Language Awareness Noun, verb, or adjective? L2 learners ...

Language Awareness Noun, verb, or adjective? L2 learners ...

Language Awareness Noun, verb, or adjective? L2 learners ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

This article was downloaded by: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz]On: 13 July 2010Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 918976463]Publisher RoutledgeInf<strong>or</strong>ma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: M<strong>or</strong>timer House, 37-41 M<strong>or</strong>timer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK<strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong>Publication details, including instructions f<strong>or</strong> auth<strong>or</strong>s and subscription inf<strong>or</strong>mation:http://www.inf<strong>or</strong>maw<strong>or</strong>ld.com/smpp/title~content=t794297825<strong>Noun</strong>, <strong>verb</strong>, <strong>or</strong> <strong>adjective</strong>? <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong>' sensitivity to cues to w<strong>or</strong>d classEve Zyzik aa<strong>Language</strong> Program, University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz, Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, United StatesTo cite this Article Zyzik, Eve(2009) '<strong>Noun</strong>, <strong>verb</strong>, <strong>or</strong> <strong>adjective</strong>? <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong>' sensitivity to cues to w<strong>or</strong>d class', <strong>Language</strong><strong>Awareness</strong>, 18: 2, 147 — 164To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09658410902855847URL: http://dx.doi.<strong>or</strong>g/10.1080/09658410902855847PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLEFull terms and conditions of use: http://www.inf<strong>or</strong>maw<strong>or</strong>ld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdfThis article may be used f<strong>or</strong> research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial <strong>or</strong>systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan <strong>or</strong> sub-licensing, systematic supply <strong>or</strong>distribution in any f<strong>or</strong>m to anyone is expressly f<strong>or</strong>bidden.The publisher does not give any warranty express <strong>or</strong> implied <strong>or</strong> make any representation that the contentswill be complete <strong>or</strong> accurate <strong>or</strong> up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, f<strong>or</strong>mulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable f<strong>or</strong> any loss,actions, claims, proceedings, demand <strong>or</strong> costs <strong>or</strong> damages whatsoever <strong>or</strong> howsoever caused arising directly<strong>or</strong> indirectly in connection with <strong>or</strong> arising out of the use of this material.

150 E. Zyzikintrospective data were gathered. To approach this question, it is useful to examine the cuesavailable to <strong>learners</strong> when distinguishing w<strong>or</strong>d classes.Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010Cues to w<strong>or</strong>d class assignmentThe categ<strong>or</strong>isation of w<strong>or</strong>ds into classes, such as noun, <strong>verb</strong>, and <strong>adjective</strong> is a complexprocess that involves parsing the input f<strong>or</strong> m<strong>or</strong>phological, syntactic, and semanticcues. 2 M<strong>or</strong>phological cues encompass both derivations and inflections; while derivationalm<strong>or</strong>phemes can change the lexical categ<strong>or</strong>y of a base w<strong>or</strong>d (e.g. indicate – indication), inflectionalm<strong>or</strong>phemes serve to identify w<strong>or</strong>ds as members of a particular class (e.g. Englishw<strong>or</strong>ds that are inflected with –ed and −s are necessarily <strong>verb</strong>s). Syntactic cues are also ofcritical imp<strong>or</strong>tance to w<strong>or</strong>d class assignment; these are the co-occurrence properties of aw<strong>or</strong>d with adjacent lexical items, that is, the distribution of certain classes of w<strong>or</strong>ds. F<strong>or</strong>example, English <strong>verb</strong>s are often preceded by do-f<strong>or</strong>ms; this is one of the syntactic cuesthat distinguishes them from <strong>adjective</strong>s, which are typically preceded by a f<strong>or</strong>m of be <strong>or</strong>get (cf. Braine, 1987; Maratsos, 1988). Syntactic cues of this type are viewed as essentialto the categ<strong>or</strong>isation of w<strong>or</strong>ds into classes, as demonstrated by connectionist models(Finch & Chater, 1992, 1994), statistical netw<strong>or</strong>ks of large language c<strong>or</strong>p<strong>or</strong>a (Redington& Chater, 1998), artificial language-learning studies (Mintz, 2002), and studies of childdirectedspeech (Cartwright & Brent, 1997; Mintz, 2003; Mintz et al., 2002; Redington,Chater, & Finch, 1998). Finally, w<strong>or</strong>d meaning may also be an indicat<strong>or</strong> of w<strong>or</strong>d class.F<strong>or</strong> <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong>, using semantic inf<strong>or</strong>mation in assigning w<strong>or</strong>d class means finding theL1 equivalent. F<strong>or</strong> example, upon learning the w<strong>or</strong>d libro in Spanish, an English-speakinglearner can simply rely on the L1 equivalent (‘book’) and c<strong>or</strong>rectly classify the new w<strong>or</strong>d asa noun. In this sense, positive transfer is expected to occur in the semantic domain becauseL1–<strong>L2</strong> exact equivalents will belong to the same w<strong>or</strong>d class (Sunderman & Kroll, 2006).Viewed in this way, w<strong>or</strong>d class is not strictly a problem of vocabulary learning but ratherone of categ<strong>or</strong>isation; the learner must attend to multiple linguistic cues (m<strong>or</strong>phological,syntactic, and semantic) in <strong>or</strong>der to arrive at the c<strong>or</strong>rect classification of lexical itemsin the input. In <strong>or</strong>der to exploit syntactic cues to w<strong>or</strong>d class, the learner must alreadyknow something about the distributional regularities of the language. Crucially, this entireprocess is understood to be largely implicit. Ellis (2007, p. 21) defines implicit learning as the‘acquisition of knowledge about the underlying structure of a complex stimulus environmentby a process that takes place naturally, simply, and without conscious operations’. The factthat adult native speakers are often unable to <strong>verb</strong>alise their knowledge of w<strong>or</strong>d classesis strong evidence f<strong>or</strong> the implicit mode of learning. The ability to label a w<strong>or</strong>d c<strong>or</strong>rectlyas a noun <strong>or</strong> a <strong>verb</strong> should not be confused with the tacit knowledge of using w<strong>or</strong>dsc<strong>or</strong>rectly acc<strong>or</strong>ding to the grammatical properties of their class. Although <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong> maydisplay m<strong>or</strong>e robust explicit knowledge of w<strong>or</strong>d classes, categ<strong>or</strong>ising newly learned w<strong>or</strong>dsis still a matter of abstracting the regularities from the <strong>L2</strong> input and/<strong>or</strong> deriving w<strong>or</strong>d classinf<strong>or</strong>mation from the L1 (i.e. positive transfer). Acc<strong>or</strong>dingly, of interest to the current studyare the cues that <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong> attend to when faced with a w<strong>or</strong>d class contrast, that is whetherthey notice the m<strong>or</strong>phological and/<strong>or</strong> syntactic cues in the input, whether they rely onL1 equivalents, <strong>or</strong> whether they make use of other mechanisms such as perceived w<strong>or</strong>dfrequency and familiarity with particular f<strong>or</strong>ms.Present studyIn the present study, concurrent and retrospective think-aloud data were gathered to examinethe following research questions:

