Meyer-Villages and Buddhist Monasteries in China.pdf

Meyer-Villages and Buddhist Monasteries in China.pdf

Meyer-Villages and Buddhist Monasteries in China.pdf

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Arch. 8 Comport. / Arch. 8 Behav.. Vol. 9, no. 2, p. 227-238 (1993)Rural <strong>Villages</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Monasteries</strong>:Contrast<strong>in</strong>g Spatial Orientations <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>aJeffrey F. <strong>Meyer</strong>Department of Religious StudiesUniversity of North Carol<strong>in</strong>a at CharlotteCharlotte, North Carol<strong>in</strong>a 28223l7.S.ASummaryThis article is an exam<strong>in</strong>ation of two dist<strong>in</strong>ct but <strong>in</strong>terrelated aspects of the plann<strong>in</strong>gof the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese <strong>Buddhist</strong> monastery compound, "place" refer<strong>in</strong>g to the specificityof elements <strong>in</strong> the monastic structure, "space" to symbolic elements which express theuniversality of <strong>Buddhist</strong> ideology. In one sense, the tension between these two elementsis a replication of the tension <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>teraction between a culture-transcend<strong>in</strong>g,universal Buddhism, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous Ch<strong>in</strong>ese factors which Buddhism had to confrontas a foreign importation <strong>in</strong>to a xenophobic culture.ResumeL'article exam<strong>in</strong>e deux aspects dist<strong>in</strong>cts, mais <strong>in</strong>terdkpendants, de la manibre dontles monastbres bouddhiques ch<strong>in</strong>ois sont amtnagbs, le terme "lieu" se rCfCrant a la spCcificitCdes ClCments de la structure monastique et celui d"'espaceW aux ClCments symboliquesexprimant I'universalitC de I'idCologie bouddhique. En un sens, la tension entreces deux ClCments reproduit la tension et I'<strong>in</strong>teraction entre un bouddhisme universel,non reliC A une culture spkcifique, et des facteurs <strong>in</strong>dighes ch<strong>in</strong>ois auxquels lebouddhisme a dli s'affronter titre "d'importation Ctrangbre" dans une' culture xCnophobe.1. Introduction"The depth of this immense sea of <strong>in</strong>dividuals has kept the form of a family,<strong>in</strong> an unbroken l<strong>in</strong>e from the earliest days. Every man here feels that he isboth son <strong>and</strong> father, among thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> tens of thous<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> is aware ofbe<strong>in</strong>g held fast by the people around him <strong>and</strong> the dead below him <strong>and</strong> the peopleto come, like a brick <strong>in</strong> a wall. He holds. Every man knows that he is noth<strong>in</strong>gapart from this composite earth, <strong>and</strong> outside the miraculous structure of his ancestors."(Valtry, 1962, 374)ValCry went off to Asia as a young man, without much knowledge of Ch<strong>in</strong>esehistory <strong>and</strong> culture, but quickly identified the essence of it all. Rootedness on the l<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> a sense of family solidarity are requisites <strong>in</strong> rural Ch<strong>in</strong>a, the very def<strong>in</strong>ition ofwhat it means to be a person <strong>in</strong> that patriarchal culture.' People <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> are the twoThe view I will be present<strong>in</strong>g is that of the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese male <strong>and</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> monk. I th<strong>in</strong>k that theanalysis of domestic <strong>and</strong> monastic space from a female perspective would yield some remarkabledifferences.

