Machicolation: some postscripts. - Castle Studies Group

Machicolation: some postscripts. - Castle Studies Group

Machicolation: some postscripts. - Castle Studies Group

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

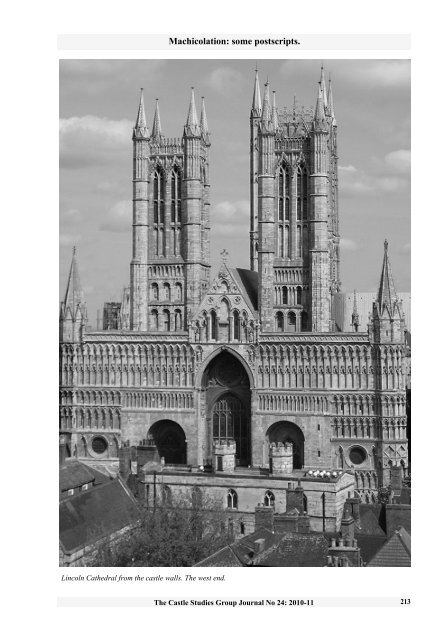

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Lincoln Cathedral from the castle walls. The west end.The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 213

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.<strong>Machicolation</strong>: Some <strong>postscripts</strong>John HarrisSince I wrote the piece “<strong>Machicolation</strong>:History and Significance” 1 I have comeacross <strong>some</strong> examples of machicolationwhich, though they may not alter any of thearguments discussed in that piece, do addinteresting detail. The first example comesfrom the earliest days of castle building andtouches on the invention of machicolation.It has long been known that up inthe intrados of the two flanking arches ofthe three on the west front of Lincoln Cathedral,there are slots that look very likeslot machicolation, but there has been surprisinglylittle comment on them. Theseslots are accessed from small chambers atsecond floor level, which reinforces theidea that they could serve as machicolation;it is assumed that there was a similar slotover centre portal, which is of course higherthan the others and has been altered;access to this could have been from a wallwalkat parapet level.In 1986, an article by RichardGem 2 was published which suggested thatoriginally the west end of the cathedral wasindeed fortified. This first phase of thework was begun by Bishop Remigius in1072 and consecrated in 1092. It may seemsurprising that a cathedral should be fortified,especially when it is so close to a royalcastle of much the same date, but such atheory does explain these slots, for which itis difficult to find any convincing explanationother than machicolation. Other aspectsof the building, in particular whatmust be a latrine, suggest a non-ecclesiasticalpurpose.In an article published in 1997,David Stocker and Alan Vince 3 take upGem’s idea and put it into the context of theevolution of the Roman town into the mediaevalUpper City of Lincoln. They argueconvincingly that for a time the buildingthat is now the west end of the cathedralserved as the keep of a castle built byBishop Remigius in his rôle as temporallord. When Bishop Alexander moved themilitary base of the bishop’s secular responsibilitiesto Newark in the secondquarter of the 12th century, the keep wasincorporated into a cathedral nave, whichwas then rebuilt after a fire in the 1140s.They also make a convincing case for thetower being completed near the start ofRemegius’s building programme, perhapsby 1075, so this machicolation (and indeedthe keep itself) is very early.Much of the argument aboutwhether this is <strong>some</strong> kind fortified westworkto a cathedral or a separate bishop’skeep lies outside the scope of this piece. 4Few writers seem to regard the machicolationas remarkable in itself, apart from itsimportance in suggesting the defensiblenature of the building, but I think it is andit seems clear that the idea of slot machicolationexisted in England nearly a centurybefore we find it in a more developed format, say, Krak des Chevaliers, and this seemsworthy of comment. It has been suggested 5that one possible origin of slot machicolationis the double gateways formed of twoseparated planes found in Moorish Spain asearly as the mid-10th century.Here in Lincoln we have machicolationused in association with gateways; itseems a simple connection. But BishopRemigius was a Norman; he had held postsin Fécamp and Dorchester but seems tohave had no connection with MoorishSpain, or with what is now Iraq, where slotmachicolation can be found dating from thelate 8th century. But might his designerhave been more cosmopolitan than he was?It would be exciting to find that the bishophad <strong>some</strong>one in his retinue with experienceof military architecture in Spain.Stocker and Vince draw parallelsbetween this Lincoln tower and the WhiteTower in London as examples of the earliestphase of Norman hall-keep building inThe <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 214

