The Central Bankers Report 2009

The Central Bankers Report 2009

The Central Bankers Report 2009

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

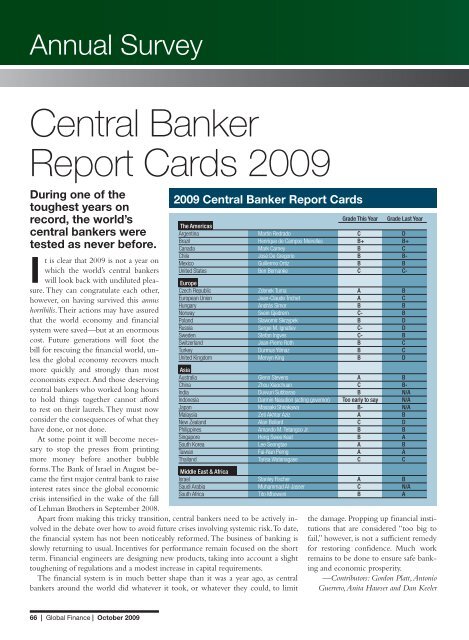

<strong>The</strong> AmericasArgentinaMartin RedradoGrade: CWhile Martin Redrado continues to suffer from the Argentineadministration’s lack of credibility on the financial front,particularly in underreporting inflation data, the central bankhead has recently taken steps that could lead to Argentina’sreturn to the international financial community. Working withfinance minister Amado Boudou, Redrado met with IMFWestern Hemisphere chief Nicolás Eyzaguirre to discuss stepstoward strengthening Argentina’s financial and monetary policies.President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner had sworn offthe IMF during her presidential campaign, saying she hopedher grandchildren would not even know what the multilateralagency was. <strong>The</strong> Redrado-Boudou team traveled to Londonto attend the Group of 20 ministerial meetings to discuss jointstrategies for tackling the global financial crisis. This is not tosay Redrado has gone rogue, as the administration maintains afirm grip over central bank policy. But he has recently introducedinitiatives that respond more to sound financial strategythan to political expediency. <strong>The</strong>se include steps to promotelocal credit markets in order to create a peso yield curve andboost domestic liquidity. Unfortunately, his boss is not likelyto loosen his reins anytime soon. In the financial chaos that isthe current administration, analysts are giving Redrado creditfor bringing some common sense to the table.BrazilHenrique de Campos MeirellesGrade: B+Henrique de Campos Meirelles’s prudent fiscal and monetarypolicies have helped Brazil navigate through the global economicdownturn. After curbing inflation through a series ofinterest rate hikes, the central bank has since cut the benchmarkSelic rate from 25% to July’s record-low 8.75%, contributingto the country’s economic recovery. Inflation fellfrom 17.2% in May 2003 to closer to 4% this year. Brazilis now expected to see year-on-year second-half <strong>2009</strong> GDPgrowth of as much as 8%, although analysts predict the economycould still shrink by 0.3% for full-year <strong>2009</strong>. Meirelles ismore optimistic and predicts a modest 0.8% expansion. Pollsshow consumer confidence growing steadily, so domestic demandshould fuel more robust growth next year. Despite hishigh grades at the central bank, Meirelles, who served brieflyin congress in 2002, may step down next April to enter thegubernatorial race for his home state of Goiás. President LuizInácio Lula da Silva, who publicly endorses Meirelles’s gubernatorialaspirations, would have to find a new central bankchief. Meirelles, Brazil’s longest-serving central bank president,would be a tough act to follow.CanadaMark CarneyGrade: BNo Canadian bank sought a governmentbailout or declared bankruptcy during theglobal financial crisis. <strong>The</strong> country’s conservativebanking regulations helped create aclimate in which Canada’s banks found iteasier to obtain funding than banks in many other countries.As a result, the Bank of Canada found it necessary to extendless liquidity in relation to the size of Canada’s economy thandid the United States and Britain. Mark Carney realized, however,that the strong Canadian dollar was offsetting the centralbank’s stimulative monetary policy, and he allowed the overnightinterest rate to remain at the effective lower boundary of0.25% for an extended period. Firmer commodity prices anda rebound in business and consumer confidence are encouragingdomestic demand growth at a time when inflation is undercontrol. As a result, Canada is looking forward to economicgrowth of 3% or better for the next two years. Carney remainsunpopular for his role in ending Canada’s income trusts—atax loophole—when he was at the finance ministry, but hedeserves credit for his sensible conduct of monetary policy.ChileJosé De GregorioGrade: BWhile José De Gregorio’s term was off toa bumpy start on account of problems inheritedfrom predecessor Vittorio Corbo,he has since shown his mettle by helpingChile remain among the region’s most stableeconomies. No Chilean bank has succumbed to the globalfinancial crisis, as the country already had a strong regulatoryframework and high banking standards. De Gregorio’s policiesare contributing to restarting the nation’s economy by supportingthe financial sector. <strong>The</strong> central bank’s actions haveincluded suspending issuance of central bank bonds throughyear-end and extending 90- and 180-day loans to banks atpreferential rates. While some countries are worried oversoaring inflation and weakened currencies, De Gregorio isOctober <strong>2009</strong> | Global Finance | 67