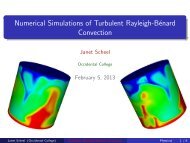

Rural <strong>Villages</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Monasteries</strong>: Contrast<strong>in</strong>g Spatial Orientations <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a 2291992, 1-2). There is an obvious relationship here between the Euro-American <strong>in</strong>dividualism<strong>and</strong> the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese communalism.The description which follows is generalized <strong>and</strong> over simplified. There are <strong>in</strong>fact a great many patterns of spatiallsocial organization <strong>in</strong> rural Ch<strong>in</strong>a, sometimeseven <strong>in</strong> one small area (Harrell, 1987). But despite the variation <strong>in</strong> detail there is aconsistent body of pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, of conceptual congruencies which can be discerned. My<strong>in</strong>tent <strong>in</strong> giv<strong>in</strong>g this general description is simply to suggest how radical was the transitionfrom ord<strong>in</strong>ary rural life to monastic life through a contrast of the fundamentallydifferent architecture <strong>and</strong> spatial concepts expressed <strong>in</strong> each.The village spatial sense <strong>in</strong>cludes two <strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>g systems. The first is the visiblel<strong>and</strong>scape, which I will call planar or horizontal. The second <strong>in</strong>cludes the <strong>in</strong>visibleupper <strong>and</strong> lower worlds, which together with the first make up the tri-storied universe.The vertical <strong>and</strong> horizontal worlds <strong>in</strong>tersect at many places <strong>in</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>scape, <strong>and</strong> these<strong>in</strong>tersections mark the power po<strong>in</strong>ts which def<strong>in</strong>e the "sacred geography" of the ruralCh<strong>in</strong>ese person (fig. 1). Besides these, there is a third system, geomancy Ifengshui),which also describes "power centres" <strong>in</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>scape (Fan, 1992). To consider thecomplexity of geomantic concepts, however, would take us far beyond the scope ofthis essay.Upper Realm: Kunlun MI.Western Paradise, ctc. /Gods (Tiangong, Jade Emperor)Shnngdi, etc.Ancestors-Ghosts/ancestorsFig. 1World View of Rural Ch<strong>in</strong>aLa vue du monde caracteristique de la Ch<strong>in</strong>e rurale

232 Jeffrey F. <strong>Meyer</strong>longer exists to worship the god of heaven, but the worship of greater spirits is stilltaken care of by Taoist <strong>and</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> priests. However, these functionaries are "outsidethe village," <strong>and</strong> are related to village religion only <strong>in</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g outside specialists calledto perform needed rituals, particularly funerals <strong>and</strong> temple festivals (Jordan, 1972, 30;Knapp, 1992, 10).It has become accepted that the three categories of spirits traditionally respectedby rural Ch<strong>in</strong>ese are gods, ghosts <strong>and</strong> ancestors (Freedman, 1958; Jordan, 1972; Ahern,1973; Eastman, 1988). Yet these are not hard <strong>and</strong> fast dist<strong>in</strong>ctions. Gods can be ancestors<strong>and</strong> vice versa, ghosts are "someone else's ancestors," or "untended ancestors,"<strong>and</strong> thus malign (Weller, 1987, 65; Eastman, 1988, 43). We have seen the power centreswhere the gods <strong>and</strong> ancestors of the vertical realms imp<strong>in</strong>ge upon the geography ofthe horizontal realm: the kitchen stove, the family altar, the l<strong>in</strong>eage hall, the shr<strong>in</strong>e ofthe earth god, <strong>and</strong> the temple of the village or market town. There rema<strong>in</strong> the ghosts,who can appear anywhere, <strong>and</strong> whose presence is most feared. They are h<strong>and</strong>led <strong>in</strong> twoways: with compassion, on the one h<strong>and</strong> by be<strong>in</strong>g fed, especially dur<strong>in</strong>g the seventhlunar month when they were believed to have the freedom to leave their underworldprisons <strong>and</strong> roam about the earth. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, they were bribed with "spiritmoney," bought off <strong>and</strong> hopefully expelled from home <strong>and</strong> village. When offer<strong>in</strong>gs offood <strong>and</strong> money were made, it was always done outside the home <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the larger ritesof the seventh month, outside the temple or village (Weller, 1987,72).Thus the outermost realm of the country folk's immediate experience was"outside the bamboo walls" which circled each community. It was dangerous becauseit was <strong>in</strong>habited by human strangers, b<strong>and</strong>its, beggars, <strong>and</strong> their <strong>in</strong>visible counterparts,the ghosts (Wolf, 1974, 175; Jordan, 1972, 51-53). The graves of ancestors wereplaced <strong>in</strong> this region, <strong>and</strong> although they were tended once a year at the Q<strong>in</strong>gm<strong>in</strong>gspr<strong>in</strong>g festival, they were otherwise avoided because ghosts hover about the graves.Ideally the graves were placed north of the village accord<strong>in</strong>g to the best geomanticCfengshui) pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, both for the comfort of the ancestors buried there <strong>and</strong> the goodfortune of the liv<strong>in</strong>g family.Figure 1 is meant to summarize the spatial orientation of a "typical" ruralCh<strong>in</strong>ese, hisher locus <strong>in</strong> the spiritual geography of the horizontal <strong>and</strong> vertical worlds,together with the power centres: family altar, earth god shr<strong>in</strong>e, village temple or itsequivalent, <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ally the graves of ancestors. As human, the <strong>in</strong>dividual is conf<strong>in</strong>ed tothe horizontal world, except when, through the help of a spirit medium, the human cantravel to the heavens or to the underworld to contact a god or ancestor. Of course thehuman be<strong>in</strong>g also feels the power of the other realms because the gods, ghosts, <strong>and</strong> ancestorsall have access to the earthly realm <strong>and</strong> can affect the human's life. (The gods'power is felt <strong>in</strong> all three realms, the ancestors can be conceived to be present either <strong>in</strong>the upper or underworld, but have access to the earth as well; the ghosts live <strong>in</strong> the underworld,have access to the earth but not the upper realm.)The experience described is hierarchical, one of embeddedness <strong>in</strong> overlapp<strong>in</strong>grealms of power. Thus the villager's spiritual experience perfectly mirrors his political<strong>and</strong> social experience, both of which are also of fixity <strong>in</strong> overlapp<strong>in</strong>g fields of power<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence. The villager is most "at home" <strong>in</strong> the domestic centre of the concentricfields. As he moves out from his centre, his sense of security "th<strong>in</strong>s," s<strong>in</strong>ce he ismore dependent on the power <strong>and</strong> control of be<strong>in</strong>gs, both human <strong>and</strong> spiritual, overwhich he has less <strong>and</strong> less <strong>in</strong>fluence. If his major desires are food, money <strong>and</strong> offspr<strong>in</strong>g,it is because these give him greater security at his centre, the home, <strong>and</strong> greater

