Biological Control of Diseases on Golf Course Turf - USGA Green ...

Biological Control of Diseases on Golf Course Turf - USGA Green ...

Biological Control of Diseases on Golf Course Turf - USGA Green ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

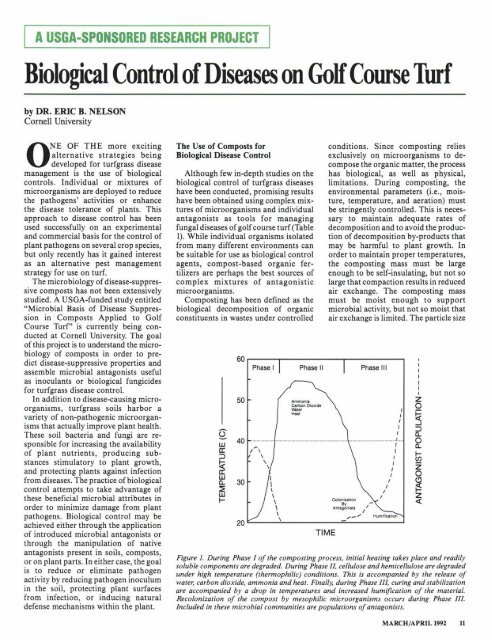

A <strong>USGA</strong>-SPONSOREDRESEARCH PROJECT<str<strong>on</strong>g>Biological</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>trol</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Diseases</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Golf</strong> <strong>Course</strong> <strong>Turf</strong>by DR. ERIC B. NELSONCornell UniversityONE OF THE more excitingalternative strategies beingdeveloped for turfgrass diseasemanagement is the use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> biologicalc<strong>on</strong>trols. Individual or mixtures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>microorganisms are deployed to reducethe pathogens' activities or enhancethe disease tolerance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plants. Thisapproach to disease c<strong>on</strong>trol has beenused successfully <strong>on</strong> an experimentaland commercial basis for the c<strong>on</strong>trol <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>plant pathogens <strong>on</strong> several crop species,but <strong>on</strong>ly recently has it gained interestas an alternative pest managementstrategy for use <strong>on</strong> turf.The microbiology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> disease-suppressivecomposts has not been extensivelystudied. A <strong>USGA</strong>-funded study entitled"Microbial Basis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Disease Suppressi<strong>on</strong>in Composts Applied to <strong>Golf</strong><strong>Course</strong> <strong>Turf</strong>" is currently being c<strong>on</strong>ductedat Cornell University. The goal<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this project is to understand the microbiology<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> composts in order to predictdisease-suppressive properties andassemble microbial antag<strong>on</strong>ists usefulas inoculants or biological fungicidesfor turfgrass disease c<strong>on</strong>trol.In additi<strong>on</strong> to disease-causing microorganisms,turfgrass soils harbor avariety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> n<strong>on</strong>-pathogenic microorganismsthat actually improve plant health.These soil bacteria and fungi are resp<strong>on</strong>siblefor increasing the availability<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> plant nutrients, producing substancesstimulatory to plant growth,and protecting plants against infecti<strong>on</strong>from diseases. The practice <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> biologicalc<strong>on</strong>trol attempts to take advantage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>these beneficial microbial attributes inorder to minimize damage from plantpathogens. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Biological</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>trol may beachieved either through the applicati<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> introduced microbial antag<strong>on</strong>ists orthrough the manipulati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nativeantag<strong>on</strong>ists present in soils, composts,or <strong>on</strong> plant parts. In either case, the goalis to reduce or eliminate pathogenactivity by reducing pathogen inoculumin the soil, protecting plant surfacesfrom infecti<strong>on</strong>, or inducing naturaldefense mechanisms within the plant.The Use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Composts for<str<strong>on</strong>g>Biological</str<strong>on</strong>g> Disease <str<strong>on</strong>g>C<strong>on</strong>trol</str<strong>on</strong>g>Although few in-depth studies <strong>on</strong> thebiological c<strong>on</strong>trol <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> turfgrass diseaseshave been c<strong>on</strong>ducted, promising resultshave been obtained using complex mixtures<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> microorganisms and individualantag<strong>on</strong>ists as tools for managingfungal diseases <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> golf course turf (TableI). While individual organisms isolatedfrom many different envir<strong>on</strong>ments canbe suitable for use as biological c<strong>on</strong>trolagents, compost-based organic fertilizersare perhaps the best sources <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>complex mixtures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> antag<strong>on</strong>isticmicroorganisms.Composting has been defined as thebiological decompositi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> organicc<strong>on</strong>stituents in wastes under c<strong>on</strong>trolled605020Phase IPhase IITIMEc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. Since composting reliesexclusively <strong>on</strong> microorganisms to decomposethe organic matter, the processhas biological, as well as physical,limitati<strong>on</strong>s. During composting, theenvir<strong>on</strong>mental parameters (i.e., moisture,temperature, and aerati<strong>on</strong>) mustbe stringently c<strong>on</strong>trolled. This is necessaryto maintain adequate rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>decompositi<strong>on</strong> and to avoid the producti<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decompositi<strong>on</strong> by-products thatmay be harmful to plant growth. Inorder to maintain proper temperatures,the composting mass must be largeenough to be self-insulating, but not solarge that compacti<strong>on</strong> results in reducedair exchange. The composting massmust be moist enough to supportmicrobial activity, but not so moist thatair exchange is limited. The particle sizeCol<strong>on</strong>izati<strong>on</strong>ByAntag<strong>on</strong>istsPhase IIII40IIII'j' .30IIIIIII/IFigure 1. During Phase I <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the composting process, initial heating takes place and readilysoluble comp<strong>on</strong>ents are degraded. During Phase I/, cellulose and hemicellulose are degradedunder high temperature (thermophilic) c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. This is accompanied by the release <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>water, carb<strong>on</strong> dioxide, amm<strong>on</strong>ia and heat. Finally, during Phase IIL curing and stabilizati<strong>on</strong>are accompanied by a drop in temperatures and increased humificati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the material.Recol<strong>on</strong>izati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the compost by mesophilic microorganisms occurs during Phase III.Included in these microbial communities are populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> antag<strong>on</strong>ists.IIIIIIIZo~::)a..o a..~~ Zo~ ~Z