Annual Survey: <strong>Central</strong> Banker <strong>Report</strong> CardsEuropean UnionJean-Claude TrichetGrade: AAlways prone to plowing his own furrow,European Union central bankerJean-Claude Trichet has really shown hismettle in the past year. Turning a deaf earto the cacophony of calls for drastic interestrate cuts in response to the past year’s economic turmoil,Trichet carefully crafted the euro area’s monetary policy tocontain inflation while still pouring liquidity into its ailingbanking system. His “gradualist” approach is criticized bymany who complain that he is behind the curve in tacklingthe region’s economic turmoil, but, says Trichet, that is exactlythe point. By taking a measured approach and avoidingsharp, reactive changes in policy, the bank helps smoothout rather than amplify the peaks and troughs of economicactivity in the region. Predictably, as Europe’s economicfortunes appear to be reviving, Trichet is under pressure toshut down the ECB’s cheap money supplies, and, true toform, the central banker is unmoved. Wary of stunting therecovery before it is fully established, Trichet promises tokeep monetary policy loose for some time to come. He hasalso made a point of reminding policymakers around theworld that the financial system is still in need of significantreform—something that many might be forgetting as therecent fears of a global financial meltdown fade.SwedenStefan IngvesGrade: C-Until very recently, Sweden’s economywas whirring along nicely, fueled by asuccessful and internationally adventurousfinancial services industry and buoyanthigh-end consumer durables exports.<strong>The</strong>n the credit crunch hit, and after years of steady growthand low inflation, the country has found itself with a shrinkingeconomy, unpredictable inflation and a decidedly volatileexchange rate. As the IMF recently commented, “Havingsurfed the earlier global wave, Sweden has been hit hardby its crash.” Among those left gasping for breath on thebeach was Stefan Ingves, Sweden’s central banker. Seeminglyoblivious to the economic tsunami heading Sweden’sway, Ingves was still tightening monetary policy last fall,cranking rates up to a 12-year high of 4.75% in September.In October Ingves did an abrupt about-face and by theend of the year had slashed rates to 2%. Early this year thecentral bank admitted that Sweden’s economic pain wasfar worse than it had expected and halved rates to 1%. Bymid-July it had halved rates twice more to leave them atjust 0.25%. With growth still anemic, inflation well belowthe bank’s 2% target and unemployment set to peak at 11%,Ingves is now left with little option but to cross his fingersand hope for the best.SwitzerlandJean-Pierre RothGrade: BSwitzerland’s central bank has been muchbusier than usual of late. As well as dealingwith the imported problems from the globalcredit crunch and subsequent widespreadeconomic downturn, the Swiss NationalBank has been busy rescuing one of the country’s flagshipbanks, UBS. With characteristic understatement, Swiss centralbanker Jean-Pierre Roth described the purchase of a 9% stakein UBS as helping the embattled bank with its “credibilityproblem.” Not long afterward, the SNB was dealing with acredibility problem of its own as it admitted the country’seconomy was in recession and facing the specter of deflationfor the full-year <strong>2009</strong>. By March this year the bank hadslashed interest rates to near zero, was pumping liquidity intothe system and had risked global opprobrium by interveningin the forex markets to bring down the soaring franc—butthe outlook was as gloomy as ever. Roth has grumbled beforethat the franc’s status as a safe-haven currency limits the efficacyof the SNB’s monetary policy, and recent events haveclearly borne this out. Until the global flight to safety trulyabates and investors start selling their francs as they seek higher-yieldinginvestments elsewhere, Roth will be saddled withan overvalued currency and an underperforming economy.TurkeyDurmus YilmazGrade: BTurkey’s central bankers always appear to belocked in a battle with inflation, and DurmusYilmaz is no exception. His record onthat front is not exactly stellar, as inflationconsistently overshot the central bank’s targetsfor several years. This past year, though, Yilmaz appearsto have hit his stride. Confident that the global slowdownwould squeeze Turkish inflation down sharply, Yilmaz embarkedon a dramatic round of interest rate cuts in Novemberlast year. By February he had slashed rates from 16.75% to11.5%, following up in April and August with further cutsthat brought the bank’s key rate to 9.5%. Gratifyingly, Yilmaz’sconviction that inflation would subside despite the sharp ratecuts proved correct, and he now believes that by year-endit will have sunk to 5.9%, while there are already signs thatTurkey’s economy, boosted by the lower interest rates, couldbe emerging from the slump. By the end of 2010, Yilmaz ispredicting inflation will be down to 5.3%. Both figures arecomfortably below the bank’s upper target levels. Yilmaz deservescredit for his outspoken efforts to persuade the Turkishgovernment to exercise fiscal restraint. He has also urged the72 | Global Finance | October <strong>2009</strong>