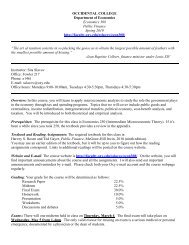

Rural <strong>Villages</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Monasteries</strong>: Contrast<strong>in</strong>g Spatial Orientations <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a 233<strong>in</strong>fluence as he moves out toward the periphery. He has security only as a componentof the whole network of power, human <strong>and</strong> spiritual, "like a brick <strong>in</strong> the wall."3. The Spatial Orientation of the <strong>Buddhist</strong> MonasteryWhen a new c<strong>and</strong>idate enters the monastery, the <strong>Buddhist</strong> Order takes steps to reorienthim to a new underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of reality. The ritual <strong>in</strong>itiation of the novice <strong>in</strong>dicatesthis, as he is stripped of his secular clothes <strong>and</strong> vested <strong>in</strong> a dist<strong>in</strong>ctive robe, hishead is shaved, his skull marked with the scars of burn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cense, <strong>and</strong> he is given anew name. He has clearly committed himself to chujia, leave home <strong>and</strong> family. Henow takes refuge, not <strong>in</strong> the security of his family, liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> dead, but <strong>in</strong> "Buddha,Dharma (<strong>Buddhist</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g) <strong>and</strong> Sangha (<strong>Buddhist</strong> community)." The ab<strong>and</strong>onment ofnatal family is confirmed when he gives up his family name <strong>and</strong> takes the surnameShi, a practice which goes back to the first centuries of Buddhism's <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>in</strong>toCh<strong>in</strong>a. As Dao An (313-85 C.E.) said, "When the four rivers enter the sea, theirnames can no longer be found. When the four surnames leave their families (chujia),they are called Shi" (Huang, 1990,25).In order to effect this radical transformation <strong>in</strong> the monk, the monastic structurereoriented the novice both spatially <strong>and</strong> temporally. Someth<strong>in</strong>g of the temporal restructur<strong>in</strong>gis described <strong>in</strong> an essay by Miller (1979). The scope of my article will allowonly a brief summary of the spatial restructur<strong>in</strong>g, as it is suggested by the plann<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> layout of the temple compound. For a more detailed account of how themonastic structure recapitulates the total cosmology, I refer the reader to my earlier article(<strong>Meyer</strong>, 1992). Here I wilI focus only on those features which contrast with thevillage world view described above.\ I *Sambhoeakava -- Realm of FormBuddhas, BodhisattvasOther transcendent be<strong>in</strong>gs/Nirmanaluva - Realm of SensesHeavens-thegods, tutdary deities,ancestors/Human Realm -humans, animals\\Fig. 3Levels of Reality <strong>in</strong> Mahayana BuddhismLes niveaux de la realit6 dans le Bouddhisrne Mahayana