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Fig.1. Top: Illustration by W. T Ball to Richard Gem’sarticle (Architectural History 44: 2001).Fig.2. Right: View of flanking portal of Lincoln Cathedral,looking upward to show machicolation. Photo:John HarrisFig.3. Below:Hypothetical reconstruction of originalplans of west front of Lincoln cathedral (ArchitecturalHistory 44: 2001)The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 215

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.England. 6 The Lincoln “keep” was <strong>some</strong>34m by 19m; the White Tower is 36m by31m. They publish floor plans of a hypotheticalreconstruction based on Gem’swork 7 . Lincoln differs of course in havinga relatively undefended narthex-likeground-floor space (or undercroft) withthree doorways to the west, doorwayswhich may have given access to the cathedralor <strong>some</strong> pre-existing church 8 but alsoserved to add modelling to the building asarcading does at Norwich and the WhiteTower, but more dramatically and splendidly.The original arrangements to theeast, abutting the church are unknown. It istempting to wonder whether the vulnerabilityof these doorways prompted the thinkingthat led to including the machicolation.The slots could have been used to pourwater on to fires lit against timber doorsthat were larger and more accessible thanthose of a typical keep, as well as to shootor drop missiles on to besiegers.The only mention of anything likemachicolation in classical writing(Vegetius in the late 4th century) recommendsslots as a way of dousing such firesrather than as a way of attacking besiegers.It is speculation, but as a cleric Remegiuswould have had access to classical worksand just possibly could have read Vegetius,especially as he was a bishop with militaryresponsibilities. Although the actual formof these slots is different from the typeapparently envisaged by Vegetius,Remegius’s adoption of his suggestionmight be an introduction of machicolationunconnected with its evolution in the eastand in Spain.As Stocker and Vince say“…Remegius was behaving not as a bishop,but primarily as a conventional greatNorman Lord….symbolising his Lordshipin the conventional Norman way by constructinga massive, dominant ....donjon……” In doing so, he appears to havecreated a building form with special needsand to have introduced or invented thedevice of machicolation to answer theseneeds.At the other end of the mediaevaltimescale, there are late-ish examples ofmachicolation that are worth examining forthe light they can throw on the use of thedevice in the final years before its phasingout.Each example is worth knowing aboutin itself.Soncino castle, the Rocca Sforzesca,near Milan was built in about 1473(Figs. 4, 5). It has rectangular towers and acontinuous run of machicolation along thewalls all in a style similar to many northItalian castles of the period, but it also hasa single round angle tower with two layersof machicolation, one higher than the generalrun of wall-top machicolation and onelower. This tower is higher than the wallsand in proportion unlike the torrioni of arocca such as that at Imola which is of avery similar date. There the towers havebeen reduced to the height of the walls inresponse to attack by cannon. We mustassume that the Soncino tower was builtwith an awareness of the potential of gunpowderartillery, in both defence and attack,although it may represent anon-the-hoof change to the design 9 . Whilethere seems to be a wish here to demonstrateestablished authority by a continueduse of machicolation and other mediaevalarchitectural forms in the castle overall, inthe use of a circular tower, more resistantto cannon fire than the rectangular formthat had been common in North Italy, andin the use of batter at the base of the towersand walls, there is a recognition of the needfor change. The round tower is to all intentsand purposes a torrione, despite its proportionsand its height, although one that placesimportance on machicolation.This strange arrangement of doubled-upmachicolation might be used tosupport almost any theory about the purposeof machicolation: an enthusiasm forThe <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 216