Annual Survey: <strong>Central</strong> Banker <strong>Report</strong> CardsChinaZhou XiaochuanGrade: CLast year the People’s Bank of China(PBOC) appeared to be reluctant to tightenthe monetary policy reins. This year, however,it appears to be slowly starting to turnthe screws. <strong>The</strong> PBOC has made it clear itneeds to keep a watchful eye on the spate of new lendingactivity by banks, which in the first few months of this yearwas almost three times the 2008 level. New lending has hadthe desired effect in terms of propping up spending and haskept projected real GDP growth for this year and next at abuoyant 8%. However, there are concerns that the economymay overheat and non-performing loans (NPLs) will increase.With new loans still increasing in June, banks did not appearto be heeding the PBOC’s call for restraint. It is questionablewhether the bank can forestall a credit bubble at thesame time as maintaining its relatively loose monetary policystance. <strong>The</strong>re is also the nagging question about the valuationof the renminbi, which, according to some economists,is undervalued by 15%-25%. With exports driving the councountry’sleaders—in no uncertain terms—to implement thestructural reforms necessary to bring Turkey in line with theEU accession criteria.United KingdomMervyn KingGrade: BA year ago it was touch and go whetherMervyn King would remain as the governorof the Bank of England. In the end hemanaged to swing another five-year termbut not before he was hauled over the coalsfor failing to save the United Kingdom from recession, failingto keep inflation below target and failing to prevent NorthernRock from failing. What King’s critics failed to appreciatewas that all those failures were linked, and it would havebeen practically impossible for King not to fail—at least onone count, if not all. Luckily for King, it turned out that theUK was the bellwether for the developed markets generally,most of which were diving into their own death spirals beforethe ink was dry on King’s letter of reappointment. Perhapschastened by allegations that King tended to do too little, toolate, the bank then lurched ahead of the curve, joining thevanguard of central banks driving interest rates down to nearzero and indulging in so-called quantitative easing. <strong>The</strong> bank’sbelated boldness appears to be doing the trick. It now predictsthat growth will recover in 2010 while inflation will remainaround or below the 2% target for some time to come.Asiatry’s continued economic growth, though, China is unlikelyto want its currency to appreciate.IndiaDuvvuri SubbaraoGrade: BIndia expects to turn in a chunky 6.7% increasein GDP this year, but all is not rosy.Inflation is stubbornly refusing to budgefrom its 6% average this year, and there areconcerns that the central bank’s efforts tocombat the credit crunch by boosting liquidity will only addto inflationary pressures. Duvvuri Subbarao, who took overas India’s central banker last year, has been pumping liquidityinto the system by reducing the cash reserve and statutoryliquidity requirements for banks, as well as providing a specialrefinancing facility for banks. <strong>The</strong>se measures appeared to haveworked, increasing the availability of credit but not to excessivelevels. However, government stimulus packages have raised thefiscal deficit, which is projected to reach 6.8% in <strong>2009</strong>-2010.Subbarao is mindful of the need to prevent excessive governmentborrowing while also ensuring ample liquidity is availableAustraliaGlenn StevensGrade: AWith GDP set to contract only slightly in<strong>2009</strong> and inflation predicted to hit a modest1.6% for the year, it looks like GlennStevens’ policy of “aggressive” loosening ofthe overnight cash rate has worked like acharm. Some observers suggested that Stevens overreacted tothe global and domestic downturns, having slashed rates by425 basis points between March 2008 and April <strong>2009</strong>. However,he is one of the few central bankers who both spottedthe crisis on the horizon and actually did something about itbefore it was too late. With the key interest rate now at 3%and inflation prospects looking remarkably benign, the bankclaims it has room for further cuts if necessary. Recent data,however, suggest that the next move is more likely to be upthan down. <strong>The</strong> bank admitted it was surprised by the recentsigns of recovery and is ready to tighten policy if it senses thatthe economy really is out of the woods. Slashing the cash ratehas also had a positive impact on Australia’s household debtproblem. In December Stevens indicated that rate cuts meantthat “the fall in the household sector’s gross debt-servicingburden [would] be almost 3% of household income.”74 | Global Finance | October <strong>2009</strong>