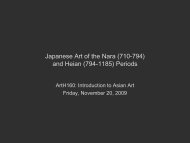

Rural <strong>Villages</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Monasteries</strong>: Contrast<strong>in</strong>g Spatial Orientations <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>aGraves<strong>and</strong>Burn<strong>in</strong>g TowerShakyamunlGuanylnMonks Chantofficesaoshl (Heal<strong>in</strong>g Buddha)Women'sDorm~torlesUpsta~rsWmtoMen'sDorm~tor~esUpstacnChantyEarth GodTudlgongLargeFurnaceG~ant BuddhaStatueLionFig. 4Po L<strong>in</strong> Monastery, Lantau Isl<strong>and</strong>, Hong KongLe monasthre de Po L<strong>in</strong>, lie de Lantau, Hong Kong

236 Jeffrey F. <strong>Meyer</strong><strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dividual must journey <strong>in</strong>ward to f<strong>in</strong>d it. He needs no mediators. On the peripheryor outside the walls are ranged the lesser powers of the samsaric world.A pailou (three part ceremonial arch) marks the entry to the monastic grounds.The path from there to the ma<strong>in</strong> gate is slightly eccentric, to discourage ghosts whomthe Ch<strong>in</strong>ese believed moved <strong>in</strong> straight l<strong>in</strong>es. The t<strong>in</strong>y shr<strong>in</strong>e to Tudigong, the earthgod, is outside the gate to the left as you enter. Although Po-l<strong>in</strong> does not have them,some monasteries have built ponds for releas<strong>in</strong>g life <strong>and</strong>lor barns for animals purchasedfrom the market place so that their lives would be spared. These too would be outsidethe walls of the compound. F<strong>in</strong>ally, graves, <strong>in</strong> this case those of monastic forebears,would be found outside <strong>and</strong> ideally to the north of the monastery. Po-l<strong>in</strong> has clustersof graves above <strong>and</strong> beh<strong>in</strong>d the ma<strong>in</strong> compound, <strong>and</strong> a "burn<strong>in</strong>g tower" where the cremationsare done to prepare the ashes for burial. Thus ranged all around the perimeterof the temple compound are the be<strong>in</strong>gs of samsaric existence: gods, ancestors, ghosts,animals, <strong>and</strong> worldly human be<strong>in</strong>gs.The ma<strong>in</strong> entrance to the compound leads one through the Hall of HeavenlyK<strong>in</strong>gs, which is clearly a place of transition. The first statue is that of Milofo, the FatBuddha. Orig<strong>in</strong>ally identified as Maitreya, the Buddha who waits <strong>in</strong> Tushita (one ofthe highest samsaric heavens), became identified with Budai dur<strong>in</strong>g the medieval period<strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a. Budai was a popular figure whose sagacity was hidden under a ludicrous fatexterior <strong>and</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese often see him as a br<strong>in</strong>ger of worldly bless<strong>in</strong>gs. Milofo as Budaiis part of the samsaric <strong>and</strong> visible world, nirmanakaya. Housed <strong>in</strong> the same build<strong>in</strong>gwith him are the locapalas, for whom the hall is named. They are the k<strong>in</strong>gs of thefour card<strong>in</strong>al directions, still part of the world of transformation, but of a higher order.They show that Buddhism's <strong>in</strong>fluence reaches to every part of the visible cosmos.Back to back with Milofo <strong>and</strong> beh<strong>in</strong>d a screen is Weito, the guardian of the Dharma,who is described <strong>in</strong> one of the sutras as always "fac<strong>in</strong>g the Buddha," so he is alwaysplaced fac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ward (Prip-Moeller, 1982, 30). He is a general <strong>in</strong> the army of thesouthern k<strong>in</strong>g.After cross<strong>in</strong>g the courtyard, one comes to the ma<strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g, usually called thedaxiongbaodian, or Precious Hall of the Great Hero. At Po-l<strong>in</strong> this is a two storeybuild<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> both levels embody the higher reality of samghogakaya. In the lowerstory, the major altar is dedicated to the Bodhisattva Guany<strong>in</strong> (Goddess of Mercy),who, as is usual <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a, is shown <strong>in</strong> female form. Flank<strong>in</strong>g her on either side aretwo other important bodhisattvas, Wenshu <strong>and</strong> Puxian. Along the back wall are the500 lohans, enlightened monks.Upstairs is the real focus <strong>and</strong> centre of the temple complex, the altar upon whichis placed the stature of Shakyamuni Buddha accompanied by Omitofo (Amitabha,Buddha of the Pure L<strong>and</strong>) <strong>and</strong> Yaoshi, always popular <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a as the Heal<strong>in</strong>g Buddha.This altar symbolizes the culm<strong>in</strong>ation of monastic experience, for the central statue ofthe temple recapitulates the entire <strong>in</strong>ward journey from the samsaric world ofnirmanakaya to the ultimate reality of the dharmakaya. Identified as Shakyamuni, thecentral image can be understood as the historical Buddha who lived <strong>in</strong> samsara dur<strong>in</strong>gthe sixth <strong>and</strong> fifth centuries BCE. Yet he is shown <strong>in</strong> a glorious <strong>and</strong> blissful form(sambhogakaya) as a div<strong>in</strong>e god-like Buddha, surrounded by bodhisattvas, arhats,lohans, devas, angelic <strong>and</strong> mythical be<strong>in</strong>gs, just as he is described <strong>in</strong> the most popularMahayana sutras. And f<strong>in</strong>ally, for those who by meditation can penetrate appearances,the image also po<strong>in</strong>ts to that which cannot be told <strong>in</strong> worldly terms or shown <strong>in</strong>physical form, the ultimate reality, dharmakaya. As every educated <strong>Buddhist</strong> knows,

