Third Edition Spring 2013 - Institute of East Asian Studies, UC ...

Third Edition Spring 2013 - Institute of East Asian Studies, UC ...

Third Edition Spring 2013 - Institute of East Asian Studies, UC ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Editorial CommissionAlison YeeKelsi MacklinStephanie ChamberlainChristopher RobertsonTara YarlagaddaAdvisorsMartin BackstromSharmila ShindeBonnie WadePr<strong>of</strong>essor ReviewersCo-Chair and CoordinatorCo-Chair and Editor-in-ChiefDirector <strong>of</strong> Publicity and LayoutGraduate EditorPublicity and Editing Assistant<strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>Group in <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>Group in <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>BERKELEY STUDENT JOURNAL OFASIAN STUDIESEDITION 3 - SPRING <strong>2013</strong>Robert P. GoldmanJunko HabuT.J. PempelAlexander von RospattDarren ZookSouth & Southeast <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>AnthropologyPolitical ScienceSouth & Southeast <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>International & Area <strong>Studies</strong>,Political ScienceFunded By The National Resource Center at the <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>East</strong><strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> and the Group in <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>.<strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>East</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> and the Group in <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>,University <strong>of</strong> California Berkeley

TABLE OF CONTENTS1 How Does Ethnicity Affect CurrentcHINA-Malaysia Relations?Kankan Xie First Year Graduate, South and South<strong>East</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> Sudies26 Constructing “Culture”Mark Portillo Undergraduate Senior, Political Science41 The Success <strong>of</strong> Environmental NGOs inSuharto’s IndonesiaRachel Phoa Undergraduate Junior, Political Scienceand Enviornmental Science55 The Relevance <strong>of</strong> Kautilya’sArthashastraRamanathan Veerappan Undergradaute Sophomore,Physics and South <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> MinorSpecial Thanks: The Berkeley Student Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong> wouldlike to thank Martin Backstrom, Sharmila Shinde, Bonnie Wade, RobertP. Goldman, Junko Habu, T. J. Pempel, Alexander von Rospatt, DarrenZook. Your support and contributions have been invaluable. Thisjournal would not be possible without the effort, energy, and supportyou have provided us.Logo: Image credits to the followng web entities via CreativeCommons, archnophobia, Indo Dreamin, www.nimpscher.de70 Ainu and the Metaphors <strong>of</strong> Indigeneity:Land, History, Science, Law and BodiesValerie Black First Year Graduate, Group in <strong>Asian</strong><strong>Studies</strong>87 Not so Singular: Laicization in JapaneseBuddhism and Parallels in South AsiaRobert Bowers Curl First Year Graduate, Group In<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>

Dear Reader,We are pleased to present the third volume <strong>of</strong> the BerkeleyStudent Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Studies</strong>. The journal developed as an effortto provide a forum to showcase, connect, and enrich youngscholars studying issues related to Asia at <strong>UC</strong> Berkeley.In this volume, Valerie Black uses metaphor to explore thestatus <strong>of</strong> the Ainu in Japan, as well as the relationship <strong>of</strong> metaphorto perception. Robert Bowers Curl examines some unique characteristics<strong>of</strong> Japanese Buddhism as it shifted away from a TheravadaBuddhist model towards a Newar Buddhist model. Rachel Phoalooks at the role environmental non-governmental organizationsplayed under the regime <strong>of</strong> Suharto in Indonesia as a result <strong>of</strong>international pressure and environmental damage. Mark Portillouses photography as a tool to analyze how a government garnerspower and uses that power to create cultural memory, specificallyregarding the Vietnam War. Ramanathan Veerappan sheds lighton the themes found in the ancient Indian text Arthashastra byKautilya, its relevance to modern institutions, as well as the text’seconomic and political strategies echoed in later Western schools<strong>of</strong> thought. Kankan Xie looks at the role <strong>of</strong> ethnicity in China andMalaysia’s bilateral relationship, and its impact on politics andeconomics.The journal strives to serve as a platform to encourage theemergence <strong>of</strong> student scholarship on Asia. It is a unique bridgebetween undergraduate and graduate scholars, and we hope tocontinue this tradition through your future submissions and support.-The Editors

How Does Ethnicity Affect CurrentChina-Malaysia Relations?Kankan XieAbstractThis paper aims to analyze the current China-Malaysia bilateral relationshipfrom the perspective <strong>of</strong> ethnicity by drawing attention to Malaysia’sethnic-based domestic politics. Unlike in many other countries where Chinesediasporic communities account for only a relatively small portion <strong>of</strong> the totalpopulation, the proportion <strong>of</strong> ethnic Chinese in Malaysia represents a sizableminority <strong>of</strong> 24.6%. In order to take care <strong>of</strong> Chinese interests domestically whilereducing the country’s dependence on its ethnic Chinese minority in dealing withChina-related issues, the Malay-controlled Malaysian government has activelyadopted a series <strong>of</strong> implicitly pro-China policies in both bilateral and multilateralspheres. This paper first examines how the Chinese diaspora fits within theMalaysian domestic political climate in general. Based on a survey conducted in2009, this paper discusses how Malaysian people’s perceptions <strong>of</strong> China vary accordingto their ethnic background. Following this, it demonstrates the ways inwhich economic and cultural issues affect China-Malaysia relations as the country’sdomestic political struggles proceed. This study concludes that there is amismatch between Malaysian Chinese’s relatively high economic status and theirsubordinate role in Malaysia’s patronage system. On the one hand, this allowsthem to benefit tremendously from close China-Malaysia bilateral ties and thusgain substantial leverage in domestic politics, but on the other, makes them furthermarginalized in inter-governmental dialogues.Since the establishment <strong>of</strong> diplomatic relations in 1974, thebilateral relationship between China and Malaysia has been developingsmoothly and steadily. The friendly ties between the twocountries have become increasingly close over the subsequent 38years. According to data published by China’s Ministry <strong>of</strong> ForeignAffairs in 2011, bilateral trade rose by 42.8% and its total amountreached $74.2 billion USD in 2010, which was the highest amongall ASEAN countries. China’s imports from Malaysia reached $50.4billion USD and its exports to Malaysia totaled $23.8 billion, an increase<strong>of</strong> 55.9% and 21.3% respectively compared to the 2009 data.As <strong>of</strong> the same year, Malaysia had directly invested $5.6 billion USDin China. By comparison, China’s direct investment in Malaysia was$440 million. Driven by this vibrant economic cooperation, bilateralexchanges <strong>of</strong> people are also more frequent than before. Morethan one million people from each country visited the other in2010. 1 For Malaysia, China has become a major source <strong>of</strong> tourists.The two countries have signed a number <strong>of</strong> agreements aimed atdeepening bilateral cooperation in various fields, including technology,culture, education and military. Despite minor issues, suchas a territorial dispute over the Spratly Islands in the South ChinaSea, the development <strong>of</strong> the China-Malaysia relationship is generallyquite positive, and is expected to continue improving into theforeseeable future.Among many important factors contributing to the stabledevelopment <strong>of</strong> bilateral ties, the ethnic composition <strong>of</strong> Malaysiansociety is one that influences their bilateral engagement in manyareas. According to the 2010 census, 24.6% <strong>of</strong> Malaysia’s total populationis Chinese. 2 Unlike in many other countries where Chinesediasporic communities account for only a relatively small proportion<strong>of</strong> the total population (Singapore is the only exception), thepercentage <strong>of</strong> ethnic Chinese in Malaysia is high and represents asizable minority.Politically, Beijing does not openly support the political organizations<strong>of</strong> Malaysian Chinese outside <strong>of</strong> the ruling United Ma-1 Kankan XieIntroduction1 Ministry <strong>of</strong> Foreign Affairs <strong>of</strong> the PRC, Zhongguo Tong Malaixiya De Guanxi(China-Malaysia Relations), updated on 8/9/2011, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/chn/gxh/cgb/zcgmzysx/yz/1206_20/1206x1/t5702.htm (accessed 11/5/2012)2 Department <strong>of</strong> Statistics, Malaysia, Population and Housing Census, Malaysia2010, http://www.statistics.gov.my/portal/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1215&Itemid=89&lang=en,(accessed 10/26/2012)Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 2

