(eds) (2009). The Sacred Dimension of Protected Areas - IUCN

(eds) (2009). The Sacred Dimension of Protected Areas - IUCN

(eds) (2009). The Sacred Dimension of Protected Areas - IUCN

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

264

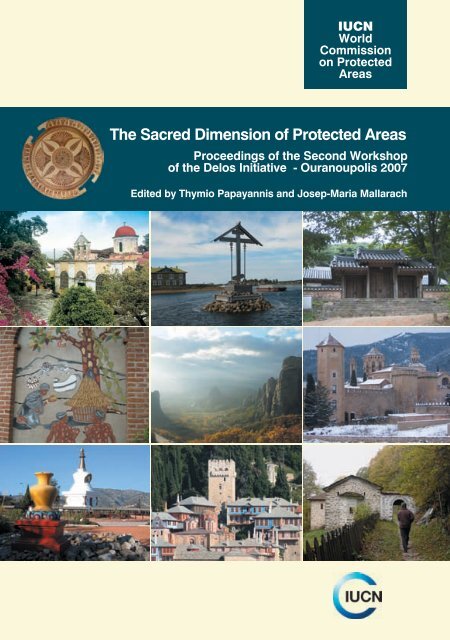

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Dimension</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Protected</strong> <strong>Areas</strong>Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Second Workshop<strong>of</strong> the Delos Initiative

<strong>The</strong> designation <strong>of</strong> geographical entities in this book and the presentation <strong>of</strong> the material do not imply the expression<strong>of</strong> any opinion whatsoever on the part <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong> or Med-INA concerning the legal status <strong>of</strong> any country,territory or area or <strong>of</strong> its authorities, or concerning the delimitation <strong>of</strong> its frontiers or boundaries.<strong>The</strong> views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong>, Med-INA, or the other participatingorganizations.Published by:Copyright:Citation:<strong>IUCN</strong>, Gland, Switzerland and the Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos(Med-INA), Athens, Greece© All the authors for their respective contributions, International Union for Conservation<strong>of</strong> Nature and Natural Resources and Med-INAPapayannis, T. and Mallarach, J.-M. (<strong>eds</strong>) (<strong>2009</strong>). <strong>The</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Dimension</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Protected</strong><strong>Areas</strong>: Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Second Workshop <strong>of</strong> the Delos Initiative – Ouranoupolis2007. Gland, Switzerland: <strong>IUCN</strong> and Athens, Greece: Med-INA. pp. 262ISBN: 978-2-8317-1166-9Cover design:Cover photos:Layout:Pavlina AlexandropoulouClockwise from top: Holy Convent <strong>of</strong> Chrysopigi, A. Davydov, K.K. Han, R. Wild, I. Lyratzaki,Archives <strong>of</strong> the Monastery <strong>of</strong> Poblet, J.M. Mallarach, B. Verschuuren, S. CatanoiuBack: J. M. MallarachPavlina AlexandropoulouTranslation into English: Michael Eleftheriou<strong>IUCN</strong> and the other participating organizations do not take any responsibility for errorsor omissions occurring in the translation into English <strong>of</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> this document whoseoriginal version is in Greek.Ôext editing:Produced by:Printed by:Available from:Michael EleftheriouMediterranean Institute for Nature and AnthroposI. Peppas A.B.E.E.<strong>IUCN</strong> (International Union for Conservation <strong>of</strong> Nature)Publications ServicesRue Mauverney 281196 GlandSwitzerlandTel +41 22 999 0000Fax+41 22 999 0020books@iucn.orgwww.iucn.org/publicationsA catalogue <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong> publications is also availableMed-INA23, Voukourestiou Street106 71 AthensGreeceTel+30 210 3600711Fax+30 210 3629338secretariat@med-ina.orgwww.med-ina.org<strong>The</strong> publication was funded by the Bodossaki Foundation and Med-INA.<strong>The</strong> text <strong>of</strong> this book has been printed on 125g matt coated environmentally-friendly paper.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Dimension</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Protected</strong> <strong>Areas</strong>Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the Second Workshop<strong>of</strong> the Delos InitiativeOuranoupolis, Greece, 24-27 October 2007Edited by Thymio Papayannis and Josep-Maria Mallarach

table <strong>of</strong> contents7 Opening messageHAH <strong>The</strong> Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I9 Opening statementsDimitrios TziritisFather Gregorios13 IntroductionThymio Papayannis and Josep-Maria Mallarach25 Part One: Analysis <strong>of</strong> case studies27 Indigenous peoples27 Power on this land; managing sacred sites at Dhimurru Indigenous <strong>Protected</strong>Area, Northeast Arnhem Land, AustraliaBas Verschuuren, Mawalan II Marika and Phil Wise47 <strong>Sacred</strong> versus secular in the San Francisco Peaks, Arizona, USAJeneda Benally and Lawrence Hamilton61 Mainstream faiths61 <strong>The</strong> National Park <strong>of</strong> the Casentine Forests, ItalyGloria Pungetti, Franco Locatelli and Father Peter Hughes67 ‘Abd al-Salâm ibn Mashîsh and Jabal La‘lâm Site, Northern MoroccoZakia Zouanat77 <strong>Sacred</strong> Mountain <strong>of</strong> Ganghwa Island, South KoreaKyung-Koo Han89 Solovetsky Islands: a holy land surrounded by the Arctic Ocean,Russian FederationAlexander N. Davydov, Ivan N. Bolotov and Galina V. Mikhailova105 Part Two: Management <strong>of</strong> monastic lands and facilities107 Mount Athos (Greece)107 <strong>The</strong> protected area <strong>of</strong> the peninsula <strong>of</strong> the Athos Holy Mountain, Halkidiki, GreeceIoannis Philippou and Konstantinos Kontos127 Landscape conservation actions on Mount Athos, Halkidiki, GreecePetros Kakouros

137 other case studies137 Buila-Vânturarit,a National Park, Valcea county, RomaniaSebastian Catanoiu153 An integrated ecological approach to monastic land:the case <strong>of</strong> the Holy Convent <strong>of</strong> Chrysopigi, Chania, Crete, GreeceMother Superior <strong>The</strong>oxeni161 Initiatives taken by the Cistercian Monastery <strong>of</strong> Poblet to improve theintegration <strong>of</strong> spiritual, cultural and environmental values, Catalonia, SpainJosep-Maria Mallarach and Lluc M. Torcal173 Rila Monastery Natural Park, BulgariaJosep-Maria Mallarach and Sebastian Catanoiu177 <strong>The</strong> inclusion <strong>of</strong> a Tibetan Buddhist perspective in the management<strong>of</strong> the property <strong>of</strong> the Sakya Tashi Ling Monastery in Garraf Park,Catalonia, SpainIsabel Soria García191 towards ecological management191 Reflections on the management <strong>of</strong> monastic lands and facilitiesJosep-Maria Mallarach and Thymio Papayannis201 Part Three: Achieving synergy between spiritual and conservation concerns203 <strong>IUCN</strong>-UNESCO Guidelines for protected area managerson <strong>Sacred</strong> Natural Sites: rationale, process and consultationRobert Wild225 <strong>Sacred</strong> natural sites in developed countriesThymio Papayannis235 Some thoughts on sacred sites, faith communities and indigenous peoplesGonzalo Oviedo241 Environmental action by the Ecumenical Patriarchate<strong>The</strong>odota Nantsou249 <strong>The</strong> Ouranoupolis Statementon sacred natural sites in technologically developed countries255 Appendices

Opening messageHAH <strong>The</strong> Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I

Opening statementsDimitrios TziritisFather GregoriosWelcome speech,Dimitrios TziritisDear participants,On behalf <strong>of</strong> the Prefect <strong>of</strong> Halkidiki, thePrefectural Board and the people <strong>of</strong>Halkidiki, it is my pleasure to welcomeyou all to Halkidiki. I would also like tosay that we are delighted to see the 2 ndDelos Initiative Workshop being organisedin Halkidiki.After years <strong>of</strong> unsustainable practices,the Greeks have realised the most selfevidenttruth: that nature is our society’smain resource base and that our futurewell-being depends on the harmoniousrelationship between nature and humans.We really need to look back, learnfrom past lessons and realise how verydependent we are on nature. We have todo that if we are to enhance our quality<strong>of</strong> life now and build more sustainablecommunities for the future.Now is the time to act and introduce environmentalmitigation —wherever thatis possible— and preservation measuresand techniques whose ultimategoal, <strong>of</strong> course, is our current and futuresustainability.As the Vice-Prefect responsible for EnvironmentalIssues, I understand that oursociety has continuously and robustlydemanded that its decision —and policy-makers—establish new and attainabletargets, introduce new initiatives andboost its efforts to achieve the goals thatwe have collectively set.< <strong>The</strong> Tower <strong>of</strong> Ouranoupolis, Halkidiki, Greece

