PERSONALITY AND CAREER SUCCESS - Timothy A. Judge

PERSONALITY AND CAREER SUCCESS - Timothy A. Judge

PERSONALITY AND CAREER SUCCESS - Timothy A. Judge

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 6060–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUALDEFINITION OF <strong>CAREER</strong> <strong>SUCCESS</strong>Career success can be defined as the real or perceivedachievements individuals have accumulatedas a result of their work experiences (<strong>Judge</strong>,Cable, Boudreau, & Bretz, 1995). Most researchhas divided career success into extrinsic andintrinsic components (see also Khapova, Arthur,and Wilderom, Chapter 7; Guest and Sturges,Chapter 16). Extrinsic success is relativelyobjective and observable and typically consistsof highly tangible outcomes such as pay andascendancy (Jaskolka, Beyer, & Trice, 1985).Conversely, intrinsic success is defined as individuals’subjective appraisal of their success andis most commonly expressed in terms of job,career, or life satisfaction (Gattiker & Larwood,1988; <strong>Judge</strong> et al., 1995). Research confirms theidea that extrinsic and intrinsic career successcan be assessed as relatively independent outcomes,as they are only moderately correlated(<strong>Judge</strong> & Bretz, 1994).The three criteria most commonly used toindex extrinsic career success are (a) salary orincome, (b) ascendancy or number of promotions,and (c) occupational status. The last factoris perhaps the most intriguing. Occupational statuscan be viewed as a reflection of societal perceptionsof the power and authority afforded bythe job (Blaikie, 1977; Schooler & Schoenbach,1994). Occupational status has long been studiedin sociology as a measure of occupationalstratification (the sorting of individuals intooccupations of differential power and prestige).Sociologists have gone so far as to conclude thatoccupational status measures “reflect the classicalsociological hypothesis that occupationalstatus constitutes the single most importantdimension in social interaction” (Ganzeboom &Treiman, 1996, p. 203) and to term occupationalstatus as sociology’s “great empirical invariant”(Featherman, Jones, & Hauser, 1975, p. 331).The required educational skills, the potentialextrinsic rewards offered by the occupation, andthe ability to contribute to society through workperformance are the most important contributorsto occupational status (Blaikie, 1977). As aresult, sociologists often view occupationalstatus as the most important sign of success incontemporary society (Korman, Mahler, &Omran, 1983). Viewed from this perspective,occupational status indicates extrinsic successbecause of its prestige and because it conveysincreased job-related responsibilities andrewards (Poole, Langan-Fox, & Omodei, 1993).Intrinsic career success is measured in severaldistinct ways. The most common marker forintrinsic career success is a subjective rating ofone’s satisfaction with one’s career. Items thatfit under the career satisfaction umbrella askrespondents to directly indicate how they feelabout their careers in general, whether theybelieve that they have accomplished the thingsthat they want to in their careers or if theybelieve that their future prospects in theircareers are good (e.g., Boudreau, Boswell, &<strong>Judge</strong>, 2001; <strong>Judge</strong>, Higgins, Thoresen, &Barrick, 1999; Seibert & Kraimer, 2001). Jobsatisfaction is often closely related to careersatisfaction, but there are some important differences.Particularly, job satisfaction usually isdirected around one’s immediate emotionalreactions to one’s current job, whereas careersatisfaction is a broader reflection of one’s satisfactionwith both past and future work historytaken as a whole.FIVE-FACTOR MODELConsensus is emerging that an FFM (or the “BigFive”) of personality can be used to describe themost salient aspects of personality (Goldberg,1990). The first researchers to replicate the fivefactorstructure were Norman (1963) and Tupesand Christal (1961), both of whom are generallycredited with founding the FFM. The five-factorstructure has been recaptured through analysesof trait adjectives in various languages, factoranalytic studies of existing personality inventories,and decisions regarding the dimensionalityof existing measures made by expert judges(McCrae & John, 1992). The cross-cultural generalizabilityof the five-factor structure has beenestablished through research in many countries(McCrae & Costa, 1997). Evidence indicatesthat the Big Five are substantially heritable(roughly 50% of the variability in the Big Fivetraits appears to be inherited) and stable overtime (Costa & McCrae, 1988; Digman, 1989).The dimensions comprising the FFM areemotional stability, extroversion, openness to

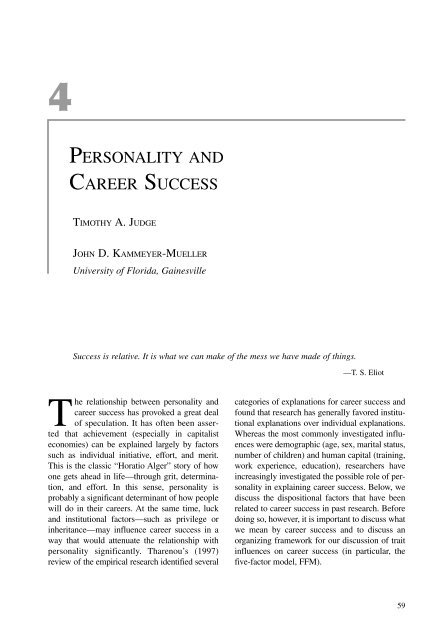

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 61Personality and Career Success–•–61experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.Emotional stability represents the tendencyto exhibit positive emotional adjustment andseldom experience negative affects (NAs) suchas anxiety, insecurity, and hostility. Extroversionrepresents the tendency to be sociable, assertive,and active and to experience positive affectssuch as energy and zeal. Openness to experienceis the disposition to be imaginative, nonconforming,unconventional, and autonomous.Agreeableness is the tendency to be trusting,compliant, caring, and gentle. Conscientiousnesscomprises two related facets, achievement anddependability. The Big Five traits have beenfound to be relevant to many aspects of life,such as interpersonal relations (e.g., Pincus,Gurtman, & Ruiz, 1998) and even longevity(Friedman et al., 1995). As we will see, thesetraits are also relevant to several aspects ofcareer success. We will also discuss other personalitytraits that might be relevant for careersuccess where relevant research exists.WHY DOES <strong>PERSONALITY</strong> AFFECT<strong>CAREER</strong> <strong>SUCCESS</strong>? A PROPOSED MODELStarting from the premise that personality canbe related to numerous work-relevant outcomes,it is worth considering how personality traitsmight have an effect on careers. To this end, wepropose that Figure 4.1 depicts the most importantand empirically supported linkages betweenpersonality and career-relevant outcomes thatwill be reviewed in this chapter. We first proposethat personality leads individuals to possesscertain jobs both through the process ofattraction to the jobs of interest as well as byleading organizations to select certain individuals.Personality also influences individualperformance on the job in a way that will lead tohigher compensation, new job responsibilities,and promotions into higher organizationalranks. Finally, personality influences the waysin which individuals engage in social interactionsat work. Social interactions can lead to anynumber of outcomes, ranging from improvedknowledge of the job and role to more visibilityin the organization. These factors combine, inturn, to predict the job features individualsencounter on the job, including both extrinsicand intrinsic features known to predict jobsatisfaction. The static nature of this model is asimplification, because it is likely that therewould be multiple nonrecursive links (e.g., overtime, job features affect social behavior, careersuccess affects job features), but we present thissimplified model because there is not sufficientresearch to discuss these reciprocal relationshipsat the present time and our model is basedon extant empirical results. To demonstratethe relevance of this model, it is first necessaryto determine if there is in fact a relationshipbetween personality and career success toexplain in the first place. This topic is thesubject of the next section.FIVE-FACTOR MODEL <strong>AND</strong><strong>CAREER</strong> <strong>SUCCESS</strong>Below, we review the literature on the relationshipof the Big Five to aggregate career success,with our review organized according to each ofthe Big Five traits. Within each trait, we firstdiscuss the link between the trait and intrinsicsuccess, followed by a discussion of the linkbetween the trait and extrinsic success.ConscientiousnessIn general, conscientiousness is positivelycorrelated with measures of intrinsic career success,though the multivariate evidence is far lessconsistent. Meta-analytic evidence indicatesthat conscientiousness is positively associatedwith job (ρˆ = .26; <strong>Judge</strong>, Heller, & Mount,2002) and life (rˆu = .21; DeNeve & Cooper,1998) satisfaction. 1 <strong>Judge</strong> et al. (1999) foundthat conscientiousness strongly predicted intrinsicsuccess (βˆ = .34, p < .01), even when personalitywas measured during childhood and thelatter variables were measured in midadulthood.On the other hand, several studies have foundlimited incremental validity of conscientiousnessin predicting career success with a multivariatedesign. Representative findings includenonsignificant relationships of βˆ = .06 (Seibert& Kraimer, 2001) and βˆ = .09 (Bozionelos,2004) or small but significant effects of βˆ = –.05among American executives and βˆ = .10 amongEuropean executives (Boudreau et al., 2001).

