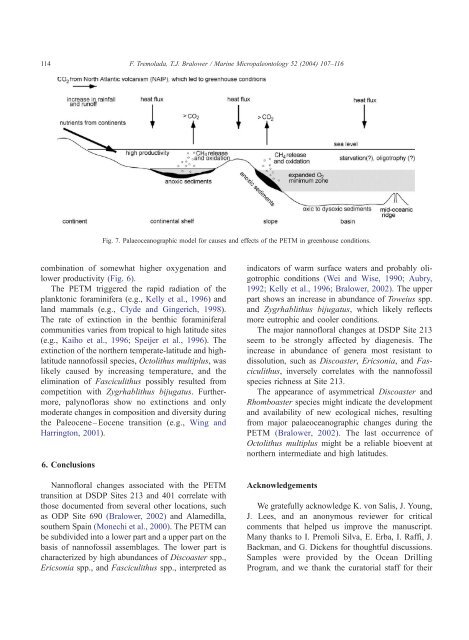

114F. <strong>Tremolada</strong>, T.J. <strong>Bralower</strong> / Marine Micropaleontology 52 (<strong>2004</strong>) 107–116Fig. 7. Palaeoceanographic model for causes <strong>and</strong> effects of the PETM in greenhouse conditions.combination of somewhat higher oxygenation <strong>and</strong>lower productivity (Fig. 6).The PETM triggered the rapid radiation of theplanktonic foraminifera (e.g., Kelly et al., 1996) <strong>and</strong>l<strong>and</strong> mammals (e.g., Clyde <strong>and</strong> Gingerich, 1998).The rate of extinction in the benthic foraminiferalcommunities varies from tropical to high latitude sites(e.g., Kaiho et al., 1996; Speijer et al., 1996). Theextinction of the northern temperate-latitude <strong>and</strong> highlatitudenannofossil species, Octolithus multiplus, waslikely caused by increasing temperature, <strong>and</strong> theelimination of Fasciculithus possibly resulted fromcompetition with Zygrhablithus bijugatus. Furthermore,palynofloras show no extinctions <strong>and</strong> onlymoderate changes in composition <strong>and</strong> diversity duringthe Paleocene–Eocene transition (e.g., Wing <strong>and</strong>Harrington, 2001).6. ConclusionsNannofloral changes associated with the PETMtransition at DSDP Sites 213 <strong>and</strong> 401 correlate withthose documented from several other locations, suchas ODP Site 690 (<strong>Bralower</strong>, 2002) <strong>and</strong> Alamedilla,southern Spain (Monechi et al., 2000). The PETM canbe subdivided into a lower part <strong>and</strong> a upper part on thebasis of nannofossil assemblages. The lower part ischaracterized by high abundances of Discoaster spp.,Ericsonia spp., <strong>and</strong> Fasciculithus spp., interpreted asindicators of warm surface waters <strong>and</strong> probably oligotrophicconditions (Wei <strong>and</strong> Wise, 1990; Aubry,1992; Kelly et al., 1996; <strong>Bralower</strong>, 2002). The upperpart shows an increase in abundance of Toweius spp.<strong>and</strong> Zygrhablithus bijugatus, which likely reflectsmore eutrophic <strong>and</strong> cooler conditions.The major nannofloral changes at DSDP Site 213seem to be strongly affected by diagenesis. Theincrease in abundance of genera most resistant todissolution, such as Discoaster, Ericsonia, <strong>and</strong> Fasciculithus,inversely correlates with the nannofossilspecies richness at Site 213.The appearance of asymmetrical Discoaster <strong>and</strong>Rhomboaster species might indicate the development<strong>and</strong> availability of new ecological niches, resultingfrom major palaeoceanographic changes during thePETM (<strong>Bralower</strong>, 2002). The last occurrence ofOctolithus multiplus might be a reliable bioevent atnorthern intermediate <strong>and</strong> high latitudes.AcknowledgementsWe gratefully acknowledge K. von Salis, J. Young,J. Lees, <strong>and</strong> an anonymous reviewer for criticalcomments that helped us improve the manuscript.Many thanks to I. Premoli Silva, E. Erba, I. Raffi, J.Backman, <strong>and</strong> G. Dickens for thoughtful discussions.Samples were provided by the Ocean DrillingProgram, <strong>and</strong> we thank the curatorial staff for their

