Improving Fire Hazard Assessment at the Urban-Wildland Interface ...

Improving Fire Hazard Assessment at the Urban-Wildland Interface ...

Improving Fire Hazard Assessment at the Urban-Wildland Interface ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

United St<strong>at</strong>esDepartment ofAgricultureForest ServicePacific SouthwestResearch St<strong>at</strong>ion<strong>Improving</strong> <strong>Fire</strong> <strong>Hazard</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong> <strong>at</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Urban</strong>-<strong>Wildland</strong> <strong>Interface</strong>: CaseStudy in South Lake Tahoe, CACenter for <strong>Urban</strong>Forest ResearchInternal Report<strong>Fire</strong>-1Lisa de Jong, Ph. D.AbstractA fire hazard assessment was conductedon priv<strong>at</strong>e, developed lots in South LakeTahoe, a high fire hazard urban-wildlandinterface community in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn California.<strong>Fire</strong> hazard was assessed in terms of <strong>the</strong>minimum standards set forth in <strong>the</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional<strong>Fire</strong> Protection Associ<strong>at</strong>ion’s (NFPA)Standard 299 and homeowner practicessuch as compliance with <strong>the</strong> fire safety lawPRC 4291, construction m<strong>at</strong>erials of <strong>the</strong>home, and irrig<strong>at</strong>ion. In addition, <strong>the</strong>influence on small parcel fire hazard byneighbors was assessed.Results indic<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> overall firehazard r<strong>at</strong>ing for <strong>the</strong> city was rel<strong>at</strong>ively lowbecause of its good roads, w<strong>at</strong>er, signage,and firefighting resources. However, <strong>the</strong>citywide non-compliance r<strong>at</strong>e for propertymaintenance was 66%, <strong>the</strong> citywide noncompliancer<strong>at</strong>e for defensible space was86% when adjusted for small parcel size,and 57% of <strong>the</strong> parcels were non-compliantfor both defensible space and maintenance.Clearly, homeowners in South LakeTahoe rarely choose for fire safety eventhough <strong>the</strong> city’s infrastructure is good.Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, results demonstr<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong>assessing <strong>the</strong> city’s fire hazard using NFPA299 alone will underestim<strong>at</strong>e a parcel’s firehazard. Including an analysis of compliancer<strong>at</strong>es and homeowner practices will providea more accur<strong>at</strong>e estim<strong>at</strong>e of individual firehazard.IntroductionThe m<strong>at</strong>rix of homes and landscaping th<strong>at</strong>make up <strong>the</strong> urban forest of urban-wildlandinterface (UWI) communities is defined as afuel m<strong>at</strong>rix by <strong>the</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional <strong>Fire</strong> ProtectionLISA DE JONG is a research forester <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>Pacific Southwest Research St<strong>at</strong>ion, Center for<strong>Urban</strong> Forest Research, One Shields Ave.,Rm. 1103, Davis, CA 95616

Associ<strong>at</strong>ion (NFPA 299). In contrast towildland areas, this fuel m<strong>at</strong>rix requiresactive homeowner involvement in firehazard mitig<strong>at</strong>ion. This necessity hasresulted in regul<strong>at</strong>ions governing <strong>the</strong>landscaping practices by priv<strong>at</strong>e landownersin <strong>the</strong> high fire hazard areas of California(CA PRC 4291). Designed with <strong>the</strong>importance of fuels reduction and structuresurvivability in mind (Brown 1994, Cohen1995, Tran 1992, Foote 1991), PRC 4291requires defensible space for <strong>at</strong> least 10meters around <strong>the</strong> home. It limits ahomeowner’s choice of plant species,density, and placement and regul<strong>at</strong>esmaintenance practices such as pruningtrees and removing ladder fuels.Though compliance with PRC 4291 mayincrease fire safety, <strong>the</strong> law does notrecognize (1) <strong>the</strong> variability in <strong>the</strong> individuallandscaping preferences th<strong>at</strong> people have,or (2) <strong>the</strong> impact of neighboring parcels on ahomeowner’s fire hazard. Residents <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>UWI have unique, individual sets of valuesand preferences th<strong>at</strong> are reflected in <strong>the</strong>landscapes <strong>the</strong>y cre<strong>at</strong>e and maintainaround <strong>the</strong>ir homes. These values oftenconflict with <strong>the</strong> principles of fire safety butproperty