Langlois | Sakolsky | van der Zon - New Star Books

Langlois | Sakolsky | van der Zon - New Star Books

Langlois | Sakolsky | van der Zon - New Star Books

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

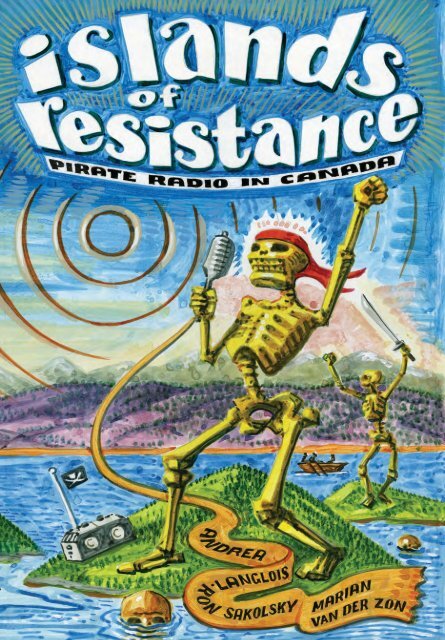

Islands of ResistancePirate Radio in Canadaedited byAndrea <strong>Langlois</strong>, Ron <strong>Sakolsky</strong>,& Marian <strong>van</strong> <strong>der</strong> <strong>Zon</strong>new star books • <strong>van</strong>couver • 2010

Islands of Resistance

Contents1. Setting Sail: Navigating Pirate Radio Waves in CanadaRon <strong>Sakolsky</strong>, Marian <strong>van</strong> <strong>der</strong> <strong>Zon</strong> and Andrea <strong>Langlois</strong> 32. Latitudes of Rebellion: Free Radio in an International ContextStephen Dunifer 233. Resistance to Regulation Among Early CanadianBroadcasters and ListenersAnne MacLennan 354. Freedom Soundz: A Programmer’s Journey BeyondLicensed Community RadioSheila Nopper 515. Secwepemc Radio: Reclamation of Our Common PropertyNeskie Manuel 716. Awakening the ‘Voice of the Forest’: Radio Barriere LakeCharles Mostoller 757. Squatting the Airwaves: Pirate Radio as Anarchy in ActionRon <strong>Sakolsky</strong> 898. Amplifying Resistance: Pirate Radio as Protest TacticAndrea <strong>Langlois</strong> and Gretchen King 101

9. The Care and Feeding of Temporary Autonomous RadioMarian <strong>van</strong> <strong>der</strong> <strong>Zon</strong> 11710. The Voyage of a Gen<strong>der</strong> Pirate & Her ToolboxBobbi Kozinuk 13311. Pirate Radio & Manoeuvre: Radical Artistic Practicesin QuebecAndré Éric Létourneau (translation by Clara Gabriel) 14512. Touch That Dial: Creating Radio Transcending theRegulatory BodyChristof Migone 16113. The Art of Unstable RadioAnna Friz 16714. Repurposed and Reassembled: Waking Up the RadioKristen Roos 18315. Radio Ballroom HalifaxStephen Kelly and Eleanor King (with Marian <strong>van</strong> <strong>der</strong> <strong>Zon</strong>) 19516. The Power of Small: Integrating Low-Power Radioand Sound ArtKathy Kennedy 20117. Voices in a Public Place: A Docudrama in Seven Actson/for Micro-Radio in CanadaRoger Farr 213Rip-Roaring Radical Resources 229Bibliography 233About the Contributors 240

List of IllustrationsCover: Maurice SpiraTable of Contents: Charlie the Headcase (illustration)Chapter 1: Moss Dance (illustration) www.rainbowraven.caChapter 2: Stephen Dunifer (photograph)Chapter 3: Duncan Macphail, (photograph) Source: in Duffy, Dennis.Imagine Please: Early Radio Broadcasting in British Columbia.(Victoria: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1983. 64.)Chapter 4: Matta (illustration)Chapter 5: Gord Hill (illustration)Chapter 6: Image 1: Charles Mostoller (photograph); Image 2: CharlesMostoller (photograph)Chapter 7: Tomás Hayek (collage)Chapter 8: Gretchen King (photograph)Chapter 9: Image 1: Sandra Morlacci (illustration); Image 2: GaryEugene (photograph)Chapter 10: “Wild and Infinite Flight” by Anais LaRue (illustration)Chapter 11: Image 1: Photomontage by Phillipe, still photographyby Jeff, courtesy of Diffusion système minuit du Québec archivecenter, Laval, Quebec (photomontage); Image 2: Photo takenby Pouf’s brother (photograph); Image 3: Abribec, suppôt de lanovelle humanité fiscale (http://www.iso1000000000.ch/abribec)(illustration)

• islands of resistanceChapter 12: “Absolute Final Intimacy of an Ear” by Chris McClaren(collage)Chapter 13: Image 1: Alexis O’Hara (photograph); Image 2: ClairePfeiffer (illustration)Chapter 14: Kristen Roos (illustration)Chapter 15: Andrea Lalonde (photograph)Chapter 16: Image 1: Destanne Lundquist (collage); Image 2: KathrynWalker (photograph); Image 3: Kathy Kennedy (illustration ofscore)Chapter 17: Jesse Gentes (collage)RRR Resources: Beehive Design Collective, anti-copyright, www.beehivecollective.org (illustration); Vrinda<strong>van</strong>esvari Conroy(illustration)

AcknowledgementsThe editors wish to acknowledge the Black Ink BC Anarchist Writers’Group and the Inner Island retreat where the idea for this bookwas born. We extend our gratitude to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Star</strong> <strong>Books</strong>: Rolf Maurer,Stefania Alexandru, Jamie Nadel and Michael Barnholden, for theirsupport of this project. A huge thanks to all of our intrepid authorsand incredible artists! We thank the ever fastidious Clara Gabriel forher work in translation. We acknowledge our pirate comrades DennisBurton (Radio Radio), Peter Cloud Panjoy (Free Radio Hornby), RobSchmidt (Free Radio Sundridge), Sean Coyote (Free Radio Cortes),Susan Kennard (Radio 90) for their early participation in this project.Finally, for their researching and networking tips, a tip of the hatto: Afua Cooper, Bob Sarti, Chantal Gutstein, Fre<strong>der</strong>ic Dubois, GayleYoung, Jane Parkinson, Jo Mrozewski, John Harris Stevenson, LeslieRegan Shade, Lorna Roth, Marc Raboy, Mary Vipond, Michel Sénécal,Naava Smolash, Pam Bullick, Sarita Ahooja and Steve An<strong>der</strong>son. Ronthanks Sheila Nopper for her indomitable pirate spirit. Marian thanksGary Eugene for his patience, direct action and piratical support. Sheextends this thanks to her family and friends, particularly to Asta,Alex and Linda. Andrea thanks her friends and family (especiallyMom, Dad, Rick, Mélanie and Clara), and Ken Tupper for jumpingaboard her pirate ship with his dictionary and spirited love of ideas.

moss dance

CHAP TER 1Setting SailNavigating Pirate Radio Waves in CanadaRon <strong>Sakolsky</strong>, Marian <strong>van</strong> <strong>der</strong> <strong>Zon</strong>and Andrea <strong>Langlois</strong>join us as we set sail for those islands of resistanceknown as pirate radio. Bypassing the treacherous waters of licensingand the doldrums of institutionalization, we have eschewed thefixed maps of entrenched power in favour of a cartography of autonomy.As navigators along these diverse routes, we have been guidedby an illuminated chart composed of pirate ports of call burning asbrightly as the star constellations relied upon by all mariners at sea.We begin our voyage in concrete terms — what is “pirate radio”?The use of the term pirate radio is a controversial one. It has beenburdened with the negative connotations of theft and mayhem, andexoticized with romantic swashbuckling imagery and Hollywoodproduction values. Perhaps the term “free radio” would carry less baggage,but we chose pirate radio because it is more immediately un<strong>der</strong>stoodby North Americans as referring to an unlicensed form of radiobroadcasting that relies on the airwaves for transmission, rather thanthe internet-based mechanisms of podcasting or web radio. As AnneMacLennan points out (Chapter 3), the word pirate had a pejorativering to it even in the 1920s and 1930s, being associated with predatoryUS broadcasters overriding the signals of Canadian-based stations.While this particular connotation might still exist in some quarters,for us it is the “no quarters” transgressive quality of the word pirate

