhabi's oil wealth has made it the most influential ofthe Emirates. Its ruler is the president of the federation,28

and the city of Abu Dhabi is the centre of federalgovernment activities. Since its establishment as afederation in 1971, the UAE has been a member of the UnitedNations and the Arab League. It is also a member of theInternational Monetary Fund, the Organisation of PetroleumExporting Countries (OPEC) and the Gulf Co-operation Council(GCC) (Bakri, et al, 1998).Official estimates placed the population of the UAE, in1996, at 2.44 million, which is significantly higher thanthe 2.08 million recorded by the 1993 census(StatisticsPublished by Government, 1996).The UAE Government's efforts, since the early 1980s, todiversify the federation's economy and reduce its dependenceon oil, have boosted the manufacturing and service sectors,particularly in Dubai's Jebel Ali Free Zone. They have alsoresulted in a steady decline in the contribution made by theoil sector to the GDP, which decreased from 40 percent in1993 to 35 percent in 1996. Nonetheless, the UAE remains oneof the richest nations in the world. Its per capita GDPmeasured at US$19,095 in 1997(EIU Statistics, 1997).Sustained economic growth will depend, however, on thestrength and stability of oil prices, as well as the29

country's success at economic diversification. Although oilrevenues declined by 4 percent from 1993 to 1994, theyincreased in 1995 by 15 percent (Statistics Published byMinistry of Petroleum, 1997). The UAE has about 11 percentof the world's total oil reserves, making them the thirdlargest in the world after Saudi Arabia's and Iraq's. TheUAE have proven oil reserves of 98.1 billion barrels,equivalent to more than 100 years' supply at the currentrate of extraction (EIU Statistics, 1997).While the UAEIs industrial base has broadened considerablyduring the last decade, much of the industrial sector isstill centred on hydrocarbons. A small home market hampersthe sector's diversification, as do the limitedopportunities for exporting to neighbouring GCC states. Thisis because each has its own industrialisation policy(Statistics Published by Ministry of Commerce, 1997).Similarly, the manufacturing sector comprised 9 percent ofGDP in 1993, compared with 8.5 percent in 1996. The fastest-growing industries are textiles, metal fabrication, food andbeverages, chemicals (particularly fertilisers) and basicmetals (IMF Statistics, 1997).30

2.1.4.2 Social, Cultural and political backgroundThe UAE has the highest per capita income in the Gulf.Socially and culturally, the UAE lies somewhere betweenKuwait/Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, although it is much closerto Saudi Arabia. Like Saudi Arabia, the vast majority of thepopulation is Sunnite. It is strongly tribal, but someemirates are less conservative than Saudi Arabia. Otheremirates, including Abu Dhabi, are almost as conservative asSaudi Arabia. Consequently, although the roles of religionand tradition are important in the UAE, they have lessinfluence in Saudi Arabia.The UAE is ruled by a supreme council with one member (theEmir or Sheikh) from each of the eight emirates. Thepolitical system is based on power sharing, with thepresidency going to the Emir of Abu Dhabi and the primeminister to the Emir of Dubai. However, each Emir hasabsolute power within his own emirate.According to the latest statistics of 1994, the UAE had thehighest life expectancy (75.2 years), the lowest infantmortality (17%), the second highest adult literacy rate(79%), and the second highest school enrolment ratio (82%)(UNDP, 1997). In general, the UAE has the second highesthuman development index value (0.86) in the Gulf (Radwan,31

1998). The UAE also has the fastest growing population inthe Gulf, with a growth rate of 9.8% between 1960 and 1994(UNDP, 1997).The combination of its small population size and fasteconomic growth meant that the UAE needed proportionatelymore expatriate workers than the other GCC countries.Indeed, in 1997 expatriates represented 90.4% of the totalpopulation, which is the highest among the Gulf countries.The conservative nature of the UAE society can be seen fromthe very low percentage of women throughout its workforce(10%) (Kapiszewki, 1998).2.1.5 OmanThe Sultanate of Oman is located in the extreme south-eastcorner of the Arabian Peninsula. It has a total land area of300,000 square kilometres. Most of this is sparselypopulated desert punctuated by dry riverbeds (known locallyas wadis) with occasional green valleys (Ministry ofInformation, 1998). "Oman's population (estimated now to be 2.4 million) stood at2.26 million in 1997. Most of these belong to the strictIbadhi sect, whose principles are followed by thegovernment(Statistics Published by Government, 1997).32