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 62Jobs HeldJob choiceAttractiveness to employersPersonalityConscientiousnessExtroversionAgreeablenessEmotional stabilityOpenness to experienceOther traitsSocial Behavior Job Features Career SuccessRelationship buildingConsiderationJob rewardsObjective characteristicsSubjective characteristicsObjectiveSubjectiveJob PerformanceTask performanceCitizenshipDevianceFigure 4.1 Conceptual Model of Personality and Career Success62

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 6464–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUALitself in positive moods, greater social activity,and more rewarding interpersonal experiences.Meta-analytic evidence indicates that extrovertsreport higher levels of job (<strong>Judge</strong> et al., 2002:ρˆ = .25) and life (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998:rˆu = .17) satisfaction. Boudreau et al. (2001)found that both American and European extrovertsreported higher levels of career satisfaction(βˆA = .10 and βˆE = .15, respectively). Seibert andKraimer (2001) found that extroversion positivelypredicted career satisfaction (βˆ = .15,p < .01). In <strong>Judge</strong> et al. (1999), extroversionfailed to predict intrinsic career success (βˆ = .00,ns). Bozionelos (2004) found that extroversionfailed to predict subjective career success(βˆ = .03, ns). Thus, in general, it appears thatextroversion is positively related to intrinsiccareer success, though the results are not fullyconsistent.Extroversion and its facets appear to be positivelyrelated to extrinsic career success. Rawlsand Rawls (1968) found that measures of dominanceand sociability differentiated successfuland unsuccessful executives when pay and jobtitle were considered as indices of success.Extroversion was also predictive of salary andjob level in two recent studies conducted inthe United Kingdom (Melamed, 1996a, 1996b).Well-controlled longitudinal studies alsohave supported a link between extroversion andextrinsic success. For example, Caspi, Elder,and Bem (1988) found that childhood ratingsof shyness were negatively associated withadult occupational status (βˆ = –.29, p < .01).Likewise, Howard and Bray (1994) noted thatdominance (a characteristic of extroverts,Watson & Clark, 1997) was correlated (rˆ = .28,p < .01) with managerial advancement. Harrelland Alpert (1989) found that sociability waspositively, though not strongly, correlated withearnings 20 years after the trait was measured(rˆ = .14, p < .05). Seibert and Kraimer (2001)found that extroversion positively predictedearnings and promotions (βˆ = .13 in both cases,p < .01). Melamed (1996a) found that extroversionwas positively correlated with relativewages (rˆ = .25, p < .01) and managerial level(rˆ = .15 p < .05) for men but not for women(rˆ = .07, ns and rˆ = .09, ns, respectively). InBozionelos (2004), extroversion failed to predictobjective career success (βˆ = .07, ns).Thus, extroversion tends to be positivelyrelated to intrinsic as well as extrinsic careersuccess. The results are not totally consistent, asone would expect based on data from multiplesamples. However, the majority of the evidencesuggests that extroverts are more extrinsicallysuccessful in their careers and more satisfiedwith them as well.Openness to ExperienceOpenness displays an inconsistent relationshipwith career success. Judging from the metaanalyticevidence, the association of opennesswith job satisfaction (ρˆ = .02, <strong>Judge</strong> et al., 2002)is weak and variable. These results are matchedby explicit studies of career success. For example,Boudreau et al. (2001) found that openness failedto predict any aspect of intrinsic success, with theexception of a significant but small effect on jobsatisfaction (βˆ = –.07, p < .01) for Europeanexecutives. <strong>Judge</strong> et al. (1999) found that childhoodopenness was positively correlated withadult intrinsic success (rˆ = .21, p < .05), but thateffect became nonsignificant (βˆ = .12, ns) oncethe influence of the other Big Five traits and intelligence(which correlated rˆ = .51 with openness)was taken into account. Bozionelos (2004) foundthat openness failed to predict subjective careersuccess (βˆ = .03, ns). Seibert and Kraimer (2001)found that openness was unrelated to career satisfaction(βˆ = .02, ns).In terms of extrinsic success, the resultsare equally inconsistent. Boudreau et al. (2001)found that openness failed to significantly predictany aspect of career success for Americanor European executives. As with the results forintrinsic career success, <strong>Judge</strong> et al. (1999)found that childhood openness was positivelycorrelated with adult extrinsic success (rˆ = .26,p < .05), but this effect disappeared (βˆ = –.02,ns) once the influence of the other Big Fivetraits and intelligence was taken into account.Seibert and Kraimer (2001) found that opennessnegatively predicted earnings (βˆ = –.10, p < .01)and was unrelated to number of promotions(βˆ = –.01, ns). Bozionelos (2004) found thatopenness negatively predicted objective careersuccess (βˆ = –.15, p < .05). Thus, it appears thatopenness bears little consistent relationship withintrinsic or extrinsic career success.

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 65Personality and Career Success–•–65AgreeablenessEvidence tends to indicate a relatively modestbut positive relationship between agreeablenessand job satisfaction (ρˆ = .17, <strong>Judge</strong> et al.,2002). However, the relationship appears to disappearonce adjusted for the influence of theother Big Five traits. Both <strong>Judge</strong> et al. (1999) andBoudreau et al. (2001) found that agreeablenesswas unrelated to any measure of intrinsic careersuccess. Seibert and Kraimer (2001) found thatagreeableness negatively predicted career satisfaction,though the effect size was rather small(βˆ = –.09 p < .05). Conversely, Bozionelos (2004)found that agreeableness positively predicted subjectivecareer success (βˆ = .18, p < .05).What is more intriguing is that agreeablenessappears to be negatively related to extrinsic careersuccess. <strong>Judge</strong> et al. (1999) found that agreeablenesswas relatively strongly negatively predictiveof extrinsic career success (βˆ = –.32, p < .01), andBoudreau et al. (2001) found that agreeablenessnegatively predicted all aspects (salary, promotions,job level) for both American and Europeanexecutives, though the effect sizes were appreciablysmaller (e.g., βˆ = –.14, p < .01 for Americanexecutives’ salary). On the other hand, Seibert andKraimer (2001) found that agreeableness didnot predict salary (βˆ = –.03, ns) or promotions(βˆ = .00, ns). Bozionelos (2004) found that agreeablenessnegatively predicted objective careersuccess (βˆ = –.13, p < .05), which is odd, giventhat he found agreeable people more intrinsicallysuccessful. Thus, it appears that agreeableness isunrelated to intrinsic career success but negativelyrelated to extrinsic career success.OTHER DISPOSITIONAL TRAITSThe FFM does not exhaust the traits that maybe relevant to career success. Below, we reviewevidence on the relationship of other traits tocareer success.Proactive PersonalityTwo studies have suggested that proactivepersonality—the tendency to identify and act onopportunities, take the initiative, and persevere—is positively associated with career success.Seibert, Crant, and Kraimer (1999) found thatproactive personality positively predicted earnings(βˆ = .11, p < .05), number of promotions(βˆ = .12, p < .05), and career satisfaction (βˆ = .30,p < .05). Seibert, Kraimer, and Crant (2001)found that proactive personality was related tocareer satisfaction (rˆ = .27, p < .01) but wasuncorrelated with salary progression (rˆ = .11, ns)or promotions (rˆ = .05, ns). A limitation of theseresults is that the FFM personality traits were notcontrolled, which is especially problematic giventhe existence of studies showing significant relationshipsbetween proactivity and both extroversionand conscientiousness (Crant, 1995).Agentic and Communal OrientationAbele (2003), studying approximately 800graduates from a large German university, foundthat agentic tendencies (“very self-confident,”“can make decisions easily,” “very active,” “veryindependent”) positively predicted objectivecareer success (βˆ = .15, p < .001) and subjectivecareer success (βˆ = .27, p < .001), which wasassessed with a single-item question (“Comparingyour occupational development until now withyour former student colleagues, how successfuldo you think you are?”). Abele (2003) furtherfound that communal tendencies (“very kind,”“very helpful to others,” “very emotional,” “ableto devote self completely to others,” “very warmin relation to others,” “very understanding, awareof feelings of others,” “very gentle”) failed to predicteither objective (βˆ = –.01, ns) or subjective(βˆ = –.01, ns) success. Surprisingly, given thestrong conceptual linkages between agentic andcommunal tendencies and the FFM, Abele didnot investigate the incremental validities of theseorientations beyond the FFM.Core Self-EvaluationsCore self-evaluations (CSEs) are a relativelyrecent addition to the personality literature.CSEs are a set of closely linked traits that includeemotional stability, an internal locus of control,self-esteem, and self-efficacy. Those higher inCSEs tend to appraise situations more positively,have higher levels of motivation, and havegreater confidence in their ability to positivelyinfluence the world around them (<strong>Judge</strong>, Locke,