• islands of resistancethat we embrace as inspiring to both the radical imagination and thepractice of direct action.If pirate is a word that has been used disparagingly by the radioindustry and its counterparts at the Canadian Radio-television TelecommunicationsCommission (CRTC), then we hereby reclaim it asa badge of honour. We prize the fact that it evokes an outsi<strong>der</strong> status 1in relation to the dominant cultural assumptions and practices of theradio industry and the government bodies that are theoretically supposedto regulate the airwaves in the “public interest.” As to those regulatoryagencies, in practice they have been captured by the very samevested interests within the radio industry that they are mandated tooversee. The legal climate in which they operate facilitates the corporatetheft of the airwaves and squelches autonomous alternatives witha bureaucratic arsenal of administrative rules and sanctions.In essence, what all radio pirates have in common is a refusal to obeythese legal edicts, whether out of a sense of political injustice, a defiantlibertarian ethos, a desire for self-realization or for purposes ofartistic expression. In this regard, what links the radio pirates in thisbook is that their projects can all be placed on a spectrum of illegality.On such a spectrum, illegality is viewed in a positive light rather thanvilified and dismissed. It is the transgressive nature of radio piracy— or “electromagnetic deviance” as André Éric Létourneau (Chapter11) describes it — that concerns us here. Transgression can takemany forms, from intentional interference with licensed broadcasts tofloating islands of sporadic insurrection and temporary autonomouszones, as well as more permanently-situated islands of resistance thatare rooted in geographical, ethnic, gen<strong>der</strong>ed or culturally-based formsof community.It is the interrelations and interactions among these transgressivepieces of the pirate radio puzzle that allow us to un<strong>der</strong>stand the largerpicture. The nomadic radio pirate strategically broadcasting the locationand movements of the police to global justice activists during theheat of confrontation in the streets engages in direct action by occupyingthe airwaves. So too is the stationary pirate radio broadcasterreporting on these events and their context to her community, as is theradio artist whose unlicensed broadcasts involve an aesthetic subversionthat reimagines the theory and practice of radio in public spaces.While someone could argue that one particular tactical use of radio ismore or less transgressive than another based on the type of illegality

Setting Sail • involved, we prefer to focus upon what might be called the “transgressivetrace” that animates them all.An interesting rubric that can be used to conceptualize the emancipatorypotential of such radio transgressions is what StevphenShukaitis calls a “minor cultural politics.” Here minor is not meantto diminish the importance of such a politics, but rather to situate itas a form of self-organization that may not be as grandiose as the allor nothing quality that revolutionary rhetoric allows, but which hasserious implications in liberating radical possibilities. “It is this formof politics based not upon projecting an already agreed upon politicalsolution or calling upon an existing social subject (the people, theworkers), but rather developing a mode of collective, continual andintensive engagement with the social world that embodies the politicsof minor composition.” 2 Shukaitis does not reference pirate radio inparticular as a form of minor cultural politics, but he does point to theoppositional aspects of punk culture (particularly invoking the subversiveirony embedded in the name of the band Minor Threat).Over the years many other theoretical approaches have been usedto conceptualize transgressive radio, several of which are personifiedwithin Roger Farr’s docudrama “Voices in a Public Space” (Chapter17). One of these theoretical wellsprings we wish to highlight here isthe work of Felix Guattari and Franco “Bifo” Berardi, who were coconspiratorsat the legendary Radio Alice in Italy during the headydays of the Autonomia movement of the seventies. It was their experiencesat Radio Alice that inspired them to call for the destructionof the hierarchical and centralized mass media model in favour of ade-territorialized proliferation of diverse and criss-crossing “enunciative”possibilities that they termed “popular free radio.” To accomplishthis emancipatory vision, Guattari imagined a “post-mediatic”world based upon “molecular self-organization” that anticipated themost libertarian aspects of the internet and cyberculture. 3 Instead ofthe system of “semiocapitalism,” Berardi envisioned “the creation of anew public space, autonomous from both state monopoly and privateeconomic domination.” 4 In keeping with his autonomist vision of telecommunications,Guattari chose the inspirational title “Millions andMillions of Potential Alices” for the preface to the French edition ofthe pamphlet Alice is the Devil, Free Radio Alice.Yet Radio Alice’s idea of free radio was vastly different from boththat of earlier offshore pirate stations such as Radio Caroline in the

• islands of resistanceUK, which was a commercial broadcaster, and the kind of “alternativeradio” that in subsequent years has characterized licensed campus/community radio stations in Canada. Extrapolating further on thesedifferences in his discussion of Guattari’s conception of Radio Alice,Michael Goddard noted:This is miles away both from ideas of local or community radio inwhich groups should have the possibility on radio to represent theirparticular interests and from conventional ideas of political radio inwhich radio should be used as a megaphone for mobilizing the masses. . . What this type of radio achieved most of all was the short-circuitingof representation in both the aesthetic sense of representing thesocial realities they dealt with and in the political sense of the delegateor authorized spokesperson in favor of generating a space of directcommunications. 5In this more expansive sense, Radio Alice actively challenged listenerpassivity and encouraged its audience members to become engaged indirect speech on the airwaves through relaying live call-ins aimed atunleashing strategic reports from the barricades, along with the unfilteredrage of protesters in the streets and the poetic laughter of theinsurgent imagination in flight. And, for the playful protagonists andprovocateurs of Radio Alice, if this could only be done illegally, thenso much more the merrier. As it turned out in the end, the more sombreresponse of the Italian state was arresting and imprisoning RadioAlice’s operators on charges of sedition, and shutting it down.What then would a spectrum of illegality look like in relation to thestories of radio piracy that you will encounter in the following chapters?While we do not want to fetishize the degree of illegality as proofof radicalism, one way of envisioning this spectrum is in relation tothe type of legal transgression involved. Not all forms of pirate radioinvolve the same perceived or actual risks. Within the wide arrayof programming that encompasses pirate initiatives from “permanent”radio stations to temporary broadcasters, it is a complicatedtask to decide where each pirate project fits on a spectrum of illegality.For example, the signal of a community-based pirate station onan indigenous reserve may be unlicensed and unwelcome in a nearbysettler community, but it has sovereignty protections not available offreserve.Similarly, a temporary broadcaster who is immersed in thetactical uses of pirate radio in protest situations seemingly faces a biggerrisk of getting busted than a temporary broadcaster whose chal-

Setting Sail • lenge to corporate and governmental stations might revolve aroundplaying dance music not available over the licensed airwaves. Unless,of course, in the case of the latter, there is a complaint from the mediamoguls whose market share is threatened.According to the CRTC, all unlicensed radio is illegal. Technically,this includes micro-radio, a form of narrowcasting, usually un<strong>der</strong>stoodas being less than five watts, as well as low-power transmissions,which are generally less than 100 watts. How far a signal couldbe broadcast at two watts or 100 watts would depend on geographyand antenna placement. 6 In the micro format, which is often used byradio artists, the risk of operating in Canada is typically interpreted asbeing very small. Beyond micro-radio, Canadian pirate radio in generaloccupies a niche that is unlicensed, and for the most part it fliesun<strong>der</strong> the radar; unless it is discovered accidentally by the authoritiesor there is interference with existing licensed broadcasters and acomplaint is lodged. In this case, the pirate broadcaster’s disruptionof the established pecking or<strong>der</strong> may be met with repression becauselegally sanctioned high-watt stations are automatically given a privilegedposition by the CRTC.Though diverse in their scope, all of the radio pirates in this bookconstitute a living assemblage of the frequencies of resistance. Whenviewed in this light, they can be un<strong>der</strong>stood as collectively having thewide-ranging potential to inspire a future movement of radio piracy inCanada. If the links we make here help to kick off increased resistanceto legal constraints and enhanced networking among radio resisters,then we will rejoice at the continuing power of both radio and thewritten word to subvert the established or<strong>der</strong>.While Canadian pirate radio initiatives may not, at present, constitutethe kind of movement that has been in evidence in recentyears among radio pirates in the United States, in some ways the roleof Bobbi Kozinuk, one of the writers in this volume (Chapter 10),might be seen as analogous to that of American pirate radio activistand foun<strong>der</strong> of Free Radio Berkeley, Stephen Dunifer, who also hasauthored a chapter in this book (Chapter 2). Like Dunifer, Kozinukhas facilitated numerous workshops on building micropower transmitters.These workshops have in turn been an impetus for the spreadof pirate radio throughout Canada. However, though both have beeninfluenced by the pioneering micropower radio work of Tetsuo Kogawain Japan, because Kozinuk is involved to a larger extent than Dunifer