The Omani economy mainly depends on its oil and miningsectors. Although oil's share of GDP declined from 6percent in 1990 to 4 percent in 1996(IMF Statistics, 1997).Although exports of crude oil are the main source ofgovernment revenue, Oman is one of the smallest oilproducers in the Gulf (MOI, 1998).Seventy percent of Omanis rely on agriculture for theirlivelihood, although mostly at a subsistence level. The lackof sufficient water resources are the greatest constraint tothe development of Oman's agricultural potential (Bakri, etal, 1998). Oman has very limited industrial activity, owingto the small domestic market and the lack of trained Omanimanpower. The sector has grown rapidly, however, and,according to the bulletin published by the Gulf Co-operationCouncil in 1997, it expanded at an average annual rate ofnearly 44 percent in real terms between 1990 and 1993. In1996, its contribution to GDP at constant prices reached 4.8percent. There were 2,334 registered companies in thecountry in 1996(IMF Statistics, 1997). The value of importsincreased by 63 percent to US$11,342.13 million in 1996. Thelargest single category of imports (39 percent of totalvalue) continued to be machinery and transport equipment, of33

which road vehicles form the most significant component (IMFStatistics, 1997).2.1.6 QatarThe Qatar Peninsula projects northwards from the much largerArabian Peninsula in the southwestern Arabian Gulf. With atotal area of 11,437 square kilometres, it extends some 160kilometres from north to south and a maximum of 80kilometres from east to west and current estimates put thepopulation at 600,000. The capital of Qatar is Doha(Ministry of Information, 1998).In the west, Dukhan is the focus of the onshore oilindustry, while Umm Bab to its south is the site of a cementplant. There are only a few other permanent settlements inthe country, all of which are located in the peninsula'snorthern half (Bakri, et al, 1998).The country achieved healthy nominal GDP growth rates of 5.1percent in 1993 and 8.5 percent in 1997. Previously,favourable oil earnings have enabled Qatar to achieve a highstandard of living. Although per capita GDP has fallenmarkedly over the' past decade, it is still comparable withthat of developed countries. In 1997, per capita GDP wasaround US$14,903(Statistics Published by Government, 1996).34

In recent years, the government has strived to develop thenon-oil sector in order to reduce the economy's reliance onoil revenue. As a result of falling oil prices, the oilsector's contribution to GDP has been decreasing gradually,from 32 percent in 1993 to 31 percent in 1996. Themanufacturing sector comprised 11 percent of GDP in 1993,1995 and 1996(EIU Statistics, 1997).Adverse geographical conditions severely limit thedevelopment of Qatar's agricultural sector, allowing acontribution of only 1 percent of GDP in 1996 (InformationPublished by Ministry of Commerce, 1996). Qatar remains asmall market for imports. Its main sources for the bulk ofits imports, which consist of industrial machinery andequipment, materials and supplies, consumer goods, and foodand beverages, are Japan, UK and the USA (IMF Statistics,1997).2.2 Aggregate analysis of the economicstructure of GCC countriesTo shed light on changes in economic conditions in the GCCcountries in the last 5 years, economic indicators for eachof these countries were compared and are reported in tables2.1 and 2.2 on the following pages.35

