SUMMARY - Safe Medications Management project: Key issues and ...

SUMMARY - Safe Medications Management project: Key issues and ...

SUMMARY - Safe Medications Management project: Key issues and ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

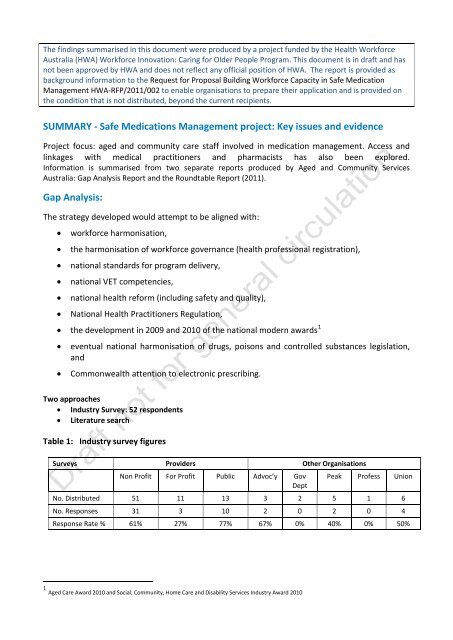

The findings summarised in this document were produced by a <strong>project</strong> funded by the Health WorkforceAustralia (HWA) Workforce Innovation: Caring for Older People Program. This document is in draft <strong>and</strong> hasnot been approved by HWA <strong>and</strong> does not reflect any official position of HWA. The report is provided asbackground information to the Request for Proposal Building Workforce Capacity in <strong>Safe</strong> Medication<strong>Management</strong> HWA-RFP/2011/002 to enable organisations to prepare their application <strong>and</strong> is provided onthe condition that is not distributed, beyond the current recipients.<strong>SUMMARY</strong> - <strong>Safe</strong> <strong>Medications</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>project</strong>: <strong>Key</strong> <strong>issues</strong> <strong>and</strong> evidenceProject focus: aged <strong>and</strong> community care staff involved in medication management. Access <strong>and</strong>linkages with medical practitioners <strong>and</strong> pharmacists has also been explored.Information is summarised from two separate reports produced by Aged <strong>and</strong> Community ServicesAustralia: Gap Analysis Report <strong>and</strong> the Roundtable Report (2011).Gap Analysis:The strategy developed would attempt to be aligned with:workforce harmonisation,the harmonisation of workforce governance (health professional registration),national st<strong>and</strong>ards for program delivery,national VET competencies,national health reform (including safety <strong>and</strong> quality),National Health Practitioners Regulation, the development in 2009 <strong>and</strong> 2010 of the national modern awards 1eventual national harmonisation of drugs, poisons <strong>and</strong> controlled substances legislation,<strong>and</strong>Commonwealth attention to electronic prescribing.Two approaches Industry Survey: 52 respondents Literature searchTable 1: Industry survey figuresSurveys Providers Other OrganisationsNon Profit For Profit Public Advoc’y GovDeptPeak Profess UnionNo. Distributed 51 11 13 3 2 5 1 6No. Responses 31 3 10 2 0 2 0 4Response Rate % 61% 27% 77% 67% 0% 40% 0% 50%1 Aged Care Award 2010 <strong>and</strong> Social, Community, Home Care <strong>and</strong> Disability Services Industry Award 2010

1. Results of Industry SurveyThe Consultants identified emerging themes under the key domains.1.1. Issues Identified By DomainsIn presenting the results, the Professional/Industry Codes <strong>and</strong> Guidelines Themes have beencombined with the Legislative/Regulatory Themes as respondents frequently did not discriminatebetween these two Domains in their responses.1.1.1. Workforce ThemesRecruitment difficulties RNs & ENs - Residential & CommunityUnpopular field of nursing – high workloads, little recognition, not as prestigious.High proportion of older RNs approaching retirement.Pay disparities with acute hospital nursing.Shortage of RNs <strong>and</strong> ENs in rural <strong>and</strong> remote areas.High turnover.Few full time nurses – placing high dem<strong>and</strong>s on those who are full time or work substantialhours.Low staffing levels - ResidentialFunding formulae does not match resident/client needs or unexpected absences <strong>and</strong>unfilled shifts (see Recruitment above).Many ENs do not want the responsibility of medication administration.Workloads – Residential Onerous <strong>and</strong> time-consuming regulatory, transaction <strong>and</strong> compliance dem<strong>and</strong>s -Residential Aged Care St<strong>and</strong>ards, documentation, authorisations, checking prepackedmedicines from Pharmacy, “chasing” scripts from doctors & supplies from pharmacies.Insufficient time to supervise, teach <strong>and</strong> mentor care staff. Increasing numbers ofresidents in both low <strong>and</strong> high care settings require specialised nursing <strong>and</strong>/or complexcare, resulting in a need for more supervision of personal care staff.High requirement for RNs to undertake all or most of the medication administration. Thiscan be time consuming due to complex care, polypharmacy & medication managementarrangements required to address resident swallowing problems, combined with broadermanagement roles.1.1.2. Clinical Practice ThemesKnowledge, skills, competency, <strong>and</strong> literacy of care staff:Inconsistencies in training personal care staff on medication management.2

Inconsistencies in achieving <strong>and</strong> maintaining competency levels especially in medicationmanagement.Issues of English literacy <strong>and</strong> comprehension of staff from non English speakingbackgrounds.No systems or requirements for continuing education <strong>and</strong> training of personal care staff.Little time or funding for RN <strong>and</strong> ENs to attend to continuing professional development(CPD) requirements in work time.Scope of Practice, Professional Guidelines, <strong>and</strong> organisational policies <strong>and</strong> procedures:Inconsistencies in Scope of Practice between States/Territories for RNs <strong>and</strong> ENs <strong>and</strong> nomeans for staff to be trained to meet new Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency(AHPRA) Scope of Practices (SoPs) where relevant.Poor knowledge <strong>and</strong> compliance with Scope of Practice, policies <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ards/guidelinespossibly because of,o workload <strong>and</strong> time constraints,o management knowledge <strong>and</strong> skills,o absence of relevant training for staff in these matters, <strong>and</strong>/oro inability to recruit suitable staff.Pharmacy difficulties:Frequent packing errors in Dose Administration Aids (DAA) <strong>and</strong> other dispensed medicines.Delays in receiving medication supplies.Changes to DAA packing <strong>and</strong>/or presentations without notice.Changes to medication br<strong>and</strong>s supplied without notice or discussion. This is oftendisturbing for residents/clients <strong>and</strong> their families, particularly if different in appearance.Delays in getting emergency medicines – usually for pain.GP or Local Medical Officer (LMO) difficulties:Inconsistencies in notating cessation date of drugs on Medication Charts.Delays in writing up new scripts for new/changed medications, phone orders or for newMedication Charts in timely fashion.Delays in addressing urgent pain needs of residents <strong>and</strong> especially community clients.1.1.3. Legislative/Regulatory, <strong>and</strong> Professional/Industry Codes <strong>and</strong> Guidelines ThemesInterstate Regulatory/Guidelines inconsistenciesDifferent provisions regarding dispensing, possession <strong>and</strong> administration of medications ineach State/Territory.3