• islands of resistancein the radio art community, her transmitter building workshops haveresulted in a greater proportion of Canadian pirates being sound artiststhan has been the case in the US. On the other hand, Dunifer’sinternational impact among radicalized grassroots radio pirates ismore widespread than that of Kozinuk. Yet, Kozinuk is not apolitical;she has used pirate radio as a tool in protest situations in Canada andcontinues to use pirate radio as a means to challenge social norms.Moreover, Canadian radio pirates do not seem to have any interestin promoting the kind of nationalist agenda that is sold to the listenersof the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) as “Canadianidentity.” They also typically resist the free market seductions of thecorporate sector, which has as its main goal the selling of audiences(potential consumers) to advertisers. Most Canadian radio piratestypically enjoy being independent of both, and free to fly the JollyRoger rather than the officially sanctioned flag of the nation state orthe branded banner of the multinational corporation. However, notall radio pirates would consi<strong>der</strong> themselves to be radical resisters ormovement activists. Radio pirates take over the airwaves illegally forvarious reasons. Some do so to maintain language and culture, or asa statement of indigenous sovereignty. Others wish to create communityor to protest domination. In some cases, the objective is to givedirect voice to the voiceless by strengthening the self-defined identityof a singularly-minded group or of a group that is more inclusive of thecomplexity of different geographical, ethnic and gen<strong>der</strong>ed realities.For some, the primary motivation is to create art or to devise a spaceof self-representation in relation to music, politics, the spoken word,sound art or radio drama. For others, their dedication to autonomousradio goes beyond content and becomes a participatory experiment inlateral organization and facilitates access to the skills and tools neededfor cultural production. Finally, some go on-air as pirates to exercisethe individual freedom to use radio in experimental and unconventionalways, such as the method of repurposing explored by KristenRoos (Chapter 14). In all cases, as pirates they exhibit the un<strong>der</strong>lyingphilosophy that the airwaves should be freely available.The context of who is a pirate radio practitioner has changed overtime. Anne MacLennan (Chapter 3) documents how, in the 1920s and1930s, competing bor<strong>der</strong> radio stations licensed in Mexico and the USwere consi<strong>der</strong>ed to be pirates by the CRTC because their signals overpoweredthose of Canadian stations. Today the definition of piracy is

not so much about interfering with licensed broadcasts as it is aboutengaging in any unlicensed programming activity, though intentionalinterference still occurs on occasion by politicized pirate broadcastersas is illustrated by André Éric Létourneau (Chapter 11). In the earlydays of Canadian radio, regulation was sparse, and many pirates whotook to the airwaves could slip between the loopholes of Canadian law.They were even joined in their rebellion against licensing by manyaudience members who refused to buy the required government-issuedlicences in or<strong>der</strong> to listen to the Canadian broadcasting service. 7Indigenous RootsSetting Sail • Although most examples of pirate radio in this book are containedwithin the settler-defined bor<strong>der</strong>s of what is called Canada, we feelthat it is important to indicate our discomfort with this demarcation.Accordingly, we acknowledge the many First Nations of TurtleIsland and the fact that the reserve-based radio broadcasters writtenabout here occupy or have occupied the airwaves that are part of colonizedand/or unceded indigenous territory. In effect, these broadcastsserve to question and challenge the Canadian government’s controlof the airwaves. As Neskie Manuel (Chapter 5) explains, not applyingfor a CRTC licence to broadcast is an acknowledgement that the Secwepemcpeople “did not give up our right to make use of the electromagneticspectrum to carry on our traditions, language and culture.”Similar claims of sovereignty are expressed by the Algonquin broadcastersfeatured in the Charles Mostoller essay on Radio Barriere Lake(Chapter 6).In this regard, it should be pointed out that Canadian radio piratesas a whole can trace their lineage back to the direct actions of indigenouspeoples in asserting their sovereignty, although not all indigenouspeoples who engage in unlicensed radio broadcasts would chooseto call themselves pirates. Even in terms of the history of the earliestlicensed community radio stations, indigenous radio played a seminalrole. It was some of the staff involved in an unlicensed 1969 low-powermobile station called Radio Kenonashwin on Ojibway territory, Longlac,Ontario, who later offered crucial advice and support in the settingup of Vancouver Co-op Radio (CFRO) in the early 1970s. 8One example of how the sovereignty struggles of indigenous peopleshave informed the historical development of pirate radio in a Cana-

10 • islands of resistancedian context is Akwesasne Freedom Radio, which was originallybased at the Mohawk reserve on the St. Lawrence River (encompassingOntario, Québec and <strong>New</strong> York State). Because the station crossedthe US/Canadian bor<strong>der</strong>, it was able to resist being licensed by eitherthe Canadian CRTC or the Fe<strong>der</strong>al Communications Commission(FCC) in the United States. Instead, it sought its approval to broadcastthrough a proclamation by the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation. AsCharles Fairchild has pointed out, “This arrangement was acknowledged,but not controlled by the CRTC, while the FCC refused to evenrecognize the station itself.” 9 However, when Akwesasne FreedomRadio went off the air, the Canadian fe<strong>der</strong>al government required itssuccessor, CKON, to apply for a licence to operate in 1982. The traditionalMohawk council of chiefs then began negotiating with theCRTC for regulatory rights. Eventually, according to Michael Keith,the CRTC avoided a confrontation by “recognizing the Mohawk’s abilityto regulate the station’s operation.” 10 Legally, then, we are left with aconfusing cross-bor<strong>der</strong> situation in which Keith says the CRTC “recognized”both the station and the regulatory power of the Mohawks,while Fairchild says the FCC “refused” to recognize the station at all.In any case, the CRTC was prevented from shutting down the stationlargely as a result of the kind of direct challenge to colonial authorityby Mohawk defen<strong>der</strong>s that would later be evidenced during the Okaconflict and the subsequent Kanesatake insurgency.Positioning Pirate Radio in the MediascapeWhile the indigenous concept of sovereignty is a very different constructfrom what in European terms is called the “commons,” bothchallenge control of the airwaves by the corporate state. In the lattercase, the airwaves are seen as an open public space where everyoneshould have equal access to the means of having their voice heard. InCanada, most media outlets — from public radio to newspapers — arewoefully inadequate in terms of encompassing, much less directlyrepresenting, the diversity of voices and identities that exist throughoutthe country. Instead, the mediascape is saturated with news, musicand culture tailored to market demographics and programming thatembodies and perpetuates the omnipresent representations of dominantideologies. When using the theoretical construct of the commons,which sees media as a social resource to be shared, the questions

[ chapter Setting title Sail ] • 11of who is being represented, and how, become paramount. Beyondnotions of representative democracy, one can alternatively conceptualizeun<strong>der</strong>ground organizational forms like pirate radio as being partof an “infrapolitical un<strong>der</strong>commons” that is often temporary and/orinvisible by design in or<strong>der</strong> to escape the gaze of power and preventenclosure. 11As a radical media strategy, occupying the airwaves can be viewedas a way to break down the hierarchies of access to meaning-makingthat are characteristic of licensed radio, thereby allowing grassrootsindividuals and marginalized groups not only a voice, but also theability to define their own realities. This constructive ability is associatedwith what Pierre Bourdieu refers to as “symbolic power.” 12 As NickCouldry points out, symbolic power is not evenly distributed in oursociety. This, he says, “has been an everyday fact of life in most societies,but it takes a particular form in contemporary mediated societies,where symbolic power is concentrated, particularly, although notof course exclusively, in media institutions, so that the uneven distributionof symbolic resources results in the overwhelming reality ofmedia power.” 13It is not simply the content and symbols presented in the mediaspherein and of themselves that indicate a concentration of power, but alsothe way that communication technologies have become centralized,marketed and developed in or<strong>der</strong> to concentrate media power in thehands of a few. While accessible two-way communication — a form ofcommunicating that breaks down the producer/audience dichotomy— has only recently been widely popularized through new technologiessuch as the internet, historically, as we have already seen, such ananti-authoritarian approach had been prefigured by pirate radio practitionersat Radio Alice. Even so, over thirty years later, most NorthAmericans still have trouble conceptualizing the possibility of usingthe airwaves to engage in passionate two-way communication. Forexample, the one-way kind of call-in show format — now a fixture ofmainstream radio — is a far cry from the freewheeling form that thecall-in took at Radio Alice. Instead of the dual flow of Radio Alice, thetype of call-in program with which most radio listeners are familiaris tightly controlled by host, producer and ultimately station management.Transgressing the boundaries of who has the ability to be heardby, and communicate with, others can be a powerful and transformativeexperience. Moreover, the very act of boldly taking over the air-

