Integrating technology in the classroom - Group Scribbles - National ...

Integrating technology in the classroom - Group Scribbles - National ...

Integrating technology in the classroom - Group Scribbles - National ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Orig<strong>in</strong>al articledoi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00323.x<strong>Integrat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>: a visualconceptualization of teachers’ knowledge, goalsand beliefsjcal_323 1..19F.-H. Chen, C.-K. Looi & W. Chen<strong>National</strong> Institute of Education, S<strong>in</strong>gaporeAbstractKeywordsIn this paper, we devise a diagrammatic conceptualization to describe and represent <strong>the</strong>complex <strong>in</strong>terplay of a teacher’s knowledge (K), goals (G) and beliefs (B) <strong>in</strong> leverag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>technology</strong>effectively <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. The degree of coherency between <strong>the</strong> KGB region and <strong>the</strong>affordances of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> serves as an <strong>in</strong>dicator of <strong>the</strong> teachers’ developmental progressionthrough <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation, implementation and maturation phases of us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.In our study, two teachers with differ<strong>in</strong>g knowledge, goals and beliefs are studied as <strong>the</strong>y<strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>Group</strong><strong>Scribbles</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>classroom</strong> lessons over a period of 1 year. Ourf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs reveal that <strong>the</strong> transition between <strong>the</strong> teacher’s developmental states (as <strong>in</strong>dicated bycoherency diagrams) is nonl<strong>in</strong>ear, and thus <strong>the</strong> importance of ensur<strong>in</strong>g high coherency right at<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation stage. Support for <strong>the</strong> teacher from o<strong>the</strong>r teachers and researchers rema<strong>in</strong>s animportant factor <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> teacher’s competency to leverage <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> successfully.The stability of <strong>the</strong> KGB region fur<strong>the</strong>r ensures smooth progression of <strong>the</strong> teacher’s effective<strong>in</strong>tegration of <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.teacher change, <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>, <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegration.IntroductionThere is much consensus that <strong>technology</strong> is now an<strong>in</strong>evitable and <strong>in</strong>tegral part of our everyday life, workand home experiences. Concomitantly, <strong>the</strong> call forschools to move to a more technologically <strong>in</strong>tegratedapproach to teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g has been resonat<strong>in</strong>gamong m<strong>in</strong>istries or departments of education <strong>in</strong>various countries. It is an undeniable fact that teachersplay a central role <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.In our previous paper (Chen & Looi 2008), wehave argued that <strong>the</strong> coherency between a teacher’sknowledge, goals and beliefs, i.e. ‘KGB’ and <strong>the</strong> affordancesof <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> is <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> key <strong>in</strong> leverag<strong>in</strong>gAccepted: 3 June 2009Correspondence: Fang-Hao Chen, <strong>National</strong> Institute of Education, 1Nanyang Walk, S<strong>in</strong>gapore 637616. Email: fanghao.chen@nie.edu.sg<strong>technology</strong> successfully <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. By view<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> teacher’s developmental trajectory through <strong>the</strong> threephases of <strong>in</strong>itiation, implementation and maturation, weexplore <strong>the</strong> different <strong>in</strong>terplay mechanisms between ateacher’s KGB and <strong>the</strong> affordances of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>.In this paper, we <strong>in</strong>vestigate <strong>the</strong> different knowledge,goals and beliefs of two teachers <strong>in</strong> a primary (elementary)school as <strong>the</strong>y <strong>in</strong>tegrate a <strong>technology</strong> called<strong>Group</strong><strong>Scribbles</strong> (GS) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir lessons that seeks toemploy collaborative and constructivist pedagogiesbased on <strong>the</strong> concepts of Rapid Collaborative KnowledgeBuild<strong>in</strong>g (DiGiano et al. 2006). In addition, wehave devised representations of ‘KGB diagrams’ andcoherency diagrams to better illustrate <strong>the</strong> complex<strong>in</strong>terplay of teacher’s knowledge, goals and beliefs <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>ir developmental trajectories as <strong>the</strong>y developed <strong>the</strong>ircompetencies <strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.At <strong>the</strong> end of this comparative study, we make some© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd Journal of Computer Assisted Learn<strong>in</strong>g 1

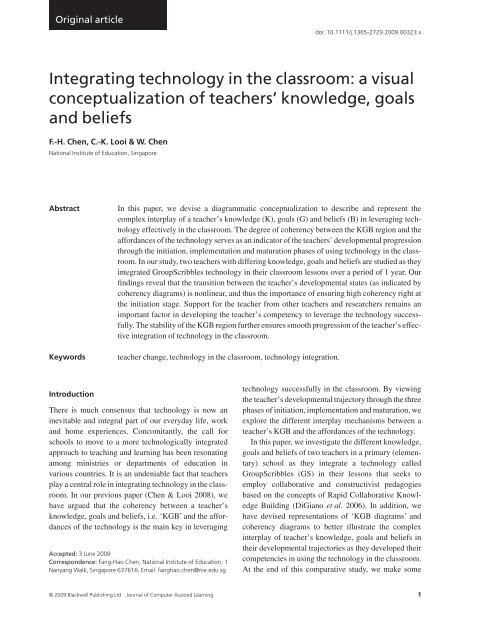

2 F.-H. Chen et al.notable assertions from our research and draw some recommendationsfor help<strong>in</strong>g teachers <strong>in</strong>tegrate <strong>technology</strong>more effectively <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.Literature reviewVarious research works have established that teachers’beliefs play an important role <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g teachers’<strong>in</strong>structional decisions and <strong>classroom</strong> practices (Cohen1990; Pajares 1992; Calderhead 1996; Ertmer 1999,2005). Aguirre and Speer (2000) argues that beliefs playa central role <strong>in</strong> a teacher’s selection and prioritizationof goals and actions <strong>in</strong> her teach<strong>in</strong>g. Moreover, beliefsshape how teachers perceive and <strong>in</strong>terpret <strong>classroom</strong><strong>in</strong>teraction which <strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>the</strong>ir responses anddecision-mak<strong>in</strong>g processes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.With <strong>the</strong> view that teacher’s beliefs have a profoundimpact on teach<strong>in</strong>g practices, a series of studies has beendone to <strong>in</strong>vestigate <strong>the</strong> relationships between a teacher’sbeliefs and <strong>technology</strong> use <strong>in</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. Ertmer (1999)describes two barriers to <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegration,namely, first-order barriers and second-order barriers.Second-order barriers are <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic to <strong>the</strong> teacher and<strong>the</strong>y <strong>in</strong>clude teachers’ beliefs which are harder to overcomethan first-order extr<strong>in</strong>sic barriers such as lack ofaccess to software, support and time. Therefore, <strong>the</strong>teacher’s beliefs have to be addressed adequately first <strong>in</strong>order to have mean<strong>in</strong>gful <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegration.Extend<strong>in</strong>g from this, Becker (2000) and Niederhauserand Stoddart (2001) <strong>in</strong>dicate that teachers who holdmore constructivists beliefs tend to use <strong>technology</strong> moreoften than those who held more teacher-centred beliefs.The research of Schoenfeld (1999, 2006) shows thatit is not only <strong>the</strong> teacher’s beliefs but <strong>the</strong> teacher’sknowledge and goals that play an important role <strong>in</strong>every pedagogical decision that <strong>the</strong> teacher makes. Indevelop<strong>in</strong>g a comprehensive model of <strong>the</strong> teacher’sdecision-mak<strong>in</strong>g process, Schoenfeld (1999) considers‘how goals, beliefs and knowledge serve to select andshape courses of action taken by <strong>the</strong> teacher.’The teacher’sknowledge, goals and beliefs <strong>in</strong>fluence each o<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong> a complex manner <strong>in</strong> every decision processembarked on by <strong>the</strong> teacher <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. This forms<strong>the</strong> underly<strong>in</strong>g architecture beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> TMG’s (TeacherModel <strong>Group</strong>) model. The basic idea is that a teacher’sdecision-mak<strong>in</strong>g and problem solv<strong>in</strong>g is a function of<strong>the</strong> teachers’ knowledge, goals and beliefs (Schoenfeld1999, 2006).Schoenfeld and <strong>the</strong> Teacher Model <strong>Group</strong> have utilized<strong>the</strong> TMG model <strong>in</strong> analys<strong>in</strong>g, expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and diagnos<strong>in</strong>gmany complex and widely vary<strong>in</strong>g teach<strong>in</strong>gepisodes (Arcavi & Schoenfeld 1992; Schoenfeld 1999;Schoenfeld et al. 2000) at multiple gra<strong>in</strong> sizes. Themodel has thus proven to be robust (Schoenfeld 2006).However, <strong>the</strong>re seems to be little work on <strong>the</strong> complex<strong>in</strong>terplay of <strong>the</strong> teacher’s knowledge, beliefs and goalsrelated to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegration of IT <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>TMG model. In this study, we seek to explore <strong>the</strong>seissues fur<strong>the</strong>r us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> KGB diagram and coherencydiagram mechanisms.Visual conceptualizationThe KGB diagramIn seek<strong>in</strong>g to represent <strong>the</strong> complex <strong>in</strong>terplay betweenteachers’ knowledge, goals and beliefs or ‘KGB’, wehave devised <strong>the</strong> ‘KGB diagram’ (Fig 1). In our study,<strong>the</strong> teacher’s beliefs (B) refer specifically to <strong>the</strong> epistemologicalbeliefs of <strong>the</strong> teachers. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong>sebeliefs concern teachers’ views about <strong>the</strong> nature ofknowledge and how knowledge is learned (Hofer & P<strong>in</strong>trich1997). These conceptions of knowledge impact <strong>the</strong>teach<strong>in</strong>g practices of a teacher (Brownlee et al. 2002).Goals (G) are what a teacher sets to accomplish <strong>in</strong> class(Schoenfeld 1999). These goals can be <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic to <strong>the</strong>teacher and coherent with her beliefs, or <strong>the</strong>y can beextr<strong>in</strong>sic to <strong>the</strong> teacher and imposed upon her by <strong>the</strong>school, community, or o<strong>the</strong>r stakeholders. The knowledgeof a teacher (K) <strong>in</strong>cludes content knowledge, pedagogicalcontent knowledge and knowledge of <strong>the</strong>students (Bransford et al. 2000).KGB regionFig 1 KGB diagram.1Teacher’sknowledge(K)5Teacher’sbeliefs (B)6 723Teacher’sgoals (G)84© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