Inconsistent regulations relating to storage <strong>and</strong> checking of medications – some due toDrugs <strong>and</strong> Poisons Regulations, <strong>and</strong> some due to State/Territory Health Authoritym<strong>and</strong>atory policy. Different regulations <strong>and</strong> policies on medication dispensing, possession, administration <strong>and</strong>checking for hospitals, community <strong>and</strong> aged care facilities.Professional, Health Authority <strong>and</strong> Industry St<strong>and</strong>ards, Guidelines <strong>and</strong> PositionsMultiplicity of Registration Board, Professional, Health Authority <strong>and</strong> Industry Codes <strong>and</strong>Guidelines on Medication <strong>Management</strong> – some of which have no “authority” sinceState/Territory Registration Boards ceased to exist with the commencement of AHPRA.Poor underst<strong>and</strong>ing by all staff (nursing <strong>and</strong> carers) as to what is regulated, what is “goodpractice” <strong>and</strong>/or local policy/practice regarding medication administration <strong>and</strong>management.Different Accreditation St<strong>and</strong>ards on Medication <strong>Management</strong> – ACQSHC, ACHS, ACSAA.Personal Care Workers,o Inconsistent scope of practice across states.(Lack of consistent training, education <strong>and</strong> meaningful inclusion in national <strong>and</strong> stateworkforce planning for aged residential <strong>and</strong> community care, despite making up thebulk of the workforce.)Table 2: Distribution of Themes from 323 Major Issues Identified <strong>and</strong> Coded.Workforce Clinical Practice Regulations & GuidelinesStaffinglevelsSkills,training etcRecruitmentWorkloadsNoncompliance & errorsPharmacyGPsInconsistenciesMultipli-cityUnreg’dworkers39 24 66 44 30 26 36 23 19 1312% 7% 20% 14% 9% 8% 11% 7% 6% 4%1.2. Barriers in medication processes to effective <strong>and</strong> efficient medication managementRespondents were asked to rank 7 elements of the medication process listed below, from 1 to 7,with 1 being the most problematic. 2 Reported in Table 5 are the “No 1” problems identified by 39of the 52 respondents.2 The question was not included in the survey sent to non-provider organisations <strong>and</strong> not alleligible respondents completed the question.4

Table 3: List of BarriersBarrier ItemN reported as No 1 barrierMedication orders/chart 15Administration 12Prescribing 8Dispensing <strong>and</strong> labelling 3Supply <strong>and</strong> receipt 1Storage 0Disposal 01.3. Packaging <strong>and</strong> Charting IssuesA majority of respondents commented specifically on packaging <strong>and</strong> charting revealing thefollowing results:Packaging:8 (23.5%) used mainly pre-packaged medicines, using bottles/boxes only for respite clientsor in unusual circumstances, <strong>and</strong> 26 (76.5%) used only pre-packaged medicines.Charting:4 (9%) used both paper <strong>and</strong> electronic charts,24 (73%) used paper charts only, <strong>and</strong>5 (15%) used electronic charts only.1.4. Suggested ImprovementsRespondents were asked to nominate 3 key improvements which would enable their organisationto provide more efficient <strong>and</strong> effective medication management for its clients. Analysis of theresponses highlighted some common themes. There were also a large number of practicalsuggestions on medication practices which could be implemented by an organisation as part of itsown quality improvement system. Since these are not dependent on national strategies, systemsor regulation for implementation at a local level they have not been included here.5

Table 4: <strong>Key</strong> Themes for ImprovementsThemeNumber of citationsElectronic medication & communication systems 25Increased/consistent education on medication managementguidelines <strong>and</strong>/or legal matters for RNs, ENs, GPs <strong>and</strong>unlicensed health workers (UHNs)Workforce improvements including staff increases <strong>and</strong> betterpay <strong>and</strong> conditionsNationally consistent sets of guidance <strong>and</strong>/or regulation onmedication management <strong>and</strong> those who deliver its variouselementsImproved communication <strong>and</strong> support between Aged CareFacilities/GPs/Pharmacies <strong>and</strong> Acute HospitalsReduced “overmedication” <strong>and</strong> “polypharmacy” 7St<strong>and</strong>ardised Medication Chart/Charts as Scripts 6St<strong>and</strong>ardised <strong>and</strong> limited range of Drug Administration Aids 5212018151.4.1. Electronic medication & communication systemsRespondents’ suggestions on electronic systems for use in residential <strong>and</strong> community aged care,ranged from electronic charts, to electronic prescribing, ordering, charting <strong>and</strong> recording systems,with or without integration with GP practices <strong>and</strong> pharmacies. It is likely that these suggestedimprovements reflect a wide range of experience <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing of electronic systemsamongst those completing the surveys.1.4.2. Increased/consistent education on medication management guidelines <strong>and</strong>/orlegal matters for GPs, RNs, ENs, <strong>and</strong> personal care workersThese suggestions included:Increased education <strong>and</strong> training, including agreed minimum qualifications in medicationmanagement for personal care workers,Overall increases in education, training <strong>and</strong> competency testing for RNs <strong>and</strong> ENs inmedication management generally,Managing certain medication types (e.g. insulin, anticoagulants), <strong>and</strong> in non-chemicalbehavioural <strong>and</strong> pain management for all categories of care personnel (nurses, doctors,pharmacists <strong>and</strong> other allied health professionals, <strong>and</strong> personal care workers),Education <strong>and</strong> updating for all categories of care personnel in the legal <strong>and</strong> policy/guidelineframeworks governing medication management practice.6

It was apparent that some respondents themselves had little underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the differencesbetween Statute <strong>and</strong> Common Law, particularly in relation to consent.1.4.3. Workforce improvements including staff increases <strong>and</strong> better pay <strong>and</strong> conditionsThe most frequently suggested workforce improvement cited not only by RNs, ENs & personalcare workers, but also GPs, Pharmacists, <strong>and</strong> administrative/clerical staff, was to increase staffinglevels. There were also suggestions of improving the staff mix between nurses <strong>and</strong> personal careworkers, which were not quantified.Other suggestions included increased pay (sometimes noting the need for parity with public sectoror acute hospital rates), improved conditions <strong>and</strong> inducements/ incentives to attract students <strong>and</strong>qualified staff into Aged Care.1.4.4. Nationally consistent sets of guidance <strong>and</strong>/or regulation on medicationmanagement <strong>and</strong> those who deliver its various elementsSuggested improvements included the st<strong>and</strong>ardisation of laws <strong>and</strong> guidelines. It was evident thatmany respondents were unclear about which, if any, laws or regulations governed aspects ofpractice. In addition there was a presumption by many that some departmental policies, <strong>and</strong> stateor national st<strong>and</strong>ards, codes <strong>and</strong> guidelines had the force of law. Some respondents clearly sawsimple, clear <strong>and</strong> nationally consistent guidance or law as a major plank in any platform toimprove the safety, effectiveness <strong>and</strong> efficiency of medication management in the settings inwhich they worked.1.4.5. Improved communication <strong>and</strong> support between Aged CareFacilities/GPs/Pharmacies <strong>and</strong> Acute HospitalsA range of suggestions were made by respondents for improvements to communication systemsbetween these stakeholders, but many were non-specific as to what strategies should be adoptedto enable the improvements sought. Several suggested use of a single rather than multiplepharmacies as well as increasing the levels of:pharmacy back-up/support, consultation about medication changes with both pharmacies <strong>and</strong> GPs, <strong>and</strong>/or ,consultation with staff by prescribing GPs <strong>and</strong> use of Residential Medication <strong>Management</strong>Reviews.There were also some suggestions of employing an “in house” pharmacist <strong>and</strong>/or GP. Some notedthat prescribing needed to be more aligned with:the practicalities of either residents’ overall health status <strong>and</strong> limitations; <strong>and</strong>/or,community organisations’ resource limitations in administering or providing assistancewith medications more than once or twice a day.Most of the system-based specific suggestions have been covered under the education/training orelectronic systems themes above.A few respondents drew attention to the need to have mechanisms in place in acute hospitals toensure that when medications which were current on someones admission are changed, that this7