12 • islands of resistancewaves can be as important as what is communicated and how widelyit is disseminated. This book, then, is an examination of how someCanadian radio pirates have used unlicensed transmissions to occupyaural space, and to create meaning by fabricating islands of resistanceout of thin air.We, as media activists, reject the idea that radio is a hopelessly oldfashionedtechnology that is of no rele<strong>van</strong>ce in today’s high-tech world.In response to the question of why one might choose to use radio wavetransmissions when the internet has brought podcasting and webstreamingto our fingertips, we would respond that if pirate radio wassimply about sharing sounds and ideas across a geographic space, thenperhaps, yes, podcasting would be the preferred way to go. However,as Ron <strong>Sakolsky</strong> (Chapter 7) suggests, if pirate radio can be conceptualizedas a form of “squatting the airwaves,” then its potential challengeto the corporate state is rooted in the very nature of its unlawfulexistence, whereas podcasting offers no such direct confrontationwith state or corporate authority and seems to be perfectly legal. Yet,if we look to the Volomedia patent granted by the US in 2009 for controlof “the downloading of episodic media content” (i.e., podcasting),it has become clear that not even podcasting is safe from enclosure. 14As Tetsuo Kogawa has pointed out, the age of satellite communicationsand the internet will only leave more room for radio to exist inmicro-spaces. As he explains, “Change in a tiny space could resonateto larger space but without microscopic change no radical changewould be possible.” 15Sometimes, as is illustrated in Andrea <strong>Langlois</strong> and GretchenKing’s account (Chapter 8) of the use of pirate radio in protest situations,pirates use both the airwaves and web streaming together. Inone example they describe how this dual approach was effective ingarnering a mutually-reinforcing array of international, national,and local support for the protest. Yet, in rural contexts, it is preciselythe ubiquitous nature of the radio receiver that makes it the perfecttool. Most everyone has access to an inexpensive radio receiver butnot necessarily to a computer, especially in the Global South. Such awidespread pattern of technological dispersion is not true of newermedia technologies, and even if it should become so in the future, thedecidedly localized impact of low power radio is typically consi<strong>der</strong>eda plus rather than a minus in pirate radio circles. In fact, pirate radio

Setting Sail • 13might best be viewed as one element within an ensemble of autonomousmedia.As articulated by Christina Dunbar-Hester in her 2008 examinationof gen<strong>der</strong>, identity and activism with regards to low-power radio:Radio itself is viewed by some as a unique media technology, makingaccess to it very appealing: radio does not require producers orlisteners to be literate; it can reach a small, local community or area;production and broadcast technologies are relatively inexpensive andeasy to use; radio is very inexpensive to receive; and it is easier andcheaper to provide programming in an aural-only medium than ina tele-visual one. In spite of charges of radio being a dead or dyingmedium, both activists and corporate broadcasters view the FM bandas valuable. 16The importance of such accessibility is illustrated in CharlesMostoller’s essay about Radio Barriere Lake (Chapter 6), an indigenouscommunity where radios are a central feature of communication andthe radio station serves to link members of the community togetherculturally. In a similar vein, Stephen Dunifer’s essay (Chapter 2) onpirate radio activism among indigenous groups in Oaxaca serves toplace the Canadian experience in an international context. Even withthe advent of digital radio, we can assume that analog radio receiverswill not disappear, but might become a liberating alternative, or even acounter-hegemonic force, in relation to the mass media model of communication.Some hope that in the move to digital radio the FM bandwill be abandoned by corporate and state interests. Others fear that itwill instead be auctioned off to the highest bid<strong>der</strong>, leaving less spacebetween stations than currently exists, which means that pirates willhave difficulties finding empty spots on the FM dial.Radio Art with a Pirate TwistHistorically, one of the longest running above ground Canadian pirateradio micro stations has been the 1-watt voice of Radio 90 narrowcastingfrom the Banff Centre’s <strong>New</strong> Media Institute in Alberta. Becauseradios can be used as a mobile sound system, the airwaves can becomean artistic tool for creating interactive spaces and experiences as KathyKennedy, Kristen Roos, Christof Migone, André Éric Létourneau,Anna Friz, Stephen Kelly and Eleanor King, and Marian <strong>van</strong> <strong>der</strong> <strong>Zon</strong>

14 • islands of resistancedetail in their chapters. Kathy Kennedy (Chapter 16), for example, useslow-power radio to create concerts within public spaces or treasurehunts which are not about tuning in from home, but instead abouthow pirate radio can operate inclusively to allow audience participationand so transform the concept of performance accordingly.Another possibility for artistic uses of pirate radio involves whatsome call “radio parties” or “festivals” in which the broadcast is conductedwithin a convivial atmosphere. Such parties can be politicalgatherings of large numbers of people aimed at occupying public spaceto create temporary autonomous zones similar to those events manifestedby Reclaim the Streets, or they can involve more intimate andless overtly politicized settings. An example of the latter is illustratedby Anna Friz’s Radio Free Parkdale (Chapter 13) events in Toronto.In these situations, she and her housemates held radio parties duringwhich people could listen from home, or come to the party in personto participate in radio plays. In essence, then, one has the choice of listeningor getting behind the microphone. Relying primarily on wordof mouth within the neighbourhood to announce these upcominggatherings, these radio parties — like the larger Temporary AutonomousRadio (TAR) music festivals described by Marian <strong>van</strong> <strong>der</strong> <strong>Zon</strong>(Chapter 9) or the smaller events hosted by Stephen Kelly and EleanorKing of Radio Ballroom Halifax (Chapter 15) — are more about theevent itself and participation than about directly challenging accessto public space or being concerned with the range of transmission andhow many people might be listening at any given time.When such parties take place in public spaces, transmitters and portableradios replace sound systems. Using such a do-it-yourself (DIY)approach, in August 2008, a Montreal group called the Pirates of theLachine Canal threw a party where a 1-watt FM transmitter with arange of 100 feet was used to create a low-cost community event thatcould be easily moved if the police showed up. It did not require a largesound generator because the deejays plugged portable music devicesinto the transmitter’s console and party-goers brought their ownboom boxes. When Parks officials tried to shut down this self-organizedblock party because the Pirates did not have the permit requiredto hold a barbecue along the Lachine Canal, a local independent breweryloaned them their lawn and the party continued. 17 The officialsmade no mention of the illegality of the broadcast.

Setting Sail • 15Policing the AirwavesThere are two bodies that regulate radio in Canada, the CRTC andIndustry Canada. The CRTC deals with the “content, formatting andbenefits to society” 18 of radio transmission, while Industry Canadaoversees issues relating to the technical requirements of operating aradio station (wattage, interference, bor<strong>der</strong>s and use of the airwaves).The latter acts as the enforcement agency in cases of pirate radio transgression.For both regulatory bodies, any unlicensed radio in Canadais officially consi<strong>der</strong>ed illegal. “The Radiocommunication Act stipulatesthat no radio apparatus that forms part of a broadcasting un<strong>der</strong>takingmay be installed or operated without a broadcasting certificateissued by the Minister of Industry.” 19 Any station seeking a broadcastingcertificate or licence must apply for it. The granting of the licenceis by no means certain, and the application process requires extensivedocumentation, a sizeable capital outlay and an agreement to abide byCRTC rules regarding studio construction, procedures, language andcontent.Although unlicensed radio is deemed illegal in Canada, enforcementis typically complaint driven. Because Industry Canada is chronicallyshort-staffed, this lack of enforcement agents on their part limits theactive regulation of pirate radio. Sometimes Industry Canada staffdiscover a station at random and attempt to shut it down, but morecommonly complaints are made by individuals who are offended bythe content and/or language being broadcast, or else concerns arevoiced by commercial radio stations claiming interference with theirprogramming or reporting unlicensed broadcasting as a form of lawbreaking.Given the number of stations that we have become awareof which are, or have been, active in Canada over the years, it is fairto surmise that regulators do not view pirate radio as a high priorityor more stations would have been shut down than has been thecase. However, if Industry Canada representatives should knock ona radio pirate’s door, there are a number of options available. It hasbeen reported that these government enforcement agents typically askthat the pirate cease and desist — in other words, to quit broadcasting.If the station voluntarily complies, the Industry Canada personnelassigned to the case will likely leave it with only a warning. If voluntarycompliance is not forthcoming, then steps may be taken to con-