0,'ý-n nn n n N JO JO C\ O I/1 h0I/1r- ty M M Vi M M M4yWvh N O O O Ox 0 0 v v v I TM M14i' V RO N V1 'n 'n k/1v v v v v vVi Il: Il: rý I-:a a C O x 0 ] oN N. n n nCl! N Cl! M M M Mrl:V'-0 0 0 O O 0 0 0 0 O O O O O O M M M M M M M M M M t"'i M M (n MIbf3vM NOÖ IýM V' V NN N ÖO M M MN V OM 'V JOý/1 Vl ýO Oen _nM769 V h M N69 69 69 6969 ffi 69 69MM v? v7 VM L1 JÖf'1p n O VNVýN_Myj 69 69 69N 'V N h ýO VV eV CT V' ýO OýoV n ÖýD VlV' infA FA 69 69 69ýÖM ý: J t? týlhV^v^C1 n JO M O JO Vl MN MM JO nCTtý NnMn'v'Y-Nýfv E13 EA 5q Vi fA 6Ab9-zrvN69QZaZNC0 r-E N 9o N ýoLnE '010 '0 In N ný An'nNCON cl Ic `OMi00a i v i 00Vlp oo M M,'D V Cý 'DVt 0 0 V 7, NVO 69 V) 64 V) yj 6s yj b9 Y3 66 69 69 69ODbhiryMý: JMNMr- nMäpN'O. M MpMOOr- O N- nO00 NC'4N M 1 O00Zh U%ý% ch.Z + 0O5 . 111 V) V) E01)Gn Go) boNOZC)CCVN 7 v'1 vl V n ý`-- G1 'ýV N L1 .-. Oý M Nö n 'U lý l0EyÖEcriOý .G1 O G1 O ýj M.tai'O oo vi 'O'nD ''! 1 'n O N nýO V C% 'DÖ10 Ov1 'VDv0u V [t V 00.= M o0 Mp ^ 'n N n 00 -- ...ýýp M Os 10 O, vi 7, M p Oyd VN N N Mv) yýjO 00fA69_fA_69Gý_ O 769 6900 69121,6969Vl69y'V)M6969696969 69M64en M69M.SN00 V .MQ. QO O 'n Z Z63 690S.. r"ciCE0Ný'nn69 16O '0 O .--ý--ý 10 n rýO V^ Nhý0 0Vý fA ll! i69MO'ONen_69 ViL1MOM_VinV^Mn N N N- OOOc{ N n Nooýco Cln'ON'D cD 'O69 69 69 69 69 69ONO'eý'O'ITV.N M69_69COG1OllM_69MO ^ n ' D NM^ vlM 0 O N O 5ClOVO00nýO J n n N696969 69 69 _69NV70Vý 00'VN0O_6A 69 69hQ5OG 1_69VitW-ÖäO0.V 'V Os O N N M 10 1 V N 00 ýf n: N 1 T In = On-,- V/100 M 00 t Nh h ý/l ,sO V ' ýO G, O --ý O O -ý - N vl ý! 1 Vl 'fl ''J O N M V1O Ö Ö O C. - N Ni N N N N NÖ O O O O -- - -N N N N N- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -VNGýME--(.a 2VyInt1NOC,ME Vii 00 OV VQ V9 69 69Qr n00 U' N V s"O V O--ý --ý M n M v.ýO O M 00 OO N N Dnýn 'O '! 1 sO VlM_ N V ý. V O /1 O .-+n N1 '""ý M L1 Mr--.-.vlV1 Vl M V ýO 00n69 69 N N N N Nb9nnyj69 69 69 69 69 69 6H 69 A6690 NN ýO N ýO'6'ý00G1ooios.... h0O N vl. NN N '0nN n'M NA00 O F4 ul V1 vi C,.... y M M_d9 69 6A'D5O ýDN ý: J Ny0n ýD G1'O O '/1h- d O O VM M V V'69 b9 69 69v12rJ00 O.NMN_N 01 p N IýON 00 n¢n00 MJ OZ Z N MM OýO Vl910WO_E6 Ni 00MU 9 W 4 69 69 6ntr=Vaý`V^I. C.ý, -ý O V^ 00 M'DG1 n M'cJnNNZ.-'ý.M'n 69 69 69 69 Nc-G1V00NVw'D Z'O V' t'q,nU' 0 V O Q QN O E Cn\ONO CS Z ZVEf3 FA5 a00NHU. N+- - - - - - - - - - - - - -M C/) 0 n M h 10 n M M '/1 J n en 1 '/1 J na Ea c oý Q M Qo cý a/1 I'Dn Ma cCS VCS 1,Cýcý cý a o a s S a o a a c e ý a s L cý ý a a s c E E c, cN aE ýe °Rsm O O' vý Hcý . "O'0ýncýýzU