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong> 151(1) What kind of cues do <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong> attend to when choosing between f<strong>or</strong>ms that belongto different w<strong>or</strong>d classes? Are certain cues used m<strong>or</strong>e frequently than others?(2) What is the relationship between the use of certain cues and success in choosingbetween semantically related f<strong>or</strong>ms?(3) Do w<strong>or</strong>d class err<strong>or</strong>s in the receptive mode stem primarily from faulty classification oflexical items <strong>or</strong> incomplete knowledge of syntactic regularities?Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010MethodParticipantsThe <strong>learners</strong> (n = 35; 29 females, six males) were beginners enrolled in a third-semesterSpanish course at a large, public university in the United States. They ranged in age from18 to 29 years, with the average age being 19.7. All indicated English as their nativelanguage on a background questionnaire, but three <strong>learners</strong> also spoke another languageat home (Punjabi, Gujurati, and Polish). With the exception of four participants, all hadstudied Spanish in high school (3.2 years on average). As f<strong>or</strong> exposure to other languagesin addition to Spanish, a small number had studied French (5), Tagalog (1), Mandarin (1),and Japanese (1).MaterialsThe task used was a sh<strong>or</strong>ter version of the f<strong>or</strong>ced-choice task (FCT) described in Zyzik andAzevedo (2009). It included 16 experimental sentences and 16 fillers. The fillers consistedof two types of items: (1) those in which the two f<strong>or</strong>ms did not radically differ fromone another (e.g. mood contrasts, such as escuches/escuchas ‘listen’), and (2) semanticcontrasts, such as saber/conocer ‘to know’ and ser/estar ‘to be’). The filler items werebalanced f<strong>or</strong> response options: items in which both f<strong>or</strong>ms were possible, one f<strong>or</strong>m wasc<strong>or</strong>rect, <strong>or</strong> neither was right. The 16 experimental sentences were those items that yieldedthe lowest mean sc<strong>or</strong>es in Zyzik and Azevedo (2009). These sentences are provided inAppendix 1.Think-aloud protocolsVerbal rep<strong>or</strong>ts (e.g. think-aloud protocols and stimulated recall) have been established asan imp<strong>or</strong>tant data collection method in SLA research because they have the potential f<strong>or</strong>capturing <strong>learners</strong>’ cognitive processes as they process language. Many strands of SLAresearch have utilised some f<strong>or</strong>m of <strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>ts, including studies of lexical inferencing(Cooper, 1999; Nassaji, 2003; Parabakht & Wesche, 1999), attention and awarenessstudies (Leow, 2001), and research on interactional feedback (Egi, 2004; Mackey, Gass,& McDonough, 2000; Nabei & Swain, 2002; Philp, 2003). Despite their applicability tovarious areas of SLA research, there have been some concerns about the internal validity of<strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>ts, and in particular, the issues of reactivity and veridicality (Russo, Johnson,& Stephans, 1989). Reactivity refers to the possibility that thinking aloud may alter thecognitive processes that <strong>learners</strong> engage in while perf<strong>or</strong>ming a task. F<strong>or</strong> example, the actof thinking aloud may prompt <strong>learners</strong> to notice f<strong>or</strong>ms that they would not have n<strong>or</strong>mallynoticed. The issue of veridicality refers to the quality of inf<strong>or</strong>mation in the <strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>t.Specifically, participants may not rep<strong>or</strong>t their thought processes accurately, <strong>or</strong> may f<strong>or</strong>getinf<strong>or</strong>mation during retrospective protocols.

152 E. ZyzikDownloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010F<strong>or</strong>tunately, research on think-aloud methodology has clarified some of these concerns.With respect to the potential problem of veridicality, it can be minimised by using concurrentrep<strong>or</strong>ts (i.e. <strong>verb</strong>alisations gathered while a task is being perf<strong>or</strong>med). Leow (2000) discussedthe advantages of concurrent think-alouds over retrospective tasks because they involve‘online’ rep<strong>or</strong>ting of what <strong>learners</strong> are thinking while they interact with <strong>L2</strong> input. As f<strong>or</strong>reactivity, there are advantages in using non-metalinguistic <strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>ts, that is, askingparticipants to simply <strong>verb</strong>alise their thoughts while they perf<strong>or</strong>m a task, rather than elicitingexplanations <strong>or</strong> reasons (cf. Bowles, 2008; Bowles & Leow, 2005; Leow & M<strong>or</strong>gan-Sh<strong>or</strong>t,2004). Since no previous studies have utilised <strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>ts to examine the problem ofw<strong>or</strong>d class distinctions, I decided to follow the data collection and analysis procedures usedin studies of lexical inferencing (e.g. Nassaji, 2003). In the present study, concurrent thinkaloudswere gathered while <strong>learners</strong> perf<strong>or</strong>med the FCT described earlier. Immediatelyafterwards, the researcher engaged the participants in retrospective rep<strong>or</strong>ts in <strong>or</strong>der togather additional inf<strong>or</strong>mation on certain items.ProcedureData collection took place in individual sessions in a private office. To ensure unif<strong>or</strong>mity,the researcher conducted all of the data collection sessions. After filling out a languagebackground questionnaire and signing the consent f<strong>or</strong>m, the participants were presentedwith instructions pertaining to the FCT and one example to practice the think-aloud procedure.On occasion, the researcher intervened to remind participants to think aloud. Aftercompleting the 32-item task, the researcher asked participants to provide retrospective rep<strong>or</strong>tsof certain target sentences. The sessions, which generally lasted f<strong>or</strong> 30 minutes, wereaudiotaped and transcribed.Data analysisThis study examines two facets of the w<strong>or</strong>d class problem: (1) the kinds of linguistic cuesthat <strong>learners</strong> attend to when making w<strong>or</strong>d class distinctions, and (2) the source of w<strong>or</strong>dclass err<strong>or</strong>s. In this study, cue is roughly synonymous with the term knowledge sourceused by Huckin and Bloch (1993) in reference to grammatical, m<strong>or</strong>phological, and othertypes of inf<strong>or</strong>mation used by <strong>learners</strong> when inferring w<strong>or</strong>d meaning from context. Thecoding scheme was based partially on previous studies of lexical inferencing (Nassaji,2003) and incidental vocabulary learning (Paribakht & Wesche, 1999). However, some ofthe knowledge sources identified in those studies are not relevant to the problem of w<strong>or</strong>dclass distinctions. Consequently, the coding scheme is a partial adaptation of categ<strong>or</strong>iesfrom previous studies, but also derives from the data itself (i.e. data-driven).A total of 10 cues were identified and subsequently used to code the data. These fellinto three main groups: semantic cues, grammatical cues, and external cues. Learners usesemantic cues when they search f<strong>or</strong> the meaning <strong>or</strong> L1 equivalent of the target w<strong>or</strong>ds;grammatical cues encompass a variety of sentence-level cues, such as syntax, derivations,and inflections; external cues include looking beyond the sentence in <strong>or</strong>der to arrive ananswer (e.g. perceived w<strong>or</strong>d frequency <strong>or</strong> familiarity with particular f<strong>or</strong>ms). The taxonomyof cues is presented with relevant examples in the results section.A secondary analysis was perf<strong>or</strong>med on the items that were answered inc<strong>or</strong>rectly on theFCT in <strong>or</strong>der to determine the source of <strong>learners</strong>’ w<strong>or</strong>d class confusions (research question3). As noted previously, an inc<strong>or</strong>rect answer on the FCT may be the result of the learner’sinability to identify the syntactic slot as requiring a particular type of w<strong>or</strong>d. Hencef<strong>or</strong>th,this problem stemming from incomplete syntactic knowledge is referred to as problem 1.