Nevertheless, there are several stagesin the struggle for environmental sustainability,which requires careful planning,informed decisions and dynamicimplementation. Several areas <strong>of</strong> concernhave distinct characteristics <strong>of</strong> theirown, which give rise to specific and diverseproblems that should be managedaccordingly.Mount Athos, the world’s oldest monasticstate, a unique site <strong>of</strong> historic, environmentaland cultural importance, theexceptional and dominant ‘Garden <strong>of</strong>the Virgin Mary’, is located on theHalkidiki peninsula. <strong>The</strong> conservationand management <strong>of</strong> Mount Athos’ naturaland cultural heritage requires theconsideration <strong>of</strong> several topics, reflectionon many important issues, contemplation<strong>of</strong> distinct aspects <strong>of</strong> sustainabilityand, ultimately, careful management.In the days ahead, we will have the opportunityto progress on many vital issuesregarding the conservation <strong>of</strong> thenatural environment. Your ideas, reviewsand criteria are important, and thismakes the Delos Initiative a scheme <strong>of</strong>particular importance; we are glad, asthe Prefecture <strong>of</strong> Halkidiki, to be activelyparticipating in this initiative.I would like to thank you again for hostingthe event in Halkidiki and to wish youall the best. I look forward to seeing theresults <strong>of</strong> your efforts.Iviron Monastery, Mt Athos10

IntroductionThymio Papayannis and Josep-Maria Mallarach<strong>Sacred</strong> natural sites and theDelos InitiativeAs environmental problems continue toincrease at an ever more rapid rate, exacerbatedby the major threat <strong>of</strong> global climatechange, the need for widespreadremedial action is becoming ever morepressing. Scientific consensus on boththe root causes <strong>of</strong> these problems andthe measures required to tackle them isgrowing, while mass media and public interesthas reached fever pitch. Of course,while this has put pressure on decisionmakersto take positive action, the realisation<strong>of</strong> the gravity and extent <strong>of</strong> the environmentalproblems has encouraged allthose concerned about the state <strong>of</strong> ourworld to search for partners around it: onesuch significant partnership to emerge inrecent years is between those concernedwith the conservation <strong>of</strong> nature –and <strong>of</strong> itsbiodiversity– and the custodians <strong>of</strong> sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites, representing both indigenousbeliefs and mainstream faiths.Natural sites are defined as those that maintaina significant degree <strong>of</strong> biodiversity andtherefore merit protection status, whetherlocal, national or international. Such sitesare usually part <strong>of</strong> protected areas and benefitfrom active management <strong>of</strong> some kind;although this can be applied through a widerange <strong>of</strong> means, in technologically developedcountries such management tendsto be in the hands <strong>of</strong> special managementbodies –whether governmental servicesor NGOs– or even local communities . As is <strong>of</strong>ten the case in Community Conserved<strong>Areas</strong> (CCAs).< Ouranoupolis, Halkidiki, Greece13

However, the existence <strong>of</strong> protected areasis probably as old as the history <strong>of</strong> humanity.In many parts <strong>of</strong> the world, naturalsites have acquired spiritual significancethrough the ages for indigenouspeoples, local communities or particularmainstream faiths and groups <strong>of</strong> believers.In addition, some sites which weresacred to now defunct societies, whilestill meriting a degree <strong>of</strong> respect, havemaintained only their historical and culturalvalue.As a result, most technologically developedcountries have a multitude <strong>of</strong> diverseand complex natural sacred sites,which connect ancient and modern spiritualtraditions through history: sacredlandscapes relating to prehistoric cultureswith tangible traces, like rock paintingsor labyrinths, or without them; sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites related to ‘dead’ historic culturesfrom megalithic civilisations onwards,some <strong>of</strong> which have been revivingin recent times in certain regions orare well-documented by traditional literarysources like epics or sagas; sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites relating to living indigenous spiritualtraditions; sacred sites and pilgrimageroutes related to long-established livingmainstream religions; and new sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites related to either recently-establishedmainstream religions or mainstreamreligions recently established in anew geographical location: e.g. Buddhismin Europe.Characteristic examples <strong>of</strong> natural sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites related to prehistoric culturesinclude Stonehenge in England, Carnacin France and the megalithic structureson the islands <strong>of</strong> Malta and Minorca. Sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites related to indigenous livingtraditions are markedly present acrossNorth America (First Nations), Australia(Aborigines), New Zealand (Maoris), Russia,northern Scandinavia (Sami) and afew other European countries like Estonia.<strong>Sacred</strong> sites related to ancient historicreligions occur frequently in the MediterraneanBasin, with examples includingDelos, Delphi and the Parthenon on theAthens Acropolis . <strong>Sacred</strong> natural sitesrelated to Christianity are still frequent inmost countries where the Orthodox and /or Catholic faiths are or have been theprinciple religions, and usually relate toplaces where holy people lived or weretouched by celestial beings. <strong>The</strong>re are alsoa number <strong>of</strong> related examples <strong>of</strong> livingpilgrimages, including the Camino deSantiago de Compostela (Way <strong>of</strong> StJames) in northern Spain, France andPortugal; the Via Laurentana in Italy; ElRocßo in Spain and Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in the Rhône Delta, France.<strong>The</strong> sanctity <strong>of</strong> a site is usually related tothe integrity <strong>of</strong> its natural features, whichis to say that it is normally compatiblewith the requirements <strong>of</strong> nature conservation.In fact, many countries firstsought to establish natural protected areasbecause <strong>of</strong> sacred sites or pilgrimagepaths. For instance, the largest concentration<strong>of</strong> Biosphere Reserves in Europeis related to the Camino de Santiagoin Northern Spain. However, this canlead to conflict stemming either from thepressure put on the natural environmentby large numbers <strong>of</strong> pilgrims and / or visitors,or from protected area managersaffording insufficient recognition to spiritualor religious values and their require- Dedicated to the goddess Athena.14

<strong>The</strong> participants at the Delos2 Workshopments. In old sacred sites located withinmodern protected areas, the lack <strong>of</strong> acommon language shared by custodiansand managers has proven to be anobstacle to co-operation.Preventing and resolving such conflictsis one <strong>of</strong> the missions <strong>of</strong> the Delos Initiative,which attempts to encourage synergythrough collaboration between custodians<strong>of</strong> sacred sites and managers <strong>of</strong>protected areas. Established in 2004within the framework <strong>of</strong> the Cultural andSpiritual Values <strong>of</strong> <strong>Protected</strong> <strong>Areas</strong>(CSVPA) Specialist Group <strong>of</strong> the InternationalUnion for Conservation <strong>of</strong> Nature(<strong>IUCN</strong>), the Delos Initiative focuses onsacred natural sites in technologicallydeveloped countries. As such, it concernsitself with sites that are significantfor indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada,the United States and elsewhere,as well as sites recognised by mainstreamfaiths including Buddhism, Christianity,Islam and Judaism.<strong>The</strong> Delos Initiative was named after theAegean island <strong>of</strong> Delos, a spiritual centre<strong>of</strong> the ancient Greek world. Jointly coordinatedby Thymio Papayannis andJosep-Maria Mallarach and supportedby Med-INA and Silene, its core methodologyis the study and analysis <strong>of</strong> carefullyselected case studies from aroundthe world from which experience can begained and lessons learned. Its firstWorkshop was organised in October2006 at the Monastery <strong>of</strong> Montserrat,which is located within a nature reservein Catalonia, Spain. <strong>The</strong> Workshop’s proceedingswere published in 2007. Ouranoupolis WorkshopIn October 2007, the 2 nd Delos InitiativeWorkshop was held in Ouranoupolis , alocation chosen for its proximity to Mt.Athos, Eastern Orthodox Christianity’s Mallarach, J.-M. and Papayannis, T. (<strong>eds</strong>.) (2007),<strong>Protected</strong> <strong>Areas</strong> and Spirituality, Proceedings <strong>of</strong>the First Workshop <strong>of</strong> the Delos Initiative, Montserrat2006, Gland, Switzerland: <strong>IUCN</strong> and Publicacionsde l’ Abadia de Montserrat. Held at the Eagles Palace Hotel, on 24-27 October2007.15