Annual Survey: <strong>Central</strong> Banker <strong>Report</strong> CardsMalaysiaZeti Akhtar AzizGrade: AMalaysia’s economy has suffered over thepast year, with GDP contracting 6.2%year-on-year in the first quarter as thecountry’s export market suffered from thefall in global demand. At the same time,though, increases in food prices have tailed off. <strong>The</strong> centralbank forecasts average annual inflation to settle between1.5% and 2% this year. As inflation has fallen, Zeti has adopteda measured approach to loosening monetary policy, with150 basis points in rate cuts from last November to Marchthis year. For the moment, she is holding off any furthereasing as growth is expected to return in the latter half ofthe year. <strong>The</strong> bank’s key rate is expected to remain at 2% forthe remainder of the year and into 2010. Meanwhile, Zetihas turned her focus to other monetary policy measures forstimulating growth: ensuring that the central bank’s rate cutsare being passed on to borrowers and that there is ampleliquidity swilling around in the system for companies thatneed refinancing. However, she needs to remain vigilant toensure that promoting bank lending does not generate morenon-performing loans.to meet private sector demand, and he has demonstrated hiswillingness to tighten and loosen monetary policy as needed.While adopting a more accommodative stance in the wake ofthe financial crisis, Subbarao has hinted that his “expansionarypolicies” could be reversed in the near future as the economyshows demonstrable signs of improvement.IndonesiaDarmin Nasution (acting governor)Grade: Too early to sayBoediono’s tenure as governor of Bank Indonesia was shortlived, as in May, just a year after he took office, he was acceptedas a candidate for vice president of Indonesia. However, he isno doubt responsible for recent gyrations in interest rates atthe bank. Last year, with inflation soaring, the bank pushed uprates to 9.5% before instituting a series of rate cuts as inflationarypressures declined. By the end of the first half of this yearinflation was down to 3.7% despite the 3 percentage pointfall in central bank interest rates. Cognizant of the inflationaryeffect of lower interest rates, the central bank predicts thatprice increases will grow next year and has already announcedthat it expects to tighten monetary policy in the near future.While inflation seems under control and GDP is still expectedto grow this year, economists say the rate cuts have had littleimpact on bank lending, with bank credit growth declining.However, some analysts have revised upward their forecasts forreal GDP growth this year to 2.6% following a surprising 4.4%year-on-year growth in real terms in the first quarter. At itsSeptember meeting, the bank opted to keep rates unchangedat 6.5%, citing its belief that the appreciating currency is offsettingthe slight upward trend in inflation.JapanMasaaki ShirakawaGrade: B-Masaaki Shirakawa took the reins at theBank of Japan at a difficult time. Afterspending years battling deflation, the banklast year suddenly was facing the threatof inflation. With interest rates effectivelyat zero, the bank had plenty of scope to tighten monetarypolicy, but for one thing: Growth was slowing at the sametime, and the last thing the bank wanted to do was to accelerateJapan’s slide into recession. In the end, it did practicallynothing, and, as it turns out, it appears that Japan’s doughtyeconomy is going to pull through. According to the bank,if general global growth resumes and there are no significantshocks to the domestic or foreign markets, Japan shouldreturn to a normal economic environment with steadygrowth and stable prices. Under the current circumstances,that is an awfully big “if,” and Shirakawa knows it. He admitsthat business investment and domestic consumption remainweak and that unemployment is worsening. He also knowsthat preventing a “deflationary spiral” is the biggest battle hefaces, but he is hopeful that providing banks with sufficientliquidity, combined with a low-interest-rate environment,will have a positive impact on corporate funding and thewider economy in general.New ZealandAlan BollardGrade: C<strong>The</strong> Reserve Bank of New Zealand hasdemonstrated its resolve in its fight againstthe recession. From July last year up untilApril this year, central banker Alan Bollardhas considerably loosened monetarypolicy, slashing rates progressively from 8.25% to 2.5%. ByJune it appeared the cuts were working, as a slight uptickin household spending and investment prompted the bankto hold rates steady at 2.5%. Bollard believes the reboundin spending may not be sustainable, though, given that unemploymentremains high and households are nursing highlevels of debt. With risks to economic activity remaining onthe downside, Bollard may need to ease monetary policyeven further. <strong>The</strong> outlook is not helped by a recent appreciationof the New Zealand dollar after it had fallendramatically in the wake of hefty interest rate cuts. Bollardwill need to take decisive action when it comes to furtherrate cuts, which he has not ruled out. He is treading a76 | Global Finance | October <strong>2009</strong>