owners resist fire-safe regul<strong>at</strong>ionsif <strong>the</strong>y detract from wh<strong>at</strong> is valued in <strong>the</strong>landscape (Manfredo 1990, Abt 1991,Bailey 1991, Cortner 1991, Foote 1991,Smith 2001, Hodgson 1993, Winter 2000).In some communities, <strong>the</strong> combin<strong>at</strong>ion of<strong>the</strong>se two problems – small lot size andlandscape preferences – poses a significantbarrier to effective individual and communityfire hazard mitig<strong>at</strong>ion.This report describes a fire hazard analysisconducted on priv<strong>at</strong>e, developed lots inSouth Lake Tahoe, California. South LakeTahoe is a high fire hazard UWI communityin Nor<strong>the</strong>rn California where many of <strong>the</strong>developed lots are noncompliant with PRC4291 even though <strong>the</strong>re is active agencyoutreach and public support of fuelsreduction on undeveloped lots (Garrett,pers. comm., Harcourt, pers. comm.). <strong>Fire</strong>hazard was assessed according to <strong>the</strong>standards in NFPA 299, compliance withPRC 4291, construction m<strong>at</strong>erials of <strong>the</strong>home, irrig<strong>at</strong>ion practices, and <strong>the</strong> influenceon a parcel’s fire hazard by its immedi<strong>at</strong>eneighbors.Results indic<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> overall fire hazardscore for <strong>the</strong> city was rel<strong>at</strong>ively low becauseof infrastructural components such as goodroads, w<strong>at</strong>er availability, signage, andfirefighting resources. Analysis of <strong>the</strong>components th<strong>at</strong> involve homeowner choiceonly (e.g. defensible space, maintenance,irrig<strong>at</strong>ion, and construction m<strong>at</strong>erials)indic<strong>at</strong>ed limited individual, parcel-scale firehazard mitig<strong>at</strong>ion efforts.Study siteSouth Lake Tahoe has approxim<strong>at</strong>ely24,000 inhabitants and is loc<strong>at</strong>ed on <strong>the</strong>south shore of Lake Tahoe, adjacent to <strong>the</strong>Nevada border. The gre<strong>at</strong>er Lake TahoeBasin extends across 88,000 hectares intwo st<strong>at</strong>es (California and Nevada) and fourcounties (El Dorado, Placer, Douglas andNevada). Its elev<strong>at</strong>ion ranges fromapproxim<strong>at</strong>ely 1900 m <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface of <strong>the</strong>lake to about 3300 m <strong>at</strong> Freel Peak.Historically, fires in <strong>the</strong> Tahoe Basin wereprobably low and medium intensity surfacefires, occurring every 15 – 25 years andconsuming mostly light surface fuels, rarelybecoming stand-replacing events (Skinnerand Chang 1996). Eighty-five years of firesuppression in <strong>the</strong> basin (Murphy andKnopp 2001) combined with recent,prolonged drought conditions and extensivebug-kill have led to a build up of highlyflammable, hazardous fuel conditionsthroughout <strong>the</strong> area.The dominant conifer species in <strong>the</strong> lowermontane zone is ponderosa pine (Pinusponderosa), with some white fir (Abiesconcolor), incense cedar (Calocedrusdecurrens), and sugar pine (P. lambertiana).The upper montane zone (approx. 2000 –3000 m) is domin<strong>at</strong>ed by Jeffrey pine (P.jeffreyi) and also contains red fir (A.2

magnifica), white fir, western white pine (P.monticola) and some pure stands oflodgepole pine (P. contorta). In <strong>the</strong>subalpine zone (above 3000 m) speciesinclude whitebark pine (P. albicaulis) andmountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana)(Manley and Schlesinger 2001).The average January temper<strong>at</strong>ure for <strong>the</strong>basin is slightly below 0° C, <strong>the</strong> averageJuly temper<strong>at</strong>ure is approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 16° C,and <strong>the</strong> average annual precipit<strong>at</strong>ion is 74cm. Average annual snowfall ranges from2.5 m <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> elev<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> lake to almost 9m in <strong>the</strong> mountains. At lake level, <strong>the</strong>re areon average only 70 – 100 frost-free daysper year (U. S. Environmental D<strong>at</strong>a Service2000).Archaeological evidence suggests th<strong>at</strong>human habit<strong>at</strong>ion of <strong>the</strong> Tahoe Basin beganwith <strong>the</strong> ancestors of <strong>the</strong> Washoe N<strong>at</strong>iveAmericans, who entered <strong>the</strong> Basin after <strong>the</strong>Sierran glaciers retre<strong>at</strong>ed 8,000 to 9,000years ago. The first non-N<strong>at</strong>ive settlersarrived in <strong>the</strong> basin after <strong>the</strong> discovery ofgold and silver in nearby Virginia City,Nevada. Early industry included logging,ranching, grazing and fishing. By <strong>the</strong> earlytwentieth century, less than half of <strong>the</strong> presettlementforest in <strong>the</strong> Tahoe Basinremained. While timber harvestingdecreased, grazing and ranching continuedbecause of <strong>the</strong> need for farm products for<strong>the</strong> basin’s expanding popul<strong>at</strong>ion.Management agencies and consortiumswere developed in <strong>the</strong> Lake Tahoe Basin tomitig<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> neg<strong>at</strong>ive ecological impacts of<strong>the</strong> basin’s growing popul<strong>at</strong>ion. Among <strong>the</strong>most visible are <strong>the</strong> Tahoe RegionalPlanning Agency (TRPA), <strong>the</strong> USDA ForestService’s Lake Tahoe Basin ManagementUnit (LTBMU), and Tahoe Re-Green. TheTRPA is a powerful regul<strong>at</strong>ory organiz<strong>at</strong>ionwhose primary objective is to develop landuse and management standards th<strong>at</strong>maximize environmental health and mitig<strong>at</strong>eneg<strong>at</strong>ive environmental impacts fromdevelopment (Murphy and Knopp, eds.2000). Since <strong>the</strong> early 1970s, TRPA hasprohibited development on environmentallysensitive parcels and has regul<strong>at</strong>ed priv<strong>at</strong>elandowners’ management of <strong>the</strong>ir ownparcels. To compens<strong>at</strong>e landowners, <strong>the</strong>LTBMU and <strong>the</strong> California St<strong>at</strong>e TahoeConservancy have purchased many of<strong>the</strong>se lots. The LTBMU also plays an activerole in fuel management on <strong>the</strong>undeveloped urban lots owned by <strong>the</strong>Forest Service. Tahoe Re-Green is aninteragency consortium th<strong>at</strong> aims to educ<strong>at</strong>eresidents and help <strong>the</strong>m reduce fire hazardby removing fuels on priv<strong>at</strong>ely owned land.MethodsSampling sites were chosen from apopul<strong>at</strong>ion of approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 6,500 singlefamilyresidential parcels. These parcelswere str<strong>at</strong>ified into low, medium, and highcanopy cover and into low, medium, or highdensity residential. A proportional alloc<strong>at</strong>ionmethod was used to determine <strong>the</strong> numberof parcels to be sampled within eachstr<strong>at</strong>um. In total, 102 parcels across <strong>the</strong> citywere sampled. The veget<strong>at</strong>ion andstructural characteristics of each parcelwere measured and mapped.The city was divided into six neighborhoodsbased on observed differences inveget<strong>at</strong>ion, lot, and building characteristics(Fig. 1) (de Jong, in review). The initialocular classific<strong>at</strong>ion was refined throughst<strong>at</strong>istical analysis for homogeneity in eachof <strong>the</strong> defined neighborhoods. Theboundaries of each neighborhoodencompass built areas within city limits andexclude unbuilt areas such as parks andgolf courses. Major roads defined <strong>the</strong>boundaries between adjacentneighborhoods.Neighborhood 1 was <strong>the</strong> Tahoe Keys,characterized by wide streets, canals, large,new homes and planted exotic veget<strong>at</strong>ionand turf grass. There was no significantslope on any of <strong>the</strong> parcels found in thisneighborhood. Neighborhood 2 – 5 weresimilar to one ano<strong>the</strong>r in terms of smallparcel and home size. Their veget<strong>at</strong>ion was3

domin<strong>at</strong>ed by n<strong>at</strong>ive conifer species with asparse assortment of exotic shrubs ando<strong>the</strong>r plants, though <strong>the</strong> speciescomposition and structure differed betweenneighborhoods. Some parcels were slightlysloped. Neighborhood 2 encompassed alarge area surrounding <strong>the</strong> “Y,” or <strong>the</strong>junction of Highways 50 and 89, including<strong>the</strong> tracts of Gardner Mountain, TahoeVista, Tahoe Island, St<strong>at</strong>e Name streets,and <strong>the</strong> area around <strong>the</strong> hospital.Neighborhood 3 was <strong>the</strong> tract consisting of<strong>the</strong> north-central part of <strong>the</strong> city.Neighborhood 4 was <strong>the</strong> Sierra Tract.Neighborhood 5 contained <strong>the</strong> Bijou and AlTahoe tracts. Neighborhood 6 was <strong>the</strong>affluent area of Heavenly Ski Resort andwas characterized by large, new homes,large lots, and dominance of n<strong>at</strong>ive coniferspecies. Slopes in this neighborhood weresignificant.A fire hazard analysis was conducted oneach parcel and <strong>the</strong>n compared qualit<strong>at</strong>ivelyto <strong>the</strong> fire hazard of neighboring parcels.The assessment was based on NFPA 299,which assigns a number score for riskfactors, compliance with PRC 4291,construction m<strong>at</strong>erials, and irrig<strong>at</strong>ion. Higherscores reflect higher fire hazard.Figure 1. -- Neighborhoods and characteristic lots as defined for this study. 1- Tahoe Keys; 2 – The Y; 3-North Central; 4- Sierra; 5- Bijou; 6- Heavenly.Lake Tahoe35 61424