most celebrated monastic centre for overa thousand years. Ouranoupolis is asmall town in the North <strong>of</strong> the Athos Peninsulabut outside the borders <strong>of</strong> theHoly Mountain territory, to which womenare not permitted entry.<strong>The</strong> 22 participants at the Workshop includedreligious leaders, academics andconservationists from 11 countries andfour continents (see Appendix 1).<strong>The</strong> Workshop was divided into threeparts: <strong>The</strong> first concerned the presentationand critical discussion <strong>of</strong> new casestudies relating to both the spiritual traditions<strong>of</strong> indigenous peoples and to mainstreamfaiths which were not presentedat the first Delos Workshop. <strong>The</strong> secondtheme focused on the management <strong>of</strong>monastic lands, with examples drawnmainly from the Northern Mediterranean.Finally, the last day <strong>of</strong> the Workshop wasdedicated to examining and discussinggeneral issues relating to the provision <strong>of</strong>guidance to sacred natural sites, and tothe future orientation and planning <strong>of</strong> Delosactivities.<strong>The</strong> main results <strong>of</strong> the presentationsand discussions were summarised in theOuranoupolis Statement (p 249), whichwas subsequently translated into the<strong>IUCN</strong>’s other <strong>of</strong>ficial languages and widelydisseminated through the appropriatenetworks and the Delos Initiative webpageat http://www.med-ina.org/delos.Workshop participants then visited monasteriesin Meteora, <strong>The</strong>ssaly, theOrmylia Monastery in Halkidiki, the Verginaarchaeological site and the ByzantineMuseum <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong>ssaloniki.<strong>The</strong> Delos2 Workshopproceedings<strong>The</strong> proceedings are organised in thesame way as the Workshop.<strong>The</strong>y start with the blessing <strong>of</strong> His AllHoliness the Ecumenical Patriarch andopening statements made by the representatives<strong>of</strong> the Holy Community <strong>of</strong> Mt.Athos and the Prefecture <strong>of</strong> Halkidiki.<strong>The</strong>se are followed by three distinct sectionsdealing with i) the presentations <strong>of</strong>the new case studies, ii) the management<strong>of</strong> monastic lands, and iii) generalissues and the future orientation <strong>of</strong> Delosactivities.Part One:An overview <strong>of</strong> the case studiesIndigenous sacred sitesFollowing the introduction and openingspeeches, Part One <strong>of</strong> the Workshopproceedings includes two case studiesrelating to indigenous peoples in Australiaand the United States <strong>of</strong> America respectively,and four case studies relatingto mainstream faiths (Buddhism, Christianityand Islam) in Italy, Morocco, theRussian Federation and South Korea.<strong>The</strong> Dhimurru Indigenous <strong>Protected</strong> Areais located in Northeast Arnhem Land,Australia, and is comprised <strong>of</strong> severalsmaller sites. Yolngu, the Aboriginalpeople that inhabit the area, have a culturalobligation to manage their landswith respect to their ancestral traditions,applying effective conservation techniquesthat have in all likelihood ensuredtheir existence for more than 50,000years. <strong>The</strong> highly complex practices are16

Meteora, Greecehanded down from one generation tothe next through cultural transmission.Dhimurru is an example <strong>of</strong> a protected,sacred natural area for which indigenouspeople have sole management responsibility.<strong>The</strong>y have chosen to educatethe public through paintings, storiesand songs.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> San Francisco Peaks havebeen held sacred and accessed for specificreligious purposes for many centuriesby 22 Native American Nations.Commonly known as Dooko’oo’sliid,these peaks are recognised by the Navajopeople as a female life form, asource <strong>of</strong> medicinal and ceremonialplants and minerals, and a place <strong>of</strong> spiritualnourishment. High precipitation,several altitudinal vegetation zones, itsvarying directional orientation and a myriad<strong>of</strong> microhabitats make the mountainrange a haven <strong>of</strong> biodiversity. <strong>The</strong> mostserious threat to the natural and spiritual/ cultural values <strong>of</strong> the Peaks is posedby plans to build a ski resort on its southernslopes, which include the use <strong>of</strong>wastewater for effluent snow. In an effortto save the <strong>Sacred</strong> Peaks from pr<strong>of</strong>anation,13 tribes have formed the Save thePeaks Coalition to fight unwanted developmentprojects in the courts.Sites sacred to mainstream faiths<strong>The</strong> National Park <strong>of</strong> the Casentine Forests,Mount Falterona and Campigna,extends along the ridge <strong>of</strong> the Tuscan-Romagna Appenine in Italy. <strong>The</strong> CasentineForests are part <strong>of</strong> a National Parkthat covers around 36,000 ha. <strong>The</strong> Parkhosts a large number <strong>of</strong> plants and herbaceousspecies and is also rich in fauna,both mammals and birds. <strong>The</strong> area’smain sacred sites are the BenedictineHermitage and Monastery <strong>of</strong> Camaldoli,and the Franciscan Sanctuary <strong>of</strong> La Verna.People have lived and worked in thislandscape for many centuries, and ruinsand abandoned villages are still frequentwithin the park. Tourism has become animportant source <strong>of</strong> revenue for the area,but has also had a major impact both onthe forest and on the religious values <strong>of</strong>17

the park. Marked benefits would thus accrueto forming and supporting an integratedapproach for the entire area,which would protect the region’s natural,cultural and spiritual heritage withoutcompromising the future <strong>of</strong> its touristindustry.Jabal La‘l âm[Mount <strong>of</strong> the Signal] is situatedat the heart <strong>of</strong> the Jabal Bouhachemregion in the Rif mountains <strong>of</strong>Morocco. <strong>The</strong> spiritual importance <strong>of</strong> thesite derives from the presence at its peak<strong>of</strong> the famous tomb / sanctuary <strong>of</strong> ‘Abdal-Salâm ibn Mashîsh, a holy man whowithdrew there eight centuries ago. Nationalforest legislation and the existence<strong>of</strong> a ‘hurn’ —an Islamic traditional protectedarea— guarantee to a certain degreethe conservation <strong>of</strong> the natural heritage.<strong>The</strong> oak forests as well as the numerousspecies <strong>of</strong> mammals and birds,quite a few <strong>of</strong> them endemic or endangered,attest to the site’s biological andecological significance. Degradationcaused by the vast number <strong>of</strong> pilgrimswho visit the open-air sanctuary to prayis apparent. Some environmental damageis also a result <strong>of</strong> the traditional marketsthat operate in the locality.Mount Mani-san on the island <strong>of</strong> Ganghwa-donear the capital <strong>of</strong> South Koreais considered one <strong>of</strong> that country’s mostsacred mountains due both to its beautifullandscapes and magnificent views <strong>of</strong>the sea and –still more significantly– tothe fact that Dangun (the legendaryfounder <strong>of</strong> the Korean nation) allegedlyconstructed a stone altar on Mani-san’sChamseongdan peak over 4,000 yearsago and performed the first celestial <strong>of</strong>fering.While Mount Mani-san has aunique ecosystem –it is the home <strong>of</strong>many migratory birds, well preserved forest,etc.– its tideland is in great danger.<strong>The</strong> most serious conservation threatsare posed by the large number <strong>of</strong> visitorsand by several development projectsplanned for the region. <strong>The</strong> local governmenthas announced several ambitiousplans to reclaim the tideland, to build athermal power plant and to transform thearea into a tourist resort.Orchards in Vatopedi Monastery, Holy Mountain18

<strong>The</strong> Solovetsky Islands lie in the middle<strong>of</strong> the White Sea, 165 km South <strong>of</strong> theArctic Circle in Northern Russia. <strong>The</strong>unique archipelago in the European Part<strong>of</strong> the Arctic Ocean is comprised <strong>of</strong> overone hundred islands. <strong>The</strong> Solovetsky archipelagocontains sub-tundra and forest-tundraecosystems, crooked forests,numerous endemic species and a complex<strong>of</strong> small lakes. Many different cultureshave regarded the Solovetsky Islandsas sacred down the ages, whilesome <strong>of</strong> the islands number among OrthodoxRussia’s most sacred places.<strong>The</strong> monasteries, which were restoredafter the Communist era, and the increasingnumber <strong>of</strong> pilgrims who visit theislands every year, are gradually becominga significant factor in the life <strong>of</strong> the localcommunity.Part Two:Management <strong>of</strong> monastic landsand facilitiesPart Two includes case studies relatingto Mount Athos and other monasticcommunities in Rila (Bulgaria), Catalonia(Spain), Crete (Greece) and theSouthern Carpathians (Romania).At the end, a short paper attempts todraw conclusions and lessons fromthese presentations.<strong>The</strong> Athos Peninsula is the Easternmost<strong>of</strong> the three peninsulas in Halkidiki,Greece; it is roughly 60 km long. <strong>The</strong> HolyMountain is inhabited by a society <strong>of</strong>Monks who have devoted their lives tothe worship <strong>of</strong> God and is a sacred site<strong>of</strong> global significance. It is a Natural andCultural World Heritage Site and part <strong>of</strong>Europe’s Natura2000 network. <strong>The</strong> HolyCommunity <strong>of</strong> Mount Athos has successfullyimplemented a LIFE project relatingto the rehabilitation <strong>of</strong> coppiceQuercus frainetto and Quercus ilex tohigh forest, and has conducted a strategicSpecial Environmental Study to identifyand list the management measuresrequired to protect and restore the entirepeninsula with all its biotic and abioticconstituents, while promoting a developmentmodel compatible with the environmentaland economic concerns <strong>of</strong> thelocal community. Athos’ mountain landscapefeatures diverse vegetation and acomplex and pr<strong>of</strong>oundly beautiful topography,which has been preserved byan orthodox Monastic Community forover a millennium. <strong>The</strong> monastic lifestyle is characterised by temperance, silence,the careful use <strong>of</strong> natural resourcesand a concern for conservation. <strong>The</strong>need for special landscape conservationactions emerged after the wildfire <strong>of</strong>1990 and the road network that hassince been developed.Buila V ânturarit,ais a small Romaniannational park in the Southern Carpathians.<strong>The</strong> Park has three levels <strong>of</strong> vegetation–the deciduous, the boreal andthe sub-alpine– and boasts flora includingmany endangered, rare and endemicspecies. Carpathian fauna is also wellrepresented. <strong>The</strong> area is also known asthe ‘mountain <strong>of</strong> the monks’, and thereare six Orthodox monasteries and sketeswithin the Park, its only permanent humansettlements. <strong>The</strong> monasteries, situatedat the start <strong>of</strong> the tourist trails, forma circle around the National Park andare considered its spiritual guardians.<strong>The</strong> cultural values <strong>of</strong> the area are19