<strong>Integrat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> 3In <strong>the</strong> Mentored and Onl<strong>in</strong>e Development of EducationalLeaders <strong>in</strong> Science program that supportsteachers’ professional development to implement<strong>technology</strong>-enhanced <strong>in</strong>quiry <strong>in</strong>struction, <strong>the</strong>se knowledgecomponents (content knowledge, pedagogicalcontent knowledge and knowledge of students’ learn<strong>in</strong>g)have been identified as core areas of teachers’knowledge enhancement (Lee & Spitulnik 2008). The<strong>the</strong>oretical framework of design<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se professionaldevelopment activities is founded on <strong>the</strong> KnowledgeIntegration (KI) framework (L<strong>in</strong>n 2000, 2006; Slotta &L<strong>in</strong>n 2000). Some activities <strong>in</strong>clude connect<strong>in</strong>g teachers’exist<strong>in</strong>g knowledge about teach<strong>in</strong>g with new waysof teach<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>technology</strong> (Davis 2004) and scaffold<strong>in</strong>gteachers to make <strong>the</strong>ir own th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g visible via <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>gwith <strong>the</strong>ir peers through a forum (Lee &Spitulnik 2008).The ‘KGB diagram’ represents teacher beliefs (B),goals (G) and knowledge (K) as separate circular setrepresentations. Each region <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> KGB diagram iscontextualized with respect to a specific situation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>classroom</strong> where a teacher’s K, G and B are brought tobear <strong>in</strong> her teach<strong>in</strong>g, shap<strong>in</strong>g her <strong>in</strong>tentions, <strong>in</strong>teractionsand o<strong>the</strong>r decisions she has to make. In Fig 1, we havedivided <strong>the</strong> KGB diagram <strong>in</strong>to eight regions for clarityof explanation. Regions 1, 2 and 3 denote <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersectionof two circular sets, regions 4, 5, and 6 denote no<strong>in</strong>tersection while region 7 denotes <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection ofall three circular sets.Region 1 represents <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection between teacher’sknowledge and teacher’s beliefs. It denotes a <strong>classroom</strong>situation where <strong>the</strong> teacher applies selectedknowledge that is coherent with <strong>the</strong> beliefs of <strong>the</strong>teacher but may not be relevant <strong>in</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>g any goals <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. This is particularly true if <strong>the</strong> goals areextr<strong>in</strong>sic to <strong>the</strong> teacher. For example, aligned with a particularbelief about collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>g, a teachermay implement portfolio assessment strategies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>class. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Gearhart and Herman (1998), portfoliosconta<strong>in</strong> products of <strong>classroom</strong> <strong>in</strong>struction <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g‘an engaged community <strong>in</strong> a supportive learn<strong>in</strong>gprocess’that is suitable for collaborative group learn<strong>in</strong>g.Research done by Webb (1993, 1995) suggests that an<strong>in</strong>dividual’s performance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of group activitymay or may not represent his or her capability. In herf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, low ability students had higher scores on agroup work than on <strong>in</strong>dividual work because effortswere assisted. Therefore, if <strong>the</strong> goal set for <strong>the</strong> class by<strong>the</strong> school is to do well for high stakes <strong>in</strong>dividual traditionalassessments, students that did well <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> portfolioassessment may or may not achieve <strong>the</strong>ir desiredgrades for <strong>the</strong> traditional assessments.An overlapp<strong>in</strong>g of K and G but not B results <strong>in</strong> region2. In this scenario, <strong>the</strong> teacher’s goals <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>are set by external <strong>in</strong>fluences such as <strong>the</strong> school, whichmay run contradictory to <strong>the</strong> teacher’s beliefs. Never<strong>the</strong>less,<strong>the</strong> teacher possesses <strong>the</strong> knowledge necessaryto achieve <strong>the</strong> goals. For example, a teacher mightstrongly believe <strong>in</strong> collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>but under certa<strong>in</strong> constra<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> school curriculum,a teacher might revert to didactic methods or rotelearn<strong>in</strong>g to teach a particular lesson. A consideration ofB and G toge<strong>the</strong>r produces region 3. In this situation, <strong>the</strong>teacher may have multiple goals for <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> butshe has to weigh her goals accord<strong>in</strong>g to her beliefs. Forexample, a teacher may have <strong>the</strong> dual goals of build<strong>in</strong>gan impressive portfolio for herself and hav<strong>in</strong>g her studentslearn. However, when <strong>the</strong> goals conflict <strong>in</strong> anyparticular situation, <strong>the</strong> teacher will prioritize <strong>the</strong> goalsbased on her beliefs and this will impact <strong>the</strong> decisionmak<strong>in</strong>gprocess <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.Regions 4, 5 and 6 denote <strong>classroom</strong> situations <strong>in</strong>which <strong>the</strong> teacher’s goals, beliefs and knowledge aremutually dist<strong>in</strong>ct without each hav<strong>in</strong>g any <strong>in</strong>fluence oneach o<strong>the</strong>r. Usually, <strong>the</strong>se perta<strong>in</strong> to latent knowledge,goals and beliefs that were not relevant to <strong>the</strong> currentteach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g situation of <strong>the</strong> teacher. However,<strong>the</strong>se circular sets are not static but dynamic. Anychanges to <strong>the</strong> external environment will trigger ei<strong>the</strong>r ashift <strong>in</strong> or a resiz<strong>in</strong>g of any circular sets, to cause anydormant goals, beliefs and knowledge to <strong>in</strong>tersect withone ano<strong>the</strong>r. Region 8 lies outside of <strong>the</strong> KGB set. Thisregion represents <strong>the</strong> external <strong>in</strong>fluences and socialforces that can act on <strong>the</strong> teacher, <strong>the</strong>reby <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> KGB diagram. The susceptibility to <strong>the</strong>se changes isstrongly subjected to <strong>the</strong> stability of <strong>the</strong> teacher’s KGB.Usually, a teacher with long teach<strong>in</strong>g experiences has afar more stable KGB, as compared with a noviceteacher. Thus, <strong>the</strong>ir susceptibility to changes is far lessand <strong>the</strong>ir KGB diagram will rema<strong>in</strong> relatively static ascompared with a novice teacher whose KGB diagram isrelatively more dynamic, with cont<strong>in</strong>ual shift<strong>in</strong>g andresiz<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> circular sets.The central region 7 represents <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection of <strong>the</strong>teacher’s knowledge, beliefs and goals, <strong>the</strong> KGBregion. This region denotes <strong>the</strong> teacher’s selection of© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