Rural <strong>Villages</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Monasteries</strong>: Contrast<strong>in</strong>g Spatial Orientations <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a 237this ultimate reality is not an external reality, but resides <strong>in</strong> every person's x<strong>in</strong>(heart'm<strong>in</strong>d). Though expressed externally <strong>in</strong> architecture <strong>and</strong> iconography, the actualjourney is <strong>in</strong>ward. As the Zen say<strong>in</strong>g goes, jian x<strong>in</strong>g, cheng fo, "Look at your <strong>in</strong>nernature <strong>and</strong> become Buddha."Emily Ahern (1973, 179) describes a funeral procession <strong>in</strong> Taiwan, <strong>in</strong> which thetablet of the deceased is carried to the grave <strong>in</strong> a wooden bushel, which also conta<strong>in</strong>sfive or more k<strong>in</strong>ds of gra<strong>in</strong>s or seeds, several Taiwanese co<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> a number of nails.These three th<strong>in</strong>gs represent the ord<strong>in</strong>ary long<strong>in</strong>gs of the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese people: a good harvest<strong>and</strong> sufficient food, wealth <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial success, <strong>and</strong> children (the word for nails,d<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> for male children are homophones), "the most fundamental <strong>and</strong> axiomaticgoals of Taiwanese life." These three desires make clear just how radical a reorientationBuddhism proposes to accomplish. The monks fast, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g their mastery ofthe crav<strong>in</strong>g for food. They undertake a life of poverty <strong>and</strong> celibacy, show<strong>in</strong>g their contemptfor wealth, sex <strong>and</strong> family. The direction of the journey toward Reality has beenreversed, <strong>in</strong>teriorized, <strong>and</strong> a radical reorientation has (ideally) taken place. As Yang(1969, 14) describes it: "each monastery or nunnery represented a m<strong>in</strong>iature sacred orderof life different from the secular social order, presumed to be perfect, capable of correct<strong>in</strong>gall the imperfections of the material world <strong>and</strong> designed for sav<strong>in</strong>g men from everlast<strong>in</strong>gsuffer<strong>in</strong>g."Weller (1987, 113-1 14) summarizes some of the major differences between<strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>and</strong> popular traditions. The monks have turned their back on the omnipresenthierarchy of secular bureaucracy. Their pursuit of the ultimate reality is not only <strong>in</strong>ward,but egalitarian. Whether wealthy or poor, educated or illiterate, m<strong>and</strong>ar<strong>in</strong> orfarmer, male or female, what mattered was spiritual achievement. Their gods are notanthropomorphic like those of conventional worship, but have "transcended the physical<strong>and</strong> emotional limits of humanity." This can be seen <strong>in</strong> the ritual offer<strong>in</strong>gs (meats<strong>and</strong> alcohol, common offer<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> the village rites, are not offered to the Buddhas <strong>and</strong>Bodhisattvas), as well as <strong>in</strong> the architecture of their temples <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the iconography ofthe images. F<strong>in</strong>ally, I would add another difference: the idea that nature is reality <strong>in</strong>traditional Ch<strong>in</strong>ese cosmology, while <strong>in</strong> Buddhism nature is illusion. To reach the ultimatelyreal, one must transcend it.Just as the structure of a home expressed the place of a person <strong>in</strong> space <strong>and</strong> time,so the <strong>Buddhist</strong> monastery, by means of its orientation <strong>and</strong> structure, located a person<strong>in</strong> the vast stretches of <strong>Buddhist</strong> times <strong>and</strong> among the countless universes of <strong>Buddhist</strong>space. It also paradoxically centred him. As the devotee moved from the secular worldoutside the monastic compound, he crossed a threshold at the outer gate which began aspiritual journey or pilgrimage to a def<strong>in</strong>ite centre. This centre was located at <strong>and</strong>symbolized by the large Buddha image <strong>in</strong> the centre of the Precious Hall of the GreatHero. Beh<strong>in</strong>d this, the ma<strong>in</strong> hall of the complex, were build<strong>in</strong>gs of progressively lessimportance. While the ancestral altar was the centre of the home, the ancestors of themonks, the abbots <strong>and</strong> sa<strong>in</strong>ts of the past, were placed to the rear of the compound, <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong> the case of Po-l<strong>in</strong>, off the central axis. The structure <strong>in</strong>dicated by the monasticplan, therefore, is the circle or sphere, with the centre the place of greatest power,sacrality <strong>and</strong> permanence, <strong>and</strong> the periphery the place of secularity, commonness, animality,demons <strong>and</strong> ghosts.Although the ord<strong>in</strong>ary worshipper who visited the monastery to j<strong>in</strong> xiang(present <strong>in</strong>cense) would have experienced to some degree this new sense of space <strong>and</strong>time, the more powerful experience was reserved for those who entered the monastic

