Use of a Brief Food Frequency Questionnaire for Estimating Daily ...

Use of a Brief Food Frequency Questionnaire for Estimating Daily ...

Use of a Brief Food Frequency Questionnaire for Estimating Daily ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

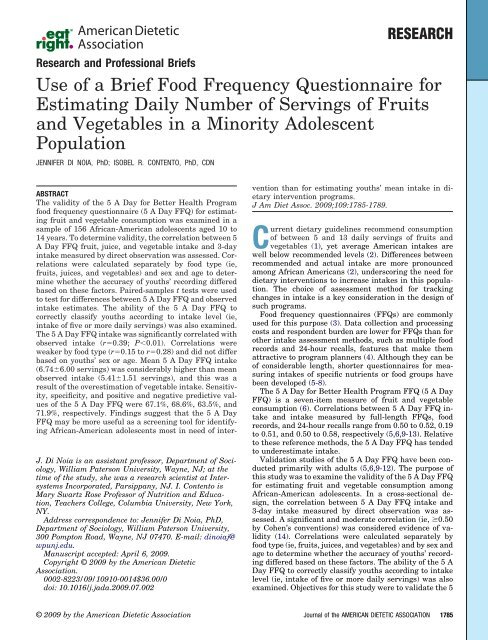

RESEARCHResearch and Pr<strong>of</strong>essional <strong>Brief</strong>s<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Brief</strong> <strong>Food</strong> <strong>Frequency</strong> <strong>Questionnaire</strong> <strong>for</strong><strong>Estimating</strong> <strong>Daily</strong> Number <strong>of</strong> Servings <strong>of</strong> Fruitsand Vegetables in a Minority AdolescentPopulationJENNIFER DI NOIA, PhD; ISOBEL R. CONTENTO, PhD, CDNJ. Di Noia is an assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essor, Department <strong>of</strong> Sociology,William Paterson University, Wayne, NJ; at thetime <strong>of</strong> the study, she was a research scientist at IntersystemsIncorporated, Parsippany, NJ. I. Contento isMary Swartz Rose Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Nutrition and Education,Teachers College, Columbia University, New York,NY.Address correspondence to: Jennifer Di Noia, PhD,Department <strong>of</strong> Sociology, William Paterson University,300 Pompton Road, Wayne, NJ 07470. E-mail: dinoiaj@wpunj.edu.Manuscript accepted: April 6, 2009.Copyright © 2009 by the American DieteticAssociation.0002-8223/09/10910-0014$36.00/0doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.07.002ABSTRACTThe validity <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day <strong>for</strong> Better Health Programfood frequency questionnaire (5 A Day FFQ) <strong>for</strong> estimatingfruit and vegetable consumption was examined in asample <strong>of</strong> 156 African-American adolescents aged 10 to14 years. To determine validity, the correlation between 5A Day FFQ fruit, juice, and vegetable intake and 3-dayintake measured by direct observation was assessed. Correlationswere calculated separately by food type (ie,fruits, juices, and vegetables) and sex and age to determinewhether the accuracy <strong>of</strong> youths’ recording differedbased on these factors. Paired-samples t tests were usedto test <strong>for</strong> differences between 5 A Day FFQ and observedintake estimates. The ability <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ tocorrectly classify youths according to intake level (ie,intake <strong>of</strong> five or more daily servings) was also examined.The 5 A Day FFQ intake was significantly correlated withobserved intake (r0.39; P0.01). Correlations wereweaker by food type (r0.15 to r0.28) and did not differbased on youths’ sex or age. Mean 5 A Day FFQ intake(6.746.00 servings) was considerably higher than meanobserved intake (5.411.51 servings), and this was aresult <strong>of</strong> the overestimation <strong>of</strong> vegetable intake. Sensitivity,specificity, and positive and negative predictive values<strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ were 67.1%, 68.6%, 63.5%, and71.9%, respectively. Findings suggest that the 5ADayFFQ may be more useful as a screening tool <strong>for</strong> identifyingAfrican-American adolescents most in need <strong>of</strong> interventionthan <strong>for</strong> estimating youths’ mean intake in dietaryintervention programs.J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1785-1789.Current dietary guidelines recommend consumption<strong>of</strong> between 5 and 13 daily servings <strong>of</strong> fruits andvegetables (1), yet average American intakes arewell below recommended levels (2). Differences betweenrecommended and actual intake are more pronouncedamong African Americans (2), underscoring the need <strong>for</strong>dietary interventions to increase intakes in this population.The choice <strong>of</strong> assessment method <strong>for</strong> trackingchanges in intake is a key consideration in the design <strong>of</strong>such programs.