Reconstructions - Displayer

Reconstructions - Displayer

Reconstructions - Displayer

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

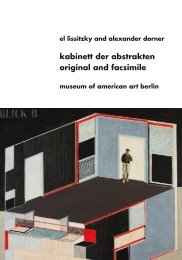

<strong>Reconstructions</strong>Cross-section of the Roman theater after reconstruction, Teatro de Sagunto, Giorgio Grassi, 1986–1994, Sagunto.What are the reasons for reconstruction? How does reconstruction alter the use and meaning of the heritagesite? Which roles do the site and, more importantly, the imprint of the architecture on the site itself play?To what extent must a reconstructive design comply with additional urban development? In 1985 GiorgioGrassi and Manolo Portaceli were awarded the contract to restore the Roman theater in Sagunto, Valencia.By the time the project got underway many restorative measures and alterations had already been carriedout so that the ruins looked like those of a Greek theater. Grassi and Portaceli reconstructed the theaterbased on well-maintained documentation and the manipulated remains. At the heart of their work was thedesire to make legible the idea of the Roman theater once again. Since Spanish historic preservation lawswere not adequately observed, it was decided on January 19, 2008 to tear the reconstructed Roman theaterdown within the next 18 months. Five years ago, when the reconstruction of Walter Gropius’ Director’sHouse in Dessau was up for discussion, Guillaume Paoli used the situation as an opportunity to moreclosely examine the notion of reconstruction. Here form is crucial, as with many reconstruction projects, butalso in Dessau the question of use still remains unanswered. However, not only use but also tourismand the reception of history are aspects that aren’t taken into enough consideration by the builders of fallenmonuments.<strong>Reconstructions</strong> <strong>Displayer</strong> / 233

