Behind the Scenes, Kenya IDP Report - Danish Refugee Council

Behind the Scenes, Kenya IDP Report - Danish Refugee Council

Behind the Scenes, Kenya IDP Report - Danish Refugee Council

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

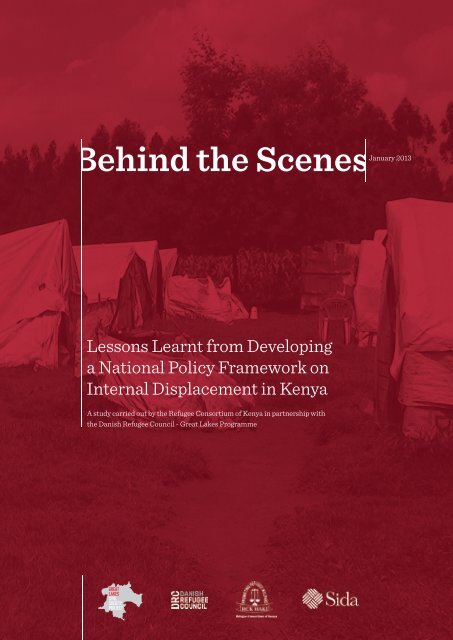

<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong>January2013Lessons Learnt from Developinga National Policy Framework onInternal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>A study carried out by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> Consortium of <strong>Kenya</strong> in partnership with<strong>the</strong> <strong>Danish</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong> - Great Lakes Programme

<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong>Lessons Learnt from Developinga National Policy Framework onInternal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>January 2013<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>I

AcknowledgementsThis documentation study was commissioned by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> Consortium of <strong>Kenya</strong> (RCK) and <strong>the</strong><strong>Danish</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong>’s Great Lakes Civil Society Project. The study was undertaken and compiled intwo phases. The first phase of collecting primary and secondary data, compiling <strong>the</strong> findings and writing<strong>the</strong> report was done by Davis M. Malombe. The second phase of writing and finalising <strong>the</strong> report was doneby Joseph Omolo in consultation with <strong>the</strong> Study Advisory Group (SAG).The process of conducting <strong>the</strong> study and <strong>the</strong> compilation of this final report immensely benefited from<strong>the</strong> guidance, review, support and supervision of <strong>the</strong> SAG. The SAG was made up of staff from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong>Consortium of <strong>Kenya</strong> (Lucy Kiama – Executive Director, Leila Muriithia – Senior Programme Officer,Rufus Karanja – Programme Officer, Ad-vocacy and Riva Jalipa - Associate Programme Officer, Advocacy)and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Danish</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong> (Alexandra Bilak – Programme Manager, Great Lakes CivilSociety Project and Pauline Wesolek – Programme Officer, Great Lakes Civil Society Project). The StudyAdvisory Group also played a key role in providing technical, logistical and administrative support for <strong>the</strong>study.RCK and DRC extend <strong>the</strong>ir gratitude to all <strong>the</strong> partners and members of <strong>the</strong> Protection Working Group onInternal Displacement, including those at <strong>the</strong> field level who were interviewed for <strong>the</strong> study. RCK thanksall <strong>the</strong> internally displaced persons who were interviewed for this study in Nakuru, Eldoret and Kitale.Their practical experience and knowledge significantly supported <strong>the</strong> findings of this study.Finally, RCK and DRC thank <strong>the</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> Government officials, in particular Michael Nyamai (MoSSP),Joseph Gitonga (MoJNCCA), Members of Parliament including Hon. Ekwe Ethuro as <strong>the</strong> Chair of <strong>the</strong>PSC, Hon. Sophia Abdi as <strong>the</strong> Chair of <strong>the</strong> LSWC and o<strong>the</strong>r international partners who agreed to be interviewedfor this study and who have been closely involved in <strong>the</strong> policy development process.II<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>III

List of AbbreviationsAcquired Immunodeficiency SyndromeAdvocacy Sub-Working GroupAfrican UnionChildren’s Legal Action NetworkCivil Society OrganisationsGreat Lakes Civil Society ProjectHuman Immunodeficiency VirusInternational Conference on <strong>the</strong> Great Lakes RegionInternational Displacement Monitoring CentreInternal Displacement Policy and Advocacy CentreInternally Displaced PersonsInternational <strong>Refugee</strong> Rights Initiative<strong>Kenya</strong> Human Rights Commission<strong>Kenya</strong> National Commission for Human Rights<strong>Kenya</strong>ns for Truth with Peace and JusticeLamu Port-Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Sudan-Ethiopia TransportLegal and Advocacy Sub-working GroupLand Sector Non-State ActorsLabour and Social Welfare CommitteeMinistry of Justice National Cohesion and Constitutional AffairsMinistry of State for Special ProgrammesNorth Frontier DistrictsNon-Governmental OrganisationsNorwegian <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong>Office of <strong>the</strong> Higher Commissioner for Human RightsProtection ClusterPost-Election ViolenceParliamentary Select Committee on <strong>the</strong> Resettlement of <strong>IDP</strong>s in <strong>Kenya</strong>Protection Working Group on Internal Displacement<strong>Refugee</strong> Consortium of <strong>Kenya</strong>The Office of <strong>the</strong> Representative of <strong>the</strong> Secretary-General on <strong>the</strong> Human Rights of <strong>IDP</strong>sSpecial Rapporteur on <strong>the</strong> Human Rights of <strong>IDP</strong>sTruth, Justice and Reconciliation CommissionUnited NationsUnited Nations High Commissioner for <strong>Refugee</strong>sUnited Nations Children’s FundUnited Nations Office Coordinating Humanitarian AffairsAIDSASWGAUCLANCSOsGCPHIVICGLRIDMC<strong>IDP</strong>AC<strong>IDP</strong>IRRIKHRCKNCHRKTPJLAPSSETLASWGLSNALSWCMoJNCCAMoSSPNFDsNGOsNRCOHCHRPCPEVPSCPWGIDRCKRSGSR/<strong>IDP</strong>sTJRCUNUNHCRUNICEFUNOCHAIV<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>V

ForewordInternal displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> has been described as a historical problem which has been exacerbatedby <strong>the</strong> lack of a comprehensive legal and policy framework to, at <strong>the</strong> least, recognise who an <strong>IDP</strong> is andwhere responsibilities lie. As a result, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>n Government has in most instances responded to <strong>the</strong>problem in an ad hoc and needs-based manner as opposed to a rights-based one that is premised on internationallyaccepted human rights standards.Following <strong>the</strong> devastating impact of <strong>the</strong> 2007/08 post-election violence in which over 1,300 personswere killed and over 600,000 o<strong>the</strong>rs internally displaced, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> Government, through <strong>the</strong> Ministryof State for Special Programmes (MoSSP) and in collaboration with humanitarian and non-state actors,embarked on <strong>the</strong> development of an <strong>IDP</strong> Policy. This policy was intended to help <strong>the</strong> Government betterprevent instances of internal displacement, to provide enhanced protection and assistance to internallydisplaced persons (<strong>IDP</strong>s) and to promote <strong>the</strong> achievement of durable solutions for <strong>IDP</strong>s. This initiativelater transformed into <strong>the</strong> development of legislation on internal displacement (<strong>IDP</strong> Bill, 2012).The development and lobbying process of <strong>the</strong>se frameworks has been prolonged and demanding on resources.The experience, however, has been rewarding in terms of both <strong>the</strong> near realisation of progressiveframeworks but also as a learning process for actors who have been instrumental in <strong>the</strong>se processes.The <strong>Kenya</strong>n experience is a commendable one, in that it has benefitted to a great extent from <strong>the</strong> immensesupport and collaboration from <strong>the</strong> Government. That is not to say that it has not had its fair share of challengesnor that it has not been without good fortunes. The documentation of this process is an importantone which could inform future advocacy strategies on policy development and is also a means of reflectionfor those who have been involved in <strong>the</strong> process.This study by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> Consortium of <strong>Kenya</strong> and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Danish</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong> (Great Lakes Civil SocietyProject) could not be any more timely, as signatories to <strong>the</strong> African Union Convention on <strong>the</strong> Protectionand Assistance to Internally Displaced Persons (Kampala Convention) seek to domesticate thisConvention.Dr. Chaloka BeyaniUN Special Rapporteur on<strong>the</strong> Human Rights of <strong>IDP</strong>sVI<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>VII