<strong>Food</strong> frequency questionnaires (FFQs) are commonlyused <strong>for</strong> this purpose (3). Data collection and processingcosts and respondent burden are lower <strong>for</strong> FFQs than <strong>for</strong>other intake assessment methods, such as multiple foodrecords and 24-hour recalls, features that make themattractive to program planners (4). Although they can be<strong>of</strong> considerable length, shorter questionnaires <strong>for</strong> measuringintakes <strong>of</strong> specific nutrients or food groups havebeen developed (5-8).The 5 A Day <strong>for</strong> Better Health Program FFQ (5 A DayFFQ) is a seven-item measure <strong>of</strong> fruit and vegetableconsumption (6). Correlations between 5 A Day FFQ intakeand intake measured by full-length FFQs, foodrecords, and 24-hour recalls range from 0.50 to 0.52, 0.19to 0.51, and 0.50 to 0.58, respectively (5,6,9-13). Relativeto these reference methods, the 5 A Day FFQ has tendedto underestimate intake.Validation studies <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ have been conductedprimarily with adults (5,6,9-12). The purpose <strong>of</strong>this study was to examine the validity <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ<strong>for</strong> estimating fruit and vegetable consumption amongAfrican-American adolescents. In a cross-sectional design,the correlation between 5 A Day FFQ intake and3-day intake measured by direct observation was assessed.A significant and moderate correlation (ie, 0.50by Cohen’s conventions) was considered evidence <strong>of</strong> validity(14). Correlations were calculated separately byfood type (ie, fruits, juices, and vegetables) and by sex andage to determine whether the accuracy <strong>of</strong> youths’ recordingdiffered based on these factors. The ability <strong>of</strong> the 5 ADay FFQ to correctly classify youths according to intakelevel (ie, intake <strong>of</strong> five or more daily servings) was alsoexamined. Objectives <strong>for</strong> this study were to validate the 5© 2009 by the American Dietetic Association Journal <strong>of</strong> the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION 1785

A Day FFQ as an assessment <strong>of</strong> fruit and vegetable consumptionamong African-American adolescents and determinethe effect <strong>of</strong> sex and age on the validity <strong>of</strong> the 5A Day FFQ.METHODSData were provided by African-American adolescents enrolledin a measurement validation study described elsewhere(15). Youths were recruited through summer daycamp programs <strong>of</strong>fered at youth services agencies in NewYork City. One hundred eighty one youths between theages <strong>of</strong> 10 and 14 years were enrolled. Because observationaldata used to validate the 5 A Day FFQ were collectedduring meals served during 3 consecutive days (asdescribed here later), evaluation <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ wasrestricted to youths who were present at all meals andthus <strong>for</strong> whom complete observational data were available(n156). Study procedures were approved by theInstitutional Review Board <strong>of</strong> Intersystems Incorporated.Prior to their study involvement, all youths providedwritten assent and in<strong>for</strong>med written consent was obtainedfrom a parent or guardian.Youths were served breakfast, lunch, and dinner atcollaborating sites during 3 consecutive days. At eachmeal, youths were given a tray with one serving each (asdefined by 5 A Day criteria) <strong>of</strong> fruits, juices, and vegetablesand were <strong>of</strong>fered a variety <strong>of</strong> main course options(16). Between meals, youths participated in recreationalactivities. They were not <strong>of</strong>fered fruits and vegetables tosnack on at these other times.Trained staff present at meals observed the amounts <strong>of</strong>fruit, juice, and vegetables youths left after eating byusing the plate-waste-by-visual-estimate method (17).They recorded the portion consumed <strong>of</strong> each serving on a<strong>for</strong>m that contained the following