Amicus Curiae Brief to U.S. Supreme Court in Fisher v. University of ...

Amicus Curiae Brief to U.S. Supreme Court in Fisher v. University of ...

Amicus Curiae Brief to U.S. Supreme Court in Fisher v. University of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

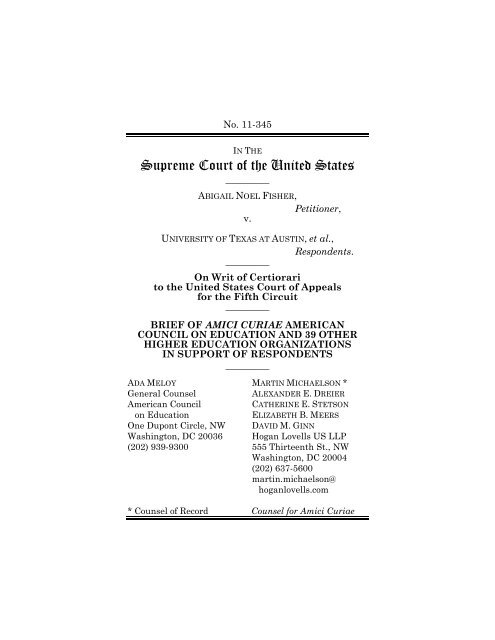

No. 11-345IN THE<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> the United States_________ABIGAIL NOEL FISHER,Petitioner,v.UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, et al.,Respondents._________On Writ <strong>of</strong> Certiorari<strong>to</strong> the United States <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> Appealsfor the Fifth Circuit_________BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE AMERICANCOUNCIL ON EDUCATION AND 39 OTHERHIGHER EDUCATION ORGANIZATIONSIN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS_________ADA MELOYGeneral CounselAmerican Councilon EducationOne Dupont Circle, NWWash<strong>in</strong>g<strong>to</strong>n, DC 20036(202) 939-9300MARTIN MICHAELSON *ALEXANDER E. DREIERCATHERINE E. STETSONELIZABETH B. MEERSDAVID M. GINNHogan Lovells US LLP555 Thirteenth St., NWWash<strong>in</strong>g<strong>to</strong>n, DC 20004(202) 637-5600mart<strong>in</strong>.michaelson@hoganlovells.com* Counsel <strong>of</strong> Record Counsel for Amici <strong>Curiae</strong>

AMICI ON THIS BRIEFAmerican Council on EducationAmerican Anthropological AssociationAmerican Association <strong>of</strong> Colleges <strong>of</strong> PharmacyAmerican Association <strong>of</strong> Community CollegesAmerican Association <strong>of</strong> State Colleges and UniversitiesAmerican Association <strong>of</strong> <strong>University</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essorsAmerican College Personnel AssociationAmerican Indian Higher Education ConsortiumAmerican Speech-Language-Hear<strong>in</strong>g AssociationAssociation <strong>of</strong> American Colleges and UniversitiesAssociation <strong>of</strong> American UniversitiesAssociation <strong>of</strong> Catholic Colleges and UniversitiesAssociation <strong>of</strong> Community College TrusteesAssociation <strong>of</strong> Govern<strong>in</strong>g Boards <strong>of</strong> Universities and CollegesAssociation <strong>of</strong> Jesuit Colleges and UniversitiesAssociation <strong>of</strong> Public and Land Grant UniversitiesAssociation <strong>of</strong> Research LibrariesAssociation <strong>to</strong> Advance Collegiate Schools <strong>of</strong> Bus<strong>in</strong>essCollege and <strong>University</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Association for HumanResourcesThe Common ApplicationCouncil for Advancement and Support <strong>of</strong> EducationCouncil for Christian Colleges and UniversitiesCouncil for Higher Education AccreditationCouncil for Opportunity <strong>in</strong> EducationCouncil <strong>of</strong> Graduate SchoolsCouncil <strong>of</strong> Independent CollegesCouncil on Social Work EducationEDUCAUSEGraduate Management Admissions CouncilGroup for the Advancement <strong>of</strong> Doc<strong>to</strong>ral Education <strong>in</strong> Social WorkNational Action Council for M<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>in</strong> Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g, Inc.National Association for Equal Opportunity <strong>in</strong> Higher EducationNational Association <strong>of</strong> College and <strong>University</strong> Bus<strong>in</strong>ess OfficersNational Association <strong>of</strong> Diversity Officers <strong>in</strong> Higher EducationNational Association <strong>of</strong> Independent Colleges and UniversitiesNational Association <strong>of</strong> Student F<strong>in</strong>ancial Aid Adm<strong>in</strong>istra<strong>to</strong>rsNational Collegiate Athletic AssociationSouthern Association <strong>of</strong> Colleges and Schools Commission onCollegesStudent Affairs Adm<strong>in</strong>istra<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> Higher EducationThurgood Marshall College Fund