238 Jeffrey F. <strong>Meyer</strong>complex to stay. They gave up secular life, family, birthplace <strong>and</strong> entered a new realmas novices. The enter<strong>in</strong>g of sacred space was re<strong>in</strong>forced by the ritual changes whichwere physical, psychic <strong>and</strong> spiritual. It is not too dramatic to say that old patternswere shattered, <strong>and</strong> the novices were thrust <strong>in</strong>to a powerful period of "disorientation,"which changed the way they experienced their own presence <strong>in</strong> time <strong>and</strong> space.Today <strong>in</strong> the therapeutic age we tend to th<strong>in</strong>k of behavioural change as precededby right th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. If the dysfunctional person can be helped to be consciousness oftheir own plight, if their th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g can change, then they can learn to behave morefunctionally. The <strong>Buddhist</strong> approach was the opposite. First, the environment <strong>and</strong>rhythms of life were changed by the <strong>in</strong>duction <strong>in</strong>to the monastic community, then behaviourwould change, <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ally, the <strong>in</strong>ner world would change. After be<strong>in</strong>g disoriented,the monk or nun eventually achieved a new orientation, no longer trapped, like abrick <strong>in</strong> the old wall of family, hierarchy, <strong>and</strong> bureaucracy. Such at least was the ideal,the <strong>in</strong>tentionality of the monastic plan.BIBLIOGRAPHYAHERN, E. (1973). "The Cult of the Dead <strong>in</strong> a Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Village" (Stanford University Press. Stanford,CA).CORLESS, R. (1989). "The Vision of Buddhism" (Paragon House, New York).EASTMAN, L. (1988), "Family, Fields, <strong>and</strong> Ancestors: Constancy <strong>and</strong> Change <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a's Social <strong>and</strong>Economic History" (Oxford, New York).FAN, W. (1992), Village Fengshui Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese L<strong>and</strong>scapes: The Village as Place (Knapp, R.,Ed.)(University of Hawaii, Honolulu), 35-45.FEI, X. (1992). "From the Soil: The Foundations of Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Society" (University of California, Berkeley).FREEDMAN, M. (1958), "L<strong>in</strong>eage Organization <strong>in</strong> southeastern Ch<strong>in</strong>a" (Athlone, London).FEUCHTWANG, S. (1974). Domestic <strong>and</strong> communal Worship <strong>in</strong> Taiwan, Religion <strong>and</strong> Ritual <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>eseSociety (Wolf, A.,Ed.) (Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA), 105-129.FEUCHTWANG, S. (1992). Boundary Ma<strong>in</strong>tenance: Territorial Altars <strong>and</strong> Areas <strong>in</strong> Rural Ch<strong>in</strong>a, SacredArchitecture <strong>in</strong> the Traditions of India, Ch<strong>in</strong>a, Judaism <strong>and</strong> Islam (Lyle, E., Ed.) (Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh UniversityPress, Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh), 93-109.HAMMOND, J. (1992), Xiqi Village, Guangdong: Compact with Ecological Plann<strong>in</strong>g. Ch<strong>in</strong>eseL<strong>and</strong>scapes: The Village as Place (Knapp, R., Ed.)(University of Hawaii, Honolulu), 95-105.HARRELL, S. (1987). Social Organization <strong>in</strong> Hai-shan, The Anfhropology of Taiwanese Society (Ahern,E. & Gates, Eds.) (Cave Books, Taipei, Taiwan), 125-147.HUANG, C. (1990). "Zhongguo Fojiao shi" Wistory of Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Buddhism] (Cultural Arts, Shanghai).JORDAN, D. (1972), "Gods, Ghosts <strong>and</strong> Ancestors: The Folk Religion of a Taiwanese Village"(University of California, Berkeley).KNAPP, R. (1992), "Ch<strong>in</strong>ese L<strong>and</strong>scapes: The Village as Place" (University of Hawaii, Honolulu).MEYER, J. (1992). Ch<strong>in</strong>ese <strong>Buddhist</strong> Temples as Cosmograms, Sacred Architecture <strong>in</strong> the Traditions ofIndia, Ch<strong>in</strong>a, Judaism <strong>and</strong> Islam (Lyle, E., Ed.) (Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh University Press, Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh), 71-92.MILLER, A. (1979), The <strong>Buddhist</strong> Monastery as a Total Institution, Journal of Religious Sludies (Ohio), 7(1979) Fall, 15-29.PRIP-MOELLER, J. (1937, 1982). "Ch<strong>in</strong>ese <strong>Buddhist</strong> <strong>Monasteries</strong>" 3rd ed.(University of Hong KongPress, HK).VALERY, P. (1962). "The Yalu", History <strong>and</strong> Polilics (Matthews, J. Ed.) (trans. Denise Boll<strong>in</strong>gen Series45) (Pantheon, New York).WELLER, R. (1987), "Unities <strong>and</strong> Diversities <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Religion" (University of Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, Seattle).WOLF, A. (1974), "Religion <strong>and</strong> Ritual <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Society" (Stanford University, Stanford, CA).YANG, C.K. (1969). "Religion <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Society" (Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA).YANG, M.C. (1945), "A Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Village: Taitou, Shantung Prov<strong>in</strong>ce" (Columbia University Press, NewYork).