Giorgio Grassidifferent, even very different conditions, are in realitymore prominent. Faced with these interventions, wecontrary, characterizes much of Roman theatrical pro-reconstruction projects. Another consequence thatchose to eliminate those that led to a distorted readingduction when compared with that of the Greeks. Whichflows from these assumptions is that the fragmentof the ancient artifact, while on the contrary preservingonly confirms the primacy of the building’s architectureReconstruction In Architecture(whether archaeological or not)—and that is exactlywhat a monumental ruin is—has no architectural valuethose that did not conflict with its reconstruction ‘asit was:’ essentially, even if they were the product of aover every other aspect of the theater in Rome.My relationship with architecture and its practice isin itself. An architectural fragment is always merely partbelated Ruskinian interpretation of the ruins, they tooThere is a curious and revealing anecdote that is worthbased on the (admittedly schematic) idea of an archi-of a whole, part, that is, of a work that was designed tonow belong to the building’s history, and to eliminatementioning in this context. At a conference held bytecture founded on the specificity, autonomy, andexpress itself in all its completeness as an architecturalthem would have meant destroying a piece of that his-E. Souriau in Paris in the 1950s on the theme of ‘Archi-substantial unity of its experience in time. And this inwork. And as such, the fragment only has value as parttory unnecessarily.tecture et Dramaturgie,’ among the various influentialthe sense that for me, that experience is exclusivelyof that work.figures who spoke were Le Corbusier and Louis Jouvet,accountable to itself, to its own materiality and physi-With respect to the Greek theater, the Roman theaterrespectively the most famous architect and most influen-cality as an autonomous and independent fact, andIn this sense, the original ruins of the theater of Saguntowas something entirely new and absolutely extraor-tial man of the theater of the time, both of whom spoketo its essentially self-referential character, all of whichwere the point of departure for our project—they weredinary. Its objectives were quite distinct, and henceon the topic of the theater as architecture. The peculiarmakes it, precisely, an experience that is fundamentallyliterally the stones on which we built. And this we did —inthe result could only be a different, indeed completelything—but not that peculiar on closer examination—isunitary in time.the first instance and in the most general sense —withdifferent, thing. Whereas the Greek theater is above allthat Le Corbusier argued that the entire meaning ofthe exclusive aim of restoring to those ruins what for usits site, the Roman theater is exclusively its form—athe theater lies not in its site but in the theatrical actionThat this is the case is demonstrated by every workwas their sole legitimate task, to bring to light the trueform that is capable of adapting to and imposing itself(for example, he describes the campielli in Venice asof architecture worthy of the name. But every suchform of the Roman theater of Sagunto.upon any site whatsoever. It is this absolute primacy oftheatrical sites), whereas Jouvet attributes to the physicalwork also attests to the fact that it is conditioned bythe form in the Roman theater that led, indeed virtuallystructure, to its unique and remarkable space, the deep-or even dependent on those that preceded it, evenAll the rest—everything that can be said about the ruinsobligated us, to reconstruct Sagunto.est and most authentic meaning of the theater, the verywhen it seems to have superseded or refuted them. Allas such, about their value as a historical memento,special bond that links the spectator to what takes placehistorical experience of architecture is based on thiscollective or individual, about the evocation of the past,While there are innumerable more or less well preservedon