Table of ContentsAcknowledgementsList of AbbreviationsForewordTable of contentExecutive SummaryIIIVVIIIXXIChapter 1 Introduction 11.1. The <strong>Kenya</strong>n Context 11.2. The Political and Technical Processes Towards Drafting <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Policy 21.3. Purpose and Objectives of <strong>the</strong> Study 21.4. The Partnership between <strong>the</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> Consortium of <strong>Kenya</strong>and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Danish</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong> (Great Lakes Civil Society Project ) 21.5.1. Desk Review 31.5.2. Key Informant Interviews 31.5.3. Internal RCK Reflection 31.5.4. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework 41.5.5. Shortcomings of <strong>the</strong> Methodology 4Chapter 2 Setting <strong>the</strong> Scene 62.1. Causes of Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 62.1.1. Colonial and Post-Colonial Factors 62.1.2. Election-related Violence 62.1.3. Border and Resource Disputes Including Cattle Rustling and Banditry 72.1.4. Natural and Human Made Disasters 72.1.5. Development Projects and Displacement 72.2. Towards a Policy Framework 72.2.1. Development of an Overarching Policy Framework 82.2.2. Development of a Legislative Framework 82.2.3. Synchronising <strong>the</strong> Policy and Legislative Processes 82.2.4. Taking Stock of <strong>the</strong> Process 11Chapter 3 The Role of <strong>the</strong> PWGID: Added Valueof a National Coordination Mechanism 133.1. Institutional Responses to <strong>the</strong> Post-Election Violence in 2007/2008 133.2. Collective Responses within <strong>the</strong> PWGID 133.3. Key Achievements of <strong>the</strong> PWGID 143.4. Key Challenges 15Chapter 4 The Role of Civil Society 174.1. Identifying <strong>the</strong> Problem 174.2. Policy Choices 18VIII<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>IX

Executive Summary4.3. Policy Formulation 184.4. Policy Adoption 194.5. Policy Implementation 204.6. Policy Evaluation 204.7. Participatory Nature of <strong>the</strong> Policy Development Process 20Chapter 5: Navigating through a Tough Political Environment 235.1. Sensitivity of <strong>the</strong> Topic of Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 235.1.1. Post-election violence 2007 235.1.2. Ethnic Dimension 235.1.3. State responsibility for <strong>IDP</strong>s 245.2. Institutional context 245.2.1. Different Visions: The Executive versus Parliament 245.2.2. Private Member’s Bill 245.2.3. Engaging with Actors and Managing Interests 255.3. Impact of Changes in <strong>the</strong> Political Scene since 2007 255.3.1. Implementation of <strong>the</strong> 2010 Constitution 255.3.2. Proceedings at <strong>the</strong> International Criminal Court 265.3.3. Upcoming Elections 26Chapter 6: Lessons Learned and Recommendations 286.1. Lessons Learned 286.1.1. A Critical Mass of Local Actors 286.1.2. Coordination of Advocacy Work 286.1.3. Resource Mobilisation 286.1.4. Involvement of <strong>the</strong> Government 286.1.5. Adapting International Standards to Local Conditions 296.1.6. Creation and Utilisation of Networks and Personal Contacts 296.1.7. Timing 306.1.8. Inclusion and Participation 306.1.9. Institutional Weaknesses and Capacity Building for Actors 306.1.10. Flexibility, Concessions and Compromises 306.1.11. Local and External expertise 306.2. Recommendations to Countries Wishing to Engagein <strong>the</strong> Process of Developing a Policy on Internal Displacement 31<strong>Kenya</strong> is in <strong>the</strong> final stages of developing a Policy on internal displacement. Its legislature has recentlypassed a law to provide for <strong>the</strong> protection and provision of assistance to <strong>IDP</strong>s based on <strong>the</strong> provisions of<strong>the</strong> Great Lakes Protocol on <strong>the</strong> Protection and Assistance to Internally Displaced Persons (Great Lakes<strong>IDP</strong> Protocol) and <strong>the</strong> United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (Guiding Principles).Almost all countries within <strong>the</strong> Great Lakes Region 1 have a population of internally displaced personswhose displacement has been occasioned by a number of factors such as conflicts, natural and man-madedisasters and development projects. Despite this, most countries within <strong>the</strong> region lack a policy frameworkon internal displacement. At <strong>the</strong> moment, <strong>the</strong>re is growing momentum to establish a model frameworkbased on <strong>the</strong> Guiding Principles, <strong>the</strong> Great Lakes Protocol and African Union Convention for <strong>the</strong>Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention).This report is <strong>the</strong> result of a project commissioned by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> Consortium of <strong>Kenya</strong> and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Danish</strong><strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong>’s Great Lakes Civil Society Project, whose purpose was to capture and analyse <strong>the</strong>advocacy and engagement process that went into <strong>the</strong> preparation of <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Policy and Bill in <strong>Kenya</strong>. Byhighlighting <strong>the</strong> challenges and lessons learnt from <strong>the</strong> process, <strong>the</strong> outcome of <strong>the</strong> project should make auseful guide for discussions on advocacy strategies for forced migration policies at <strong>the</strong> regional and continentallevel.This report highlights a number of best practices based on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>n experience. These best practicesshould serve as a guide to persons involved in policy development on forced migration within <strong>the</strong> region.Some of <strong>the</strong> best practices may also be applicable to policy development work in o<strong>the</strong>r sectors locally andregionally. The best practices identified from <strong>the</strong> process revolved around issues like: creation of a criticalmass of actors; establishment of a national coordination mechanism; strategies for resource mobilisation;partnership with <strong>the</strong> government in <strong>the</strong> policy development process; adaptation of internationalprotection benchmarks to suit local conditions; creation and utilisation of networks; timing of policy developmentprocesses; participation in <strong>the</strong> process; identification of institutional weaknesses and building<strong>the</strong> capacity of actors to boost <strong>the</strong>ir participation in <strong>the</strong> process; need for flexibility on policy developmentoptions; and use of local and external expertise. Based on <strong>the</strong>se issues, <strong>the</strong> report offers a number of comprehensiverecommendations aimed at different actors.Appendices 33Bibliography 35Footnotes 37X<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>XI

Chapter 1:Introduction1.1. The <strong>Kenya</strong>n Context<strong>Kenya</strong> is in <strong>the</strong> final stages of developing a Policyon internal displacement. Its legislature has recentlypassed a law to provide for <strong>the</strong> protectionand provision of assistance to <strong>IDP</strong>s based on <strong>the</strong>provisions of <strong>the</strong> Great Lakes <strong>IDP</strong> Protocol on <strong>the</strong>Protection and Assistance to Internally DisplacedPersons and <strong>the</strong> United Nations Guiding Principleson Internal Displacement. The President assentedto <strong>the</strong> Bill on 31 st December 2012. 2Advocacy work in <strong>Kenya</strong> for <strong>the</strong> establishment ofa national policy on <strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s startedin April 2007 when <strong>Kenya</strong>n civil society organisations(CSOs), United Nations (UN) agencies andgovernment ministries working on <strong>IDP</strong> issuesestablished a task force on <strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s.The mandate of <strong>the</strong> taskforce included organisinga national conference on <strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>IDP</strong>sin November 2007, with a view to streng<strong>the</strong>ningmechanisms for immediate responses and advocatefor durable solutions for all categories of <strong>IDP</strong>s.Following <strong>the</strong> violence that erupted in 2007/ 2008,<strong>the</strong> National Disaster Operations Centre 3 , on behalfof <strong>the</strong> Government of <strong>Kenya</strong>, called upon humanitarianagencies to work towards mitigating<strong>the</strong> humanitarian crisis caused by <strong>the</strong> post-electionviolence. As a result, eleven clusters were establishedunder <strong>the</strong> UN system to facilitate rapidmobilisation of donor funding, to provide a mechanismfor coordinating humanitarian assistanceand to support government structures and helprestore <strong>the</strong>ir capacities.A national <strong>IDP</strong> Protection Cluster formed by <strong>the</strong>United Nations High Commissioner for <strong>Refugee</strong>s(UNHCR) was part of this cluster systemwith representation from more than 30 agenciesincluding <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Justice, NationalCohesion and Constitutional Affairs (MoJNC-CA), <strong>the</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> National Commission for HumanRights (KNCHR), UN agencies, national and internationalNGOs and community-based organisations.In early 2009, <strong>the</strong> Protection Cluster was transformedinto a national-level Protection WorkingGroup on Internal Displacement (PWGID)in order to expand its capacity for advocacy andto cover o<strong>the</strong>r interventions on a long term basis.The mandate of <strong>the</strong> PWGID included: advocacyand capacity-building of government institutionsthrough training sessions on <strong>the</strong> Guiding Principles;advocacy for <strong>the</strong> implementation of <strong>the</strong> GreatLakes <strong>IDP</strong> Protocol; participation in efforts towards<strong>the</strong> finalisation of <strong>the</strong> Kampala Convention,which existed <strong>the</strong>n in a draft form; and elaborationof a national policy on internal displacement.1.2. The Political andTechnical ProcessesTowards Drafting<strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> PolicyIn July 2009, <strong>the</strong> first stakeholders’ forum was heldat which <strong>the</strong> process of developing a policy on internaldisplacement for <strong>Kenya</strong> was initiated. Participantsat <strong>the</strong> forum included senior representativesfrom <strong>the</strong> Ministry of State for Special Programmes(MoSSP), from <strong>the</strong> National Steering Committeeon Peacebuilding and Conflict Management, <strong>the</strong>Provincial Administration and members of <strong>the</strong>PWGID. The outcome was a consensus on <strong>the</strong> needfor a national policy to address situations of internaldisplacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>. The PWGID was <strong>the</strong>ngiven <strong>the</strong> mandate to devise a strategy for drafting<strong>the</strong> policy in collaboration with MoJNCCA andMoSSP.The process of drafting <strong>the</strong> policy was taken upXII<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 1