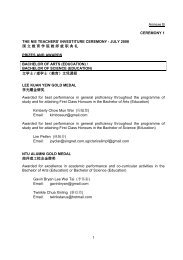

4 F.-H. Chen et al.knowledge, that based on goals, are prioritized by his orher beliefs. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, this region expla<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> typeof teacher’s decisions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> that are alignedwith <strong>the</strong> teacher’s goals, beliefs and knowledge. In thisview, good teach<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>technology</strong> requires an alignmentof <strong>the</strong> all three elements: K, G and B. In leverag<strong>in</strong>gany <strong>technology</strong> effectively <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> teacher mustpossess knowledge of <strong>the</strong> affordances of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>and how to use <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> to achieve goals that areset for <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.Affordances refers to both <strong>the</strong> perceivedand actual fundamental properties of <strong>technology</strong>that determ<strong>in</strong>e just how <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> could possiblybe used (Norman 1990) and <strong>the</strong>y are objectively measurableand <strong>in</strong>dependent of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual’s ability torecognize <strong>the</strong>m (Gibson 1977). Clearly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> KGBregion, <strong>the</strong> goals and knowledge of <strong>the</strong> teacher areshaped and <strong>in</strong>fluenced by <strong>the</strong> teacher’s beliefs. Hence,<strong>the</strong> teacher’s beliefs, <strong>in</strong> this case, provide <strong>the</strong> affectivemotivation for teacher to utilize <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>.The coherency diagramTechnology is treated as a knowledge system that isbiased (Hickerman 1990) and possesses its own propensities,biases and <strong>in</strong>herent attributes (Bruce 1993;Bromley 1998). Some <strong>technology</strong> is more suitable forcerta<strong>in</strong> tasks than o<strong>the</strong>rs. Thus, <strong>technology</strong> cannot betreated as a knowledge base unrelated from knowledgeabout teach<strong>in</strong>g tasks and contexts – it is not only aboutwhat <strong>technology</strong> can do, but also, and perhaps moreimportantly, what <strong>technology</strong> can do for teachers(Koehler et al. 2007). Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, for <strong>technology</strong> tobecome an <strong>in</strong>tegral component or tool for learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>subject, teachers must also develop ‘an overarch<strong>in</strong>gconception of <strong>the</strong>ir subject matter with respect to <strong>technology</strong>and what it means to teach with <strong>technology</strong>pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK)’ (Niess 2005).Angeli and Valanides (2009) argues that <strong>in</strong> leverag<strong>in</strong>g<strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g, it is important to consider teacher’sbeliefs, <strong>in</strong> addition to knowledge (content, <strong>technology</strong>and pedagogy). A disregard of teacher’s beliefs isconsidered as ‘naïve perceptions about <strong>the</strong> nature of<strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g.’(Angeli & Valanides 2009, p. 157). Hence, we need toconsider <strong>the</strong> teacher’s knowledge, goals and beliefs <strong>in</strong>relation to <strong>the</strong> affordances of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> orderto study <strong>the</strong> harness<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g. Tocapture this relation, we <strong>in</strong>troduce <strong>the</strong> coherencyThe <strong>in</strong>tersection region denotes <strong>the</strong>extent of <strong>technology</strong> that is exploitedKGB regionFig 2 Coherency diagram.Affordancesof<strong>technology</strong>diagram (Fig 2) as a representation to describe <strong>the</strong>extent to which <strong>technology</strong> is leveraged <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>relation to <strong>the</strong> teacher’s KGB region.In Fig 2, <strong>the</strong> size of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection region determ<strong>in</strong>es<strong>the</strong> extent of coherency between KGB region and <strong>the</strong>affordances of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong>greater <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection, <strong>the</strong> more effectively <strong>the</strong> affordancesof <strong>technology</strong> will be leveraged by <strong>the</strong> teacher <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. The effective usage of any <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> must align with <strong>the</strong> knowledge, goals andbeliefs of <strong>the</strong> teacher. As <strong>the</strong> teacher develops cognitiveand affective competencies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> use of a <strong>technology</strong>,<strong>the</strong> KGB region will gradually be shifted more to <strong>the</strong>right, caus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection area to <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> size.On <strong>the</strong> contrary, <strong>the</strong> teacher may also develop negativeviews about <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> or misconceptions about <strong>the</strong>affordances of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> that may affect <strong>the</strong> KGBregion, caus<strong>in</strong>g it to shift to <strong>the</strong> left, <strong>the</strong>reby reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>tersection area.The coherency diagram is dynamic and exists <strong>in</strong>tandem with <strong>the</strong> teacher’s developmental trajectory <strong>in</strong>us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. If we map out <strong>the</strong>entire repertoire of <strong>in</strong>tersection regions, one wouldrealize that <strong>the</strong>y lie <strong>in</strong> a cont<strong>in</strong>uum. Hence, <strong>the</strong> coherencydiagram serves as an <strong>in</strong>dicator of teacher’s developmentalstate <strong>in</strong> <strong>technology</strong> competency.Four states <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uum of coherencyAlthough <strong>the</strong> coherency diagram views <strong>the</strong> developmentalstages <strong>in</strong> a cont<strong>in</strong>uum, it is useful to divide <strong>the</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>uum <strong>in</strong>to four dist<strong>in</strong>ct states shown <strong>in</strong> Fig 3.These states encompass all possible <strong>classroom</strong> scenarioswhere <strong>technology</strong> is implemented. State 1denotes pictorially that <strong>the</strong> affordances of <strong>the</strong> technol-© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