the stage (‘Whether ancient or modern, it is in thesepremise: the uninterrupted bond with ancient architec-the myth of the origins, etc., all of which in fact belongsRoman theaters scattered throughout the vast areadeserted structures [arenas, amphitheaters, or theaters],ture from the Renaissance on (in this connection, it isexclusively to the realm of intellectual reflection on, orof the former empire, there are very few (Aspendos,as one suddenly enters them and is penetrated by theirworth recalling the beautiful words of Adolf Loos: ‘Forsentimental identification with, the world of the ruins —hasSabratha, perhaps Basra) that are still in a position tostrange emptiness and silence, that one can approach anas long as humanity has felt the greatness of classi-nothing to do with the ruins themselves or the architec-restore to us the specific quality of the Roman theaterauthentic idea of the theater.’).cal antiquity, the great architects have been boundtonic fragment as architecture.as architecture.together by a single common idea. They think: the wayIt certainly was not our aim in reconstructing SaguntoI build is the way the ancient Romans would also haveOur reconstruction effort was first of all based on theThe idea of the Roman theater is entirely containedto propose a model solution, something that mightbuilt. We know they’re wrong. Time, place, purpose,original ruins of the theater of Sagunto, and then,in its architecture, in its unmistakable volume and theteach others ‘how it’s done,’ something that mightclimate and milieu thwart this ambition. But wheneverof course, on the type of the Roman theater (perhapsdizzying space of its enclosure, in its artificiality, whichserve as an example for other projects, something thatarchitecture is pushed further from its greatness bythe type of public building defined more preciselyis so obvious, so open and unabashed with respectmight be repeated.the small ones, the ornamentalists—as happens againand canonized by the entire experience of Romanto its various objectives, so in keeping with its practicaland again—the great architect is there to lead it backcivic architecture). We built a theater ‘in the man-purpose and subsequent development (the Renais-We had identified a few specific conditions in thetoward antiquity.’).ner of the Romans,’ and we naturally did so with thesance theater and the teatro all’italiana). Even thetheater of Sagunto that seemed to us to be necessarymeans, the culture, and the eyes of our time (withpolitical idea of the Roman theater, its civilizing as welland sufficient for its reconstruction in keeping with ourWhat was said above naturally has consequencesour own eyes): thus, it is precisely a Roman theateras conquering function in such a vast territory, isaims (the completion of its volume within the contextprecisely for the subject of reconstruction. The firstbuilt today.entirely contained in the canonical forms of the physicalof the city of today as well as that of its internal spaceand most obvious consequence is that for me, therestructure of the theater.on the basis of what its remnants had to offer beforeis no significant difference between construction andIn the 1960s and ‘70s, Sagunto underwent interventionsour intervention). These included the state of the ruins,reconstruction. If the relationship to historical experi-whose object was not the Roman theater but its ruins,The extraordinarily innovative character of the Romanwhich had been irreversibly compromised by crudeence is a necessary and inescapable condition of aand whose aim was clearly to develop them into atheater as physical structure contrasts—and not with-mimetic interventions, and the relationship betweenproject, then all projects—even if they proceed fromspectacle in their own right, to make them showier andout reason—with the modest inspiration that, on thethe ruins and their surroundings, which had fortunately234 / <strong>Reconstructions</strong> <strong>Displayer</strong> Giorgio Grassi / 235