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 6666–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUAL& Durham, 1997). We are aware of no researchthat has explicitly linked CSEs to career success.However, beyond the emotional stability evidencereviewed above, evidence has linked theother core traits to career success. Wallace(2001) found that internal locus of control positivelypredicted the career satisfaction (βˆ = .15,p < .01) and self-reported promotional opportunities(βˆ = .17, p < .05) of female lawyers butdid not significantly (negatively) predict theirearnings (βˆ = –.09, ns). Turban and Dougherty(1994) found that external locus of control wasnegatively associated with perceived career success(rˆ = .38, p < .05) and self-reported promotions(rˆ = .16, p < .05) but uncorrelated withsalary (rˆ = .00, ns). They also found that selfesteemwas uncorrelated with promotions(rˆ = .09, ns) or salary (rˆ = .10, ns) but was positivelycorrelated with perceived success (rˆ = .43,p < .05). Melamed (1996a) found that selfconfidencenegatively predicted job level forwomen (βˆ = –.21, p < .05) but not for men(βˆ = .13, ns); in another sample, self-confidencewas positively related to salary and job level forthe sample overall (rˆ = .16, p < .05 for both), butthe correlations were only significant for men. Ininterpreting these results, there are causalityissues. Because CSEs may be somewhat moremalleable than most traits (Bono & <strong>Judge</strong>,2003), it is possible that career success causesone to have a positive self-concept.SUMMARY OF PAST RESEARCHWhile reflecting on the results from pastresearch relating personality to career success,several themes emerge. First, the effect sizes arenot strong. The modal validities of personality inpredicting intrinsic and extrinsic success tend tobe in the 20s. In a sense, we have known this forsome time (Guion & Gottier, 1965). As Schmitt(2004) recently commented, “The observedvalidity of personality measures, then and now,is quite low even though they can account forincrementally useful levels of variance in workrelatedcriteria” (p. 348). Mischief is createdwhen we try to make the validities somethingthat they are not. At the same time, thinking interms of the other dichotomy—that validities aremeaningless—is equally misleading.Second, the results for each trait are notparticularly consistent. For every trait, there ismore than one weak and/or nonsignificant finding.Clearly, there are studies that would seem todisconfirm the hypothesis that a particular traitis predictive of career success. At the same time,with such qualitative reviews, it is very easy tooverinterpret the variability in the estimates(Hunter & Schmidt, 1990). We selected studiesthat were as representative of the current stateof the field as possible, with an emphasis onmethodologically rigorous studies conductedwith large samples, being careful to representthe diversity of findings currently available.Thus, one should realize that a comprehensivemeta-analysis would have illustrated thetrend toward results demonstrating fairly weak tomoderate, but consistent, relationships betweenpersonality and career success. Although this wasnot the purpose of this chapter, such a reviewwould be worthwhile, indeed necessary, to mostproperly interpret the findings.Third, despite the first two points, sometrends still emerge. Conscientiousness andextroversion tend to have very weak to positiveeffects on intrinsic and extrinsic career success.Emotional stability tends to have very weakpositive effects on intrinsic and extrinsic success.Agreeableness tends to have very weak tonegative effects on extrinsic success and verylittle effect on intrinsic success. Openness tendsto be unrelated to either component of careersuccess. Thus, if one wished to have a careerthat was deemed successful by conventionalstandards, one might wish to be conscientious,extroverted, emotionally stable, and perhaps nottoo agreeable. It would be hard to argue that onewould wish to be low in conscientiousness, forexample, in order to be successful.MEDIATORS OF THE <strong>PERSONALITY</strong>/<strong>CAREER</strong>-<strong>SUCCESS</strong> RELATIONSHIPGiven the evidence that personality is at leastsometimes related to career success, it is worthconsidering why personality traits might lead tosuperior career outcomes. We proposed earlierthat Figure 4.1 depicts the most important andempirically supported linkages between personalityand career-relevant outcomes. It will

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 67Personality and Career Success–•–67become clear in this section that these relationshipsare necessarily tenuous because of theconceptual distance from personality as aninternal trait to final measures of career success.The stages of the mediating model considerednext are as follows: (a) personality leads individualsto possess certain jobs, (b) personalityalso influences individual performance on thejob, and (c) personality influences the ways inwhich individuals engage in social interactionsat work. These factors are proposed to combineto predict the extrinsic and intrinsic featuresknown to predict job and career satisfaction.Personality and Jobs HeldOne mechanism that might lead to a relationshipbetween personality and career success isthe effect of personality on the types of jobsthat individuals might acquire. These relationshipscan be broadly divided into the effectsof personality on job preferences and the waysin which personality can lead an individual tobe considered desirable by employers. In otherwords, personality can influence what you wantas well as what you can get.The dominant paradigm in the literature onpersonality and job preferences comes fromthe long-established program of research on therealistic-investigative-artistic-social-enterprisingconventional(RIASEC) circumplex (see Savickas,Chapter 5; Kidd, Chapter 6; for a review of theresearch conducted over the past 40 years, seeHolland, 1997). The basic proposition of theRIASEC model is that there are stable individualdifferences in preferences for job characteristicsand that individuals who are in jobs that matchtheir preferences will be more satisfied. AlthoughRIASEC types are fairly stable over time (e.g.,Lubinski, Benbow, & Ryan, 1995), they are partiallydistinct from other measures of personality.Openness to experience correlates fairly stronglywith the artistic type (ρˆ = .39) and the investigativetype (ρˆ = . 21), and extroversion correlatesfairly strongly with the enterprising type (ρˆ = .41)and the social type (ρˆ = .25) (Barrick, Mount,& Gupta, 2003). The relationships between conscientiousness,agreeableness, and emotionalstability with any of the RIASEC dimensionsare more tenuous. There is also evidencethat the RIASEC dimensions add incrementalvariance in predicting jobs after FFM traitsare considered. For example, while RIASECdimensions rated at graduation were consistentlypredictive of employment in commensurate jobs(e.g., realistic individuals tend to hold jobshigher in realism) 1 year later, the five-factor personalitymodel provided almost no incrementalexplanatory power for most job characteristicsafter RIASEC was considered (De Fruyt &Mervielde, 1999).The relationship between personality traitsand success in the selection process has beenexplored in several studies. As will be shownlater, personality has been related to job performance,so it makes sense that employers mightwell prefer certain “types” of individuals basedon their impressions of who will do best on thejob. In a study examining interviewers’ perceptionsof applicants’ “fit” with their organization,the two most predictive variables after generalemployability was factored out were interpersonalbehaviors such as listening and warmth(βˆ = .44) and goal orientation characteristics,such as having goals and plans (βˆ = .26) (Rynes& Gerhart, 1990). Interviewers also perceivethat conscientiousness is a significant predictorof hirability across multiple job types (βˆ = .40)and that counterproductive behavior can be predictedby emotional stability (βˆ = –.36), conscientiousness(βˆ = –.25), and agreeableness(βˆ = –.24) (Dunn, Mount, Barrick, & Ones,1995). Not all interview types are equallyaffected by personality traits. Some research hassuggested that success in situational interviewsis less related to extroversion (rˆ = .01) than successin behavioral interviews (rˆ = .30) (Huffcutt,Weekley, Wiesner, Degroot, & Jones, 2001).Another reason why personality might influenceinterview success is because of the behaviorsassociated with different personality traits.An increasing number of studies have suggestedthat impression management is an importantcomponent of interview success. Kristof-Brown,Barrick, and Franke (2002) found that extrovertsengage in more self-promotion behavior (βˆ = .47)and that self-promotion behavior, in turn, wasassociated with perceptions of fit between theapplicant and the job (βˆ = .60). Agreeablenesswas associated with nonverbal cues (βˆ = .31),which were related to perceptions of similaritybetween the interviewer and interviewee (βˆ = .37).