TABLE OF CONTENTSPageTABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iiiSTATEMENT OF INTEREST .................................... 1SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 2ARGUMENT ............................................................... 3I. THE INTEREST IN STUDENTDIVERSITY IS EVEN MORECOMPELLING NOW THAN IT WAS ADECADE AGO ................................................... 3A. Student Diversity Is A Compell<strong>in</strong>gInterest .......................................................... 4B. Student Diversity Is AcutelyNeeded Today ............................................... 81. Students Must Be Equipped ToNavigate An InterconnectedWorld ....................................................... 82. The Educational BenefitsDiversity Confers Rema<strong>in</strong>Essential To Higher Education ............ 11II. HIGHER EDUCATIONINSTITUTIONS NEEDFLEXIBILITY TO DEFINE ANDATTAIN DIVERSITY ...................................... 17A. American Higher EducationThrives On Pluralism ................................. 18(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Cont<strong>in</strong>ued1. American Higher Education IsCharacterized By The Variety OfInstitutional Missions ........................... 182. The Government HasRepeatedly Endorsed The ValueOf A Decentralized HigherEducation System In WhichInstitutions Pursue TheirRespective Missions In TheirRespective Ways .................................... 20B. Each Institution Must Def<strong>in</strong>eDiversity In A Manner ConsistentWith Its Mission ......................................... 28C. Properly Conducted Holistic,Individualized Review Tailored ToInstitutional Mission Is A LawfulAnd Effective Means To Atta<strong>in</strong>Diversity...................................................... 31CONCLUSION .......................................................... 33ADDENDUM: AMICI ON THIS BRIEF .................. 1a(ii)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIESPage(s)CASES:Board <strong>of</strong> Cura<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> Univ. <strong>of</strong> Mo. v.Horowitz, 435 U.S. 78 (1978) ............... 7, 22, 24Board <strong>of</strong> Educ., Island Trees Union FreeSch. Dist. No. 26 v. Pico,457 U.S. 853 (1982)......................................... 14Christian Legal Soc’y v. Mart<strong>in</strong>ez,130 S. Ct. 2971 (2010) .................................... 30DeRolph v. State,677 N.E.2d 733 (Ohio 1997) ........................... 14Edwards v. California Univ. <strong>of</strong> Penn.,156 F.3d 488 (3d Cir. 1998) .............................. 7Ew<strong>in</strong>g v. Bd. <strong>of</strong> Regents <strong>of</strong>Univ. <strong>of</strong> Mich.,742 F.2d 913 (6th Cir. 1984) .......................... 23<strong>Fisher</strong> v. Univ. <strong>of</strong> Tex.,631 F.3d 213 (5th Cir. 2011) .......................... 32<strong>Fisher</strong> v. Univ. <strong>of</strong> Tex.,644 F.3d 307 (5th Cir. 2011) .......................... 29Grutter v. Boll<strong>in</strong>ger,539 U.S. 306 (2003)................................. passimHamil<strong>to</strong>n v. Regents <strong>of</strong> Univ. <strong>of</strong> Cal.,293 U.S. 245 (1934)................................... 22, 25Johnson v. California,543 U.S. 499 (2005)......................................... 31(iii)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>uedKeyishian v. Board <strong>of</strong> Regents <strong>of</strong>Univ. <strong>of</strong> N.Y.,385 U.S. 589 (1967)......................................... 28M’Culloch v. Maryland,17 U.S. 216 (1819) .......................................... 21Mueller v. Allen,463 U.S. 388 (1983)......................................... 14Parents Involved <strong>in</strong> Community Schools v.Seattle School Dist. No. 1,551 U.S. 701 (2007)................................... 30, 33Plyler v. Doe,457 U.S. 202 (1982)......................................... 15Regents <strong>of</strong> Univ. <strong>of</strong> Cal. v. Bakke,438 U.S. 265 (1978)............................. 4, 5, 7, 23Regents <strong>of</strong> Univ. <strong>of</strong> Mich. v. Ew<strong>in</strong>g,474 U.S. 214 (1985)................................. passimSweezy v. New Hampshire,354 U.S. 234 (1957)............................. 22, 23, 28Taylor v. Columbian Univ.,226 U.S. 126 (1912)................................... 21, 22Trustees <strong>of</strong> Dartmouth College v.Woodward,17 U.S. 518 (1819) .............................. 20, 21, 25United States v. Lopez,514 U.S. 549 (1995)......................................... 19(iv)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>ued<strong>University</strong> v. People,99 U.S. 309 (1878) .......................................... 21Wash<strong>in</strong>g<strong>to</strong>n Univ. v. Rouse,75 U.S. 439 (1869) .......................................... 21STATUTES:20 U.S.C. §§ 1001-1002 ........................................ 2720 U.S.C. § 1232a ................................................. 28Morrill Land-Grant Act, 12 Stat. 503 (1862) ...... 25Pub. L. No. 89-329, 79 Stat. 1219 ........................ 26Pub. L. No. 92-318, 86 Stat. 235 .......................... 27Pub. L. No. 95-561, 92 Stat. 2143 ........................ 27Pub. L. No. 98-511, 98 Stat. 2366 ........................ 27Pub. L. No. 99-498, 100 Stat. 1268 ...................... 27Pub. L. No. 102-325, 106 Stat. 448 ...................... 27Pub. L. No. 105-244, 112 Stat. 1581 .................... 27Pub. L. No. 110-315, 122 Stat. 3078 .................... 27LEGISLATIVE:H.R. Rep. No. 78-1418 (1944) .............................. 26OTHER AUTHORITIES:1 James Kent, Commentaries on AmericanLaw 416-417 (O.W. Holmes ed.,12th ed. 1873) ................................................. 21(v)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>ued1 Richard H<strong>of</strong>stadter and Wilson Smitheds., American Higher Education:A Documentary His<strong>to</strong>ry 157 (1961) ................ 24A.L. An<strong>to</strong>nio et al., Approach<strong>in</strong>g DiversityWork <strong>in</strong> the <strong>University</strong>: Lessons from anAmerican Context .............................................. 5Alexander Meikeljohn, Education BetweenTwo Worlds (1942) .......................................... 15American Council on Educ., U.S. BranchCampuses Abroad (Sept. 2009) ........................ 9Arthur H. Comp<strong>to</strong>n, Foreword <strong>to</strong>Hus<strong>to</strong>n Smith, The Purposes <strong>of</strong> HigherEducation (1955) ............................................. 10As the World Turns: Implications <strong>of</strong> GlobalShifts <strong>in</strong> Higher Education for Theory,Research and Practice(Walter R. Allen et al. eds. 2012) ..................... 5Axel Dreher, KOF Swiss EconomicInstitute, KOF Index <strong>of</strong> Globalization(Mar. 16, 2012) .................................................. 8Benjam<strong>in</strong> Frankl<strong>in</strong>, Proposals Relat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong>the Education <strong>of</strong> Youth <strong>in</strong> Pennsylvania(1749, repr<strong>in</strong>t 1931) ........................................ 16Carl F. Kaestle, Pillars <strong>of</strong> the Republic:Common Schools and American Society1780-1860 (Eric Foner ed. 1983) .................... 16(vi)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>uedCarl Swisher, American ConstitutionalDevelopment (1943) ......................................... 25Carnegie Comm’n on Higher Educ., Reformon Campus: Chang<strong>in</strong>g Students,Chang<strong>in</strong>g Academic Programs (1972) ........... 31Chester E. F<strong>in</strong>n, Jr., Scholars, Dollars andBureaucrats (1978) ......................................... 27Civic Learn<strong>in</strong>g and DemocraticEngagement, A Crucible Moment:College Learn<strong>in</strong>g and Democracy’sFuture (2012) .................................................. 14David J. Barron, The Promise <strong>of</strong> Cooley’sCity: Traces <strong>of</strong> Local Constitutionalism,147 U. Pa. L. Rev. 487 (1999) ......................... 14Derek Bok, Higher Learn<strong>in</strong>g (1986) .................... 20Diane N. Ruble, A Phase Model <strong>of</strong>Transitions: Cognitive and MotivationalConsequences, 26 Advances <strong>in</strong>Experimental Social Psych. 163 (1994) ......... 12Earle D. Ross, Democracy’s College: TheLand-Grant Movement <strong>in</strong> the FormativeStage (1942) .................................................... 26Edward H. Reisner, Antecedents <strong>to</strong> theFederal Act Concern<strong>in</strong>g Education,11 Educational Record 196 (July 1930) ......... 24(vii)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>uedF.W. Garforth, Educative Democracy: JohnStuart Mill on Education <strong>in</strong> Society(1980) ............................................................... 12Frank Donovan ed., The John AdamsPapers 182 (1965) ........................................... 16Henry Rosovsky, Highest Education,197 The New Republic 13 (1987) ................... 19Hus<strong>to</strong>n Smith, The Purposes <strong>of</strong> HigherEducation (1955) ............................................. 11J.H.C. Newman, The Idea <strong>of</strong> a <strong>University</strong>(M.J. Svaglic ed., Univ. <strong>of</strong> Notre DamePress 1982) (1873) .......................................... 11Jean Piaget, Piaget’s Theory, <strong>in</strong>1 Carmichael’s Manual <strong>of</strong> ChildPsychology (P.H. Mussen ed.,3d ed. Wiley 1970) .......................................... 12John Dewey, Democracy andEducation (Free Press 1966) (1916) ............... 16John S. Brubacher & Willis Rudy, HigherEducation <strong>in</strong> Transition: A His<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong>American Colleges and Universities (4thed. 1997) (1958) ............................................... 20John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, <strong>in</strong> ThreeEssays 134 (Oxford Univ. Press 1975)(1859) ............................................................... 15(viii)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>uedJon Bruner, American Leadership <strong>in</strong>Science, Measured <strong>in</strong> Nobel Prizes(Oct. 5, 2011) ................................................... 18Jonathan R. Cole, The Great American<strong>University</strong> (2009) ............................................ 18Lee C. Boll<strong>in</strong>ger, Why Diversity Matters,Chronicle <strong>of</strong> Higher Education(June 1, 2007) ................................................. 10Mart<strong>in</strong> Trow, Federalism <strong>in</strong> AmericanHigher Education, <strong>in</strong> Higher Learn<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> America 1980-2000 (Arthur Lev<strong>in</strong>eed., 1993) ................................................... 20, 26Menachem Wecker, Where the Fortune 500CEOs Went <strong>to</strong> School, U.S. News &World Report (May 14, 2012) ......................... 18Mitra Toossi, Labor Force Projections <strong>to</strong>2020: A More Slowly Grow<strong>in</strong>gWorkforce, Monthly Labor Review(Jan. 2012) ........................................................ 8Nat’l Task Force on Civic Learn<strong>in</strong>g andDemocratic Engagement, A CrucibleMoment: College Learn<strong>in</strong>g andDemocracy’s Future (2012) ............................. 14N. Bowman, College Diversity Experiencesand Cognitive Development: A Meta-Analysis, 80 Review <strong>of</strong> EducationalResearch (2010) ................................................ 5(ix)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>uedN. Denson & M.J. Chang, Racial DiversityMatters: The Impact <strong>of</strong> Diversity-Related Student Engagement andInstitutional Context,46 American Educational ResearchJournal 322 (2009) ............................................ 5N. Gottfredson et al., Does Diversity atUndergraduate Institutions InfluenceStudent Outcomes?, 1 Journal <strong>of</strong>Diversity <strong>in</strong> Higher Education 80 (2008) ......... 6Noah Webster, On the Education <strong>of</strong> Youth<strong>in</strong> America (1790), <strong>in</strong> Essays onEducation <strong>in</strong> the Early Republic(Frederick Rudolph ed., 1965) ........................ 16Organization for Econ. Cooperation & Dev.,Education at a Glance: OECDIndica<strong>to</strong>rs (2011) ............................................. 18Peter B. Pufall, The Development <strong>of</strong>Thought: On Perceiv<strong>in</strong>g and Know<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>in</strong> Robert Shaw & John Bransford,Perceiv<strong>in</strong>g, Act<strong>in</strong>g, and Know<strong>in</strong>g:Toward an Ecological Psychology (1977) ....... 12Press Release, United States CensusBureau, Most Children Younger ThanAge 1 Are M<strong>in</strong>orities (May 17, 2012) ................ 8Raymond V. Gilmart<strong>in</strong>, Diversity andCompetitive Advantage at Merck,Harv. Bus. Rev. (Jan. – Feb. 1999) ................ 10(x)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>uedRobert M. Hutch<strong>in</strong>s, The Higher Learn<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> America (Transaction Publishers1995) (1936) .................................................... 11Robert Shaw & John Bransford, Perceiv<strong>in</strong>g,Act<strong>in</strong>g, and Know<strong>in</strong>g: Toward anEcological Psychology (1977) .......................... 12Roy J. Honeywell, Educational Works <strong>of</strong>Thomas Jefferson (1931) ................................ 25S. Hurtado & L. D’Angelo, L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gDiversity and Civic-M<strong>in</strong>ded Practiceswith Student Outcomes: New Evidencefrom National Surveys,98 Liberal Education 2 (2012) .......................... 5Sabr<strong>in</strong>a Tavernise, Whites Account forUnder Half <strong>of</strong> Births <strong>in</strong> U.S.,N.Y. Times, May 17, 2012 ................................ 8Scott Jaschik, International Campuses onthe Rise, Inside Higher Ed,Sept. 3, 2009 ..................................................... 9Shanghai Jiao Tong <strong>University</strong>, AcademicRank<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> World Universities: 2011 ............. 18Uri Friedman & Kedar Pavgi, Head <strong>of</strong> theClass?, Foreign Policy (Nov. 18, 2011) ........... 18U.S. Dep’t <strong>of</strong> State & Institute <strong>of</strong> Int’lEduc., Study Abroad by U.S. StudentsRose <strong>in</strong> 2009/10 with More StudentsGo<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> Less Traditional Dest<strong>in</strong>ations(Nov. 14, 2011) .................................................. 9(xi)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Cont<strong>in</strong>uedU.S. Dep’t <strong>of</strong> State, Report <strong>of</strong> the VisaOffice, Classes <strong>of</strong> Nonimmigrants IssuedVisas (2010) ....................................................... 9William G. Bowen & Derek Bok, The Shape<strong>of</strong> the River (1998) ........................................... 10William G. Bowen et al., Equity andExcellence <strong>in</strong> American HigherEducation (2005) ............................................. 18(xii)