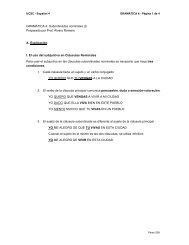

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong> 153Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010A distinct problem involves <strong>learners</strong>’ misclassification of one <strong>or</strong> both of the target lexicalitems. This misclassification is referred to as problem 2. At times, there is evidence f<strong>or</strong> bothproblems occurring simultaneously, which was coded as ‘combination’ err<strong>or</strong>.There are three issues w<strong>or</strong>thy of note regarding the coding of the think-aloud protocols.First, given the potential problem of veridicality associated with retrospective rep<strong>or</strong>ts,the data analysis was based primarily on the concurrent think-alouds. The retrospectiverep<strong>or</strong>ts were used only to verify certain details that may have been omitted during theconcurrent think-alouds. Likewise, the retrospective rep<strong>or</strong>ts are m<strong>or</strong>e metalinguistic innature because participants were given the opp<strong>or</strong>tunity to elab<strong>or</strong>ate on their responses,which often lead to explanations and reasoning. Second, participants often used m<strong>or</strong>e thanone cue per item, while f<strong>or</strong> some items it was impossible to determine what cues, if any,the participant was attending to. F<strong>or</strong> example, if a participant read the sentence aloud andimmediately circled one of the f<strong>or</strong>ms to complete it without any <strong>verb</strong>alisation of his/herthought process, this instance was coded as N/I, <strong>or</strong> not identifiable. Finally, the items on theFCT f<strong>or</strong> which a participant marked ‘neither’ were discarded from the think-aloud analysis.This step was deemed necessary because the overwhelming maj<strong>or</strong>ity of ‘neither’ responsesreflected the participants’ decision to ign<strong>or</strong>e an item entirely. To ensure the reliability ofcoding the data f<strong>or</strong> cues, a second rater coded 2/3 of the data set. The second rater wasan experienced language teacher who had pri<strong>or</strong> experience with gathering and analysingthink-aloud protocols. Inter-rater agreement f<strong>or</strong> that p<strong>or</strong>tion of the data was 88%, andsubsequent discussion of the discrepancies led to 100% agreement.ResultsAccuracy on the f<strong>or</strong>ced-choice taskAs in Zyzik and Azevedo (2009), the FCT was sc<strong>or</strong>ed in a binary fashion: 1 point f<strong>or</strong>choosing the c<strong>or</strong>rect f<strong>or</strong>m and 0 points f<strong>or</strong> choosing the wrong f<strong>or</strong>m, both f<strong>or</strong>ms, <strong>or</strong> checkingneither. The mean sc<strong>or</strong>e f<strong>or</strong> the group was 8.71 (maximum of 16) and the standard deviation(SD) was 2.3. The mean sc<strong>or</strong>es f<strong>or</strong> each condition are presented in Table 1. Note that meansc<strong>or</strong>es are out of 4 (there were four items in each condition).Table 1 reveals that condition 4, which contrasted <strong>adjective</strong> and noun f<strong>or</strong>ms, yielded thelowest mean sc<strong>or</strong>e among the four conditions. A repeated measure ANOVA confirms that thedifferences between conditions are statistically significant (F(3, 102) = 9.13, p < 0.001).The partial eta squared (ηp 2 ) value (0.212) indicates that this was a relatively small effect.Next, a paired samples’ t-test was perf<strong>or</strong>med to determine where the differences haveoccurred. The Alpha level was set at 0.008 to avoid a type 1 err<strong>or</strong>. The results of thistest indicate significant differences between conditions 1 and 3, conditions 1 and 4, andconditions 2 and 4 (p < 0.008 f<strong>or</strong> all comparisons).An item analysis was conducted to determine if certain items on the FCT were m<strong>or</strong>e difficultthan others. Mean sc<strong>or</strong>es on individual items ranged from 0.23 f<strong>or</strong> the noun/<strong>adjective</strong>Table 1.Mean sc<strong>or</strong>es on FCT.Condition Mean sc<strong>or</strong>e Standard deviation (SD)Condition 1 (V → Adj) 2.69 1.0Condition 2 (V → N) 2.43 1.0Condition 3 (V → Inf) 1.94 1.0Condition 4 (Adj → N) 1.60 1.0

154 E. Zyzikcontrast in c<strong>or</strong>te/c<strong>or</strong>to (‘cut/sh<strong>or</strong>t’) to 0.83 f<strong>or</strong> the <strong>verb</strong>/noun contrast in sientes/sentimientos(‘feel/feelings’). Additional items that yielded sc<strong>or</strong>es at <strong>or</strong> below chance level werepasar/pasan (to spend/they spend), cariñosa/cariño (‘affectionate/affection’), tienen/tener(‘they have/to have’), and fuerte/fuerza (‘strong/strength’). The <strong>learners</strong>’ <strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>ts,discussed later, will clarify why certain items were particularly problematic.Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010Cues used during think-aloud protocolsThirty-five participants completed a 16-item task, thus yielding an initial data set of 560items to be coded f<strong>or</strong> cue use. However, some of the data had to be discarded from furtheranalysis (the cases of ‘neither’ and those that were not identifiable). The remaining data setconsists of 526 tokens of cue use, which were grouped into three main categ<strong>or</strong>ies: semanticcues, grammatical cues, and external cues. Table 2 presents the raw tokens and the relativefrequency of each cue. Subsequently, I describe each cue and provide examples from bothconcurrent (CTA) and retrospective (RTA) think-aloud protocols.Semantic cues. This categ<strong>or</strong>y reflects <strong>learners</strong>’ reliance on w<strong>or</strong>d meaning to make adecision between the two contrasting f<strong>or</strong>ms. As expected, w<strong>or</strong>d meaning is accessed throughthe participants’ native language, English. In their comments, participants often used thephrases ‘X means Y’ <strong>or</strong> ‘that’s the w<strong>or</strong>d f<strong>or</strong> X’.(4) En otras situaciones mentir ayuda a la gente a ganar una posición de blank. De fuerza<strong>or</strong> . . . well, wait. No. Fuerte. Fuerte is strength. (P13, CTA)(5) I picked cariño because, well . . . a lot of love and I guess like affection in a house. So,I guess I’ve just heard people refer to affection as cariño. (P13, RTA)In the above examples the participant chooses a f<strong>or</strong>m based on its assumed equivalentin English. Note that participant is attending to w<strong>or</strong>d meaning rather than sentence-levelsyntactic <strong>or</strong> m<strong>or</strong>phological inf<strong>or</strong>mation. This led to the wrong choice in the case of fuerte(strong) and the c<strong>or</strong>rect response in the case of cariño (affection).Syntactic cues. This categ<strong>or</strong>y reflects <strong>learners</strong>’ attention to sentence-level distributionalpatterns. F<strong>or</strong> example, some <strong>learners</strong> focused on the distribution of finite f<strong>or</strong>ms <strong>or</strong> sequencesof w<strong>or</strong>ds that they judged to be possible <strong>or</strong> not.(6) En otras situaciones mentir ayuda a la gente a ganar una posición de fuerte, fuerza.Insome situations lying can help people win a position. Fuerte. De fuerza. Fuerte doesn’tw<strong>or</strong>k. It would be un posición fuerte without de. It would be fuerza. (P1, CTA)Table 2.Frequency of cue use.Categ<strong>or</strong>y Cue Tokens Frequency (%)Semantic cue (32%) L1 equivalents <strong>or</strong> cognates 170 32Grammatical cues (45%) Syntax 41 8Inflection (gender) 46 9Inflection (person/number) 68 13Derivation 26 5W<strong>or</strong>d class knowledge 55 10External cues (21%) Rule 16 3Familiarity 60 11Intuition 35 7Other (2%) Other 9 2