is communicated clearly <strong>and</strong> in a timely fashion with the relevant residential care/community careagencies, GPs <strong>and</strong> pharmacies. This open communication would ensure all parties had thenecessary information to manage the transition from acute to residential setting or own home.1.4.6. Reduced “overmedication” <strong>and</strong> “polypharmacy”Most respondents who suggested these improvements were non-specific as to the method ofachieving them other than improved education <strong>and</strong> training, particularly in palliative care <strong>and</strong>behaviour management. Polypharmacy was identified specifically as a key clinical practice problemby a number of respondents.1.4.7. St<strong>and</strong>ard Medication Chart/Charts as ScriptsSome jurisdictions or organisations use the medication chart as the prescription, or supply thechart to the pharmacy which then “chases” the GP for the actual prescription. This is identified asan improvement to practice <strong>issues</strong>. Electronic systems were also seen as an improvement whichwould facilitate smoother <strong>and</strong> timely renewal <strong>and</strong> cessation of orders in line with best medicationpractice.1.4.8. St<strong>and</strong>ardised <strong>and</strong> limited range of Drug Administration AidsRespondents referred to having to deal, not only with a range of Dose Administration Aids (DAA),but with them being changed either by the manufacturer or other parties involved in themedication management processes for any given resident, community or client.1.5. Other improvements/considerations from the Survey FindingsThere were a h<strong>and</strong>ful of respondents who raised some interesting <strong>and</strong> possibly highly important<strong>issues</strong>. They have not been identified elsewhere as they were mostly “one-offs” rather thanmatters shared with several other respondents.However three very important matters emerged:Exploration of medication management in people’s homes where a number of people(client, carer, service providers, GPs <strong>and</strong> Pharmacists) are all participants in prescribing,supplying, storing, administering, monitoring <strong>and</strong> disposing of medicines.Complementary medicines <strong>and</strong> interventions in residential care. In many cases, the facilityor the treating GP may be reluctant to consider such treatment, or prohibit it altogether. Itis a complex area, but to maintain optimum independence <strong>and</strong> choice for residents, it mustbe considered in terms of ethics, safety, legality, right <strong>and</strong> risks.English language proficiency of staff (particularly care workers) <strong>and</strong> visiting professionals inresidential care facilities. This included strategies which would mitigate the risks ofmisunderst<strong>and</strong>ings <strong>and</strong> errors. A resource in this area is the International Medication<strong>Safe</strong>ty Network which offers a range of practical tools to address these <strong>issues</strong>. Otheravenues, such as English proficiency requirements (similar to Police Checks processes) <strong>and</strong>education options could also be considered.8

2. Literature review of key documents2.1. Legislative FrameworkThe National Competition Policy Review of Drugs, Poisons <strong>and</strong> Controlled Substances LegislationReport (The Report) was presented to the Australian Health Ministers Conference (AHMC) inJanuary 2001 with 27 recommendations. The Chair of the Review, Rhonda Galbally, wrote in thecovering letter to the Report that,“Despite differences in demographics across the States <strong>and</strong> Territories, Australia is increasinglybecoming a single market <strong>and</strong> national uniformity is a recurring issue. In this report, Irecommend the development <strong>and</strong> adoption by reference of model medicines <strong>and</strong> poisonslegislation in order to achieve uniformity. I accept that this may not be supported by alljurisdictions; however, I think that one of the purposes of the Review is to set some benchmarkstowards a nationally uniform system of regulation. I hope that you will give seriousconsideration to the adoption of model legislation, <strong>and</strong> alternatively, I challenge you to worktowards national uniformity following another path.” 3The Report recognised the importance of the close relationship between drugs <strong>and</strong> poisonslegislation <strong>and</strong> legislation regulating professional practice. It confirmed that comprehensivelegislation to regulate drugs <strong>and</strong> poisons was still required. Recommendation No. 24 specificallyrecommended that uniform national model legislation be developed <strong>and</strong> adopted.Whilst all States <strong>and</strong> Territories supported the concept of uniformity, the Report noted thatcurrent drugs <strong>and</strong> poisons legislation is complimented by other legislation <strong>and</strong> may not bepossible. Some states <strong>and</strong> territories (QLD, NT, WA) proposed alternative strategies to achieve thesame outcome.The Report also urged professional registration boards to consider options for improvingeffectiveness of their legislation to achieve compliance. Recommendation No. 27 specified that insome cases it might be appropriate for professional practice legislation to deem certain breachesof drugs <strong>and</strong> poisons legislation as professional misconduct. This matter is now under thejurisdiction of the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency, (AHPRA). The Working Part ofAHMC accepted the recommendations <strong>and</strong> undertook further consultation, but was unsuccessfulin gaining uniformity of legislation Other means to achieve uniformity are being investigated - thestatus of this work is not known.Appendix A provides a list of all relevant legislation on Medicare, drugs, poisons <strong>and</strong> health.2.1.1. Australian Government LegislationThe three major pieces of national legislation which provide a framework for medicationmanagement <strong>and</strong> older people are: The National Health Act 1953, The Aged Care Act 1997; <strong>and</strong> The Therapeutic Goods Act 1989.3 National Competition Policy Review of Drugs, Poisons <strong>and</strong> Controlled Substances LegislationReport 20009

In addition, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme has an important role both in the community <strong>and</strong>in residential care through the provision of medicines via PBS scripts.A comparison of the legislation follows:2.1.1.1. The National Health Act 1953This Act relates to the provision of pharmaceutical, sickness <strong>and</strong> hospital benefits, <strong>and</strong> of medical<strong>and</strong> dental services <strong>and</strong> is administered by the Australian Government Department of Health <strong>and</strong>Ageing.Relevant definitions in this legislation relate to – (authorised) <strong>and</strong> (eligible) nurse practitioner <strong>and</strong>(approved) pharmacist defined <strong>and</strong> referred to in Part I <strong>and</strong> Part VII of the Act. A medicalpractitioner <strong>and</strong> an authorised nurse practitioner are also defined as PBS prescribers. It does referto a medical practitioner being authorised to write a prescription for the supply of apharmaceutical. The only specific reference to aged care is where a prescribed institution means aresidential care service within the meaning of the Aged Care Act 1997.There are no other references to aged care, medicines or health professionals’ roles <strong>and</strong>responsibilities.2.1.1.2. The Aged Care Act 1977The Aged Care Act 1997, <strong>and</strong> associated Aged Care Principles (there are approximately 23 sets ofPrinciples under the Act which determine <strong>and</strong> describe a range of key responsibilities <strong>and</strong>requirements), provide the legislative framework for the provision of the majority of aged careservices relating to community care, residential care <strong>and</strong> flexible care in Australia <strong>and</strong> isadministered by the Australian Government Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Ageing.This Act replaced the provisions in the National Health Act 1953 (the National Health Act) <strong>and</strong> theAged or Disabled Persons Care Act 1954, wherein nursing homes <strong>and</strong> hostels had been previouslyadministered.The current Act identifies the arrangements to determine:Who can provide care, <strong>and</strong> their roles <strong>and</strong> responsibilities,Who can receive care, <strong>and</strong> their rights <strong>and</strong> responsibilities, What types of aged care services are available, <strong>and</strong> How aged care is funded. 4In addition, under Part 2.1 Division 8-1 <strong>and</strong> 8-3A Approved Provider <strong>and</strong> <strong>Key</strong> Personnel are themain roles defined <strong>and</strong> described in the Act (<strong>and</strong> in the associated Aged Care Principles)particularly relating to Quality of Care, Accreditation, User Rights, Accountability <strong>and</strong> theSt<strong>and</strong>ards relating to residential care, community care <strong>and</strong> flexible care. These roles arefundamental in the legislative accountability for the provision of aged care.2.1.1.3. The Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 <strong>and</strong> Therapeutic Goods Regulations 19904 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act for 2009/201010

The Therapeutic Goods Administration under the Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Ageing administersthe Therapeutic Goods Act 1989, which is the national legislation for the establishment <strong>and</strong>maintenance of systems relating to quality, safety, efficacy <strong>and</strong> availability of therapeutic goods.The Act also provides the framework for the states <strong>and</strong> territories to take a uniform approach inestablishing relevant legislation for the safe h<strong>and</strong>ling of drugs <strong>and</strong> poisons. It is supported by theTherapeutic Goods Regulations 1990.The Poisons St<strong>and</strong>ard 2010 is a legislative instrument under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989. It isalso known as the St<strong>and</strong>ard for the Uniform Scheduling of Medicines <strong>and</strong> Poisons (SUSMP), whichclassify medicines <strong>and</strong> chemicals into Schedules for inclusion in relevant legislation of the states<strong>and</strong> territories. The Poisons St<strong>and</strong>ard also includes model provisions about containers <strong>and</strong> labels, alist of products recommended to be exempt from these provisions, <strong>and</strong> recommendations aboutother controls on drugs <strong>and</strong> poisons. This is a national st<strong>and</strong>ard which is not routinely referred toin the States/Territories legislation.The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) provides timely, reliable <strong>and</strong> affordable access tonecessary medicines for Australians <strong>and</strong> is part of the Australian Government’s broader NationalMedicines Policy. Under the PBS, the government subsidises the cost of medicine for mostmedical conditions. Most of the listed medicines are dispensed by pharmacists, <strong>and</strong> used by thecommunity at home. 5 The PBS is also the primary source of medications being supplied to theelderly in residential aged care.The National Medicines Policy has four key aims 6 :timely access to <strong>and</strong> affordability of medicines for the Australian community,appropriate st<strong>and</strong>ards of quality, safety <strong>and</strong> efficacy for medicines,quality use of medicines, <strong>and</strong>maintenance of a responsible <strong>and</strong> viable medicines industry.2.1.1.4. The Health Practitioner Regulation National LawThe following announcement was made on 26 th March 2008.“COAG also took a major step towards improving Australia’s health system by signing anIntergovernmental Agreement on the health workforce. This agreement will for the first timecreate a single national registration <strong>and</strong> accreditation system for nine health professions:medical practitioners; nurses <strong>and</strong> midwives; pharmacists; physiotherapists; psychologists;osteopaths; chiropractors; optometrists; <strong>and</strong> dentists (including dental hygienists, dentalprosthetists <strong>and</strong> dental therapists). The new arrangement will help health professionals movearound the country more easily, reduce red tape, provide greater safeguards for the public <strong>and</strong>promote a more flexible, responsive <strong>and</strong> sustainable health workforce. For example, the newscheme will maintain a public national register for each health profession that will ensure thata professional who has been banned from practicing in one place is unable to practiceelsewhere in Australia.”5 Dept. of Health & Ageing PBS6 Dept. of Health & Ageing National Medicines Policy11