IN THE<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> the United States_________No. 11-345_________ABIGAIL NOEL FISHER,Petitioner,v.UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN, et al.,Respondents._________On Writ <strong>of</strong> Certiorari<strong>to</strong> the United States <strong>Court</strong> <strong>of</strong> Appealsfor the Fifth Circuit_________BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE AMERICANCOUNCIL ON EDUCATION AND 39 OTHERHIGHER EDUCATION ORGANIZATIONS INSUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS_________STATEMENT OF INTEREST 1Amici are 40 associations <strong>of</strong> colleges, universities,educa<strong>to</strong>rs, trustees, and other representatives <strong>of</strong>higher education <strong>in</strong> the United States. Amicirepresent public, <strong>in</strong>dependent, large, small, urban,rural, denom<strong>in</strong>ational, non-denom<strong>in</strong>ational,graduate, and undergraduate <strong>in</strong>stitutions andfaculty. American higher education <strong>in</strong>stitutions1 No party or counsel for a party authored or paid for thisbrief <strong>in</strong> whole or <strong>in</strong> part, or made a monetary contribution <strong>to</strong>fund the brief’s preparation or submission. No one other thanamici or their members or counsel made a monetarycontribution <strong>to</strong> the brief. All parties filed blanket amicusconsent letters.

2enroll over 20 million students. For decades amicihave worked <strong>to</strong> achieve student diversity.<strong>Amicus</strong> American Council on Education (ACE)represents all higher education sec<strong>to</strong>rs. Itsapproximately 1800 members <strong>in</strong>clude a substantialmajority <strong>of</strong> United States colleges and universities.Founded <strong>in</strong> 1918, ACE seeks <strong>to</strong> foster high standards<strong>in</strong> higher education, believ<strong>in</strong>g a strong highereducation system <strong>to</strong> be the corners<strong>to</strong>ne <strong>of</strong> ademocratic society. Among its <strong>in</strong>itiatives, ACE had amajor role <strong>in</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>g the Commission onM<strong>in</strong>ority Participation <strong>in</strong> Education and AmericanLife, chaired by former Presidents Ford and Carter,which issued One-Third <strong>of</strong> a Nation (1988), a repor<strong>to</strong>n m<strong>in</strong>ority matriculation, retention, andgraduation. ACE regularly contributes amicus briefson issues <strong>of</strong> importance <strong>to</strong> the education sec<strong>to</strong>r.The Addendum conta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>formation on the otheramici on this brief.SUMMARY OF ARGUMENTA diverse student body is essential <strong>to</strong> theeducational objectives <strong>of</strong> colleges and universities.This <strong>Court</strong> held <strong>in</strong> Grutter v. Boll<strong>in</strong>ger, 539 U.S. 306(2003), that obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the educational benefits thatflow from a diverse student body is a compell<strong>in</strong>ggovernmental <strong>in</strong>terest that justifies narrowlytailored consideration <strong>of</strong> race <strong>in</strong> college admissions.The hold<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Grutter is even more urgent <strong>to</strong>daythan it was <strong>in</strong> 2003. Higher education <strong>in</strong>stitutionsmust equip their students <strong>to</strong> work and live <strong>in</strong> an<strong>in</strong>terconnected world, stimulate students’ <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong>the new and unfamiliar, and prepare them <strong>to</strong>understand and account for differences. Diversity

3thus rema<strong>in</strong>s a compell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> highereducation.Diversity is not a one-size-fits-all concept,however. Each higher education <strong>in</strong>stitution mustdef<strong>in</strong>e student body diversity <strong>in</strong> a manner consistentwith its educational mission. As the <strong>Court</strong>recognized <strong>in</strong> Grutter, when an <strong>in</strong>stitutiondeterm<strong>in</strong>es its educational goals—<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g itsconception <strong>of</strong> diversity—it makes an educationaljudgment that merits deference. <strong>Court</strong>s may rightlyscrut<strong>in</strong>ize the means chosen <strong>to</strong> pursue diversity, butthey defer <strong>to</strong> educa<strong>to</strong>rs’ experience and expertise <strong>in</strong>determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g what sort <strong>of</strong> diversity, and how much,their <strong>in</strong>stitution needs.Petitioner would depart from this settled analysisand <strong>in</strong>vite judicial super<strong>in</strong>tendence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions’educational objectives. Rather than focus analysison whether the means chosen fit the articulatededucational goals, she would change the focus <strong>of</strong>judicial scrut<strong>in</strong>y <strong>to</strong> the goals themselves—ask<strong>in</strong>gcourts <strong>to</strong> supervise and supersede educa<strong>to</strong>rs’ contextspecificeducational judgments. That approachwould be at odds with the longstand<strong>in</strong>g beneficialtradition <strong>of</strong> governmental forbearance <strong>in</strong> Americanhigher education, and should be rejected.ARGUMENTI. THE INTEREST IN STUDENTDIVERSITY IS EVEN MORECOMPELLING NOW THAN IT WAS ADECADE AGO.This <strong>Court</strong> held <strong>in</strong> Grutter that obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g theeducational benefits that flow from a diverse studentbody is a compell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest that can justify the

4narrowly tailored consideration <strong>of</strong> race <strong>in</strong> collegeadmissions. That hold<strong>in</strong>g was prescient. In an<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong>terconnected world, diversity <strong>in</strong>higher education is now more urgent than ever.A. Student Diversity Is A Compell<strong>in</strong>gInterest.This <strong>Court</strong> has long recognized that the EqualProtection Clause does not categorically prohibitcolleges and universities from consider<strong>in</strong>g race <strong>in</strong>admissions. In Regents <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>California v. Bakke, the <strong>Court</strong> reversed an <strong>in</strong>junctionbarr<strong>in</strong>g the State from “ever consider<strong>in</strong>g the race <strong>of</strong>any applicant.” 438 U.S. 265, 320 (1978) (op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>of</strong>the <strong>Court</strong>). Higher education <strong>in</strong>stitutions, the <strong>Court</strong>expla<strong>in</strong>ed, have a “substantial <strong>in</strong>terest thatlegitimately may be served by a properly devisedadmissions program <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g the competitiveconsideration <strong>of</strong> race and ethnic orig<strong>in</strong>.” Id.The <strong>Court</strong> elaborated twenty-five years later <strong>in</strong>Grutter. At issue was the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> MichiganLaw School’s use <strong>of</strong> race as a means <strong>to</strong> “obta<strong>in</strong>[ ] ‘theeducational benefits that flow from a diverse studentbody.’ ” 539 U.S. at 328 (citation omitted). The LawSchool expla<strong>in</strong>ed that student body diversity was “ ‘<strong>of</strong>paramount importance <strong>in</strong> the fulfillment <strong>of</strong> itsmission.’ ” Br. for Respondents <strong>in</strong> No. 02-241, at 28(quot<strong>in</strong>g Bakke, 438 U.S. at 313 (op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Powell,J.)). A racially <strong>in</strong>tegrated learn<strong>in</strong>g environmenthelped its students “learn how <strong>to</strong> bridge racialdivides, work sensitively and effectively with people<strong>of</strong> different races, and simply overcome the <strong>in</strong>itialdiscomfort <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g with people that are verydifferent from themselves that is a hallmark <strong>of</strong>human nature.” Id. at 25. Those educational