lays National Organization (UMNO). In fact, the Communist Party<strong>of</strong> China (CPC) maintains close contact with both the UMNO andthe Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), the UMNO’s most importantally in domestic political campaigns and the largest Chinesepolitical party in Malaysia. Economically, Malaysian Chinesehave played critical roles in promoting bilateral trade and stimulatinginvestment both into and from China. Especially during theearly days <strong>of</strong> China’s reforms and opening up, Malaysian Chinesebusinessmen were among the first investors from overseas Chinesecommunities who first entered the still largely undevelopedChinese market. For obvious reasons, cultural affinities have to begiven serious consideration in explaining this quick embrace. TraditionalChinese culture has been well preserved in Malaysian Chinesesociety. Chinese language and Chinese education, althoughexperiencing various hardships, have survived decades <strong>of</strong> politicalstruggles. Such cultural linkages have not only played importantroles in maintaining Malaysian Chinese identity, but they also significantlycontributed to the development <strong>of</strong> China-Malaysia relationshipby facilitating channels <strong>of</strong> communication through personaland group connections.Ethnicity is always a central issue in Malaysian domesticpolitics. As early as the colonial era, ethnic tensions emerged dueto imbalances between the political and economic strength <strong>of</strong> differentethnic groups. After the Second World War, the introduction<strong>of</strong> the Emergency Regulation against the insurgency <strong>of</strong> the MalayanCommunist Party (MCP)—a predominantly Chinese leftwing politicalparty—greatly deepened existing racial tension. For a longperiod <strong>of</strong> time, China had openly supported the outlawed MCP infighting the guerrilla war against the Malay-dominated Malayan/Malaysian government. On 13 May 1969, a severe riot broke outin Kuala Lumpur, in which 196 people died because <strong>of</strong> interracialviolence. This incident further exacerbated the conflicts betweenMalays and Chinese. As a result, the Malaysian government adoptedmore stringent affirmative action policies in order to ease racialtension. 3 In 1974, with the establishment <strong>of</strong> diplomatic relations3 “Preparing for a Pogrom”, Time, 18 July 1969. Retrieved 14 May 2007.http://web.archive.org/web/20071116082658/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,901058-1,00.html(accessed 2/28/<strong>2013</strong>)between the two countries, Beijing severed its connections withthe MCP and China-Malaysia relations were normalized. Due tothis significant shift occurring after 1974, the ways in which ethnicityinfluences China-Malaysia relations will focus only on thepost-1974 era.Ostensibly, much inter-governmental engagement in multilateraldialogues has very little to do with issues related to ethnicity.But I believe the evidence shows that ethnicity does affect Malaysia’sforeign policy towards China. Specifically, in order to protectChinese interests domestically while reducing its dependence onethnic Chinese for dealing with China issues, the Malay-controlledMalaysian government has actively adopted implicitly pro-Chinapolicies, both bilaterally and multilaterally.To elaborate on these points, I will first discuss how ethnicitybecame a central issue in Malaysian society and how the Chinesediaspora fits into the Malaysian domestic political climate ingeneral. In the third section, I will discuss Malaysian perceptions<strong>of</strong> China based on a survey I conducted in 2009. Following this, Iwill underscore the mismatch between Malaysian Chinese’s heavyinvestment in China and their limited roles in domestic politics,which on one hand allows them to economically benefit from closeChina-Malaysia ties, but on the other hand, marginalizes this groupin inter-governmental dialogues. Finally, I will discuss how culturalissues affect China-Malaysia relations by examining the cases <strong>of</strong> thenewly founded Confucius <strong>Institute</strong> at the University <strong>of</strong> Malaya andMalaysia’s government fellowship program for students studyingin China.Ethnicity and Malaysian Domestic PoliticsDirectly influenced by British colonial rule that segregatedpeople along ethnic lines, Malay and its successor state Malaysia,since the colonial era has been described as a plural society parexcellence. Bumiputera is a politically constructed category, whichmeans “indigenous people,” literally a “son <strong>of</strong> soil.” It includes both3 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 4

the Malays and other indigenous peoples <strong>of</strong> Malaysia. 4 Throughthis categorization, Bumiputera has become the dominant majority<strong>of</strong> the country to the exclusion <strong>of</strong> ethnic Chinese and Indians.As <strong>of</strong> 2010, bumiputera accounted for 67.4% <strong>of</strong> the country’s totalpopulation, followed by Chinese at 24.6%, Indian (7.3%) and others(0.7%). 5As I have mentioned previously, the Chinese represent thesecond largest ethnic group in Malaysia with a population <strong>of</strong> nearlyseven million, 6 and their presence is significant by any measure.With a handful <strong>of</strong> active forces representing their communal interests,ethnic Chinese have played indispensible roles in the Malaysianpolitical arena. On the other hand, Malaysian politics is stillpredominantly ethnic-based and largely Malay-dominated.The Barisan Nasional (BN), along with its predecessor, theAlliance—largely comprised <strong>of</strong> ethnic-based political parties suchas the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), the MalaysianChinese Association (MCA) and the Malaysian Indian Congress(MIC)—has been the only ruling party coalition since the country’sindependence. 7 While ostensibly functioning as a multi-ethnic politicalparty coalition, the BN has been predominantly controlledby UMNO. Over the past five decades, the country’s prime ministersand the heads <strong>of</strong> the key ministries have always been members(Malays) <strong>of</strong> UMNO. Despite an <strong>of</strong>ficial consensus <strong>of</strong> pursuingracial harmony, to a large extent, each constituent party <strong>of</strong> the BNprimarily works in accordance with their respective ethnic interestsin hope <strong>of</strong> securing and maximizing votes from their own community.In fact, the origin <strong>of</strong> Malaysia’s communal politics can be4 According to the 2004 CIA World Factbook, Malays account for 50.4% <strong>of</strong> thetotal population, followed by Chinese 23.7%, indigenous 11%, Indian 7.1% and others7.8%. Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/my.html (accessed 10/24/2012).5 Department <strong>of</strong> Statistics, Malaysia, Population and Housing Census, Malaysia2010, http://www.statistics.gov.my/portal/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1215&Itemid=89&lang=en,(accessed 10/26/2012)6 ibid.7 The Barisan Nasional (also historically known as National Front) was formedin 1973 as the successor to the Alliance. Besides UMNO, MCA and MIC, participants <strong>of</strong>the BN also include other constituent parties such as Malaysian People’s MovementParty (GERAKAN) and People’s Progressive Party (PPP).traced back much earlier when Malayan/Malaysian people werefighting for independence. Although there was a wide range <strong>of</strong> politicaloptions advocated by different interest groups, the centralissues were always concentrated within the debate between twomajor camps: the bumiputera, who advocated the revival <strong>of</strong> Malaysovereignty as it existed in the pre-colonial era, and the non-Malayimmigrants, who struggled for equal rights and permanent citizenshipwithin the new country. In many Malay extremists’ view,“immigrants formed an inextricable part <strong>of</strong> the colonization process”and thus, the realization <strong>of</strong> the decolonization must be conductedwith an emphasis on the fact that “the land belongs to theMalays.” 8 In contrast, the Chinese and Indians were particularlyanxious to end colonization through popular sovereignty, includingthe participation <strong>of</strong> immigrants by granting them rights equalto the indigenous. As Muhammad Ikmal Said argued, “(The Malay’sspecial position or equal rights) is an open question and is an object<strong>of</strong> struggle. Such a struggle, <strong>of</strong> course, would not occur if theimmigrant communities in question are small, as they could be accommodated,that is, ‘controlled’, easily. On the other hand, if theyform a large proportion <strong>of</strong> the population, an economically strongermajority as in the Malayan case, the implications are very different.”9 In this sense, each ethnic group was big enough to contestthe others, but no single group had the absolute strength necessaryto take the lead without making compromises. This fact also ensuredthat almost all political issues in Malaysia are approached ascommunal struggles, or at least in most circumstances, communalinterests must be taken into account as a primary consideration.As <strong>of</strong> 1961, there were 7.19 million people living in Malaya,3.57 million <strong>of</strong> whom were Malays and were accounted the majority<strong>of</strong> the population; whereas within a Chinese population <strong>of</strong>2.63 million, only 880,000 had citizenship. 10 Despite the economicadvantages the ethnic Chinese enjoyed, they were politically un-8 Kahn, Joel S., and Francis Kok-Wah Loh, 1992, Fragmented vision: culture andpolitics in contemporary Malaysia. Honolulu, HI: University <strong>of</strong> Hawaii Press. P2619 ibid. P276.10 Sabah and Sarawak were not incorporated into Malaysia until 1963. BarisanSocialis Malaysia, “Malaixiya De Yiyi He Qiantu 马 来 西 亚 的 意 义 和 前 途 (The Meaningand Prospect <strong>of</strong> Malaysia: Lim Kcan Siew’s Speech in Johor),” Huo Yan Bao (Nyala), KualaLumpur: She Zhen, Vol. 3, Issue 10, May, 1963.5 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 6