strongly related to the presence <strong>of</strong> theseChristian Orthodox monasteries <strong>of</strong> whichthe Bistrita Convent, built by the Craiovestiboyars, is the most famous. Librariesand museums dating back to the15 th century can also be found there.<strong>The</strong> main economic activities are woodharvesting and stock raising. An integratedapproach is, perhaps, the mosteffective strategy for preserving the naturaland cultural character <strong>of</strong> the areaand maintaining strong spiritual links betweenMan and Nature.<strong>The</strong> Monastery <strong>of</strong> Chrysopigi in Chania,Crete is dedicated to the Mother <strong>of</strong> God,the Life-Giving Spring. Since the 16 thcentury, it has been a source <strong>of</strong> spiritualand social support for the people <strong>of</strong> theisland. <strong>The</strong> land around the Monasteryis currently given over to cultivation usingorganic farming methods. <strong>The</strong> monastery’sestate has been designated aprotected area and is home to a variety<strong>of</strong> plants and trees, some <strong>of</strong> which areused in pharmaceutics. Apart from itsenvironmental significance, the archaeologicaland historical value <strong>of</strong> this biotopeare substantial. Further plans forthe conservation <strong>of</strong> the area should focuson both its natural and spiritualheritage.<strong>The</strong> Cistercian Monastery <strong>of</strong> Santa Mariade Poblet is located in Southern Catalonia.It was well known throughout WesternEurope during the 13 th -15 th centuriesfor promoting advanced sustainable techniquesin agriculture, forestry and animalhusbandry. <strong>The</strong> monastery was severelydamaged and its forest razed to theground during the social turbulence <strong>of</strong>the 19 th century, but the monastery andits surrounding forest were restored duringthe 20 th century. More than 150,000people visit Poblet Monastery every year,the majority <strong>of</strong> whom are attracted by itscultural heritage. <strong>The</strong> main natural significance<strong>of</strong> the Park is linked to the surroundingMediterranean forests. In 1984,the area around the Monastery was declareda Natural Site <strong>of</strong> National Importance.<strong>The</strong> monastic community has undertakenseveral initiatives which aim:i) to improve the environmental management<strong>of</strong> all the Monastery’s facilities andlands, ii) to promote the effective protection<strong>of</strong> the rural landscape around theMonastery and iii) to develop a strategyfor raising its visitors’ environmental andspiritual awareness.Rila Monastery was founded by SaintIvan Rilsky in the early 10 th century. Rila,which lies in the heart <strong>of</strong> a magnificentmountain massif, is Bulgaria’s holiestsite. Several other sacred placesare located around the Monastery, includingholy springs, the sacred cave<strong>of</strong> the founder and five hermitages. <strong>The</strong>Natural Park, which nestles within alarger national park, is home to a variety<strong>of</strong> distinct ecosystems and spectacularmountain landscapes, lakes, oldforests, and a number <strong>of</strong> endemicplants. <strong>The</strong> local fauna is extremely diverseand includes significant wolf andbrown bear populations. <strong>The</strong> maingoals <strong>of</strong> the 2003 management plan includeconserving the area’s spiritual,cultural and natural heritage; managingnatural resources in relation to tourism;raising awareness through educationalschemes and co-ordinating the activities<strong>of</strong> the Orthodox Church and state20

institutions. <strong>The</strong>se goals, which underlinethe strong relationship between themonastic community and the naturalenvironment, seek both to sustain themultifaceted role <strong>of</strong> the nation’s mostimportant cultural and spiritual centre,and to preserve the unity between themonastery and nature.Sakya Tashi Ling is a modern Buddhistmonastery located in El Garraf Park nearBarcelona in Catalonia, Spain. <strong>The</strong> property<strong>of</strong> the Sakya Tashi Ling Monastery is<strong>of</strong> significant natural, cultural and spiritualvalue. <strong>The</strong> monastic community’s repeatedlyexpressions <strong>of</strong> interest in improvingthe management <strong>of</strong> the naturalarea surrounding the Sakya Tashi LingMonastery have resulted in the drafting<strong>of</strong> a management plan, which seeks tointegrate the scientific conservationistand traditional Tibetan Buddhist worldviews.<strong>The</strong> Buddhist monastery is currentlythe Park’s main attraction, with visitorsattracted by the activities and courses<strong>of</strong>fered by the monastic communityand by the cultural significance <strong>of</strong> thePalau Novella building, in which the communitylives.Part Three: Achieving synergybetween spiritual and conservationconcernsPart Three begins with a summary <strong>of</strong> theefforts made to provide guidance to themanagers, custodians and administrators<strong>of</strong> sacred natural sites. <strong>The</strong> specificities<strong>of</strong> sacred natural sites in developedcountries are explored in a second paper,which is followed by ‘Some thoughtson sacred sites, faith communities andindigenous peoples’ and concludes witha presentation <strong>of</strong> the ecological activities<strong>of</strong> the Ecumenical Patriarchate across alarge part <strong>of</strong> the globe.Working under the auspices <strong>of</strong> the <strong>IUCN</strong>World Commission for <strong>Protected</strong> <strong>Areas</strong>(WCPA), the <strong>IUCN</strong> Cultural and SpiritualValues <strong>of</strong> <strong>Protected</strong> <strong>Areas</strong> SpecialistGroup has prepared a set <strong>of</strong> Guidelinesfor <strong>Protected</strong> Area Management on <strong>Sacred</strong>Natural Sites. <strong>The</strong> guidelines emergedout <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> meetings organis<strong>eds</strong>ince 1998 by UNESCO andthe <strong>IUCN</strong> in India, Mexico, China, SouthAfrica, Japan, the United Kingdom and–now– Greece. <strong>The</strong> drafting processbegan in 2003, and a preliminary set <strong>of</strong>working guidelines was posted on the Internetin 2005 and subsequently publishedby UNESCO. Although the guidelinesfocus on sacred sites relating to indigenouspeoples, they are just onemanifestation <strong>of</strong> the greater recognitionbeing afforded to historical and contemporaryconservation efforts rooted in anappreciation <strong>of</strong> the natural world initiatedby numerous communities across theglobe. <strong>The</strong> Guidelines were launched inBarcelona at the <strong>IUCN</strong> World ConservationCongress in 2008 .<strong>The</strong> next paper examines the specificities<strong>of</strong> sacred natural sites in technologicallydeveloped countries. <strong>The</strong> specificcharacteristics <strong>of</strong> these sites are significantfor both mainstream religions andindigenous peoples, and as such theirmanagement and conservation are examinedwithin the context <strong>of</strong> broader globalsocio-economic and spiritual trends. Wild, R. and McLeod, C. (<strong>eds</strong>.) (2008) <strong>Sacred</strong>Natural Sites: Guidelines for protected AreaManagers. Gland, Switzerland, <strong>IUCN</strong>.21

Several general recommendations areput forward, which are relevant to both.<strong>The</strong> complex issue <strong>of</strong> indigenous andtraditional peoples and communities indeveloping countries is addressed bythe paper Some thoughts on sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites, faith communities and indigenouspeoples. Through many years <strong>of</strong> <strong>IUCN</strong>work around the world, it has becomeobvious that indigenous faiths suffersubstantially less in developed than indeveloping nations, where the traditionalpeoples and cultures are more numerous,the areas involved much larger andthe scale <strong>of</strong> the problems consequentlymuch larger. As a result, the prospectsfor traditional spirituality are anything butbright. In addition, there are frequentconflicts between indigenous groupsand institutionalised religions that resultin the harassment and persecution <strong>of</strong>the former, which can jeopardise thevery survival <strong>of</strong> traditional cultures. Moreover,the critical issue <strong>of</strong> indigenouspeoples having lost their rights <strong>of</strong> tenureand <strong>of</strong> managing indigenous sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites remains unsolved in the majority <strong>of</strong>developing countries. Since all landswithin protected areas in Latin America,Asia and Africa are state lands, the rights<strong>of</strong> indigenous and traditional peoples totheir sacred sites cannot be restored.<strong>The</strong> ongoing degradation <strong>of</strong> traditionalinstitutions in developing countries,which began during the colonial era isanother major problem, exacerbated bya refusal to recognise indigenous spiritualityas legitimate. It is thus absolutelycrucial that mainstream religious institutionsbecome more open, ecumenicaland tolerant and abandon their colonialattitudes towards indigenous spirituality,which include their continued efforts toconvert indigenous people to institutionalisedreligions.In recent years, numerous environmentalorganisations have turned to religions insearch <strong>of</strong> allies in their nature conservationand environmental action. Environmentalaction by the ‘green’ EcumenicalPatriarch has been particularly notedand appreciated. <strong>The</strong> Ecumenical Patri-<strong>The</strong> Delos2 Workshop22