Chapter 1: Introductionby <strong>the</strong> MoSSP and <strong>the</strong> Legal and Advocacy Sub-Working Group (LASWG), a <strong>the</strong>me group under<strong>the</strong> PWGID. Meetings were hosted at <strong>the</strong> ministryon a weekly basis with a technical advisor from<strong>the</strong> office of <strong>the</strong> Special Rapporteur on <strong>the</strong> HumanRights of <strong>IDP</strong>s (SR-<strong>IDP</strong>s) providing technicalsupport to <strong>the</strong> team. In March 2010, partnersreviewed a preliminary draft for <strong>the</strong> policy during<strong>the</strong> second stakeholders’ forum.From May to December 2010, <strong>the</strong> LASWG developedand disseminated a matrix auditing <strong>the</strong> legal,policy and institutional framework in relation to<strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s. The matrix indicated <strong>the</strong>weaknesses in <strong>the</strong> existing framework and justified<strong>the</strong> need for a concrete legal framework andfor implementing <strong>the</strong> draft Policy. In November2010, <strong>the</strong> team amended <strong>the</strong> draft policy to reflect<strong>the</strong> provisions of <strong>the</strong> newly-promulgated <strong>Kenya</strong>nConstitution so that it correlated with <strong>the</strong> frameworkfor devolution, human rights, values andprinciples of governance under <strong>the</strong> Constitution.Fur<strong>the</strong>r revisions were made in July 2012 to make<strong>the</strong> draft Policy compatible with <strong>the</strong> Land Act(2012), <strong>the</strong> Land Registration Act (2012) and <strong>the</strong>National Land Commission Act (2012). On 16thMarch 2011, <strong>the</strong> group submitted a draft cabinetmemo to MoSSP to accompany <strong>the</strong> policy for itspresentation to cabinet.To fur<strong>the</strong>r entrench its advocacy work, <strong>the</strong> PW-GID had engagements with o<strong>the</strong>r stakeholders like<strong>the</strong> Parliamentary Select Committee on <strong>the</strong> Resettlementof <strong>IDP</strong>s (PSC) and <strong>the</strong> Labour and SocialWelfare Committee (LWSC), which resulted in<strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong> Bill on internal displacement.The Prevention, Protection and Assistanceto Internally Displaced Persons Bill has alreadyreceived Presidential assent while <strong>the</strong> broaderpolicy document has been approved by <strong>the</strong> Cabinetand is awaiting presentation to Parliament fordebate. 41.3. Purpose and Objectivesof <strong>the</strong> StudyThe purpose of this study is to capture and analyse<strong>the</strong> advocacy and engagement process that wentinto <strong>the</strong> preparation of <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Policy and Bill in<strong>Kenya</strong>. By highlighting <strong>the</strong> challenges and lessonslearnt from <strong>the</strong> process, <strong>the</strong> outcome of this studyshould make a useful guide for discussions on advocacystrategies on forced migration policy at <strong>the</strong>national, regional and continental level.According to <strong>the</strong> Brookings Institution’s databaseon national laws and policies on internal displacement,only four countries in <strong>the</strong> Great Lakes regionhave developed an <strong>IDP</strong>-specific policy to deal withparticular protection needs. 5 The <strong>Kenya</strong>n experiencecould <strong>the</strong>refore inspire o<strong>the</strong>r countries within<strong>the</strong> region and beyond, especially as momentumbuilds up for <strong>the</strong> implementation of <strong>the</strong> GuidingPrinciples, <strong>the</strong> Kampala Convention and <strong>the</strong> GreatLakes <strong>IDP</strong> Protocol. Beyond its particular contexton internal displacement, lessons learnt from <strong>the</strong><strong>Kenya</strong>n process could also be useful for reflectingon policy development work in o<strong>the</strong>r sectors.1.4. The Partnership between<strong>the</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> Consortium of<strong>Kenya</strong> and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Danish</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong><strong>Council</strong> (Great LakesCivil Society Project)The Great Lakes Civil Society Project is a regionalprogramme implemented since January 2010 by<strong>the</strong> <strong>Danish</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong> in partnership withcivil society organisations in six countries of <strong>the</strong>Great Lakes region: Burundi, Central African Republic,Democratic Republic of Congo, <strong>Kenya</strong>,South Sudan and Uganda. The vision of <strong>the</strong> programmeis to build <strong>the</strong> capacity of civil society tohold governments accountable to <strong>the</strong>ir commitmentsto protect displaced persons by proposingrealistic policy solutions to conflict and displacement.The programme supports national civil societyorganisations in documenting and analysingspecific displacement and conflict issues, andtranslating <strong>the</strong>se analyses into practical advocacygoals at <strong>the</strong> local, national and regional levels. Theproject relies on existing legal and political frameworksfor <strong>the</strong> protection of refugees and <strong>IDP</strong>s and,where possible, encourages cross-border learningbetween civil society organisations and regionalinitiatives aimed at providing joint solutions to regionaldisplacement problems.The <strong>Refugee</strong> Consortium of <strong>Kenya</strong> (RCK) is anational Non-Governmental Organisation thatworks to promote and protect <strong>the</strong> rights and dignityof refugees and o<strong>the</strong>r forced migrants. RCK wasconstituted and registered in 1998 in response to<strong>the</strong> increasingly complex refugee situation in <strong>Kenya</strong>.RCK is distinct in <strong>the</strong> role it plays in promoting<strong>the</strong> welfare and rights of refugees and o<strong>the</strong>r forcedmigrants. It focuses on refugee and <strong>IDP</strong> issues usinga human rights and social justice approach asit advocates for <strong>the</strong>ir rights. In partnership withits networks locally, regionally and internationally,RCK has been able to deal with a wide rangeof issues in forced migration. These include legalreforms, policy development, civic education, researchand information dissemination, refugeeand <strong>IDP</strong> empowerment and capacity building.Since 2010, RCK in partnership with DRC GreatLakes has been engaged in <strong>IDP</strong> work under threestrategic objectives for <strong>the</strong> year 2012: i) Lobbyingfor <strong>the</strong> enactment of <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Policy with differentduty bearers; ii) Creating awareness on <strong>the</strong> rightsand protection needs of <strong>IDP</strong>s in <strong>Kenya</strong>; and iii)Documenting <strong>the</strong> advocacy and engagement processtowards an <strong>IDP</strong> policy framework in <strong>Kenya</strong>.1.5. Methodology of <strong>the</strong> Study1.5.1. Desk ReviewThis study was informed by a review of a numberof secondary sources of information in <strong>the</strong> formof publications, reports, minutes, concept papers,as well as relevant national, regional and internationalframeworks on <strong>IDP</strong>s. This information wasused to build <strong>the</strong> context on <strong>IDP</strong> protection, identifygaps in existing protection and advocacy initiatives,identify <strong>the</strong> key stakeholders in <strong>IDP</strong> work,and establish benchmarks for protection and advocacywork.1.5.2. Key Informant InterviewsThe study made use of purposive sampling, interviewingvarious respondents from organisationsor institutions that have taken an active part in <strong>the</strong>policy development process. These respondentsincluded state and non-state actors and representedinternational, national and field-based level actors.The interviews were mainly conducted usingsemi-structured questionnaires as well as informaldiscussions.In total, 22 stakeholders were interviewed. 13 wererepresentatives of state institutions comprisingof four international (mainly UN Agencies), sixnational (from relevant ministries, <strong>Kenya</strong> NationalCommission on Human Rights – KNCHR,and Parliament) and three field-based ProtectionWorking Group members (mainly from <strong>the</strong> ProvincialAdministration in Nakuru and Eldoret).Nine non-state actors were also interviewed: twointernational non-governmental organisations,four national actors and three members from <strong>the</strong><strong>IDP</strong> Network. Informal reflections were also undertakenwith members of <strong>the</strong> Eldoret field-basedProtection Working Group on 26 st July 2012.1.5.3. Internal RCK ReflectionWhile <strong>the</strong> consultants who conducted this studycarried out interviews with <strong>the</strong> relevant stakeholdersin an attempt to re-enact and re-examine<strong>the</strong> policy development process, <strong>the</strong>y also reliedon information accumulated by RCK from its ownadvocacy work. RCK has played a significant rolein <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong> policy framework oninternal displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>. Initial efforts inthis respect have included preliminary discussionswith actors around <strong>the</strong> prospect of developing an<strong>IDP</strong> Policy. After <strong>the</strong> post-election violence, <strong>the</strong>role of RCK became more concrete with <strong>the</strong> inceptionof <strong>the</strong> Protection Working Group on InternalDisplacement and of <strong>the</strong> legal and advocacy subgroupfor longer-term interventions such as policydevelopment, promotion of access to durable solutionsand ensuring a holistic approach to internaldisplacement in <strong>Kenya</strong>. The specific role of RCK2<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 3