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 6868–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUALGiven the meta-analytic evidence suggestingthat impression management is, at best, weaklyrelated to job performance (ρˆ = .04), it appearsthat the tendency for interviewers to favor theextroverted and, in particular, the immodestextroverted is an error in judgment (Viswesvaran,Ones, & Hough, 2001).The results to date suggest that conscientiousnessand extroversion are the dimensions ofpersonality that are most related to success inthe screening process. This is interesting in lightof the generally positive relationships betweenthese personality traits and career success.Research also suggests that interviewers deliberatelytry to select conscientious individuals inthe hope of obtaining better performance onthe job, whereas extroverts are able to improvetheir success through social influence. As wewill see, the linkage of extroversion with socialbehavior and conscientiousness with performanceappears in other areas as well.Personality and Job PerformanceThe relationship between personality andjob performance has received a huge amount ofattention. Seminal meta-analyses demonstratedthat there were consistent relationships betweenthe trait of conscientiousness and job performanceacross a number of jobs, while otherpersonality traits were not associated with performance(Barrick & Mount, 1991). Subsequentstudies have generally confirmed this resultwhen more specific measures of the FFMare used (Hurtz & Donovan, 2000); when specificoccupations such as sales are examined(Vinchur, Schippmann, Switzer, & Roth, 1998);when data are collected exclusively among theEuropean community (Salgado, 1997); or whenspecific dimensions of performance, such as citizenshipperformance (Borman, Penner, Allen,& Motowidlo, 2001), or counterproductivity(Salgado, 2002) are the focus. More recentresearch has shown that the trait of CSEs is alsorelated to job performance (correlations rangefrom r = .23 to r = .27) and, moreover, that thistrait shows incremental validity in predictingjob performance beyond the FFM of personality(<strong>Judge</strong>, Erez, & Bono, 2003).A study of 91 sales representatives demonstratedthat conscientiousness leads employeesto set goals (βˆ = .44) and to be more committedto these goals (βˆ = .35) (Barrick, Mount, &Strauss, 1993). Goal setting was related to salesvolume (βˆ = .21) and performance ratings(βˆ = .33), and goal commitment was related tosales volume (βˆ = .17) and performance ratings(βˆ = .16). An alternative, but conceptuallyrelated, model of personality and performancewas examined in a study of 164 sales agents(Barrick, Stewart, & Piotrowski, 2002). In thisstudy, conscientiousness was related to accomplishmentstriving (βˆ = .48) and extroversionwas related to status striving (βˆ = .39); accomplishmentstriving was related to status striving(βˆ = .45), which was related to job performance(βˆ = .41). Fewer data directly address the mediatingrelationship between conscientiousnessand other aspects of performance. In a sampleof 4,362 soldiers, dependability was relatedto fewer disciplinary actions (βˆ = –.23), whichwas in turn related to job performance (βˆ = –.27)(Borman, White, Pulakos, & Oppler, 1991).More research examining other dimensions ofpersonality as predictors of other dimensions ofperformance is clearly needed.Research on CSEs has examined mediatedmodels. Evidence, from both lab and field settingsfurther suggests that the effect of CSEs onjob performance can be explained by task motivationand goal-setting behavior (Erez & <strong>Judge</strong>,2001). In the lab study, the substantial effect ofCSEs on task performance (βˆ = .35) droppedconsiderably (βˆ = .18) after the relationshipbetween CSEs and motivation (βˆ = .41) wastaken into account by regressing performanceon motivation (βˆ = .44). In the field study, thetotal effect of CSEs on job performance(βˆ = .27) was 44% mediated by a path fromCSEs to goal setting (βˆ = .70) to activity level(βˆ = .30) and from activity level to sales performance(βˆ = .57).The literature on employee proactivity hasalso explored mediating models. A longitudinalstudy of 180 employees involving bothself-reports and supervisor reports showedthat proactive personality is positively relatedto innovation (βˆ = .18) and career initiative(βˆ = .32), which in turn were related to salarygrowth, promotions, and subjective career satisfaction(regression coefficients for the mediatorspredicting these outcomes were in the range

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 69Personality and Career Success–•–69from βˆ = .17 to βˆ = .36) (Seibert, Kraimer, &Crant, 2001).In light of these results, the effects showingthat conscientiousness, CSEs, and proactivityare related to extrinsic and intrinsic career successappear to occur at least partially throughthe mediating influence of improved motivationand task performance. Conscientiousness alsoappears to affect career success by producinglower deviance.Personality and Social TiesThe established paradigms proposing thatcareer success is largely a matter of individualinitiative, choice, and effort on the job have beensupplemented more recently by research demonstratingthat careers are made by social ties aswell. Research has shown that individuals withsuperior positions in social networks are ableto achieve superior work outcomes, includingaccess to information, access to resources, andcareer sponsorship (Seibert, Kraimer, & Liden,2001). This study showed that career successwas greater among individuals who fill a “structuralhole,” meaning that they were a crucialintermediary between groups of individuals whootherwise have little contact. The core variablesthat are studied in the social domain of personalityat work include measures of relationshipbuilding, knowledge of the political domain ofthe organization, and efforts to actively understandwhich behaviors are rewarded.A longitudinal study of the FFM of personalityand proactive adjustment among organizationalnewcomers found that extroversionwas significantly related to seeking feedback(βˆ = .18) and building relationships with colleagues(βˆ = .23), while openness to experiencewas related to feedback seeking (βˆ = .16)(Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). Relationshipbuilding was related, in turn, to social integration(βˆ = .20), role clarity (βˆ = .20), and jobsatisfaction (βˆ = .18) and negatively related tointention to turnover (βˆ = –.24), while feedbackseeking was positively related to job satisfaction(βˆ = .20) and negatively related to turnover(logistic regression coefficient = −.19).Proactive personality has also been investigatedin this domain. One study involving 180employees found that proactive personality wassignificantly related to political knowledge(βˆ = .28) and career initiative on the job(βˆ = .32), both of which were positively relatedto subsequent salary progression (βˆ = .17andβˆ = .25, respectively) and subjective perceptionsof career satisfaction (βˆ = .25and βˆ = .36, respectively)(Seibert, Kraimer, & Crant, 2001). A longitudinalexamination involving organizationalnewcomers found that proactivity was associatedwith greater role clarity (βˆ = .33), work groupintegration (βˆ = .13), and political knowledge(βˆ = .13) (Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003).Commitment was found to be higher among thosewith greater role clarity (βˆ = .17) and work groupintegration (βˆ = .23), but political knowledgewas not significantly related to any markers ofnewcomer adjustment. A longitudinal study ofnewcomer adjustment among doctoral studentsalso found that proactivity was positively relatedto building social relationships with coworkers(βˆ = .18) and positively associated with averagelevels of role clarity (βˆ = .40) and social integration(βˆ = .19) over the four time periods of thestudy (Chan & Schmitt, 2000).The relationship between lower-level employeesand more experienced, powerful membersof an organization (i.e., mentoring) has been ofsignificant interest in the careers literature. Someresearch suggests that protégés have an importantrole in initiating relationships. Initiation of relationshipswas positively related to internal locusof control (βˆ = .37), self-monitoring (βˆ = .43),and emotional stability (βˆ = .26); initiation waspositively related to having mentoring relationships(βˆ = .86), and these mentoring relationshipswere positively related to career attainmentand perceived career success (βˆ = .30) (Turban &Dougherty, 1994). Research in a similar straininvolving 184 early-career-stage Hong KongChinese has shown that extroversion leads toprotégé-initiated mentoring relationships (βˆ = .22)(Aryee, Lo, & Kang, 1999). Unfortunately,because of the correlational nature of these studies,it is difficult to assess causality in any meaningfulway. Some studies have suggested, usingessentially the same methodology, that havinga mentor can increase self-esteem, need forachievement, and need for dominance (Fagenson-Eland & Baugh, 2001).In sum, the research suggests that individualswho are extroverted are likely to have positive