<strong>Integrat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> 5(cont<strong>in</strong>uum of coherency diagram)(<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tersection between KGB region and affordances of <strong>technology</strong>)|-----------------------------------|----------------------------|------------------------------------------------|State 1 State 2 State 3 State 4State 1: NocoherencyState 2: LittlecoherencyState 3: MuchcoherencyState 4: TotalcoherencyFig 3 Four states along <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uum <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> coherency diagram. White circle represents‘KGB region’. Grey circle represents‘Technology affordances’.There is no<strong>in</strong>tersection.Technology is notleveraged at all.There is little<strong>in</strong>tersection.Technology isleveraged to a limitedextent.There is much<strong>in</strong>tersection.Technology isleveraged at a largeextent.There is total<strong>in</strong>tersection. Hence,total coherency.Many affordances of<strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> areleveraged. This forms<strong>the</strong> ideal state.ogy are not leveraged by <strong>the</strong> teacher at all. This stateforms one end of <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uum. As <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> state 2, <strong>technology</strong> is deployed to a limitedextent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. Cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g along <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uum,state 3 denotes a situation where much coherencyis depicted. In this case, <strong>technology</strong> is leveraged toa large extent. State 4 denotes <strong>the</strong> upper limit of <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uum.It is a state where all affordances of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>are leveraged, and <strong>the</strong>re is total coherency between<strong>the</strong> KGB region of <strong>the</strong> teacher and <strong>the</strong> affordances of <strong>the</strong><strong>technology</strong>. This state forms <strong>the</strong> ideal state. The variousstates are not time dependent and a teacher could beg<strong>in</strong>,progress, regress, or end at any state. They attempt notonly to describe a teacher’s KGB region and its relationto <strong>the</strong> leverag<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>’s affordances at anyone po<strong>in</strong>t, but also to serve as important <strong>in</strong>dicators of herdevelopment progress from one state to ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g<strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. The transition from onestate to ano<strong>the</strong>r is qualitatively and quantitativelyassessed <strong>in</strong> terms of <strong>the</strong> leverag<strong>in</strong>g of affordances of <strong>the</strong><strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.Research contextOur focus <strong>in</strong> this study is <strong>the</strong> analysis of <strong>the</strong> teacher’spersonal experiences <strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>classroom</strong>. We adopt a case study approach <strong>in</strong> mapp<strong>in</strong>gout each teacher’s developmental trajectories us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>Coherency diagram. This model provides a systematicframework for us to ga<strong>the</strong>r relevant data as to teachers’knowledge, goals and beliefs about <strong>the</strong> GS <strong>technology</strong>at each developmental milestone, and to do comparativestudies between different implementation paths takenby each teacher.Research and <strong>in</strong>tervention contextIn our research project, we have collaborated with twoteachers, namely, Lynn and May. These teachers wereselected based on <strong>the</strong>ir different KGB characteristics sothat a contrast<strong>in</strong>g comparison can be done at <strong>the</strong> end ofour study. Lynn is an experienced primary schoolteacher <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> latter stages of her successful career <strong>in</strong>teach<strong>in</strong>g. In contrast with o<strong>the</strong>r teachers <strong>in</strong> her school,Lynn (before our study) was a <strong>technology</strong> novice, us<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> computer ma<strong>in</strong>ly for record<strong>in</strong>g grades, email communicationsand word process<strong>in</strong>g. Despite this, she volunteeredto participate <strong>in</strong> this project and was will<strong>in</strong>g tomove up <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g curve.May is a young female teacher with about 5 years ofteach<strong>in</strong>g experience. She puts <strong>in</strong> effort <strong>in</strong> her <strong>classroom</strong>management, cares for her students and does not neglect<strong>the</strong> weaker students. She is under pressure to producehigh-grade students as <strong>the</strong> school faces pressure toproduce not just good students, but star students, so as toattract more parents to send <strong>the</strong>ir children to school.May is relatively more IT-savvy than Lynn.In S<strong>in</strong>gapore, <strong>the</strong> school year starts <strong>in</strong> January andends <strong>in</strong> November. We started our study <strong>in</strong> July 2007work<strong>in</strong>g with Lynn and May <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir primary school <strong>in</strong>S<strong>in</strong>gapore. Lynn and May teach different classes <strong>in</strong>grade 4. We started with 6 weeks of Paper <strong>Scribbles</strong>,which are activities us<strong>in</strong>g sticky paper notes, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>classroom</strong>s as an <strong>in</strong>itiation phase. This is a means to© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

6 F.-H. Chen et al.Ma<strong>the</strong>maticslessonsMa<strong>the</strong>matics topicsSciencelessonsScience topicsTable 1. Topics that are taught <strong>in</strong> Lynn’sand May’s ma<strong>the</strong>matics and scienceclasses.Week 1 Equivalent fractions Week 1 GenesWeek 2 Area of a triangle Week 2 Parts of a flowerWeek 3 Division of fractions Week 3 Plant poll<strong>in</strong>ationWeek 4 Ratio of two quantities Week 4 Seed dispersalWeek 5 Ratio of three quantities Week 5 Plant reproductionWeek 6 Stem cutt<strong>in</strong>gWeek 7 Experiment plann<strong>in</strong>gWeek 8 Transfer of energybeg<strong>in</strong> enculturat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> teachers and <strong>the</strong> students <strong>in</strong>to<strong>the</strong> practice of rapid collaborative bra<strong>in</strong>storm<strong>in</strong>g andcritiqu<strong>in</strong>g, and to develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> relevant protocols andsocial etiquettes. Easy-to-use sticky notes are adoptedto facilitate <strong>the</strong> students’ use <strong>in</strong> contribut<strong>in</strong>g ideas to anactivity posed by <strong>the</strong> teacher and <strong>in</strong> comment<strong>in</strong>g oneach o<strong>the</strong>rs’ post<strong>in</strong>gs.Subsequently, <strong>the</strong> class switched to <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> GS<strong>technology</strong> for 10 weeks. The students and teacherswere provided tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for two sessions of an hour each.They <strong>the</strong>n used GS for science lessons for ano<strong>the</strong>r 10weeks. Each week, <strong>the</strong>y had a 1 h GS science lesson <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> computer laboratory. These GS lessons formed ourprimary core data for analysis. In our <strong>in</strong>structionaldesign, we tried to <strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g ten pr<strong>in</strong>ciples,of which <strong>the</strong> latter five were adapted fromScardamalia (2002):• distributed cognition – design<strong>in</strong>g for th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g to bedistributed across people, tools and artefacts,• volunteerism – lett<strong>in</strong>g learners choose what piece of<strong>the</strong> activity <strong>the</strong>y want to participate <strong>in</strong>,• spontaneous participation – design<strong>in</strong>g for quick, lightweight<strong>in</strong>teraction driven by students <strong>the</strong>mselves,• multimodal expression – accommodat<strong>in</strong>g differentmodes of expression for different students,• higher-order th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g – encourag<strong>in</strong>g analysis, syn<strong>the</strong>sis,evaluation, sort<strong>in</strong>g, or categoriz<strong>in</strong>g,• improvable ideas – provid<strong>in</strong>g a conducive environmentwhere ideas can be critiqued and madebetter,• idea diversity – explor<strong>in</strong>g ideas and related/contrast<strong>in</strong>g ideas, encourag<strong>in</strong>g different ideas,• epistemic agency – encourag<strong>in</strong>g students to takeresponsibility for <strong>the</strong>ir own and one ano<strong>the</strong>r’slearn<strong>in</strong>g,• democratized knowledge – everybody participatesand is a legitimate contributor to knowledge,• symmetric knowledge advancement – expertise isdistributed, and advanced via mutual exchanges.In January 2008, we cont<strong>in</strong>ue our <strong>in</strong>volvement with<strong>the</strong> teachers; <strong>the</strong> students are now <strong>in</strong> grade 5. Everyweek for 10 weeks, two lesson periods (totall<strong>in</strong>g an hourand 10 m<strong>in</strong>) for <strong>the</strong> subjects of science and ma<strong>the</strong>maticsadopt GS lessons which are conducted <strong>in</strong> a computerlab. In <strong>the</strong>se two classes of 40 students, each student hasan <strong>in</strong>dividual Tablet-PC (TPC) with a GS client software<strong>in</strong>stalled. In total, we have co-designed, implementedand observed five ma<strong>the</strong>matics lessons andeight science lessons as shown <strong>in</strong> Table 1.GS as a <strong>technology</strong> that supports rapid collaborativeknowledge build<strong>in</strong>gThe motivation for our <strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> school stemsfrom <strong>the</strong> realization that <strong>the</strong>re is an ever-<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g needto provide students with learn<strong>in</strong>g experiences thatreflect <strong>the</strong> unique challenges and opportunities of <strong>the</strong>21st century. One key class of skills relates to rapid collaborativeknowledge build<strong>in</strong>g which <strong>in</strong>clude problemidentification, bra<strong>in</strong>storm<strong>in</strong>g, prioritiz<strong>in</strong>g, conceptmapp<strong>in</strong>g and action plann<strong>in</strong>g (DiGiano et al. 2006). Byharness<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se techniques <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>, it is possiblefor students both to learn exist<strong>in</strong>g subject mattermore deeply and also to become participants <strong>in</strong> 21stcentury knowledge build<strong>in</strong>g practices. These techniquescan be enacted with a lightweight <strong>technology</strong>such as GS, which enables collaborative generation,collection and aggregation of ideas through a sharedspace based upon <strong>in</strong>dividual effort and social shar<strong>in</strong>g ofnotes <strong>in</strong> graphical and textual form.© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