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Fig 4. General view of Soncino castle. (Rocca Sforzesca), built in 1473 for Galeazzo Maria Sforza.Fig 5 Double-machicolated round tower at Soncino castle. View from the south.The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 217

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Fig 6 Typical Venetian chimneys of the 15 th century. Depicted from theHealing of the Madman (detail), from the Miracles of the True Cross Series,1494; tempera on canvas, 365 x 389 cm Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice.Vittore Carpaccio (c.1460 - 1525/1526).dropping missiles vertically, with here anattempt to double the efficiency of thetactic or a demonstration that machicolationhas become so important symbolicallythat two rows of it were better than one.The town of Soncino is on the river borderbetween Sforza land and land that hadrecently been appropriated by Venice: thedouble-machicolated tower can be seen asfist-shaking defiance. Symbolism was certainlypresent in the castle’s design; Venicewas to build a new town – Orzinuovi –on the other side of the river in the 1540s,very up to date in its design,as a similar show ofstrength. This tower mightalso be taken to reinforcethe supposition that flaringoutat the top of a tower hasa deep-seated aesthetic importance.In this case, it isdone twice rather than justonce. To my eye, the resultis neither elegant nor exciting,but oddly, the towerrather resembles a characteristicVenetianchimneystack, 10 but muchlarger and with an additionalflourish. This style ofchimney itself seems to reflectthis same fondness forflaring-out of towers at thetop (Fig. 6).At the base of this towerthere is a marked batter,beneath a cordon. This is anarrangement common tomost torrioni of the period,the batter being introduced(or re-introduced) to resistcannonballs and mining.The continued use ofmachicolation after the introductionof such battershas been much discussed,but here the doubling of themachicolation suggests ithas an importance even with a batter. Thelower range of machicolation is of coursehard up against the wall of the tower, theupper one roughly above the outer edge ofthe batter. 11 Although together the tworanges would certainly clear any attackersfrom the foot of the tower, it is more likelythat the machicolation was not primarilyintended to do this, but would be used withmissile-shooting weapons, to command amuch wider area. Battering rams and escaladehad largely fallen out of use with theintroduction of cannon and the base of aThe <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 218

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Fig. 7. Detail of the tower in the background of the Francesco Giorgione ‘Castelfranco Madonna’ (inset). TheMadonna and Child Between St. Francis and St. Nicasius, was executed around 1503. It is housed in La Pala of theCathedral of Castelfranco, Giorgione's native city, in the Veneto, northern Italy.The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 219