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 7070–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUALsocial relationships, which may again serve as apotential mediator of extroversion and careersuccess. Proactivity’s effect on career successmay also be explained by social relationships.Given the close relationship between extroversionand proactivity, future research shouldattempt to examine whether one of these variablesis the more immediate explanation forcareer success through social connections.<strong>PERSONALITY</strong> <strong>AND</strong> JOB FEATURESResearchers have long proposed that there is animportant relationship between personality andjob features. An obvious area for considerationhere is the research on person-environment fit byHolland, described earlier. However, while theRIASEC theory primarily offers propositionsregarding how personality might relate to occupationalpreferences, there are additional reasonswhy personality might relate to both objectivejobs held as well as perceptions of jobs.One of the most controversial areas forresearch in the study of personality at work is therole of negative affectivity or neuroticism in perceptionsof job characteristics. The argumentsboil down to a dispute as to the role of dispositionalNA in measures of job characteristicsand work reactions. One of the first salvos fired inthis battle came when Watson, Pennebaker, andFolger (1986) noted that individuals with highlevels of dispositional NA will tend to view theirenvironments in negative terms and also reportdistress, dissatisfaction, and negative emotions.From the perspective of our model, this impliesthat personality shapes the subjective perceptionof job characteristics, which in turn leads to lowercareer satisfaction. The possibility that dispositionalNA can account for both perceptions of ajob as well as negative reactions to the job wasshown by Brief, Burke, George, Robinson, andWebster (1988), who found that there were significantrelationships between NA and job stress(rˆ = .34) and NA and job strain (rˆ = .57.) and thatthe substantial zero-order relationship betweenstress and strain (rˆ = .37) was reduced (rˆp = .22)after partialling out NA; relationships between jobstress and some other correlates fell even moreafter accounting for NA. From another angle,research has shown that even after subjectivelyrated job characteristics have been partialled out,NA is still negatively related to job satisfaction(βˆ = –.18) (Levin & Stokes, 1989). Anothermethod for factoring out personality as a selectionmechanism into certain types of work is by usingexperiments to randomly assign individuals toworking condition. Evidence from laboratorystudies generally suggests that individuals high inNA are more likely to see the same tasks morenegatively than individuals who are lower in NA(Levin & Stokes, 1989).An alternative point of view has been proposedby Spector and colleagues, who proposethat the relationship between NA and objectivejob characteristics is a substantial and importantone. Burke, Brief, and George (1993) alsonote that there is a possibility of causal andsubstantive effects involving dispositionalNA, job characteristics, and work attitudes.Evidence from Spector, Jex, and Chen (1995)found that incumbents’ self-reported negativeaffectivity was significantly correlated withexpert raters’ opinions of these individuals’ jobautonomy (rˆ = –.14), variety (rˆ = –.19), identity(rˆ = –.10), and complexity (rˆ = .17).Because the reports of job conditions are takenfrom significant others, this is fairly good evidencethat individuals who are higher in negativeaffectivity do tend to be in jobs that haveworse characteristics. This perspective alsoserves as a reminder that care must be takenbefore researchers assume that a relationshipbetween personality and work-related affectnecessarily is the result of perceptions beingshaped by situations; it is also possible that oneof the reasons people higher in negative affectivityare less satisfied at work is because theyare in more negative work situations.Research has also shown that employee perceptionsof appropriate emotional displays atwork are predicted based on employee extroversionand neuroticism, with extroversion beingrelated to perceptions that jobs demand morepositive emotional displays (βˆ = .20) and neuroticismbeing related to perceptions that jobsdemand more suppression of negative emotionaldisplays (βˆ = .15) (Diefendorff & Richard,2003). The study also showed that perceptionsof demands for positive emotional displays wereassociated with higher job satisfaction (βˆ = .39),while perceptions of demands for suppression

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 71Personality and Career Success–•–71of negative emotional displays were associatedwith lower job satisfaction (βˆ = –.22).There is evidence beyond simple negativeaffectivity related to job characteristics. Therelationship between CSEs measured in childhoodand job satisfaction in adulthood can beexplained, in part, by the relationship betweenCSEs and externally rated job complexity(<strong>Judge</strong>, Bono, & Locke, 2000). This relationshipis at least partially due to the influence ofemotional stability described earlier, but it alsoincorporates the more motivationally loadedtraits of self-esteem, self-efficacy, and locus ofcontrol. This study also further supports the ideathat personality can have a direct effect onobjective job characteristics.To determine if personality characteristicsact as a cause or effect of employee reactions,researchers must find ways to move beyondsimple correlational designs. One way toapproach this problem comes from a two-wavepanel study of bank employees and teachers, inwhich growth needs, strength, NA, and upwardstriving were measured at multiple points intime (Houkes, Janssen, de Jonge, & Bakker,2003). Results showed that Time 1 NA wasassociated with Time 1 emotional exhaustion(βˆ = .44), which in turn led to Time 2 emotionalexhaustion (βˆ = .64); Time 1 NA also led toTime 2 NA (βˆ = .68), which in turn was associatedwith Time 2 emotional exhaustion(βˆ = .32). These results suggest that personalitydispositions may build on themselves over time,with initially minor effects becoming greaterover time as initial tendencies are exacerbated.Among the most thorough longitudinalexaminations of the relationship between personalityand work experiences is the study of asample of 861 individuals tracked from thebeginning of their adult work course at age 18until the age of 26 (Roberts, Caspi, & Moffitt,2003). In this study, a combination of objectivemeasures of occupational attainment, resourcepower, work autonomy, and financial securitywas taken, along with the subjective measuresof satisfaction and involvement. Concentratingonly on those results of moderate effect size(r > .15), negative emotionality was shown to beespecially negatively correlated with occupationalattainment (r =−.27) and financial security(r =−.22). Communal positive emotionality(similar to agreeableness) was correlated withoccupational attainment (r = .19), work satisfaction(r = .15), and work stimulation (r = .15).Agentic positive emotionality (similar to certainaspects of extroversion related to achievementstriving) was positively correlated with occupationalattainment (r = .16) and work stimulation(r = .17). Constraint (similar to the dutifulnesscomponent of conscientiousness) was positivelyrelated to work involvement (r = .18) and financialsecurity (r = .15). These relationshipsgenerally suggest that individual differencesmeasured prior to early work experience do predictobjective job characteristics, although therelationships are relatively modest in size. Thisis especially true in light of the many relationshipsthat were smaller than those reportedhere. This study should be replicated in futureresearch to see how these results generalize toolder populations, given the fact that the adolescentyears are a time of considerable variation inpersonality.A unique aspect of this study was the explicitexamination of how work experiences mightaffect subsequent personality states. To estimatethese effects, personality scores at age 26 wereregressed on personality at age 18 and job features.The residual effects found for job featuresrepresent changes in the respondents’ personality.Again, concentrating on effect sizes overb = .15, the results showed that financial securitywas related to reduced negative emotionality(βˆ = –.19), occupational attainment was associatedwith increased communion (i.e., positivesocial relationships) (βˆ = .16), resource powerwas associated with increased agency (i.e., personalinitiative) (βˆ = .23), work involvement wasassociated with increased agency (βˆ = .20), andwork stimulation was associated with increasedagency (βˆ = .18). No significant relationshipswere found for increasing constraint; work satisfactionand work autonomy were not predictiveof any changes in personality.In sum, the research on personality and jobcharacteristics suggests that there is a complexrelationship that involves personality shapingselection into certain jobs and certain jobsleading to changes in personality. The evidencegenerally suggests that neuroticism is likely toresult in lower levels of actual and perceivedjob characteristics, which can explain at least