Part OneAnalysis <strong>of</strong> case studies- Indigenous peoples- Mainstream faiths25

Indigenous peoplesPower on this land; managing sacred sitesat Dhimurru Indigenous <strong>Protected</strong> AreaNortheast Arnhem Land, AustraliaBas VerschuurenMawalan II MarikaPhil WiseIntroductionThis case study outlines Dhimurru’s experiencewith the management <strong>of</strong> their sacrednatural sites which, in this article, willbe referred to as sacred sites. It begins witha general introduction and then proce<strong>eds</strong>to explain in greater detail Dhimurru’s experiencewith managing sacred sites usingthe two examples <strong>of</strong> Nhulun and Muruwirri.Nhulun provides a good example<strong>of</strong> fostering cross-cultural learning andsignifies the importance <strong>of</strong> sacred sites tothe land rights movement. Muruwirri highlightslessons learned from sacred art andmodern science-based exercises for mappingthe coastal and marine environmentwhich is also termed the ‘sea country’.Like all aboriginal cultures, Yolngu aboriginalculture is rich in spiritual values.Just as the Yolngu make no distinctionbetween ‘land’ and ‘sea’, there is no separationbetween these values and theenvironment. Hence their use <strong>of</strong> the termsea county for the coastal habitats <strong>of</strong>their clan estates, and their referring tothemselves as saltwater people (Memmot2004, Verschuuren 2006, Yunupingu2007). This unique integrated approachto cultural and natural values is betterunderstood when cultivating a deeperunderstanding <strong>of</strong> the tangible and intangibleimportance <strong>of</strong> Yolngu values.<strong>The</strong> cultural connection with the land is asacred one encompassed by the relationshipsbetween Rom (law / protocol),Manikay (song / ceremony) and Miny’tji(art) (see glossary). This may be easierto understand in the light <strong>of</strong> Graham’s in-< Sign at Yalangbara, Northeast Arnhem Land, Australia27

sights into the philosophical underpinnings<strong>of</strong> Aboriginal worldviews (2008):“<strong>The</strong> land, and how we treat it, is what determinesour human-ness. Because land issacred and must be looked after, the relationbetween people and land becomes thetemplate for society and social relations.<strong>The</strong>refore all meaning comes from land.”Learning from Dhimurru’s experienceswith managing sacred sites entails familiarisingoneself with the endogenous approachDhimurru has taken. It involvesmaking an effort to understand managementfrom within a culture. Based onthis, Dhimurru has developed the BothWays approach which will be detailedfurther throughout this article, as we illustratehow cultural and spiritual significancehelp guide management actionsfor the conservation and protection <strong>of</strong>sacred sites.Map <strong>of</strong> the Intigenous <strong>Protected</strong> Area with sacred sites marked28

Location<strong>The</strong> Dhimurru Indigenous <strong>Protected</strong> Area(IPA) is located in Northeast ArnhemLand Australia. Located on Aboriginalland, the Dhimurru IPA surrounds Nhulunbuy,the Northern Territory’s fourthlargest city. It is named after the sacredhill <strong>of</strong> Nhulun at whose base the miningtown is built. <strong>The</strong> IPA also includes Dhambaliya(Bremer Island) <strong>of</strong>f the shore to theNorth <strong>of</strong> Nhulunbuy. <strong>The</strong> IPA covers a totalterrestrial area <strong>of</strong> c.92,000 ha with anadditional 9,000 ha <strong>of</strong> coastal watersbounded by Nanydjaka (Cape Arnhem),Yalangbara (Port Bradshaw), Djuwalpawuy(Mount Dundas) and Dhambaliya(Smyth 2007). To the North and East, theDhimurru IPA is bordered by the sea; tothe South, its sea estate and lands arebordered by Laynhapuy IPA and managedby the Yirralka rangers at LaynhapuyHomelands who, like Dhimurru,have united the management <strong>of</strong> theirHomelands.<strong>The</strong> sites referred to throughout this articlehave been indicated on the map (inp. 28). <strong>The</strong>y cover both land and sea andare populated in varying densities. <strong>The</strong>sesites are known to Yolngu as: Nhulun(Mount Saunders) and Muruwirri andDhambaliya Channel (Lonely Rock andBremmer Channel).Dhimurru, the organisationYolngu cosmology is divided into twomoieties called Yirritja and Dhuwa. LikeYing and Yang, Yirritja and Dhuwa includepeople, plants, animals and land. Yirritjaand Dhuwa are part <strong>of</strong> Dhimurru throughthe collaboration <strong>of</strong> Yirritja and Dhuwaclans. Dhimurru itself was founded in 1992and is governed by the Dhimurru ExecutiveBoard, which consists <strong>of</strong> 20 representatives—mostly Traditional Owners(see glossary)— from the traditional clanestates that comprise the Dhimurru IPA(<strong>of</strong>ficially declared in 2000). <strong>The</strong> DhimurruExecutive board is advised by the DhimurruAdvisory Group, whilst the Dhimurrustaff implement the management planand related conservation projects.Natural and cultural heritage values withinthe Dhimurru IPA are managed fromwithin the cultural worldview <strong>of</strong> theYolngu people, and therefore strive to betreated inclusively. From this position,the Yolngu people have developed partnershipsand working relationships withvarious conservation, government andscientific institutes. Although the managementapproach to the land is alwaysbased on a Yolngu perspective, Dhimurrufosters different ways <strong>of</strong> understandingthe unique natural heritage in the IPA.To this end, a unique Both Ways managementapproach has been established.<strong>The</strong> Both Ways management approachstems from the need <strong>of</strong> Yolngupeople to seek greater recognition fortheir culture than that which could be assertedthrough a joint managementagreement <strong>of</strong> the sort initially proposedby the Australian Government. Dhimurruprovides an example <strong>of</strong> a protected areawhose management is entirely the responsibility<strong>of</strong> Indigenous people, whohave chosen to exercise that responsibilityby negotiating partnerships with governmentaland non-governmental organisations(NGOs) to produce an alterna-29

tive to joint management (Smyth 2007).<strong>The</strong> IPA is a voluntary managementagreement with the Australian government,which closely resembles Indigenousand Community Conserved <strong>Areas</strong>(ICCA) or the World Conservation Unions’(<strong>IUCN</strong>) Category V. <strong>The</strong> YolnguPlan <strong>of</strong> Management recognises Yolnguvalues, natural heritage values and othercommunity values (Dhimurru 2000).Natural valuesAs explained earlier, the meaning <strong>of</strong> naturalheritage is defined from a Yolngucultural perspective, in which culturaland biological values have been inextricablylinked since time immemorial (Posey1999, Hutcherson 1995, Dhimurru2006a). To Yolngu people, the reciprocity<strong>of</strong> these values is evident. Yolngu peoplehave always been concerned with educatingBalanda in this interconnectivity,as illustrated by a statement in Dhimurru’ssea country management plan:“We have always known that we havesome <strong>of</strong> the most culturally and ecologicallysignificant shores and sea countryin Australia. Finally, it seems the non-indigenousworld has caught up”.<strong>The</strong> Plan further describes Yolngu’s intimateknowledge <strong>of</strong> the sea from theirperspective as saltwater people:“Our marine estates include islands, rockyand coral reefs, inlets, bays, estuaries,mudflats, underwater springs, sea grassmeadows, mangrove forests, the sea bedand open ocean. We share our sea countrywith marine creatures including fish,whales, dolphins, crustaceans, corals,dugongs, turtles, shellfish, crocodiles andsea and water birds. We can describeand name in detail coastal, underwaterand <strong>of</strong>fshore features. We know and understandin detail the behaviour and habitat<strong>of</strong> marine life”. (Dhimurru 2006a)Yolngu have a rich culture with a pr<strong>of</strong>oundunderstanding <strong>of</strong> nature. <strong>The</strong>yhave been exposed to European valuessince 1935, when a Christian missionwas established at Yirrkala: the youngpeople <strong>of</strong> that time are the elders <strong>of</strong> today.Since then, they have seen modernscience explore their culture and the naturalenvironment <strong>of</strong> their clan estates. Afterearly explorers like Charles Darwinand Matthew Flinders mapped watersand coastline, various overland expeditionssurveyed the natural environment <strong>of</strong>Northeast Arnhem Land. <strong>The</strong> collections<strong>of</strong> such expeditions are on display in museumsaround Australia. One such collectionis the Donald Thompson Collectionat the Victoria Museum (Thomson1983) from the 1948 American-AustralianScientific Expedition to Arnhem Land.<strong>The</strong> Yolngu are interested in deepeningscientific understanding and integratingit into the day-to-day cultural management<strong>of</strong> their land and sea estates. Severalscientific studies have been undertakenin collaboration with Dhimurru.Both Dhimurru and the Northern TerritoryParks and Wildlife Service (PWNT) hassuccessfully applied the Both Ways approachin training Yolngu to assist in inventoryand monitoring programmescovering macropods, insects (notablythe endemic Gove butterfly), mammals,fish, reptiles and plants. However, theunique and pristine environment remains30