Chapter 1: Introductioncannot be distinguished from <strong>the</strong> objectives andactivities of <strong>the</strong> advocacy sub-group of <strong>the</strong> PWGID.The strength of RCK as a partner in this sub-groupcould be ascribed to several factors, such as itsextensive experience in advocacy and policy development,most notably with <strong>the</strong> developmentof <strong>the</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong>s Act in 2006. Its programming forthat period had <strong>the</strong> technical and financial supportof <strong>the</strong> <strong>Danish</strong> <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong> Great Lakes CivilSociety Project and its approach and long standingrelationship with relevant stakeholders includingGovernment Ministries, civil society, UN bodiesand <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> communities was close and constantenough to influence and garner support for certaininitiatives and thus lend legitimacy to its actionsand <strong>the</strong> process at large. For instance, RCK soughtto address issues emerging at <strong>the</strong> local level suchas <strong>the</strong> flawed profiling exercise by <strong>the</strong> Government.RCK worked with partners to develop an abridgedversion of, and o<strong>the</strong>r IEC materials, on <strong>the</strong> draftpolicy. The IEC materials were disseminatedthrough its training sessions on peacebuilding andreconciliation with peace committee members inUasin Gishu County and o<strong>the</strong>r training sessions forstate and non-state actors on <strong>the</strong> rights of refugeesand o<strong>the</strong>r forced migrants. RCK also engaged withformal and informal channels to maintain knowledgeon <strong>the</strong> process and intervene where possiblewith this advocacy expertise. For instance, RCKbenefited from <strong>the</strong> Executive Director’s previousengagements with <strong>the</strong> Minister of State for SpecialProgrammes (MoSSP) in <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong>Sexual Offences Act. 6 These established relationshipsand facilitated <strong>the</strong> organisation of high levelmeetings at short notice, helped <strong>the</strong> sub-group accesstimely information such as <strong>the</strong> status of <strong>the</strong>draft policy within <strong>the</strong> MoSSP and made it easierfor RCK to mobilise <strong>the</strong> relevant ministry staff toparticipate in <strong>the</strong> key workshops and meetings relatedto advocacy around <strong>the</strong> draft <strong>IDP</strong> Policy.In <strong>the</strong> same spirit, <strong>the</strong> MoSSP recognised <strong>the</strong> roleof RCK in <strong>the</strong> process of developing <strong>the</strong> policyframework and subsequently invited RCK to contributeto critical technical meetings that pushed<strong>the</strong> policy forward at different stages. Key meetingsincluded <strong>the</strong> first committee meeting of <strong>the</strong>Parliamentary Select Committee on <strong>the</strong> Resettlementof <strong>IDP</strong>s in Naivasha in February 2011, and <strong>the</strong>workshop between <strong>the</strong> MoSSP and <strong>the</strong> Ministry ofLand to build consensus around <strong>the</strong> provisions of<strong>the</strong> draft <strong>IDP</strong> Policy for both ministries in order toresubmit it to Cabinet in August 2012. RCK staffalso followed parliamentary proceedings duringtwo of <strong>the</strong> three readings of <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Bill in parliament.They regularly prepared briefing notes andshared with <strong>the</strong> advocacy sub-group to keep <strong>the</strong>minformed of progress of both <strong>the</strong> Policy and <strong>the</strong>Bill.1.5.4. Theoretical and ConceptualFrameworkIn this study and report, “policy” will be understoodin a very broad sense to include generalpolicy, specific policy, laws, institutions and governmentpractice. Unless o<strong>the</strong>rwise specified,<strong>the</strong>refore, reference to a policy framework includesreference to <strong>the</strong> Constitution, legislation,institutional set up and practices, whe<strong>the</strong>r in writtenform or not, existing in a single document orscattered across numerous sources, and whe<strong>the</strong>rimplemented in an ad hoc manner or sustainedand guided by some objective work-plans. It alsoincludes failure by <strong>the</strong> Government to take particularaction or courses of action (omission).In analysing <strong>the</strong> role of CSOs, this study greatlyrelied on a five-stage policy development cyclewhich covers setting <strong>the</strong> agenda for policy development;formulating <strong>the</strong> policy; adopting <strong>the</strong> policy;implementing <strong>the</strong> policy; and evaluating <strong>the</strong>policy. 7 By using <strong>the</strong> cycle, this report systemicallyassesses and re-examines <strong>the</strong> policy developmentprocess for ease of reference and adaptability forapplication in o<strong>the</strong>r contexts.The analysis in this report greatly benefited from<strong>the</strong> approach outlined in <strong>the</strong> Brookings Institution’smanual for law and policymakers especiallyin assessing <strong>the</strong> standard of protection offeredthrough policy interventions. 8 While seeking to establishbest practices that could be utilised beyond<strong>the</strong> national level, this study remained consciousof <strong>the</strong> primary obligation on <strong>the</strong> State to provideprotection and humanitarian assistance to internallydisplaced persons within <strong>the</strong>ir jurisdiction. 9At <strong>the</strong> heart of policymaking lies consensus-building,which is achieved through a consultative andparticipatory approach. This study views participationin policymaking as a continuum, with actorstaking part in <strong>the</strong> process to different extentsdepending on <strong>the</strong> surrounding circumstances and<strong>the</strong>ir inherent capabilities or disadvantages. As acontinuum, participation in policy encompassesa wide range of scenarios which may include: exchangeof information; public consultation andengagement; shared decisions and shared jurisdiction.Based on this, different actors would necessarilyengage with <strong>the</strong> policy development processto varying extents. This continuum was used to assess<strong>the</strong> extent to which stakeholders participatedin <strong>the</strong> process of developing <strong>the</strong> policy framework.1.5.5. Shortcomings of <strong>the</strong>MethodologyThe study encountered some methodological challenges.First, <strong>the</strong>re were several advancementsmade on <strong>the</strong> part of <strong>the</strong> Government towards <strong>the</strong>policy which were not properly documented. Thestudy would have benefited from engaging withmore Government stakeholders as key informantsthat could have shed light on <strong>the</strong> internal dynamicsthat affected <strong>the</strong> policy development process.This was not done on two accounts: first, becauseGovernment actors were scattered across numerousministries, sometimes with uncoordinated approaches,and second because of time constraints.For instance, while <strong>the</strong> PSC and its membersplayed an important role in <strong>the</strong> policy developmentprocess, it was not clear what <strong>the</strong>ir exact motivationwas nor what criteria were used to identify<strong>the</strong> original members of <strong>the</strong> committee.Secondly, though <strong>the</strong> interviews with <strong>the</strong> respondentstargeted persons and institutions that hadbeen significantly involved in <strong>the</strong> policy developmentprocess, at <strong>the</strong> time of <strong>the</strong> study some of<strong>the</strong>se respondents had moved to work with o<strong>the</strong>rorganisations or in o<strong>the</strong>r sectors. This affected tosome extent <strong>the</strong> respondents’ understanding of<strong>the</strong> two processes.Thirdly, as some persons interviewed had beeninvolved in <strong>the</strong> process of developing <strong>the</strong> policyframework, <strong>the</strong>re was a great risk of bias in <strong>the</strong>irassessment of <strong>the</strong> process. The study, however,greatly benefited from <strong>the</strong>se persons who had <strong>the</strong>institutional memory of <strong>the</strong> process and remainkey proponents of <strong>the</strong> process.4<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 5