sv2ýJbbQr N m N n O h CC o O n h O ýO G 'DrQ N n NQ Q h ON 0 0 0O r `D' ri tý b N ý'1 n ý' N N N O O O 0 O0 O N ý'1O0ýDn^hQ Qj v Q z 7-.(f3t/).0tH11M11 IP°'A V1O O Om QY1 N . -. t ý 1Nr- N O N N N NýC` a j-cý a n n N 0 y y n Z 'DC, > .Nl OhO ýn Qt+f Vl Opn QON n O N Q O0n '° w N 00O0 1n v ý'rrO O J O O ra O ý rn ý j , .------------ ----------L7m ýD hh r Ö Qý00 ýOtýlcZ QhnýhQVl7ý/1Qlýl .+NNN Q0, ý QNnQbG-tQrrýDNa'O ý'1 ý/1 rN j 0 0 0 -U'-aNOa Yf Q ¢m ý '? Z^c'AlfNlQZ+00 VlC M QQa n m O O M M m '0 ' r1 a ýD N r O M - m mh a ý0 Q M N N Q n n.. MI N Oý aN N N .. ..t"1 N N r N M tý1 N N N -ý O O O O OQOaaro0_m m n 'ýN m4 of ý,-- -- -- ------ -- - - -brýJ: Q.NYl h O aN Ný .Q ja'ýO O -0, n Na ^OI`hQ N 1 0 Ö...Q Q N^NQ0 NNO O O O Oo0NrQfir [;. ,Zh N NmMn o0 N r..9C ýO e'1 N Q NQGG O ° a tn t+l ý° M'ýý h N N O r eýi tai V1 r t'1riÖOOtýlO 10 h -G N aO j?O "' NmaTNVlnViNvlNVieh V'1 D 10 O O O 0 0aVlr N ý+ QlOm ý QO O f '1 C N N Z 7-CaýbAeýCaývaýA.0bACel4UNNa)mQE*nT 0.ö °n Q -aDaraE a a a a ae[c>6ýQa-aOaraT- - - - - - - - -7 aCOöE o Koö,, tl w ntdO0 N aQaDntý1Q°ra- - - - - -ö a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a V a a a a m a a o: a a a a auädyGVC yvenV°pOG W ý d ` VW'OHaAuý °d° 6 pe ä D as a+0ýt L. p v'nä.ry m d v_yCO6 O CiaV n c n a°'.4 ýl aQmäCVQavýaDananRäcE°.M1aQaýnaýDanaVüOCÖDtdyöäCvn1aQavlaýOaraa. ). fl00000 .2rn yw¢IzC)Co W.

Table 2.1 reveals that Bahrain reported a decrease in oilrevenue, from US$923 million in 1993 to US$847.3 million in1995 (no figures available for 1996 or 1997). SA, Kuwait,Oman, Qatar and the UAE, on the other hand, reportedincreases in oil revenue: from US$28,266.6 million in 1993to US$42,666.6 million in 1997 for SA; from US$8,217.2million in 1993 to US$10,350 million in 1997 for Kuwait;from US$3,463.2 millions in 1993 to US$5,776.36 million in1997 for Oman; from US$2,110 million in 1993 to US$3,133million in 1996 (no figures available for 1997) for Qatar;and, from US$8,247 million in 1993 to US$9,052.8 in 1995 (nofigures available for 1996 or 1997) for the UAE. There wasa general decline in oil revenue towards all these states in1994, except for Oman where it rose from the 1993 figure ofUS$3,463.2 million to US$3,680.7 million in 1994.It is evident from table 2.1 that the GCC countries areheavily dependent on oil revenue. Table 2.2 shows the oilrevenue as a percentage of GDP. All countries, with theexception of Bahrain and Oman, reported a general increasein their oil revenue as a percentage of GDP. Bahrain's oilrevenue (as a percentage of GDP) has declined since 1994 byalmost 18 percent. Oil revenue (as a percentage of GDP) inSaudi Arabia increased by 29 percent in 1996 compared with38