elatively unexplored by modern science.Two weeks <strong>of</strong> collecting insects generatedextensive material including the discovery<strong>of</strong> species previously unknown tomodern science. In addition, the YolnguPlan <strong>of</strong> Management (Dhimurru 2000)recognises specific natural heritage valueswhich, following Smyth (2007), include:high plant diversity and intact faunalassemblages; coastal regions notrepresented in any other protected area—the largest Quaternary dune systemon the Northern Territory mainland, forinstance; and significant feeding habitatsand nesting sites for seabirds, migratorybirds and threatened species <strong>of</strong>marine turtle and dugong (Smyth 2007).<strong>The</strong> marine turtle and the dugong are <strong>of</strong>particular cultural interest to Yolngu people.Seven species <strong>of</strong> turtle occur inDhimurru IPA, six <strong>of</strong> which are known tonest there: the Olive Ridley (LepidocheliysOlivaces), Hawksbill (Eretmochelysimbricate), Leatherback (Dermochelyscoriacea), Loggerhead (Caretta caretta),Flatback (Natator depressus) and Greenturtle (Chelonia mydas). Marine turtlesare in decline in most parts <strong>of</strong> the worldand are included in the <strong>IUCN</strong> Red List.Dhimurru has learned from other monitoringstudies how to put effective managementpractices in place to help decliningpopulations recover. Such managementpractices include protectinghabitat (through Dhimurru’s permit systemand patrols), advocating the use <strong>of</strong>Turtle Exclusion Devices in fisheries andensuring that the traditional harvest <strong>of</strong>eggs and turtles is sustainable (throughthe Sea Country Management Plan). <strong>The</strong>dugong (Dugong dugong: the sea cow)also occurs in the Dhimurru IPA, althoughnumbers are known to be keptlow by the limited availability <strong>of</strong> seagrass(Halophila ovalis and Haloduleuninervis) feeding grounds.Cultural and spiritual valuesSince Dhimurru is an Aborigine-ownedorganisation looking after aboriginalland, their management practices aresubsequently based on cultural values.To Dhimurru, therefore, the whole landscapeis regarded as culturally significant,with specific sacred places andspecies on it, which can be said to embodyspecial spiritual connections to theancestral beings that created the land ina period called ‘the Dreamtime’. Accordingto Rose (1998), the concept <strong>of</strong>Dreamtime is very real to Aboriginal peopleand <strong>of</strong>ten hard to understand forEnglish-speaking people, because thereis no adequate translation into English.<strong>The</strong> ancestor beings —Wangar— createdthe landscape and sang it —with therocks, lakes, trees, sea and animals alivewithin it— into being. This means thatAboriginal people are spiritually connectedto the landscape, but also to specificplants and animals. <strong>The</strong> Manikay songs<strong>of</strong> the ancestors are records <strong>of</strong> their travelsas they created the land, and theyhave been passed on from one generationto the next since time immemorial(Morphy 1991, Chaloupka 1993, Memmot2004). As the ancestors laid downthe law (Rom), the songs, stories(Dhawu), art (Miny’tji), dance and musicalinstruments form a unique and powerfulmedium through ceremony (whichoutsiders call corroboree) and guideYolngu life (Morphy 1998). This means <strong>of</strong>31

Newspaper clipping relating to the first protest ceremony in the 1960scommunicating cultural and spiritual valuesis widely recognised by society as ahighly influential and powerful mediumfor educating and influencing people.Yolngu people today still practice theirheritage in this traditional way, using it toenrich and strengthen their land and seamanagement practices. <strong>The</strong> followingsections will detail the cultural significanceto the Yolngu <strong>of</strong> the two sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites, and the role Dhimurru plays inmanaging them.A history <strong>of</strong> land rights atNhulun (Nhulun lookout)Nhulun is a natural hill and a sacred siteenclosed on three sides by the NhulunbuyTownship, which is home to over4000 residents. It was at the centre <strong>of</strong> thefirst legal claim made for Aboriginal traditionalownership <strong>of</strong> land and customarylaw, a legal action which ultimately resultedin the passing <strong>of</strong> the AboriginalLand Rights Act (ALRA, 1976). It canthus be said that the struggle for landrights began when this sacred site wasdamaged by road works (see image inp. 32). A protest ceremony (the GalthaBunggul) was held on the damaged site(Dhimurru 2007) prior to the Yolngu peoplecreating a statement <strong>of</strong> their ‘titlede<strong>eds</strong>’ glued onto a bark painting (commonlyknown as the Bark Petition) andpresenting it to the Australian House <strong>of</strong>Representatives in 1963. <strong>The</strong> Bark Petitionmade particular reference to the sacredness<strong>of</strong> the land:“...That the land in question had beenhunting and food gathering groundsfor the Yirrkala tribes from time immemorial.That places sacred to the Yirrkalapeople, as well as vital to theirlivelihood are in the excised land. Thatpeople feel that their ne<strong>eds</strong> and interestswill be completely ignored as theyhave been ignored in the past.” (fromHutcherson 1995).<strong>The</strong> Federal Court initially rejected theclaim, upheld the hypothesis <strong>of</strong> TerraNullius (meaning ‘empty land’, a Latin32

Re-enactment <strong>of</strong> the Galtha Bunggul in 2007dictum legally applied to claim a territoryunder public law) and did not recogniseYolngu law or the Yolngu people as Australiancitizens. However, the Royal Commissionadvised that the Nabalco miningcompany and the Commonwealth hadwrongfully entered Aboriginal land on thebasis <strong>of</strong> leases initially granted by theCommonwealth. This ruling resulted inthe ALRA, which has allowed approximately50% <strong>of</strong> Northern Territory land tobe handed back to Traditional Ownerssince 1976.Traditionally, Nhulun is a sacred site relatingto a ‘sugarbag’ dreaming, the maternalbirthplace <strong>of</strong> the wild honey orsugarbag produced by native bees andconsidered a delicacy among Yolngu.Nhulun is a registered sacred site underthe 1989 Northern Territory <strong>Sacred</strong> SitesAct (1989) as well as a recreational area.A sealed road provides access for motorvehicles to a steel watch tower (Nhulunlookout) overlooking the surroundinglands. <strong>The</strong> lookout has been providedwith signs explaining the cultural andspiritual values <strong>of</strong> the sacred site as wellas its importance to the land rights movement.<strong>The</strong> signs include a timeline coveringthese events chronologically from aYolngu perspective, and is a good example<strong>of</strong> Dhimurru’s strategy <strong>of</strong> promotingreconciliation and cultural understandingthrough the interpretation <strong>of</strong>Yolngu beliefs and values to visitors(Smyth 2007).Nhulun is <strong>of</strong> high cultural significance toYolngu people, who still carry out a ceremonyat Nhulun. <strong>The</strong> last ceremony tookplace on 1 May 2007 and was a commemorativere-enactment <strong>of</strong> the GalthaBunggul held in 1969 (see image in p.32). <strong>The</strong> re-enactment was timed to coincidewith the opening <strong>of</strong> the interpretivedisplay at Nhulun, which describes its importanceto Australian history and culture(see image in p. 33). <strong>The</strong> re-enactmentbrought together Yolngu as well as nonindigenouspeople including government<strong>of</strong>ficials and schoolchildren to celebrateYolngu culture and the recognition <strong>of</strong> landrights. However, despite this legal recog-33