response options: zero,one fourth, one half, three fourths, and one. Becausemeals were served in a large-group <strong>for</strong>mat, each staffmember observed different groups <strong>of</strong> up to 10 youthseach; they did not concurrently observe the same youthsat each meal.After dinner on the third day, youths were administeredthe 5 A Day FFQ, a nonquantitative measure thatqueries the number <strong>of</strong> times respondents ate or drank thefollowing items during the previous month: 100% orangejuice or grapefruit juice; other 100% fruit juices; greensalad; french fries or fried potatoes; baked, boiled, ormashed potatoes; other vegetables; and fruit. The specificwording <strong>of</strong> items is shown in the Figure. Because thereference periods <strong>for</strong> the measures differed (ie, the precedingmonth vs the preceding 3 days, respectively), 5 ADay FFQ and observed intake estimates were convertedto a common metric. Youths’ 5 A Day FFQ responses weretrans<strong>for</strong>med to a daily equivalent and summed to providea composite measure <strong>of</strong> servings per day. Comparableestimates <strong>of</strong> observed intake were computed by determiningthe number <strong>of</strong> servings youths were observed eatingon each day and averaging these amounts across days.5 A Day FFQ and observed intake estimates by food type(ie, fruits, juices, and vegetables) were also calculated.The 5 A Day FFQ item <strong>for</strong> measuring intake <strong>of</strong> frenchfries and fried potatoes was excluded from scoring proceduresbecause these foods are high in fat and are notrecommended in the 5 A Day <strong>for</strong> Better Health ProgramIn the past month, how <strong>of</strong>ten did you drink or eat:100% orange juice or grapefruit juice?Other 100% fruit juices, NOT COUNTING fruit drinks?Green salad (with or without other vegetables)?French fries or fried potatoes?Baked, boiled, or mashed potatoes?Response options are: never, one to three times/month, one totwo times/week, three to four times/week, five to six times/week,one time/day, two times/day, three times/day, four times/day andfive or more times/day.In the past month, about how many servings <strong>of</strong> vegetables didyou eat, NOT COUNTING potatoes and salad?In the past month, about how many servings <strong>of</strong> fruit did you eat,NOT COUNTING juices?Response options are: none, one to three/month, one to two/week,three to four/week, five to six/week, one/day, two/day, three/day,four/day, and five or more/day.Figure. Questions asked on the 5 A Day <strong>for</strong> Better Health Program foodfrequency questionnaire.(18). French fries and fried potatoes were included in the5 A Day FFQ to help respondents distinguish them fromthe nonfried potatoes the measure was intended to count.The item <strong>for</strong> measuring these foods was specifically designedto identify and then omit them from intake estimates<strong>of</strong> recommended foods and juices (19). French friesand fried potatoes were not included in meals provided toyouths; thus, they were also not reflected in observedintake estimates.Pearson correlations were calculated to provide an index<strong>of</strong> relation between 5 A Day FFQ and observed intakeand intake by food type. To examine whether and how thecorrelations differed among the sex and age groups studied,youths were stratified by sex and age and separatecorrelations were calculated <strong>for</strong> males and females and<strong>for</strong> younger (ie, aged 10 to 11 years) and older (ie, aged 12to 14 years) youths. To determine whether pairs <strong>of</strong> correlations(eg, males vs females) were statistically different,the Fisher trans<strong>for</strong>mation method was used (20). Pairedsamples t tests were used to test <strong>for</strong> differences between5 A Day FFQ and observed intake estimates.To examine the ability <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ to correctlyclassify youths according to intake level, 5 A Day FFQand observed intake were dichotomized (fewer than fivedaily