<strong>Integrat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> 7Fig 4 A Morae screenshot of <strong>the</strong> publicor group board (upper pane) and privateboard (lower pane).Table 2. GS features that support flexible collaborative work.FeaturesRepresentationallyneutralInformalLightweightMeta<strong>in</strong>formatic(Re)arrangableUniqueShareableAnonymous identityDescriptionsGS can capture diagrams and draw<strong>in</strong>gs as well as text. Different sizes afford different k<strong>in</strong>ds ofactivities.GS uses relatively small size of virtual post<strong>in</strong>g pads (scribbles sheet: 3 ¥ 5 <strong>in</strong>ch and label sheet:3 ¥ 3 <strong>in</strong>ch) suited for quick sketches or notes ra<strong>the</strong>r than highly f<strong>in</strong>ished ideas.The scribble sheets are for concise ideas <strong>in</strong>stead of lengthy explanations.The scribble sheets can annotate o<strong>the</strong>r representations, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g o<strong>the</strong>r post<strong>in</strong>g sheets.The scribble sheets can be positioned and repositioned to convey mean<strong>in</strong>g.As a virtual artefact, each scribble sheet cannot be <strong>in</strong> more than one place at a time,suggest<strong>in</strong>g turn-tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> edit<strong>in</strong>g or chang<strong>in</strong>g.The scribble sheet can be easily passed from one person to any group workspace. The samesheet can be retracted from <strong>the</strong> group workspace for ref<strong>in</strong>ement or elaboration.GS has <strong>the</strong> feature of veil<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> user’s identity. However, access to <strong>the</strong> identity of <strong>the</strong> authorof each scribble sheet can be made available to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>structor.Adapted from DiGiano et al. 2006.GS, <strong>Group</strong><strong>Scribbles</strong>.The GS user <strong>in</strong>terface presents each user with a twopanedw<strong>in</strong>dow. The lower pane is <strong>the</strong> user’s personalwork area, or ‘private board’, with a virtual pad of fresh‘scribble sheets’on which <strong>the</strong> user can draw or type (seeFig 4). The essential feature of <strong>the</strong> GS client is <strong>the</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ationof <strong>the</strong> private board where students can work<strong>in</strong>dividually and group boards or public boards wherestudents can view o<strong>the</strong>rs’ work, post <strong>the</strong>ir work andposition it relative to o<strong>the</strong>rs’ work, and take items backto <strong>the</strong> private board for fur<strong>the</strong>r elaboration.Figure 4 shows a lesson activity <strong>in</strong> class <strong>in</strong> which eachstudent posts answers to <strong>the</strong> question ‘When does <strong>the</strong>heart beat faster/slower?’ <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private board, and <strong>the</strong>nmoves <strong>the</strong>ir answers to <strong>the</strong> public board for shar<strong>in</strong>g. Thestudents’ scribble notes showed a multiplicity of ideas<strong>the</strong>y generated which enabled <strong>the</strong> teacher to <strong>in</strong>itiate discussionson <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g post<strong>in</strong>gs.Table 2 depicts <strong>the</strong> basic features of GS that are suggestiveof <strong>the</strong> affordances of GS for support<strong>in</strong>g studentparticipation <strong>in</strong> designed collaborative activities. In collaborative<strong>classroom</strong>s, groups of learners and <strong>the</strong>irteachers take on roles, contribute ideas, critique eacho<strong>the</strong>r’s work, and toge<strong>the</strong>r solve aspects of larger problems(Hake 1998).© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

8 F.-H. Chen et al.Data collectionIn our collection of data, two or more researchersobserve each class and make detailed field observationnotes. One video camera is set beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> torecord <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> session, while two o<strong>the</strong>r videocameras are focused on two target groups of students.Screen captur<strong>in</strong>g software Morae 2.0 is <strong>in</strong>stalled on<strong>the</strong> TPCs to record <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>teraction of <strong>the</strong> students us<strong>in</strong>gGS. We approach our data analysis from different perspectives<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g uptake analysis (Looi et al. 2008), aswell as analysis of surveys, <strong>in</strong>terviews and performancetests (Ng et al. 2008). We have also employed semistructured<strong>in</strong>terviews as a method to ga<strong>in</strong> access to <strong>the</strong>subjective understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> teacher. This <strong>in</strong>cludes anhour-long <strong>in</strong>terview conducted at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> semesterand weekly post-lesson conference sessions. In <strong>the</strong> postlessonconference sessions, <strong>the</strong> teacher is prompted toreflect on <strong>the</strong> lesson and articulate her own analysis of<strong>the</strong> lesson. This proves to be a useful source of data forus, as it reveals many subtle beliefs that <strong>the</strong> teacher hold.In <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> semester, <strong>the</strong> teacher is <strong>in</strong>terviewed bytwo researchers with a list of prepared <strong>in</strong>terview questions<strong>in</strong> a private location. The <strong>in</strong>terview sessions arerecorded by audio and video. In <strong>the</strong> work reported <strong>in</strong> thispaper, our multifaceted data collection and analysis issituated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> frame of qualitative analysis and <strong>the</strong> casestudy formalisms of Stake (2000).AnalysisThis section discusses <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> coherency diagrams<strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g May’s and Lynn’s various pivotaldecisions to <strong>in</strong>tegrate <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> curriculum.This is done by establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir beliefs, goals andknowledge <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first <strong>in</strong>stance and <strong>the</strong>n employ<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong>m as lenses to expla<strong>in</strong> and understand <strong>the</strong> variousGS-related activities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>.Phases of <strong>technology</strong> implementation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>In our previous paper (Chen & Looi 2008), <strong>the</strong> differentimplementation phases of <strong>technology</strong>, namely <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiationphase, <strong>the</strong> implementation phase and <strong>the</strong> maturationphase are discussed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of Lynn’sdevelopmental trajectory. Each phase denotes a generaltime-based developmental milestone for <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g<strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. However, <strong>the</strong> timeIncrease <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>tersectionregionDecrease <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>tersectionregionFig 5 Units of developmental trajectories. White circle represents‘KGB region’. Grey circle represents ‘Technology affordances’.required to progress from each phase to ano<strong>the</strong>r variesfrom teacher to teacher. Every teacher has a differenttrajectory with different <strong>in</strong>itiation, implementation andmaturation phases, and <strong>the</strong>se can be described withcoherency diagrams.The <strong>in</strong>itiation phase denotes <strong>the</strong> teacher’s <strong>in</strong>itialexposure to <strong>technology</strong>. The teacher must be conv<strong>in</strong>cedboth affectively and cognitively to accept <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. In order for a teacher’s KGBregion to be coherent with <strong>the</strong> affordances of <strong>technology</strong>,i.e. state 3 of Fig 3, <strong>the</strong> perceived affordances of <strong>the</strong><strong>technology</strong> must align with <strong>the</strong> teacher’s KGB. Morealignment will imply more <strong>in</strong>tersection. Therefore,some practical recommendations at this phase <strong>in</strong>cludeopportunities for <strong>the</strong> teacher to articulate her KGBdur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itial exposure to <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> and align <strong>the</strong>affordances of <strong>technology</strong> to her KGB. In <strong>the</strong> implementationphase, <strong>the</strong> teacher proceeds to use <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. If <strong>the</strong> perceived coherency <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation phase is enacted successfully <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> real<strong>classroom</strong>, <strong>the</strong>re will be an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> her confidence <strong>in</strong>us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>. Diagrammatically, this would be<strong>in</strong>dicated by an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection between <strong>the</strong>KGB region and <strong>the</strong> affordances of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>. If<strong>the</strong> converse occurs, it may signal a decrease <strong>in</strong> confidenceand motivation to use <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>. This is <strong>in</strong>dicated<strong>the</strong>n, by a decrease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection region,caus<strong>in</strong>g a regression. These units of developmental trajectoriesare shown <strong>in</strong> Fig 5. Therefore, affirm<strong>in</strong>g teacher’sconfidence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first few lessons is very important<strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g confidence and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g motivation.Lastly, <strong>the</strong> maturation phase denotes a phase where<strong>the</strong> teacher garners enough positive experience to use<strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> despite technical glitches of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>.This is <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al phase if <strong>the</strong> teacher has persisted <strong>in</strong>us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>. Ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dicator is that <strong>the</strong>teacher may have found <strong>in</strong>novative ways <strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><strong>technology</strong>. Usually, this phase is characterized by state© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