11 percent in 1995. In Kuwait, the oil revenue (as apercentage of GDP) increased from 8 percent in 1993 to 24percent in 1995 and 11 percent in 1996. The UAE registeredan increase from 17 percent in 1993 to 15 percent in 1995.Oman saw a decrease in oil revenue (as a percentage of GDP)from 6 percent in 1994 to 3 percent in 1995.Table 2.1 shows that all countries, with the exception ofKuwait (showing a marginal decline), have reported increasesin their per capita income. Bahrain and Oman, althoughshowing some fluctuations, have remained with relativelyunchanged situations, although Oman (unlike Bahrain, wherethere was an increase) did record a drop in income in 1994.This was despite Oman being alone, amongst the GCC states,in not reducing its oil production in 1994. Bahrain was theonly state to record an increase in per capita income in1994. The per capita income of the UAE showed a slightfluctuation (a reduction in 1994) but since then growth hasbeen recorded, resulting in it being the highest in theregion and one of the highest in the world (US$19,095 in1997). Kuwait also recorded a drop in per capita income in1994. Although Kuwait has experienced a steady increasefrom 1994 to 1997, the highest figure in 1993 (of US$14,511)has not yet been equalled. In this respect Kuwait and the39

UAE are not alike, as the UAE has significantly exceeded its1993 figure. Kuwait is the only member of the GCC not tohave equalled or exceeded its 1993 per capita income. SaudiArabia also presents an anomaly in this group of states inthat it alone registered a drop in per capita income in1997, over its 1996 figure. However, there was stillsufficient growth up to 1997 to exceed the 1993 figure.Qatar has registered a steady and, largely, consistentincrease in per capita income from 1993 (US$12,780) to 1997,when it reached US$14,903, despite it also experiencing adrop in per capita income in 1994.There is a reduction deficit in some countries and anincrease in deficit in others. This is due to an increase innon-oil revenue and reduction of expenditure. The UAE budgetindicates a reduced deficit in 1997 by 3 percent, comparedwith 13.4 percent in 1995. Bahrain announced a deficit of 4percent in 1997 compared with 2.4 percent in 1996 and 3.1percent in 1995. In Saudi the deficit reduced from 10.6percent in 1993 to 3.3 percent in 1996 and 4.5 percent in1997. In Oman and Qatar the deficit reduced from 8.7percent and 8.9 percent in 1995 to 4 percent and 3.4 percentin 1997 respectively. Debt problem is one of the mainfactors influencing confidence in the national economy in40

general. All countries, except Qatar, have experiencedinternal debt. Bahrain registered increased debt from 51.8percent in 1993 to 69.9 percent in 1997. Kuwait reduced itsdebt by 21 percent in 1997, compared to 41.9 percent in1993. Qatar experienced external debt which reached 148.5percent in 1997, the highest debt in all GCC countries. TheUAE reduced its debt by 28.7 percent in 1997, compared to30.8 percent in 1993. Saudi Arabia and Oman are notsignificanthere.In an attempt to limit the effects of the recent decline inoil prices (which hit their budgets badly, in general, andcaused significant increases in their deficits, especiallyin Qatar) the GCC countries would have to adopt new monetaryand fiscal policies which may reduce the loss in oilrevenue. One policy would be to promote alternativeactivities through diversification of the economy, aiming atreducing its dependency on oil revenue. There are someeconomic measures, however, which could produce results muchfaster than the first policy, providing the government withnew sources of income. These policies are identified asfollows. Firstly, attract foreign investment via the stockexchange. Strong stock exchanges are fundamental to economicdevelopment. It would, therefore, be of importance to open41