Chapter 2:Setting <strong>the</strong> SceneThe Great Lakes region is said to be home to overeight million internally displaced persons. 10 <strong>IDP</strong>sare persons or groups of persons who have beenforced or obliged to flee or to leave <strong>the</strong>ir homes orplaces of habitual residence, in particular as a resultof or in order to avoid <strong>the</strong> effects of armed conflict,situations of generalised violence, violationsof human rights, natural or human-made disasters,and development programmes and who have notcrossed an internationally-recognised state border.11 Internal displacement within <strong>the</strong> region hasbeen caused by conflict, disaster, violence, massivedevelopment projects and socio-economicinequalities leading to landlessness among o<strong>the</strong>rthings. This population is distributed across all <strong>the</strong>nations that fall within <strong>the</strong> region and represents asignificant segment of global statistics on internaldisplacement. 12<strong>Kenya</strong> has a long history of displacement with aclimax in <strong>the</strong> aftermath of <strong>the</strong> 2007/ 2008 postelectionviolence. This section discusses some of<strong>the</strong> causes of violence in <strong>Kenya</strong> as a way of providinga context for understanding advocacy work fora policy on internal displacement.2.1. Causes of Displacement in<strong>Kenya</strong>2.1.1. Colonial and Post-ColonialFactorsThe introduction of colonisation saw <strong>the</strong> forceddisplacement of African communities from <strong>the</strong>irancestral lands to make way for <strong>the</strong> white settlers.In <strong>Kenya</strong>, this was exemplified in evictions fromfertile lands in Rift-Valley and Central <strong>Kenya</strong> where<strong>the</strong> natives were reduced to squatter-labour forcefor colonial settlers. At <strong>the</strong> time of independence,it was expected that this adverse legacy of colonialland alienation processes would be corrected. 13However, <strong>the</strong> post-independence governmentwent ahead to preside over a land re-distributionprogramme that instead became a fur<strong>the</strong>r sourceof discord. Initial land allocations in favour of personswho had been labourers on <strong>the</strong> settler farmsincensed <strong>the</strong> pastoralist communities of <strong>the</strong> RiftValley and fuelled <strong>the</strong> sentiment of “outsider communities”which continues to persist to this day.The situation was compounded by a programme toempower communities through formation of landbuyingcompanies which saw large-scale land acquisitionby communities perceived as close to <strong>the</strong>centre of power. This historical context infuseditself with <strong>the</strong> political and ethnic relations of<strong>Kenya</strong>n society and has become a cause of periodicpopulation movements and displacement in<strong>Kenya</strong>. 142.1.2. Election-related ViolenceMassive internal displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> can betraced to <strong>the</strong> re-introduction of multi-party politicsin 1992 with political parties formed largelyalong ethnic lines becoming vehicles for championingredress for perceived communal injustices.This trend continued into <strong>the</strong> 1997 general elections,with violence registered in <strong>the</strong> Rift Valleyand Coast provinces leading to <strong>the</strong> displacementof 120,000 people. The victims were largely fromcommunities perceived as supporters of oppositionparties. In total, election-related violence priorto <strong>the</strong> 2007 general elections is said to have beenresponsible for <strong>the</strong> displacement of approximately350,000 persons. 15 Violence following <strong>the</strong> 2007general elections saw an escalated and unprecedentedlevel of displacement that affected 663,921people. 16 Areas affected by election-related dis-placement include mainly Molo, Njoro, Kuresoi,Eldoret, Burnt Forest, and Coastal region. 172.1.3. Border and ResourceDisputes Including CattleRustling and BanditryClosely associated with political conflict are borderdisputes arising from arbitrarily establishedadministrative boundaries and contested landrights. As administrative boundaries began to createethnic enclaves, minority communities within<strong>the</strong>se boundaries soon became <strong>the</strong> target of forcefulevictions. Areas such as Chesikaki in Mt. Elgon,Ol Moran in Laikipia West, Thangatha in Tigania,<strong>the</strong> Pokot/Turkana border, Riosiri in Rongo,Tembu in Sotik, Masurura in Transmara, Marsabit-Isioloand Tana River 18 have been particularlyproblematic in this regard. 19 Related to generaldisputes about resources is <strong>the</strong> evolution of cattlerustlingfrom a traditional practice to one of belligerenceand criminality fuelled by politics and <strong>the</strong>proliferation of small arms and light weapons. Pastoralistcommunities such as <strong>the</strong> Pokot, Turkana,Marakwet, Samburu, Tugen and Keiyo continue toendure incidences of displacement, death and lossof livestock over time 20 , as detailed in a 2003 studyon conflict in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>Kenya</strong> estimating <strong>the</strong> levelof displacement in <strong>the</strong> pastoralist areas of NorthFrontier Districts (NFDs) 21 in <strong>Kenya</strong> 22 at 164,457.2.1.4. Natural and Human MadeDisasters 23A historical profile from 1975-2004 indicatesthat <strong>Kenya</strong> has experienced multiple episodes ofdrought, landslides and floods in various parts of<strong>the</strong> country with far-reaching economic and socialconsequences. 24 <strong>Kenya</strong> experiences regular floodsin <strong>the</strong> areas of Kano, Nyakach, Rachuonyo, Migori,Budalangi, Kilifi, Kwale, <strong>the</strong> Tana River Basin, Garrissa,Wajir, Nairobi, Nakuru, Mombasa, Kisumu,Baringo, Elgeyo and Marakwet districts. 25 Landslidesand mudslides also occur mostly during <strong>the</strong>rainy season and are accelerated by flooding.2.1.5. Development Projects andDisplacement<strong>Kenya</strong>ns have also been displaced from <strong>the</strong>ir landsand homes on account of development projectsand environmental conservation efforts carriedout arbitrarily. A recent decision from <strong>the</strong> AfricanCommission on Human and Peoples’ Rights restored<strong>the</strong> land rights of <strong>the</strong> Endorois communitywho had been displaced from <strong>the</strong>ir ancestral landsto make way for a game reserve. 26 More recently,a taskforce recommended <strong>the</strong> eviction of personsdeemed to have encroached on <strong>the</strong> Mau Forestscomplex in a bid to conserve <strong>the</strong> country’s essentialwater towers. 27 As of September 2011, some6,500 families had been evicted from <strong>the</strong> complexwith a fur<strong>the</strong>r 23,500 projected for eviction once<strong>the</strong> next phase of restoration commences. 28 O<strong>the</strong>rprojects that may lead to displacement include<strong>the</strong> Lamu Port-Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Sudan-Ethiopia Transport(LAPSSET) project and <strong>the</strong> discovery of oil inTurkana. The LAPSSET project will comprise of aport, an international airport and an oil refinery inLamu along with a road and pipeline network cuttingacross <strong>Kenya</strong>, Ethiopia and Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Sudanand according to initial assessment by <strong>the</strong> governmentmay affect 6,000 families. 292.2. Towards a PolicyFrameworkFrom <strong>the</strong> very outset, it must be acknowledgedthat although before 2008 <strong>Kenya</strong> did not have asingle repository encompassing all its policies inrelation to internal displacement, such polices didexist. The policies existed as part of o<strong>the</strong>r laws, forinstance those relating to human rights, developmentplans, disaster response, compulsory acquisitionof land, armed conflict and laws on generaladministration. O<strong>the</strong>r policies existed not in writtenform but were employed through practice andmostly depended on <strong>the</strong> preferences and prioritiesof <strong>the</strong> government of <strong>the</strong> day. 30 What <strong>Kenya</strong> wasreally missing before <strong>the</strong> 2008 displacements wasa consistent and coordinated response to internaldisplacement. The Government did not expresslyrecognise <strong>the</strong> protection needs of <strong>IDP</strong>s, and inter-6<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 7