5benefits, moreover, could be atta<strong>in</strong>ed only through arace-conscious admissions policy. The Law Schoolhad considered a number <strong>of</strong> race-neutral means <strong>of</strong>assembl<strong>in</strong>g a racially diverse student body, butconcluded that all were “demonstrably unworkableor would substitute a different <strong>in</strong>stitutional missionfor the one that the Law School has chosen.” Id. at33.This <strong>Court</strong> upheld the Law School’s admissionspolicy and endorsed the pursuit <strong>of</strong> diversity <strong>in</strong> highereducation. Echo<strong>in</strong>g Justice Powell’s Bakke op<strong>in</strong>ion,the <strong>Court</strong> held that higher education <strong>in</strong>stitutionshave a compell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> “obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g theeducational benefits that flow from a diverse studentbody.” Grutter, 539 U.S. at 343; see also Bakke, 438U.S. at 314 (op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Powell, J.) (“the <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>of</strong>diversity is compell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the context <strong>of</strong> a university’sadmissions program”). Those benefits, the <strong>Court</strong>recognized, are “substantial.” Grutter, 539 U.S. at330. “[N]umerous studies show that student bodydiversity promotes learn<strong>in</strong>g outcomes, * * * ‘betterprepares students for an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly diverseworkforce and society, and better prepares them aspr<strong>of</strong>essionals.’ ” Id. (citation omitted). 2 Diversity2 Research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs that support this conclusion have grownmore robust s<strong>in</strong>ce Grutter was decided. See, e.g., A.L. An<strong>to</strong>nioet al., Approach<strong>in</strong>g Diversity Work <strong>in</strong> the <strong>University</strong>: Lessonsfrom an American Context, <strong>in</strong> As the World Turns: Implications<strong>of</strong> Global Shifts <strong>in</strong> Higher Education for Theory, Research andPractice 371–401 (Walter R. Allen et al. eds. 2012); S. Hurtado& L. D’Angelo, L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g Diversity and Civic-M<strong>in</strong>ded Practiceswith Student Outcomes: New Evidence from National Surveys,98 Liberal Education 2 (2012); N. Bowman, College DiversityExperiences and Cognitive Development: A Meta-Analysis, 80Review <strong>of</strong> Educational Research 4 (2010); N. Denson & M.J.Chang, Racial Diversity Matters: The Impact <strong>of</strong> Diversity-

6also promotes cross-racial understand<strong>in</strong>g, helps <strong>to</strong>break down stereotypes, and enables students <strong>to</strong>better understand those who are different. Id. Toseek these benefits through diversity is properlyunders<strong>to</strong>od <strong>to</strong> be at the core <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions’ academicmission. Id. at 329.As the Grutter <strong>Court</strong> observed, the educationalbenefits <strong>of</strong> diversity are “not theoretical but real.”Id. at 330. American bus<strong>in</strong>esses emphasized that“the skills needed <strong>in</strong> <strong>to</strong>day’s <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly globalmarketplace can only be developed through exposure<strong>to</strong> widely diverse people, cultures, ideas, andviewpo<strong>in</strong>ts.” Id. Retired military leaders expla<strong>in</strong>edthat national security depends on the ability <strong>to</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>a “highly qualified, racially diverse <strong>of</strong>ficer corps.” Id.at 330-331. And “[e]ffective participation bymembers <strong>of</strong> all racial and ethnic groups <strong>in</strong> the civiclife <strong>of</strong> our Nation is essential if the dream <strong>of</strong> oneNation, <strong>in</strong>divisible, is <strong>to</strong> be realized.” Id. at 332.Although the Grutter <strong>Court</strong> canvassed theevidence demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g the benefits <strong>of</strong> diversity <strong>in</strong>higher education, it did not purport <strong>to</strong> weigh thatevidence de novo. Such an exercise would have beenmisguided, for judges are ill-equipped <strong>to</strong> assess themerits <strong>of</strong> particular educational approaches. SeeRegents <strong>of</strong> Univ. <strong>of</strong> Mich. v. Ew<strong>in</strong>g, 474 U.S. 214, 226(1985) (courts are not “suited <strong>to</strong> evaluate thesubstance <strong>of</strong> the multitude <strong>of</strong> academic decisions thatare made daily by faculty members <strong>of</strong> publicRelated Student Engagement and Institutional Context, 46American Educational Research Journal 322 (2008); N.Gottfredson et al., Does Diversity at Undergraduate InstitutionsInfluence Student Outcomes?, 1 Journal <strong>of</strong> Diversity <strong>in</strong> HigherEducation 80 (2008).

7educational <strong>in</strong>stitutions—decisions that require ‘anexpert evaluation <strong>of</strong> cumulative <strong>in</strong>formation and[are] not readily adapted <strong>to</strong> the procedural <strong>to</strong>ols <strong>of</strong>judicial or adm<strong>in</strong>istrative decisionmak<strong>in</strong>g’ ” (citationomitted)). The universities themselves have the“experience and expertise” <strong>to</strong> make educationaljudgments. Grutter, 539 U.S. at 333. Accord<strong>in</strong>gly,the <strong>Court</strong> deferred <strong>to</strong> the Law School’s judgment thatatta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g student body diversity was essential <strong>to</strong> itseducational mission. Id. at 328.Judicial deference <strong>to</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions’ educationaljudgments was particularly appropriate <strong>in</strong> light <strong>of</strong>the “special niche” universities occupy <strong>in</strong> theAmerican constitutional tradition. Id. at 329. Theconstitution protects universities’ freedom <strong>to</strong> def<strong>in</strong>eand pursue educational goals. See, e.g., Ew<strong>in</strong>g, 474U.S. at 225; Board <strong>of</strong> Cura<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> Univ. <strong>of</strong> Mo. v.Horowitz, 435 U.S. 78, 96 n.6 (1978); Bakke, 438 U.S.at 319 n.53 (op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Powell, J.). And academicfreedom extends beyond scholarship <strong>to</strong> governanceby the academies themselves, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g control overthe composition <strong>of</strong> the student body. Grutter, 539U.S. at 329 (cit<strong>in</strong>g Bakke, 438 U.S. at 312 (op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>of</strong>Powell, J.)); see also Edwards v. California Univ. <strong>of</strong>Penn., 156 F.3d 488, 492 (3d Cir. 1998) (Ali<strong>to</strong>, J.).Constitutionally <strong>in</strong>formed pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>of</strong> academicfreedom “provide a basis for the <strong>Court</strong>’s acceptance <strong>of</strong>a university’s considered judgment that racialdiversity among students can further its educationaltask, when supported by empirical evidence.”Grutter, 539 U.S. at 387-388 (Kennedy, J.,dissent<strong>in</strong>g). These time-honored pr<strong>in</strong>ciples buttressGrutter’s core hold<strong>in</strong>g: Obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the educationalbenefits that flow from student body diversity is a

8compell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest that justifies the narrowlytailored use <strong>of</strong> race <strong>in</strong> college admissions decisions.B. Student Diversity Is Acutely NeededToday.1. Students Must Be Equipped ToNavigate An Interconnected World.Developments s<strong>in</strong>ce this <strong>Court</strong> decided Grutterunderscore the key role <strong>of</strong> diversity <strong>in</strong> Americanhigher education. Today more than ever before,<strong>in</strong>dividuals and organizations are l<strong>in</strong>ked around theworld. Trade, f<strong>in</strong>ance, and media are <strong>in</strong>ternational<strong>in</strong> scope. The ever-thicken<strong>in</strong>g web <strong>of</strong> economic,political, and social ties between nations makes<strong>in</strong>teraction among people <strong>of</strong> different backgroundsand cultures a common occurrence. See Axel Dreher,KOF Swiss Economic Institute, KOF Index <strong>of</strong>Globalization (Mar. 16, 2012).The United States is more racially and ethnicallydiverse than ever. Mitra Toossi, Labor ForceProjections <strong>to</strong> 2020: A More Slowly Grow<strong>in</strong>gWorkforce, Monthly Labor Review 43 (Jan. 2012).The trend is likely <strong>to</strong> accelerate <strong>in</strong> com<strong>in</strong>g years.Most American babies are non-white, and half thepopulation will be racial and ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority groupmembers by mid-century. Press Release, UnitedStates Census Bureau, Most Children Younger ThanAge 1 Are M<strong>in</strong>orities (May 17, 2012); Sylvia Hurtado,L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g Diversity with the Educational and CivicMissions <strong>of</strong> Higher Education, 30 The Review <strong>of</strong>Higher Education 185, 187 (2007). As the Brook<strong>in</strong>gsInstitution’s senior demographer expla<strong>in</strong>ed, theseprojections anticipated “the more globalizedmultiethnic country that we are becom<strong>in</strong>g.” Sabr<strong>in</strong>a

9Tavernise, Whites Account for Under Half <strong>of</strong> Births<strong>in</strong> U.S., N.Y. Times, May 17, 2012, at A1.In the last two decades, higher education itself hasbecome pr<strong>of</strong>oundly more global. More foreignstudents seek <strong>to</strong> study at U.S. colleges anduniversities: the State Department issued over400,000 student visas <strong>in</strong> 2010—up more than 70percent s<strong>in</strong>ce 1992. U.S. Dep’t <strong>of</strong> State, Report <strong>of</strong> theVisa Office, Classes <strong>of</strong> Nonimmigrants Issued Visas(2010). American students <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly desire <strong>to</strong>study abroad as well. “Study abroad by studentsenrolled <strong>in</strong> U.S. higher education has more thantripled over the past two decades,” and <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong>less traditional dest<strong>in</strong>ations like India and Brazilhas dramatically <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> recent years. PressRelease, U.S. Dep’t <strong>of</strong> State & Institute <strong>of</strong> Int’l Educ.,Study Abroad by U.S. Students Rose <strong>in</strong> 2009/10 withMore Students Go<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> Less TraditionalDest<strong>in</strong>ations (Nov. 14, 2011). Universities<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly are cross<strong>in</strong>g borders—a much-noteddevelopment <strong>of</strong> the past decade. As <strong>of</strong> 2009, 78 U.S.colleges and universities had established branchcampuses abroad, located from Ch<strong>in</strong>a and S<strong>in</strong>gapore<strong>to</strong> the Middle East. Scott Jaschik, InternationalCampuses on the Rise, Inside Higher Ed, Sept. 3,2009; see also American Council on Educ., U.S.Branch Campuses Abroad (Sept. 2009).To equip them <strong>to</strong> navigate <strong>to</strong>day’s and <strong>to</strong>morrow’s<strong>in</strong>terconnected world, universities must stimulatestudents’ thirst for the new and unfamiliar. Studentbody diversity catalyzes the explora<strong>to</strong>ry spirit: “Theexperience <strong>of</strong> arriv<strong>in</strong>g on a campus <strong>to</strong> live and studywith classmates from a diverse range <strong>of</strong> backgroundsis essential <strong>to</strong> students’ tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for this new world,