<strong>Integrat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> 93 or 4 of Fig 3 because it denotes certa<strong>in</strong> technical competenceand confidence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> teacher. Note that <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>itiation and implementation phases, <strong>the</strong> teacher’scoherency diagram can occur at any po<strong>in</strong>t along <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uumof <strong>the</strong> coherency diagrams, i.e. states 1 to 4.However, <strong>the</strong>re is a possibility that a teacher may notachieve <strong>the</strong> maturation phase at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>implementation period, especially if <strong>the</strong> teacher’sdevelopmental trajectory is regress<strong>in</strong>g along <strong>the</strong> coherencydiagram cont<strong>in</strong>uum <strong>in</strong>stead of progress<strong>in</strong>g.Lynn’s developmental trajectoryLynn’s KGB is reported <strong>in</strong> our previous paper (Chen &Looi 2008). In this section, we illustrate Lynn’s developmentaltrajectory via <strong>the</strong> coherency diagrams, support<strong>in</strong>gour analysis by describ<strong>in</strong>g some empiricalobservations. This is summarized <strong>in</strong> Table 3.Initiation phaseIn <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation phase, Lynn beg<strong>in</strong>s her developmentalpath at state 3. There is much alignment between herKGB and her perceptions of <strong>the</strong> affordance of <strong>the</strong> GS<strong>technology</strong>. First, she believes that as a teacher, patiencewith <strong>the</strong> students is very important to help studentslearn. She expresses this belief <strong>in</strong> her own words:‘patience with <strong>the</strong> students is very important to make achild (student) learn. Rais<strong>in</strong>g your voice aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong>mwill make th<strong>in</strong>gs worse.’ This belief is fundamental too<strong>the</strong>r beliefs that she holds. She firmly believes thataddress<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> emotional needs of students is central tostudents’ learn<strong>in</strong>g, that <strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g a good rapport with<strong>the</strong> students, ‘<strong>the</strong> children need to know that teacherunderstands and cares about <strong>the</strong>m,’ and that it is importantto assure students that it is alright ‘not to know’.Therefore, she believes that students <strong>in</strong> her class shouldbe comfortable enough to admit that <strong>the</strong>y have made amistake and that w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> hearts of <strong>the</strong> studentsis important <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g. Second, shebelieves that ‘not every student is <strong>the</strong> same’and that <strong>the</strong>ypossess diverse abilities. She also resolves not to let anystudents <strong>in</strong> her class feel ‘<strong>in</strong>ferior’. Students <strong>in</strong> her classhave different strengths and because of <strong>the</strong>se beliefs,she has put <strong>in</strong> place a collaborative culture that is suitablefor <strong>the</strong> students to learn from each o<strong>the</strong>r. Lastly, shealso believes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> importance of teach<strong>in</strong>g ‘th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gskills <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>’. This belief motivates her toadopt pedagogies that teach cognitive skills such aspost<strong>in</strong>g good comments and design<strong>in</strong>g questions forpeer teach<strong>in</strong>g.Concern<strong>in</strong>g beliefs about <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>classroom</strong>, Lynn expresses her views succ<strong>in</strong>ctly: ‘it isimportant to keep up with <strong>the</strong> times. Nobody forces meto use GS <strong>in</strong> my <strong>classroom</strong>. I believe that one must bepositive <strong>in</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g, especially <strong>in</strong> IT’. When askedfur<strong>the</strong>r, Lynn reflects that this positive m<strong>in</strong>dset is pivotalfor her <strong>in</strong> overcom<strong>in</strong>g obstacles <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g GS <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>classroom</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation stage and <strong>in</strong> exploit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>affordances of GS to <strong>the</strong> fullest. This <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic motivationto learn has led her to be open to changes and hasresulted <strong>in</strong> good work<strong>in</strong>g relationship with <strong>the</strong> researchstaff.Closely l<strong>in</strong>ked to her beliefs are her ‘overarch<strong>in</strong>g’goals (Schoenfeld 1999) <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g GS <strong>technology</strong><strong>in</strong> her <strong>classroom</strong>. In <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terview with Lynn, sheexpresses that her ma<strong>in</strong> goal is ‘to see her children (students)learn because this gives a lot of satisfaction’ toher. In a conversation with her Head of Department, headds that Lynn took up GS <strong>technology</strong> because ‘it is anopportunity for her to build up her portfolio as a seniorteacher as she is compet<strong>in</strong>g with ano<strong>the</strong>r seniorteacher’. We tend to <strong>in</strong>fer that Lynn may hold two overarch<strong>in</strong>ggoals, but her beliefs about teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>gmay have helped her to prioritize <strong>the</strong> goal of ‘see<strong>in</strong>gher children (students) learn’ as a more important goal.Her beliefs have also provided a focus for Lynn to selectknowledge appropriate for effective learn<strong>in</strong>g. Becauseof her long teach<strong>in</strong>g career, Lynn possesses reasonablygood content and pedagogical content knowledge of herteach<strong>in</strong>g subjects – ma<strong>the</strong>matics and science. This isconfirmed <strong>in</strong> separate <strong>in</strong>terviews with some of her students.One student notes that she is a ‘knowledgeableteacher who is correct most of <strong>the</strong> time’. They alsocomment that <strong>the</strong>y ‘enjoyed her lessons and were able tounderstand what she was teach<strong>in</strong>g’.Because of her strong belief that every child is able tolearn, Lynn has devised lessons that are relevant to <strong>the</strong>students and are able to leverage <strong>the</strong> affordances of GSto her advantage. Lynn perceived <strong>the</strong>se affordances tobe congruent with her student-centred beliefs and goals.The affordances of GS <strong>technology</strong> complement andenhance her knowledge of content, pedagogy, and herclass. For example, <strong>the</strong> features of GS <strong>technology</strong> allowher to teach science lessons better <strong>in</strong> a collaborativesett<strong>in</strong>g. In addition, although she is a <strong>technology</strong> novice,© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