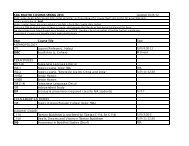

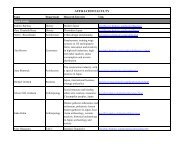

derprivileged due to a lack <strong>of</strong> eligible voters when the country’sindependence was achieved. By working closely with the dominantUMNO, the MCA successfully helped the vast majority <strong>of</strong> ethnicChinese obtain citizenship and secured its own position withinthe ruling party coalition. In exchange, however, the special right<strong>of</strong> bumiputera became legally acknowledged in the country’s constitution.11In the following decades, the UMNO-dominated federal governmentimplemented a series <strong>of</strong> policies that favored bumiputera,not only in hope <strong>of</strong> narrowing the economic gap between ethnicMalays and Chinese, but also to create a large and politically powerfulMalay middle class that would continuously support the UM-NO’s rule. In 1970, the New Economic Policy (NEP) was <strong>of</strong>ficiallyimplemented by the Mahathir administration in order to ease thetension provoked by the May 13 Incident <strong>of</strong> 1969, the most notoriousinterracial riot in the country’s history. Based on Article 153<strong>of</strong> the Constitution, the NEP specified the special rights enjoyed bybumiputera, including subsidies for real estate purchases, quotasfor public equity shares, and general subsidies to bumiputera businesses.As a result, ethnic Malays (elites in particular) became thelargest beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> such policies. The Chinese community, bycontrast, although not always content with the compromises theMCA made with the UMNO, usually had no better alternative thanrelying on this kind <strong>of</strong> political arrangement in order to make theirvoices heard. While primarily focused on the interests <strong>of</strong> the Malaycommunity, the UMNO also must help the MCA take care <strong>of</strong> Chineseinterests, and thus secure Chinese votes for the BN. Although sucha political structure has a very limited effect on alleviating tensionsbetween different ethnic groups domestically, it is helpful in maintaininga generally peaceful and stable environment in plural societieslike Malaysia.11 Also refers to “Ketuanan Melayu”, which is commonly translated as MalaySpecial Position, Malay Special Right, Malay Privilege, Malay Supremacy, etc., which wasrecognized by Article 153 <strong>of</strong> the Malaysian Constitution: “It shall be the responsibility<strong>of</strong> the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (the head <strong>of</strong> state <strong>of</strong> Malaysia) to safeguard the specialposition <strong>of</strong> the Malays and natives <strong>of</strong> any <strong>of</strong> the States <strong>of</strong> Sabah and Sarawak and thelegitimate interests <strong>of</strong> other communities in accordance with the provisions <strong>of</strong> thisArticle.”Malaysian Perceptions <strong>of</strong> ChinaBoth the Malaysian Chinese community and the Malaysiangovernment have played very important roles in improving theChina-Malaysia relationship, but their respective incentives arequite different. Beyond economic considerations, I believe that ethnicChinese in Malaysia have favorable perceptions <strong>of</strong> China largelydue to ethno-racial connections. In contrast, for the UMNO-controlledMalaysian government, in light <strong>of</strong> its major concern withmaintaining the status quo in Malaysian domestic politics, it seeksto make the Chinese community happy by maintaining friendlyties with China.To test this hypothesis, I conducted a survey <strong>of</strong> Malaysianperceptions <strong>of</strong> China in 2008. I collected data from 131 participantsfrom both Chinese and non-Chinese communities in Malaysiaand investigated their perceptions from three different angles,namely “China and Chinese,” “China-Malaysia Relationship,” and“Culture and Communication” (Table 1).Table 1Responses Frequency PercentageEthnicity Chinese 63 48.1%Non-Chinese 68 51.9%Age 15-24 105 80.2%24+ 26 19.8%Gender Male 44 33.6%Female 87 66.4%Student 102 77.9%OccupationBusinessmen 8 6.1%Staff 14 10.7%Farmer 5 3.8%Worker 2 1.5%7 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 8

EducationSecondary 6 4.6%Diploma 17 13.0%Bachelor 105 80.2%Post-graduate 3 2.3%Regardless <strong>of</strong> ethnic background, the majority <strong>of</strong> respondentsexpressed positive views <strong>of</strong> China’s national image (71%)and China’s efforts in dealing with global and regional issues(69.2%), reflecting Malaysian people’s generally positive impressions<strong>of</strong> China. The differences between ethnic groups are not statisticallysignificant (Table 2 and 3).Table 2How do you view China’s national image?Ethnic Group Responses PercentagePositive 77.9%Non-Chinese Negative 5.9%Neutral 16.2%Positive 63.5%Chinese Negative 8%Neutral 28.5%Table 3How do you view China’s efforts in dealing with global and regionalissues?Ethnic Group Responses PercentagePositive 75%Non-Chinese Negative 14.7%Neutral 10.3%Positive 62.9%Chinese Negative 16.1%Neutral 21%On other issues, however, there were huge divergences betweenethnic Chinese respondents and their non-Chinese counterparts:Table 4Which one <strong>of</strong> following countries is Malaysia’s most importantpartner?Ethnic Group Name <strong>of</strong> Country PercentageJapan 35.80%Non-Chinese China 31.30%The United States 20.90%Others 11.90%China 60.30%ChineseThe United States 23.80%Japan 11.10%Others 4.80%In this survey, I asked the participants to answer the question:which country is Malaysia’s most important partner, and listed“The United States,” “Japan,” “China” and “Others” as options.The Chinese respondents demonstrated a significant preferencefor China, with 60.3% <strong>of</strong> them selecting China as Malaysia’s “mostimportant partner.” In comparison, non-Chinese respondents didnot show any particular preference for any single country. Amongthree options, Japan ranked first, accounting for 35.8%, while Chinaand the US had slightly smaller proportions, namely 31.3% and20.9% (Table 4).Table 5Free trade between China and Malaysia will damage Malaysia’s interests.Ethnic Group Responses PercentageAgree 82.10%Non-Chinese Disagree 14.90%Do not Know 3%9 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 10

ChineseAgree 15.90%Disagree 73%Do not Know 11.10%As high as 82.1% percent <strong>of</strong> the non-Chinese respondentsbelieve that China-Malaysia free trade will damage Malaysia’s interests,whereas only 15.9% <strong>of</strong> Chinese respondents shared thesame concern (Table 5).In general, the development <strong>of</strong> economic collaboration hasdemonstrated strong momentum in recent years. China-Malaysiabilateral trade has been growing by double digits annually sincethe end <strong>of</strong> the Cold War. By the year 2002, Malaysia surpassed Singaporeto become China’s primary international trading partneramong ASEAN countries. As mentioned earlier, bilateral trade totaled$74.2 billion USD in 2011. 12 Significantly, Malaysia has longbeen running a bilateral trade surplus with China, making clearthat its economic position is by no means that <strong>of</strong> inferior partner.Furthermore, it is unsurprising that Malaysian Chinesedemonstrate greater satisfaction towards the bilateral economicrelationship due to close and frequent China/Malaysian-Chineseinteraction. While being the biggest beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> bilateral trade,the Malaysian Chinese also act as investors who contribute mostsignificantly to the bilateral collaboration. It is hard to find an accuratepercentage <strong>of</strong> their share <strong>of</strong> investment in Malaysia’s overallinvestment to China, 13 but Malaysian Chinese investors have surelyplayed major roles: As <strong>of</strong> 2009, Malaysian Chinese were running4,189 investment projects in China, which translates into a total <strong>of</strong>$4.53 billion USD Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). 14Table 6How do you feel about China’s foreign policy towards Malaysia?Ethnic Group Items PercentageSatisfied 25.40%Non-Chinese Dissatisfied 64.20%Do not Know 10.40%Satisfied 91.90%ChineseDissatisfied 6.40%Do not Know 1.70%Similarly, the overwhelming majority <strong>of</strong> ethnic Chinese respondentsfeel satisfied with China’s current policies towards Malaysia.Among the non-Chinese, however, 64.2% expressed dissatisfaction(Table 6).In general, both ethnic Chinese and non-ethnic Chinesehold positive views <strong>of</strong> China’s national image and its role in dealingwith regional and global issues. However, the survey also demonstratedthat China was more positively perceived among MalaysianChinese, who had good impressions <strong>of</strong> China regardless <strong>of</strong> whetheror not they had visited the country personally. Contrarily, China’simage needs improving among Malaysia’s non-Chinese citizens, asthese respondents expressed mostly negative feelings about theircountry’s current relationship with China. For the Malaysian government,it believes that maintaining a good relationship with Chinais a helpful strategy for taking care <strong>of</strong> the domestic interests <strong>of</strong>ethnic Chinese.12 Ministry <strong>of</strong> Foreign Affairs <strong>of</strong> the PRC, Zhongguo Tong Malaixiya De Guanxi(China-Malaysia Relations), updated on 8/9/2011, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/chn/gxh/cgb/zcgmzysx/yz/1206_20/1206x1/t5702.htm (accessed 11/5/2012)13 According to the data released by the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Foreign Affairs <strong>of</strong> the PRC,Malaysia’s FDI to China reached 5.6 billion US dollars in 2009.14 Zheng Da, Direct Investment in China from Chinese Malaysian Businessmensince the Reform and Opening up,P85-92 Mar. ,2009 Vol.16 No.2 Contemporary China History <strong>Studies</strong>The Dilemma <strong>of</strong> Being Malaysian ChineseAt the risk <strong>of</strong> oversimplifying, Malaysian Chinese occupyeconomically advantageous, but politically underprivileged, positionswithin Malaysian society. Rich ethnic Chinese businessmenrely heavily on Malay elites in securing their economic interests.11 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 12