10nurtur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> them an <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ct <strong>to</strong> reach out <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> the comforts <strong>of</strong> what seems natural orfamiliar.” Lee C. Boll<strong>in</strong>ger, Why Diversity Matters,Chronicle <strong>of</strong> Higher Education (June 1, 2007).This acquired aff<strong>in</strong>ity for the unfamiliar enablesstudents <strong>to</strong> contribute <strong>to</strong> economic, scientific, andsocial progress, and <strong>to</strong> function <strong>in</strong> the globaleconomy. A purpose <strong>of</strong> higher education is <strong>to</strong> equippr<strong>of</strong>essionals and bus<strong>in</strong>ess leaders <strong>to</strong> <strong>in</strong>teract withdiverse cus<strong>to</strong>mers, clients, co-workers, and bus<strong>in</strong>esspartners. See Raymond V. Gilmart<strong>in</strong>, Diversity andCompetitive Advantage at Merck, Harv. Bus. Rev.146 (Jan. - Feb. 1999). Students who have had scant<strong>in</strong>teraction with peers <strong>of</strong> different races andethnicities are hampered when they graduate <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> anation <strong>in</strong> which m<strong>in</strong>orities generate more than $600billion <strong>in</strong> purchas<strong>in</strong>g power, and a world that isirreversibly <strong>in</strong>terdependent. As one lead<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>essexecutive has put it, “[o]ur success as a globalcommunity is as dependent on utiliz<strong>in</strong>g the wealth <strong>of</strong>backgrounds, skills and op<strong>in</strong>ions that a diverseworkforce <strong>of</strong>fers, as it is on raw materials, technologyand processes.” William G. Bowen & Derek Bok, TheShape <strong>of</strong> the River 12 (1998) (quot<strong>in</strong>g Robert J.Ea<strong>to</strong>n, Chairman and CEO <strong>of</strong> Chrysler Corporation).If the United States is <strong>to</strong> be the world’s economicpace-setter, colleges cannot send students <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> thatworld wear<strong>in</strong>g bl<strong>in</strong>ders. So, <strong>to</strong>o, <strong>in</strong> fields such aslaw, the natural sciences, and medic<strong>in</strong>e, where<strong>in</strong>ternational collaboration <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly is basic,students <strong>to</strong>day must receive direct experience withpeople <strong>of</strong> different races and ethnicities. Theycannot adequately acquire it from books, and theywill sorely need it. See Arthur H. Comp<strong>to</strong>n,

11Foreword <strong>to</strong> Hus<strong>to</strong>n Smith, The Purposes <strong>of</strong> HigherEducation xiv (1955).2. The Educational Benefits DiversityConfers Rema<strong>in</strong> Essential To HigherEducation.Diversity prepares students <strong>to</strong> engage with themodern world, but that is not its only benefit.Diversity serves time-honored, <strong>in</strong>dispensable goals <strong>of</strong>higher education. It <strong>in</strong>spires students <strong>to</strong> lead “theexam<strong>in</strong>ed life;” it prepares them <strong>to</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> therobust democracy that is their <strong>in</strong>heritance; and itenables them <strong>to</strong> overcome barriers that separatethem from one another, divide them from the worldthey need <strong>to</strong> know, and block their <strong>in</strong>tellectualdevelopment.1. A venerable purpose <strong>of</strong> higher education is <strong>to</strong>foster “the exam<strong>in</strong>ed life.” That is the focus <strong>of</strong>educa<strong>to</strong>rs who view higher learn<strong>in</strong>g as desirable forits own sake, apart from its economic utility. SeeRobert M. Hutch<strong>in</strong>s, The Higher Learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>America (Transaction Publishers 1995) (1936);J.H.C. Newman, The Idea <strong>of</strong> a <strong>University</strong> (M.J.Svaglic ed., Univ. <strong>of</strong> Notre Dame Press 1982) (1873).These educa<strong>to</strong>rs consider the crucial work <strong>of</strong> highereducation <strong>to</strong> be challeng<strong>in</strong>g students’ embeddedpreconceptions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>of</strong>ten, their most deeplyheldvalues; for only by critically exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g themcan students gauge rationally whether theirpreconceptions are worthy. Educa<strong>to</strong>rs who hold thisview emphasize th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g logically, expos<strong>in</strong>g fallacy,and test<strong>in</strong>g assumption through rigorous question<strong>in</strong>gand dialectic, all <strong>in</strong> order <strong>to</strong> develop students’ powers<strong>of</strong> reason.

12Diversity contributes vitally <strong>to</strong> the process <strong>of</strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g, on which the powers <strong>of</strong> reason depend. Aprecept <strong>of</strong> developmental psychology is that we learnby formulat<strong>in</strong>g, revis<strong>in</strong>g, and ref<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g conceptions <strong>of</strong>the world each time we encounter new facts, beliefs,experiences, and viewpo<strong>in</strong>ts. Peter B. Pufall, TheDevelopment <strong>of</strong> Thought: On Perceiv<strong>in</strong>g andKnow<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong> Robert Shaw & John Bransford,Perceiv<strong>in</strong>g, Act<strong>in</strong>g, and Know<strong>in</strong>g: Toward anEcological Psychology 173-174 (1977). Faced withnew <strong>in</strong>formation, students either assimilate it <strong>to</strong> fitthe exist<strong>in</strong>g conception, or revise the conception <strong>to</strong>accommodate the new <strong>in</strong>formation. This“disequilibration,” as Jean Piaget called it, and thesubsequent res<strong>to</strong>ration <strong>of</strong> cognitive balance, forcelearners <strong>to</strong> ref<strong>in</strong>e their th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. Piaget taught that“disequilibration” experiences have greatest impactwhen they come from “social <strong>in</strong>teraction.” JeanPiaget, Piaget’s Theory, <strong>in</strong> 1 Carmichael’s Manual <strong>of</strong>Child Psychology (P. H. Mussen ed., 3d ed. Wiley1970). A student, confronted by a peer who has anew or unexpected way <strong>of</strong> look<strong>in</strong>g at the world,meets that perspective as an equal, and can exploreand absorb it more fully than if merely <strong>in</strong>formed <strong>of</strong> it<strong>in</strong>, for example, a lecture. See, e.g., Diane N. Ruble,A Phase Model <strong>of</strong> Transitions: Cognitive andMotivational Consequences, 26 Advances <strong>in</strong>Experimental Social Psych. 163, 171 (1994). Collegesand universities supply and catalyze “that collisionwhich is obta<strong>in</strong>ed only <strong>in</strong> society and by which aknowledge <strong>of</strong> the world and its manners is bestacquired.” F.W. Garforth, Educative Democracy:John Stuart Mill on Education <strong>in</strong> Society 164 (1980)(cit<strong>in</strong>g David Ricardo).

13These bedrock pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>of</strong> developmentalpsychology, <strong>to</strong> which educa<strong>to</strong>rs at all levelssubscribe, teach that expos<strong>in</strong>g students <strong>to</strong> an array<strong>of</strong> peer life experiences and perspectives is critical <strong>to</strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g. The familiar is less valuable; it tendsmerely <strong>to</strong> re<strong>in</strong>force preconception. But the new anddifferent are food for <strong>in</strong>tellectual growth. Studentdiversity provides all learners opportunities <strong>to</strong>develop their <strong>in</strong>tellects, by exposure <strong>to</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>glycomplex and nuanced models presented by peers.These new perspectives and experiences areespecially educational when encountered <strong>in</strong> direct<strong>in</strong>teraction with a peer, because peer encountersentail the give-and-take and the emotional processesthat promote complex th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g.A diverse campus thus awakens students from thesleepy “unexam<strong>in</strong>ed life” <strong>of</strong> which Socrates warned.Interaction among students from diversebackgrounds exposes each <strong>to</strong> a broader array <strong>of</strong>vantage po<strong>in</strong>ts from which <strong>to</strong> view his or her ownvalues than does <strong>in</strong>teraction among like-m<strong>in</strong>dedstudents whose experiences are similar. Of course,students will not and should not always accept newperspectives and abandon their own. Highereducation teaches students <strong>to</strong> employ reason <strong>to</strong>decide for themselves which <strong>of</strong> their beliefs <strong>to</strong> reta<strong>in</strong>,and which <strong>to</strong> cast aside <strong>in</strong> favor <strong>of</strong> other discoveredtruths. And students <strong>in</strong> diverse <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>of</strong>tenlearn that anticipated differences <strong>in</strong> perspectives orviews do not exist, or do not correlate as expectedwith race or ethnicity. Preconception is therebydispelled, and stereotype is thereby rebutted.2. Another purpose <strong>of</strong> higher education is <strong>to</strong>prepare students for citizenship. An educated