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 7272–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUALpart of the relationship between neuroticism and(lower) career success.MODERATORS OF THE<strong>PERSONALITY</strong>/<strong>CAREER</strong>-<strong>SUCCESS</strong>RELATIONSHIPThe previous section proposed a theoreticalmodel showing main effects for personality on avariety of mediating mechanisms that might berelated to career success. However, there aremany contingencies that might alter the relationshipbetween personality and career outcomes.In this section, we consider severalpotential moderators of the career-success/personality relationship.One of the most comprehensive efforts tocreate a theory for incorporating moderators ofthe relationship between personality and workbehavior is associated with the concept oftrait activation (Tett & Burnett, 2003; Tett &Guterman, 2000). According to the trait activationconcept, different situations provide differentopportunities for traits to express themselves.For example, a work environment rich in socialinteractions will be likely to result in biggerdifferences in behavior between introverts andextroverts. Similarly, a work environment withminimal supervision is likely to result in greaterdifferences in behavior between those high inconscientiousness (who will behave in an organized,goal-directed fashion even without supervision)and those low in conscientiousness (whowill take the lack of supervision as an opportunityto relax and reduce work effort). Researchersinterested in studying interactions betweenpersons and situations should look most closely atareas where situations open unique opportunitiesfor personality traits to express themselves. Thestatistical model for trait activation is an interactionbetween individual dispositions and the relationshipbetween personality and an outcome.Situations as Moderators ofPersonality/Career-SuccessRelationshipsOne of the historically strongest theoreticalexplanations for the relationship betweenpersonality and situations is that in weak situations,personality will exert stronger influenceson behavior and attitudes. In other words, whenthere are clear demands on behavior presentedby the situation, it is unlikely that personalitywill matter much. However, when situationsdon’t clearly suggest the correct way to behave,personality tends to have a much stronger effecton how people act.The personality trait of conscientiousnesshas been described as involving both anincreased personal drive for success as well asgreater regulation of one’s behavior to meetstandards. Both these factors are likely to beespecially important in situations where theenvironment provides minimal direct contingenciesfor behavior and minimal regulation ofbehavior. Consistent with this theoretical model,Barrick and Mount (1993) found that the correlationbetween job performance and conscientiousnesswas considerably greater in jobs highin autonomy relative to jobs low in autonomy.One study found that extroversion and agreeablenesswere positively related to contextualperformance only when job autonomy was high(Gellatly & Irving, 2001). Similarly, Type Abehavior exerted strong effects on performance,job satisfaction, and somatic complaints whenperceived control was higher.As noted earlier, Tett and Burnett (2003) proposedthat personality is likely to be most predictiveof behavior when there is a correspondencebetween the trait of interest and situationsthat might elicit the behavior. A clear example isthe relationship between personality traits andsocially loaded situations. A meta-analysis of 11studies found that emotional stability and agreeablenesswere more strongly related to job performancewhen individuals had to engage inteamwork as opposed to jobs that required onlybrief one-on-one interactions with customers(Mount, Barrick, & Stewart, 1998). Evidence suggeststhat despite the low general correlationfound between extroversion and job performance,in a meta-analysis limited to sales jobs,higher levels of achievement striving or “potency”emerged as a significant predictor of supervisorratings of performance (r = .28) and objectivemeasures of sales (r = .26) (Vinchur et al., 1998).A study of a diverse set of 496 individualsfound a significant negative relationship between

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 73Personality and Career Success–•–73agreeableness and salary among people workingin jobs that had a strong people-oriented component,while for those in jobs with a weakerpeople-oriented component there was no relationshipbetween agreeableness and salary(Seibert & Kraimer, 2001).Personality as a Moderator ofSituation/Career-Success RelationshipsAn alternative way to think about the interactionbetween personality and situations is toconsider how personality traits may change therelationship between situations and outcomes.In this case, it is possible that some personalitytraits make it easier for people to take advantageof situations. For example, it is easy to imaginecases in which an opportunity for training ordevelopment would lead to career success ingeneral but would be especially useful for individualswho were higher in proactivity, CSEs, oropenness to experience.This area remains relatively speculativebecause there is not a great deal of researchavailable that examines these possibilities. Onestudy found that requirements for emotional displaysat work were more strongly related to poorphysical health among those who were low inemotional adaptability (Schaubroeck & Jones,2000). There is also evidence that openness toexperience moderates the relationship betweenjob characteristics and job satisfaction in a mannervery similar to the moderating of the relationshipbetween growth needs, strength, andjob characteristics (de Jong, van der Velde, &Jansen, 2001). A large-scale longitudinal study,described earlier, showed that negative affectivitymoderated the relationship between workload,measured at the same time as NA, andemotional exhaustion, measured 1 year later(Houkes et al., 2003). Further research is clearlyneeded in this area.Personality as a Moderator ofPersonality/Career-SuccessRelationshipsBesides situational moderators of the relationshipbetween personality and work behavior,it is also possible that the constellation ofpersonality traits held by individuals mightmoderate one another. In other words, it ispossible that personality traits operate differentlyin combination than they do singly.This is another area where there is not a greatdeal of research. One study found that for jobshigh in interpersonal interactions, the relationshipbetween conscientiousness and job performanceratings was higher for individuals who werehighly agreeable (Witt, Burke, & Barrick, 2002).These results suggest that simply being organized,motivated, and dutiful may not be enoughto create positive social outcomes; individualsmust be sufficiently socially sensitive to makethese positive conscientious traits really becomeevident. Other areas for future research might beto investigate how conscientiousness interactswith openness (open individuals are able to learnmore and innovate but only successfully applythis knowledge to the workplace if they have thediscipline to see their ideas through) or withemotional stability (emotionally unstable individualswho are not conscientious may be prone toperseverating over their worries and never completingtasks, whereas emotionally unstable individualswho are conscientious will work hard tominimize the reason for their worries).Another area in which personality mightbe differentially relevant is the area of creativity.A study conducted by Oldham and Cummings(1996) identified several characteristics, such asinsight, curiosity, and originality, that are associatedwith creativity; it is clear that this study isconceptually close to a measure of openness toexperience. These individual differences in dispositionalpersonality were significantly relatedto obtaining new patents (R 2 = .07) but were notsignificantly related to supervisor ratings ofcreativity (R 2 = .01). However, the interactionbetween motivating potential score and creativepersonality was not significant for obtainingnew patents (R 2 = .00) but was significant forsupervisor ratings of creativity (R 2 = .07). Thissuggests that the interactions between personalityvariables and working conditions may beextremely complex.CONCLUSIONSThe literature on personality and career successhas received increased attention over the years.

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 7474–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUALIt may be a surprise to many readers that theeffect sizes are relatively modest and the resultsrelatively inconsistent. This does not mean, ofcourse, that the effect sizes are zero. Indeed,four of the Big Five traits appear to bear somerelation to either extrinsic or intrinsic careersuccess, with conscientiousness and extraversionbeing associated with slightly higher levelsof extrinsic and intrinsic career success andneuroticism and agreeableness being associatedwith slightly lower levels of career success.Beyond providing an appraisal of the effectsof personality and career success, we sought toreview evidence on why personality is related tocareer success. We reviewed evidence on variousmediators of the relationship between personalityand career success (personality leadsindividuals to possess certain jobs, personalityalso influences individual performance on thejob, personality influences the ways in whichindividuals engage in social interactions atwork). We also discussed the linkage betweenpersonality and job features, as well as dispositionaland situational factors that moderate thepersonality/career-success relationship.Although research on personality and careersuccess has come a long way in the past 20years, there is considerable room for furtherdevelopment. Below, we outline a few areas thatespecially require further study.Need for Careful Research DesignResearchers have tended to rely frequentlyon the use of data gathered at a single point intime to measure the influence of personality oncareer success. While such designs have showna considerable correlation between personalitytraits and career outcomes, several of the studieswe reviewed here suggest that conclusionsfrom such studies could be potentially spurious.Moreover, the debate regarding negative affectivityand career outcomes clearly suggests thatresearchers can be most informative when theymake an effort to eliminate alternative explanationsfor observed correlations.Inclusion of Work-FamilyBalance as an OutcomeBecause men and women are increasinglyoccupying the dual roles of breadwinner andhomemaker, the issue of work-family conflicthas become more prominent (see Greenhausand Foley, Chapter 8). The issue of work-familybalance is conspicuously absent from theliterature on personality and career success,however. Do certain personalities emphasizework over family, or the converse? Are somepersonalities able to better balance work andfamily demands than others? Is the fit betweenwork and family contingent on personality?Does the balance between work and familydemands evolve over time based on personality?ModeratorsAlthough we reviewed various moderatorsof the personality/career-success relationship,other moderators need to be investigated. Someareas for future analysis include family status(e.g., spousal concerns, children, or the need tocare for other family members), labor marketvariables (e.g., unemployment rates), and industrycharacteristics. In the personality/jobperformanceliterature, more systematic progresshas been made on the moderator front, includinginvestigations of the situational (Barrick et al.,1993) and dispositional moderators. Some ofthese moderators should be investigated in thecontext of career success, and others are undoubtedlyworthy of consideration as well.Other TraitsAlthough traits beyond the FFM have beeninvestigated (e.g., proactive personality, agentic/communal orientation), we have only scratchedthe surface of traits that might prove useful.Examination of the lower-order facets of theFFM might prove especially fruitful.In sum, although considerable advances havebeen made in our understanding of the dispositionalbasis of career success, further developmentis needed. In particular, there is a needto investigate factors that explain the relativelymodest and apparently inconsistent results.Process models that investigate mediation willcontribute to our understanding of the specificmechanisms by which personality leads tocareer success; examples of mediators in thecurrent literature include task motivation, socialinteractions, and goal setting. Studies shouldalso make a greater effort to investigate some of