Similarly, Chinese business tycoons’ strong financial support iscritical to the ruling Malay upper class. This situation has formeda typical patronage system, in which the powerful and the wealthyexchange resources effectively at the top, in spite <strong>of</strong> racial segregationon the lower rungs <strong>of</strong> society.In Malaysia, class divisions are systematically manipulatedwithin prevailing ethnic-based communal politics. Voices <strong>of</strong> thelower class are ignored or intentionally superseded by discourses<strong>of</strong> racial inequalities. The UMNO and the MCA, both largely representingthe elites in their respective ethnic groups, <strong>of</strong>ten use requestsfrom the lower classes as bargaining leverage against oppositionparties. To fully take advantage <strong>of</strong> ethnic Chinese citizens’favorable perceptions <strong>of</strong> China, both the UMNO and the MCA haveeagerly developed a close relationship with Beijing, as a way toshow their commitment and capability to take care <strong>of</strong> ethnic Chineseinterests in Malaysia.One <strong>of</strong> China’s most consistent policies towards Malaysiasince the establishment <strong>of</strong> diplomatic relations has been themaintenance <strong>of</strong> friendly ties with both the UMNO and the MCA.According to the records <strong>of</strong> the International Department, CentralCommittee <strong>of</strong> the CPC, in the past ten years the two sides have exchangedhigh-level delegations on an annual basis, without the involvement<strong>of</strong> the Malaysian opposition parties, regardless <strong>of</strong> ethniccomposition. 15Of course, it is also worth noting that the Malaysian Chinesewho have been making investments in China are <strong>of</strong> the same group<strong>of</strong> people who rely the most on the domestic patronage system. 16During the early years <strong>of</strong> China’s “Reform and Opening Up” policies,“overseas Chinese” was no doubt a very lucrative identity. On the15 International Department, Central Commitment <strong>of</strong> CPC, Foreign Affairs <strong>of</strong> theCPC, http://www.idcpc.org.cn/dongtai/index.htm (accessed 20 November 2012)16 By the mid-1990s, almost all the major Malaysian Chinese enterprises hadinvested in China, include Robert Kuok Hock Nien’s Kuok Brothers Sdn Bhd, WilliamCheng Heng Jem’s Lion Group, Lim Goh Tong’s Genting Group, Vincent Tan’s BerjayaCorporation Berhad, etc. Zheng Da, “Shixi Malaixiya Huashang Dui Hua Touzi De Fazhan,Wenti Yu Duice 试 析 马 来 西 亚 华 商 对 华 投 资 的 发 展 、 问 题 与 对 策 (Malaysian Chinese’sInvestment in China: Development, Problems and Policies),” Southeast <strong>Asian</strong> Affairs, No.32009 No. 139. Also see Gomez, Edmund Terence, and Jomo K. S. 1997. Malaysia’s PoliticalEconomy: Politics, Patronage, and Pr<strong>of</strong>its. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.one hand, people in China were eager to access the resources theMalaysian Chinese had in hand: capital, technology, and access t<strong>of</strong>oreign markets and overseas networks. On the other hand, beingethnically Chinese meant they could get things done easily in Chinaby using their Chinese networks when investors elsewhere werestill suspicious <strong>of</strong> China’s prospects. Being politically vulnerableand dependent, it was believed that the ethnic Chinese in Malaysia(as in other politically unstable countries) had stronger incentivesto put their eggs in other baskets. Afraid <strong>of</strong> losing their mostimportant financial resources, the Malay-dominated governmentalso became more generous in <strong>of</strong>fering pr<strong>of</strong>itable deals to thesewealthy Chinese businessmen as long as they remained active inthe domestic patron-client relationship.Despite knowing that it is very dangerous to let a powerfulcountry like China intervene in its domestic politics by forgingclose ties with the Malaysian Chinese, visionary Malay leaders decidedto take the initiative to engage Beijing directly by refusingto allow Malaysian Chinese to act as middlemen, and by keepingthem out <strong>of</strong> state-to-state interactions. The Malaysian governmenthas actively adopted an implicitly pro-China policy in both bilateraland multilateral dialogues. In fact, Malaysia is not only the firstASEAN country that established diplomatic relations with China,but also the first country that initiated the China-ASEAN Dialogueand hosted the China-ASEAN Summit. 17 At the regional level, Malaysiahas also been playing an important role in pushing forwardmultilateral cooperation between ASEAN and China as well as otherplayers from across the Pacific. Within the framework <strong>of</strong> regionalinstitutions such as ASEAN Plus Three, the Asia Cooperation Dialogue(ACD), and the <strong>East</strong> <strong>Asian</strong> Summit (EAS), China and Malaysiahave been working quite closely with each other. 18 Nonetheless,both China and Malaysia claim overlapping territorial waters withinthe South China Sea. But unlike Vietnam and the Philippines, the17 Xinhua News Agency, “Xi Jinping Huijian Malaixiya Fuzongli Maoxiding (XiJinping Met Muhyiddin Yassin, the Deputy Prime Minister <strong>of</strong> Malaysia)”, 21 September2012, (http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2012-09/21/c_123747237_2.htm) (Accessed2/24/<strong>2013</strong>)18 “Joint Communique Between the People’s Republic <strong>of</strong> China and Malaysia”,30 May 2004, People’s Daily, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200405/30/eng20040530_144795.html (accessed 2/20/<strong>2013</strong>)13 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 14

tension between Malaysia and China has rarely escalated. Armedconflict between the two countries has never occurred since theestablishment <strong>of</strong> diplomatic relations. 19 In dealing with territorialdisputes, both sides have agreed to follow the United NationsConvention on the Law <strong>of</strong> the Sea (UNCLOS), the Declaration onthe Conduct <strong>of</strong> Parties in the South China Sea, and the principle<strong>of</strong> “shelving disputes and seeking joint development.” 20 The ethnicChinese in Malaysia usually do not play any substantial role in suchinter-governmental interactions.How Chinese Language Education MattersOther than the general improvement in terms <strong>of</strong> politicalengagement and economic cooperation, the close China-Malaysiarelationship has boosted a high volume <strong>of</strong> cultural exchange betweenthe two countries. Due to the sharp imbalance <strong>of</strong> powerbetween the two countries, China’s cultural influence on Malaysiais far stronger than vice versa, is similar to the situation faced byother Southeast <strong>Asian</strong> countries. In addition, because <strong>of</strong> the largepercentage <strong>of</strong> ethnic Chinese, Malaysian society is not only moreaccommodating <strong>of</strong> Chinese culture, but there is also high demandto develop it locally.In societies where the Chinese presence is not significant,“Chinese culture” usually functions as a medium to showcase China’simage. In Malaysia, however, vaguely defined “Chinese culture”has multiple layers <strong>of</strong> meaning. First, it is an integral part <strong>of</strong> Malaysianculture itself, on which the identity <strong>of</strong> the Malaysian nationhas been politically constructed. Therefore, being recognized as an19 “Review: Disputes in the region”, Global Times, http://www.globaltimes.cn/SPECIALCOVERAGE/SouthChinaSeaConflict.aspx (accessed 2/17/<strong>2013</strong>)Also see “TIMELINE: The roots and present status <strong>of</strong> the WPS disputes”, The ManilaTimes, 02 September 2012, http://www.manilatimes.net/index.php/special-report/30222-timeline-the-roots-and-present-status-<strong>of</strong>-the-wps-disputes(accessed2/17/<strong>2013</strong>), “Timeline: Disputes in the South China Sea,” The Washington Post, 8 June2012, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/special/south-china-sea-timeline/index.html(accessed 2/18/<strong>2013</strong>)20 Deng Xiaoping, Speech at the Joint Press Conference <strong>of</strong> the State Visit to Japan,“Ge Zhi Zheng Yi, Gong Tong Kai Fa”, http://www.mfa.gov.cn/chn/gxh/xsb/wjzs/t8958.htm (accessed 12/05/2012)indispensable pillar in Malaysia’s plural society, Chinese cultureplays an important role in maintaining racial harmony and mutualrespect amongst different ethnic groups. Secondly, Chinese cultureis extremely important for the Chinese community in Malaysia.More specifically, it is both a powerful weapon that ethnic Chinesewield in domestic political struggles against the non-Chinese dominantpowers, as well as representing an ultimate goal that they intendto achieve, namely preserving their cultural identity. Althoughless explicit than these first two layers, a third layer is equally important:Chinese culture (Indian culture is similar in this case) isconstantly manipulated as a label that reflects the “foreignness” <strong>of</strong>the ethnic Chinese in Malaysia, which distinguishes them from thepolitically more privileged “local” and “indigenous” bumiputera.Consequently, while preserving their cultural identity by keepingthis “foreignness” and “otherness,”ethnic Chinese have preventedthemselves from accessing political resources that exclusively belongto the bumiputera.Therefore, the term “Chinese culture” is very ambiguous inMalaysia, conveying the meaning <strong>of</strong> both Chinese culture from Chinaand the culture <strong>of</strong> Malaysian Chinese themselves. Despite thefact that there are many differences between the two, they are alsoclosely connected to one another. Under the banner <strong>of</strong> preservingcultural identity, ethnic Chinese in Malaysia engage themselvesactively in cultural exchanges with China, including activities suchas ancestor worship, education cooperation, and joint festival celebrations.In respect to culture, the Chinese community benefitsmore from the close China-Malaysia bilateral relationship thanother ethnic groups.As the guardian <strong>of</strong> both the interests <strong>of</strong> the state and moreimportantly, the bumiputera community, the UMNO-controlledgovernment <strong>of</strong>ten plays seemingly contradictory roles in promoting—andsimultaneously curbing—the development <strong>of</strong> Chineseculture. As previously mentioned, the Malaysian government hasimplemented a series <strong>of</strong> economic policies that favor the bumiputerain terms <strong>of</strong> subsidies for real estate purchases, quotas for publicequity shares, and land ownership, etc. In fact, the government’sfavorable treatment <strong>of</strong> the bumiputera has gone far beyond therealm <strong>of</strong> purely economic interests. In the field <strong>of</strong> education, for in-15 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 16