nition <strong>of</strong> Yolngu land rights, the Yolngupeople continue to fight for the willingand cooperative recognition <strong>of</strong> theserights by non-indigenous people. This isreflected in the Dhimurru permit systemand in the restoration activities Dhimurruhas had to carry out as a result <strong>of</strong> the undesirableimpact <strong>of</strong> visitors.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> Paintings <strong>of</strong> Muruwirriand Dhambaliya (Lonely Rockand Bremmer Channel)<strong>The</strong> Dhambaliya Channel and Muruwirriare both good examples <strong>of</strong> sacred sitesin the marine environment commonlycalled the sea country by the Yolngu,who also refer to themselves as ‘SaltwaterPeople’ (National Oceans Office2004). Djawa Yunupingu, the director <strong>of</strong>Dhimurru explains the Yolngu connectionto the sea country when talkingabout the sea country management planDhimurru has been working towards:“For Yolngu, sea country is very importantculturally. When we sit, when wethink, when we sing and when we dream,we have visions about sea country.Yolngu sing about the winds coming infrom the ocean. <strong>The</strong> sacred sites fromthe Dreaming stories are there, too. Wesing some animals from the sea, whichare sacred to us, passed down from onegeneration to the next. Yolngu have sacr<strong>eds</strong>ites in sea country because storiesare tied up with that land underneath it.That’s why we paint and we explainthose drawings and paintings. It is not apainting; it is a map, a map <strong>of</strong> the Dreamingand sea creatures and sacred sites.<strong>The</strong>re are many stories behind it. Dhawu,or stories, are very important to Yolngu”.(Yunupingu and Muller 2007).<strong>The</strong> paintings <strong>of</strong> Muruwirri shown in thischapter illustrate how the site is interconnectedwith the broader seascape commonlyknown as the Dhambaliya (Bremmer)Channel.Muruwirri is a single rock protruding out<strong>of</strong> the sea in the Dhambaliya Channel.<strong>The</strong> Channel is sacred to the Riratjinguand Djambarrpuyngu clans, and in anarea influenced by the Djambawal, theThunderman and Daymirri, the ancestralwhale. This place, song and significanceextends to knowledge about featuresand landmarks that are at the bottom <strong>of</strong>the ocean floor but were dry land some10,000 years ago (Buku-larrngay MulkaCentre 1999). This sea country is alsoimportant culturally, because the storiesrelate to heritage dating back to theDreamtime and the testimony <strong>of</strong> famousturtle hunters. Turtle hunting is still regardedas a very important part <strong>of</strong> Yolnguculture. Although most <strong>of</strong> the pressureon turtle populations are due to the activities<strong>of</strong> Balanda (non-Aboriginal people),sacred places and cultural heritage canhelp conservation practices to generateYolngu acceptance <strong>of</strong> potential regulationssuch as hunting limits which renderthe harvest sustainable.<strong>The</strong> two paintings (images in p. 35) telldifferent stories, but the stories relate tothe same place: Dhambaliya Channeland Muruwirri. <strong>The</strong> Painting by MawalanII Marika shows Muruwirri at the bottomwith the white <strong>of</strong> the bird droppings on itstop. <strong>The</strong> two king browns also refer to thesacred digging sticks called Mawalan34

that point to a well <strong>of</strong> freshwater thatsprings from the ocean floor and is surroundedby patterns depicting the sacredcurrents <strong>of</strong> the sea. All these features existin the Dhambaliya Channel. As theyare painted through sacred design, theyrefer to stories that contain a rich source<strong>of</strong> information about the ecosystem. <strong>The</strong>painting by Mawalan Marika (Mawalan IIMarika’s grandfather) was designed toreveal some <strong>of</strong> these stories to two anthropologists(Ronald and CatherineBerndt) in the late 1940s. According toMawalan II Marika, the detailed informationdepicted in the painting (Muruwirribeing the yellow circle surrounded by animalsin the bottom left corner) by hisgrandfather is also present in his ownpainting, and those who are initiated inthe knowledge can see it. According toMawalan II Marika, “It is the easiest wayto explain what we know about what is inthe sea and what is in the land”. MawalanII Marika also comments on the Balandamap (meaning geographical maps): “It’sreally hard, I look at it and I can’t evenfind it [the place and the story]. <strong>The</strong>semaps don’t match”.Yolngu artwork has many levels <strong>of</strong> meaningthat are revealed to people in accordancewith their status, gender and level <strong>of</strong>Painting <strong>of</strong> sea country. Gunda MuruwirriPainting <strong>of</strong> sea country. Dhambaliya myth map35

initiation. <strong>The</strong>ir meaning ranges along acontinuum from ‘inside’ or secret (<strong>of</strong>tensacred) to ‘outside’ or public knowledge(Hutcherson 1995). <strong>The</strong> explanationsalong this continuum are also referred toas ‘open’ or ‘closed’ stories. <strong>The</strong>re is agrowing awareness <strong>of</strong> the importance <strong>of</strong>saltwater paintings since the 80 barkpaintings painted by Yolngu toured Australianmuseums in the course <strong>of</strong> gainingrecognition for indigenous sea rights in1997. <strong>The</strong> cultural information containedin such paintings is <strong>of</strong> paramount importancein the understanding <strong>of</strong> ecosystems,and even more important for successfulconservation practices. Anotherkey to understanding the importance <strong>of</strong>the Yolngu perception <strong>of</strong> nature to conservationis Yolngu’s intimate spiritual relationswith the sea country and the speciesin it. Throughout North-eastern ArnhemLand and the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Carpentaria,anthropologists have documented whatis called ‘calling up’ or ‘dreaming up’marine resources, or ‘talking to country’,which related to applying that spiritualrelationship to land, the sea and the speciesin it (Chaloupka 1993, Cordell 1995,Memmot 2004). Yolngu people assertthis relationship in their sea country managementplan thus:“We call up the names we have for importantplaces in our sea country for differentreasons and purposes —someare deep and secret” (Dhimurru 2006a).Pressures and impactsYolngu people have a cultural responsibilityto manage the land in accordancewith spiritual obligations owed to theirancestors. This way <strong>of</strong> managing theland has sustained Aboriginal peoples’presence on the land for what could beas long as 50,000 years (Chaloupka1993, Memmot 2004, Yunupingu 2007).Although some Aboriginal practices <strong>of</strong>land management such as fire managementmay seem detrimental to the unaccustomedeye, they are in fact highlycomplex practices that are widely creditedas being successful in managing,sustaining and enhancing ecosystem biodiversity.<strong>The</strong> continuity <strong>of</strong> caring forthe country handed over from one generationto the next is also part <strong>of</strong> a processcalled ‘cultural transmission’. Onefeature <strong>of</strong> attention with fire-managementis that the healthy ecosystem that resultsfrom it is directly related to cultural integrity.For example, if Aboriginal people donot have their traditional cultural firemanagementin place, the country receivesless attention, the intervals betweenfires become too long, and fireevents are inevitable too hot and prolonged,thereby having a negative impacton biodiversity and the area’s carbonsequestration capacity (Muller 2007).Maintaining traditional practices thus dependson keeping culture strong andcentral to the management <strong>of</strong> DhimurruIndigenous <strong>Protected</strong> Area.<strong>The</strong> Yolngu people have had to adapt tothe permanent residence <strong>of</strong> non-indigenousAustralians —referred to collectivelyas Balanda by the Yolngu people—since the mid 1930s. However, it wasthe impact <strong>of</strong> Balanda living at Nhulunbuysince the 1960s which promptedTraditional Owners to establish Dhimurruto better control and manage the in-36

creasing threat posed to the land. Tohalt unlawful access to land and potentialdamage to sacred sites, Dhimurrumanages an access permit system thatis at the forefront <strong>of</strong> the movement forgetting their rights recognised. Dhimurru’spermit system is an attempt at regulatingvisitor experience and impactwithin areas allocated for this purpose.<strong>The</strong> permit provides access to areasappointed by Traditional Owners as recreationalareas. Apart from regulatingthe impact <strong>of</strong>, for instance, four-wheeldrive access to beaches or campingand fishing, these recreational areashave been selected on the basis <strong>of</strong>Yolngu concern for visitor safety asmuch as safeguarding the sacred sitesoutside their perimeters.Not surprisingly, most <strong>of</strong> the pressureson the natural (and <strong>of</strong>ten, indirectly, cultural)values <strong>of</strong> the IPA originate elsewhere.Of course, some <strong>of</strong> the factorswhich impact on the environment are beyondDhimurru’s scope <strong>of</strong> management.Some <strong>of</strong> these pressures are <strong>of</strong> internationalsignificance and caused by globalprocesses such as climate change (e.g.greenhouse gas emissions), overfishing(e.g. bycatch and habitat destruction)and marine debris (e.g. ‘ghost nets’)washing up on stretches <strong>of</strong> coastlinewithin the Dhimurru IPA. Dhimurru aimsto address the forces behind those pressuresthrough its cooperation with otherinstitutions such as the CarpentariaGhost Nets Programme, the WorldwideFund for Nature (WWF) and the AustralianQuarantine Inspection Services(AQIS) and Customs. An example <strong>of</strong>such collaboration being put to gooduse is in the drive to address the declinein sea turtle and dugong populations(both <strong>IUCN</strong> Red-Listed species) due toboat strikes, overfishing, ghost net entrapmentand habitat destruction outsidethe Dhimurru IPA on a national and internationallevel. Other activities on the part<strong>of</strong> the residents <strong>of</strong> and visitors to Nhulunbuy—such as increasing numbers <strong>of</strong>tourists, the behaviour <strong>of</strong> recreationaland commercial fishermen and the activities<strong>of</strong> the Rio Tinto-Alcan mining company—impact directly on Dhimurru.Conservation perspectives andsustainabilityAs cultural and spiritual values are increasinglyintegrated into new conservationmanagement approaches, they becomean integral part <strong>of</strong> the benefits natureprovides to society. <strong>The</strong>se benefits(which include hunting, fishing and recreation)are termed ‘ecosystem services’and contribute to the socio-economicdevelopment <strong>of</strong> Dhimurru IPA and thewell-being <strong>of</strong> the Yolngu and Balandawho enjoy the cultural and natural richness<strong>of</strong> the area. A promising opportunityto integrate cultural and spiritual valuesinto management approaches wouldbe to establish historic baselines, whichdocument species density over timebased on cultural memory, song and artas well as other sources <strong>of</strong> cultural information.As relatively little scientific informationexists on species abundanceand behaviour, information <strong>of</strong> this sortderived from a cultural basis may be regardedas crucial to the defining <strong>of</strong> managementobjectives.37