The Health Practitioner Regulation National Law referred to as The National Law has established anational scheme for the regulation of health practitioners <strong>and</strong> students undertaking programs ofstudy leading to registration as a health practitioner. It applied initially to 10 health professionalgroups from 1st July 2010.It is known as “an applied law” model as the legislative powers are with the states/territories.Queensl<strong>and</strong> has initially enacted the National Law. All of the other states/territories are enactinglegislation to adopt <strong>and</strong> apply the National Law as a law of their own jurisdiction.The Commonwealth does not apply the National Law, but needs to make consequentialamendments to Commonwealth laws to ensure effective interface between the various agencies<strong>and</strong> the national scheme.This Act will be reviewed by jurisdiction under the next section on the States <strong>and</strong> TerritoriesLegislation.2.1.2. States <strong>and</strong> Territories LegislationEvery jurisdiction, except Queensl<strong>and</strong>, has a specific Act relating to medicines, poisons, drugs orcontrolled substances with corresponding Regulations. Queensl<strong>and</strong> utilizes the Queensl<strong>and</strong> HealthAct 1937 as its overarching Act <strong>and</strong> has specific drugs <strong>and</strong> poisons Regulations to spell out thedetail.The relevant Acts <strong>and</strong> Regulations have been reviewed for each State <strong>and</strong> Territory for theelements that are relevant to this <strong>project</strong>. Specific definitions relating to the health professionsare identified in the legislation <strong>and</strong> the steps in medication management, which relate to”prescribing, supplying, dispensing <strong>and</strong> administering”, are noted.A Summary Jurisdictional Table of the Acts <strong>and</strong> Regulations pertaining to medicines, drugs <strong>and</strong>poisons <strong>and</strong> the Acts relating to Health Professionals are available in Appendix A. A jurisdictionalcomparative table relating to the elements of Medication <strong>Management</strong> is available in Appendix B.Detailed tables for each jurisdictional legislation can be found in Appendix C to J.2.1.2.1. Australian Capital TerritoryThe ACT Medicines, Poisons <strong>and</strong> Therapeutic Goods Act <strong>and</strong> Regulations 2008, (effective21/12/2010), <strong>and</strong> the most recent legislation amongst the jurisdictions.The Act <strong>and</strong> the Regulations refer to Health Professionals as defined in the Health PractitionerRegulations National Law (ACT) <strong>and</strong> the Health Professionals Act 2004 <strong>and</strong> defines a residentialaged care facility in accordance with the Aged Care Act 1997.The majority of detail is left to the Regulation to specify who can do what. The terminology of“doctor” is used rather than medical practitioner, with nurse practitioner, nurse, enrolled nurse<strong>and</strong> pharmacist identified with each role qualified viz.:“to the extent necessary to practice(medicine, nursing, pharmacy) <strong>and</strong>, if employed, within the scope of employment”.Of note is that:An Enrolled Nurse, under Schedule 1 Part 1.6, can obtain, possess <strong>and</strong> administermedicines.12

Directors of Nursing <strong>and</strong> Medical Superintendents for a RACF (Residential Aged CareFacility) under Schedule 1 Part 1.11 have particular activities relating to emergencyadministration of medicines.Assistants under Part 5.2 can administer medicines to an “assisted person” under specificconditions.The Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (ACT) effective 01/07/2010 refers to a healthpractitioner’s authorisation under the Act.2.1.2.2. New South WalesThe NSW Poisons <strong>and</strong> Therapeutic Goods Act 1966 (effective 1/07/2010), under Part 1.4specifically defines a nurse practitioner as per the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law <strong>and</strong>under Part 3 s17A (1) details as a person authorised to possess, use, supply, prescribe a poison,restricted substance or drug of addiction. The Act also refers to a Nurse Practitioner beingauthorised in writing by the Director General to possess, use, supply or prescribe. Carers areidentified in the Act with regard to the possession <strong>and</strong> supply of drugs of addiction by carers whoare caring or assisting in the care of another.The Poisons <strong>and</strong> Therapeutic Good Regulation 2008 effective (27/08/2010) under Part 1 s3defines an authorised practitioner as a medical practitioner or a nurse. In Part 2 Div 3 it details thata Medical Practitioner can issue a prescription for a restricted substance <strong>and</strong> a nurse practitionercan only supply a restricted substance in the course of practising as a nurse practitioner.Of note is the reference to a Code of conduct for unregistered health practitioners referred to inthe Public Health Act 1991 <strong>and</strong> cross-referenced to the Health Care Complaints Act 1993.Under the Health Practitioner Regulation Act 2009 – Health Practitioner Regulation National Law(NSW) effective 27/08/2010 there is specific reference to a nurse practitioner as being qualified topractice as a nurse practitioner.2.1.2.3. Northern TerritoryThe Northern Territory Poisons <strong>and</strong> Dangerous Drugs Act (effective 07/07/2010) provides themajority of authority as to legislative roles <strong>and</strong> activities. Part 1 S6 defines medical practitioner asone who practices in the NT <strong>and</strong> a nurse <strong>and</strong> pharmacist as registered under the HealthPractitioners Regulation National Law.Under the Act Parts V <strong>and</strong> VA special reference is made to remote area nurses <strong>and</strong> aboriginalhealth workers to supply medicines <strong>and</strong> it notes that “there is no applicable legislation regardingthe practice of Enrolled Nurses in this regard”.The Act defines supply as including prescribe, administer <strong>and</strong> having in possession for the purposeof supply, prescription <strong>and</strong> administration. It makes specific reference under the Act to Aboriginalhealth worker with the right of practice under the Health Practitioners Act of the NT to possess<strong>and</strong> supply a Schedule 1, 2, 3, <strong>and</strong> 4 substance.There is nothing specific in the Poisons <strong>and</strong> Dangerous Drugs Regulations effective (01/07/2010)relevant to this <strong>project</strong>.The Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (NT) Act 2010 effective 02/07/2010 adopts theQueensl<strong>and</strong> Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009.13