16 • islands of resistancefiscate equipment and levy fines. Finally, if the pirate station insistson continuing to broadcast illegally, theoretically it may be subject tocriminal and/or civil charges. 20It is difficult to ascertain how many pirate radio stations have beenshut down historically. In a 2009 phone interview, a representative ofIndustry Canada stated that they did not have this information, andsuggested that this lack of data is related to the dearth of pirate radiobroadcasts occurring within the country. 21 Yet only a few months later,Radio Free Cortes in British Columbia received an official letter thatthreatened them with shutdown unless they applied for a licence. In asubsequent phone interview, a representative from the CRTC arguedthat because “Americans are more politicized” 22 in relation to radiothan are Canadians, there are fewer pirate practitioners north of thebor<strong>der</strong>. In league with this stereotype of the apolitical Canadian whois quite satisfied with legally available radio options, Carla Brown, ajournalist working for the CBC has stated, “Canada has an extensivecommunity radio network that allows almost all types of content onthe air. Canadian pirates tend to do it as a hobby rather than a politicalstatement.” 23 Despite a commonality of opinion between IndustryCanada, the CRTC and CBC reporters like Brown, it has become clearto us in the course of compiling this volume that there are numerousand varied pirate radio practitioners across Canada. They are notmerely hobbyists doing <strong>van</strong>ity broadcasting, but are choosing to takeover the airwaves for a multitude of reasons, including political motivations.An interesting case in point that reveals the sometimes highly politicizednature of Industry Canada’s enforcement practices, occurredin February 2010 involving “Safe Assembly Radio,” an unlicensedVancouver low-watt station daring to broadcast views and opinionscritical of the corporate and patriotic spectacle known as the WinterOlympics. While claiming to have immunity from the CRTC’s rulesand regulations on pirate radio because it was a temporary art-relatedproject, combining its on-air broadcasts (which had a 3km radius)with internet streaming online from the artist-run VIVO Media ArtsCentre (one of the few Vancouver-based cultural groups which refusedto apply for Cultural Olympiad funding), after less than 24 hours ofbroadcast time the station was shut down by Industry Canada officers,who threatened VIVO as an organization with a fine of $25,000a day and with fines of $5,000 per day for each individual involved

Setting Sail • 17in the broadcasts. Curiously dressed for the occasion in Vancouver2010 jackets, the Industry Canada officials handed out business cardswhich sported a 2010 logo and e-mail address, and arrived to silencethe radio dissenters in a Vancouver Olympics Organizing Committee(VANOC) vehicle. 24In spite of an undisclosed history of similar enforcement measureson the part of Industry Canada, some writers have nevertheless maintainedthat the reason that there have not been as many pirate radiostations in Canada as in the States is because the openness of the Canadiancommunity radio sector makes piracy unnecessary. An exampleis Charles Fairchild’s argument presented in the 1998 book Seizingthe Airwaves. At that time, the FCC did not allow the issuance of lowpowerradio licences un<strong>der</strong> 100 watts. Today, his arguments must betempered by the existence of the FCC’s low-power FM (LPFM) programwhich came into being at the turn of the century as a result ofthe rapid growth of the pirate radio movement in the United States.However, the new LPFM option was arguably initiated by the FCC as adivide and conquer strategy. 25 In relation to that movement, some radiopirates had merely wanted licences and so became advocates of LPFM,while others refused to submit to having their broadcasts legally sanctionedand wanted nothing to do with licensing. Taking into accountwhat we consi<strong>der</strong> to be the FCC’s intentionally divisive goal for theLPFM service and the relatively small number of low-power licencesactually granted by the program in comparison to the number initiallypromised, we can see that the mission, scope and impact of the US communityradio sector is still quite limited in relation to access. However,with reference to licensed community radio outlets in Canada, SheilaNopper (Chapter 4) describes the increasingly restrictive nature of stations,such as CIUT in Toronto, as a possible impetus for the potentialflowering of Canadian pirate radio broadcasting in the future.While the Canadian regulatory regime gives lip service to the positiveweight allocated to social context and diversity of content inapproving new applications for community radio licences, the middlebrowatmosphere of the CBC and the market demographics of thecorporate sector are still what overwhelmingly characterize licensedprogramming. Moreover, their privileged position legally enableslicensed stations to expand their broadcast range at the expense of newcommunity radio applications. For example, in 2002, the proposedGabriola Co-op Radio station, on Gabriola Island in British Columbia,

18 • islands of resistancebegan the process of applying for a low-power community licence. Atthe time of this writing, they are still involved in the application process.26 Most recently, the delay was due to problems created by a subsequentapplication by Rogers Communications Inc. — which alreadyoperates a regional commercial station — to expand their broadcastrange. In this situation, the Rogers application was given legal prioritybecause they already held a licence as compared to the still unlicensedGabriola station’s earlier application. In 2000, a pirate stationon Hornby Island, another Gulf Island in British Columbia, was visitedby Industry Canada based on a complaint of illegal broadcastingand told to cease and desist. It complied and some of the programmersbegan the process of applying for a 5-watt developmental communitylicence. They are still mired in this application process as this bookgoes to press. Yet other former Free Radio Hornby pirates were neverinterested in being licensed in the first place and some have drifted toother pirate stations instead.ConclusionPirate radio, by its illegal and often ephemeral nature, is difficult todocument. In our research, we found a wide variety of stations plyingthe airwaves as pirates. We also met numerous dead ends, in largepart because it is so often a clandestine activity. Since documentinga pirate station may lead to its discovery by regulators, we respectthe decisions not to participate in this book that were made by thosepirates who did not want to have their stations profiled here out of aconcern about inadvertently increasing their vulnerability to shutdown.In other cases, we had leads, but were unable to find enoughtangible details to weave them into a story. Consequently, despite ourpersistent inquiries, there are inevitably gaps within this anthology.In that sense, while this book maps previously uncharted waters, it isnot definitive. We encourage others to fill in those gaps — from ethnicun<strong>der</strong>ground dance music stations in urban areas to rural stationsactively engaged in cultivating regional life-ways. It is indeed possiblethat once this volume is published, more historical and present-dayexamples of pirate radio will start to surface like formerly submergedislands of radio resistance arising from the depths of the sea. Others,no doubt, will choose to remain invisible. One thing is certain — theywill not cease to exist. After all, it is relatively easy to set up a pirate

adio station. Since the late 1980s with the advent of micropower technology,a 50-watt radio transmitter can be as small in size as a loaf ofbread. Moreover, a would-be pirate can now build her own transmittervery inexpensively, or, at a little more cost, or<strong>der</strong> one online. 27In our editorial deliberations, we seriously questioned whetherand how to document the stations and individuals that now appearwithin these pages, as it may bring them un<strong>der</strong> the radar of Canada’sregulatory bodies. In the end, we left it up to the individual practitionersthemselves as to whether or not they wanted to be included here.Pirate stations remain elusive, and perhaps this is essential for theirexistence. If we found them, we welcomed their participation in ourproject. If they chose to engage with us, we included their stories so asto inspire others to become part of the pirate radio experience as rea<strong>der</strong>s,listeners, practitioners, artists, educators, activists and outlaws.Welcome aboard!notesSetting Sail • 191. That outsi<strong>der</strong> status has been actively sought by some stations with permitsor licences and by web-based practitioners. Historically, an example from the1970s is the Calgary Cable FM station called Radio Radio, which existed for over35 years, and had the reputation of being a pirate station, even though it did infact have a permit. It did not broadcast over the airwaves — it cablecast — andhad strong community support as an alternative radio station with a distinctpirate ambience.2. Stevphen Shukaitis, “Dancing Amidst The Flames: Imagination and Self-Organization in a Minor Key,” in Subverting The Present, Imagining the Future:Insurrections, Movement, Commons, ed. Werner Bonefield (<strong>New</strong> York: Autonomedia,2008), 102.3. Franco (Bifo) Berardi, Felix Guattari: Thought, Friendship and VisionaryGeography (<strong>New</strong> York: Macmillan Publishers, 2008), 29–30.4. Franco Berardi, M. Jacquenot and G. Vitali, Ethereal Shadows: Communicationsand Power in Contemporary Italy, (<strong>New</strong> York: Autonomedia, 2009), 80.5. Michael Goddard, “Felix and Alice in Won<strong>der</strong>land: The Encounter betweenGuattari and Berardi and the Post-Media Era,” http://www.generation_online.org/p/fpbifo1.htm (accessed August 22, 2009).6. A more thorough explanation of the relationship between wattage and distanceof reception can be found in Chapter 9, “The Care and Feeding of TemporaryAutonomous Radio” by Marian <strong>van</strong> <strong>der</strong> <strong>Zon</strong>.7. For more information, see Anne MacLennan, Chapter 3.8. Charles Fairchild, “The Canadian Alternative: A Brief History of Unlicensedand Low Power Radio” in Seizing The Airwaves: A Free Radio Handbook,