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.tower was unlikely to be attacked unless abreach had been opened up. Such a talltower, weakened by the openings of machicolationhalfway up in addition to those atthe top, as well as other arrow or gun loops,must have been very vulnerable to cannonfire, just what was not wanted. This was nota design that would have a future.A strange arrangement, but thereis <strong>some</strong> evidence that this was not unique.In the background of Giorgione’s CastelfrancoMadonna of around 1503, there is astrange tower apparently with a run ofmachicolation just over halfway up, whatappears to be a hourding or a drop-boxmachicolation in association with a doorway(or it might just be a balcony) furtherup and at the top, what appears to be atimber oversailing construction of hourdingsdiagonally propped in timber, with apitched roof (Fig. 7). The whole looks ratherlike a structure that has been extendedupwards and adapted over time. Possibly itis Giorgione’s fantasy and no more, but it issuggestive that multiple layers of machicolationjust might have existed in Venetianterritory as well as in Sforza lands.At the heart of Sforza territory, thecastle in Milan (1450 onwards) shows whatmight be thought of as the very opposite ofthe tower at Soncino: a robust machicolatedtower (the Torre del Filarete,) sportingabove its principal roof a smaller tower,again with machicolation and on top of thatin turn, wedding-cake like, two more turrets,or a belvedere and a lantern (Fig. 8).The lower range of machicolationis clearly usable. The upper range, if weagree that firing missiles diagonallythrough the openings is a way of usingmachicolation, could be of use too, but ifdouble the firepower was wanted, <strong>some</strong>more suitable building form could surelyhave been found. Missiles dropped fromthis upper towerlet would of course kill orinjure fellow defenders. The comparativelysmall projection of the upper machicolationreinforces the idea that this is in fact adecorative element, part of an architectonicwhole; the upper parts, slender and tall, arevulnerable to cannon fire. The fightingplatform incorporating the lower machicolationseems to be two storeys high, withtwo levels of cannon ports as well as crenellation.A demonstration of power andstatus is what this tower is all about.The tower-on-tower arrangementdiminishing upwards is of course quitecommon, but few other towers are quite soelaborate. In Siena, the Torre del Mangiahas makes a gesture towards machicolationon its upper recessed storey, but this isclearly decorative. The tower of the Palazzodella Signoria in Florence might justhave been useful in defence after thepalazzo’s courtyard had fallen, as well asadding to the first line of defence, but thecourse beneath the topmost crenellation ismerely decorative.These Milanese and Tuscan examplesof doubled machicolation diminishingupwards seem to be largely aboutshow, but they do have a functional ancestor,a tower at Lanuvio in Lazio, apparentlybuilt in the early 15th century, possiblyby altering and extending a round Romantower (Fig. 9). Here the relative proportionsof lower and upper towers and thelines of fire that are implied suggest thatboth ranges of machicolation could havebeen used at the same time, the upper rangebeing used to shoot at an angle of <strong>some</strong> 20 ofrom the vertical over the heads of thedefenders below. There has been considerablerepair, restoration and fairly recent(WWII) damage; many of the original detailsare now unclear (indeed, apparentlyaltered) but the tower’s appearance is formidable.There probably are other examplesof this arrangement, but there aremany more of simple, un-machicolatedsmaller towers rising above the crenellationof towers, which is the commoner arrangement.The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 220

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Fig 8. The Torre del Filarete at Milan castle. Photo: Neil GuyThe <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 221

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Fig. 9. Lanuvio. Early 15th century tower, built possiblyby developing a Roman tower.Equally interesting and perhapsclearer in what it tells us is a tower ortorrião at Azemmour in Morocco built bythe Portuguese in about 1515 (Fig. 10). Ithas a flattened oval plan and machicolationthat both harks back to Château Gaillardand forward to the forts at Genoa and theMartello towers at Pembroke Dock. Alsoincorporated into the tower are small armsslits and very large cannon ports. The toweris without batter and the machicolationis formed of what might be described aschutes, perhaps a metre and a half long thatdie back into the thickness of the tower,rather than being engineered by a bracketing-outabove them; the form is rather likethe reverse side of a cheese grater. This isdifferent from any design of machicolationpreviously built.It is an odd piece of design: machicolationcontinues to be used at quite a latedate, but is remodelled. Remodelling suggeststhat even as late as this, <strong>some</strong>thinglike machicolation was the close defencedevice of first choice for <strong>some</strong> people andit had not become merely symbolic anddecorative; this does not even look likeearlier versions of machicolation. It may bethat the building material available in Moroccoprecluded the use of corbelled machicolation,even of the structurallyundemanding type we see at Soncino andMondavio. 12 Mortar made from the locallime was considered to be too brittle - thePortuguese imported massive amounts oflimestone for burning - and may not haveallowed the use of cantilevers, but it may bethat this is a thoughtful reassessment quiteunconnected with constructional problems,of what a small arms gunport needs to be ifit is to defend the approaches to a tower orwall, foreshadowing, as hinted, the latere-use of machicolation in the nineteenthcentury.Handguns (and at this date, stillcrossbows) must surely be what this machicolationwas intended for: missilesdropped vertically through the openingshere would only roll down the slopingchute and would have been very inaccurate.Moreover, one can see up through themachicolation openings from locations onthe ground <strong>some</strong> distance from the tower,strongly suggesting a line of fire reachingthat far. The Portuguese call this devicevãos para tiro mergulhante - “holes forplunging fire,” a phrase that confirms, inthe use of the word tiro, an assumption thatshooting is what this machicolation wasused for. This design of machicolation actuallymakes it very difficult to cover thebase of the tower but it does lessen thevulnerability of machicolation to destructionby gunfire. In fact, this tower is at are-entrant angle of the curtain wall and itsbase can be swept from the wall. This doesnot apply to other parts of the town withThe <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 222