preserved the conditions of the original structure vis-àvisits site: the theater’s ruins separated the area of theforum, which lay above it, from the ancient city on thehill below it.Taking as our point of departure the idea of architectureand of the relationship between project and historicalexperience described above, our aim, right from thestart, was to put that idea and working hypothesis intopractice as directly and explicitly as possible in theirmost didactic form, so that the procedure could emergeclearly and unambiguously. The result and the resultalone would justify the procedure.Only the realized project would show whether or not wehad been able to establish a coherent and positiverelationship with that extraordinary moment in thehistorical experience of architecture that was preciselyRoman architecture. It alone would show whether ornot our project had succeeded in re-establishing that‘alliance with the ancients’ that we find in all the greatarchitectural works of the past, without giving up thespecificity of our training and our affiliation with our timebut on the contrary binding ourselves to it even morefirmly; without, that is, giving up the freedom to expressourselves with the means at our disposal today, withoutconcessions or expedients of any kind.Why perform a comedy by Plautus or a tragedy bySeneca today? Why do so if we have no idea ‘how’they were performed at the time? Our words, ourgestures, our intonation, even our technical means—masks or microphones, natural or artificial light, etc.:everything separates us from them; everything is different.The means we use to express ourselves are ourmeans; they are those of today—and they could notbe otherwise. Do we then lose something of those textsby performing them? Or on the contrary, isn’t that theonly way to rediscover what unites us and what permitsus to recognize and see ourselves reflected in them?And if that is the case, why should we refrain fromdoing so, since the only legitimate way that we haveto perform those texts is our own?But if that is the case, then why is there such an outcrywhen there is talk of reconstructing an ancient monument?And why should we refrain from doing so, if theonly legitimate way that we have to reconstruct suchmonuments is our own?The result in the case of Sagunto may or may not be toone’s liking (that is none of my business), but it cannoteasily be claimed that it constitutes a perversion of theruins, a misunderstanding of their meaning and material,or an improper use of them, or that something theyformerly possessed has been taken away from themand lost (isn’t that just like maintaining that Plautus cannotbe performed today because we don’t know how itwas done at the time?).The Roman theater is a well-defined architectonic type;the period of its construction in the Roman world didnot last long—little more than a century; but its vitalrole has never ceased (the process of developing anddeepening the virtuality that was preserved by thearchitectonic type of the Roman theater has never beeninterrupted). It has reappeared whenever the theaterhad need of it again: in Italy in Parma and Vicenza; inSpain in the corrales; in London in the Globe; and soon through the teatro all’italiana and its extraordinaryspread throughout the world. Whenever the theaterdecided to take up residence at a site, it took shape inthe form that, although it was the first, already hadwithin itself everything it needed to adapt withoutchanging, without altering what, for Louis Jouvet, isthe very meaning of the theater of all times and places:precisely its form, which is always new but in realityalways the same.As for the Berliner Schloss, the situation is obviouslycompletely different. For example, one would be hardpressed to maintain that it is a typical castle, a typicalexample of a castle among the many in Germany orEurope, that is, that it reflects a distinct and recognizablearchitectonic type. This is because in reality thereis no determinate type of the castle (in a certain region,for example, and a certain time). Moreover, the BerlinerSchloss is exquisitely composite; its construction wassubject to a diverse, indeed extremely diverse, arrayof influences over time (due to the clients, the architects,changing economic conditions, etc.).In other words, unlike the Roman theater of Sagunto(and it is surely no accident that with very few exceptions,Roman architecture is an architecture withoutindividual architects), the Berliner Schloss representsonly itself. And from the point of view of its architecture,that makes it unrepeatable, practically but alsotheoretically.The only alternative would be to construct a copy ofit—an exact copy, as similar to it as possible in itsgood points as well as its bad. That is what was done,for example, with the reconstruction of the campanileof San Marco in Venice after its sudden collapse, anapproach that in this case was justified by the desire torestore the architectonic composition of the square.It is also what was done with the reconstruction of thehistoric city center of Warsaw; in that case, by contrast,it was justified by the powerful ideological andpolitical motivation to put the war in the past. In bothof these cases, however, the architectonic value ofthe reconstruction was clearly nil, since neither of thetwo responses reacted in any way to the fact that theywere nonetheless still responses at the level of theirarchitecture.Both of these theoretical motivations are at work in thereconstruction of the Berliner Schloss. The ideologicaland political one is certainly the more powerful, evenif that of the architectonic restoration of the Lustgartenis obviously the one it is easier to win acceptance for.On the other hand, treating monuments as if they weremerely political symbols is not just simplistic but politicallychildish; and it is also always an act of gratuitousviolence. That is what the GDR did when it destroyedthe Berliner Schloss and built the Palast der Republikin its place (a banal example of contemporary architecture,perhaps unworthy of being preserved but animportant piece of history nonetheless, which does notvanish painlessly). But it is also what the city is preparingto do today in an effort to ‘put things back in theirproper place,’ as the saying goes—formally in theirproper place, and yet in the process obliterating apiece of the city’s history, which belongs to it in spite ofeverything.In fact, I believe that the point of view of the city and itshistory is the proper one from which to view the issueof the reconstruction of the Berliner Schloss. The castleis an important part of the city’s history, and in thissense it is its mirror. Whatever is ultimately done(whatever is constructed, destroyed, or reconstructed),the castle will continue to represent that history faithfully.We must acknowledge this and accept it as a factthat is independent of us, and decide if it is our tasktoday to make a futile attempt to blot history out byreconstructing the castle in an uncritical—deliberatelyuncritical—manner, or to highlight the special qualitythat the building possesses by dint of having for so longbeen a privileged witness to the history of the city.I realize that this is something with which architecturehas very little to do, or at least on an issue like this one,it is not in a position to express itself using its nativemeans. Nevertheless, architecture can draw from thisissue indications, suggestions, but also concrete elementsfor a critical reconstruction that is as valid as itis necessary, helping to ensure that the new castle’sforms are able to recount those changing and dramaticevents which they are no longer in a position to bearwitness to directly.What, then, should we expect at this point from areconstruction of the Berliner Schloss? Certainly not abuilding that is proud of itself and proud to be back asif nothing had happened, the result of a hasty decisionto do whatever it takes to ensure that, in the end, thebuilding is in its place again and shown off to its bestadvantage. Nor, however, should we expect a largecommercial and cultural center on an internationalscale, a cultural hub, a convention center, etc., with236 / <strong>Reconstructions</strong> <strong>Displayer</strong> Giorgio Grassi / 237