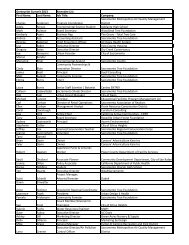

The law (PRC 4291) requires homeownersto prune dead branches, clear needles ando<strong>the</strong>r litter from roofs and gutters, covervents with wire mesh, and clear treebranches for 3 m around chimney outlets.Characteristics known to contribute tostructural ignition potential, such as a woodroof and single-paned windows (Foote1991, White 2000, Quarles 2001, Quarles2002), were also r<strong>at</strong>ed.Compliance with PRC 4291 was analyzed interms of <strong>the</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ion of defensible spacealone, maintenance alone, and <strong>the</strong>combin<strong>at</strong>ion of defensible space andmaintenance. Parcels demonstr<strong>at</strong>ing little orno defensible space were r<strong>at</strong>ed noncompliant.Parcels th<strong>at</strong> were non-compliantwith one or more of PRC 4291’smaintenance requirements were alsoconsidered non-compliant.Parcels were fur<strong>the</strong>r assessed for presenceof irrig<strong>at</strong>ion, construction m<strong>at</strong>erials, parcelsize, and <strong>the</strong> presence of hazardous decks.Defensible space r<strong>at</strong>ings were adjusted forsmall parcels to account for neighboringveget<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong> would influence <strong>the</strong> parcel’sfire hazard. Decks were consideredhazardous if <strong>the</strong>y were made of wood andgre<strong>at</strong>er than 0.5 m high and were openunderne<strong>at</strong>h or had flammable m<strong>at</strong>erialstored underne<strong>at</strong>h <strong>the</strong>m.Parcels were classified as small and under<strong>the</strong> direct influence of <strong>the</strong> fire hazard ofimmedi<strong>at</strong>e neighbors if <strong>the</strong> distancebetween <strong>the</strong> house and <strong>the</strong> side boundariesof <strong>the</strong> parcel was less than 7 m on ei<strong>the</strong>rside, if <strong>the</strong> difference between <strong>the</strong> totalwidth of <strong>the</strong> parcel and <strong>the</strong> total width of <strong>the</strong>house was less than 14 m, or if <strong>the</strong>difference between <strong>the</strong> total length of <strong>the</strong>parcel and <strong>the</strong> total length of <strong>the</strong> house wasless than 14 m. Larger parcels wereconsidered independent of neighboringparcels.The fire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ings of <strong>the</strong> individualsmall parcels were adjusted to include <strong>the</strong>fire hazard of neighboring parcels. Smallparcels with good defensible space and“rel<strong>at</strong>ively better” maintenance were r<strong>at</strong>ed<strong>the</strong> same for defensible space as a mediumor large parcel with moder<strong>at</strong>e defensiblespace. Small parcels with good defensiblespace and “same” rel<strong>at</strong>ive maintenancewere r<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> same for defensible spaceas a medium or large parcel with gooddefensible space.Neighborhoods were assigned a mean firehazard r<strong>at</strong>ing based on <strong>the</strong> fire hazards of<strong>the</strong> parcels th<strong>at</strong> were sampled within <strong>the</strong>neighborhoods. The point scoring system isfound in Table 1. The range of possiblescores is 9 – 80 or more, depending on <strong>the</strong>number of decks present.ResultsOverall fire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ingThe mean citywide fire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ing was 30(s.d. 6), due in large part to <strong>the</strong> city’sinfrastructure, including good access (wide,paved roads), <strong>the</strong> availability of w<strong>at</strong>er, and<strong>the</strong> presence of city and agency fire-fightingresources (Table 2). As expected, <strong>the</strong>Tahoe Keys exhibited <strong>the</strong> lowest firehazard, with a mean fire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ing of 24(s.d. 5), and <strong>the</strong> Heavenly Ski Area had <strong>the</strong>highest (38, s.d. 7). The r<strong>at</strong>ing for <strong>the</strong>remaining neighborhoods ranged from 28 to30.Lot sizeThe sampled lots in South Lake Tahoe weresmall. Mean lot size varied from 585 m 2 in<strong>the</strong> Sierra tract to 1211 m 2 in Heavenly. Thedifference in size is explained by <strong>the</strong>vari<strong>at</strong>ion in <strong>the</strong> depth of <strong>the</strong> lots r<strong>at</strong>her than<strong>the</strong>ir width. The mean lot width citywide was22 m (s.d. 8.5 m). The lot size in <strong>the</strong> Sierr<strong>at</strong>ract was significantly smaller than any o<strong>the</strong>rneighborhood in <strong>the</strong> city.5