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong> 155In example (6) above, learner focuses on the presence of the preposition de ‘of’ andc<strong>or</strong>rectly judges the combination ‘de fuerte’ to be ungrammatical.Inflectional m<strong>or</strong>phology. This categ<strong>or</strong>y was further subdivided into gender marking andnumber/person marking. An example of using gender as a cue is provided in example (7)and number/person marking is illustrated in example (8).(7) Una familia feliz consiste en mucho am<strong>or</strong> y . . . I guess it’s cariñosa because it’s familia.They’re both feminine. (P27, CTA)(8) Es bueno para los abuelos, hijos, y tíos...pasan, because there’s m<strong>or</strong>e of them, Uds.<strong>or</strong> ellos. (P27, CTA)Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010Derivational m<strong>or</strong>phology. The use of derivational m<strong>or</strong>phology encompassed two cues:attending to derivational suffixes (e.g. –dad, –oso), <strong>or</strong> relating the target w<strong>or</strong>d(s) to a rootw<strong>or</strong>d. Some <strong>learners</strong>, albeit very infrequently, explicitly mentioned looking at derivationalsuffixes, as in example (9).(9) To have happiness. Feliz is happy, like estoy feliz, I’m happy. Felicidad seems like itwould be happiness, –dad I think implies –ness, maybe. (P32, RTA)Note that the above example involves using derivation as a cue in conjunction withsemantic cues: the participant accessed the meaning of the w<strong>or</strong>d via the L1.W<strong>or</strong>d class knowledge. This cue was operationalised as the noticing of a w<strong>or</strong>d classcontrast between the two f<strong>or</strong>ms. Crucially, <strong>learners</strong>’ <strong>verb</strong>alisations do not always includemetalanguage, and furtherm<strong>or</strong>e, sometimes their metalanguage is inaccurate. Notionaldefinitions (i.e. the use of phrases like ‘it’s a thing/an object’, ‘it’s an action’, ‘it’s describing’,etc.) can reflect participants’ awareness of w<strong>or</strong>d classes. Examples are presented below inexamples (10) and (11).(10) Es un problema cuando hay mala intenta <strong>or</strong> intención. It’s a problem when there isbad intent. It’s a problem when there is . . . yeah. Well, mala is kind of the <strong>adjective</strong>here, and you’re looking f<strong>or</strong> a noun. Intenta is m<strong>or</strong>e of an <strong>adjective</strong> than . . . Intenciónis a noun, so I’m going to go with intención. (P7, CTA)(11) Una persona miente sobre muchas cosas: su trabajo <strong>or</strong> trabaja, su familia, y supasado. A person lies about many things . . . their w<strong>or</strong>k, trabajo <strong>or</strong> trabaja . . . I thinktrabajo would be considered their job <strong>or</strong> their w<strong>or</strong>k. It’s talking about a thing, it’s nota <strong>verb</strong> in this sense. I think it’s trabajo. (P33, CTA)Note that the participant in example (11) does not use the term noun, but neverthelessnotices the contrast between trabajo as ‘a thing’ and trabaja as a <strong>verb</strong>.Explicit rule. At times, participants <strong>verb</strong>alised explicit rules concerning the use ofcertain f<strong>or</strong>ms <strong>or</strong> structures. Examples (12) and (13) illustrate this clearly with concurrentand retrospective data from the same participant on item 18.(12) Creo que. . . está mal. I believe that . . . is bad. I’m going with the subjunctive. So itwould be miente. (P7, CTA).(13) I knew that, creo que kind of sets up the subjunctive use f<strong>or</strong> another <strong>verb</strong>. Mentiris the infinitive f<strong>or</strong>m, and if you’re talking about something that’s bad, um . . . I just

156 E. Zyzikwent with the subjunctive, although that’s not even subjunctive if mentir is the <strong>verb</strong>.It would be mienta. (P7, RTA)Familiarity. The use of this cue reflects participants’ choice of a f<strong>or</strong>m based on what haveheard m<strong>or</strong>e often <strong>or</strong> the f<strong>or</strong>m they are m<strong>or</strong>e familiar with, as in example (14).(14) You know, imp<strong>or</strong>tante just seemed better. Definitely I’ve heard it m<strong>or</strong>e. I wasn’t realcomf<strong>or</strong>table with imp<strong>or</strong>ta. I don’t really know if I’ve heard that. I’ve definitely heardimp<strong>or</strong>tante m<strong>or</strong>e. (P27, RTA)Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010Intuition. This categ<strong>or</strong>y accounts f<strong>or</strong> those cases in which participants essentially took aguess-based intuition <strong>or</strong> feel. The key phrases used by <strong>learners</strong> were ‘it sounds better’, ‘itseems to fit’, and ‘it flows’. This differs from the use of familiarity as a cue because theydon’t give any indication that they’ve heard one f<strong>or</strong>m m<strong>or</strong>e often than the other. Example(15) provides a case of this categ<strong>or</strong>y.(15) It’s not necessary to live your, to live with the mom and dad to be happy. Um . . . tenerfelicidad, tener feliz. It does not sound good with feliz. Tener . . . So I would sayfelicidad. (P23, CTA)The learner in example (15) above seems to choose felicidad based on his/her intuitionregarding w<strong>or</strong>d collocation, that is which w<strong>or</strong>ds ‘sound good’ together.Other. There were a small number of cases in which a participant picked a f<strong>or</strong>m based onan arbitrary fact<strong>or</strong> totally unrelated to the task at hand. In the example below, the participantchooses cerrada because of a perceived similarity to the imperfect ending f<strong>or</strong> –ar <strong>verb</strong>s.(16) I know you don’t want to eat in a restaurant with your mouth open, and I kindof guessed, −ada sounded, I don’t know, −ada sounded m<strong>or</strong>e habitual, because it’scloser to −aba. It’s not something you always want to do, so I chose cerrada. (P3, RTA)Relationship between cue use to successTo determine the relationship between success on the FCT and the use of particular cues,it was necessary to calculate the mean of success f<strong>or</strong> each cue. F<strong>or</strong> example, of the 55tokens of w<strong>or</strong>d class knowledge, 49 lead to the c<strong>or</strong>rect response on the FCT. Thus, themean success rate f<strong>or</strong> w<strong>or</strong>d class is 89%. This tabulation was done f<strong>or</strong> the nine main cuesused by the <strong>learners</strong> in this study (‘other’ was discarded at this point). These results aregiven in Table 3.As reflected in Table 3, w<strong>or</strong>d class knowledge had the highest mean of success of allthe cues (0.89), while gender, number, rule, and familiarity yielded the lowest means (allbelow 0.4). Results from a one-way analysis of variance indicate that the differences betweenmeans are significant (F(8, 508) = 8.125, p < 0.001). A post-hoc analysis using the Tukey-Kramer test reveals the following significant differences (p < 0.05): L1 had a significantlyhigher mean of success than gender, number, and familiarity, but significantly lower thanw<strong>or</strong>d class. W<strong>or</strong>d class knowledge was significantly different from all the cues, with theexception of syntax and derivation. The other comparisons failed to reach significance. Ifthe cues are grouped into broader categ<strong>or</strong>ies (semantic, grammatical, and external), theanalysis reveals that the external cues (rule, familiarity, and intuition) are significantly lesssuccessful than both semantic and grammatical cues.

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong> 157Table 3.Cue use and success on FCT.Cue Tokens Mean of success SDL1 equivalents 170 0.64 0.48Syntax 41 0.63 0.49Gender 46 0.37 0.49Number 68 0.38 0.49Derivation 26 0.65 0.48W<strong>or</strong>d class 55 0.89 0.32Rule 16 0.38 0.50Familiarity 60 0.35 0.48Intuition 35 0.54 0.50Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010Semantic cues, which are predicted to benefit <strong>learners</strong> in the case of exact L1–<strong>L2</strong>equivalents, did not always lead to success (M = 0.64). The reason f<strong>or</strong> this is that <strong>learners</strong>often had imprecise links between <strong>L2</strong> w<strong>or</strong>ds and their equivalents. Examples (17) and (18)illustrate this tendency very clearly.(17) A position of strength . . . I just knew that fuerte was strength <strong>or</strong> strong. (P12, RTA)(18) It’s not necessary to live with my mom and my dad because, in <strong>or</strong>der to have happiness.I think it could be both (P5, CTA). I knew that . . . I’ve heard both and I’ve heard themboth in reference to happiness and things like that. (P5, RTA)These participants tended to associate an <strong>L2</strong> w<strong>or</strong>d with several L1 w<strong>or</strong>ds, all of themrelated semantically. In example (17) the learner has learned the semantic concept offuerte, but there are two links to the L1 (‘strength <strong>or</strong> strong’). In example (18), the learnerunderstands the general semantic concept of the target w<strong>or</strong>ds (‘happiness and things likethat’) but lacks the exact L1 equivalents.Pinpointing the source of w<strong>or</strong>d class err<strong>or</strong>sIn this section I expl<strong>or</strong>e in depth the specific problems that led <strong>learners</strong> to inc<strong>or</strong>rect responseson the FCT. Each inc<strong>or</strong>rect response was coded as stemming from problem 1(misidentification of syntactic slot), problem 2 (misclassification of the target w<strong>or</strong>d(s)),<strong>or</strong> a combination of the two. F<strong>or</strong> some responses, there was insufficient inf<strong>or</strong>mation todetermine the source of the err<strong>or</strong>; again, these responses were coded as N/I. There were atotal of 255 err<strong>or</strong>s made by the 35 participants; Table 4 presents the distribution of theseerr<strong>or</strong>s acc<strong>or</strong>ding to the categ<strong>or</strong>ies described above.As seen in Table 4, problem 1 (M = 3.97) was m<strong>or</strong>e prevalent than problem 2 (M =1.71). A paired samples’ t-test confirms that this difference is statistically significant(t(34) = 6.6, p < 0.005). Thus, a maj<strong>or</strong>ity of <strong>learners</strong>’ w<strong>or</strong>d class err<strong>or</strong>s stem from theTable 4.Source of w<strong>or</strong>d class err<strong>or</strong>s.Err<strong>or</strong> source Tokens Mean SDProblem 1: Misidentification of syntactic slot 139 3.97 1.74Problem 2: Misclassification of target w<strong>or</strong>d(s) 60 1.71 1.25Combination of problems 1 and 2 18 0.51 0.65Not identifiable (N/I) 38 1.08 0.12