all the amenities, that is, a large and complex structurenot long ago they stupidly tore down, convinced thatGuillaume Paolias well in a book or on a souvenir. There’s no pointthat could not possibly stand in any plausible relation-they would be able to replace it with something morein making a pilgrimage to a fake.ship with a castle, be it old or new, and especially notsuitable and appropriate to the times.with a castle disguised as the old Berliner Schloss. Noreven—to return to a hypothesis already tried in its timeWith a similar degree of faith in their resources and aA New View of the PastIs the term ‘tourist’ even applicable to imitation touristattractions? Aren’t tourists the ultimate authenticity-in provisional form—a system of stage sets designed,certain amount of thoughtlessness and presumption,DISPLAYER It seems a specter is haunting architec-seekers?on the one side, to delimit the Lustgarten ‘as it was’they are now preparing to reconstruct the Berlinertural Germany: reconstructivism. Buildings long thoughtYes, probably the term ‘post-tourist’ is more fitting—a(but are we sure that that’s the best solution for theSchloss, with stage sets on two sides to delimit theto be extinct have been and are being built anew: theneologism coined by the Bauhaus cultural theoristLustgarten?), and, on the other, to hide behind them anLustgarten and the Kupfergraben, additional sets toBraunschweiger Schloss; the Potsdamer Stadtschloss;Regina Bittner. Post-tourists are the ones whoentire series of more or less necessary functions.define the internal space of the Schlüterhof, and behindin Berlin, the Alte Kommandantur, the Bauakademievisit replicas, reconstructions and copies—after all,and in the midst of this improbable system of stageand the Stadtschloss; in Dresden, the Frauenkirche.most tourist attractions are replicas somehow, atIn my opinion, none of these responses is worthy of thesets virtually all that the area of the old castle canHow do you explain the success of reconstructivism?least in part. But why rebuild these inauthentic sitescity of Berlin, neither of its new situation nor much lesspossibly hold, which is necessary to finance the costlyGUILLAUME PAOLI A new view of the past seemsin the same location when you could easily placeof the city ‘as it was’ before the demolition. I believe theoperation.to have arisen, and the reason is that our view ofthem somewhere else entirely? Of course, todayonly viable alternative is the one that has already beenthe future has changed. There are no more avant-lots of reconstructions are virtual; you don’t evenmentioned, that is, to replace the old castle with a newAnd all of this despite the fact that the Berlinergardes and no more hopeful prospects; this is truehave to travel anymore. For a few weeks now it’sone. A castle for Berlin on the same site, not boundSchloss—that old, exaggerated, and unwieldy struc-in all areas of life. And with our perspective onbeen possible to take a virtual walk in the Romanto the old one except by the fact that it too attemptsture—is not at all the unique and irreplaceable piecethe future we also change our perspective on theForum on the internet, which you can’t do in real life.to present itself as a castle, not necessarily bound bythat it is said to be (with all due respect for Schlüter,past. The past becomes a retrospective prophecy.Post-tourists could be people who stay at homethe forms or even the dimensions of the old one, aEosander, etc., what was lost was certainly no master-The process of reconstruction begins at the pre-and create their trips in cyberspace. That fits rightcastle that, while faithful to the aim of reconstruction,piece, at least in my opinion). It was a freestandingcise moment when the past is seen as a propheticin with global warming and the energy crisis, too:also assumes the task of responding to the Lustgartenstructure capable of holding its own beside the manyconstruct. The paradox is that while reconstructionYou save money, you stay home, and you can dis-of today, the elements of whose composition are theother ambitious freestanding structures in that areapromises on one hand to revitalize the past, on thecover the world without emitting CO 2 .same as they were when Schinkel built his museum,with the sole exception precisely of the castle. A Berlin(including the cathedral, the Nationalgalerie, thePergamon, the Bode, etc.), but certainly not besideother it is an annulment of history. The devastationsand upheavals of the twentieth century are simplyDestructionscity castle constructed today, with today’s eyes andthe Altes Museum, which faced it and which seemserased.Are there reconstructions you consider wise ormeans (for that matter, is there an alternative?). Frankly,to have attempted to ignore its unwieldy neighbor inunwise? What do you think of the reconstruction ofan almost impossible challenge, in my view at leastits own design. It was a building, one imagines, thatHow do you rate the influence of tourism on recon-Dresden’s Frauenkirche, for example?(however, one in which more than a hundred architectsSchinkel would have preferred not to have before himstructivism?The critical factor here is the political aspect. Thewere involved). A challenge posed to contemporarywhen designing the Lustgarten.Highly. Tourists are people who are always lookingFrauenkirche was destroyed by Anglo-Americanarchitecture by an old monument that the Berlinersfor authenticity, especially when it’s a matter ofbombs, and thus for the ‘good cause’ of democracy.themselves perhaps never particularly liked and thatThe text is based on questions via e-mail, Milan, Marchseeking out contrasts to home. A good example ofThe reconstruction would have had fatal under-they may even have almost forgotten, a monument that05, 2009.touristic reconstructivism is the Goethehaus intones of revanchism had it not been financed inFrankfurt, which was rebuilt in the fifties. But in thispart by English contributions—as reparation, so toconnection I also think of the caves of Lascaux,speak. Not so the Berliner Stadtschloss. Becausewhich were closed because the hordes of visitorsit was demolished for the ‘bad cause’ of socialism,grew too big, only to be reconstructed a shortthis symbol of Prussian militarism can be restoreddistance away from the original. Millions of touristswithout a qualm. Some graffiti on the destroyedsee these cave paintings, and many have no ideaPalast der Republik made the message quite explicit:they’re standing in a fake. This raises the question:‘The GDR never existed.’Why were the copies created just a few kilometersaway and not somewhere else entirely? I haven’tWhat do you think of the idea of rebuilding Walterbeen to the caves myself; I could look at them justGropius’s Direktorenhaus?238 / <strong>Reconstructions</strong> <strong>Displayer</strong>Guillaume Paoli / 239