20 • islands of resistanceed. Ron <strong>Sakolsky</strong> and Stephen Dunifer (San Francisco: AK Press, 1998), 50.9. Ibid., 51.10. Michael Keith, Signals In The Air: Native Broadcasting in America (Westport,Connecticut: Praeger Press, 1995), 88.11. Stefano Harney, “Governance and the Un<strong>der</strong>commons,” (2008), http://info.interactivist,net/node/10926 (accessed August 22, 2009).12. Nick Couldry, “Being Elsewhere: The Politics and Methods of ResearchingSymbolic Exclusion,” in The Politics of Place, ed. Cresswell, T. and Verstraete, G.(Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam/Rodopi Press, 2003), 109-124.13. Ibid., 1.14. Rebecca Jeschke, “EFF Tackles Bogus Podcasting Patent — And We NeedYour Help,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, November 19, 2009, http://www.eff.org/deeplinks2009/11/eff-tackles-bogus-podcasting-patent-and-we-needyou(accessed December 12, 2009).15. Tetsuo Kogawa, “A Micro Radio Manifesto” (2006). http://anarchy.translocal.jp/radio/micro/(accessed August 22, 2009).16. Christina Dunbar-Hester, “Geeks, Meta-Geeks, and Gen<strong>der</strong> Trouble:Activism, Identity and Low-power FM Radio,” Social Studies of Science, 38-2(April 2008), 203.17. Rupert Bottenburg, “All Hands on Deck!” Montreal Mirror, 14 August2008, 24, no. 9, http://www.montrealmirror.com/2008/081408/music1.html(accessed August 22, 2009). See also: www.myspace.com/piratesofthelachinecanal(accessed August 22, 2009).18. Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, website:http://www.crtc.gc.ca/eng/bctg-radio.htm (accessed August 22, 2009).There are limited exemptions where individuals can broadcast without alicence. See the CRTC’s Public Notice 2000-10 for more information. http://www.crtc.gc.ca/eng/archive/2000/PB2000-10.htm (accessed August 22, 2009).19. Industry Canada, Spectrum Management and Telecommunications, “BPR(broadcasting procedures and rules) -1 General Rules,” Issue 5 (January 2009),http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/smt-gst.nsf/eng/sf01326.html (accessed August 22,2009).20. For more information, see the Radiocommunication Act, Section 9 (forcriminal charges) and Section 18 (for civil charges), (15 June 2009), http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/ShowFullDoc/cs/R-2//20090707/en (accessed August 22, 2009).21. Personal telephone interview, Industry Canada representative, April 27,2009.22. Personal telephone interview, CRTC representative, April 27, 2009.23. Carla Brown, “Pirate Radio: a Voice for the Disenfranchised,” Peace andEnvironment <strong>New</strong>s, July-August 1996, http://www.perc.ca/PEN/1996-07-08/sbrown.html(accessed August 22, 2009).24. Dawn Paley, “VIVO Radio Signal Silenced by Industry Canada.” VancouverMedia Co-op, http://<strong>van</strong>couver.mediacoop.ca/story12769 (accessed March13, 2010).25. Ron <strong>Sakolsky</strong>, “The Myth of Government-Sponsored Revolution: A Cau-

Setting Sail • 21tionary Tale,” in Creating Anarchy (Liberty, Tennessee: Fifth Estate <strong>Books</strong>,2005).26. For more information on the Gabriola Co-op Radio process, see: http://members.shaw.ca/gabriolaradio/index.htm (accessed August 22, 2009).27. There are many resources available for would-be pirates. Please see theRip-Roaring Radical Radio References in this volume.

stephen duniferStudents building a transmitter in a workshop led by Stephen Duniferin Oaxaca, Mexico

CHAP TER 2Latitudes of RebellionFree Radio in an International ContextStephen Duniferin the international arena, “free radio” is theterm best suited to describe the ongoing rebellion against not onlycontrol of the broadcast airwaves through licensure and sanctions,but the neo-liberal/free market paradigm as well. Entering the lexiconaround the late 1960s, the term free radio was used to describe thebroadcasting efforts of offshore broadcasters, such as Radio Carolineand Radio Veronica, operating in Europe. Popular support was widespreadfor these “pirate” broadcasters who played music and aired programmingnot heard on the BBC and other state controlled services.Even community radio as a broadcast form did not exist in Europeat that time, and is still somewhat limited. Although specific detailsare often difficult to obtain on the global breadth and depth of freeradio broadcasting, the picture that emerges is one of a vibrant anduniversal movement. Unlike the rosters of community radio stationsmaintained by organizations like the World Association of CommunityRadio Broadcasters (AMARC), no central registry exists for freeradio broadcast stations — due in large part to the elusive nature ofthe activity itself.At its core free radio is an expression of immediacy and a rejectionof state and corporate control. From very early on free radio hasplayed a central role within popular struggles for liberation and selfdeterminationinternationally. Beginning in the late 1940s, Bolivian23

24 • islands of resistancetin miners began to create radio stations as part of a larger processto counter ongoing repression by autocratic government and militaryforces. Over a period of 20 years, approximately 30 radio stations wereestablished in the highland mining communities of Bolivia, most ofthem after the successful social uprising of 1952 that led to nationalizationof the mines. Despite their ultimate destruction following themilitary coup of 1981, the legacy of these stations remains as one of themost outstanding examples of grassroots radio in history. Apparentlythis is still well un<strong>der</strong>stood in Bolivia where new community radiostations, now numbering about 30 with a goal of at least 50, are carryingon the already established tradition of street radio. During theindigenous protests that eventually culminated in the election of EvoMorales, street reporters and community radio stations played a vitalrole in maintaining and increasing the effectiveness of the protests,blockades and strikes. Unlike what might be termed NGO (non-governmentalorganization) radio, such grassroots radio stations do notoriginate un<strong>der</strong> the auspices of a formal institution. Instead they arisefrom the participatory process of the community itself. As in the caseof the Bolivian tin miners, and many other similar situations, freeradio is a collective expression of the entire community. Full participationby the community is the heart of the radio station, not an afterthoughtor add-on as in the case of many so-called community radiostations.Arising from the specific needs and issues of the community, freeradio stations require no further legitimization other than that givenby the communities creating them; outside legitimization is only ameans by which to throttle expression, limit participation and stiflecontent. It is one thing to declare that free speech and uncensored communicationare human rights as stated by the United Nations’ (UN)Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but quite another struggleto act on these principles and assert control over the means of communication.Free speech, like other fundamental rights, is an inalienableright. It is as connected to human nature as breathing. Inalienablerights exist a priori; no institution or state can grant or confer them.Suppression, control and disregard, or protection and guardianshipare the only options left to state and institutional actors.Free radio has been integrated into a variety of popular struggles,from Radio Rebelde, established by Fidel Castro as part of the liberationof Cuba from the Batista regime, to Radio Venceremos in El

Latitudes of Rebellion • 25Salvador, and it has served as an important tool in the arsenal of theguerrilla forces fighting against the occupation of East Timor by Indonesia.It has become the voice of the favelas in Brazil where some 2000free radio stations exist without government sanction or approval.When threatened with closure by government agencies, communitiesarise to defend their voices. Mass strike actions by taxi drivers forcedthe Taiwanese government to abandon its effort to shut down un<strong>der</strong>groundradio stations in the mid-1990s. On numerous occasions indigenouscommunities have put their bodies between their radio stationand government forces attempting to shut them down. Following theZapatista uprising in Mexico in 1994, a subsequent call was made bySubcomandante Marcos in 1996 for the creation of an internationalnetwork of grassroots media. In response, independent communitymedia then entered a new period of revitalization and regrowth instep with a burgeoning anti-globalization movement. Many communityvoices had been silenced not at the barrel of a gun, but by neoliberalpolices which privatized the broadcast airwaves and mandatedtheir sale to the highest bid<strong>der</strong>. A single FM frequency or channel forthe entire country of El Salvador had a price tag of $100,000. Onerousregulatory policies combined with civil and monetary sanctions werebrought to bear against any community believing that they had theright of free speech and expression.For those who resist, the steel fist of state-sanctioned police ormilitary violence rests within the velvet glove of neo-liberalism andis enforced by a global corporate mafia. A handsome profit has beenmade in selling crowd suppression technology and weapons to bothdeveloping and first world countries as mass protests against corporateglobalization and neo-liberal policies have broken out on aninternational scale. Close on the heels of the arms merchants came thelawyers and consultants representing private security firms and mercenaries.To avoid an embarrassing repetition of the shutdown of theWorld Trade Organization’s (WTO) meetings in Seattle, steel cordonswere raised in Genoa, Prague, Cancun, and dozens of other cities toprotect the elite gatherings of the Group of Eight (G8) or WTO fromthe masses who were insisting that another world was possible. But,unlike people, radio waves cannot be easily fenced out. This is a primaryreason why free radio is consi<strong>der</strong>ed an ominous threat by thosewho wish to maintain their reign of domination and control. After all,the first paragraph in the Dictatorship for Dummies book states: “Seize

