Teachers for All â GCE policy briefing (566KB) - VSO

Teachers for All â GCE policy briefing (566KB) - VSO

Teachers for All â GCE policy briefing (566KB) - VSO

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

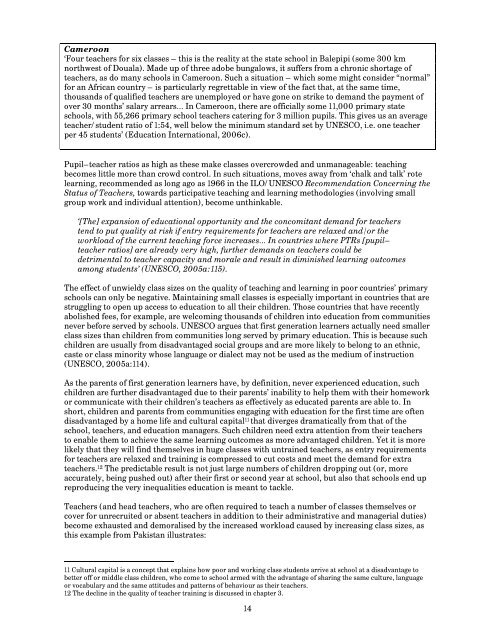

Cameroon‘Four teachers <strong>for</strong> six classes – this is the reality at the state school in Balepipi (some 300 kmnorthwest of Douala). Made up of three adobe bungalows, it suffers from a chronic shortage ofteachers, as do many schools in Cameroon. Such a situation – which some might consider “normal”<strong>for</strong> an African country – is particularly regrettable in view of the fact that, at the same time,thousands of qualified teachers are unemployed or have gone on strike to demand the payment ofover 30 months’ salary arrears… In Cameroon, there are officially some 11,000 primary stateschools, with 55,266 primary school teachers catering <strong>for</strong> 3 million pupils. This gives us an averageteacher/student ratio of 1:54, well below the minimum standard set by UNESCO, i.e. one teacherper 45 students’ (Education International, 2006c).Pupil–teacher ratios as high as these make classes overcrowded and unmanageable: teachingbecomes little more than crowd control. In such situations, moves away from ‘chalk and talk’ rotelearning, recommended as long ago as 1966 in the ILO/UNESCO Recommendation Concerning theStatus of <strong>Teachers</strong>, towards participative teaching and learning methodologies (involving smallgroup work and individual attention), become unthinkable.‘[The] expansion of educational opportunity and the concomitant demand <strong>for</strong> teacherstend to put quality at risk if entry requirements <strong>for</strong> teachers are relaxed and/or theworkload of the current teaching <strong>for</strong>ce increases… In countries where PTRs [pupil–teacher ratios] are already very high, further demands on teachers could bedetrimental to teacher capacity and morale and result in diminished learning outcomesamong students’ (UNESCO, 2005a:115).The effect of unwieldy class sizes on the quality of teaching and learning in poor countries’ primaryschools can only be negative. Maintaining small classes is especially important in countries that arestruggling to open up access to education to all their children. Those countries that have recentlyabolished fees, <strong>for</strong> example, are welcoming thousands of children into education from communitiesnever be<strong>for</strong>e served by schools. UNESCO argues that first generation learners actually need smallerclass sizes than children from communities long served by primary education. This is because suchchildren are usually from disadvantaged social groups and are more likely to belong to an ethnic,caste or class minority whose language or dialect may not be used as the medium of instruction(UNESCO, 2005a:114).As the parents of first generation learners have, by definition, never experienced education, suchchildren are further disadvantaged due to their parents’ inability to help them with their homeworkor communicate with their children’s teachers as effectively as educated parents are able to. Inshort, children and parents from communities engaging with education <strong>for</strong> the first time are oftendisadvantaged by a home life and cultural capital 11 that diverges dramatically from that of theschool, teachers, and education managers. Such children need extra attention from their teachersto enable them to achieve the same learning outcomes as more advantaged children. Yet it is morelikely that they will find themselves in huge classes with untrained teachers, as entry requirements<strong>for</strong> teachers are relaxed and training is compressed to cut costs and meet the demand <strong>for</strong> extrateachers. 12 The predictable result is not just large numbers of children dropping out (or, moreaccurately, being pushed out) after their first or second year at school, but also that schools end upreproducing the very inequalities education is meant to tackle.<strong>Teachers</strong> (and head teachers, who are often required to teach a number of classes themselves orcover <strong>for</strong> unrecruited or absent teachers in addition to their administrative and managerial duties)become exhausted and demoralised by the increased workload caused by increasing class sizes, asthis example from Pakistan illustrates:11 Cultural capital is a concept that explains how poor and working class students arrive at school at a disadvantage tobetter off or middle class children, who come to school armed with the advantage of sharing the same culture, languageor vocabulary and the same attitudes and patterns of behaviour as their teachers.12 The decline in the quality of teacher training is discussed in chapter 3.14