2.1.2.4. Queensl<strong>and</strong>The Health Act 1937 is the overarching Act, however, the Health (Drugs <strong>and</strong> Poisons) Regulation1996 effective (28/01/2011) provides the majority of the legislative direction <strong>and</strong> the most detailregarding the roles of health practitioners.Part 2 Div 2 of the Regulation uses the term “doctors” <strong>and</strong> “physician’s assistant” (under thesupervision of a supervising medical officer) as being able to possess, administer, supply <strong>and</strong>prescribe a controlled drug. Similarly a nurse practitioner can obtain, administer, supply <strong>and</strong>prescribe; a registered nurse can posses <strong>and</strong> administer drugs <strong>and</strong> under s 58A, an enrolled nursecan “possess, administer controlled <strong>and</strong> restricted drugs under the supervision or writteninstruction of a doctor, nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant”. Pharmacists can dispense, sell<strong>and</strong> possess drugs.Similar to the Northern Territory, under Ch 2 Part 2 s59A <strong>and</strong> s164A Indigenous health workers inan isolated area can obtain, possess, administer a controlled <strong>and</strong> restricted drug on oral or writtenorder of doctor, nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant. In addition an “endorsed nurse” in arural hospital or isolated practice area can obtain, supply <strong>and</strong> administer a controlled drug.Ch 2 Part 7 s110 makes particular reference to a nursing home <strong>and</strong> identifies the responsibleperson of a nursing home being the Director of Nursing, a medical superintendent or theregistered nurse in charge <strong>and</strong> under Part 2 s63 they can obtain possess <strong>and</strong> issue controlled <strong>and</strong>restricted drugs.There are no specific definitions in the Regulations for health practitioners as these are detailedunder the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Queensl<strong>and</strong>) Act 2009 which defines ahealth practitioner as one who practises a health profession <strong>and</strong> a registered health practitioner asbeing registered under the Law.2.1.2.5. South AustraliaThe South Australia Controlled Substances Act 1984 effective (28/11/10) defines a medicalpractitioner, a nurse, <strong>and</strong> pharmacist as registered under the Health Practitioner RegulationNational Law.The Act refers to a medical practitioner <strong>and</strong> nurse acting in the ordinary course of his or herprofession being able to sell, supply, administer a prescription drug (not of dependence) <strong>and</strong> apharmacist can dispense the prescription of a medical practitioner.The Controlled Substance (Poisons) Regulations 1996 effective (01/07/10) makes detailedreference to the Uniform Poisons St<strong>and</strong>ard under the TG Act 1989 <strong>and</strong> the Schedules. It describesa “prescriber” as a person who lawfully gives a prescription for a drug. Reference is made to amedical practitioner or nurse relating to supplying <strong>and</strong> administering a drug of dependence <strong>and</strong>details relating to recording.Detailed information listed in the Regulations regarding prescriptions <strong>and</strong> dispensing under Part 4s 25 refers to the responsibilities of the “prescriber”. Part 4 s 27 describes dispensing of apharmacist or medical practitioner.Amendments to Part 5A s 31G <strong>and</strong> 31I in 2009 deleted the word “registered” leaving the word“nurse” <strong>and</strong> provided the ability for an enrolled nurse to administer a drug of dependence.14

Regulation 31I (2) refers to a “designated nurse for a ward of a health service for a particular shift,not the registered nurse in charge of the ward”Under the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (South Australia) Act 2010 a healthpractitioner practises a health profession/registered health practitioner registered under this Law.2.1.2.6. TasmaniaThe Tasmania Poisons Act 1971 effective (01/01/11) provides for the Minister to authorise aregistered nurse to possess <strong>and</strong> supply restricted or narcotic substances <strong>and</strong> for the Secretary toauthorise a nurse practitioner to sell, be in possession of or supply restricted <strong>and</strong> narcoticsubstances. The Governor can also make regulations for the control, supply, prescription,possession of narcotic substances regulating the issue by medical practitioners <strong>and</strong> authorisednurse practitionersThere is also reference to an “authorised nurse practitioner” <strong>and</strong> a “nurse practitioner” in Part 1 s3of the Act with reference to the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Tasmania). A Medicalpractitioner is also referred to as one who must be present in Tasmania.The Act defines supply to include administering <strong>and</strong> dispensing <strong>and</strong> medical practitioners,pharmaceutical chemist <strong>and</strong> authorised nurse practitioner are permitted to sell or supply “in thelawful practice of his or her profession or business”.The Poisons Regulations 2008 effective (01/01/09) Part 1 s3 refers to a health professional as amedical practitioner, a registered nurse, an authorised nurse practitioner, a pharmaceuticalchemist. It also refers to an authorised nurse as one who holds a nursing authority. A medicalinstitution also includes the provision of accommodation for persons who are aged.Under Part 6 s95 EA there is reference to the administration of certain substances by aged careworkers in residential care services under the general supervision or direction of a registerednurse but they also have to have “met the requirements of relevant nationally accredited trainingmodules relating to the administration <strong>and</strong> storage of medication <strong>and</strong> maintain any competencyrequirements of those modules <strong>and</strong> acting in accordance with guidelines approved by theSecretary”. To support this regulation there is a set of “Guidelines for the administration ofcertain substances by aged care workers in residential aged care services” approved by theSecretary of the Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Human Services <strong>and</strong> effective from September 2010. Itdetails the roles for the approved provider, aged care worker, <strong>and</strong> registered <strong>and</strong> enrolled nurses.There is also a similar regulation with respect to aged care workers in community care.Carers are referred to in Part 6 s95G as able to administer or make available for selfadministration,medicinal poison, restricted substance, <strong>and</strong> narcotic substance under a range ofconditions.Part 3 of the Regulations identifies what a medical practitioner, authorised nurse practitioner <strong>and</strong>authorised nurse may not do regarding supply or prescribing. In Part 4 s61 a registered nurse maypossess <strong>and</strong> administer without instructions from a medical practitioner if attending an emergencyin a remote area but has to have undergone an educational program approved by the Nursing <strong>and</strong>Midwifery Board of Australia <strong>and</strong> been endorsed by the same Board. Reference is also made to theMinister granting authority to registered nurses in certain circumstances <strong>and</strong> in Part 4 s60 anenrolled nurse may administer certain substances listed in Schedule 2,3,4,8 if acting with thewritten authority of a medical practitioner or authorised nurse practitioner.15

The Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Tasmania) Act 2010 refers to terms used in thisAct <strong>and</strong> also in the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law set out in the Schedule to theHealth Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 of Queensl<strong>and</strong> have the same meanings inthis Act as they have in that Law.2.1.2.7. VictoriaIn Victoria in the Drugs, Poisons <strong>and</strong> Controlled Substances Act 1981 effective (06/01/11), underPart II 10A reference is made to the administration of medication in aged care services <strong>and</strong> therole of the approved provider to ensure that the registered nurse manages the administration ofany drug of dependence to a resident receiving high level care. Part II S34F <strong>and</strong> S36E make specificreference regarding aged care <strong>and</strong> the permit <strong>and</strong> administration for Schedule 8 drugs. TheApproved provider under the Aged Care Act must ensure that the registered nurse manages theadministration of any drug of dependence Schedule 9.8.4 poisons to a high care resident – <strong>and</strong> inthis regard, must manage the administration in accordance with a Code or guidelines (if any)issued by the Nursing <strong>and</strong> Midwifery Board of Australia under the Health Practitioner RegulationNational Law. (At this stage they have not produced a guideline or code of guidance).There is also a clause in Part II s36F relating to registered nurses having a regard to the relevantcode or guideline (if any) issued by the Nursing <strong>and</strong> Midwifery Board of Australia under the HealthPractitioner Regulations National Law.Under the Act a registered medical practitioner <strong>and</strong> nurse practitioner can administer, supply,prescribe a Schedule 8 poison as well as poisons <strong>and</strong> controlled substances. In addition, apharmacist <strong>and</strong> a registered nurse can possess, use, sell or supply specific drugs.The Act also defines a nurse practitioner, registered medical practitioner, pharmacist, registerednurse as registered under the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law <strong>and</strong> further refers tothe aged care services <strong>and</strong> the Aged Care Act as well as the Commonwealth St<strong>and</strong>ard for uniformscheduling of drugs <strong>and</strong> poisons.Where a registered nurse whose registration is endorsed under the Health Practitioner RegulationNational Law, that person can obtain, use, sell, <strong>and</strong> supply a Schedule 2, 3, 4,<strong>and</strong> 8 approved bythe Minister.The Minister can also approve scope of prescribing rights or supply of poisons for a registerednurse in clinical circumstances.The Drugs, Poisons <strong>and</strong> Controlled Substances Regulations 2006 (effective 26/10/10) defines anaged care service in accordance with the Aged Care Act <strong>and</strong> refers to an authorised registerednurse, <strong>and</strong> an enrolled nurse in accordance with the Heath Practitioner Regulation National Law.Part 2 in the Regulations refers to what a nurse, an authorised registered nurse <strong>and</strong> a pharmacistcan do in the administration of schedule, 4, 8 <strong>and</strong> 9 <strong>and</strong> it also describes what a registered medicalpractitioner <strong>and</strong> a nurse practitioner must not do with regard to the areas relating to administer,prescribe, sell or supply schedules 4 <strong>and</strong> 8.Particular reference is made to an approved provider of an aged care service where there is aresident receiving high care <strong>and</strong> their responsibilities regarding schedule 4, 8 <strong>and</strong> 9 poisons.16

The Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Victoria) Act 2009 adopts the National Law in theSchedule of the Queensl<strong>and</strong> Health Practitioner Regulation <strong>and</strong> defines a health practitioner, amedical practitioner <strong>and</strong> a registered health practitioner.2.1.2.8. Western AustraliaThe WA Poisons Act 1964 (effective 18/12/10) Part 1 defines an endorsed health practitioner,registered under the HPRNL to practise a health profession <strong>and</strong> registration endorsed toadminister, obtain, possess, prescribe, sell, supply or use medicines. It further defines a medicalpractitioner, nurse practitioner <strong>and</strong> pharmacist as registered under the Health PractitionerRegulation National Law (Western Australia).Part III states that a medical practitioner can write, issue or authorise a prescription for the use,sale or supply of a drug of addiction <strong>and</strong> a nurse practitioner is able to possess, use, supply orprescribe any poison.The Governor can also make regulations to regulate the issue, dispensing <strong>and</strong> supply ofprescriptions by medical practitioners <strong>and</strong> nurse practitioners.Under the Poisons Regulations 1965 (effective 20/11/10) Part 6, an authorised person is defined<strong>and</strong> a physician is described as recognised by the Medical Board. A registered nurse has themeaning in the Nurses <strong>and</strong> Midwives Act 2006 (however this has been repealed). NIMC is referredto as the National Inpatient Medication Chart.Supply includes distribution <strong>and</strong> selling. Administration does not include supplying, <strong>and</strong>dispensing means supply of a medicine in accordance with a prescription.A medical practitioner, nurse practitioner <strong>and</strong> pharmacist can supply schedule 4 poisons <strong>and</strong> amedical practitioner <strong>and</strong> pharmacist can procure <strong>and</strong> dispense schedule 8 <strong>and</strong> drugs of addiction.In part 6 it refers to a registered nurse employed in a hospital having authority to procure <strong>and</strong>administer poisons under the instructions of a medical practitionerThe Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (WA) Act 2010 in its Schedule defines a healthpractitioner, a medical practitioner, <strong>and</strong> a registered health practitioner.2.1.2.9. Where are the Gaps?In analysing the jurisdictional legislation <strong>and</strong> extracting the relevant aspects, the following <strong>issues</strong>have been identified: A variety of terminology <strong>and</strong> definitions are used with no consistent approach. Forexample ‘doctor’ is used in some legislation, ‘medical officer’ <strong>and</strong> ‘medical practitioner’used in others <strong>and</strong> ‘health practitioner’ in others with some being interchangeable. Somedefine a nurse practitioner, others define a nurse or registered nurse as well as authorisedperson, <strong>and</strong> there are only a few references to enrolled nurses. Even within thejurisdictional legislation, it is difficult to decipher the roles <strong>and</strong> definitions.Further roles are referred to relating to carers, assistants, physician assistants <strong>and</strong> otherhealth workers in some jurisdictions <strong>and</strong> others are silent. Specific references to aged careworkers <strong>and</strong> approved providers are noted in some jurisdictions but not in others.17

There is no uniform identification <strong>and</strong> definition of the health practitioners’ roles relatingto their legislative responsibilities in who can prescribe, supply, dispense <strong>and</strong> administermedicines, poisons <strong>and</strong> drugs. There is also inconsistency in the definitions of themedication management stages.The use of the terminology relating to medicines, poisons <strong>and</strong> drugs appears variable in thetitles of the legislation <strong>and</strong> within the legislation.Efforts have been made to reference the Health Practitioner Regulation National Laws, butagain there is no consistency in this approach.2.2. Guidance documents2.2.1. Sources <strong>and</strong> types of documents reviewedDocuments were identified initially through internet searches, the use of Pub Med <strong>and</strong> a variety offollow-up contacts. The eventual range of document sources was:• Government – departments, statutory authorities, committees, commissioned reports -State/Territory, Australia, US & UK.• Professional organisations – nursing, medical, pharmacy, unions.• Industry organisations – aged care, pharmacy, General Practice, health – State/Territory,<strong>and</strong> Australia-wide.• Others – Provider organisations <strong>and</strong> Non Government Organisations (NGOs) such as elderadvocacy, consumer, particular interest <strong>and</strong> specific disease focus (e.g. Alzheimer)organisations.Interviews about aged care medication practice <strong>and</strong> workforce <strong>issues</strong> were also held with ProfTrisha Dunning, Chair in Nursing (Barwon Health) Deakin University, <strong>and</strong> Ms Belinda Moyes, CEOCountry Health South Australia <strong>and</strong> former Chair of the National Nursing <strong>and</strong> Nursing EducationTaskforce.While the resulting list of documents could easily be supplemented, the range <strong>and</strong> contentrepresents the most important documents, <strong>and</strong> a meaningful cross-section of the academicliterature in English.About sixty percent of the documents identified related specifically to medication managementprinciples <strong>and</strong> practice, the remainder relating to workforce, <strong>and</strong> broad professional practice <strong>and</strong>health worker education matters.2.2.2. Medication <strong>Management</strong> documents2.2.2.1. Government DocumentsDocuments from Australian <strong>and</strong> State/Territory governments comprised the largest group, apartfrom journal articles, found in the document search.Comprehensive guidance on Medication <strong>Management</strong> in aged care was found in the APAC(Australian Pharmaceutical Advisory Council) publications which address medication managementin residential aged care facilities <strong>and</strong> in the community, <strong>and</strong> continuity of medication18

management. These Guidelines have the endorsement <strong>and</strong> support of Australian <strong>and</strong>State/Territory health <strong>and</strong> ageing authorities: the nursing, medical <strong>and</strong> pharmacy professionalorganisations, <strong>and</strong> of aged care <strong>and</strong> general practice industry peak organisations.The Guidelines for Medication <strong>Management</strong> in Residential Aged Care Facilities is under review;however the appendices to their documents are not to be included in the review <strong>and</strong> areconsidered by the industry to be outdated <strong>and</strong> not reflective of industry workforce or practice.Other guidance documents which were, until July 2010, widely used by nurses in the field, werethose developed <strong>and</strong> distributed by the former nurse registration boards in each of the states <strong>and</strong>territories. There was, however, no uniformity across these documents. This was also the casewith the various health departments’ guidance documents developed for staff of department runfacilities to address medication management (generally or in aged care) <strong>and</strong> the various roles.The range of these documents covered inter alia,general St<strong>and</strong>ards, Codes <strong>and</strong> Scopes of Practice for Registered Nurse (RN) Enrolled Nurse(EN) or Midwife practice,St<strong>and</strong>ards specifically for RN <strong>and</strong>/or EN medication management,policies on delegation by RNs to ENs <strong>and</strong>/or other unlicensed health workers (variouslytitled), guidance for medication management for high care residents in aged care,position statements <strong>and</strong> policies on dose administration aids (DAA), <strong>and</strong> on use ofcomplementary <strong>and</strong> alternative medicines.Some of these documents included references to:the applicable jurisdiction’s drugs <strong>and</strong> poisons regulation,national health practitioner legislation, <strong>and</strong>codes <strong>and</strong> guidelines such as the APAC Guidelines.Queensl<strong>and</strong> Health has produced a very comprehensive h<strong>and</strong>book on “The Health (Drugs <strong>and</strong>Poisons) Regulation 1996 - What Nurses Need to Know”. The Victorian Department of HumanServices, in partnership with GP Divisions <strong>and</strong> service providers, has published a comprehensiveguide to implementing the APAC Guidelines for Residential Care.The Victoria Department of Health has produced the Drugs <strong>and</strong> Poisons Controls in Victoria,managing drugs in residential Aged Care <strong>and</strong> <strong>Key</strong> requirements for nurses in residential Aged CareServices.Neither the new Nursing <strong>and</strong> Midwifery Board of Australia, (nor the newly tasked <strong>and</strong> renamedAustralian Nursing <strong>and</strong> Midwifery Accreditation Council) has developed st<strong>and</strong>ards or guidelineswhich specifically address medication management or aged care. Nurses must now underst<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> apply the relevant national nursing competency <strong>and</strong> registration st<strong>and</strong>ards, <strong>and</strong> decisionmaking frameworks, <strong>and</strong> their organisation’s own policies, to inform their practice, accountability<strong>and</strong> delegation of medication management in aged care.2.2.2.2. Professional Organisation documentsThe main documents identified were the:19