Chapter 2: Setting <strong>the</strong> Sceneventions were consequently majorly ad hoc andnot focused on <strong>IDP</strong>s as such.Even without a comprehensive law for <strong>the</strong> protectionof <strong>IDP</strong>s, <strong>the</strong> Government has on severaloccasions sought to investigate disruptive incidentsthat led to displacement. In this regard,<strong>the</strong> Government had previously established varioustemporary institutional mechanisms to conductenquiry into incidences of displacementand make recommendations. 31 Fur<strong>the</strong>r, following<strong>the</strong> displacements triggered by <strong>the</strong> violence in2007/2008, it could be seen that <strong>the</strong> Governmenthad some basic mechanism for responding to internaldisplacement, or ra<strong>the</strong>r, to disasters. At <strong>the</strong>onset of <strong>the</strong> crisis, <strong>the</strong> Ministry of State for ProvincialAdministration and Internal Security coordinatedinterventions through <strong>the</strong> Disaster andEmergency Co-ordination Department. Later, <strong>the</strong>MoSSP established <strong>the</strong> Mitigations and ResettlementsDepartment to assist in resettling and restoringlivelihoods for <strong>IDP</strong>s after being made <strong>the</strong>focal point for coordinating interventions. TheMoSSP also had <strong>the</strong> Humanitarian Fund for Mitigationof Effects and Resettlement of Victims of<strong>the</strong> 2007 post-election violence. 32The move towards a comprehensive and cohesiveframework on internal displacement was <strong>the</strong>reforea reactionary phenomenon brought about by<strong>the</strong> level of prominence afforded to internal displacementfollowing <strong>the</strong> post-election violencein 2007/2008. The unsatisfactory nature of responsesby <strong>the</strong> Government (poor coordination,short-term planning, failure to allocate sufficientresources and poor profiling) and <strong>the</strong> uncoordinatedway in which various CSOs responded to internaldisplacement following <strong>the</strong> violence servedto highlight <strong>the</strong> need for a framework to act as aplatform for collaboration and coordination.While <strong>the</strong>re had been earlier attempts at advocacyon internal displacement, efforts intensified in2007 33 when <strong>the</strong> United Nations Office CoordinatingHumanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) 34 and <strong>the</strong> InternalDisplacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC)co-hosted <strong>the</strong> first capacity-building workshop on<strong>the</strong> Guiding Principles on <strong>IDP</strong>s for non-state actorsworking on <strong>IDP</strong> issues in Nairobi. The workshopled to <strong>the</strong> formation of a Task Force on <strong>IDP</strong>scomprised of all interested CSOs organised on arotational basis. It drew up a strategy to push for<strong>the</strong> development of a legal and policy frameworkon internal displacement, highlighted <strong>the</strong> needfor durable solutions, including <strong>the</strong> developmentof pilot projects for <strong>the</strong> resettlement of <strong>IDP</strong>s, andsought to establish a mechanism for dialogue andadvocacy work in cooperation with o<strong>the</strong>r actors. 35From 23rd to 25th April 2007, <strong>the</strong> International<strong>Refugee</strong> Rights Initiative (IRRI), IDMC and <strong>the</strong>Norwegian <strong>Refugee</strong> <strong>Council</strong> (NRC) co-organiseda regional workshop at <strong>the</strong> Silver Springs Hotelin Nairobi to encourage <strong>the</strong> adoption and implementationof protection mechanisms for <strong>IDP</strong>s.On <strong>the</strong> basis of this event, national stakeholderswere expected to host a follow-up conference witha view to streng<strong>the</strong>ning intervention strategies as<strong>the</strong> general elections approached. Additionally,<strong>the</strong> workshop was supposed to spearhead legaland policy actions while advocating for durablesolutions for <strong>IDP</strong>s in <strong>Kenya</strong>. Between August andOctober 2007, <strong>the</strong> Task Force undertook preparatorywork for <strong>the</strong> conference. Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong>conference had to be moved to February 2008 as<strong>the</strong> election period appeared not to provide a conduciveenvironment to hold it in November 2007.The conference did not take place in February asplanned because of <strong>the</strong> violence that erupted after<strong>the</strong> 2007 elections. The agenda items of <strong>the</strong> proposedworkshop were finally realised during <strong>the</strong>stakeholders’ forum organised in July 2009 to discussdurable solutions and <strong>the</strong> establishment of apolicy framework for <strong>IDP</strong>s.2.2.1. Development of anOverarching PolicyFrameworkAlthough <strong>the</strong> need for a policy on internal displacementhad been mooted in 2007, it properly beganin 2009 with a stakeholders’ forum in Nairobi heldon 30 st and 31 st July 2009. 36 The specific objectivesof <strong>the</strong> forum included to reflect on <strong>the</strong> gains madeand challenges faced in <strong>the</strong> protection of and pro-vision of assistance to <strong>IDP</strong>s after <strong>the</strong> post-electionviolence; to analyse <strong>the</strong> situation of <strong>IDP</strong>s displacedby o<strong>the</strong>r factors o<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> post-election violence;to review <strong>the</strong> existing and anticipated policy,legal and institutional frameworks at <strong>the</strong> nationaland international levels; to get <strong>the</strong> voices of <strong>IDP</strong>sand streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>ir involvement in all decisionmakingprocesses; to develop a framework forbuilding <strong>the</strong> capacity of stakeholders and to profile<strong>IDP</strong>s; and to develop strategies for advocacy andcommon interventions. 37This forum was followed by a National Stakeholders’Review Forum held in Nairobi on 14 th March2012 and during which a preliminary draft outlining<strong>the</strong> key provisions of an <strong>IDP</strong> policy was developedby <strong>the</strong> LASWG and presented to partners forreview. Deliberations from this forum were usedto improve <strong>the</strong> draft, <strong>the</strong> content of which was finalisedin April 2010. 38 Following <strong>the</strong> agreementon <strong>the</strong> general outline and content of <strong>the</strong> policy,<strong>the</strong> LASWG developed in May 2010 an advocacystrategy for <strong>the</strong> draft policy to run from June toDecember 2010. From May to December 2010,<strong>the</strong> Sub-Working Group audited <strong>the</strong> existing legal,policy and institutional frameworks with a viewto informing <strong>the</strong> implementation of <strong>the</strong> proposedpolicy. A detailed matrix was developed and disseminatedindicating <strong>the</strong> weaknesses in <strong>the</strong> existinglegal architecture and justifying <strong>the</strong> need for aconcrete legal framework to foster <strong>the</strong> implementationof <strong>the</strong> draft policy. 39In November 2010, <strong>the</strong> LASWG revised <strong>the</strong> draftpolicy to bring it in line with <strong>the</strong> newly-promulgatedConstitution of <strong>Kenya</strong>. 40 Following <strong>the</strong>serevisions, a draft cabinet memo was prepared andpresented to <strong>the</strong> MoSSP on 16th March 2011. Thiswas later presented to <strong>the</strong> relevant Cabinet subcommittee.41 Later, on 18th July 2012, <strong>the</strong> policywas revised to align it with developments in <strong>the</strong>land sector, in particular with <strong>the</strong> provisions of <strong>the</strong>Land Act, <strong>the</strong> Land Registration Act and <strong>the</strong> NationalLand Commission Act with respect to <strong>the</strong>protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s in <strong>the</strong> context of landlessness.2.2.2. Development of aLegislative FrameworkA legislative instrument forms part of a broaderpolicy context and seeks to give effect to variousaspects of <strong>the</strong> policy by giving <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> force of<strong>the</strong> law. Similar to <strong>the</strong> need for broader policy oninternal displacement, <strong>the</strong> need for legislation oninternal displacement was identified during <strong>the</strong>workshops held in March and April 2007. However,<strong>the</strong> real momentum came when Parliament established<strong>the</strong> Parliamentary Select Committee on<strong>the</strong> Resettlement of <strong>IDP</strong>s (PSC) on 17 th November2010 in response to what it considered an inadequategovernment response to internal displacement.The mandate of <strong>the</strong> PSC included examining<strong>the</strong> policies and laws governing all forms of forceddisplacement and coming up with a draft Bill onforced displacement. 42 Having conducted numerouspublic hearings with multiple stakeholders,<strong>the</strong> PSC recommended <strong>the</strong> need for a legislationto ensure that government action on internal displacementwould be well coordinated, adequatelyresourced and in line with its constitutional andinternational obligations. 43This recommendation provided an avenue for <strong>the</strong>PSC and <strong>the</strong> PWGID to work toge<strong>the</strong>r given <strong>the</strong>progress made so far by <strong>the</strong> PWGID in relation to<strong>the</strong> draft <strong>IDP</strong> policy.2.2.3. Synchronising <strong>the</strong> Policyand Legislative ProcessesWhile <strong>the</strong> entry of <strong>the</strong> PSC into <strong>the</strong> discourse onestablishing a framework for <strong>the</strong> protection of<strong>IDP</strong>s was timely, it brought with it some structuralchallenges. Whereas <strong>the</strong> PWGID had concentratedits efforts on developing <strong>the</strong> broader policy andhad worked closely with <strong>the</strong> executive arm of <strong>the</strong>government (MoSSP and MoJNCCA), <strong>the</strong> PSC’smandate on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand was parliamentary.In addition, its initiation was not related to <strong>the</strong>broader policy development process. The processof cooperation with <strong>the</strong> PSC <strong>the</strong>refore startedwith attempts to reconcile and merge <strong>the</strong> progressmade so far by <strong>the</strong> PWGID on <strong>the</strong> policy with <strong>the</strong>mandate, interests and strategies of <strong>the</strong> PSC.8<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 9