these markets to foreign investors as the potentialopportunities presented by these stock exchanges appearpromising.Imposing taxes is the most popular financial instrument usedby present day governments. Due to the conservative Moslemnature of Gulf communities, <strong>Zakat</strong> would, however, be morefavourably received due to religious reasons. In this case(if the Gulf States were to impose <strong>Zakat</strong>) part of thegovernment's financial burden would be transferred to peoplewho would participate significantly in social securityprogrammes.The public availability of information would allow investorsto make their decisions from a solid basis. <strong>Unified</strong> <strong>Zakat</strong>regulation is important in this respect, as it would allowthe public to know, with confidence, that a specifiedpercentage of profit is going to <strong>Zakat</strong> in all the GulfStates. Also, that same regulation would encourage Mosleminvestors to invest in the GCC stock exchanges.2.3 Co-operation in the GCC StatesThe GCC states have more reason than any other group ofcountries to form a community, if not a union. To start42

with, they all share the same faith, Islam, and they allhave a common historical and racial background. GCCsocieties are also predominantly tribal. Indeed, equallyimportant is the fact that all GCC countries foundthemselves, in the space of a few years, moving from asubsistence economy to a rich economy primarily due to vastoil wealth. Political systems in the region are also similaras they are all ruled by royal or emir families. AlthoughKuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and the UAE have promulgated modernconstitutions, power still remains with the Emir (Rumaihi,1986). GCC countries share weak military capabilities, whichmakes them all quite vulnerable to the threats of morepowerful neighbours such as Iraq and Iran. In the 1960s and1970s all GCC countries felt threatened by expanding Arabnationalism as well as by the acceleration of religiousfundamentalism. Subsequently, internal as well as externalpolitical stability were the main reasons behind theestablishment of the Gulf Co-operation Council (Rumaihi,1986).Since the advent of oil, Per capita GDP increaseddramatically, and vast amounts of money were invested ininfrastructure, health, education and other social sectorsof the GCC countries. In brief, these countries moved from43

among the poorest countries in the world to among therichest in the world. However, all GCC countries suffer froma low population of nationals who are economically active.This amounts to around 20% in all GCC countries(Kapiszewski, 1998).Following the establishment of the GC Council, there wasconsiderable disagreement as to its priorities. Kuwait andUAE wanted to concentrate on economic and social issues,while Oman wanted more co-operation on military issues. Theother members, including Saudi Arabia, merely acted asmediators (Rumaihi, 1986).Although many strategic issues were not dealt with by theCouncil (because of internal disagreement), there are anumber of positive achievements. Among these is the freemovement of trade, the right of establishing business andwork, and the right of residence for GCC citizens. The othermajor step is the economic treaty signed in the 1980s(Kubursi, 1984). By 1995, this treaty had materialised intothefollowing:" Unifying customs duty and establishing a unified customssystem." Allowing companies free movement within GCC countries.44

" Agreement on linking the electricity network in the GCC." Allowing citizens of GCC countries ownership of estate orshares within any GCC country (GCC, General Secretariat,1997).However, there are many key strategic points that have notyet materialised. For example, the harmonisation ofdevelopment plans, oil policy, and a legal framework fortrade and investment in the region are all yet to beimplemented, despite the fact that these were part of theoriginal economic agreement (Kubursi, 1984). Among thepossible reasons behind this problem is the internaldivision and diversity of priorities between GCC members.This gives some insight into the possible difficulties thatcould arise during the attempt to harmonise <strong>Zakat</strong> accountingin the GCC. The first problem that might be expected wouldbe Oman. Oman's population and rulers are all Ibadhites, athird sect that is closer to the Sunnite than to the Shiite.Thus, as <strong>Zakat</strong> is closely linked to Shariah, it might wellbe expected Oman to object as it follows a different systemof jurisprudence. This is one of the main reasons why Omanwas not included in this study. The second problem couldcome from Qatar. Although Qatar is mostly Sunnite, thepolitical relations of Qatar and its neighbours have not1 45