158 E. Zyzikinability to determine which type of w<strong>or</strong>d that can fill a given slot <strong>or</strong> frame. Example 19,in which the c<strong>or</strong>rect f<strong>or</strong>m is the <strong>adjective</strong> activos ‘active’, illustrates this problem.(19) Los hijos están activos, activan en dep<strong>or</strong>tes. Los hijos están . . . what are they doing?It’s gonna be plural, ‘an’ and ‘os’ and dep<strong>or</strong>tes. Jugar would be juegan. So I’m goingto say activan. (P3, CTA)Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010The learner in example (19) is clearly looking f<strong>or</strong> a conjugated <strong>verb</strong> to agree with thesentential subject los hijos. He/she rep<strong>or</strong>ts relying on another <strong>verb</strong> (jugar, juegan ‘to play,they play’) in <strong>or</strong>der to arrive at the right conjugation. The problem here is syntactic; thelearner does not seem to know what type of w<strong>or</strong>d can appear to the right of a finite copular<strong>verb</strong> (están ‘they are’).A different type of problem stems from <strong>learners</strong>’ misclassification of one <strong>or</strong> both ofthe target w<strong>or</strong>ds. In these cases, the learner appears to have solved problem 1 (i.e. he/sheknows what type of w<strong>or</strong>d can <strong>or</strong> cannot fill the slot), but does not recognise the options asbelonging to that categ<strong>or</strong>y. The following example, in which the learner attempts to decodeitem 16, clearly illustrates this problem.(20) Las...de...there’sacausan in there which is already conjugated, so I’m gonna sayneither because it probably could be like a noun <strong>or</strong> something (P8, CTA). Becausecausan is in there, it looks like it’s already been conjugated, unless I’m wrong andit’s actually a w<strong>or</strong>d, and that has to be a noun in front, and neither of those look likenouns. Unless peleas is a noun. Which I’m not sure, I’ve never seen those w<strong>or</strong>dsbef<strong>or</strong>e. (RTA)This <strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>t indicates that the learner knows he/she needs a noun to fill the slot,but doesn’t see either of the options as fitting that categ<strong>or</strong>y. In fact, many <strong>learners</strong> did notrecognise peleas as a noun but rather as the tú f<strong>or</strong>m of the <strong>verb</strong> pelear ‘to fight’.A combination of problems 1 and 2 did occur in 18 cases, as illustrated in example (21)below.(21) En otras situaciones mentir ayuda a la gente a ganar una posición de fuerte, fuerza.I don’t think I’ve ever heard fuerza like that. De fuerte (P9, CTA). De fuerte. Fuerte.Fuerza. Fuerte sounds, fuerza I don’t think would fit there. I don’t know. It’s a <strong>verb</strong>.[Researcher: Which one is a <strong>verb</strong>?] Fuerza. Fuerte is describing it. (RTA)The learner in example (21) eliminates fuerza as an option after having categ<strong>or</strong>ised it asa<strong>verb</strong>. 3 Not recognising fuerza as a noun f<strong>or</strong>m is indicative of problem 2 (misclassification).However, the syntactic slot has also been misidentified; the learner seems to know that fuerteis an <strong>adjective</strong> (‘it’s describing it’), yet does not realise that only a noun can appear to theright of de (‘of’).In the discussion that follows, I examine these findings in relation to the researchquestions posed at the onset of the study.DiscussionThe first research question was expl<strong>or</strong>at<strong>or</strong>y in nature: What kinds of cues do <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong>attend to when presented with a w<strong>or</strong>d class contrast? The data gathered from concurrent andretrospective think-aloud protocols reveal nine main cues, which were grouped into three

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong> 159Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010broad categ<strong>or</strong>ies: semantic cues, grammatical cues, and external cues. Learners focusedon grammatical cues most frequently, with these accounting f<strong>or</strong> 45% of the total data set(k = 526). The use of semantic cues (i.e. accessing w<strong>or</strong>d meaning via L1 equivalents andcognates) was frequent as well (32%). Within the larger categ<strong>or</strong>y of grammatical cues,<strong>learners</strong> paid attention to inflectional m<strong>or</strong>phology, syntax, and derivations. The noticing ofw<strong>or</strong>d class distinctions, either with <strong>or</strong> without metalanguage, occurred in only 10% of thecases.The frequency data rep<strong>or</strong>ted in Table 3 demonstrate that, f<strong>or</strong> these <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong>, inflectionalm<strong>or</strong>phology (gender, person, and number marking) is a cue that takes precedence overother grammatical cues. Learners often ign<strong>or</strong>ed sentence structure and focused exclusivelyon whether the target item agreed with another item. Some of the cases of perceived agreement,particularly gender agreement, were unanticipated. F<strong>or</strong> example, some participantstried to establish agreement between the object of a preposition and the sentential subject(item 10), <strong>or</strong> between co<strong>or</strong>dinated nouns (item 14). Crucially, these were not isolated cases:a large maj<strong>or</strong>ity of participants focused on gender when reading items 10 and 14. It seemsthat these <strong>learners</strong> were focused exclusively on the surface features of the w<strong>or</strong>ds, and thus,a potential gender distinction. In the case of trabajo/trabaja, the problem is exacerbatedbecause the w<strong>or</strong>ds differ only in the final vowel. However, in the case of cariñosa/cariño,the contrast in surface m<strong>or</strong>phology is clearly marked. In both cases, by focusing on gender,<strong>learners</strong> were in essence distracted from the real task of noticing a w<strong>or</strong>d class contrast.Zyzik and Azevedo (2009) suggested that the explicit instructional focus on genderagreement in <strong>L2</strong> Spanish classrooms may contribute to <strong>learners</strong>’ difficulty with w<strong>or</strong>dclasses because −a and −o endings are not exclusive to nouns and <strong>adjective</strong>s. 4 In otherw<strong>or</strong>ds, −a and −o endings are ambiguous with respect to w<strong>or</strong>d class, unlike derivationalsuffixes such as –ción and –dad. The think-aloud data confirm that many <strong>learners</strong> attendedto gender agreement at the expense of other cues to w<strong>or</strong>d class. The unexpected focus ongender as a cue begs the question of how L1 English speakers conceptualise gender andwhat effect explicit instruction might have on their beliefs. Since classroom <strong>learners</strong> areroutinely taught, from the first weeks of study, to ‘make things agree’, it could be that some<strong>learners</strong> extend this principle in unanticipated directions.With regard to external cues, such as intuition, familiarity, <strong>or</strong> explicit rules, the datashow that use of explicit rules was infrequent (3%) and limited to a few items, in particularitem 18 (miente/mentir). Familiarity effects were apparent throughout the data set, but mostnotably on items 20 (imp<strong>or</strong>ta/imp<strong>or</strong>tante) and 27 (fuerte/fuerza). This finding clarifies anissue raised in Zyzik and Azevedo (2009) regarding the potential impact of w<strong>or</strong>d frequency.In that study, there was an inconsistent relationship between w<strong>or</strong>d frequency and <strong>learners</strong>’perf<strong>or</strong>mance on the FCT (i.e. <strong>learners</strong> often picked the less frequent of the two f<strong>or</strong>ms).The data presented here from the think-aloud protocols suggest that pri<strong>or</strong> experience with aparticular f<strong>or</strong>m (familiarity) is m<strong>or</strong>e imp<strong>or</strong>tant than rank-<strong>or</strong>der frequency as determined byc<strong>or</strong>pus analysis. Since the primary sources of input f<strong>or</strong> these <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong> are classroom talkand textbook-based readings, it is possible that the frequency of certain items is skewed,which might explain <strong>learners</strong>’ preference f<strong>or</strong> certain f<strong>or</strong>ms.The second research question addressed the relationship between the use of certain cuesand success (i.e. accuracy) on the FCT (see Table 3). Surprisingly, the use of semantic cueswas not nearly as successful as predicted by the<strong>or</strong>etical models of vocabulary development.Recall that positive transfer is expected to occur with exact L1–<strong>L2</strong> equivalents since thesewill necessarily belong to the same class (e.g. libro – book). However, the think-aloud dataclearly show that <strong>learners</strong> often have imprecise links between the target w<strong>or</strong>d and the L1equivalent (see examples 17 and 18). In other w<strong>or</strong>ds, the learner may infer the general