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Fig 10. A torrião at Azemmour in Morocco, showing unusual machicolation and blocked-up artillery embrasuresFig 11. So-called Machicouli Tower, Wurzburg, showing diagonal chute machicolation beneath decorative bracketedmachicolationThe <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 223

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.this arrangement: there is also at least onestraight run of the qasba wall designedwith both similar machicolation and gunports.By this date, it could be argued thatthe use of cannon by attackers meant that tocover of the base of the wall against ramsor escalade had become less important. AtAzemmour, this realisation has had an effecton design. Fire from openings such asthese could interdict besiegers’ cannon andtroops approaching any breach in the wallopened by their cannon.The form of machicolation foundhere - chutes for handguns diagonallypiercing the thickness of a wall – is alsofound three hundred or so years later on theso-called Machicouli Tower at theMarienburg Fortress at Würzburg, 13where working embrasures are placed beneathfalse bracketed machicolations apparentlyused to suggest historical authorityand power and to introduce as degree ofdecoration (Fig. 11). Is this use of falsemachicolation a hangover from late mediaevaltimes, or a precursor of the Romanticnineteenth century view of fortification,when German military architecture adoptedpseudo-mediaeval motifs in a big way?Finally, a look at the Villa Giustinianat Roncade in the Veneto. 14 Theword “villa” is significant, because here weseem to have an authentic case of machicolationunquestionably used for only showand possibly to suggest a seigneurial authority,although work done with surprisingthoroughness (Figs 12, 13). The villa complexwas apparently built over a protractedperiod, between the early 1510s and itscompletion in about 1529. It consists of acompletely unfortified house, fashionablyRenaissance in style, surrounded by whatappears to be a defensible wall with rectangularcorner towers and a gateway withtwin round towers equipped with machicolation,the whole enceinte finished off withswallow-tailed Ghibelline merlons. Theform is known as a castello in the regionand dates from at least the early fifteenthcentury and originally effectively fortified.The arrangements at the Villa Giustinianseem to suggest defence against more thanwolves and roaming footpads, but in therear wall of the enclosure is an openinginto a garden, completely without a gate ofany kind (at least by 1536, when a map wasdrawn) moreover the main gate is a triumphalarch and lacks most of the devices ofa fortified gateway. The front wall has nowallwalk at all and the side walls are theouter walls of farm buildings.It hardly seems that this is a seriouslydefensible complex at all, and indeed,in Tuscany, for example, similarcomplexes of villa and farm had been builtwith only the slightest token show of castle-likedefensibility. Lorenzo de’ Medici’sVilla Poggio a Caiano dating from about1485, has what are no less than summerhousesas its corner “towers” and a palacedoorway for its gate, while maintaining theappearance of an enclosure. 15Although probably not meant tobe used in anger, the defensive elements ofthe towers at Roncade are designed withcare and are convincing. You could drop orshoot through the machicolation openingsif you wanted to and the brackets are boldand business-like, resembling Tuscanwork of the 1480s, for instance. They arenot at all like the obviously decorativeversions at the Castel Nuovo in Naples, forinstance. Then we notice that the gatehousetowers with their machicolation arevirtually reproduced in miniature by thechimneys of the villa and the drawing of1536 shows <strong>some</strong>thing very similar. 16 Thegeneral profile of the chimneys is again thetypical Venetian type. There may havebeen restoration, but it does look as if thiseffect was always intended. There is <strong>some</strong>thingvery like a joke here and moreover asuggestion that forms are being used playfully,perhaps as fashion items.The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 224

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.Fig. 12. A view of the front towered entrance and enclosing wall of the Villa Giustinian at Roncade.Fig. 13. A view of the Villa Giustinian showing principal facade and villa chimneys.The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 225