servings, five or more daily servings). The sensitivity,specificity, and positive and negative predictive values<strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ were examined using thesedichotomized scores. All analyses were conducted usingSPSS s<strong>of</strong>tware (version 12.0.1 <strong>for</strong> Windows, 2003, SPSSInc, Chicago, IL).RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONParticipants had a mean age <strong>of</strong> 11.89 (1.24) years andwere 55% female. Although 5 A Day FFQ intake wassignificantly correlated with observed intake (r0.39;P0.01), youths significantly overestimated their intakeusing the 5 A Day FFQ (t 155 2.97; P0.01) (Table).1786 October 2009 Volume 109 Number 10

Table. Comparison <strong>of</strong> daily servings <strong>of</strong> fruits, juices, and vegetables and servings by food type estimated by the 5 A Day <strong>for</strong> Better HealthProgram food frequency questionnaire and observed intakeIntake measure n a (meanSD c )5 A Day FFQ bRangeObservedintake(meanSD)Range5 A Day FFQminus observedintake(differenceSE d )Pvalue eTotal intakeAll cases 156 6.746.00 29.80 5.411.51 8.25 1.330.45 0.01 0.39**Male 70 6.305.05 19.93 5.301.54 6.67 1.000.57 0.08 0.34**Female 86 7.106.69 29.80 5.511.50 8.17 1.590.67 0.01 0.43**10-11 years 64 6.416.37 28.80 5.591.49 8.08 0.820.75 0.28 0.36**12-14 years 92 6.975.76 29.80 5.291.52 6.67 1.680.55 0.01 0.43**Fruit intakeAll cases 147 1.591.80 5.00 1.610.72 3.33 0.020.15 0.91 0.24**Male 64 1.311.59 5.00 1.490.78 2.92 0.180.20 0.37 0.32*Female 83 1.811.93 5.00 1.700.66 3.25 0.110.21 0.60 0.23*10-11 years 61 1.291.70 5.00 1.560.69 3.17 0.270.75 0.23 0.2012-14 years 86 1.811.86 5.00 1.650.75 2.92 0.160.20 0.42 0.25*Juice intakeAll cases 156 2.922.89 10.00 2.610.49 3.08 0.310.23 0.18 0.15Male 70 3.102.88 10.00 2.730.35 1.92 0.370.35 0.28 0.02Female 86 2.772.92 10.00 2.520.57 2.83 0.250.31 0.41 0.22*10-11 years 64 2.962.97 10.00 2.690.43 2.42 0.270.37 0.47 0.1012-14 years 92 2.892.86 10.00 2.560.52 2.83 0.330.29 0.25 0.18Vegetable intakeAll cases 156 2.322.95 15.00 1.260.68 4.67 1.060.23 0.01 0.28**Male 70 2.012.47 10.21 1.210.67 2.67 0.800.29 0.01 0.16Female 86 2.571.30 15.00 1.300.68 4.58 1.270.34 0.01 0.34**10-11 years 64 2.223.07 15.00 1.370.70 4.33 0.850.37 0.03 0.26*12-14 years 92 2.392.88 15.00 1.190.65 2.67 1.200.29 0.01 0.30**a For the fruit category, the sample size was reduced due to the omission <strong>of</strong> cases with missing data (n9).b 5 A Day FFQ5 A Day <strong>for</strong> Better Health Program food frequency questionnaire.c SDstandard deviation.d SEstandard error.e Values shown indicate the level <strong>of</strong> significance <strong>for</strong> paired-samples t tests comparing 5 A Day FFQ and observed intake.*Pearson correlation between 5 A Day FFQ and observed intake significant at P0.05.**Pearson correlation between 5 A Day FFQ and observed intake significant at P0.01.Correlation between5 A Day FFQ andobserved intakeThe correlations were weaker by food type and weresignificant <strong>for</strong> fruits (r0.24; P0.01) and vegetables(r0.28; P0.01), but not juices (r0.15; P0.05). 5 ADay FFQ intake <strong>of</strong> fruits and juices did not differ fromobserved fruit and juice intake. However, 5 A Day FFQintake <strong>of</strong> vegetables was significantly higher than observedvegetable intake (t 155 4.65; P0.01). Correlationsbetween 5 A Day FFQ and observed intake andintake by food type did not differ based on youths’ sex orage.Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictivevalues <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ were 67.1%, 68.6%,63.5%, and 71.9%, respectively. This means that 67.1% <strong>of</strong>youths with observed intake <strong>of</strong> fewer than five daily servingswere classified by the 5 A Day FFQ as consumingfewer than five daily servings, and 68.6% <strong>of</strong> youths withobserved intake <strong>of</strong> five or more daily servings were classifiedby the 5 A Day FFQ as consuming five or more dailyservings. Moreover, if the 5 A Day FFQ determined thatintake was fewer than five daily servings, it was correct63.5% <strong>of</strong> the time, and if it determined that intake wasfive or more daily servings, it was correct 71.9% <strong>of</strong> thetime. These per<strong>for</strong>mance indicators suggest that the 5 ADay FFQ is useful <strong>for</strong> confirming intake levels (as indicatedby its positive and negative predictive value) and itwill correctly classify sizable and similar proportions <strong>of</strong>youths with intakes below and at or above five dailyservings (as indicated by its sensitivity and specificity,respectively).This study examined the validity <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ<strong>for</strong> estimating fruit and vegetable consumption amongAfrican-American adolescents. The correlation between 5A Day FFQ and observed intake was below the a prioricriterion, an indication that the 5 A Day FFQ was not avalid measure <strong>of</strong> intake in this population. Noteworthy isthe heterogeneity <strong>of</strong> responses to 5 A Day FFQ items asindicated by the large range <strong>of</strong> values <strong>for</strong> 5 A Day FFQintake estimates. Although the reference period <strong>for</strong> the 5A Day FFQ is the preceding month, response optionsquery the number <strong>of</strong> times per month, week, or day respondentsconsumed the included items. The large variationfound may be an indication that youths had difficultyquantifying their monthly intake in daily andOctober 2009 ● Journal <strong>of</strong> the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION 1787

weekly equivalents, a factor that may account <strong>for</strong> the poorvalidity <strong>of</strong> the measure.The overestimation found was consistent with findingsfrom a validation study <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ in a sample <strong>of</strong>children (13). In that study, youths overestimated theirintake regardless <strong>of</strong> food type, whereas in this study,youths overestimated their vegetable intake only. A number<strong>of</strong> factors may explain this pattern.Observational data revealed that youths’ vegetable intakewas lower than their fruit and juice intake. Youths’tendency to consume more fruit (mostly through fruitjuice) than vegetables is consistent with intake patternsfound among African Americans in other research (21).Because youths consumed fruits and juices more <strong>of</strong>tenthan vegetables, they may have been recalled withgreater accuracy.Alternatively, the overestimation may be an artifact <strong>of</strong>the greater number <strong>of</strong> items used to measure vegetableintake. The 5 A Day FFQ uses three items to measurevegetable intake, two items to measure juice intake, andone item to measure fruit intake. In other research, reportedservings <strong>of</strong> fruits, juices, and vegetables increasedin direct proportion to the number <strong>of</strong> questions <strong>for</strong> measuringthese foods (22).Possibly, youths were influenced by social approval andsocial desirability biases, the tendencies <strong>of</strong> individuals torespond in a manner consistent with expected norms (23).Youths may have been aware that vegetables are foodsthey should be in the habit <strong>of</strong> eating. This awareness,combined with their low vegetable intake, may have encouragedthem to report consuming vegetables more <strong>of</strong>tenthan was the case.The small and self-selected sample limits the generalizability<strong>of</strong> findings. The time periods referenced by themeasures used differed. Youths may have had difficultytranslating servings consumed during 3 days to servingsconsumed in a month. Results may there<strong>for</strong>e underestimatethe true validity <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ. Respondentsdid not have the option <strong>of</strong> selecting from among a variety<strong>of</strong> fruits and vegetables at meals and they were not giventhese foods to snack on between meals. There was alsothe possibility that youths consumed additional