26 • islands of resistancethe radio stations dummy.” A slogan that evolved with Free RadioBerkeley goes like this: “If you cannot communicate, you cannot organize;if you cannot organize, you cannot fight back; and, if you cannotfight back, you have no hope of winning.”It may be difficult for people of First World media-saturated countriesto un<strong>der</strong>stand the importance of free radio and communitybroadcasting to social movements abroad. For example, during themid-1990s, a broadcast station was set up in the northern coastal farmingarea of Haiti. As part of a larger movement for land reform, thisstation began broadcasting what the market prices for crops should bein Creole, the native language. To many it is no big deal — just a farmreport. For the farmers, however, it was the difference between barelymaking it and not making it at all. It was common practice for cropbuyers to cheat the farmers by lying to them about the market prices.Without any means of knowing otherwise, the farmers un<strong>der</strong>soldtheir crops. The deception came to a grinding halt when the farmerswere informed of what the actual market prices were. Rich landownersand agricultural businessmen, threatened by these circumstancesand increasing incidents of land seizure by the peasants, hired localpolice to destroy the radio station and kidnap its principal organizer,the mayor of the town, who was one of the lea<strong>der</strong>s of the land reformmovement. Despite the destruction of the station and the woundingof a night watchman, the mayor eluded capture. After the situationhad calmed down a bit, the mayor demanded compensation from thegovernment for the loss of the equipment and facility. Surprisingly, heeventually received it, enough to replace the equipment and even buy amore powerful transmitter. For some, radio is just entertainment, forothers it is a lifeline.Within the context of indigenous peoples throughout the Americasconstituting themselves as one large community without bor<strong>der</strong>s andasserting their sovereignty, free radio and community broadcastingis construed as yet another sovereign right. With homes and villagesdestroyed by mud slides, rivers and lakes polluted, cancer rates offthe charts, mountains ripped open and laid bare and forests stripped,indigenous people are all too well aware of their role as the canary inthe coal mine of neo-liberal/free market fundamentalism. Moreover,free radio is a means by which they can preserve their languages, culturesand sovereignty. For indigenous people, the ability to communicateis a matter of life and death.

28 • islands of resistanceincluded one FM and one AM station as well. In so doing, they wroteanother chapter in the history of people, and most particularly women,seizing the means of communications and reclaiming what is theirs.By evening the women were broadcasting on Channel 9 with demandsfor the resignation of the governor. Videos by indigenous communitymembers followed the initial broadcast. For the next approximatelythree weeks, the indigenous communities saw what they have neverseen before on Channel 9 — themselves!In response to the occupation, armed paramilitaries and policeattacked the main transmitter and support equipment for Channel 9in the early morning hours of August 21. High velocity bullets rippedinto equipment, effectively putting Channel 9 off the air. One personwas wounded. As the word spread about this attack, a spontaneousmovement seized 12 to 15 commercial radio stations in Oaxaca City.Expecting to be attacked at any time, neighbourhoods and communitiesthroughout Oaxaca City organized a complex network ofbarricades and notification systems, using materials such as bells orfireworks to warn of an impending attack by the police and/or paramilitaries.The people were in control and the official government nolonger functioned in many parts of the state of Oaxaca.Humiliated by the turn of events, the governor and his allies in boththe Mexican government and private sector commenced a “dirtywar” against the popular assembly movement. Reminiscent of similartactics employed in Central America in the 1980s, people were “disappeared”and became targets of “random” shootings. One of the victimsof this “dirty war” was Brad Will, an American journalist withIndymedia and a documentary filmmaker. He was shot and killed onOctober 27, 2006 by police and paramilitaries acting on behalf of thegovernor. Interestingly enough, Brad had been involved in the creationof a free radio station, Steal This Radio, in <strong>New</strong> York City in themid-1990s. Increasing numbers of fe<strong>der</strong>al troops were brought in tocrush the popular rebellion. Finally, a force numbering approximately4000 were dispatched in November 2006 to recapture Oaxaca Cityand return it to “normalcy.” Despite repeated attacks, including beingstrafed with bullets, Radio Universidad continued to broadcast untilthe very end as the voice of the Oaxaca Commune. Police forces werenever able to invade and shut down the station. Fierce and determinedresistance prevented fe<strong>der</strong>al police from entering the university. Free

operational expenses, such as food and rental of facilities, these workshopsproved to be very cost effective — 24 radio stations for an averagecost of about US$600 per station. As proven in Oaxaca, radio hasan immediacy and flexibility that no other medium possesses. Allyou need is a transmitter, a properly situated antenna, a mixer, one ortwo microphones and a CD or mp3 player. Put everything on a table,make your connections, position the antenna and go on the air within15 minutes. Anyone within range with a radio is a potential listener.Some have suggested that radio is no longer necessary now that wehave the internet. Such a view is dangerously naïve. Sever a few criticalfibre optical cables and there goes the network. Further, it is veryFirst World-centric. For the equivalent cost of one or two computers(US$1,000–$1,500), a complete radio station covering a radius of eightto ten miles can be established.Future Directions in TechnologyLatitudes of Rebellion • 31As the June 2009 social unrest in Iran un<strong>der</strong>scored, not enoughemphasis can be placed on the necessity of having a decentralizedmeans of communications. With the digerati extolling the role andimpact of social networking sites, cell phones, and personal digitalassistants (PDA) on the ongoing protests in Iran, an obvious weaknessof these centralized networks has been exposed for all of those whocare to examine it. Iran’s communications network, installed by a jointventure of Nokia and Siemens, came with a monitoring centre whosecapabilities include the examination and control of every byte of datapassing through it. A process called deep packet inspection allowsfor the ability to troll for keywords and block any communicationscontaining those words. This is far more insidious and effective thanmerely blocking specific internet site locations which are assigned aunique address known as an IP address. IP address blocking can becountered by the deploying of proxy servers with constantly changingIP addresses, an activity cyber-activists have been engaged in tosupport the protests in Iran. Further, most cell phones now come withglobal positioning system (GPS) receivers, which allow for the user’slocation to be immediately known whether the cell phone is turned offor on. Ol<strong>der</strong> model cell phones can be tracked by tower triangulation.Software programs can be downloaded on cell phones to turn theminto monitoring devices for any conversations taking place within the

32 • islands of resistancerange of the microphone, all without the permission or awareness ofthe user. Such technologies may be much more Faustian than utopian,especially in light of programs such as Echelon and the installation ofFBI black box taps (known as Carnivore) on the servers of every internetservice provi<strong>der</strong>.Within this specific context, free radio becomes all the more importantbecause it cannot be centrally controlled and shut down. Everytool has both strengths and limitations and any intelligent user ofmedia tools must recognize this fact. Reliance on any one tool is foolishand short-sighted. Further innovations must be created and establishedto put technology to work for people and communities. CoryDoctorow, in his sci-fi novel, Little Brother, 1 shows a possible wayforward with the development of “extranets” — local wireless meshnetworks that allow for regional and local communications. Createdwith inexpensive wifi transceivers and software for self-configuration,extranets would be a way for local control of communications to beexerted. Software-defined radio receivers are yet another emergingpossibility.It cannot be denied that the internet has made the world muchsmaller, allowing information and news to flow in ways unimaginablea decade ago. Equally important to consi<strong>der</strong> though, is that informationwithout context is propaganda. De-contextualization is a primarymeans of control. Free radio is able to provide context in an immediateand direct manner. As part of a synergistic deployment of mediaand communications controlled by people, not corporations and government,free radio is a plant which only needs further watering andpropagation to maximize its inherent possibilities. Let a thousandtransmitters blossom!notes1. Cory Doctorow, Little Brother (<strong>New</strong> York: Macmillan/Tor-Forge <strong>Books</strong>,2008).