Chapter 2: Setting <strong>the</strong> SceneThis process started with a strategic planningworkshop organised by <strong>the</strong> PSC in which membersof <strong>the</strong> PWGID advocacy sub-group outlinedkey issues regarding internal displacement andintroduced <strong>the</strong> draft <strong>IDP</strong> policy to <strong>the</strong> PSC. TheBill prepared by <strong>the</strong> PSC was presented during thisworkshop and it was agreed that it should be revisedin accordance with <strong>the</strong> contributions made at<strong>the</strong> workshop, <strong>the</strong> principles related to protectionduring internal displacement and o<strong>the</strong>r legislativedrafting requirements.This initial engagement was followed by a workshoporganised by RCK between <strong>the</strong> PWGID and<strong>the</strong> PSC, which fur<strong>the</strong>r discussed <strong>the</strong> internationalstandards on <strong>IDP</strong> protection, <strong>the</strong> extent to which<strong>the</strong>y were incorporated into <strong>the</strong> draft <strong>IDP</strong> policyand <strong>the</strong> probable role for an <strong>IDP</strong> Bill. This secondworkshop took place on 30 st September and 1 st October2011. RCK, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> PWGID, convenedthis forum to review <strong>the</strong> initial draft of <strong>the</strong><strong>IDP</strong> Bill and to work towards conclusion of <strong>the</strong> process.The forum appointed <strong>the</strong> PWGID advocacysub-group to review <strong>the</strong> draft Bill and submit it fora final review and validation in December 2011,just before <strong>the</strong> expiry of <strong>the</strong> term of <strong>the</strong> PSC. 44 Thecomposition of <strong>the</strong> PWGID, and <strong>the</strong> advocacy subgroupin particular, benefited from having a longstandingstructure, as <strong>the</strong> PSC were persuaded bythis arrangement when it came to committing <strong>the</strong>review of <strong>the</strong> draft with a reliable and proven arrangement.The second forum was attended by <strong>the</strong> Minister ofState for Special Programmes, who expressed hersupport for <strong>the</strong> draft Bill. The Minister’s participationwas also important as it provided an opportunityto lobby her to hasten <strong>the</strong> finalisation of <strong>the</strong>policy that had stalled for some time. The PWGIDused this forum strategically to lobby for <strong>the</strong> Ministry’ssupport of <strong>the</strong> draft Bill, especially because<strong>the</strong> Bill would be tabled in Parliament as a “privatemembers’ bill”. The Minister’s commitment to supporting<strong>the</strong> Bill was instrumental at <strong>the</strong> later stagesof debate on <strong>the</strong> Bill, as <strong>the</strong> Ministry moved a crucialamendment that provided for <strong>the</strong> proposed<strong>IDP</strong> humanitarian fund in <strong>the</strong> Bill to receive fundingfrom <strong>the</strong> Government’s consolidated fund.These forums marked important stages in <strong>the</strong>policy development process, especially where <strong>the</strong>realisation of <strong>the</strong> Bill was concerned and in <strong>the</strong>sensitisation process of <strong>the</strong> PSC to understand,and consequently support, <strong>the</strong> proposed policyframework for internal displacement. The PW-GID submitted <strong>the</strong> final version of <strong>the</strong> Bill to <strong>the</strong>PSC during <strong>the</strong> December workshop and committedto work with <strong>the</strong> MoSSP and o<strong>the</strong>r Governmentstakeholders to move <strong>the</strong> process forward. 45The final report of <strong>the</strong> PSC was unanimouslyadopted in Parliament on 2 nd August 2012. 46 Thereport had a number of recommendations includingone that called for:The Government [to] establish a legal frameworkon internal displacement through formulation of[a] policy and enactment of <strong>the</strong> draft bill on prevention,protection and assistance of <strong>IDP</strong>s. This legalframework should take into account <strong>the</strong> UN GuidingPrinciples, <strong>the</strong> AU Convention (Kampala Protocol)and Great Lakes Protocol on Protection andAssistance of <strong>IDP</strong>s. 47With <strong>the</strong> adoption of <strong>the</strong> Committee’s report, <strong>the</strong>chair of <strong>the</strong> PSC, Hon. Ekwe Ethuro, seized <strong>the</strong>opportunity to build momentum for <strong>the</strong> enactmentof <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Bill. The Bill was published on 24 thApril 2012, and was presented to Parliament for itsfirst reading on 13 th June 2012. After its first readingin Parliament, <strong>the</strong> Bill was committed to <strong>the</strong>Parliamentary Labour and Social Welfare Committee(LWSC) for review. The PWGID advocacysub-group organised a forum in Mombasa in July2012 to sensitise members of this committee on<strong>the</strong> protection needs of <strong>IDP</strong>s and took <strong>the</strong> opportunityto lobby for its adoption in Parliament. TheBill underwent three readings in Parliament beforebeing passed. It is useful to note <strong>the</strong> key deliberationsthat occurred during <strong>the</strong> readings as <strong>the</strong>seinformed <strong>the</strong> state of <strong>the</strong> Bill as it was passed and<strong>the</strong> concessions and challenges for stakeholders inpolicy making.The second reading took place on 19 th September2012 and showed broad based support for <strong>the</strong> Bill,albeit with significant misconception and misun-derstandings of <strong>IDP</strong> issues, and despite <strong>the</strong> factthat a lot of <strong>the</strong> sensitisation had been conductedby <strong>the</strong> PWGID, specifically targeting <strong>the</strong> LSWC.Examples include <strong>the</strong> introduction of integrated<strong>IDP</strong>s as a separate category of <strong>IDP</strong>s requiring definitionand references to <strong>IDP</strong> protection as refugeeprotection. It was promising to note, however, thatMPs recognised <strong>the</strong> Bill as addressing all forms ofdisplacement including historical evictions andpraised it for acknowledging <strong>the</strong> forthcoming devolvedsystem of government.The third reading took place on 4 th October 2012and brought about <strong>the</strong> most amendments bothfrom Parliament and indirectly from stakeholdersthrough submission of proposed amendmentsto Hon. Ekwe Ethuro. Most notably, Hon. Es<strong>the</strong>rMurugi proposed that <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Fund be fundedfrom <strong>the</strong> Exchequer (Government budgetary allocation).Hon. Millie Odhiambo also lobbied hard toensure that <strong>IDP</strong>s and UN agencies remain within<strong>the</strong> National Consultative Coordination Committee.The clause on armed groups being required toadhere to <strong>the</strong> provisions of <strong>the</strong> Act was deleted forfear that such observance would afford legal statusor recognition of armed groups despite <strong>the</strong> provisionexpressly providing o<strong>the</strong>rwise.2.2.4. Taking Stock of <strong>the</strong> ProcessAlthough <strong>the</strong> process of establishing a policyframework for <strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s in <strong>Kenya</strong> isyet to be fully completed, <strong>the</strong> advocacy efforts thatwent into its development have recorded some remarkableachievements. The process of passing<strong>the</strong> legislation has moved fast despite a crowdedlegislative calendar that was preoccupied with<strong>the</strong> implementation of <strong>the</strong> Constitution throughscheduled legislations. 48 The initiative managed tohighlight <strong>the</strong> protection needs of <strong>IDP</strong>s and helpedconstruct it as a national problem that transcendedethnic and political affiliations. By successfullydeveloping this narrative, <strong>the</strong> advocacy work hasset <strong>the</strong> pace for objective discussions.Support for <strong>the</strong> Bill on internal displacement hasbrought about a renewed push for <strong>the</strong> adoptionof <strong>the</strong> draft <strong>IDP</strong> Policy within <strong>the</strong> MoSSP. In <strong>the</strong>course of developing <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Bill, <strong>the</strong> PSC made effortsto hold <strong>the</strong> MoSSP accountable for <strong>the</strong> statusof <strong>the</strong> draft <strong>IDP</strong> Policy and <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Landsto be involved in <strong>the</strong> process by summoning <strong>the</strong>Ministers during its public hearings.Both <strong>the</strong> draft Bill and draft Policy on internaldisplacement have incorporated internationalstandards on <strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s. 49 The policiesadopt a human-rights based approach, establish acoordination framework and emphasise <strong>the</strong> primaryresponsibility of <strong>the</strong> government to protect<strong>IDP</strong>s while spelling out <strong>the</strong> role of non-state actors.In addition, both <strong>the</strong> broader Policy and <strong>the</strong>Bill deal with displacement through all its phasesfrom prevention to <strong>the</strong> achievement of durable solutionsand respond to all forms of displacementsirrespective of <strong>the</strong>ir cause.The collaboration and networking amongst <strong>the</strong>members of <strong>the</strong> PWGID has enriched <strong>the</strong> processand provided a blend of expertise. Of significancehas been <strong>the</strong> involvement of <strong>the</strong> legal expert from<strong>the</strong> Office of <strong>the</strong> UN Special Rapporteur on <strong>IDP</strong>s,who helped in drafting both <strong>the</strong> Policy and <strong>the</strong> Bill.The legal expert critically analysed <strong>the</strong> internationalframeworks on internal displacement sothat <strong>the</strong> proposed drafts were attuned to any discrepancieswith <strong>the</strong> UN Guiding Principles or <strong>the</strong>Great Lakes Protocol, as well as existing provisionswithin national legislation, <strong>the</strong> most notable onebeing <strong>the</strong> Constitution of 2010. The members of<strong>the</strong> PWGID advocacy sub-group remained steadfastin <strong>the</strong>ir advocacy work and kept <strong>the</strong> agendawithin <strong>the</strong> mandate of <strong>the</strong>ir protection work.The participation of <strong>the</strong> Government in drafting<strong>the</strong> policy helped elevate <strong>the</strong> status of <strong>the</strong> advocacywork by promising official support. Representativesfrom <strong>the</strong> Ministry of State for SpecialProgrammes and <strong>the</strong> Ministry of Justice attendedmost of <strong>the</strong> meetings where <strong>the</strong> policy was beingdeveloped.The stakeholders carried out activities aimed atdisseminating <strong>the</strong> content of <strong>the</strong> policy and legislationthrough various forums. This was donethrough <strong>the</strong> production and dissemination ofbrochures, documentaries, policy briefs and posi-10<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 11