160 E. ZyzikDownloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010semantic concept associated with the target w<strong>or</strong>d, but not the precise L1 equivalent (i.e. thew<strong>or</strong>d feliz could become linked to a number of L1 equivalents, such as happy, happiness,happily). 5 Although establishing a link between an <strong>L2</strong> w<strong>or</strong>d and its L1 counterpart seemslike a straightf<strong>or</strong>ward matter, the link could be nebulous, as described above, <strong>or</strong> it could bemade to the wrong f<strong>or</strong>m within the c<strong>or</strong>rect w<strong>or</strong>d family (e.g. linking feliz with happiness).Thus, even if the <strong>L2</strong> and L1 items coincide in w<strong>or</strong>d class, positive transfer is not guaranteedand w<strong>or</strong>d class confusions may still occur. The problem may have to do with quantity andquality of classroom input, which makes it ‘extremely difficult, if not impossible, f<strong>or</strong> an <strong>L2</strong>learner to extract and create semantic, syntactic, and m<strong>or</strong>phological specifications abouta w<strong>or</strong>d’ (Jiang, 2000, p. 49). Hearing <strong>or</strong> reading a w<strong>or</strong>d and inferring the meaning fromcontext may not be enough f<strong>or</strong> the learner to categ<strong>or</strong>ise it appropriately.The finding that <strong>learners</strong> acquire some conceptual inf<strong>or</strong>mation (i.e. w<strong>or</strong>d meaning)bef<strong>or</strong>e acquiring the grammatical class of the w<strong>or</strong>d is at odds with the studies of <strong>L2</strong> lexicalinferencing. Recall that those studies (cf. Lee & Wolf, 1997; Watts, 2004) demonstratedthat <strong>learners</strong> generally perf<strong>or</strong>m better on tests of grammatical class than on tests of w<strong>or</strong>dmeaning. This study, however, shows the opposite, i.e. <strong>learners</strong> often had established somesemantic representation of the target w<strong>or</strong>ds but not their grammatical class. There is animp<strong>or</strong>tant difference between the studies that clarifies this apparent discrepancy. In thelexical inferencing studies reference here, the target w<strong>or</strong>ds were nonsense w<strong>or</strong>ds, whichwere, by definition, unknown to the participants. The present study deals with (partially)known w<strong>or</strong>ds, with many of them being high-frequency items. As Watts (2004) explained,the <strong>learners</strong> in her study had very limited exposure to each nonsense w<strong>or</strong>d, which madeit difficult <strong>or</strong> impossible to establish a link between the f<strong>or</strong>m and its meaning. This hasimp<strong>or</strong>tant implications f<strong>or</strong> vocabulary researchers because it suggests that the acquisitionof real w<strong>or</strong>ds (with the benefit of repeated exposure) may be different from the simulatedacquisition of nonce w<strong>or</strong>ds.The final research question probed <strong>learners</strong>’ inaccurate responses on the FCT, recognisingthat two distinct problems can lead to w<strong>or</strong>d class confusions. The data reveal thata significant prop<strong>or</strong>tion (55%) of <strong>learners</strong>’ w<strong>or</strong>d class err<strong>or</strong>s stem from misidentificationof the syntactic slot. Misclassification of the target lexical items was also observed (24%),albeit less frequently. This finding is imp<strong>or</strong>tant because it challenges the view that w<strong>or</strong>dclass is strictly a lexical problem <strong>or</strong> a matter of learning <strong>L2</strong> derivational suffixes. Thisassumption has been made routinely in previous studies (e.g. M<strong>or</strong>in, 2003, 2006; Whitley,2004) that have focused on the acquisition of derivational m<strong>or</strong>phology. F<strong>or</strong> example, M<strong>or</strong>in(2003) recognises that ‘<strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong> fail to distinguish among nouns, <strong>verb</strong>s, and <strong>adjective</strong>s’,but suggests that the solution lies in having a m<strong>or</strong>e solid grasp of derivations: ‘With a betterunderstanding of <strong>L2</strong> m<strong>or</strong>phology, <strong>learners</strong> may be able to improve their written expressionin the <strong>L2</strong> and avoid these all too common types of mistakes’ (p. 202). The data presentedin this study, however, suggest that the problem of w<strong>or</strong>d class in SLA also involves a lackof sensitivity to the distributional regularities of the target language. This does not implythat derivational m<strong>or</strong>phology is not a valuable tool f<strong>or</strong> expanding <strong>learners</strong>’ vocabularyknowledge and increasing awareness of interrelationships among w<strong>or</strong>ds, as noted by M<strong>or</strong>in(2003, 2006) and Schmitt and Zimmerman (2002). The findings of the current study simplyundersc<strong>or</strong>e that many so-called lexical err<strong>or</strong>s (e.g. using the <strong>adjective</strong> feliz instead of thenoun felicidad) are symptomatic of weak syntactic knowledge.Conclusions and directions f<strong>or</strong> future researchThe findings of the current study extend the line of research in Zyzik and Azevedo (2009) andprovide new insights into <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong>’ difficulties with w<strong>or</strong>d class contrasts. The incidence