stance, there are constant controversies amongst different ethniccommunities related to what the ethnic Chinese see as educationaldiscrimination.In Malaysia, there are basically two types <strong>of</strong> public elementaryschools. One is the Malay-medium national schools whereMalay (Bahasa Melayu) and English are the recognized languages<strong>of</strong> instruction. 21 The other type is the national-type schools whereethnic languages such as Chinese and Tamil are taught, while Malayand English courses remain compulsory. 22 Although ethnicChinese enjoy the freedom to send their children to either type <strong>of</strong>school at the primary level, students have few options but to attendMalay-medium high schools so that they can further their studiesat the country’s public universities. 23 Otherwise, they may chooseto attend private Chinese-medium schools outside <strong>of</strong> the publiceducation system, though the graduates <strong>of</strong> these schools can onlygo abroad for higher education and have absolutely no chance <strong>of</strong>enrolling in domestic public universities. Such education policiesresult from the 1956 Razak Report, in which the Malaysian governmentestablished the goal <strong>of</strong> making Malay the dominant medium<strong>of</strong> instruction by assimilating Chinese and English national-typeschools into the Malay-medium national school system. 24 Throughvarious types <strong>of</strong> political campaigns and fund raising projects, theMalaysian Chinese have exerted every effort to protect their owneducation system. To this day, however, the government does notrecognize the Chinese-medium independent schools. Due to thefavorable treatment <strong>of</strong> bumiputera, it is also far more difficult forChinese and Indian students who attend Malay-medium nationalschools to get in to public universities, not to mention the paucity<strong>of</strong> financial aid available to non-bumiputera students.One <strong>of</strong> the consequences <strong>of</strong> such education policies is atrend among ethnic Chinese students to study abroad. Traditionally,Singapore and Taiwan have been two major destinations for Ma-21 Sekolah Kebangsaan.22 Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan23 Chow Kum Hor, Battle to save Malaysia’s Chinese dropouts, Asia One, TheStraits Times, 31 Jan 2008 http://www.asiaone.com/News/Education/Story/A1Story20080130-47357.html(Accessed 11/29/2012)24 ibid.laysian students <strong>of</strong> Chinese background, not only because <strong>of</strong> theirgeographical proximity and their close linguistic and ethno-racialties with the ethnic Chinese in Malaysia, but also due to their ownrespective policies <strong>of</strong> attracting ethnic Chinese students from overseas.25 Boosted by the rapid development <strong>of</strong> the China-Malaysia bilateralrelationship in recent years, however, there is an increasingnumber <strong>of</strong> Malaysian Chinese students who choose to study in China,owing to the fact that China has a wider range <strong>of</strong> schools at arelatively lower cost. As <strong>of</strong> 2011, there were approximately 4,000Malaysian students studying in China. 26 Unsurprisingly, these studentsare predominantly self-financed ethnic Chinese, althoughthe exact number is unknown.In the name <strong>of</strong> continuously promoting the development <strong>of</strong>the bilateral relationship, in 2007 the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education <strong>of</strong> Malaysia(KPM) launched a government scholarship program to trainMalaysian Mandarin teachers. Selecting students from nationalhigh schools across the country, the KPM has since sent out fivebatches <strong>of</strong> students to Beijing Foreign <strong>Studies</strong> University (BFSU)to pursue bachelor degrees in teaching Mandarin as a second language.27 Following the KPM program, the Majlis Amanah Rakyat(MARA), a government-run bumiputera development agency, hasalso signed an agreement with BFSU to train Mandarin teachers. As<strong>of</strong> 2012, there have been 175 Malaysian students studying at BFSUthrough these two programs. Like many other government educationprograms in Malaysia, the recipients <strong>of</strong> these two scholarshipsare predominantly Malay. According to an unpublished documentfrom BFSU, out <strong>of</strong> the 175 students, there are only two ethnic Chinese,one ethnic Indian, and three indigenous Kadazans. 28In addition to helping Malaysia train its non-ethnic Chinese25 Lim Mun Fah, More expensive to study in China than Taiwan, SinchewDaily, 22 July 2010, http://news.asiaone.com/News/Education/Story/A1Story20100722-228336.html(accessed 12/03/2012)26 Premier Wen Jiabao’s speech at the Malaysia-China Economic, Trade, andInvestment Cooperation Forum in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on 28 April 2011.27 Program Pendidikan Ijazah Bahasa Mandarin, Zhao Wanzhen, “Speech at theOpening Ceremony <strong>of</strong> the 2012 Malaysian Mandarin Teacher Training Program at BFSU”(unpublished document), September 2012.28 Beijing Foreign <strong>Studies</strong> University, “2012 nian 9 yue yingjie malaixiya jiaoyubu”(Welcoming the KPM Delegation in September 2012), (unpublished document), September201217 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 18

Mandarin teachers in China, Beijing is also expanding its own educationnetwork in Malaysia. As part <strong>of</strong> China’s global strategy inadvancing its “s<strong>of</strong>t power,” a Chinese government-sponsored network<strong>of</strong> educational organizations named the “Confucius <strong>Institute</strong>”has been established to teach Chinese language and promote Chineseculture worldwide. 29 In contrast to most countries where thename “Confucius” represents a school <strong>of</strong> philosophical thought, inMalaysia the word is closely associated with the religious beliefs<strong>of</strong> a certain fraction <strong>of</strong> the ethnic Chinese community in Malaysia,distinguished from ethnic Chinese Buddhists and Taoists. As a result,the Confucius <strong>Institute</strong> has experienced several unexpecteddifficulties in getting approval from the UMNO-controlled governmentto establish its branch in Malaysia, as many conservativeparty members were concerned that the institution would play arole in promoting the religion <strong>of</strong> a particular segment <strong>of</strong> ethnic Chinese.30 As a compromise, the first Confucius <strong>Institute</strong> in Malaysiahas changed its name into “Kong Zi <strong>Institute</strong> for the Teaching <strong>of</strong>Chinese Language” (KZIUM), to rid itself <strong>of</strong> the religious implications<strong>of</strong> “Confucianism.” 31More importantly, the “Kong Zi <strong>Institute</strong>” is specially tailoredto serve the non-Chinese community in Malaysia. Accordingto an unpublished document <strong>of</strong> the institute, 1104 students enrolledin its Chinese language courses in the first year (2011) <strong>of</strong>operation. 32 Malays accounted for approximately 80% <strong>of</strong> the totalnumber, whereas the percentage <strong>of</strong> Chinese and Indian studentswas 15% and 5% respectively. 33 This situation is distinct from otherChinese language training institutions in Malaysia such as thenon-Chinese government-sponsored Global Hanyu & Culture Collegeand the Mandarin Journey Language Center run by MalaysianChinese, where ethnic Chinese account for the overwhelming ma-29 The Economist, China’s Confucius <strong>Institute</strong>s: Rectification <strong>of</strong> Statues, 20 Jan2011. http://www.economist.com/node/17969895 (accessed 12/05/2012)30 Zhao Wanzhen, interview by author, 12/05/2012. Zhao Wanzhen worked as alanguage lecturer at the KZIUM from 2011 to 2012.31 “Kong Zi” is the exact Chinese pinyin spelling <strong>of</strong> “Confucius”.32 Kong Zi <strong>Institute</strong> For the Teaching <strong>of</strong> Chinese Language at University <strong>of</strong>Malaya, “Ma Da Kong Yuan PPT” (Introduction to the KZIUM), (unpublished document),06/23/201233 ibid.jority <strong>of</strong> their respective student bodies.On top <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fering courses to the public, the KZIUM activelyengages in special language training programs for Malaysiangovernment employees by cooperating with the <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>of</strong> Diplomacy& Foreign Relations (IDFR), the National Defense University(UPNM) and the Royal Malaysia Police College (RMPC). 34 Directlyinfluenced by the ethnic composition <strong>of</strong> personnel in the Malaysiangovernment, most <strong>of</strong> the participants <strong>of</strong> these programs are Malays.For example, out <strong>of</strong> 184 IDFR students who registered for languagecourses, only two were ethnic Chinese and eight were ethnic Indians.Similarly, 54 out <strong>of</strong> 55 students from the RMPC were Malays. 35According to Zhao Wanzhen, a language lecturer who worked atthe KZIUM from 2011 to 2012, there is virtually no connection betweentheir institute and local ethnic Chinese organizations whatsoever.36ConclusionMalaysia’s domestic politics is highly ethnic-based. Due toimbalances <strong>of</strong> political and economic status between the bumiputeraand non-bumiputera communities in this plural society, differentethnic groups have engaged in constant struggles to securetheir respective communal interests. Although tensions betweendifferent ethnic groups are sometimes politically manipulated, ethnicityremains a central issue in the domestic politics <strong>of</strong> Malaysia.As the second largest ethnic group in Malaysia, the Chinesecommunity plays indispensable roles in the country’s political arena.Their resilient linguistic and ethno-racial ties with China havemeant that the engagement between China and Malaysia is not aconventional state-to-state relationship. The basic pattern <strong>of</strong> Malaysia’sdomestic politics has strongly influenced its foreign policytoward China. Due to the favorable perceptions <strong>of</strong> China amongMalaysian Chinese, the Malay-controlled government has been cautiousin developing its bilateral relationship with Beijing. It needs34 Maktab Polis Diraja Malaysia35 Zhao Wanzhen, interview by author, 12/05/2012.36 Ibid.19 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 20