fruitsand vegetables be<strong>for</strong>e and after camp. Thus, estimates <strong>of</strong>observed intake may not reflect youths’ true eating behavior.Previous research has shown that FFQs are susceptibleto seasonal reporting bias (24,25). Because thisstudy was conducted in the summer, results may be differentthan they would be at other times <strong>of</strong> the year.This study used observational data to validate the 5 ADay FFQ, a criterion measure superior to self-report measures(26). This is the first study to examine the validity<strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ among African-American adolescents.Findings advance understanding <strong>of</strong> the validity <strong>of</strong> thistool <strong>for</strong> estimating fruit and vegetable consumption inthis population.CONCLUSIONSThe poor validity <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQ suggests that it isless than optimal <strong>for</strong> program evaluation purposes. The 5A Day FFQ may overestimate the true intervention effector fail to find an effect on vegetable intake. Investigatorsare there<strong>for</strong>e encouraged to administer measures <strong>of</strong>known validity to confirm study findings based on the 5 ADay FFQ alone. The moderate sensitivity, specificity, andpositive and negative predictive value <strong>of</strong> the 5 A Day FFQsuggest that it may be more useful as a screening tool <strong>for</strong>identifying African-American youths most in need <strong>of</strong> intervention.The decision to use the 5 A Day FFQ <strong>for</strong>screening purposes should be based on tolerance <strong>for</strong> somemisclassification.STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST:No potential conflict <strong>of</strong> interest was reported by the authors.FUNDING/SUPPORT: The work under considerationwas supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute(CA 096162).References1. US Department <strong>of</strong> Health and Human Services, US Department <strong>of</strong>Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines <strong>for</strong> Americans, 2005. 6th ed. Washington,DC: US Government Printing Office; January 2005.2. Casagrande SS, Wang Y, Anderson C, Gary TL. Have Americansincreased their fruit and vegetable intake? Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:1-7.3. Hunt MK, Stoddard AM, Peterson K, Sorenson G, Herbert JR, CohenN. Comparison <strong>of</strong> dietary assessment measures in the Treatwell 5 ADay worksite study. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:1021-1023.4. Thompson FE, Byers T. Dietary assessment resource manual. J Nutr.1994;124(suppl 11):2245-2317.5. Warneke CL, Davis M, De Moor C, Baranowski T. A 7-item versus31-item food frequency questionnaire <strong>for</strong> measuring fruit, juice, andvegetable intake among a predominantly African-American population.J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:774-779.6. Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Kahle LL,Midthune D, Potischman N, Schatzkin A. Evaluation <strong>of</strong> 2 brief instrumentsand a food-frequency questionnaire to estimate daily number <strong>of</strong>servings <strong>of</strong> fruits and vegetables. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1503-1510.7. Thompson FE, Subar AF, Smith AF, Midthune D, Radimer KL, KahleLL, Kipnis V. Fruit and vegetable assessment: Per<strong>for</strong>mance <strong>of</strong> 2 newshort instruments and a food frequency questionnaire. J Am DietAssoc. 2002;102:1764-1772.8. Block G, Gillespie C, Rosenbaum EH, Jenson C. Rapid food screenerto assess fat and fruit and vegetable intake. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:284-288.9. Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, Kalsbeek WD,Dodds J, Cowan A, Jackson B, Mostinger B, Hoben K, Lashley J,Demissie S, McClelland JW. Fruit and vegetable consumption andprevention <strong>of</strong> cancer: The Black Churches United <strong>for</strong> Better Healthproject. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1390-1396.10. Snyder DC, Sloane R, Lobach D, Lipkus I, Clipp E, Kraus WE,Demark-Wahnefried W. Agreement between a brief mailed screenerand an in-depth telephone survey: Observations from the Fresh Startstudy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1593-1596.11. Kristal AR, Vizenor NC, Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Shattuck AL,McLerran D. Precision and bias <strong>of</strong> food frequency-based measures <strong>of</strong>fruit and vegetable intakes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:939-944.12. Plesko M, Cotugna N, Aljadir L. <strong>Use</strong>fulness <strong>of</strong> a brief fruit andvegetable FFQ in a college population. Am J Health Behav. 2000;24:201-208.13. Baranowski T, Smith M, Baranowski J, Wang DT, Doyle C, Lin LS,Hearn MD, Resnicow K. Low validity <strong>of</strong> a seven-item fruit and vegetablefood frequency questionnaire among third-grade students. JAmDiet Assoc. 1997;97:66-68.14. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis <strong>for</strong> the Behavioral Sciences. 2nded. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.15. Di Noia J, Contento IR. Criterion validity and user acceptability <strong>of</strong> aCD-ROM-mediated food record <strong>for</strong> measuring fruit and vegetableconsumption among black adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:3-11.16. Eat 5 Fruits and Vegetables a Day. Washington, DC: National CancerInstitute, National Institutes <strong>of</strong> Health; 1999. NIH Publication 99-3201.17. US Department <strong>of</strong> Agriculture, Economic Research Service. PlateWaste in School Nutrition Programs: Final Report to Congress. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/efan02009/efan02009.pdf. AccessedApril 12, 2006.1788 October 2009 Volume 109 Number 10

18. Thompson B, Demark-Wahnefried W, Taylor G, McClelland JW, StablesG, Havas S, Feng Z, Topor M, Heimendinger J, Reynolds KD,Cohen N. Baseline fruit and vegetable intake among adults in seven5 A Day study centers located in diverse geographic areas. J Am DietAssoc. 1999;99:1241-1248.19. Marcus AC, Heimendinger J, Wolfe P, Rimer BK, Morra M, Cox, D,Lang PJ, Stengle W, Van Herle MP, Wagner D, Fairclough D, HamiltonL. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among callers tothe CIS: Results from a randomized trial. Prev Med. 1998;27:S16-S28.20. Hays WL. Statistics. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston;1994.21. Subar AF, Heimendinger J, Patterson BH, Krebs-Smith SM, PivonkaE, Kessler R. Fruit and vegetable intake in the United States: Thebaseline survey <strong>of</strong> the Five A Day <strong>for</strong> Better Health Program. Am JHealth Promot. 1995;9:352-360.22. Krebs-Smith SM, Heimendinger J, Subar AF, Patterson BH, PivonkaE. Using food frequency questionnaires to estimate fruit and vegetableintake: Association between the number <strong>of</strong> questions and totalintake. J Nutr Educ. 1995;27:80-85.23. Miller TM, Abdel-Maksoud MF, Crane LA, Marcus AC, Byers TE.Effects <strong>of</strong> social approval bias on self-reported fruit and vegetableconsumption: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr J. 2008;7:118-124.24. Subar AF, Frey CM, Harlan LC, Kahle L. Differences in reported foodfrequency by season <strong>of</strong> questionnaire administration: The 1987 NationalHealth Interview Survey. Epidemiology. 1994;5:226-233.25. Fowke JH, Schlundt D, Gong Y, Jin F, Xia-Ou S, Wen W, Da-Ke L,Yu-Tang G, Zheng W. Impact <strong>of</strong> season <strong>of</strong> food frequency questionnaireadministration on dietary reporting. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:778-785.26. Resnicow K, Odom E, Wang T, Dudley WN, Mitchell D, Vaughan R,Jackson A, Baranowski T. Validation <strong>of</strong> three food frequency questionnairesand 24-hour recalls with serum carotenoid levels in asample <strong>of</strong> African-American adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:1072-1080.October 2009 ● Journal <strong>of</strong> the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION 1789