14citizenry is the predicate <strong>of</strong> a thriv<strong>in</strong>g democracy.Mueller v. Allen, 463 U.S. 388, 395 (1983); DeRolphv. State, 677 N.E.2d 733, 736 (Ohio), clarified, 678N.E.2d 886 (Ohio 1997). Colleges and universitiesseek <strong>to</strong> develop students’ capacity not only <strong>to</strong>comprehend and reach their own <strong>in</strong>formed views onissues <strong>of</strong> public import, but also <strong>to</strong> engage <strong>in</strong>deliberative aspects <strong>of</strong> democracy—<strong>to</strong> <strong>in</strong>teract anddebate with other citizens, listen with an open m<strong>in</strong>d,and persuade—so as <strong>to</strong> achieve collective solutions <strong>to</strong>public problems. See Nat’l Task Force on CivicLearn<strong>in</strong>g and Democratic Engagement, A CrucibleMoment: College Learn<strong>in</strong>g and Democracy’s Future(2012). The “Constitution presupposes the existence<strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>formed citizenry prepared <strong>to</strong> participate <strong>in</strong>governmental affairs.” Board <strong>of</strong> Educ., Island TreesUnion Free Sch. Dist. No. 26 v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853,876 (1982) (Blackmun, J., concurr<strong>in</strong>g). Governmenthas long conceived higher education as an eng<strong>in</strong>e <strong>to</strong>ready students for citizenship <strong>in</strong> “a common vessel.”See David J. Barron, The Promise <strong>of</strong> Cooley’s City:Traces <strong>of</strong> Local Constitutionalism, 147 U. Pa. L. Rev.487, 543-544 (1999).A diverse student body demonstrably preparesstudents for citizenship. Diversity <strong>of</strong> backgroundstends <strong>to</strong> broaden and give more credibility <strong>to</strong> campusdiscussion and debate, by expos<strong>in</strong>g students <strong>to</strong>perspectives borne <strong>of</strong> different life experiences. Suchexposure makes students better-<strong>in</strong>formed voters,jurors, school board and neighborhood associationmembers, and engaged participants <strong>in</strong> consideration<strong>of</strong> public affairs. Effective civic participationdepends on ability <strong>to</strong> work with those whosebackgrounds are different; students educated <strong>in</strong> adiverse sett<strong>in</strong>g are better prepared <strong>to</strong> work with

15fellow citizens from all walks <strong>of</strong> life. “Learn<strong>in</strong>g is notmerely the acquir<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> mastery over <strong>in</strong>tellectualsubject matter * * *. [I]n our schools and colleges,every citizen <strong>of</strong> the world should become ‘at home’ <strong>in</strong>the human ‘state.’ ” Alexander Meikeljohn,Education Between Two Worlds 277 (1942).Student diversity <strong>in</strong> higher education thus takesstudentsout <strong>of</strong> the narrow circle <strong>of</strong> personal and familyselfishness * * * accus<strong>to</strong>m<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>to</strong> thecomprehension <strong>of</strong> jo<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong>terests, the managemen<strong>to</strong>f jo<strong>in</strong>t concerns—habituat<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>to</strong> act frompublic or semi-public motives and guide theirconduct by aims which unite <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> isolat<strong>in</strong>gthem from one another.John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, <strong>in</strong> Three Essays 134(Oxford Univ. Press 1975) (1859).3. A third aim <strong>of</strong> higher education is <strong>to</strong> enablestudents <strong>to</strong> overcome barriers that separate themfrom one another, divide them from the world theyneed <strong>to</strong> know, and impede their <strong>in</strong>tellectual growth.The develop<strong>in</strong>g theme <strong>of</strong> American higher educationfrom the start has been <strong>to</strong> eradicate divisions anddifferences that limit students, and thereby <strong>to</strong> teachcritical self-reflection and impart knowledge. Thattheme, perhaps more than any other, has def<strong>in</strong>ed therole and achievement <strong>of</strong> higher education <strong>in</strong> oursociety.“The ‘American people have always regardededucation and [the] acquisition <strong>of</strong> knowledge asmatters <strong>of</strong> supreme importance.’ ” Plyler v. Doe, 457U.S. 202, 221 (1982) (citation omitted). TheFounders saw higher education as essential <strong>to</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>

16the nation’s leaders who, John Adams held, shouldbe recruited not from among “the rich or the poor,the high-born or the low-born, the <strong>in</strong>dustrious or theidle; but all those who have received a liberaleducation.” Frank Donovan ed., The John AdamsPapers 182 (1965). They believed that education<strong>in</strong>stitutions must build and re<strong>in</strong>force bonds amongcitizens. Even <strong>in</strong> an era when college was accessibleonly <strong>to</strong> the well-placed few, they advocated commonschools <strong>to</strong> br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong>gether the nation’s young and<strong>in</strong>still a sense <strong>of</strong> national community. NoahWebster, On the Education <strong>of</strong> Youth <strong>in</strong> America(1790), <strong>in</strong> Essays on Education <strong>in</strong> the Early Republic66 (Frederick Rudolph ed., 1965); Carl F. Kaestle,Pillars <strong>of</strong> the Republic: Common Schools andAmerican Society 1780-1860, at 7 (Eric Foner ed.1983) (quot<strong>in</strong>g Benjam<strong>in</strong> Rush).Removal <strong>of</strong> barriers is thus the essence <strong>of</strong>American higher education, necessary both forpersonal growth and the cont<strong>in</strong>ued growth <strong>of</strong> theNation. “A democracy is more than a form <strong>of</strong>government; it is primarily a mode <strong>of</strong> associatedliv<strong>in</strong>g” that depends on “communicated experience.”John Dewey, Democracy and Education 101 (FreePress 1966) (1916). And we demand even more <strong>of</strong>graduates now, as the nation “break[s] down * * *barriers <strong>of</strong> class, race, and national terri<strong>to</strong>ry,”because such a society produces “more numerous andmore varied po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> contact” and “a greaterdiversity <strong>of</strong> stimuli <strong>to</strong> which an <strong>in</strong>dividual has <strong>to</strong>respond.” Id. Inculcat<strong>in</strong>g not only “an ability” butalso “an <strong>in</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ation” “<strong>to</strong> serve mank<strong>in</strong>d, one’scountry, friends and family,” wrote Frankl<strong>in</strong>, is “thegreat Aim and End <strong>of</strong> all learn<strong>in</strong>g.” Benjam<strong>in</strong>

17Frankl<strong>in</strong>, Proposals Relat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> the Education <strong>of</strong>Youth <strong>in</strong> Pennsylvania 30 (1749, repr<strong>in</strong>t 1931).II.HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONSNEED FLEXIBILITY TO DEFINE ANDATTAIN DIVERSITY.Diversity is thus <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> achievement <strong>of</strong> basicpurposes <strong>of</strong> higher education, and appropriatediversity for a particular <strong>in</strong>stitution is a matter <strong>of</strong>educational judgment. But Petitioner would havecourts not only scrut<strong>in</strong>ize the means <strong>in</strong>stitutions use<strong>to</strong> atta<strong>in</strong> diversity—a familiar judicial role—but alsosecond-guess a university’s considered judgmentabout what type <strong>of</strong> diversity <strong>to</strong> pursue <strong>in</strong> light <strong>of</strong> itsdist<strong>in</strong>ct educational mission.This <strong>Court</strong> should not displace a university’seducational judgment with a cramped prescription <strong>of</strong>what k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> diversity and how much diversity an<strong>in</strong>stitution needs. To do so would represent a sharpbreak from the longstand<strong>in</strong>g and salutary tradition<strong>of</strong> governmental forbearance <strong>in</strong> higher education.Institutional pluralism, the hallmark <strong>of</strong> Americanhigher education, is traceable <strong>to</strong> that forbearanceand has allowed our colleges and universities <strong>to</strong>become the envy <strong>of</strong> the world. To impose a s<strong>in</strong>gledef<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> diversity on all <strong>of</strong> higher educationwould conflict with the <strong>Court</strong>’s precedents andunderm<strong>in</strong>e those benefits.