to maintain and improve this relationship in order to satisfy theethnic Chinese, especially business tycoons who have made largeinvestments in China and play critical roles in its domestic patronagesystem. Conversely, it has to prevent Malaysian Chinese fromgetting too close to a powerful Beijing, consequently jeopardizingthe country’s own security. To do so, while taking the initiative toengage Beijing in both bilateral cooperation and multilateral dialogues,the Malaysian government has simultaneously marginalizedethnic Chinese Malaysians in intergovernmental interactions.The high volume <strong>of</strong> cultural exchanges between China andMalaysia should not be regarded as simply the combination <strong>of</strong> closegovernment-to-government engagement and increasingly developedpeople-to-people interactions. Rather, it is a very complexnetwork, in which the two governments and people with differentbackgrounds play distinct and variable roles. The ethnic Chinese inMalaysia rely heavily on the ethno-racial ties with China in orderto protect their cultural identity in their political struggles againstthe dominant Malay majority. The Malaysian government, by contrast,usually plays a contradictory role in both promoting andcurbing “Chinese culture.” Specifically, it restrains the development<strong>of</strong> Malaysian Chinese culture by prioritizing the interests <strong>of</strong> the bumiputeracommunity in most <strong>of</strong> its political agendas. At the sametime, however, it is also very active in improving bilateral ties withBeijing by promoting “Chinese culture from China” in its non-Chinesecommunities in order to encourage racial harmony among itsconstituent ethnic groups. In return, while benefiting tremendouslyfrom a momentum driven, in large part, by its close interactionwith ethnic Chinese in Malaysia, Beijing has tactically maintaineda good relationship with the Malay-controlled Malaysian governmentby acquiescing to their demand to respect the interests <strong>of</strong>the bumiputera, and by excluding ethnic Chinese Malaysians fromcertain sectors <strong>of</strong> inter-governmental cooperation.The basic pattern <strong>of</strong> Malaysia’s ethnic composition is unlikelyto change in the foreseeable future. Therefore, ethnicity willcontinue to play an important role in shaping the bilateral relationshipbetween China and Malaysia. This does not mean, however,that the current relationship is not subject to change. In fact, theUMNO-led Barisan National is facing an unprecedented challengein the upcoming election from the opposition party coalition PakatanRakyat, consisting <strong>of</strong> the self-proclaimed non-ethnic-basedPeople’s Justice Party, the Chinese-led Democratic Action Partyand the deeply conservative Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (Malays).Regardless <strong>of</strong> the election’s final results, it is widely believed thatthe country’s domestic politics may be undergoing a major paradigmshift away from a largely ethnic-based arrangement. If thishappens, it is unclear whether the China-Malaysia relationship willcontinue to follow its current trajectory.21 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 22

References“Joint Communique Between the People’s Republic <strong>of</strong> Chinaand Malaysia”, 30 May 2004, People’s Daily, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200405/30/eng20040530_144795.html(accessed2/20/<strong>2013</strong>).“Preparing for a Pogrom”, Time, 18 July 1969. Retrieved 14May 2007.http://web.archive.org/web/20071116082658/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,901058-1,00.html(accessed 2/28/<strong>2013</strong>).“Review: Disputes in the region”, Global Times, http://www.globaltimes.cn/SPECIALCOVERAGE/SouthChinaSeaConflict.aspx(accessed 2/17/<strong>2013</strong>).“Timeline: Disputes in the South China Sea,” The WashingtonPost, 8 June 2012, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/special/south-china-sea-timeline/index.html (accessed2/18/<strong>2013</strong>).“TIMELINE: The roots and present status <strong>of</strong> the WPS disputes”,The Manila Times, 02 September 2012, http://www.manilatimes.net/index.php/special-report/30222-timeline-the-rootsand-present-status-<strong>of</strong>-the-wps-disputes(accessed 2/17/<strong>2013</strong>).“Xi Jinping Huijian Malaixiya Fuzongli Maoxiding (Xi JinpingMet Muhyiddin Yassin, the Deputy Prime Minister <strong>of</strong> Malaysia)”,Xinhua News Agency, 21 September 2012, (http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2012-09/21/c_123747237_2.htm) (Accessed2/24/<strong>2013</strong>).Barisan Socialis Malaysia, “Malaixiya De Yiyi He Qiantu 马来 西 亚 的 意 义 和 前 途 (The Meaning and Prospect <strong>of</strong> Malaysia: LimKcan Siew’s Speech in Johor),” Huo Yan Bao (Nyala), Kuala Lumpur:She Zhen, Vol. 3, Issue 10, May, 1963.Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/my.html (accessed 10/24/2012).Chow Kum Hor, Battle to save Malaysia’s Chinese dropouts,Asia One, The Straits Times, 31 Jan 2008 http://www.asiaone.com/News/Education/Story/A1Story20080130-47357.html (Accessed11/29/2012)Deng Xiaoping, Speech at the Joint Press Conference <strong>of</strong> theState Visit to Japan, “Ge Zhi Zheng Yi, Gong Tong Kai Fa”, http://www.mfa.gov.cn/chn/gxh/xsb/wjzs/t8958.htm (accessed 12/05/2012)Department <strong>of</strong> Statistics, Malaysia, Population andHousing Census, Malaysia 2010, http://www.statistics.gov.my/portal/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1215&Itemid=89&lang=en,(accessed 11/7/2012).Gomez, Edmund Terence, and Jomo K. S. 1997. Malaysia’sPolitical Economy: Politics, Patronage, and Pr<strong>of</strong>its. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.International Department, Central Commitment <strong>of</strong> CPC,Foreign Affairs <strong>of</strong> the CPC, http://www.idcpc.org.cn/dongtai/index.htm(accessed 20 November 2012).Kahn, Joel S., and Francis Kok-Wah Loh, 1992, Fragmentedvision: culture and politics in contemporary Malaysia. Honolulu,HI: University <strong>of</strong> Hawaii Press.Lim Mun Fah, More expensive to study in China than Taiwan,Sinchew Daily, 22 July 2010, http://news.asiaone.com/News/Education/Story/A1Story20100722-228336.html (accessed12/03/2012).Ministry <strong>of</strong> Foreign Affairs <strong>of</strong> the PRC, Zhongguo TongMalaixiya De Guanxi (China-Malaysia Relations), updated on8/9/2011, http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/chn/gxh/cgb/zcgmzysx/yz/1206_20/1206x1/t5702.htm (accessed 11/5/2012).Premier Wen Jiabao’s speech at the Malaysia-China Economic,Trade, and Investment Cooperation Forum in Kuala Lumpur,Malaysia on 28 April 2011.The Economist, China’s Confucius <strong>Institute</strong>s: Rectification <strong>of</strong>Statues, 20 Jan 2011. http://www.economist.com/node/17969895(accessed 12/05/2012).Zheng Da, “Shixi Malaixiya Huashang Dui Hua Touzi DeFazhan, Wenti Yu Duice 试 析 马 来 西 亚 华 商 对 华 投 资 的 发 展 、 问 题与 对 策 (Malaysian Chinese’s Investment in China: Development,Problems and Policies),” Southeast <strong>Asian</strong> Affairs, No.3 2009 No.139.Zheng Da, Direct Investment in China from Chinese MalaysianBusinessmen since the Reform and Opening up, Contempo-23 Kankan Xie Ethnicity And China-Malaysia Relations 24