<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.The villa was built after the marriageof Hieronimo Giustinian to AgnesinaBadoer: a union of two of the wealthiest butalso the oldest families in Venice. They didnot need the trappings of feudal architectureto disguise parvenu status, althoughpossibly the move from Venice to terrafirma did call for the suggestion of longtermland ownership and of being part of along-standing mainland aristocracy; therehad been a castle on the site centuries before.Perhaps the Venetian chimneys showa need not to cut ties with the city. The villahas clearly been restored and has sufferedfrom decay. The merlons of the walls andgatehouse have been rebuilt but the cornertowers lack merlons and most of theirmachicolation brackets have been brokenaway. The present merlons, Ghibelline aswe have seen, are puzzling – the Venetianswere not known for espousing the Imperialcause and the drawing of 1536 seems toshow square merlons. 17 But we can be reasonablysure that no restoration would haveconverted merely token machicolation into“real” machicolation: this was built thisway.There has never been much doubtthat machicolation was used as a symbol ofpower and authority even when circumstancesmade it impracticable to use, northat it changed through full-size but nonfunctionalmachicolation into a merely decorativemotif. One thing that Roncade tellsus is that we cannot be sure that the pace ofthis change corresponded with the abandonmentof mediaeval, pre-gunpowderstyles of military architecture. At Roncade,we are in a world where a client is makingchoices about what his building will sayabout him and apparently enjoying it. Andthis seems to include a joke!End Notes1. CSG Journal 23, 2009-10, p. 191.2. The Journal of British Archaeological AssociationConference Transactions No. VIII. Thearticle is entitled “Ecclesia Pulchra, EcclesiaFortis.” The title derives from Henry of Huntingdonwho had written about the strength ofthe church in “Historia Anglorum” (c.1129-33.) Gem’s article is noted by Pevsner andHarris in “Buildings of England: Lincolnshire.”(It should be stated at this point that thepresent writer is not the John Harris whoco-authored the Pevsner book.) Gem had proposedthe idea in 1978 in a paper presented tothe Society of Antiquaries and in 1984 in theessay “English Romanesque Architecture” inthe catalogue to the exhibition “English RomanesqueArt 1066-1200” at the HaywardGallery. Mediaeval Archaeology 41. The articleis entitled “The Early Norman <strong>Castle</strong> atLincoln and a Re-evaluation of the OriginalWest Tower of Lincoln Cathedral.”3. This piece is immensely interesting in manyways, not least in its study of the use made bythe Normans of Roman fortified sites. Seealso “In Hoc Signo” by Anthony Quiney inArchitectural History Vol. 44 (2000) whichdiscusses the design of the west front as awhole. Quiney suggests there may have beentimber “fighting platforms” spanning the portalsin addition to the machicolation. Onemight think that anyone on the platforms wasat risk from the machicolation above. Remigius(who also appears as Remi) had foughtat Hastings. The tricky questions of militarysymbolism in cathedral architecture and thesignificance of the triple portal entrance areraised in Otto von Simpson “The Gothic Cathedral.”4. Stocker and Vince convincingly argue for thekeep, as has been suggested. There is an argumentthat the decorative frieze on the westfront is part of a conversion of a militarybuilding into a religious one.5. Harris, op cit. p. 193, amongst others. See thearticle by Peter Burton in CSG Journal 22, p.228 et seq., photos 4 and 11.6. Work certainly could be done to place thisstructure in the overall typology of early hallkeeps. See, for instance, the work published in“A Suggested Dual Origin for Keeps” by MW Thompson in Fortress 15, November 1992.7. If we are accept the general idea of thisbuilding being a keep, there may be scope forsuggesting alternatives to these reconstructions.The question of the east wall is difficultto resolve.The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 226