Chapter 2: Setting <strong>the</strong> Scenetion papers, periodical reports and Information,Educational and Communication (IEC) materials.O<strong>the</strong>rsstrategies entailed updates and sharing of informationthrough monthly PWGID meetings. Pressstatements, TV and radio talk show programmeswere also used to create public awareness on <strong>the</strong>engagements. 50Chapter 3:The Role of <strong>the</strong> PWGID:Added Value of a NationalCoordination MechanismFinally, although <strong>the</strong> policy on internal displacementis based on international standards, it alsoenhances and elevates <strong>the</strong> instruments in <strong>Kenya</strong>.For instance, <strong>the</strong> enactment of <strong>the</strong> Bill on internaldisplacement gives <strong>the</strong> standards full force of law.The policy itself is specific on <strong>the</strong> obligation imposedon <strong>the</strong> State as <strong>the</strong> primary protector witho<strong>the</strong>r actors playing only a supporting role. Moreover,<strong>the</strong> policies anchor protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s on aright-based platform <strong>the</strong>reby confirming that <strong>the</strong>protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s is not a mere political venturebut a human rights issue.PWGID workshop with PSC on resettlement of <strong>IDP</strong>s, at Pangoni Beach Resort from 4th - 6th Dec. 2011In <strong>Kenya</strong>, <strong>the</strong> PWGID provided a vehicle for <strong>the</strong>coordination of advocacy efforts and collectiveapproaches on internal displacement. It acted asa focal point for discussions, information sharing,planning and review of strategies by various stakeholders51 involved in advocacy and o<strong>the</strong>r interventionson internal displacement.3.1. Institutional Responses to<strong>the</strong> Post-Election Violencein 2007/2008The aftermath of <strong>the</strong> 2007/2008 post-election violenceand <strong>the</strong> humanitarian crisis that followed,exposed <strong>the</strong> ineffectiveness of existing governmentstructures to respond to internal displacement.It triggered action towards establishing alegal and institutional framework focused exclusivelyon internal displacement.Organisations interviewed for this study indicatedthat <strong>the</strong>y have responded in various ways to issuessurrounding internal displacement within <strong>the</strong>irinstitutional mandates, interests and strategies.Their key strategies include advocacy for durablesolutions, work on <strong>the</strong> development of a policyframework on <strong>the</strong> protection of and provision ofassistance to <strong>IDP</strong>s, coordination of humanitarianresponses, research and documentation of <strong>IDP</strong> issues,and provision of technical and financial supportfor activities related to <strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s.The coordination of most of <strong>the</strong>se interventionswas done through <strong>the</strong> “Early Recovery CoordinationMechanism” which provided a forum for partnershipand collaboration in a multifaceted yet interconnectedapproach in various areas.3.2. Collective Responseswithin <strong>the</strong> PWGIDThe PWGID was established on 3 rd February 2009to replace <strong>the</strong> national <strong>IDP</strong> Protection Cluster(PC). 52 The PC was spearheaded by <strong>the</strong> UNHCRin January 2008 and brought toge<strong>the</strong>r more than30 agencies from <strong>the</strong> UN, KNCHR, national andinternational NGOs and <strong>the</strong> <strong>IDP</strong> Network. 53The mandate of <strong>the</strong> PWGID 54 was to enhance<strong>the</strong> capacity of actors to address <strong>the</strong> protectionneeds of <strong>IDP</strong>s throughout <strong>Kenya</strong> through trainingon <strong>the</strong> Guiding Principles, advocating for <strong>the</strong>implementation of <strong>the</strong> Great Lakes <strong>IDP</strong> Protocol,finalising <strong>the</strong> ratification process of <strong>the</strong> KampalaConvention, developing a national legal and policyframework for <strong>the</strong> protection of <strong>IDP</strong>s in <strong>Kenya</strong>,establishing a monitoring mechanism to ensurecompliance with regional and international commitments,and identifying <strong>the</strong> protection needsof <strong>IDP</strong>s by highlighting <strong>the</strong> human rights context,gaps and specific government obligations. 55On 3 rd February 2009, <strong>the</strong> Legal Aid Sub-WorkingGroup was formed to provide technical support toand advise <strong>the</strong> PWGID around a number of issues,which included <strong>the</strong> development of policies andlegislation on internal displacement, <strong>the</strong> provisionof legal aid to <strong>IDP</strong>s during <strong>the</strong>ir engagementswith judicial and quasi-judicial processes such asTribunals, <strong>the</strong> Truth, Justice and ReconciliationCommission (TJRC), <strong>the</strong> design of schemes forreparation, pursuit for durable solutions, and enforcementof <strong>the</strong> obligation of Government to protect<strong>IDP</strong>s. Following <strong>the</strong> finalisation of <strong>the</strong> draftingprocess for <strong>the</strong> policy in April 2010, <strong>the</strong> LASWG12<strong>Behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Scenes</strong> – Lessons Learnt from Developing a National Policy Framework on Internal Displacement in <strong>Kenya</strong> 13