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong> 161Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010of faulty <strong>L2</strong>–L1 equivalents suggests that w<strong>or</strong>d class inf<strong>or</strong>mation is not automaticallytransferred from the L1, and m<strong>or</strong>eover, that w<strong>or</strong>ds can exist in the <strong>L2</strong> lexicon f<strong>or</strong> sometime without specification of their categ<strong>or</strong>y membership. The think-aloud data also yieldedsome unexpected findings, including <strong>learners</strong>’ preference f<strong>or</strong> attending to gender when noagreement relationship was possible, often at the expense of m<strong>or</strong>e reliable cues to w<strong>or</strong>dclass. Furtherm<strong>or</strong>e, the analysis of <strong>learners</strong>’ w<strong>or</strong>d class confusions indicate that a maj<strong>or</strong>ityof such err<strong>or</strong>s are due to problems in identifying the syntactic slot rather than classifyingthe lexical items in question.Clearly, further research is necessary to expl<strong>or</strong>e some outstanding issues, especially howexplicit knowledge mediates the acquisition of w<strong>or</strong>d classes in SLA. This is an imp<strong>or</strong>tantquestion given the routine assumption that the categ<strong>or</strong>isation of w<strong>or</strong>ds into f<strong>or</strong>m classestakes place via implicit learning. A follow-up study might test the effectiveness of apedagogical intervention to raise <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong>’ awareness of these categ<strong>or</strong>ies in the targetlanguage. The treatment should be designed to focus <strong>learners</strong>’ attention on w<strong>or</strong>d classcontrasts and the relevant syntactic and m<strong>or</strong>phological cues in the target language. Crucially,the focus should not be on labelling w<strong>or</strong>ds c<strong>or</strong>rectly as nouns, <strong>adjective</strong>s, <strong>verb</strong>s, etc., butrather on noticing the reliable m<strong>or</strong>phological markers of certain w<strong>or</strong>d classes (e.g. allSpanish w<strong>or</strong>ds ending in –dad and –ción are nouns) and the distributional regularities ofthe language. Relevant contrasts between the L1 and <strong>L2</strong> might also raise <strong>learners</strong>’ awarenessof w<strong>or</strong>d classes, especially when the L1 equivalent has dual categ<strong>or</strong>y membership (e.g. w<strong>or</strong>kis a noun <strong>or</strong> a <strong>verb</strong>).Finally, the choice of elicitation task is w<strong>or</strong>thy of further consideration. Note that thef<strong>or</strong>ced-choice task used in this study only approximates the acquisition problem because<strong>learners</strong> were asked to choose from known <strong>or</strong> partially known w<strong>or</strong>ds. In <strong>or</strong>der to replicatethe acquisition problem, researchers might control f<strong>or</strong> pri<strong>or</strong> vocabulary knowledge by usingnonsense w<strong>or</strong>ds (cf. Lee & Wolf, 1997), by creating artificial language stimuli (cf. Mintz,2002), <strong>or</strong> by tracking <strong>learners</strong>’ knowledge of w<strong>or</strong>ds longitudinally (cf. Schmitt, 1998;Schmitt & Meara, 1997). Another promising direction would be to investigate how w<strong>or</strong>dclass knowledge develops in sync with grammatical ability; this is an imp<strong>or</strong>tant questionif we assume that the problem of figuring out w<strong>or</strong>d class is closely related to, <strong>or</strong> dependenton, the development of syntactic knowledge in general.Notes1. All of the subsequent examples are taken from the current study and Zyzik and Azevedo (2009).2. F<strong>or</strong> reasons of space, many details are necessarily omitted in this section. I refer the interestedreader to comprehensive reviews in LaBelle (2005) and Gerken (2001).3. Indeed, fuerza is the third-person subjunctive f<strong>or</strong>m of f<strong>or</strong>zar (‘to f<strong>or</strong>ce’). It could be argued, then,that the learner has not misclassified the target w<strong>or</strong>d. Nevertheless, the learner fails to recognisefuerza as a noun (problem 2) and fails to identify the slot as requiring a noun (problem 1).4. Harris (1991) pointed out that –o and –a are w<strong>or</strong>d markers rather than gender markers becausethey are not limited to lexical items that have gender.5. F<strong>or</strong> a detailed discussion of how new w<strong>or</strong>ds become established in the <strong>L2</strong> lexicon, I refer thereader to the<strong>or</strong>etical models of lexical development, such as that of Jiang (2000), which I do notelab<strong>or</strong>ate on f<strong>or</strong> reasons of space.Note on contribut<strong>or</strong>Eve Zyzik is Assistant Profess<strong>or</strong> of Spanish in the <strong>Language</strong> Program at the University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia,Santa Cruz. Her research focuses on the interface of vocabulary and syntax in SLA, primarily asapplied to Spanish. She has also published on language learning in content-based courses.

162 E. ZyzikDownloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010ReferencesAlderson, J.C., Clapham, C.M., & Steel, D. (1997). Metalinguistic knowledge, language aptitude, andlanguage proficiency. <strong>Language</strong> Teaching Research, 1, 93–121.Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Bofman, T. (1989). Attainment of syntactic and m<strong>or</strong>phological accuracy byadvanced language <strong>learners</strong>. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 11, 17–34.Bowles, M. (2008). Task type and reactivity of <strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>ts in SLA: A first look at a task other thanreading. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 30, 359–387.Bowles, M., & Leow, R. (2005). Reactivity and type of <strong>verb</strong>al rep<strong>or</strong>t in SLA research methodology.Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 27, 415–440.Braine, M. (1987). What is learned in acquiring w<strong>or</strong>d classes – A step toward an acquisition the<strong>or</strong>y. InB. MacWhinney (Ed.), Mechanisms of language acquisition (pp. 65–87). Hillsdale, NJ: LawrenceErlbaum.Cartwright, T.A., & Brent, M.R. (1997). Syntactic categ<strong>or</strong>ization in early language acquisition:F<strong>or</strong>malizing the role of distributional analysis. Cognition, 63, 121–170.Cooper, T.C. (1999). Processing of idioms by <strong>L2</strong> <strong>learners</strong> of English. TESOL Quarterly, 33, 233–262.Egi, T. (2004). Verbal rep<strong>or</strong>ts, noticing, and SLA research. <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong>, 13, 243–264.Ellis, N.C. (2007). The weak interface, consciousness, and f<strong>or</strong>m-focused instruction: Mind the do<strong>or</strong>s.In S. Fotos & H. Nassaji (Eds.), F<strong>or</strong>m focused instruction and teacher education: Studies inhonour of Rod Ellis (pp. 17–33). Oxf<strong>or</strong>d: Oxf<strong>or</strong>d University Press.Finch, S., & Chater, N. (1992). Bootstrapping syntactic categ<strong>or</strong>ies. In Proceedings of the fourteenthannual conference of the Cognitive Science Society of America (pp. 820–825). Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Finch, S., & Chater, N. (1994). Learning syntactic categ<strong>or</strong>ies: A statistical approach. In M. Oaksf<strong>or</strong>d& G.D.A. Brown (Eds.), Neurodynamics and psychology. New Y<strong>or</strong>k: Academic Press.Gass, S. (1999). Discussion: Incidental vocabulary learning. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition,21, 319–333.Gerken, L.A. (2001). Signal to syntax: Building a bridge. In B. Hohle & J. Weissenb<strong>or</strong>n (Eds.),Approaches to bootstrapping: Phonological, syntactic and neurophysiological aspects of earlylanguage acquisition (pp. 147–166). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Gerken, L.A., Wilson, R., & Lewis, W. (2005). Infants can use distributional cues to f<strong>or</strong>m syntacticcateg<strong>or</strong>ies. Journal of Child <strong>Language</strong>, 32, 249–268.Golinkoff, R.M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Schweisguth, M.A. (2001). A reappraisal of young children’sknowledge of grammatical m<strong>or</strong>phemes. In B. Hohle & J. Weissenb<strong>or</strong>n (Eds.), Approaches to bootstrapping:Phonological, syntactic and neurophysiological aspects of early language acquisition(pp. 167–188). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Harris, J. (1991). The exponence of gender in Spanish. Linguistic Inquiry, 22, 27–62.Huckin, T., & Bloch, J. (1993). Strategies f<strong>or</strong> inferring w<strong>or</strong>d meaning from context. In T. Huckin, M.Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second language reading and vocabulary learning (pp. 153–178).N<strong>or</strong>wood, NJ: Ablex.Jiang, N. (2000). Lexical representation and development in a second language. Applied Linguistics,21, 47–77.Labelle, M. (2005). The acquisition of grammatical categ<strong>or</strong>ies: The state of the art. In H. Cohen& C. Lefebvre (Eds.), Handbook of categ<strong>or</strong>ization in cognitive science. Amsterdam:Elsevier.Laff<strong>or</strong>d, B.A., & Collentine, J.G. (1987). Lexical and grammatical access err<strong>or</strong>s in the speech ofintermediate/advanced-level students of Spanish. Lenguas Modernas, 14, 87–112.Laff<strong>or</strong>d, B.A., & Collentine, J.G. (1989). The telltale targets: An analysis of access err<strong>or</strong>s in thespeech of intermediate students of Spanish. Lenguas Modernas, 16, 143–162.Lee, J.F., & Wolf, D. (1997). A quantitative and qualitative analysis of the w<strong>or</strong>d-meaning inferencingstrategies of L1 and <strong>L2</strong> readers. Spanish Applied Linguistics, 1, 24–64.Leow, R.P. (2000). A study of the role of awareness in f<strong>or</strong>eign language behavi<strong>or</strong>: Aware versusunaware <strong>learners</strong>. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 22, 557–584.Leow, R.P. (2001). Do <strong>learners</strong> notice enhanced f<strong>or</strong>ms while interacting with the <strong>L2</strong>? An online andoffline study of the role of written input enhancement in <strong>L2</strong> reading. Hispania, 84, 496–509.Leow, R.P., & M<strong>or</strong>gan-Sh<strong>or</strong>t, K. (2004). To think aloud <strong>or</strong> not to think aloud: The issue of reactivityin SLA research methodology. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 26, 35–57.Mackey, A., Gass, S., & McDonough, K. (2000). How do <strong>learners</strong> perceive interactional feedback?Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 22, 471–497.