18A. American Higher Education Thrives OnPluralism.1. American Higher Education IsCharacterized By The Variety OfInstitutional Missions.American higher education is preem<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong> theworld and a beacon <strong>to</strong> other countries. Most <strong>of</strong> theworld’s lead<strong>in</strong>g universities are here. See ShanghaiJiao Tong <strong>University</strong>, Academic Rank<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> WorldUniversities: 2011; William G. Bowen et al., Equityand Excellence <strong>in</strong> American Higher Education 54(2005). Our universities “produce a very highproportion <strong>of</strong> the most important fundamentalknowledge and practical research discoveries <strong>in</strong> theworld”; the scholars and scientists they tra<strong>in</strong> areglobal leaders <strong>in</strong> their fields. Jonathan R. Cole, TheGreat American <strong>University</strong> 5 (2010). Our nation<strong>in</strong>vests <strong>in</strong> higher education more resources perstudent than any other. Organization for Econ.Cooperation & Dev., Education at a Glance: OECDIndica<strong>to</strong>rs 209 (2011). S<strong>in</strong>ce World War II, “by awide marg<strong>in</strong>” pr<strong>of</strong>essors at American universitieshave been awarded more Nobel prizes for physics,chemistry, medic<strong>in</strong>e, and economics than any othercountry. Jon Bruner, American Leadership <strong>in</strong>Science, Measured <strong>in</strong> Nobel Prizes, Forbes.com(Oct. 5, 2011). Graduates <strong>of</strong> American colleges anduniversities serve <strong>in</strong> leadership roles <strong>in</strong> this andother countries <strong>to</strong> an extent unequalled by anynation <strong>in</strong> his<strong>to</strong>ry. E.g., Uri Friedman & KedarPavgi, Head <strong>of</strong> the Class?, Foreign Policy (Nov. 18,2011); Menachem Wecker, Where the Fortune 500CEOs Went <strong>to</strong> School, U.S. News & World Report(May 14, 2012).

19The hallmark <strong>of</strong> American higher education is itsunique pluralism. In contrast <strong>to</strong> most othercountries, <strong>in</strong> the United States the path <strong>of</strong> highereducation is not directed from a central m<strong>in</strong>istry.Higher education here, allowed <strong>to</strong> evolve organically,is now characterized by a rich diversity <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>stitutions: community colleges and four-year<strong>in</strong>stitutions, public and private universities, nonpr<strong>of</strong>itand for-pr<strong>of</strong>it colleges, religious-affiliated andsecular <strong>in</strong>stitutions, vocational and liberal artscolleges. This diversity is matched by an equallybroad array <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional missions—from oneuniversity’s commitment <strong>to</strong> religious leadership, <strong>to</strong> asmall college’s focus on the student’s self-governanceand manual labor, <strong>to</strong> a lead<strong>in</strong>g technology <strong>in</strong>stitute’sengagement with the cutt<strong>in</strong>g edge <strong>of</strong> physicalscience.The pluralism <strong>of</strong> American higher education fostersa healthy competition among <strong>in</strong>stitutions that is key<strong>to</strong> the success <strong>of</strong> the entire system. See HenryRosovsky, Highest Education, 197 The New Republic13 (1987). Colleges and universities <strong>in</strong> the UnitedStates compete for students, faculty, and resources.They strive <strong>to</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>guish themselves and <strong>to</strong> <strong>of</strong>feradvantages over their peer <strong>in</strong>stitutions, test<strong>in</strong>g neweducational strategies and learn<strong>in</strong>g from oneanother. When an <strong>in</strong>stitution identifies a successfulstrategy, others adapt it; when an <strong>in</strong>stitutionstumbles, others draw lessons. Yet each <strong>in</strong>stitutionultimately forges its own path <strong>in</strong> light <strong>of</strong> its dist<strong>in</strong>ctmission. These efforts have led American collegesand universities <strong>to</strong> become, like the Statesthemselves, “labora<strong>to</strong>ries for experimentation <strong>to</strong>devise various solutions where the best solution isfar from clear.” United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549,

20581 (1995) (Kennedy, J., concurr<strong>in</strong>g). Their<strong>in</strong>novation drives the rich variety with<strong>in</strong> Americanhigher education and is responsible for itsunparalleled success.2. The Government Has RepeatedlyEndorsed The Value Of ADecentralized Higher EducationSystem In Which Institutions PursueTheir Respective Missions In TheirRespective Ways.These features <strong>of</strong> American education did not ariseby accident. A long tradition, nearly unique amongnations, <strong>of</strong> government forbearance with respect <strong>to</strong>educa<strong>to</strong>rs’ judgment has figured prom<strong>in</strong>ently <strong>in</strong> thisvibrant system. S<strong>in</strong>ce the found<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the Republic,this <strong>Court</strong>, the Executive and Congress <strong>in</strong> keyjudicial and policy decisions repeatedly have opted <strong>to</strong>grant colleges and universities more, not less,authority <strong>in</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g higher educationpractices and pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. See Mart<strong>in</strong> Trow,Federalism <strong>in</strong> American Higher Education, <strong>in</strong> HigherLearn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> America 1980-2000 (Arthur Lev<strong>in</strong>e ed.,1993); John S. Brubacher & Willis Rudy, HigherEducation <strong>in</strong> Transition: A His<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> AmericanColleges and Universities 9 (4th ed. 1997) (1958).American universities are accorded “greater freedomfrom government supervision than higher educationenjoys <strong>in</strong> any other major country <strong>of</strong> the world.”Derek Bok, Higher Learn<strong>in</strong>g 14 (1986).The <strong>Court</strong> long has championed colleges’ anduniversities’ authority <strong>to</strong> make educationaljudgments. In Trustees <strong>of</strong> Dartmouth College v.Woodward, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 518 (1819), forexample, the <strong>Court</strong> confronted whether a state

21possessed power <strong>to</strong> alter a college charter, and heldthat a college’s board <strong>of</strong> trustees was better suitedthan the government <strong>to</strong> govern it. Chief JusticeMarshall’s op<strong>in</strong>ion acknowledged that a collegewould sometimes err, but, he expla<strong>in</strong>ed, decisions <strong>in</strong>educational matters should be made by theeduca<strong>to</strong>rs, not the legislature. See 1 James Kent,Commentaries on American Law 416-417 (O.W.Holmes ed., 12th ed. 1873).The <strong>Court</strong> has proceeded <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g twocenturies <strong>to</strong> re<strong>in</strong>force colleges’ and universities’authority <strong>in</strong> the educational sphere. In the decadesfollow<strong>in</strong>g the Dartmouth College decision, tensionsarose between legislatures and higher education<strong>in</strong>stitutions over questions <strong>of</strong> taxation and contract.Could a state legislature lawfully tax a universitywhose charter exempted it from tax? More than thepower <strong>to</strong> tax was at stake, as that power implicatedbroader government <strong>in</strong>fluence over higher education.Cf. M’Culloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat) 316,431 (1819). The seem<strong>in</strong>gly unassailable argumentthat a legislature should not be able <strong>to</strong> “barga<strong>in</strong>away forever the tax<strong>in</strong>g power <strong>of</strong> the State” weighed<strong>in</strong> favor <strong>of</strong> governmental authority. Wash<strong>in</strong>g<strong>to</strong>nUniv. v. Rouse, 75 U.S. (8 Wall.) 439, 443 (1869)(Miller, J., dissent<strong>in</strong>g). Yet the <strong>Court</strong> upheld the<strong>in</strong>stitutions’ au<strong>to</strong>nomy, see, e.g., id. at 440;<strong>University</strong> v. People, 99 U.S. 309, 310, 325 (1878), <strong>in</strong>the expectation that they would act <strong>in</strong> accordancewith their educational purposes. Wash<strong>in</strong>g<strong>to</strong>n Univ.,75 U.S. at 440-441.In the early twentieth century, questions arose thatranged from adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> a private university’sendowment, Taylor v. Columbian Univ., 226 U.S.

22126 (1912), <strong>to</strong> a public university’s discretion <strong>to</strong>require military tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, Hamil<strong>to</strong>n v. Regents <strong>of</strong>Univ. <strong>of</strong> Cal., 293 U.S. 245 (1934). In eachcircumstance the <strong>Court</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>to</strong> substitute itsjudgment for that <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stitution. In Taylor, forexample, the <strong>Court</strong> upheld the university’sadm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> a scholarship where the charitablepurpose was accomplished “<strong>in</strong> some degree, at least.”Id. at 135.The <strong>Court</strong> extended the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>in</strong> the 20thcentury <strong>to</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terplay <strong>of</strong> constitutional due processand a university’s au<strong>to</strong>nomy over its students. InBoard <strong>of</strong> Cura<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Missouri v.Horowitz, 435 U.S. 78 (1978), the <strong>Court</strong> held that theFourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause does notrequire a public university <strong>to</strong> provide a hear<strong>in</strong>gbefore dismiss<strong>in</strong>g a student on academic grounds.Id. at 87. The <strong>Court</strong> weighed the <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong>protect<strong>in</strong>g students from arbitrary dismissal aga<strong>in</strong>st“harm <strong>to</strong> the academic environment” that wouldresult from “[j]udicial <strong>in</strong>terposition” <strong>in</strong> universityaffairs. Id. at 90-91. Although the student’s <strong>in</strong>terestwas “weighty” because she would be unable <strong>to</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>ue her medical education, id. at 100 (Marshall,J., concurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> part and dissent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> part), the<strong>Court</strong> “decl<strong>in</strong>e[d] <strong>to</strong> ignore the his<strong>to</strong>ric judgment <strong>of</strong>educa<strong>to</strong>rs” that a hear<strong>in</strong>g should not be required. Id.at 90 (op<strong>in</strong>ion for the <strong>Court</strong>). To “enlarge the judicialpresence <strong>in</strong> the academic community,” the <strong>Court</strong>said, would “risk deterioration.” The <strong>Court</strong> thusdeterm<strong>in</strong>ed not <strong>to</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervene <strong>in</strong> the academicdecision; do<strong>in</strong>g so would “raise[ ] problems * * *requir<strong>in</strong>g care and restra<strong>in</strong>t.” Id. at 90-91.