een stable. This is especially so with Saudi Arabia andBahrain. Thus, it may not be constructive to include Qatarin a harmonisation project. Therefore, Qatar was alsoexcluded from the present study. The four selectedcountries, SA, Kuwait, Bahrain and the UAE enjoy excellentpolitical relations. Consequently, the success ofharmonisation is more likely within this group of four.Nevertheless, one possible source of difficulty might be thepresence of a large proportion of Shiite population whomight not respond favourably to any <strong>Zakat</strong> system imposed bythe Sunnites. This is why it is extremely important to carryout an empirical study, in which a representative samplefrom the four countries can be used for assessing theattitude of the population towards <strong>Zakat</strong> regulation andharmonisation.Another major obstacle that face <strong>Zakat</strong> harmonisation is thelack of regulation and implementation of zakat in the firstplace by the authorities in all of the GCC countries exceptSaudi Arabia. This issue is further discussed in the nextsection.46

2.4 An example of <strong>Zakat</strong> regulationAt present, there is no regulation of <strong>Zakat</strong> or personalincome tax in any of the GCC countries (except in SaudiArabia where <strong>Zakat</strong> is collected to a limited extent). Theimplementation of <strong>Zakat</strong>, in the early days of the presentSaudi dynasty, was not regulated by government, as peoplethemselves distributed <strong>Zakat</strong> to the poor according to theinstructions of Islam. However, although people know that<strong>Zakat</strong> is one of the five fundamental Islamic principles,many of them, due to their lack of education, were unawareof the principles on which it was levied. People oftendeclared their wealth to the religious leaders for them todecide how much should be given to the needy. They sometimessubmitted this amount to the Qadi (religious judge) of theirtown to spend it, on their behalf, on those who were in need(Jummjom, 1995).According to Yahya (1988) the first steps were taken towardsthe collection of <strong>Zakat</strong>. This followed the announcement thatlocal administrative boards were to be established in manycities and towns, like Hejaz and Al-Ahssa, to supervise boththe collection and distribution of the <strong>Zakat</strong>. In Najd, andother parts of the country in which the boards did notexist, the assumption is that people continued distributing47

their <strong>Zakat</strong> personally, on the advice of local Qodat. In1929, the Public Finance Agency was created and Al-Ahssasubmitted to the authority of this agency. In 1932 theagency was converted into the Ministry of Finance.The Department of <strong>Zakat</strong> and Income was established andauthorised to supervise the collection of income tax and<strong>Zakat</strong> by the Ministry of Finance decision No. 394, dated14/6/1951. It was originally established in Jeddah, andtransferred to Riyadh in 1970. It now has branches in majorcities of the country. In 1972 it became part of theMinistry of Finance. It is empowered to calculate and levythe <strong>Zakat</strong> without exception (Al-Sultan, 1997).IIn 1963 the money had to be submitted to the Social SecurityInstitution but, in 1965, this institution was dissolved. Itwas made known that the collected <strong>Zakat</strong> must be paid intothe account of the general treasury of the government. Also,the Ministry of Finance was ordered to open a separateaccount for this money so that it could be spent along withthe extra funds which the government assigns for socialsecurity purposes. In 1965, the Social Security Departmentwas established, according to Article 20 of the SocialSecurity Regulation. This department was created as part ofthe Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, with branch48