Australian Nursing Federation (ANF)/Royal College of Nursing Australia (RCNA) NursingGuidelines - Aged Care settings,several relevant Professional Practice St<strong>and</strong>ards;three guidance documents on Residential Medication <strong>Management</strong> Reviews (RMMR) in agedcare facilities from the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia;Position Statement from the Australian Society for Geriatric Medicine; <strong>and</strong>Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Guidelines for the medical care ofolder persons in residential aged care facilities (The Silver Book) - Chapter 3.Victoria Department of Health has produced the Drugs <strong>and</strong> Poisons Controls in Victoria,managing drugs in residential Aged Care <strong>and</strong> <strong>Key</strong> requirements for nurses in residential AgedCare Services“The Silver Book’ makes clear references to the three sets of APAC guidelines, <strong>and</strong> theANF/RCNA Nursing Guidelines are incorporated in the APAC Guidelines for Residential Care.2.2.2.3. Industry Organisation documentsRelevant guidance documents were found from several industry organisations. The AustralianGeneral Practice Network (AGPN) has released a set of information <strong>and</strong> tools for RMMRs. Severalindividual GP Divisions have developed Resource Kits for Medication <strong>Management</strong> in aged care,usually based on the APAC guidelines, <strong>and</strong> initiated or led several Quality Use of Medicines<strong>project</strong>s run in partnership with service providers. One example is the MedGap <strong>project</strong> whichdeveloped systems <strong>and</strong> tools to ensure safe <strong>and</strong> prompt continuity of medication for patientsmoving between acute hospitals <strong>and</strong> either home or residential care.The Pharmacy Guild has also produced a range of sound information documents on aspects ofmedication management in aged care.The two Aged Care industry peak bodies <strong>and</strong> the Aged Care Industry IT Council have initiated a<strong>project</strong> to implement an electronic medication management system in aged care facilities, which isoutlined in the 2009 publication “Case for Electronic Medication <strong>Management</strong> in Aged Care –Executive Summary”.All these guidance documents discussed briefly above, vary in depth <strong>and</strong> specificity but clearlyreflect good if not best, practice. Many include well-designed forms <strong>and</strong> tools to support <strong>and</strong> assistsafe practice in aged care <strong>and</strong> community settings.2.2.2.4. Academic <strong>and</strong> Overseas LiteratureA wide ranging search identified a range of documents <strong>and</strong> tools that were reviewed in greaterdetail. Of particular note were the following points:a Pharmaceutical Care Package for assessing <strong>and</strong> providing shared pharmaceutical care in thecommunity;St<strong>and</strong>ards for Medicines <strong>Management</strong> from the Nursing <strong>and</strong> Midwifery Council UK,(comparable to those of the former Western Australian <strong>and</strong> South Australian nurse registrationboards);20

The Centre for Policy on Ageing (UK) reports <strong>and</strong> tools. London-based <strong>project</strong>s to improvemedication management through a “Single Assessment Process”; <strong>and</strong>The nurse registration board for Irel<strong>and</strong> Comprehensive Guidance to Nurses <strong>and</strong> Midwives onMedication <strong>Management</strong>.The following themes were identified from these overseas documents. However Australian AgedCare services do not collect national data <strong>and</strong> so little is known on actual medication error rates.Medication errors (which can occur at many points from prescription through dispensing,packaging, storage <strong>and</strong> administration) <strong>and</strong> adverse events occur in residential aged carefacilities <strong>and</strong> among the elderly in the community with rates of 20% to 30% (of medicinesadministered) with up to 75% of residents in aged care affected. Errors were highest forpsychotropic, diabetes, <strong>and</strong> anticoagulant medications. Contributing factors included:o complex medication regimes with high numbers of individual drugs prescribed;o prescribing, charting, dispensing, <strong>and</strong> supply errors <strong>and</strong> inconsistencies;o medication information transfer problems where patients moved between settings(home, hospital, residential care);o workload levels <strong>and</strong> interruptions to those administering medications;o inadequate medication monitoring systems;o certain formulations (creams, liquids, aerosols) <strong>and</strong> changes to formulations (crushingtablets, emptying capsules).Strategies identified to reduce errors included:o Dose Administration Aids (although some studies suggest these cause errors),o integrated computerised prescription, order <strong>and</strong> entry (CPOE) systems linking theprescriber, dispenser <strong>and</strong> administrator,o electronic health records (with some qualified support),o pharmacist involvement in medication management systems for both residential <strong>and</strong>community care,o multidisciplinary medication reviews <strong>and</strong> medication management systems,o pharmacist training of direct care staff in aged care medications <strong>and</strong> systems,o medication monitoring systems, <strong>and</strong>o reducing medication management staff workload <strong>and</strong> interruptions.The conclusions that can be drawn from this literature review include:There is no uniformity of guidance on medication management for nurses in aged careamongst the states/territories.APAC guidelines have differing authoritative credibility amongst professionals <strong>and</strong> healthauthorities.Little is known of actual medication error rates in Australian aged care.Multidisciplinary medication review <strong>and</strong> management systems; staff education bypharmacists, CPOE <strong>and</strong> other electronic systems <strong>and</strong> other tools may reduce medicationerrors.21

Clarity of legalities, <strong>and</strong> simplicity of guidance on medication management, as well as clarityaround nurses’ delegations to, <strong>and</strong> roles of, personal care workers in medicationmanagement are all necessary to improve the safety <strong>and</strong> efficiency of medicationmanagement systems.There is a growing interest in researching <strong>and</strong> furthering intersectoral collaboration toachieve greater consistency <strong>and</strong> shared “good practice” in managing medication for, <strong>and</strong>with, older people.The literature suggests the following gaps in medication management need to be addressed:Consistent, authoritative <strong>and</strong> widely applied guidance for all players in medicationmanagement, on systems <strong>and</strong> practices which promote safe, effective <strong>and</strong> efficientmedication management.Effective multidisciplinary medication review <strong>and</strong> monitoring systems to assist medicationmanagement players to identify <strong>and</strong> address risk <strong>and</strong> problem areas, <strong>and</strong> to benchmarkpractice across the aged care sectors.Consistent clinical governance systems in both residential <strong>and</strong> community careorganisations, which would bring the guidance, the medication systems, <strong>and</strong> theirevaluation <strong>and</strong> improvement together.2.2.3. Workforce Issues Documents2.2.3.1. Government DocumentsThe Productivity Commission Annual Reports on Government Services – Aged Care chapters -presented useful industry profiles <strong>and</strong> some workforce statistics for consecutive years, along withsome commentary on changing factors in the aged care environment.Release of the Draft Report in January 2011 on its Inquiry - Caring for Older Australians -providesfurther confirmation of previous findings (<strong>and</strong> the anecdotal evidence provided to the consultantson key workforce <strong>issues</strong> through the survey), particularly:problems of staff supply,recruitment <strong>and</strong> retention, <strong>and</strong> training, contributed to by low status/image <strong>and</strong> inequitable(compared with acute hospitals) pay <strong>and</strong> conditions in the aged <strong>and</strong> community sectors.The draft report also points to an exacerbation of these problems as the community ages, <strong>and</strong> theavailable pool of younger workers declines, <strong>and</strong> notes the dominant influence of regulatory <strong>and</strong>compliance approaches on the aged care service culture.These findings are consistent with those identified in the workforce <strong>issues</strong> section of the Report ofthe Senate St<strong>and</strong>ing Committee on Finance <strong>and</strong> Public Administration on Residential <strong>and</strong>Community Aged Care in Australia, <strong>and</strong> with the 2001 Final Report of the Victorian Department ofHuman Services’ Nurse Recruitment <strong>and</strong> Retention Committee.22