12 <strong>USGA</strong> GREEN SECTION RECORDii;, ".:P-: ,ii' ':,,I ~'eli49m<strong>on</strong>al Spp.GaeW71anriomyces Spp.Bhialophora r;adicicolaComplex mixturesTJ(p~u,laphacorrhizalrichoderma spp.COInpl~x rnixtures:ii',,!-';,'i' ,'; ..••:.. ,m:;,; iF: di, '~n LOntario; CanadaN. CarolinaNew York, MarylandNew YorkOntario, CanadaSouth CarolinaNew YorkIllinois, OhioOhioColoradoNew YorkNew York, PennsylvaniaPennsylvaniaNew YorkNew YorkNew YorkN. CarolinaColoradoAustraliaAustraliaAustraliaOntario, CanadaMassach usettsNew York<strong>Turf</strong>grassesCreeping BentgrassjAnnual BluegrassCreeping Bentgrass jAnnual BluegrassKentuckyPerennialKentuckyRyegrassCreeping BentgrassjAnnual BluegrassPerennialCreepingBluegrassRyegrassBluegrassBentgrassj<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the material must be small enough toprovide proper insulati<strong>on</strong>, but not sosmall that it limits air exchange.When all <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the envir<strong>on</strong>mental andphysical c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s are optimized, compostingshould proceed through threedistinct phases (Figure 1) involving (1)a rapid rise in temperature, (2) a prol<strong>on</strong>gedhigh-temperature decompositi<strong>on</strong>phase, and (3) a curing phase wheretemperatures and decompositi<strong>on</strong> ratedecrease. These three phases <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decompositi<strong>on</strong>are accompanied by successi<strong>on</strong>s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both mesophilic (moderatetemperature)and thermophilic (hightemperature)micr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>lora. Each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thesemicrobial communities makes an importantc<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> to the nature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> thecomposted material. Failure to maintainenvir<strong>on</strong>mental c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s favorablefor adequate microbial activitycould jeopardize the quality <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the finalproduct.In general, the l<strong>on</strong>ger the curingperiod, the more diverse the col<strong>on</strong>izingmesophilic micr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>lora. These micr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>loraare the most important in suppressingturfgrass diseases. At the presenttime, unfortunately, there is noreliable way to predict the diseasesuppressiveproperties <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> composts,since the nature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these col<strong>on</strong>izingmicrobial antag<strong>on</strong>ists is left to chanceand determined largely by the micr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>lorapresent at the composting site.Applicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> composted materialcan suppress turfgrass diseases (Table2). M<strong>on</strong>thly applicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> topdressingc<strong>on</strong>taining as little as 10 pounds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>suppressive compost per 1,000 squarefeet were effective in suppressingdiseases such as dollar spot, brownpatch, Pythium root rot, Typhulablight, and red thread. Reducti<strong>on</strong>s inseverity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pythium blight, summerpatch, and necrotic ringspot also havebeen observed in sites receiving periodicapplicati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> composts. Of particularbenefit is the impact <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> l<strong>on</strong>g-term compostapplicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> root-rotting pathogensin soil. Populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> soil-bornePythium species are generally not suppressedfollowing traditi<strong>on</strong>al chemicalfungicide applicati<strong>on</strong>s, but can bereduced <strong>on</strong> putting greens receivingc<strong>on</strong>tinuous compost applicati<strong>on</strong>s in theabsence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> any chemical fungicideapplicati<strong>on</strong>s. Also, heavy applicati<strong>on</strong>s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compost (approximately 200 poundsper 1,000 square feet) to putting greensin late fall are effective not <strong>on</strong>ly insuppressing winter diseases, such asTyphula blight, but also in protectingputting surfaces from winter ice andfreezing damage.