Women on-air, World War IIduncan macphail

Resistance to Regulation • 41until it was dropped completely in 1953. However, before the fee waseliminated, a lack of compliance with regulation in Canada extendedto listeners as well as broadcasters. As radio grew, so did its licensedradio receiver sets from 9,956 in the fiscal year ending March 31, 1923,to 297,398 by 1929. 15 Canadians were known to resent and evade thepayment of a licence fee, partly because Americans relied on privatelysponsored broadcasters and had no licence fees. The belief that radioshould be “free” persisted, especially since the majority of the populationlived close enough to the bor<strong>der</strong> to receive American radio signals,for which no paid licences were required.This early resentment might, in part, account for the continuedcritical view of the CBC and its broadcasts today in some quarters.Although the unwillingness to comply with licensing regulations canbe compared with contemporary efforts to surreptitiously obtain cabletelevision without payment, the phenomenon fits more comfortablyinto the mindset of the 1930s. Canadian census data in 1931 indicatedthat, for the first time, the urban population outnumbered the ruralpopulation (with urban communities defined as those greater than30,000). Living in sparsely populated areas, Canadians were unaccustomedto the many forms of regulation that increasingly expanded inthe twentieth century. The efforts to thwart radio inspectors in theirattempts to collect fees for radio receiving sets parallel the simultaneousefforts of Canadian rum runners and moonshiners that frequentlyhid their equipment in the woods or on farms. Prohibition — the banof the sale, manufacture and transportation of alcohol for consumption— extended from 1919 to 1933 nationally in the United States andfor variable time periods in each Canadian province during the firsthalf of the century. In fact, Toronto’s CKGW, owned and operated byGoo<strong>der</strong>ham and Worts Distillery, maintained a presence over the airwavesfor its products, legitimately marketed in Ontario, but was stilllargely banned in the vicinity of the station’s target audience immediatelySouth of CKGW in the United States, where its strong signalcould undoubtedly be heard. As an NBC affiliate, CKGW became themost active Canadian radio station in the North American broadcastingenvironment.Typically, densely populated countries report incidences of sharedlistening in pubs or other communal centres. However, the vast ruralnature of the greater part of Canada in the early twentieth centurymade this unlikely and at times impossible. Licence fees applied to

42 • islands of resistanceeach radio receiving set, which became a contentious issue with therapid spread of radio and the ownership of more than one set. Sharedlistening occurred more often in homes and among family members.Those without radios were acutely aware of the sounds of radio thatwafted out of their neighbour’s windows in the summer months. Theability to evade licence fees in small communities therefore dependedon the privacy afforded by isolation and the clannishness of communitythat protected the members from the perceived interference ofoutsi<strong>der</strong>s, such as radio inspectors.Being advertiser-supported and not requiring listener licences,American network broadcasting filled in the gaps, and provided competitionto Canadian public broadcasting. As late as 1937, stories andeditorials such as “Radio Licence Worries” in The Montreal Gazette,persisted in expressing the annoyance househol<strong>der</strong>s felt about theradio inspectors, who visited homes to check whether or not thehousehold possessed a valid radio licence. 16 The suspicion of and resistanceto radio licences was reinforced by the fraudulent sale of licencesin Saint John, <strong>New</strong> Brunswick. 17 The sale of more than a million radiolistening permits in Toronto was lauded, but many fines were anticipatedas 650 homes with receivers that had been licensed in 1935 didnot purchase permits in 1936. 18 While listeners typically resented thevery existence of licence fees, the price increase in 1938 provoked arenewed outcry against them. In that same year, 1002 complaints wererecorded in an internal CBC memo. The Department of Transportreceived 861 of the complaints and the remaining 141 went straight tothe CBC. 19 The same file also included a 22-page petition resisting thelicence fee increase.A newspaper editorial, entitled “Canadian Broadcasting System— Or Is It?” outlined most of the protests against the final increaseof the licence fee to $2.50 in 1939. It quoted Alex Frost, chairman ofthe radio committee, saying, “[n]ot only are we paying twice now, butwill be paying three or four times over according to the number ofsets owned, in the home, the car or summer camp.” 20 The editorialwent on to argue that “Radio subscribers... want to know if privatelyownedbroadcasting stations are riding free on the CBC system’s corporationprograms... why the Canadian system should be loaded upwith commercials, and then linked up with the American hookup formore commercials... and would like to know why Canada cannot havea CBC program free of commercial blabla entirely?” 21 The resentment

over licence fees became inextricably linked to the CBC, and popularperceptions of its role and potential as a publicly supported networkdependent on those fees. Other political commentators were incensedover the hardship inflicted upon the poor by the licence fee duringthe Depression of the 1930s. 22 Because the CBC had held the role ofnational network broadcaster and regulator of both private and publicbroadcasting across the country since 1936, it was placed in a positionof eternal conflict of interest unable to satisfy critics on all sides.Licence fees both supported operations and fed discontent with everyaspect of Canadian radio. 23Sharing FrequenciesResistance to Regulation • 43Another issue of concern to both listeners and broadcasters was interference.By 1930, the Radio Branch of the Department of Marine spent$250,000 annually to suppress what they deemed to be interference. 24Problems with interference were generally solved by the sharing offrequencies, with exceptions in larger cities. Most stations across thecountry did not broadcast full-time and shared frequencies as well asequipment and/or studios. Generally, early Canadian radio broadcasterswere not very well funded and could not have used the entirebroadcast day had it been available. Canadian cities were not largeenough to support many stations, so few conflicts arose over frequencysharing. The assignment of shared frequencies, prior to 1933, favouredlisteners because so many of them still used crystal sets, which madetuning more difficult. The greater radio coverage of the country by1939, when the CBC opened its last two powerful regional radio stationsin Watrous, Saskatchewan, and Sackville, <strong>New</strong> Brunswick, ma<strong>der</strong>adio reception better, and a choice of more than one station feasiblein areas distant from the American bor<strong>der</strong>.However, outside interference from American and Mexican stationsremained a problem for Canadian regulators. On December 12, 1935,K.A. MacKinnon of the Engineering Division submitted “A Reporton the Interference from Mexican Stations on the 840, 910 and 960Kc. Channels,” and noted that his program monitoring at Ottawa andStrathburn, Ontario, indicated the interference “between CRCT [aToronto CRBC station] and the Mexican-based station XERA was sufficientlystrong to ruin any listener’s enjoyment. In general XERA wasthe stronger.” 25 MacKinnon also examined interference between XENT

44 • islands of resistanceand CRCM (a Montréal CRBC station), and between CKY (a WinnipegCRBC affiliate station) and XEAW. He concluded that the interferencein these cases was minor and within the “assumed service range.”It is important to note that this equation of pirate radio with interferencewas about radio broadcasts that were usually directed atcapturing a larger audience in the United States while avoiding USregulations. XENT in Nuevo Laredo, XEAW in Reynosa, and XERAin Villa Acuna, called “bor<strong>der</strong> blasters,” migrated to Mexico from theUnited States. The stations, however, did not broadcast in Spanish, butin English. For instance, XERA was run by Dr. Brinkley, who gainedfame for his goat-gland surgeries to treat “lagging libido.” His treatmentsstarted in Milford, Kansas during the 1920s and his “goat-glandgospel” was broadcast over his radio station KFKB, one of the first inthe American Midwest. 26 After an increase in the radio station’s power,3000 letters came in a day inquiring about cures, until Dr. Brinkleycame un<strong>der</strong> attack when Dr. Morris Fishbein initiated a campaign torevoke Brinkley’s licence to practice medicine. 27Despite the fact that the station was operating un<strong>der</strong> a cloud due toa US Fe<strong>der</strong>al Radio Commission (FRC) investigation to potentiallyrescind its licence, KFKB was “voted the most popular radio station inAmerica in a survey conducted by the Chicago-based Radio Times.” 28Brinkley sold KFKB and started operations in Villa Acuna, Mexicowith greater power as XER in 1932 and XERA by 1935, following theexample of the “nation’s station” WLW, Cincinnati, Ohio. WLW wasgranted sufficient power by the Fe<strong>der</strong>al Radio Commission to beheard across the United States, but its directional antenna mo<strong>der</strong>atedthe strength of its signal in Canada. Similar to XERA however, XEAWand XENT, mentioned in MacKinnon’s report, and other stations,fled the regulation of the FRC for Mexico where they could broadcastto most of the United States and parts of Canada. Radio personalityWolfman Jack credits his career to bor<strong>der</strong> radio as featured in the 1973film, American Graffiti. 29 The long-standing practice of bor<strong>der</strong> radiojust south of the American frontier only ceased to interfere with Canadianradio stations after the Ha<strong>van</strong>a Treaty of 1937, when “tolerable”levels of radio interference by sky waves after dusk were determinedfor North America.Within Canada, interference drew the attention of regulators toboth legal and illegal stations. Attempting to enforce public standardsof morality, police seized thousands of dollars worth of radio equip-