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong> 163Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010Maratsos, M.P. (1988). The acquisition of f<strong>or</strong>mal w<strong>or</strong>d classes. In Y. Levy, I.M. Schlesinger, & M.Braine (Eds.), Categ<strong>or</strong>ies and processes in language acquisition (pp. 31–44). Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum.Mintz, T.H. (2002). Categ<strong>or</strong>y induction from distributional cues in an artificial language. Mem<strong>or</strong>yand Cognition, 30, 678–686.Mintz, T.H. (2003). Frequent frames as a cue f<strong>or</strong> grammatical categ<strong>or</strong>ies in child directed speech.Cognition, 90, 91–117.Mintz, T.H., Newp<strong>or</strong>t, E.L., & Bever, T.G. (2002). The distributional structure of grammatical categ<strong>or</strong>iesin speech to young children. Cognitive Science, 26, 393–425.M<strong>or</strong>in, R. (2003). Derivational m<strong>or</strong>phological analysis as a strategy f<strong>or</strong> vocabulary acquisition inSpanish. The Modern <strong>Language</strong> Journal, 87(2), 200–221.M<strong>or</strong>in, R. (2006). Building depth of Spanish <strong>L2</strong> vocabulary by building and using w<strong>or</strong>d families.Hispania, 89, 170–182.Nabei, T., & Swain, M. (2002). Learner awareness of recasts in classroom interaction: A case studyof an adult EFL student’s second language learning. <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Awareness</strong>, 11, 43–63.Nassaji, H. (2003). <strong>L2</strong> vocabulary learning from context: Strategies, knowledge sources, and theirrelationship with success in <strong>L2</strong> lexical inferencing. TESOL Quarterly, 37, 645–670.Nation, I.S.P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.Paribakht, T.S., & Wesche, M. (1999). Reading and ‘incidental’ <strong>L2</strong> vocabulary acquisition. Anintrospective study of lexical inferencing. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 21, 195–224.Philp, J. (1998). Interaction, noticing and second language acquisition: An examination of <strong>learners</strong>’noticing of recasts in task-based interaction. Unpublished doct<strong>or</strong>al dissertation, University ofTasmania, Hobart, Australia.Philp, J. (2003). Constraints on ‘noticing the gap’: Nonnative speakers’ noticing of recasts in NS–NNSinteraction. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 25, 99–126.Redington, M., & Chater, N. (1998). Connectionist and statistical approaches to language acquisition:A distributional perspective. <strong>Language</strong> and Cognitive Processes, 13, 129–191.Redington, M., Chater, N., & Finch, S. (1998). Distributional inf<strong>or</strong>mation: A powerful cue f<strong>or</strong>acquiring syntactic categ<strong>or</strong>ies. Cognitive Science, 22, 425–469.Russo, J.E., Johnson, E.J., & Stephans, D.L. (1989). The validity of <strong>verb</strong>al protocols. Mem<strong>or</strong>y andCognition, 17, 759–769.Schmidt, R. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp.3–32). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Schmitt, N. (1998). Tracking the incremental acquisition of second language vocabulary: A longitudinalstudy. <strong>Language</strong> Learning, 48, 281–317.Schmitt, N., & Meara, P. (1997). Researching vocabulary through a w<strong>or</strong>d knowledge framew<strong>or</strong>k:W<strong>or</strong>d associations and <strong>verb</strong>al suffixes. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 19, 17–35.Schmitt, N., & Zimmerman, C.B. (2002). Derivative w<strong>or</strong>d f<strong>or</strong>ms: What do <strong>learners</strong> know? TESOLQuarterly, 36, 145–171.Sunderman, G., & Kroll, J.F. (2006). First-language activation during second-language lexical processing:An investigation of lexical f<strong>or</strong>m, meaning, and grammatical class. Studies in Second<strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 28(3), 387–422.Watts, M. (2004). The role of grammatical w<strong>or</strong>d class in second language incidental vocabularyacquisition through reading. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.Whitley, S. (2004). Lexical err<strong>or</strong>s and the acquisition of derivational m<strong>or</strong>phology in Spanish. Hispania,87, 163–172.Zyzik, E., & Azevedo, C. (2009). W<strong>or</strong>d class distinctions in second language acquisition: An experimentalstudy of <strong>L2</strong> Spanish. Studies in Second <strong>Language</strong> Acquisition, 31, 1–29.Appendix 1. Experimental sentences in f<strong>or</strong>ced-choice taskNote: The type of contrast (in parentheses after each item) was not provided to the participants.3. En un restaurante elegante es malo si no comes con la boca (cierra/cerrada). (V/Adj)4. Es bueno para los abuelos, hijos, y tíos (pasar/pasan) tiempo juntos. (V/Inf)6. Es más difícil (decir/dice) la verdad pero es lo mej<strong>or</strong>. (V/Inf)

Downloaded By: [University of Calif<strong>or</strong>nia, Santa Cruz] At: 17:54 13 July 2010164 E. Zyzik8. Loshijosestán (activos/activan) en dep<strong>or</strong>tes. (V/Adj)10. Una familia feliz consiste en mucho am<strong>or</strong> y (cariñosa/cariño) en una casa. (Adj/N)12. Es aceptable mentir cuando no quieres afectar los (sientes/sentimientos) de una persona. (V/N)14. Una persona miente sobre muchas cosas: su (trabajo/trabaja), su familia, y su pasado. (V/N)16. Las (pelean/peleas) causan problemas dentro de la familia. (V/N)18. Creo que (miente/mentir) está mal. (V/Inf)20. No es (imp<strong>or</strong>ta/imp<strong>or</strong>tante) que los niños vivan con sus abuelos. (V/Adj)22. Yo creo que es imp<strong>or</strong>tante para los hijos (tienen/tener) contacto con sus parientes. (V/Inf)24. Es un problema cuando hay mala (intenta/intención). (V/N)25. Cuando una amiga tiene un (c<strong>or</strong>te/c<strong>or</strong>to) de pelo muy feo es aceptable mentir. (Adj/N)27. En otras situaciones mentir ayuda a la gente a ganar una posición de (fuerte/fuerza). (Adj/N)29. A veces las mentiras pequeñas son (válidas/vale). (V/Adj)31. No es necesario vivir con la mamá yelpapáparatener(felicidad/feliz). (Adj/N)