Table 1. Point scoring system for risk factors.RISK FACTORIngress/egressPrimary road widthAccessibilitySCORING1- two or more primary road3- one road, primary route5- one way in/out1- >6.1m3- 15m3- outside radius 40%Wall m<strong>at</strong>erials+1 – wood sidingWall, eave, roof vents+2 – some present without _ in. mesh coverPredominant number of window panes+1 – predominantly single-panedDeck height +1 – each deck with height > 0.5mOpen space below deck+1 – each deck with open space bene<strong>at</strong>hStorage of flammable m<strong>at</strong>erials under deck +1 – each deck with storage of flammables bene<strong>at</strong>hDeck m<strong>at</strong>erials+1 – each wooden deckParcel sizeAdjustments made for small parcelsRel<strong>at</strong>ive maintenance1- parcel is worse than neighbors3- about <strong>the</strong> same5- neighbors are worse than parcel6

Table 2. <strong>Fire</strong> hazard r<strong>at</strong>ing, non-compliance r<strong>at</strong>es, and risk factors in South Lake Tahoe neighborhoods.Risk FactorCityNeighborhoodTotal(n=102)Keys(n=15)The Y(n=22)N. Central(n=13)Sierra(n=22)Bijou(n=21)Heavenly(n=9)Mean fire hazardr<strong>at</strong>ing (s.d.)30 (6) 24 (5) 30 (4) 30 (6) 30 (6) 28 (5) 38 (7)Maintenance noncompliancer<strong>at</strong>eIndividual def.space noncompliancer<strong>at</strong>eIndividual totalnon-compliancer<strong>at</strong>eIndividual def.space noncompliancer<strong>at</strong>e(adjusted forsmall parcels)Individual totalnon-compliancer<strong>at</strong>e (adjusted forsmall parcels)Irrig<strong>at</strong>ion (% ofparcels with lessthan half irrig<strong>at</strong>ed)Mean slope %(s.d.)Wood exterior (%of homes)Wood roof (% ofhomes)Window hazard(% of homes)Deck hazard (%of homes)66 20 68 69 73 76 8975 47 86 85 77 62 10053 7 59 62 64 48 8986 80 91 92 82 81 10057 20 59 62 64 58 8952 13 45 69 59 58 782 (6) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 1 (3) 0 (0) 15 (16)96 87 95 100 100 95 10031 27 18 54 27 29 5629 27 41 23 32 24 2267 60 68 77 73 48 89Compliance with PRC 4291Citywide, <strong>the</strong> majority of parcels hadincreased fire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ings because <strong>the</strong>ywere partially or wholly non-compliant withPRC 4291. Sixty-six percent of <strong>the</strong> sampledparcels were non-compliant with <strong>the</strong> law’srequirements for maintenance and 75%exhibited little or no defensible space. Intotal, 53% of <strong>the</strong> parcels were noncompliantfor both maintenance anddefensible space.When taking small parcel size intoconsider<strong>at</strong>ion, i.e. including <strong>the</strong> veget<strong>at</strong>ionof neighboring parcels in <strong>the</strong> defensiblespace analysis, 86% of <strong>the</strong> parcels werenon-compliant for defensible space and57% were non-compliant for bothmaintenance and defensible space.Adjusting <strong>the</strong> defensible space r<strong>at</strong>ing toaccount for neighboring lots had <strong>the</strong>gre<strong>at</strong>est effect on <strong>the</strong> defensible spacecompliance r<strong>at</strong>es for <strong>the</strong> Keys and for Bijou.Smaller changes were observed for <strong>the</strong> Y,

North Central, and Sierra. It had no effecton <strong>the</strong> 0% defensible space compliance r<strong>at</strong>efor Heavenly.Irrig<strong>at</strong>ionOver half <strong>the</strong> parcels citywide had irrig<strong>at</strong>ionon less than half of <strong>the</strong> veget<strong>at</strong>ion found on<strong>the</strong> parcel. The veget<strong>at</strong>ion in <strong>the</strong> Keys,which was domin<strong>at</strong>ed by turf grass andplanted exotics, was well irrig<strong>at</strong>ed, whileover 75% of <strong>the</strong> parcels in Heavenly, whichwere domin<strong>at</strong>ed by n<strong>at</strong>ive conifer stands,showed little evidence of irrig<strong>at</strong>ion. Lessthan one third of <strong>the</strong> parcels in <strong>the</strong> NorthCentral neighborhood were irrig<strong>at</strong>ed. From41% - 55% of <strong>the</strong> parcels in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rneighborhoods were irrig<strong>at</strong>ed.SlopeMost of <strong>the</strong> parcels th<strong>at</strong> were sampledexisted on little or no slope, with <strong>the</strong>exception of parcels in Heavenly, where <strong>the</strong>mean was 15% and <strong>the</strong> range was from 0%to 53%.Wall m<strong>at</strong>erialThe preferred building m<strong>at</strong>erial for homes inSouth Lake Tahoe was wood. 96% of <strong>the</strong>homes in <strong>the</strong> sample had exterior walls th<strong>at</strong>were shakes, logs, or wood siding. Thirteenpercent of <strong>the</strong> homes in <strong>the</strong> Keys werepredominantly brick, stucco, or stone, butfrom 95 – 100% of <strong>the</strong> homes in <strong>the</strong>remaining neighborhoods had woodexteriors.Roof m<strong>at</strong>erialCitywide, 31% of <strong>the</strong> sampled homes had asignificant increase in susceptibility toignition because of wood roofs.Neighborhoods where more than half <strong>the</strong>homes had wood roofs were North Central(54%) and Heavenly (56%). The fewestnumber were found in <strong>the</strong> neighborhood of<strong>the</strong> Y (18%).Window panesCitywide, 29% of <strong>the</strong> sampled homes hadincreased fire hazard due to <strong>the</strong> presence ofsingle-paned glass in over half <strong>the</strong> windowsof <strong>the</strong> home. The highest percentage ofhomes th<strong>at</strong> had predominantly single-panedwindows was in <strong>the</strong> neighborhood of <strong>the</strong> Y(41%), while <strong>the</strong> lowest was in Heavenly(22%).<strong>Hazard</strong>ous decks<strong>Hazard</strong>ous decks were found on 67% of <strong>the</strong>homes citywide. Deck construction andplacement was particularly problem<strong>at</strong>ic inHeavenly, where slopes were gre<strong>at</strong>est. Inth<strong>at</strong> neighborhood, eight of <strong>the</strong> nine parcelssampled had hazardous decks. In Bijou only48% of <strong>the</strong> homes had hazardous decks,while 60 – 73% of <strong>the</strong> homes in <strong>the</strong>remaining neighborhoods had hazardousdecks.DiscussionThe results of this study clearly indic<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong>standard city-scale fire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ing inSouth Lake Tahoe will not providemanagers and planners with sufficientlydetailed inform<strong>at</strong>ion to implement aneffective fire hazard mitig<strong>at</strong>ion program.While <strong>the</strong> city’s infrastructure is good,individual homeowners in <strong>the</strong> communityrarely choose for fire safety in terms ofconstruction m<strong>at</strong>erials, propertymaintenance, and landscaping or defensiblespace. The problem of non-compliance isworsened by <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> many of <strong>the</strong> city’slots are so small <strong>the</strong>y are influenced by <strong>the</strong>fire hazard of neighboring lots.Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, results indic<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> firehazard r<strong>at</strong>ing should be improved toaccount for <strong>the</strong> fire hazard cre<strong>at</strong>ed byneighboring veget<strong>at</strong>ion and houses in areasdomin<strong>at</strong>ed by small lots. Also, eachcomponent of a fire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ing systemshould produce results than can be used asdecision support for fire management,including identifying priority areas fortre<strong>at</strong>ment, identifying problem<strong>at</strong>ic areas in8

terms of non-compliance, and identifyingreasons for non-compliance. Each of <strong>the</strong> sixneighborhoods in South Lake Tahoe has aunique profile in terms of <strong>the</strong> suite of factorsth<strong>at</strong> contribute most significantly toneighborhood-scale fire hazard. Theneighborhood profiles can be used to directand focus management and homeownereduc<strong>at</strong>ion efforts. The obvious differencebetween <strong>the</strong> Keys and Heavenly, forexample, provides managers with a clearset of management objectives, but <strong>the</strong>re arealso important, less obvious differencesbetween <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r neighborhoods.For example, results indic<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Yhad an average fire hazard for <strong>the</strong> city, butcompared to <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> city thisneighborhood was characterized by a lowpercentage of wood roofs, better irrig<strong>at</strong>ion,average compliance with PRC 4291, and anaverage hazard cre<strong>at</strong>ed by decks.However, <strong>the</strong> fire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ing was <strong>the</strong>same as <strong>the</strong> citywide average because<strong>the</strong>se positive factors were offset by