8. This problem - whether the tower, accepted as akeep, was the way into the church or not - iscrucial. If it was specifically a keep, why thethree portals into a ground floor space? If thenarthex to the church, what defensive measureswere present in the church building to equalthose on the west elevation? There may be <strong>some</strong>function of the undercroft ground floor spacethat we are not aware of.9. There are odd features to the wall near thejunction with this tower which may be connectedwith a change in the design. I have made thepoint that rectangular towers were more commonin Italy in the Middle Ages, but this is notan absolute rule. My attention has been drawn toa tower, probably originally of the late 14th orearly 15th century, at the Rocca di Sanvitale diFontanellato which is remarkably like the roundSoncino tower, except that it lacks the upperrange of machicolation. It seems very likely thatit was once a shorter tower, up to the machicolationlevel – it almost matches other towers at therocca, round ones – but has been raised inheight, retaining the machicolation, when it wasintegrated into the residential range of a newcastle. If a similar thing happened at Soncino,the relative levels of the machicolation on theround tower and the rest of the castle seem onlyto explained by the round tower having beenpart of an earlier, lower enceinte, with roundtowers, perhaps of an early 15th century date,retained and raised for <strong>some</strong> reason when a newcastle with higher walls and square towers wasbuilt. That would account for the anomalousround tower, but raises not only the question ofwhy the round tower was kept and altered, butother questions as well, such as the strangelylow height of the supposed original and why theoriginal, lower range of machicolation was notdemolished when the tower was raised.10. As seen in paintings such as Carpaccio’s“Miracle of the Reliquary of the Holy Cross” of1494, for instance.11. The angle of the batter here rather dispels thesuggestion that vertically dropped missiles wereintended to be deflected into a horizontal trajectory.12. Undemanding because the brackets cantileverout in small steps, minimising stresses on thematerial.<strong>Machicolation</strong>: <strong>some</strong> <strong>postscripts</strong>.13. (a.k.a Maschikulis) Built 1724-29, the architectwas Maximilian von Welsch and the engineerBalthasar Neumann. The tower itself isround, too, which reinforces the mediaevalfeel.14. See Paul Holberton “Palladio’s Villas” forthe history of this villa (although no-one suggeststhat its unknown architect was Palladio.)See also Carolyn Kolb Lewis “The VillaGiustinian at Roncade,” (New York 1977 -Lewis argues that the architect was TullioLombardo) and the review of this book inJSAH vol. 39, no. 3, (Oct. 1980) by GeorgeHersey.15. At Lorenzo’s grandfather Cosimo’s countryhouses or farms of <strong>some</strong> four decades earlier:Cafaggiolo and Carregi for instance, it is thehouse that has the trappings of fortification,albeit with false machicolation. At Poggio,the house is clearly and ostentatiously unfortified.16. This similarity is the more evident becausethe towers are shown in the map of 1536 ashaving low-pitched tiled roofs over theircrenellation, a feature that is often found todayon other Italian castles, but the date forwhich is usually difficult to decide.17. Although an 18C drawing shows these merlonsas having the Ghibelline form. SomeVenetian villas, though, do seem to have hadGhibelline merlons from their earliest days,for instance the Villa Porto (a.k.a the CastelloPorto-Colleoni) in Thiene, a Venetian villawhich seems to have been built with them inthe late 1450s. They are built into the masonryof the wall of an additional storey added inabout 1520 but still visible (intentionally so?).Other similar merlons on the building havebeen restored and might not be authentic. Itmay be that the move from city to countrysidesuggested to Porto a retrospective wish todemonstrate a Ghibelline alliance, along witha feudal past. But it may also be the case thatsuch merlons had simply acquired a non-politicaldecorative significance and became afashion statement; you can see earringsformed of the CND motif worn on CoronationStreet. The model might have been the VaticanBelvedere of 1484-7 (see Ackerman,“Distance Points – Essays in Theory andRenaissance Art and Architecture” 1991, pp.303-320.) But there are plenty of unquestionableexamples of thoughtless restoration usingswallow tails, and Italian restorers doseem to have had a penchant for the shape.The <strong>Castle</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Journal No 24: 2010-11 227