First of all, I don’t think Gropius would have been infavor of rebuilding it. I considered the subject fouryears ago, when the calls for reconstruction becameinsistent. I incline to the proposal made by FilipNoterdaeme, the artist who runs the HomelessMuseum in New York. He proposed rebuilding theDirektorenhaus, giving it a ceremonial dedicationin 2026, having a plane bomb it into the groundin 2045 and then having the GDR house rebuilt in2056. Remember: The Direktorenhaus was builtin 1926, then destroyed in a bombing raid in 1945,and in 1956 a GDR house was built on the site,complete with gable roof. So Noterdaeme envisionedrepeating the act of destruction everyhundred years. I think that kind of dynamic historicizationis great—a sequence of reconstructionand redestruction. Re-enacting the courseof history as a loop would be more authentic andhonest than a simple reconstruction.Why do you think so much reconstruction is beingdone in Europe?The preservation of monuments is a European idea.In Asia they destroy a lot and can’t understandwhy we have so many old buildings and rebuild theones that have been destroyed. Africa is a wholesubject unto itself, and for a long time the USAhasn’t particularly pursued the idea either, althoughthere was a tendency there to rebuild European palacesas copies. But that phase is over now, becausethe Americans have their own identity and no longerregard themselves as ex-Europeans. The idea of acultural heritage that must be protected originatedin Europe. History is the only thing the Europeanshave left; they no longer have the status of a worldpower, and economically they’re not the strongesteither. That’s why it’s becoming more and moreimportant to cling tightly to the past.The interview is based on a public panel on December02, 2008 in Leipzig.Matthias Hollwich, Rainer Weisbach (Eds.): UmBauhaus – Aktualisierung der Moderne, Berlin 2004.Norbert Huse (Ed.): Denkmalpflege: Deutsche Texte aus drei Jahrhunderten, München 1996.Werner Schmidt: Der Hildesheimer Marktplatz seit 1945. Zwischen Expertenkultur und Bürgersinn,Hildesheim 1990.Walter Benjamin: Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit, Paris 1935/36.Giorgio Grassi: Hypothese einer Benutzung und architektonischen Wiederherstellung des römischenTheaters von Sagunto. Und: Apropos der Restaurierung von Sagunto. Both in: Michele Caja,Birgit Frank, Alexander Pellnitz, Jörg Schwarzburg (Eds.): Giorgio Grassi Ausgewählte Schriften1970–1999, Luzern 1986.Nikolaus Bernau: Die Berliner Museumsinsel, Bauwelt, issue 22, Berlin 1994240 / <strong>Reconstructions</strong> <strong>Displayer</strong>Guillaume Paoli / 241

0103 0405060201 Plan del teatro saguntino. Plan with exact particulars of the individual parts of theRoman theater.02 Detailed sketches of elements from the theater by J. Ortiz, 1807, Sagunto.03 Aerial view of the construction site at the beginning and near the end of the re-buildingof the Roman theater.04 Aerial view of the stage and the stands, Teatro de Sagunto, Giorgio Grassi,1986–1994, Sagunto.05 Depiction of Pulpitum, Parodoi, Orchestra and Cavea, Teatro de Sagunto, Giorgio Grassi,1986–1994, Sagunto.06 Detail of a original pillar with added parts, Praecinctiones in the background.242 / <strong>Reconstructions</strong> <strong>Displayer</strong>Giorgio Grassi / 243

08100908 Roofing ceremony of the Meisterhäuser in Dessau. The houses designed by Walter Gropius for the Bauhaus professors were finished in 1926.09 The house of the director in the year 1931. Six years later, it was completely destroyed.10 Gropius House, 2001: the house with the double pitch roof has been there for the last 40 years.244 / <strong>Reconstructions</strong> <strong>Displayer</strong>Guillaume Paoli / 245