Department of Health <strong>and</strong> Ageing documents provided information on Aged Care legislation <strong>and</strong>st<strong>and</strong>ards. There were also some State/Territory health authority documents, particularly fromVictoria, which outlined the role of the department in aged care, jurisdiction over residentialfacilities which do not fall under the national Aged Care Act, <strong>and</strong> staffing guidance, frameworks<strong>and</strong> indicators for quality in their public sector residential aged care facilities (which also fall underthe national Aged Care Act).The Department of Education, Science <strong>and</strong> Training, (predecessor to the current Department ofEducation, Employment <strong>and</strong> Workplace Relations), commissioned the National Review of NursingEducation, which examined a wide range of workforce <strong>and</strong> education matters. It commissioned areview Australian Aged Care Nursing: A Critical Review which examined:the aged care workforce profile;future dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> supply;education <strong>and</strong> training;recruitment <strong>and</strong> retention in the overall aged care workforce.There was a substantial body of documents from national education, training, <strong>and</strong> employeerelations departments <strong>and</strong> authorities. The most current of these were detailed curriculadeveloped <strong>and</strong> regularly reviewed by the Community Services <strong>and</strong> Health Industry Skills Councilfor Certificates III <strong>and</strong> IV in Aged Care, Health Services Assistance <strong>and</strong> Enrolled Nursing.Medication management has not been a core unit in these courses, <strong>and</strong> this has contributed tovariable skills <strong>and</strong> training needs of those working in the field.The Nursing <strong>and</strong> Midwifery Board of Australia intends that all Enrolled Nurses will haveundertaken approved study in medication administration, <strong>and</strong> they note that “this will require arange of strategies to ensure a consistent scope of practice across the Enrolled Nurse workforce”(NMBA, Enrolled Nurses <strong>and</strong> Medicine Administration: Explanatory Note).Studies <strong>and</strong> reports by, <strong>and</strong> for, the National Nursing <strong>and</strong> Nursing Education Taskforce (N 3 ET)identify <strong>and</strong> address factors for current shortages in health workforce, recruitment <strong>and</strong> retentionstrategies through e.g. Myth Busters, <strong>and</strong> implementation of recommendations from the NationalReview of Nursing Education including:instituting qualifications <strong>and</strong> suitability checks for personal care workers,working towards consistent regulation of nursing;collaboration for improvement in aged care;developing a national decision making framework for nurses; <strong>and</strong>introducing consideration of scopes of practice for nurses.The National Health Workforce Taskforce identifies work programs which would have addressedall the following workforce planning <strong>issues</strong> which are as relevant to aged care as to the rest of thehealth <strong>and</strong> community services sectors. For example:23

ensuring <strong>and</strong> sustaining supply,workforce distribution that optimises access to health care <strong>and</strong> meets health needs for allAustralians,health environments being places in which people want to work,ensuring the health workforce is always skilled <strong>and</strong> competent,optimal uses of skills <strong>and</strong> workforce adaptability.A constant theme in many documents, <strong>and</strong> in this study <strong>and</strong> ACSA’s earlier survey amongst itsstate peak body members, is the importance to an effective <strong>and</strong> efficient workforce of getting theskill mix “right”. In 1990 a Deakin University team was commissioned by the Minister for Aged,Family <strong>and</strong> Health Services to research <strong>and</strong> reported on an “Optimal Skills Mix for Desired ResidentOutcomes in Non-Government Nursing Homes”. This work identified a mix of RN, EN <strong>and</strong> personalcare workers, with nursing leadership, as being effective, but proposed that further work wasrequired to increase the proportion of diversional therapists (however titled) <strong>and</strong> further clarifythe role <strong>and</strong> training of enrolled nurses. In 2004, the National Aged Care Alliance (comprisingindustry, professional, consumer <strong>and</strong> aged-care specific interest organisations) published“Principles for Staffing Levels <strong>and</strong> Skills Mix in Aged Care Settings” to guide the field in itsworkforce strategies, <strong>and</strong> the Government as funder <strong>and</strong> regulator in developing a funding modelwhich would enable the Principles to be implemented.The 2005 National Aged Care Workforce Strategy proposed actions to address leadership <strong>and</strong>management; education, training <strong>and</strong> development; a responsive workforce; status <strong>and</strong> image;<strong>and</strong> effective linkages. Determining what progress was made, <strong>and</strong> any points at which it mayusefully be reinvigorated may be worth pursuing.2.2.3.2. Professional Organisation documentsMost of the professional organisations’ documents are from the Australian Nursing Federation(ANF) <strong>and</strong> its State/Territory branches. These documents address skill mix <strong>issues</strong> <strong>and</strong> credentialingof personal care workers by registered nurses, <strong>and</strong> provide guidance to nurses on roles <strong>and</strong>relationships with other staff, including other nurses <strong>and</strong> personal care workers.The ANF has also published a booklet – Balancing risk <strong>and</strong> safety for our community – whichdiscusses the <strong>issues</strong> relating to personal care workers in the health <strong>and</strong> aged care systems, <strong>and</strong>proposes seven options to address these. This issue was frequently raised in both this survey, <strong>and</strong>the 2008 Aged <strong>and</strong> Community Services Australia (ACSA) survey. The ANF options range from selfregulation<strong>and</strong> licensing to co-regulation.2.2.3.3. Industry Organisation documentsACSA has a medication management policy which seeks:a national framework,a sound training system,an Overseas Workers’ employment policy,24

a Workforce Framework which outlines strategies to address aged care image, attracting<strong>and</strong> retaining staff, funding to support quality care, development of models of care, usinglabour-saving technology, securing a national industry-wide workforce plan, <strong>and</strong> supportingaged care providers to become preferred employers.These reflect the workforce <strong>issues</strong> already cited <strong>and</strong> support ACSA’s goal of using labour-savingtechnology as outlined in the document “The Case for Electronic Medication <strong>Management</strong> in AgedCare” referred to in 4.2.2.3 above.2.2.3.4. Academic LiteratureMost of the academic literature reviewed focussed on nursing, with much of it examining nursingfrom a quality of care <strong>and</strong> staff/mix perspective against ownership type (chain, private, not forprofit & public). In some instances, there is limited comparison able to be made with theAustralian system.Articles on alternate <strong>and</strong> innovative models of care highlight the need for non-traditional skill <strong>and</strong>occupation mixes within multidisciplinary approaches, <strong>and</strong> emphasise empowerment <strong>and</strong> enablingof staff <strong>and</strong> residents through very effective nursing leadership.Other articles addressed recruitment, retention <strong>and</strong> rates of turnover of nursing <strong>and</strong> other carestaff, <strong>and</strong> revealed rates that are fairly consistent with reported rates <strong>and</strong> experience in Australia.Recruitment <strong>issues</strong> associated with the relatively low pay, status <strong>and</strong> image of aged care appear tobe problems also in the UK, Europe <strong>and</strong> North America.2.2.3.5. Main observations <strong>and</strong> inferences from these documents <strong>and</strong> articles• Aged care work is unpopular with RNs <strong>and</strong> ENs. Factors contributing to this are the low status<strong>and</strong> pay compared with the acute sector, the heavy workloads <strong>and</strong> regulatory <strong>and</strong> compliancedem<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> <strong>issues</strong> with staffing levels <strong>and</strong> skill mix particularly in residential care.• Many national initiatives have been aimed at improving aged care worker education/training,promoting workforce planning & development, <strong>and</strong> clarifying roles, functions <strong>and</strong> appropriatestaffing levels <strong>and</strong> mix in aged care.• Some national initiatives are underway or proposed at present, but seem, as yet, to have“borne no fruit”.• There is little agreement between professions, the aged care industry <strong>and</strong> government as toeffective staffing patterns <strong>and</strong> skills mix, though there are examples of effective models whichcould be replicated or trialled by service providers.• There is a good range of resources, suggestions <strong>and</strong> <strong>project</strong>s to use or guide providers, butfinding out about them is difficult as there are so many players (Governments, professionalbodies, researchers) dealing with different aspects of workforce development <strong>and</strong> planning,<strong>and</strong> supporting different policy <strong>and</strong> education strategies.25