its 85%non-compliance r<strong>at</strong>e for defensible space.This figure increased to 91% when adjustedfor small lot size. Compared to Sierra, <strong>the</strong> Yhad a lower compliance r<strong>at</strong>e but r<strong>at</strong>ed betterin terms of construction m<strong>at</strong>erials anddecks. Compared to North Central, <strong>the</strong> Yexhibited comparable compliance r<strong>at</strong>es andwas slightly better in terms of deck hazards,but <strong>the</strong> Y r<strong>at</strong>ed far worse in terms of <strong>the</strong>percentage of wood roofs and single-panedwindows. These d<strong>at</strong>a can guidemanagement decisions, including both fuelsreduction programs and outreach andeduc<strong>at</strong>ion th<strong>at</strong> focus on <strong>the</strong> particular needsin each neighborhood.In addition to <strong>the</strong> educ<strong>at</strong>ion efforts th<strong>at</strong>focus on defensible space andmaintenance, <strong>the</strong>re is clearly a need toeduc<strong>at</strong>e residents about o<strong>the</strong>r practicesrel<strong>at</strong>ed to fire hazard. Educ<strong>at</strong>ion is neededin Heavenly and elsewhere about <strong>the</strong>benefits of irrig<strong>at</strong>ion in terms of fuelmoisture content and <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ionshipbetween drought stress, bug kill, and firehazard. Most homes already have doublepanedwindows for better insul<strong>at</strong>ion againstwinter we<strong>at</strong>her, but many residents do notrealize th<strong>at</strong> double-paned windows alsodecrease <strong>the</strong> risk of structural ignition.<strong>Hazard</strong>ous decks are a chronic problem inHeavenly, where most decks hang oversteep slopes covered with continuoussurface fuels. In this community, which ischaracterized by small lots and manyseasonal residents, educ<strong>at</strong>ion on <strong>the</strong>importance of neighborhood-scalecooper<strong>at</strong>ion is critical.In sum, standard fire hazard analysis inSouth Lake Tahoe and similar communitiesis likely to underestim<strong>at</strong>e individual firehazard. First, <strong>the</strong> city’s fire-safeinfrastructure is included in <strong>the</strong> parcel-scaleanalysis, which offsets <strong>the</strong> increasedindividual fire hazard associ<strong>at</strong>ed with a lackof defensible space and maintenancearound <strong>the</strong> home. Compliance with PRC4291 is perhaps <strong>the</strong> most important factor instructure survivability, but <strong>the</strong> influence of<strong>the</strong> city’s good infrastructure on its overallfire hazard r<strong>at</strong>ing obscures <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong>three-quarters of <strong>the</strong> parcels citywide arenon-compliant with defensible space codesand two-thirds are non-compliant withmaintenance codes. Second, <strong>the</strong> hazard onsmall lots will be fur<strong>the</strong>r underestim<strong>at</strong>edbecause of <strong>the</strong> influence of <strong>the</strong> fire hazardof neighboring parcels.A more appropri<strong>at</strong>e approach to fire hazardassessment in South Lake Tahoe is toassess parcels for compliance, lot size, and<strong>the</strong> individual choices homeowners make interms of construction m<strong>at</strong>erials andirrig<strong>at</strong>ion. Analysis of compliance r<strong>at</strong>es andhomeowner choices will provide a moreaccur<strong>at</strong>e estim<strong>at</strong>e of individual fire hazard.The analysis can also serve as decisionsupport for focusing outreach and educ<strong>at</strong>ionefforts and for prioritizing areas th<strong>at</strong> aremost in need of homeowner compliance andcooper<strong>at</strong>ion.9

AcknowledgementsThe author would like to thank SteveLennartz, Tommy Mouton, Nancy Strahan,Torry Ingram, Sabrina M<strong>at</strong>his, and StephanStreiling for <strong>the</strong>ir field work. Also, <strong>the</strong> LakeTahoe Basin Management Unit (USDAForest Service) and <strong>the</strong> CaliforniaDepartment of Forestry and <strong>Fire</strong> Protectionwere very helpful with <strong>the</strong>ir insights andsupport. Much appreci<strong>at</strong>ion also goes to Dr.E. Gregory McPherson (Project Leader,USDA Forest Service, Center for <strong>Urban</strong>Forest Research), to Dr. Madalene Ransom(St<strong>at</strong>e Economist, USDA N<strong>at</strong>ural ResourceConserv<strong>at</strong>ion Service), and to Scott Maco(<strong>Urban</strong> Forester, USDA Forest Service,Center for <strong>Urban</strong> Forest Research) forcomments on <strong>the</strong> early drafts of this report.This study was part of a project fundedthrough <strong>the</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional <strong>Fire</strong> Plan.Liter<strong>at</strong>ure CitedAbt, R. C., M. K. Kupyers and J. B. Whitson.1991. Perception of fire danger andwildland/urban policies after wildfire.USDA Forest Service. GTR SE-69, pp.257-259.Bailey, D. W. 1991. The wildland-urbaninterface: social and politicalimplic<strong>at</strong>ions in <strong>the</strong> 1990’s. <strong>Fire</strong>Management Notes 52(1): 11-18.Cohen, J. 1995. Structure Ignition<strong>Assessment</strong> Model (SIAM).USDAForest Service. PSW-GTR-158.Cortner, H. J. 1991. <strong>Interface</strong> policy offersopportunities and challenges: USDAForest Service str<strong>at</strong>egies andconstraints. Journal of Forestry 89(6):31-34.de Jong, L. 2002 (in review). <strong>Urban</strong>Forestry <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Wildland</strong><strong>Interface</strong>: Case Study in South LakeTahoe.Foote, E., R. Martin, J. K. Gilless. 1991. Thedefensible space factor study: asurvey instrument for post-firestructure loss analysis. Proceedings,11 th Conference on <strong>Fire</strong> and ForestMeteorology. Society of AmericanForesters. p. 66 – 73.Garrett, Brian. <strong>Urban</strong> Lot Manager, USDAForest Service Lake Tahoe BasinManagement Unit (LTBMU). May 7,2002.Harcourt, Steve. Area Forester, CaliforniaDepartment of Forestry and <strong>Fire</strong>Protection. Telephone convers<strong>at</strong>ion,February 11, 2002.Hodgson, R. W. 1993. Perceptions ofDefensible Space: PerceivedCharacteristics th<strong>at</strong> Influence<strong>Wildland</strong>-<strong>Urban</strong> Intermix Residents toAccept or Reject <strong>Fire</strong> SafeLandscaping. Prepared for <strong>the</strong>California Department of Forestry and<strong>Fire</strong> Protection.Manfredo, M. J., M. Fishbein, G.E. Haasand A.E. W<strong>at</strong>son. 1990. Attitudestoward prescribed fire policies.Journal of Forestry 88(7): 19–23.Manley, P. and M. Schlesinger. 2001. FinalReport for <strong>the</strong> California TahoeConservancy and US Forest Service.April, 2001.Murphy, D.D., C. M. Knopp, eds. 2000.Lake Tahoe w<strong>at</strong>ershed assessment:Volume I. Gen.Tech.Rep. PSW-GTR-175. Albany, CA: Pacific SouthwestResearch St<strong>at</strong>ion, Forest Service, U.S.Department of Agriculture; 736 pp.NFPA. 1997. NFPA-299: Standard forProtection of Life and Property from10

Wildfire. N<strong>at</strong>ional <strong>Fire</strong> ProtectionAssoci<strong>at</strong>ion. 17 pp.Quarles, S. 2001. Testing protocols andfire tests in support of performancebasedcodes. California’s 2001 WildfireConference, Oakland, CA. October 10-12, 2001.Quarles, S. 2002. Conflicting designissues in wood frame construction. 9 thDurability Building M<strong>at</strong>erials Conference,Brisbane, Australia. March 2002.Products. White Sulphur Springs, WV.January 24-27, 2000.Winter, G. and J. S. Fried. 2000.Homeowner Perspectives on <strong>Fire</strong><strong>Hazard</strong>, Responsibility, andManagement Str<strong>at</strong>egies <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Wildland</strong>-<strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Interface</strong>. Society &N<strong>at</strong>ural Resources, 13: 33-49.Skinner, C., C. Chang 1996. <strong>Fire</strong> regimes,past and present. In: Sierra NevadaEcosystem Project: Final Report toCongress, volume II, chapter 38. Davis,CA, University of California, Centers forW<strong>at</strong>er and <strong>Wildland</strong> Resources.Smith, E. and M. Rebori. 2001. Factorsaffecting property owner decisionsabout defensible space. In: ConferenceProceedings for Forestry Extension:Assisting Forest Owner, Farmer, andStakeholder Decision-Making.Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Union of Forestry ResearchOrganiz<strong>at</strong>ions, Lorne, Australia. October29 -November 2, 2001. p.404-408.Tran, H. C., J. Cohen, R. Chase. 1992.Modeling ignition of structures inwildland/urban interface fires.Proceedings, 1 st Intern<strong>at</strong>ional <strong>Fire</strong> andM<strong>at</strong>erials Conference. Arlington, VA. p.253 – 262.U. S. Environmental D<strong>at</strong>a Service. 2000.Clim<strong>at</strong>ological d<strong>at</strong>a analysis annualsummary: California.White, R. 2000. <strong>Wildland</strong>/urban interfacefire research <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> USDA ForestService, Forest Products Labor<strong>at</strong>ory:past, present and future. In:Proceedings of <strong>the</strong> Thirtieth Intern<strong>at</strong>ionalConference on <strong>Fire</strong> Safety, <strong>the</strong> TwelfthIntern<strong>at</strong>ional Conference on ThermalInsul<strong>at</strong>ion, <strong>the</strong> Fourth Intern<strong>at</strong>ionalConference on Electrical and Electronic11