ary China History <strong>Studies</strong>, P85-92 Mar., 2009 Vol.16 No.2.Unpublished DocumentBeijing Foreign <strong>Studies</strong> University, “2012 nian 9 yue yingjiemalaixiya jiaoyubu” (Welcoming the KPM Delegation in September2012), (unpublished document), September 2012.Kong Zi <strong>Institute</strong> For the Teaching <strong>of</strong> Chinese Language atUniversity <strong>of</strong> Malaya, “Ma Da Kong Yuan PPT” (Introduction to theKZIUM), (unpublished document), 06/23/2012.Zhao Wanzhen, “Speech at the Opening Ceremony <strong>of</strong> the2012 Malaysian Mandarin Teacher Training Program at BFSU” (unpublisheddocument), September 2012.InterviewZhao Wanzhen, interview by author, 12/05/2012.Constructing “Culture”Mark PortilloAbstractDespite the vast amount <strong>of</strong> research surrounding Western photojournalist’srole in the Vietnam War, little is known about photography and its uses bythe Vietnamese communist leadership during and after the war. Western photojournalistsaimed to highlight the unnecessary suffering <strong>of</strong> the GI and the brutalviolence occurring overseas, but what were the Vietnamese aiming to achievewith their images? To answer this question, I conducted a comparative historicalanalysis <strong>of</strong> communist leadership relationships to modes <strong>of</strong> culture production,specifically photography. Through this comparative analysis I demonstrate howphotographs have served the nation’s Communist leadership by aiding in theconstruction <strong>of</strong> a cultural memory and consequently, a politicized identity. Thisresearch is part <strong>of</strong> a growing body <strong>of</strong> research on memory, culture production,and their role in politics. By utilizing photography and drawing attention to its importantrole in struggles for power, it is my hope that this research will contributeand promote future related projects.IntroductionHow can the culture <strong>of</strong> an entire country be constructed?The answer lies in cultural memory. In this essay I will discussmemory, what it means for a culture to remember, how that culturalmemory is constructed, produced, and for what purpose. I willlook specifically at the changing Vietnamese cultural memory beginningfrom the Vietnam War to the present. Through a comparativehistorical analysis <strong>of</strong> communist leadership relationships to25 Kankan Xie Constructing “Culture” 26

modes <strong>of</strong> culture production I will demonstrate how photographshave served to construct cultural memory. It is through this constructedcultural memory that a heroic Vietnamese national identityhas been constructed and exploited in Vietnam’s political sphereboth in the past as well as the present.It is important to understand that there is a definite tensionbetween the uses <strong>of</strong> the past as a legitimizing device, as a means<strong>of</strong> constructing community, as well as its repackaging as a marketablecommodity. 1 Thus, the struggle over the past is an aspect <strong>of</strong>control over the future. Photography in Vietnam serves to reflectthese tensions in the nation <strong>of</strong> Vietnam. The relationship betweenphotography and the nation had not been substantially developeduntil 1945 and not fully realized until the Vietnam War. 2 From theVietnam War to present day, photography has served as a socialmirror reflecting an image to the nation’s inhabitants. The “imagein the mirror” comes from memory, more specifically culturalmemory. This memory is constructed through re-writing the pastto reflect the interests <strong>of</strong> those in power. To understand how thisfeat is accomplished it is important to understand memory andmore importantly, memory’s relationship to identity.Cultural Memory and National IdentityMemory establishes life’s continuity; it gives meaning to thepresent, as each moment is constituted by the past. As the means bywhich we remember who we are, memory provides the very core<strong>of</strong> identity. 3 This understanding <strong>of</strong> memory can be extended to answerbigger questions <strong>of</strong> what it means for a nation to rememberand the importance <strong>of</strong> constructing cultural memory. A nation’smemory <strong>of</strong> what their culture is can <strong>of</strong>ten appear similar to that <strong>of</strong>an individual. Memory serves as a tool for an individual to shape1 Tai, Hue-Tam Ho. The Country <strong>of</strong> Memory: Remaking the past in Late SocialistVietnam. Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong> California, 2001.2 Lê, Phức, and Thành, Chi. Ảnh Việt Nam Thế Kỷ XX = Vietnamese Photographyin the 20th Century = La Photographie Du Vietnam Au 20e Siècle. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất BảnVăn Hoá Thông Tin, 2002.3 Sturken, Marita. Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, andthe Politics <strong>of</strong> Remembering. Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong> California, 1997.their identity and remember “who they are,” and in this way a collectivecultural memory serve to shape the identity <strong>of</strong> a nation. Thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> cultural memory is complex because it is boundto various political stakes and meanings. Cultural memory servesto both define culture and is the means by which its divisions andconflicting agendas are revealed. 4To define memory as culture is, in effect, to enter into a debateabout what that memory means because the cultural memoryprocess does not efface an individual, but rather involves the interaction<strong>of</strong> individuals in the creation <strong>of</strong> cultural meaning. 5 Culturalmemory is a field <strong>of</strong> cultural negotiation through which differentstories vie for a place in history. To summarize, the term “culturalmemory” is to be understood as a memory that is shared outsidethe avenues <strong>of</strong> formal historical discourse yet is entangled with culturalproducts and imbued with cultural meaning. 6 Cultural memoryis produced in various forms, such as memorials, public art, popularculture literature, commodities, and activism. Understandinghow individual memory leads to a collective cultural memory allowsfor the significance <strong>of</strong> cultural memory to be ascertained.Importance <strong>of</strong> Memory in PoliticsMemory is a political force. Foucault asserts that “sincememory is actually a very important factor in struggle, if one controlspeople’s memory, one controls their dynamism.” Culturalmemory draws its significance from the ability to serve as a core <strong>of</strong>identity for a nation and political force that a core identity carrieswith it. Identity is an important political tool because leaders useidentity to legitimize their questionable agendas in multiculturalcountries, to further undermine opposing voices, and to marginalizediffering opinions. The process whereby identities becomepoliticized as well as mobilized are in wars and their many differentrepresentational contexts (i.e. monuments, etc.), in order to4 Ibid.5 Ibid.6 Ibid27 Mark Portillo Constructing “Culture” 28

produce political resistance, social solidarity, and civic virtue. 7 InVietnam’s history there are many examples <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> these politicalevents as leaders have utilized a constructed identity to anchortheir legitimacy to power. With this being understood I draw attentionto the process by which a culture memory is produced.Production <strong>of</strong> Cultural MemoriesIn Destination Culture, Barbara Gimblett discusses how cultureis produced. Her focus is on heritage as the new mode <strong>of</strong> cultureproduction in the present and how it has recourse in the past.Gimblett emphasizes how:Heritage is not lost and found, stolen and reclaimed. Despite a discourse<strong>of</strong> conservation, preservation, restoration, reclamation, recovery,re-creation, recuperation, revitalization, and regeneration, heritageproduces something new in the present that has recourse to thepast. Such language suggests that heritage is there prior to its identification,evaluation, conservation, and celebration. By production, I donot mean that the result is not “authentic” or that it is wholly invented.Rather, I wish to underscore that heritage is not lost and found, stolenand reclaimed. It is a mode <strong>of</strong> cultural production in the present thathas recourse to the past.Gimblett’s analysis <strong>of</strong> culture production serves as a tool for understandingphotography in Vietnam.As Gimblett’s writings stress, culture is neither lost norfound. Culture is ubiquitous and takes on various forms. Vietnamis comprised <strong>of</strong> an ethnically diverse people, however the governmenthas promoted one cultural identity, namely the identity constructedby the Communist party. At no point in Vietnam’s historyhas a constructed culture been so clearly produced than <strong>of</strong> thatsurrounding the Vietnam War. This identity is remarkably visiblein the photography <strong>of</strong> the Vietnamese during this period, and iseven more identifiable when compared with that <strong>of</strong> the Americans.7 Tai, Hue-Tam Ho. The Country <strong>of</strong> Memory: Remaking the past in Late SocialistVietnam. Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong> California, 2001.Contrasting FocusesUnlike Westerners who were primarily in Vietnam on a “voluntarybasis and could walk away if they so desired, the freedom toleave their country and the war was not an option for Vietnamesephotographers.” 8 The war was at home for Vietnamese photographersand their contingence to the domestic suffering <strong>of</strong> war permeatedthe meanings and subjects that Vietnamese photographerschose to capture, as well as into the images that the National LiberationFront promoted. In addition, Vietnamese photojournalismwas not predicated on violence and disaster alone, but upon theplacement <strong>of</strong> suffering within a broader spectrum <strong>of</strong> wartime experiencesand subjectivities, and it thus produced a more extensiveand informative visual history. 9 As explained in Schwenkel’s writings,culture played a huge role in what was photographed by theVietnamese during the war.Unlike reporters working for the Western press, most <strong>of</strong> whomwere independent <strong>of</strong> the war effort and thus regarded as “objective”outside observers, Vietnamese correspondents were consideredcultural soldiers <strong>of</strong> the revolution, whose weapons consisted<strong>of</strong> pencils, paper, and in the case <strong>of</strong> photojournalists, cameras. Ininterviews and conversations, photographers stressed the importance<strong>of</strong> photography to serve the country, denounce the war tonational and international audiences, and transmit and propagateinformation from the front. But they also emphasized their multivalentroles as cultural producers immersed in the social worlds <strong>of</strong>the people who comprised their subject matter. They endeavoredto show the crimes, destruction, and techniques <strong>of</strong> war, as well asthe cooperation, compassion, and social interactions among soldiersand villagers.Despite the variety <strong>of</strong> cultural messages captured by Viet-8 Schwenkel, Christina. Exhibiting War, Reconciling Pasts: Photographic Representationand Transnational Commemoration in Contemporary Vietnam. Journal <strong>of</strong>Vietnamese <strong>Studies</strong> 3.1, 2008.9 Ibid29 Mark Portillo Constructing “Culture” 30