10 F.-H. Chen et al.Table 3. Lynn’s developmental trajectory.Phases Lynn’s knowledge (K) Lynn’s beliefs (B) Lynn’s goals (G) Affordances of <strong>technology</strong> Coherency diagramInitiationphaseImplementationphaseMaturationphaseLynn’s knowledge aboutcollaborative learn<strong>in</strong>gstrategies and <strong>the</strong>different abilities amongher students.Lynn’s knowledge aboutdifferent learn<strong>in</strong>g stylesprofiles <strong>in</strong> her students.Lynn’s knowledge aboutcollaborative learn<strong>in</strong>gstrategies and <strong>the</strong>different abilities amongher students.Lynn’s knowledge aboutdifferent learn<strong>in</strong>g stylesprofiles <strong>in</strong> her students.Lynn’s <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>knowledge, e.g. work<strong>in</strong>gwith researchers, PD andtra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programmes.1 Lynn’s beliefs about <strong>the</strong> valuesof <strong>the</strong> different abilities <strong>in</strong> herstudents and <strong>the</strong> importance ofpeer learn<strong>in</strong>g.2 She believes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> importanceof be<strong>in</strong>g patient with herstudent <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g affirm<strong>in</strong>g andprais<strong>in</strong>g her students isimportant <strong>in</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g.Lynn’s beliefs about <strong>the</strong> values of<strong>the</strong> different abilities <strong>in</strong> herstudents.1 Lynn’s beliefs about <strong>the</strong> valuesof <strong>the</strong> different abilities <strong>in</strong> herstudents and <strong>the</strong> importance ofpeer learn<strong>in</strong>g.2 Also, she believes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>importance of be<strong>in</strong>g patientwith her student <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gaffirm<strong>in</strong>g and prais<strong>in</strong>g herstudents is important <strong>in</strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g.Lynn’s beliefs about <strong>the</strong> values of<strong>the</strong> different abilities <strong>in</strong> herstudents.Lynn’s goal is to create agood collaborativelearn<strong>in</strong>g environment.Lynn’s goal is to givestudents freedom toexpress <strong>the</strong>ir solutions <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>ir desired form.Lynn’s goal is to create agood collaborativelearn<strong>in</strong>g environment.Lynn’s goal is to givestudents freedom toexpress <strong>the</strong>ir solutions <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>ir desired form.Lynn’s positive learn<strong>in</strong>g attitudes. Lynn is determ<strong>in</strong>ed to learnas much as possible sothat she can be an<strong>in</strong>dependent competentGS <strong>technology</strong> user.Lynn perceives that <strong>the</strong>shared spaces <strong>in</strong> GSprovided a goodplatform to post, buildand improve each o<strong>the</strong>r’sideas to allow studentsto learn from oneano<strong>the</strong>r.Lynn perceives that <strong>the</strong>multimodal affordancesof GS are aligned withher KGB.Lynn successfully utilizes<strong>the</strong> shared space <strong>in</strong> GSfor collaborativelearn<strong>in</strong>g.Lynn successfullyimplementedmultimodal expressions<strong>in</strong> her GS class lessons.Lynn is able to handletechnical glitches bydevis<strong>in</strong>g ‘filler’ activitiesas well as m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>gglitches.Because <strong>the</strong>re is muchalignment with <strong>the</strong>Lynn’s KGB and <strong>the</strong>perceived <strong>technology</strong>,Lynn starts off withstate 3.There are successes <strong>in</strong>implement<strong>in</strong>g what Lynnperceived. Hence, <strong>the</strong>reis <strong>in</strong>creased confidence <strong>in</strong>us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> GS <strong>technology</strong>.This would be <strong>in</strong> state 3.Lynn is able to handletechnical glitches.Therefore, she is close tostate 4.White circle represents ‘KGB region’; Grey circle represents ‘Technology affordances’.GS, <strong>Group</strong><strong>Scribbles</strong>; PD, professional development.© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

<strong>Integrat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> 11Fig 6 Multimodal expressions <strong>in</strong> a <strong>Group</strong>-<strong>Scribbles</strong> science lesson.<strong>the</strong> user-friendl<strong>in</strong>ess features of GS gives her <strong>the</strong> confidencethat she is able to learn it well later.Implementation phaseIn <strong>the</strong> implementation phase, Lynn implements whatshe perceived as coherent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation phase <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>classroom</strong>. In our case study, Lynn is able to leverage<strong>the</strong> multimodal and shared space affordances of <strong>the</strong> GS<strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> her lessons.Multimodal expressions <strong>in</strong> GS. In many of Lynn’sscience lessons (weeks 1–5, 8; see Table 1), ‘live’specimensare used for students to sense and observe. Forexample, she br<strong>in</strong>gs plant seeds for lesson 4 and flowersfor lessons 2 and 3. By allow<strong>in</strong>g students to observe andsense <strong>the</strong> specimens, she caters to <strong>the</strong> different learn<strong>in</strong>gstyles (visual, tactile, k<strong>in</strong>es<strong>the</strong>tic and audio) of <strong>the</strong> students<strong>in</strong> her class. This stems from her belief that everystudent learns differently, as mentioned <strong>in</strong> section 4.1.This belief also causes her to leverage on <strong>the</strong> affordanceof GS which allows students to express <strong>the</strong>ir answers on<strong>the</strong> pad <strong>in</strong> different forms such as draw<strong>in</strong>g or typ<strong>in</strong>g, i.e.<strong>the</strong> ‘representationally neutral’ feature of GS as shown<strong>in</strong> Table 2. This has produced a rich variety of answers,as shown <strong>in</strong> Figs 6 and 7. In Fig 6, some students preferto draw and colour while o<strong>the</strong>r students prefer to type.Some students prefer not to post anyth<strong>in</strong>g but verbalize<strong>the</strong>ir answers dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lesson. Similarly <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>the</strong>maticslessons, different students articulate <strong>the</strong>iranswers <strong>in</strong> different modes as shown <strong>in</strong> Fig 7. Lynn’sbelief <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> diverse abilities and learn<strong>in</strong>g styles amongher students motivates her to plan and implementlessons that cater to different learn<strong>in</strong>g styles of her students.In this way, <strong>the</strong> multimodal affordances of GS areleveraged upon.Shared space <strong>in</strong> GS as a platform for collaborativelearn<strong>in</strong>g. Lynn’s student-centred beliefs enable her tocreate a conducive environment that promotes collaborativelearn<strong>in</strong>g. In her lessons, students are allowed toexpress <strong>the</strong>ir answers without fear of criticism. This isnot only seen <strong>in</strong> verbal articulation but also <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>written ideas on GS boards. Below is a transcript thathappened <strong>in</strong> her science lesson on transfer of energy:Lynn: What is <strong>the</strong> answer to <strong>the</strong> question? Anybodyknow?Student 1: Eagle?Lynn: Not really. However, that was a good attempt.Anybody else want to try?(students <strong>in</strong> her class beg<strong>in</strong> to see that <strong>the</strong> student whoprovides an <strong>in</strong>appropriate answer will not be reprimanded,more students raises <strong>the</strong>ir hands)Student 2: Caterpillar.Lynn: Very good answer. Whole class give student 2 aclap. (whole class gives a clap)Lynn: Alright, everybody please write your answers on<strong>the</strong> GS groupboard.© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