23Forbearance with respect <strong>to</strong> educational judgmentfigured <strong>in</strong> Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234,250 (1957), where a university lecturer decl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>to</strong>answer a state at<strong>to</strong>rney general’s questions aboutthe content <strong>of</strong> his lectures. The <strong>in</strong>quiry, ChiefJustice Warren said, “unquestionably was an<strong>in</strong>vasion * * * <strong>of</strong> academic freedom and politicalexpression—areas <strong>in</strong> which the government shouldbe extremely reluctant <strong>to</strong> tread. * * * To impose anystrait jacket upon the <strong>in</strong>tellectual leaders <strong>in</strong> ourcolleges and universities would imperil the future <strong>of</strong>our Nation.” Id. at 250. Justice Frankfurter <strong>in</strong>concurrence cited “ ‘four essential freedoms’ <strong>of</strong> auniversity—<strong>to</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>e for itself on academicgrounds who may teach, what may be taught, how itshall be taught, and who may be admitted <strong>to</strong> study.’ ”See Bakke, 438 U.S. at 312 (op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Powell, J.)(quot<strong>in</strong>g Sweezy, 354 U.S. at 263 (Frankfurter, J.,concurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the result)). “[W]ho may be admitted<strong>to</strong> study” is paradigmatic academic judgment. Seeid. at 312; see also id. at 405 (op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Blackmun,J.); id. at 366 n.42 (op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> Brennan, J.) (“TheRegents, not the legislature, have the general rulemak<strong>in</strong>gor policy-mak<strong>in</strong>g power with regard <strong>to</strong> the<strong>University</strong>.”).The <strong>Court</strong> further extended the forbearancepr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>in</strong> Regents <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan v.Ew<strong>in</strong>g, 474 U.S. 214 (1985), uphold<strong>in</strong>g a publicuniversity’s dismissal <strong>of</strong> a student who failed a keyexam. The court <strong>of</strong> appeals had held the decision anarbitrary deprivation <strong>of</strong> property because pla<strong>in</strong>tiffwas the only student <strong>in</strong> seven years denied anopportunity <strong>to</strong> retake the exam, and a universitypamphlet promised a retest. Id. at 221; see Ew<strong>in</strong>g v.Board <strong>of</strong> Regents <strong>of</strong> Univ. <strong>of</strong> Mich., 742 F.2d 913,

24915-916 (6th Cir. 1984). On that record, application<strong>of</strong> standards for arbitrary government action <strong>in</strong> nonuniversitycontexts might well have produced adifferent result. But the <strong>Court</strong> held the dismissal an“academic decision” and cited “[c]onsiderations <strong>of</strong>pr<strong>of</strong>ound importance [that] counsel restra<strong>in</strong>edjudicial review,” Ew<strong>in</strong>g, 474 U.S. at 225, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gthe right <strong>to</strong> decide “who may be admitted <strong>to</strong> study.”Id. at 226 n. 12. The “narrow avenue for judicialreview” the <strong>Court</strong> set focused solely on whether thedecision “[was] such a substantial departure fromaccepted academic norms as <strong>to</strong> demonstrate that the[faculty] did not actually exercise pr<strong>of</strong>essionaljudgment.” Id. at 225, 227. The <strong>Court</strong> concludedthat academic judgments “made daily by facultymembers * * * require ‘an expert evaluation <strong>of</strong>cumulative <strong>in</strong>formation and [are] not readily adapted<strong>to</strong> the procedural <strong>to</strong>ols <strong>of</strong> judicial or adm<strong>in</strong>istrativedecisionmak<strong>in</strong>g.’ ” Id. at 226 (quot<strong>in</strong>g Horowitz, 435U.S. at 89-90).The other branches <strong>of</strong> government, <strong>to</strong>o, <strong>in</strong> decisionswith pr<strong>of</strong>ound consequence for American collegesand universities, have opted <strong>to</strong> leave the conduct <strong>of</strong>higher education <strong>to</strong> educa<strong>to</strong>rs. Thus, <strong>in</strong> theAdm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> George Wash<strong>in</strong>g<strong>to</strong>n, Congressrejected establishment <strong>of</strong> a national university thatwould set federal standards for all <strong>of</strong> the newnation’s colleges. 1 Richard H<strong>of</strong>stadter and WilsonSmith eds., American Higher Education: ADocumentary His<strong>to</strong>ry 157 (1961). (Congress greeteda similar proposal by John Qu<strong>in</strong>cy Adams “with agale <strong>of</strong> laughter.” Edward H. Reisner, Antecedents <strong>to</strong>the Federal Act Concern<strong>in</strong>g Education, 11Educational Record 196, 197 (July 1930).) Had theidea <strong>of</strong> a national university carried, the United

25States likely would have developed the morecentralized, governmental control <strong>of</strong> highereducation characteristic <strong>of</strong> the European nations.The decision not <strong>to</strong> establish such an <strong>in</strong>stitution or acharter-grant<strong>in</strong>g federal m<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> education—adecision <strong>of</strong> which Chief Justice Marshall was awarewhen he addressed the Dartmouth College case—preserved the pluralism, adaptiveness, and will <strong>to</strong><strong>in</strong>novate that rema<strong>in</strong> American higher educationhallmarks. Thus Thomas Jefferson founded auniversity <strong>in</strong> Virg<strong>in</strong>ia based on the “illimitablefreedom <strong>of</strong> the human m<strong>in</strong>d * * * <strong>to</strong> follow truthwherever it may lead.” Roy J. Honeywell,Educational Works <strong>of</strong> Thomas Jefferson 99 (1931).The design <strong>of</strong> federal support <strong>to</strong> higher educationhas re<strong>in</strong>forced <strong>in</strong>stitutional authority. In the MorrillLand-Grant Act, 12 Stat. 503 (1862), Congressgranted 11,000 square miles <strong>of</strong> land <strong>to</strong> states foragricultural and mechanical arts colleges, “withoutexclud<strong>in</strong>g other scientific and classical studies.” Id.at 504. By then the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong> federal governmentabstention from judgments about the conduct <strong>of</strong>higher education was so engra<strong>in</strong>ed that PresidentBuchanan ve<strong>to</strong>ed an earlier version <strong>of</strong> the Act as anunconstitutional exercise <strong>of</strong> federal power. See CarlSwisher, American Constitutional Development 374(1943). Unquestionably the Morrill Act was atransformative assertion <strong>of</strong> federal <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> highereducation. Yet the Act imposed virtually norequirements on the type <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitution or curriculumthat could benefit from this massive grant. See 12Stat. 504; Hamil<strong>to</strong>n, 293 U.S. at 258-259 (stateaccept<strong>in</strong>g federal land-grants “rema<strong>in</strong>[ed]untrammeled by federal enactment and [was]entirely free <strong>to</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>e for itself” the content and

26objectives <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>struction). Instead <strong>of</strong> draw<strong>in</strong>g afederal bluepr<strong>in</strong>t, Congress mandated flexibility thatproduced an extraord<strong>in</strong>ary range <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions andprograms, prompt<strong>in</strong>g one educa<strong>to</strong>r <strong>to</strong> observe that “<strong>of</strong>all the good fortune which has attended the carry<strong>in</strong>gout <strong>of</strong> the act <strong>of</strong> 1862, this variety <strong>of</strong> plans andmethods <strong>in</strong> the various states was the best.” EarleD. Ross, Democracy’s College: The Land-GrantMovement <strong>in</strong> the Formative Stage 68-69 (1942)(quot<strong>in</strong>g Andrew D. White).In the most important 20th century highereducation laws, the government similarly favorededuca<strong>to</strong>rs’ authority. The first <strong>of</strong> these, theServicemen’s Readjustment Act <strong>of</strong> 1944 (known asthe GI Bill)—at the time the most far-reach<strong>in</strong>gf<strong>in</strong>ancial boost <strong>to</strong> higher education <strong>in</strong> the nation’shis<strong>to</strong>ry—aga<strong>in</strong> provided aid <strong>in</strong> a manner thatmaximized <strong>in</strong>stitutional au<strong>to</strong>nomy <strong>in</strong> the educationalrealm. See 58 Stat. 288. Congress rejected proposalsthat would have prescribed detailed standards for<strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>to</strong> receive aid, and directed that “nodepartment, agency, or <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> the UnitedStates * * * shall exercise any supervision or control,whatsoever, over * * * any educational or tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>stitution.” 58 Stat. 289. By structur<strong>in</strong>g the aidwith few prescriptions on the types <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions orprograms for which it could be used, the adoptedapproach reaffirmed the value <strong>of</strong> competition among<strong>in</strong>stitutions, each with its own educational model, asthe best way <strong>to</strong> promote quality higher education.See H.R. Rep. No. 78-1418, at 3 (1944); Trow,Federalism <strong>in</strong> Higher Education, <strong>in</strong> Higher Learn<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> America at 58-59.