namese photographers, only those that shared the cultural wartimepurposes <strong>of</strong> the National Liberation Front were widely circulated.Constructed Cultural Memory during the WarThe communist cultural message is characterized by are-written past that reflected a heroic narrative and ultimately triumphantstruggle against foreign domination, while inscribing thefuture as a vision <strong>of</strong> communist utopia achieved through the inexorableworkings <strong>of</strong> History, Marxist style. 10 Images circulated typicallycaptured enthusiastic soldiers, crowds <strong>of</strong> joyous people (toconvey popular support), and moments <strong>of</strong> victory. These messagesare encapsulated in the subjects and circulations <strong>of</strong> what have nowbecome iconic photos taken by Vietnamese photographers. Themost widely circulated photo is that which captured the shootingdown <strong>of</strong> an American F-105D during a raid on Hanoi. Another famousphotograph is that <strong>of</strong> a young woman carrying a rifle whileescorting a captured American pilot. Another is <strong>of</strong> a group <strong>of</strong> youngsoldiers smiling and an image capturing Northern Vietnameseforces towering over enemy corpses to solidify an image victory.Constructed Cultural Memory <strong>of</strong> the War TodayToday the Vietnam War is portrayed in a different, but veryfamiliar way. Contrary to the graphically violent photographs thatin the United States narrate the history <strong>of</strong> the war as a moral andpolitical failure, images displayed in Vietnamese museums depictthe virtues, hopes, labors, and triumphs <strong>of</strong> the revolution to producea narrative <strong>of</strong> progressive and total victory. 11 Images typically10 Tai, Hue-Tam Ho. The Country <strong>of</strong> Memory: Remaking the past in Late SocialistVietnam. Berkeley: University <strong>of</strong> California, 2001.11 Schwenkel, Christina. Exhibiting War, Reconciling Pasts: Photographic Representationand Transnational Commemoration in Contemporary Vietnam. Journal <strong>of</strong>Vietnamese <strong>Studies</strong> 3.1, 2008.contain “themes <strong>of</strong> joy, play, enthusiasm and even love. Images inVietnamese museums regularly show acts <strong>of</strong> labor and preparationfor war, providing a visual testimony to Vietnam’s historical andheroic ‘spirit <strong>of</strong> resistance to foreign aggression in action.’ 12 Furthermore,Schwenkel emphasizes how these images re-inscribethe centrality <strong>of</strong> discourses <strong>of</strong> unity and solidarity to the war effort,as evident in photographs taken during or immediately after combatthat foreground action and victory rather than casualties. Evenwhen injured troops are present, the emphasis is on camaraderie(such as tending to their wounds) rather than on their pain andsuffering . 13Evidence <strong>of</strong> Constructed Cultural MemoryAs previously stated, American War photography served toconstruct a culture memory that starkly contrasts with that <strong>of</strong> theVietnamese. The memory is one <strong>of</strong> a moral and political failure. Famousphotographs that helped to sway American public opinionwere aimed at capturing the unnecessary suffering <strong>of</strong> the AmericanGI and the atrocities that occurred during the war. The Vietnamesegovernment has taken these famous photos from Western cultureand re-written their meanings to serve their interests. The Ministry<strong>of</strong> Culture takes this action because there are “political-ideologicalmotivations for utilizing photography ins<strong>of</strong>ar as the state regularlyinvokes memories <strong>of</strong> war through images to commemorate andkeep the spirit <strong>of</strong> the revolution alive, as well as to teach the youthabout the past, (so that) there is political interest in emphasizingvictorious achievements and collective acts <strong>of</strong> solidarity.” 14Gimblette’s process <strong>of</strong> cultural production and Schwenkel’snotes about the significance <strong>of</strong> utilizing photography as a politicaltool is exemplified by the book Vietnamese Photography in the20th Century. The book, released by Vietnam’s Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture,features over 2,000 photos that are “closely linked to Vietnam12 Ibid1314 Ibid31 Mark Portillo Constructing “Culture” 32

and its people through many historical ups and downs.” 15 Amongthe numerous images, the book contains famous photos taken byWestern photojournalists. The Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture has taken theseimages and has explicitly re-captioned them in order to promotethe Vietnamese government’s constructed cultural memory <strong>of</strong> thewar. 16Walter Cronkite wrote in LIFE, “correspondents and photographersin Vietnam could, accompany troops to wherever theycould hitch a ride, and there was no censorship . . . That system—or lack <strong>of</strong> one—kept the American public well informed <strong>of</strong> our soldiers’problems, their setbacks and their heroism.” Capturing imagesthat highlighted the factors Cronkite mentioned was a maingoal for American photojournalists. An example <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong>powerful imagery that came out <strong>of</strong> the Vietnam War is the photo“Reaching Out” taken by Larry Burrows. This iconic photo has beentaken by the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture and re-captioned with the message“US troops died at the battlefields in Central Vietnam”. Thiscaption demonstrates a stark contrast with the interpretation <strong>of</strong>the war <strong>of</strong>fered in the original LIFE caption that reads “a woundedMarine desperately trying to comfort a stricken comrade after afierce firefight.”Purposes <strong>of</strong> Constructed Cultural MemoryThe combination <strong>of</strong> the circulation <strong>of</strong> chosen images and their captioningby the Vietnamese government serves as a visual insightinto the strategies and workings <strong>of</strong> constructing the cultural memory<strong>of</strong> a people’s war. 17 Through a strategy <strong>of</strong> publicizing imagesthat capture citizens <strong>of</strong> different ages and genders participatingin the war effort, the government helped legitimize its claims towaging a “people’s war.” After the war, the re-captioning <strong>of</strong> famous15 Lê, Phức, and Thành, Chi. Ảnh Việt Nam Thế Kỷ XX = Vietnamese Photographyin the 20th Century = La Photographie Du Vietnam Au 20e Siècle. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất BảnVăn Hoá Thông Tin, 2002.16 Ibid17 Schwenkel, Christina. Exhibiting War, Reconciling Pasts: Photographic Representationand Transnational Commemoration in Contemporary Vietnam. Journal <strong>of</strong>Vietnamese <strong>Studies</strong> 3.1, 2008.photos helped the government hold on to this inherited right topower. The constructed historical narrative promotes the idea thatthe government in the past had fought and won the “people’s war,”and that the current government now continues to uphold its pastgoals and aspirations. The stake in maintaining this cultural memory<strong>of</strong> a “glorious war” lies in the power the memory has in legitimizingthe government. Legitimacy is the main concern for thecommunist government <strong>of</strong> Vietnam.The government’s concern with legitimacy manifests itselfin the severe curtailment <strong>of</strong> civil and political rights in the hope<strong>of</strong> maintaining the one-party system that is seen as essential forthe unity and prosperity <strong>of</strong> the country. 18 These limitations stemfrom general anxieties about state independence, territorial integrity,and social cohesion. 19 Vietnam extends this curtailment <strong>of</strong> civiland political rights to photographers and their photographs. Thetension between government anxieties and the photographer’sartistic expressions are encapsulated in the significant changes inculture production following the Doi Moi reform periods.The Doi Moi Reforms and Culture ProductionAfter political reunification in 1975 the Communist leadership<strong>of</strong> Vietnam decided to pursue a second five year plan whichaimed to integrate the North and South Vietnam economies as rapidlyas possible with the socialist transformation <strong>of</strong> Vietnamese societybeing the ultimate goal. 20 The term ‘‘socialism’’ held a particularmeaning in Soviet-type economies, basically consisting <strong>of</strong> (i)allocation <strong>of</strong> resources through central planning and elimination<strong>of</strong> markets for goods and labor; (ii) ownership <strong>of</strong> all major means<strong>of</strong> production by the state, representing the whole society, and theelimination <strong>of</strong> private enterprise; and (iii) distribution <strong>of</strong> income18 Logan, William. Protecting the Tay Nguyen gongs: Conflicting rights in Vietnam’scentral plateau. Cultural Diversity, Heritage and Human Rights, 2010.19 Ibid20 Duiker, William J. “Vietnam: the challenge <strong>of</strong> reform.” Current History 88, no.537 (1989): 177-178.33 Mark Portillo Constructing “Culture” 34