(Left) Figure 2. Field research plotsimmediately after applying topdressingsamended with various composts andorganic fertilizers.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Biological</str<strong>on</strong>g> suppressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> dol/ar spot <strong>on</strong> a creeping bentgrass / annual bluegrass putting green 32 days after applicati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> selected compostsand organic fertilizers. (Left photo) The plot <strong>on</strong> the left was untreated, while the <strong>on</strong>e <strong>on</strong> the right was treated with approximately 10poundsper 1,000 square feet <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an organic fertilizer. (Right photo) The plot <strong>on</strong> the bottom was left untreated, while the <strong>on</strong>e <strong>on</strong> the top was treatedwith a poultry litter/cow manure compost mixture at the rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> approximately 10pounds per 1,000 square feet.Composts prepared from differentstarting materials, as well as those atdifferent stages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decompositi<strong>on</strong>, varyin the level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> disease-suppressi<strong>on</strong> andin the spectrum <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> diseases that arec<strong>on</strong>trolled. This is primarily a result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the microbial variability am<strong>on</strong>gdifferent composts and differences inthe quality <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> organic matter present ina compost at various stages <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> decompositi<strong>on</strong>.Although microbial activityis necessary for disease-suppressiveproperties to be expressed in most composts,the specific nature <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> disease suppressivenessis, in general, unknown.In our research, several aspects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theecology <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> key compost-inhabitingantag<strong>on</strong>ists are being investigated. Forexample, the ability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> microbialantag<strong>on</strong>ists to establish and survive inturfgrass ecosystems is necessary forbiological c<strong>on</strong>trol to occur. The interacti<strong>on</strong>s<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> antag<strong>on</strong>ists with other soilorganisms, and the soil or plant factorsaffecting optimum biological c<strong>on</strong>trolactivity, will be important in developingstrategies with compost-basedmaterials. In additi<strong>on</strong>, these organismsmay serve as indicators <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> how l<strong>on</strong>g tocompost a material before it can becertified to be disease-suppressive.Research aimed at understanding thefate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> antag<strong>on</strong>istic organisms in soilsand <strong>on</strong> plants following compostapplicati<strong>on</strong>s will aid in understandingwhy composts fail at certain times andlocati<strong>on</strong>s. This research also shouldhelp predict the compatibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> compostsand their resident antag<strong>on</strong>istswith other pesticides and culturalpractices comm<strong>on</strong>ly used in turfmanagement.Individual microbial antag<strong>on</strong>istsfound in soils, composts, or in associati<strong>on</strong>with plants can, in many cases,suppress disease at levels typicallyachieved with composts or from use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>fungicides (Figure 4). Due to theextremely close link between theirfuncti<strong>on</strong> and performance, however,<strong>on</strong>e cannot readily predict antag<strong>on</strong>isticMARCH/APRIL 1992 13

Effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> various strains <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Enterobacter cloacae and the fungicide metalaxyl <strong>on</strong> thesuppressi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Pythium blight <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> perennial ryegrass in growth chamber experiments. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Diseases</str<strong>on</strong>g>everity was rated <strong>on</strong> a scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 to 5, for which 1 equals no foliar blight and 5 equals 100percent foliar blight. A - N<strong>on</strong>treated; B - Drenched with metalaxyl (750 pg a.i./ml);C - Treated with E. cloacae strain EcCT-50l; and D - Treated with E. cloacae strain E6.(From Nels<strong>on</strong> & Craft, 1991).behavior without an understanding <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the microbial traits important inpathogen or disease suppressi<strong>on</strong>. It als<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ollows that the performance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>antag<strong>on</strong>ists could be effectively enhancedif their functi<strong>on</strong> was clearlyunderstood.The traits necessary for an antag<strong>on</strong>istto suppress turfgrass disease are unknown;however, a number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> traitsare currently being investigated. Forexample, these traits include the ability<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> antag<strong>on</strong>ists to produce fungicidalcompounds or compounds that makenutrients unavailable to pathogens.Other traits include the ability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>antag<strong>on</strong>ists to parasitize pathogens,col<strong>on</strong>ize plant parts, and compete withpathogens for resources in soil and <strong>on</strong>plants.The use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> topdressing materialsamended with disease-suppressivecomposts or organic fertilizers hasreceived some acceptance by turfgrassmanagers as. an attractive diseasec<strong>on</strong>trolalternative. Many compostedmaterials and organic fertilizers arecommercially available from distributorsor municipal waste treatmentfacilities. Preliminary research hasshown that use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> composts and organicfertilizers for turfgrass disease c<strong>on</strong>trol isec<strong>on</strong>omically and technologicallypractical and, in some instances, canprovide reas<strong>on</strong>able levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> diseasec<strong>on</strong>trol. In the few cases that have beenexamined with some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these materials,a reducti<strong>on</strong> in fungicide use has accompaniedthe adopti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this biologicalc<strong>on</strong>trol strategy.Before disease-suppressive compostsbecome widely accepted and used fordisease c<strong>on</strong>trol, the principal problem<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a compost not being c<strong>on</strong>sistentlysuppressive from year to year, batch tobatch, or from <strong>on</strong>e site to the next mustbe solved. <strong>Turf</strong>grass managers andcompost producers agree that the futuresuccess <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these materials in commercialturfgrass management depends up<strong>on</strong>the ability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> producers to providematerials with predictable levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> diseasec<strong>on</strong>trol. Gross variati<strong>on</strong> in diseasesuppressivequalities <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> composts cannotbe tolerated because end-users needto be assured that every batch <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>compost used specifically for diseasec<strong>on</strong>trol will work every time.Unfortunately, we do not yet knowhow to predict the suppressive activity<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> certain composts without actuallytesting them in field situati<strong>on</strong>s. Anumber <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tests have been developed todetermine compost maturity and degree<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> stabilizati<strong>on</strong> for the purpose <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>reducing the variability in physical andchemical properties. Very little <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theresearch, however, has been designed todirectly' assess microbiological aspects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> maturity and disease suppressiveness.Currently, predictive tests based<strong>on</strong> levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> microbial activity andorganic matter quality are beingexplored through this research projectas potential tools for predicting composts'disease-suppressive properties.Back to the Basics for <strong>Golf</strong> and the Envir<strong>on</strong>mentby GEORGE B. MANUELAgr<strong>on</strong>omist, Mid-C<strong>on</strong>tinent Regi<strong>on</strong>, <strong>USGA</strong> <strong>Green</strong> Secti<strong>on</strong>UOKING ahead into this decade<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> envir<strong>on</strong>mental c<strong>on</strong>cerns, it is adistinct possibility that superintendentsthroughout the country willexperience restricti<strong>on</strong>s in the applicati<strong>on</strong>or availability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> pesticides. To preparefor these future reducti<strong>on</strong>s, thereis a need to search for alternatives tomake grasses healthier and less chemicallydependent. The successful superintendentin the 1990s will be <strong>on</strong>e whois able to combine proven agr<strong>on</strong>omicpractices <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the past with some <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>14 <strong>USGA</strong> GREEN SECTION RECORDtoday's technology. A "back to basics"approach will help you meet theenvir<strong>on</strong>mental challenges at yourdoorstep.Three <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the most important factorsin maintaining healthy turf are propernutriti<strong>on</strong>, reas<strong>on</strong>able cutting heights,and regular aerati<strong>on</strong>. In order to preparea fertilizati<strong>on</strong> program, the soilfrom a porti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the greens, tees, andfairways should be tested annually. Forbest results, it is preferable to c<strong>on</strong>tinuewith the same testing laboratory toachieve a c<strong>on</strong>sistent evaluati<strong>on</strong> yearafter year.When test results are received, theyshould be examined closely and comparedto the previous year's analysis.Adjustments can then be made toprovide optimum growing c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>sfor the turf. In particular, potassiumand phosphorous levels should beclosely m<strong>on</strong>itored. Soil potassium canbe depleted due to rapid uptake by theturf as well as its tendency to be leachedthrough the soil pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ile. This results in