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 75Personality and Career Success–•–75the ways in which personality interacts with theenvironment to produce career success bystudying the ways in which traits moderate theeffect of situations and situations moderate theeffects of traits.NOTE1. Here and throughout the chapter, the followingstatistical notation will be used: ρˆ = estimatedcorrelation corrected for measurement error,rˆu = estimated uncorrected correlation, βˆ = estimatedstandardized regression coefficient, and rˆ = estimatedzero-order correlation (uncorrected).REFERENCESAbele, A. E. (2003). The dynamics of masculineagenticand feminine-communal traits: Findingsfrom a prospective study. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 85, 768–776.Aryee, S., Lo, S., & Kang, I. (1999). Antecedents ofearly career stage mentoring among Chineseemployees. Journal of Organizational Behavior,20, 563–576.Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Fivepersonality dimensions and job performance: Ameta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1–26.Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1993). Autonomy asa moderator of the relationships between the BigFive personality dimensions and job performance.Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 111–118.Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Gupta, R. (2003).Meta-analysis of the relationship between the fivefactormodel of personality and Holland’s occupationaltypes. Personnel Psychology, 56, 45–74.Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Strauss, J. P. (1993).Conscientiousness and performance of sales representatives:Test of the mediating effects of goal setting.Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 715–722.Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., & Piotrowski, M.(2002). Personality and job performance: Test ofthe mediating effects of motivation among salesrepresentatives. Journal of Applied Psychology,87, 43–51.Blaikie, N. W. (1977). The meaning and measurementof occupational prestige. Australian andNew Zealand Journal of Sociology, 13, 102–115.Bono, J. E., & <strong>Judge</strong>, T. A. (2003). Core selfevaluations:A review of the trait and its role injob satisfaction and job performance. EuropeanJournal of Personality, 17, S5–S18.Borman, W. C., Penner, L. A., Allen, T. D., &Motowidlo, S. J. (2001). Personality predictors ofcitizenship performance. International Journal ofSelection & Assessment, 9, 52–69.Borman, W. C., White, L. A., Pulakos, E. D., & Oppler,S. H. (1991). Models of supervisory job performanceratings. Journal of Applied Psychology,76, 863–872.Boudreau, J. W., Boswell, W. R., & <strong>Judge</strong>, T. A.(2001). Effects of personality on executivecareer success in the United States and Europe.Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 53–81.Bozionelos, N. (2004). Mentoring provided: Relationto mentor’s career success, personality, andmentoring received. Journal of VocationalBehavior, 64, 24–46.Brief, A. P., Burke, M. J., George, J. M., Robinson, B.S., & Webster, J. (1988). Should negative affectivityremain an unmeasured variable in thestudy of job stress? Journal of AppliedPsychology, 73, 193–198.Burke, M. J., Brief, A. P., & George, J. M. (1993). Therole of negative affectivity in understanding relationsbetween self-reports of stressors and strains:A comment on the applied psychology literature.Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 402–412.Caspi, A., Elder, G. H., Jr., & Bem, D. J. (1988).Moving away from the world: Life course patternsof shy children. Developmental Psychology,24, 824–831.Chan, D., & Schmitt, N. (2000). Interindividual differencesin intraindividual changes in proactivityduring organizational entry: A latent growthmodeling approach to understanding newcomeradaptation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85,190–210.Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1988). Personalityin adulthood: A six-year longitudinal study ofself-reports and spouse ratings on the NEOPersonality Inventory. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 54, 853–863.Crant, J. M. (1995). The proactive personality scaleand objective job performance among real estateagents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 532–537.De Fruyt, F., & Mervielde, I. (1999). RIASEC typesand Big Five traits as predictors of employmentstatus and nature of employment. PersonnelPsychology, 52, 701–727.de Jong, R. D., van der Velde, M. E. G., & Jansen,P. G. W. (2001). Openness to experience and

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 7676–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUALgrowth need strength as moderators betweenjob characteristics and satisfaction. InternationalJournal of Selection & Assessment, 9,350–356.DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happypersonality: A meta-analysis of 137 personalitytraits and subjective well-being. PsychologicalBulletin, 124, 197–229.Diefendorff, J. M., & Richard, E. M. (2003).Antecedents and consequences of emotional displayrule perceptions. Journal of AppliedPsychology, 88, 284–294.Digman, J. M. (1989). Five robust trait dimensions:Development, stability, and utility. Journal ofPersonality, 57, 195–214.Dunn, W. S., Mount, M. K., Barrick, M. R., & Ones,D. S. (1995). Relative importance of personalityand general mental ability in managers’ judgmentsof applicant qualifications. Journal ofApplied Psychology, 80, 500–509.Eliot, T. S. (1939). The family reunion. New York:Harcourt, Brace.Erez, A., & <strong>Judge</strong>, T. A. (2001). Relationship of coreself-evaluations to goal setting, motivation, andperformance. Journal of Applied Psychology,86, 1270–1279.Fagenson-Eland, E. A., & Baugh, S. G. (2001).Personality predictors of protege mentoringhistory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,31, 2502–2517.Featherman, D. L., Jones, F. L., & Hauser, R. M.(1975). Assumptions of social mobility researchin the U.S.: The case of occupational status.Social Science Research, 4, 329–360.Friedman, H. S., Tucker, J. S., Schwartz, J. E., Martin,L. R., Tomlinson-Keasey, C., Wingard, D. L.,et al. (1995). Childhood conscientiousness andlongevity: Health behaviors and cause of death.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68,696–703.Ganzeboom, H. B. G., & Treiman, D. J. (1996).Internationally comparable measures of occupationalstatus for the 1988 International StandardClassification of Occupations. Social ScienceResearch, 25, 201–239.Gattiker, U. E., & Larwood, L. (1988). Predictors formanagers’ career mobility, success, and satisfaction.Human Relations, 41, 569–591.Gellatly, I. R., & Irving, P. G. (2001). Personality,autonomy, and contextual performance of managers.Human Performance, 14, 231–245.Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description ofpersonality”: The Big-Five factor structure.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,59, 1216–1229.Guion, R. M., & Gottier, R. F. (1965). Validity ofpersonality measures in personnel selection.Personnel Psychology, 18, 135–164.Harrell, T. W., & Alpert, B. (1989). Attributes of successfulMBAs: A 20-year longitudinal study.Human Performance, 2, 301–322.Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: Atheory of vocational personalities and work environments(3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: PsychologicalAssessment Resources.Houkes, I., Janssen, P. P. M., de Jonge, J., &Bakker, A. B. (2003). Personality, job featuresand employee well-being: A longitudinalanalysis of additive and moderating effects.Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8,20–38.Howard, A., & Bray, D. W. (1994). Predictions ofmanagerial success over time: Lessons from theManagement Progress Study. In K. E. Clark &M. B. Clark (Eds.), Measures of leadership(pp. 113–130). West Orange, NJ: LeadershipLibrary of America.Huffcutt, A. I., Weekley, J. A., Wiesner, W. H.,Degroot, T. G., & Jones, C. (2001). Comparisonof situational and behavior description interviewquestions for higher-level positions. PersonnelPsychology, 54, 619–644.Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (1990). Methodsof meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias inresearch findings. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Hurtz, G. M., & Donovan, J. J. (2000). Personalityand job performance: The Big Five revisited.Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 869–879.Jaskolka, G., Beyer, J. M., & Trice, H. M. (1985).Measuring and predicting managerial success.Journal of Vocational Behavior, 26, 189–205.<strong>Judge</strong>, T. A., Bono, J. E., & Locke, E. A. (2000).Personality and job satisfaction: The mediatingrole of job characteristics. Journal of AppliedPsychology, 85, 237–249.<strong>Judge</strong>, T. A., & Bretz, R. D. (1994). Political influencebehavior and career success. Journal ofManagement, 20, 43–65.<strong>Judge</strong>, T. A., Cable, D. M., Boudreau, J. W., & Bretz,R. D. (1995). An empirical investigation of thepredictors of executive career success. PersonnelPsychology, 48, 485–519.