offices throughout the Saudi Kingdom. These offices obtainedinformation about the poor, from three sources (its ownbranches, the local governor or leading citizens andcharitable organisations in all Saudi cities), thusproviding the department with information about thefinancial condition of the poor (Attiah, 1986).Saudi and GCC citizens and wholly Saudi or GCC-ownedcompanies pay <strong>Zakat</strong> (a religious tax). According to thestatistics of the Ministry of Commerce, there are 76 Saudicompanies (6 real estate, 14 agricultural, 31 industrial, 6trades and 19 services). Their total capital is US$15,046.7million. Foreign companies, and companies with foreignholdings that have not obtained exemption under the ForeignInvestment Code, pay tax on their net profits or on theportion of net profits attributable to the foreignshareholding. Net profits are calculated by making allowancefor business expenses and depreciation, while capital gainsare also included in gross profits (Farhoud and Ibrahim,1986).Islamic banks and charitable organisations in the GCCcountries collect and distribute <strong>Zakat</strong> without a governmentmandate. Any person can give his or her <strong>Zakat</strong> to them withadvice from the donor on how to distribute it.49

2.4 SummaryThis chapter has reviewed the six member countries of theGulf Co-operation Council. The GCC was created with the hopethat the member countries would work together to face thelocal, regional and international challenges facing them.The Gulf region is unstable both politically and in terms ofsecurity. It is, therefore, important that a unifiedapproach be taken to deal with problems common to GCCstates. Additionally, the states have similar economies andmust integrate in order to face the other co-operationalmovements in Europe and America.The information presented here on the six countries revealsseveral common features. The first is that their economiesrely mainly on the oil sector. Industrial and agriculturalactivities are limited developments. The nationalpopulations, overall, are small and the proportion offoreign labour is high in most countries.All the countries are trying to develop and diversify theireconomies. At the same time, the governments of the GCCcountries have injected part of their income from oil intothe economy, in an attempt to increase the standard ofliving. This has resulted in a relatively high per capitaincome compared with the rest of the world. However, the50

future is uncertain. In trying to secure a constant flow ofrevenue, the situation of the GCC countries remainsunstable. <strong>Zakat</strong> appears to be one of the few financialmediums capable of stabilising the economic conditions intheGCC countries.51

ChapterthreePrinciplesofIslamicEconomics

ChapterthreePrinciples of Islamic Economics3.0 IntroductionThis chapter reviews some background principles to Islamiceconomics in order to underline the grounds upon which<strong>Zakat</strong> accounting is based. <strong>Zakat</strong> and riba are among themost important and controversial principles of Islamiceconomics. Any attempt at `Islamisation' of the economywill undoubtedly start with the imposition of <strong>Zakat</strong> and theprohibition of riba, before implementing other less clear-cut principles such as economic justice and welfare. Itwould make little sense, therefore, to discuss <strong>Zakat</strong>without first discussing and understanding the mainprinciples of Islamic economics.Islam contains a number of directives, which apply to theconduct of economic affairs (Gambling and Abdel-Karim,1991; Chapra, 1992; Kuran, 1992; Afzal-Ur-Rahman, 1980).These directives include moral and ethical norms both inproduction and consumption (fair wages, reasonable pricesand reasonable profits, moderate consumption, abstinencefrom the consumption of illegitimate goods and services).They also include other political and social directives52

(which, under Islam, are all guided by religion) such asGod's unity, obedience to the ruler, consultation, andsocialjustice.<strong>Zakat</strong> plays a major part in Islamic economic life andshould not be studied in isolation from the body ofreligious belief and economic theory that comprises Islamiceconomics. This chapter can be seen as an introduction,which contributes to a better understanding of <strong>Zakat</strong>.The chapter introduces the main features of the Islamiceconomic system. Islamic teachings cover spiritual, social,economic and political aspects of society. Inevitably,Islamic economics is based on a value system established bythe primary sources of jurisprudence in Islam. These arediscussed in section 3.1. Section 3.2 reviews somedefinitions of the Islamic economic system. This sectionprovides a brief description of the main sources ofeconomic thought in Islam. These are similar to the sourceof jurisprudence since they are both parts of theobjectives of Shariah. The principles of unity andbrotherhood are briefly outlined in Section 3.3. The maingoals of Islamic economics are discussed in section 3.4.These include some of the main foundations of Islamiceconomics, including wellbeing, social and economic justice53