12 F.-H. Chen et al.Fig 7 Multimodal expressions <strong>in</strong> a<strong>Group</strong><strong>Scribbles</strong> ma<strong>the</strong>matics lesson.Lynn encourages her students to give constructivecomments so that <strong>the</strong>ir self-esteem might be boosted.She gives praise as much as possible and <strong>in</strong> her lessons,very few <strong>in</strong>cidences of chid<strong>in</strong>g are observed. Below isano<strong>the</strong>r transcript <strong>in</strong> her science lesson on seeddispersal.Lynn: Tell me how? <strong>the</strong> seeds can be dispersed? And giveme some examples of it.Student 1: By w<strong>in</strong>d. Pollen gra<strong>in</strong>s.Lynn: Very good! O<strong>the</strong>r answers?Student 2: By water.Lynn: Any examples?Student 2: ur. . . .Lynn: Anybody can help student 2? I th<strong>in</strong>k student 2 hasgiven a good answer but any examples? (Lynn did notscold student 2 for be<strong>in</strong>g unable to give <strong>the</strong> example)Student 3: Coconut.Lynn: Excellent!In addition, her belief <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> diverse abilities amongher students causes her to value every view that her studentsarticulated. She implements group collaborativelearn<strong>in</strong>g because she believes it is a good avenue for studentsto build upon each o<strong>the</strong>rs’ knowledge. Shebelieves that collaboration maximizes learn<strong>in</strong>g, andthus is more will<strong>in</strong>g to exploit <strong>the</strong> features of GS <strong>technology</strong>that support collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>g shown <strong>in</strong>Table 2, e.g. view<strong>in</strong>g o<strong>the</strong>r group boards, peer review<strong>in</strong>geach o<strong>the</strong>r’s ideas, and post<strong>in</strong>g ideas <strong>in</strong> real time asshown <strong>in</strong> Figs 6 and 7. These affordances are leveragedsuccessfully <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>g.Because of <strong>the</strong>se reasons, we could observe substantialcollaborative results, e.g. evidences of peer learn<strong>in</strong>g andcritique, higher order th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g skills, richer content,etc., because of <strong>the</strong> collaborative culture that she hasbuilt <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> class (Looi et al. 2008).Maturation phaseAfter a period of implementation, she has reached closeto state 4 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> maturation phase. In this phase, she hasdevised her own ways to cope with <strong>the</strong> limitations of <strong>the</strong>GS <strong>technology</strong>, such as devis<strong>in</strong>g suitable filler activitieswhen <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong> fails, complement<strong>in</strong>g GS <strong>technology</strong>with W<strong>in</strong>dows Journal, and plann<strong>in</strong>g GS-relatedlessons under <strong>the</strong> constra<strong>in</strong>ts of <strong>the</strong> GS-<strong>technology</strong> (e.g.not load<strong>in</strong>g large background pictures that will ‘hang’<strong>the</strong> GS <strong>technology</strong>). Hence, as we trace <strong>the</strong> coherencydiagrams, Lynn exhibits a positive upward growth fromstate 3 to state 4 <strong>in</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>technology</strong> successfully<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. The transition from state 3 tostate 4 is a smooth and relatively easy one for Lynn.Lynn enjoys <strong>the</strong> GS <strong>technology</strong> so much that she commentsthat she will ‘use GS <strong>in</strong> her <strong>classroom</strong> even when<strong>the</strong> researchers are not around’.May’s developmental trajectoryInitiation phaseAt <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention, May holds severalprimary beliefs about teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g. First, she© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd

<strong>Integrat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>technology</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> 13believes that enabl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> students to do well <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>exam<strong>in</strong>ations is <strong>the</strong> primary task of <strong>the</strong> teacher. Sheexpresses this belief <strong>in</strong> her own words, ‘I wanted mystudents to achieve academically. That is <strong>the</strong> mostimportant’. Follow<strong>in</strong>g closely to this primary belief, herlessons have orientations towards prepar<strong>in</strong>g students toperform on exam<strong>in</strong>ations. She expects herself to f<strong>in</strong>ish<strong>the</strong> syllabus on time adher<strong>in</strong>g to a strict schedule calledscheme of work (SOW). Second, she believes that herstudents are ‘generally weak and unable to articulate<strong>the</strong>ir answers well enough’ and generally believes tha<strong>the</strong>r students ‘need to be guided and are not used to <strong>in</strong>dependentlearn<strong>in</strong>g’. This has caused her to employ didacticteach<strong>in</strong>g strategies <strong>in</strong> her lessons, e.g. pos<strong>in</strong>g veryclose-ended questions and enact<strong>in</strong>g IRE (Initiation-Response-Evaluation) episodes frequently <strong>in</strong> herlessons. Below shows a transcript <strong>in</strong> one of her sciencelesson on parts of a plant:May: Which part of <strong>the</strong> plant will form <strong>the</strong> fruit?(Initiation-close ended question)Student 1: Stigma (Response)May: Stigma? That is not really <strong>the</strong> part (Evaluationcloseended)Student 2: Style (Response)Teacher: Style? Wrong. Sorry (Evaluation)Third, she believes that strict <strong>classroom</strong> management isrequired to achieve optimal task behaviour <strong>in</strong> students.She cannot tolerate any excessive noise <strong>in</strong> her <strong>classroom</strong>and believes that discipl<strong>in</strong>e and orderl<strong>in</strong>ess is <strong>the</strong> wayfor students to learn effectively. She expects her studentsto follow her <strong>in</strong>structions <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ute detail. Therefore,her goals <strong>in</strong>clude complet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> SOW on time andexpect<strong>in</strong>g a quiet, discipl<strong>in</strong>ed and orderly class for everylesson.Hence, May’s KGB region entails apply<strong>in</strong>g herknowledge of didactic strategies to ensure completionof <strong>the</strong> syllabus and preserv<strong>in</strong>g a discipl<strong>in</strong>ed class forevery lesson, based on her beliefs that her studentsshould be taught to be ‘exam-oriented’ and that <strong>the</strong>y aregenerally unable to articulate <strong>the</strong>ir answers wellenough. Therefore, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation phase, May perceivesmany of <strong>the</strong> affordances of GS <strong>technology</strong> to bemisaligned to her KGB region. The affordances of GS<strong>technology</strong> is primarily leveraged for collaborativelearn<strong>in</strong>g which requires students to articulate <strong>the</strong>ir ideasand to work toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> groups to solve open-endedquestions posed by <strong>the</strong> teacher. In addition, collaborativelearn<strong>in</strong>g demands more time, which will cause Maynot to complete her syllabus on time. Moreover, Mayfaces difficulty <strong>in</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>gactivities for GS-related lessons because of her limitedknowledge concern<strong>in</strong>g teach<strong>in</strong>g methods. Lastly, Lynnonce commented that May was ‘persuaded to jo<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>research collaboration <strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g GS <strong>technology</strong>’ withou<strong>the</strong>r consent be<strong>in</strong>g sought first. All <strong>the</strong>se factors po<strong>in</strong>ts to<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>coherency between May’s KGB region and <strong>the</strong>affordances of GS <strong>technology</strong>, and this can be aptly<strong>in</strong>dicated by state 1 as shown <strong>in</strong> Fig 1.Implementation phase (part 1)As May enacts <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>coherencies perceived <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiationphase, she is not able to leverage <strong>the</strong> <strong>technology</strong>effectively <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong>. First, her fear of not be<strong>in</strong>gable to complete her lessons on time has materialized <strong>in</strong>some of her GS lessons as she could not complete her<strong>in</strong>tended lesson objectives. This is partly because of herpoor time management skills <strong>in</strong> a group collaborativelesson. From our <strong>classroom</strong> observations, we note thatMay constantly seeks to enforce strict discipl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> herGS group collaboration lessons. This causes a lot oftension <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> as students tend to talk andarticulate more dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se lessons while May tries toma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> order <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>classroom</strong> by giv<strong>in</strong>g numerous<strong>in</strong>structions and expects her students to comply. Here isan episode of May’s strict <strong>classroom</strong> management <strong>in</strong> ascience lesson:May: Have I f<strong>in</strong>ished my <strong>in</strong>struction?Class: No.May (repeated aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> agitated tone): Have I f<strong>in</strong>ished my<strong>in</strong>struction?Class: No.May: Then why are you people start<strong>in</strong>g to do your workalready?May (turned to student A): A, what did you do <strong>in</strong> X’spost?May: What was my <strong>in</strong>struction? If you draw on yourboard, how are you go<strong>in</strong>g to drag it on your groupboard?May (shout<strong>in</strong>g): Everyone 2 f<strong>in</strong>gers up! 2 FINGERS UP!May wastes much lesson time <strong>in</strong> try<strong>in</strong>g to enforce discipl<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> GS lessons and she reckons that more timeis needed for collaborative group work. She succ<strong>in</strong>ctlyexpresses this frustration: ‘GS is time consum<strong>in</strong>g anddra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. It has prevented me somehow from cover<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> syllabus.’ Second, technical glitches that have unexpectedlycropped up <strong>in</strong> her first few lessons have fur<strong>the</strong>rreduced her confidence and motivation to use GS <strong>technology</strong><strong>in</strong> her lessons. In fact, she has attributed <strong>the</strong> poor© 2009 Blackwell Publish<strong>in</strong>g Ltd