From traditional culture tomodern scienceDhimurru manages two ends <strong>of</strong> thespectrum from traditional culture to modernscience. This entails that what tomap and what not to map should bebased on a cultural basis. From a scientificperspective, it may be argued thatmaps are commonplace and well-developedfor the terrestrial areas <strong>of</strong> theDhimurru IPA, but that no accurate mapsexist for its marine areas. From a culturalperspective, however, we have seen thatthis assumption is not entirely correct asdetailed maps do exist (see images in p.35). When negotiating the means bywhich mapping exercises are to be conducted,the assessment <strong>of</strong> a comprehensivesystem for storing these differentinformation types will have to be considered.It has been suggested that aGIS database be developed with layersfor each information source. <strong>The</strong>se layersand the information sources containedin them could then be passwordprotected.It would thus be possible todevelop points on a map linked to a videowith password protection. In suchcases, there is a need for a committee todecide on what is acceptable and whatis not in terms <strong>of</strong> mapping and data storage.This would also win cultural approvalfor the process and legitimacy for itstools and modus operandi.Dhimurru is uniquely placed to integratemanagement objectives into a culturalperspective. Coordinating the mappingexercise thus includes forming synergiesbetween the interests <strong>of</strong> the parties involvedand ensuring this is done in amanner respectful to cultural and spiritualvalues. <strong>The</strong> intended cooperationgoes beyond science working with culturalconservation projects: it is an opportunityto include and unite the qualities<strong>of</strong> Yolngu institutions such as theBuku-larrngay Mulka Centre, the NorthernLand Council and Dhimurru LandManagement Corporation itself. <strong>The</strong> contribution<strong>of</strong> spiritual values to the conservationefforts that could be supportedthrough the mapping process could alsoprovide a vehicle for developing potentialmeans <strong>of</strong> safeguarding the spiritualvalues <strong>of</strong> those sites through their inclusionin patrolling programs, data storagesystems and cultural databases kept atthe Buku-larrngay Mulka Centre.Mapping DhambaliyaSynergies between the conservation <strong>of</strong>natural heritage and the protection <strong>of</strong>spiritual and cultural values are beingdeveloped thought the mapping exercise.Both Yolngu traditional knowledgesystems and their perceptions <strong>of</strong> natureare <strong>of</strong> critical importance for conservationmanagement and planning. Muruwirriis an excellent example <strong>of</strong> this becausethe site including the DhambaliyaChannel has been earmarked for futureconservation work. Dhimurru and partnerssuch as the Aboriginal <strong>Areas</strong> ProtectionAuthority (AAPA) and Natural ResourcesEnvironment and the Arts (NRE-TA) are planning a mapping exercise tobetter understand the cultural and naturalheritage in the area. This mapping exerciseis part <strong>of</strong> the programme to workon the sea country plan, and combinesand builds on existing management pro-38

Establishing plots for coral reef monitoringgrammes at Dhimurru such as turtle recoveryand satellite tracking, marine debrissurveys, participation in the CarpentariaGhost Nets Programme, ethno-botanicalsurvey <strong>of</strong> Melville Bay, coral monitoring,informal surveillance and the provision<strong>of</strong> expert advice (Yunupingu &Muller 2007). As efforts turn towardsmapping the seabed, due care has to betaken to ensure that sacred sites andother cultural values are respected (seeimage in p. 39).One <strong>of</strong> the ways <strong>of</strong> adapting to culturalconditions is to test equipment and approachesin less culturally sensitive areasfirst, showing people the proposedtechniques so they can see if they areacceptable or not (see image in p. 35).As mapping also involves the consentand cooperation <strong>of</strong> the 20 clans representedby Dhimurru, reaching consensuson the work may not be an issue,though bureaucratic issues such as signingan agreement between all the organisationsinvolved may prove virtually impossiblefor practical reasons. In moderntimes, companies and government departmentsneed documents to sign <strong>of</strong>fthe job, and establishing a Memorandum<strong>of</strong> Understanding (MoU) signed byfacilitators and key staff rather than theTraditional Owners <strong>of</strong> all 20 clans usuallyserves as a solution. In addition, Dhimurruhas developed a scientific protocoloutlining the responsibilities <strong>of</strong> the researchersand partner organisations interms <strong>of</strong> sharing the benefits <strong>of</strong> their researchand addressing issues <strong>of</strong> IntellectualProperty Rights (IPR). <strong>The</strong> agreementalso enforces cultural protocolsand can be seen as induction training forBalanda to learn about proper behaviourin working and communicating withYolngu culture.Talking about sacred sites, NhullunThrough experience, Yolngu are politicallyaware <strong>of</strong> the importance <strong>of</strong> fosteringeffective ways <strong>of</strong> achieving reconciliationand cultural understanding. <strong>The</strong> Dhimurruhomelands are the birthplace <strong>of</strong> Aus-39

tralia’s most famous Aboriginal musicband: Yothu Yindi. At the height <strong>of</strong> itspopularity, the band was instrumental inbringing issues such as recognition forculture and land rights to the forefront <strong>of</strong>mainstream Australian society. <strong>The</strong> bandproduced songs in Yolngu and Englishwith titles like “Treaty”, “Tribal Voice” and“Mainstream”. <strong>The</strong> band has an internationalreputation, having toured extensivelyabroad, establishing relationships withother indigenous people’s organisationsaround the world and forming the YothuYindi Foundation. Another example <strong>of</strong>mainstream musical exposure for theDhimurru community was the recent cooperationwith popular Australian folk rockartist, Xavier Rudd, which brought the reenactment<strong>of</strong> the Galtha Bunggul and theimportance <strong>of</strong> Nhulun as a sacred site tothe attention <strong>of</strong> the Australian people.Xavier Rudd visited Northeast ArnhemLand and recorded a song called “LandRights” with outstanding Yolngu artistsand musicians which was included on his2007 album White Moth. <strong>The</strong> song, whichwas inspired by the history and culturalsignificance <strong>of</strong> Nhulun, has once againcarried the message <strong>of</strong> Yolngu people tothe broader Australian public in a very effectiveand engaging way.Culturally, Nhulun is an interesting example<strong>of</strong> the ongoing need to engage in publicoutreach and cross-cultural education,as the interpretive signage is regularly vandalised.This need is felt and recognisedas a priority by each generation <strong>of</strong> Yolngupeople, and expressed thus by Dhimurru’sdirector, Djawa Yunupingu:“Here in Northeast Arnhem Land wehave a very strong culture. We feel thepain <strong>of</strong> the land as it was felt through theeyes <strong>of</strong> the elders and we feel stronglyagain because the land is important tous; we feel the land, we sing the landwhen we care for the land and respectthe land” (Dhimurru 2007).From a management perspective, Nhulundemands continuous attention. <strong>The</strong>refore,Dhimurru is considering takingmeasures against the destruction <strong>of</strong> thesignage. <strong>The</strong> management options underconsideration range from replacingthe signage with more sturdy and damage-resistantsignage to installing a permanentdigital surveillance camera. Anotheroption would be to make effectiveuse <strong>of</strong> policy measures —for example,by penalising trespassers with the $AUS1000 fine foreseen by the <strong>Sacred</strong> SitesAct. Less rigorous options might includelimiting access by excluding vehiclesfrom the top <strong>of</strong> Nhulun. This could becombined with increased surveillanceand patrols which would enable <strong>of</strong>fendersto be reported to the police.Conclusions andrecommendationsDhimurru has acquired extensive experience<strong>of</strong> managing sacred natural sitesfrom a Yolngu and Western perspective.As Dhimurru’s management is guidedby perspectives central to Yolngu culture,spiritual and cultural values are always<strong>of</strong> primary concern to natural values.A number <strong>of</strong> universal lessons canbe extracted from this broad experiencewhich could be <strong>of</strong> use to indigenouspeoples, managers and policy makersdealing with sacred sites:40