Annual Survey: <strong>Central</strong> Banker <strong>Report</strong> CardsThailandTarisa WatanagaseGrade: CThree years into the job, Tarisa Watanagaseappears to have developed considerableconfidence in her role as Bank of Thailandgovernor, having raised the ire of thegovernment last year by increasing interestrates at a time when political leaders were trying to stimulateeconomic growth. This year, however, Watanagase’s stancehas been more accommodative, with the policy interest ratebeing cut from 3.75% last December to 1.25%. Watanagasewill be frustrated that the cuts have had little impact on thereal economy in terms of loan growth. No surprise, then,that she has kept rates on hold as she waits to see if futureeconomic data provide some glimmer of hope that the cutshave filtered through. However, with rates so low, she has leftherself little room to maneuver. For the first time since the1997 Asian economic crisis, the Thai economy is expected toshrink—by between 3.5% and 4.5% this year—with growthreturning in 2010. Some encouraging signs appeared in thesecond quarter with rising exports and lower unemploymentfigures. However, private consumption and investment stillremain at low levels.Middle East & AfricaSaudi ArabiaMuhammad Al-JasserGrade: CMuhammad Al-Jasser was named in February <strong>2009</strong> to headthe conservative Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA), thekingdom’s central bank. <strong>The</strong> former deputy governor was wellschooled in SAMA’s strict regulatory policies. Long used tocautioning banks about the dangers of speculation, he facedan entirely different problem when commercial bank lendingseized up in the face of a weak economy. Like other centralbanks around the world, SAMA cut rates. Commercial bankswere afraid to lend, however, in part because of worries aboutthe problems at two family-owned conglomerates, Saad Groupand Ahmad Hamad Algosaibi & Brothers, which announcedplans to restructure billions of dollars of debt. SAMA was silentabout the extent of the problem, which may have exacerbatedthe lack of trust in a system that lacks transparency. Al-Jasserwas right to maintain the riyal’s peg to the dollar during theseuncertain times. However, he may have undermined efforts toadvance monetary union in the Gulf with his insistence thatRiyadh host the forerunner of the Gulf Cooperation Council’sproposed central bank. <strong>The</strong> move was not well received inthe United Arab Emirates, the second-largest economy in theGCC, which opted to pull out of the project.South AfricaTito MboweniGrade: BTito Mboweni’s days are numbered as governorof the Reserve Bank of South Africa.Gill Marcus, chairperson of Absa, one ofSouth Africa’s leading banks, will take hisplace come November 9. If former A-gradewinnerMboweni can be faulted, it is for sticking to a tightmonetary policy to combat inflation at a time when the economywas clearly faltering. While Mboweni was reappointed asReserve Bank governor before indicating his desire to leave thepost, he likely would have clashed eventually with Jacob Zuma,the populist leader of the African National Congress, who waselected president of South Africa in April. Marcus could abandoninflation targeting to boost the economy, but her bankingexperience and former positions as a deputy governor of theReserve Bank and deputy minister of finance have reassuredinvestors. <strong>The</strong>y remain nervous, nonetheless, that Mbowenimay have failed in his goal of preserving the unquestioned independenceof the central bank.IsraelStanley FischerGrade: AFor a small, open economy like Israel,the central bank needs to make surethat an overvalued currency is not negatingthe effects of low interest rates.Stanley Fischer implemented an aggressivecurrency intervention policy at the Bank of Israel thatpushed the country’s international reserves in July <strong>2009</strong> upto a record $52 billion, double the level of a year earlier.Fischer, former deputy managing director at the InternationalMonetary Fund, saw the global recession comingand helped to limit its effect on the country’s exports bybuying dollars and selling shekels to restrain the currency’sadvance. In August <strong>2009</strong> the central bank ended its dailypurchases of dollars, which had reached $100 million ona regular basis, and announced that it would continue tointervene to counteract disorderly market conditions. <strong>The</strong>element of surprise helped to discourage hot-money inflows,with daily intervention of as much as $500 millionat times. <strong>The</strong> Bank of Israel surprised the markets a secondtime in August when it became the first major central bankto raise interest rates since the financial crisis worsened inSeptember 2008. While the quarter-point increase from arecord-low 0.5% came sooner than most analysts expected,it struck a balance between the need to control inflationand to support the country’s budding economic recovery.78 | Global Finance | October <strong>2009</strong>