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 77Personality and Career Success–•–77<strong>Judge</strong>, T. A., Erez, A., & Bono, J. E. (2003). The coreself-evaluations scale: Development of a measure.Personnel Psychology, 56, 303–331.<strong>Judge</strong>, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002).Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction:A meta-analysis. Journal of AppliedPsychology, 87, 530–541.<strong>Judge</strong>, T. A., Higgins, C., Thoresen, C. J., & Barrick,M. R. (1999). The Big Five personality traits,general mental ability, and career success acrossthe life span. Personnel Psychology, 52, 621–652.<strong>Judge</strong>, T. A., Locke, E. A., & Durham, C. C. (1997).The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: Acore evaluations approach. Research in OrganizationalBehavior, 19, 151–188.Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Wanberg, C. R. (2003).Unwrapping the organizational entry process:Disentangling multiple antecedents and theirpathways to adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology,88, 779–794.Korman, A. K., Mahler, S. R., & Omran, K. A. (1983).Work ethics and satisfaction, alienation, and otherreactions. In W. B. Walsh & S. H. Osipow (Eds.),Handbook of vocational psychology (Vol. 2,pp. 181–206). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Kristof-Brown, A., Barrick, M. R., & Franke, M.(2002). Applicant impression management:Dispositional influences and consequences forrecruiter perceptions of fit and similarity.Journal of Management, 28, 27–46.Levin, I., & Stokes, J. P. (1989). Dispositional approachto job satisfaction: Role of negative affectivity.Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 752–758.Lubinski, D., Benbow, C. P., & Ryan, J. (1995).Stability of vocational interests among the intellectuallygifted from adolescence to adulthood:A 15-year longitudinal study. Journal of AppliedPsychology, 80, 196–200.McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1991). AddingLiebe und Arbeit: The full five-factor model andwell-being. Personality and Social PsychologyBulletin, 17, 227–232.McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Personalitytrait structure as a human universal. AmericanPsychologist, 52, 509–516.McCrae, R. R., & John, O. P. (1992). An introductionto the five-factor model and its applications.Journal of Personality, 2, 175–215.Melamed, T. (1996a). Career success: An assessment ofa gender-specific model. Journal of Occupationaland Organizational Psychology, 69, 217–242.Melamed, T. (1996b). Validation of a stage model ofcareer success. Applied Psychology: An InternationalReview, 45, 35–65.Mount, M. K., Barrick, M. R., & Stewart, G. L.(1998). Five-factor model of personality andperformance in jobs involving interpersonalinteractions. Human Performance, 11, 145–165.Norman, W. T. (1963). Toward an adequate taxonomy ofpersonality attributes: Replicated factor structure inpeer nomination personality ratings. Journal ofAbnormal and Social Psychology, 66, 574–583.Oldham, G. R., & Cummings, A. (1996). Employeecreativity: Personal and contextual factors atwork. Academy of Management Journal, 39,607–634.Orpen, C. (1983). The development and validation ofan adjective check-list measure of managerialneed for achievement. Psychology, 20, 38–42.Pincus, A. L., Gurtman, M. B., & Ruiz, M. A. (1998).Structural analysis of social behavior (SASB):Circumplex analyses and structural relationswith the interpersonal circle and the five-factormodel of personality. Journal of Personality andSocial Psychology, 74, 1629–1645.Poole, M. E., Langan-Fox, J., & Omodei, M. (1993).Contrasting subjective and objective criteria asdeterminants of perceived career success: Alongitudinal study. Journal of Occupational andOrganizational Psychology, 66, 39–54.Rawls, D. J., & Rawls, J. R. (1968). Personality characteristicsand personal history data of successfuland less successful executives. PsychologicalReports, 23, 1032–1034.Roberts, B. W., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2003).Work experiences and personality developmentin young adulthood. Journal of Personality &Social Psychology, 84, 582–593.Rynes, S., & Gerhart, B. (1990). Interviewer assessmentsof applicant “fit”: An exploratory investigation.Personnel Psychology, 43, 15–35.Salgado, J. F. (1997). The five factor model of personalityand job performance in the EuropeanCommunity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82,30–43.Salgado, J. F. (2002). The Big Five personality dimensionsand counterproductive behaviors. InternationalJournal of Selection & Assessment, 10,117–125.Schaubroeck, J., & Jones, J. R. (2000). Antecedentsof workplace emotional labor dimensionsand moderators of their effects on physical

04-Gunz.qxd 4/7/2007 5:39 PM Page 7878–•–MAIN CURRENTS IN THE STUDY OF <strong>CAREER</strong>: <strong>CAREER</strong>S <strong>AND</strong> THE INDIVIDUALsymptoms. Journal of Organizational Behavior,21, 163–183.Schmitt, N. (2004). Beyond the Big Five: Increases inunderstanding and practical utility. HumanPerformance, 17, 347–357.Schooler, C., & Schoenbach, C. (1994). Social class,occupational status, occupational self-direction,and job income: A cross-national examination.Sociological Forum, 9, 431–458.Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (1999).Proactive personality and career success. Journalof Applied Psychology, 84, 416–427.Seibert, S. E., & Kraimer, M. L. (2001). The fivefactormodel of personality and career success.Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 1–21.Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Crant, J. M. (2001).What do proactive people do? A longitudinalmodel linking proactive personality and careersuccess. Personnel Psychology, 54, 845–874.Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Liden, R. C. (2001).A social capital theory of career success.Academy of Management Journal, 44, 219–248.Spector, P. E., Jex, S. M., & Chen, P. Y. (1995).Relations of incumbent affect-related personalitytraits with incumbent and objective measures ofcharacteristics of jobs. Journal of OrganizationalBehavior, 16, 59–65.Tett, R. P., & Burnett, D. D. (2003). A personality traitbasedinteractionist model of job performance.Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 500–517.Tett, R. P., & Guterman, H. A. (2000). Situation traitrelevance, trait expression, and cross-situationalconsistency: Testing a principle of trait activation.Journal of Research in Personality, 34, 397–423.Tharenou, P. (1997). Managerial career advancement.International Review of Industrial and OrganizationalPsychology, 12, 39–93.Tupes, E. C., & Christal, R. E. (1961). Recurrent personalityfactors based on trait ratings (TechnicalReport No. 61–97). Wright Patterson AFB, OH:USAF Aeronautical Systems Division.Turban, D. B., & Dougherty, T. W. (1994). Role of protegepersonality in receipt of mentoring andcareer success. Academy of Management Journal,37, 688–702.Vinchur, A. J., Schippmann, J. S., Switzer, F. S., &Roth, P. L. (1998). A meta-analytic review ofpredictors of job performance for salespeople.Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 586–597.Viswesvaran, C., Ones, D. S., & Hough, L. M.(2001). Do impression management scales inpersonality inventories predict managerial jobperformance ratings? International Journal ofSelection & Assessment, 9, 277–289.Wallace, J. E. (2001). The benefits of mentoring forfemale lawyers. Journal of Vocational Behavior,58, 366–391.Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000).Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in thesocialization process. Journal of AppliedPsychology, 85, 373–385.Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1997). Extraversionand its positive emotional core. In R. Hogan,J. Johnson, & S. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook ofpersonality psychology (pp. 767–793). SanDiego, CA: Academic Press.Watson, D., Pennebaker, J. W., & Folger, R. (1986).Beyond negative affectivity: Measuring stress andsatisfaction in the work place. Journal of OrganizationalBehavior Management, 8, 141–157.Witt, L. A., Burke, L. A., & Barrick, M. A. (2002).The interactive effects of conscientiousness andagreeableness on job performance. Journal ofApplied Psychology, 87, 164–169.