F. <strong>Tremolada</strong>, T.J. <strong>Bralower</strong> / Marine Micropaleontology 52 (<strong>2004</strong>) 107–116 115help. This work was funded by Cofin 2001 to I.Premoli Silva, NSF EAR-9814604 <strong>and</strong> OCE-0084032(to T.J. <strong>Bralower</strong>).ReferencesAubry, M.-P., 1984. H<strong>and</strong>book of Cenozoic Calcareous Nannoplankton:Book 1. Ortholithae (Discoasters). MicropaleontologyPress, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY.266 pp.Aubry, M.-P., 1988. H<strong>and</strong>book of Cenozoic Calcareous Nannoplankton:Book 2. Ortholithae (Holococcoliths, Ceratoliths,Ortholiths <strong>and</strong> Others). Micropaleontology Press, AmericanMuseum of Natural History, New York, NY. 279 pp.Aubry, M.-P., 1989. H<strong>and</strong>book of Cenozoic Calcareous Nannoplankton:Book 3. Ortholithae (Pentaliths, <strong>and</strong> Others), Heliolithae(Fasciculiths, Sphenoliths <strong>and</strong> Others). Micropaleontology Press,American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY. 279 pp.Aubry, M.-P., 1990. H<strong>and</strong>book of Cenozoic Calcareous Nannoplankton:Book 4. Heliolithae (Helicoliths, Cribriliths, Lopadoliths<strong>and</strong> Others) Micropaleontology Press, American Museumof Natural History, New York, NY 381 pp..Aubry, M.-P., 1992. Late Paleogene nannoplankton evolution: atale of climatic deterioration. In: Prothero, D.R., Berggren,W.A. (Eds.), Eocene–Oligocene Climatic <strong>and</strong> Biotic Evolution.Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ, pp. 272–309.Aubry, M.-P., 1998. Early Paleogene calcareous nannoplanktonevolution: a tale of climatic amelioration. In: Aubry, M.-P.,Lucas, S., Berggren, W.A. (Eds.), Late Paleocene <strong>and</strong> EarlyEocene Climatic <strong>and</strong> Biotic Evolution. Columbia Univ. Press,New York, pp. 158–203.Backman, J., 1986. Late Paleocene to middle Eocene calcareousnannofossil biochronology from the shatsky rise WalvisRidge <strong>and</strong> Italy. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.57, 43–59.Bains, S., Corfield, R.M., Norris, R.D., 1999. Mechanisms ofclimate warming at the end of the Paleocene. Science 285,724–727.Bains, S., Norris, R.D., Corfield, R.M., Faul, K.L., 2000. Terminationof global warmth at the Palaeocene/Eocene boundarythrough productivity feedback. Nature 407, 171–174.Bolle, M.P., Pardo, A., Hinrichs, K.U., Adatte, T., von Salis, K.,Burns, S., Keller, G., Muzylev, N., 2000. The Paleocene–Eocenetransition in the marginal northeastern Tethys (Kazakhstan<strong>and</strong> Uzbekistan). Int. J. Earth Sci. 89, 390–414.<strong>Bralower</strong>, T.J., 2002. Evidence of surface water oligotrophy duringthe Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum: nannofossil assemblagedata from Ocean Drilling Program Site 690 Maud Rise,Weddell Sea. Paleoceanography 17, 1–13.<strong>Bralower</strong>, T.J., Mutterlose, J., 1995. Calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphyof ODP Site 865, Allison Guyot, Central PacificOcean: a tropical Paleogene reference section. In: Winterer,E.L., Sager, W.W., Firth, J.V. (Eds.), Proceedings of the OceanDrilling Program. Scientific Results, vol. 143, pp. 31–72.<strong>Bralower</strong>, T.J., Zachos, J.C., Thomas, E., Parrow, M., Paull, C.K.,Kelly, D.C., Premoli Silva, I., Sliter, W.V., Lohmann, K.C.,1995. Late Paleocene to Eocene paleoceanography of the equatorialPacific Ocean: stable isotopes recorded at ODP Site 865Allison Guyot. Paleoceanography 10, 841–865.<strong>Bralower</strong>, T.J., Thomas, D.J., Zachos, J.C., Hirschmann, M.M., Röhl,U., Sigurdsson, H., Thomas, E., Whitney, D.L., 1997. High-resolutionrecords of the late Paleocene thermal maximum <strong>and</strong> circum-Caribbeanvolcanism: is there a causal link? Geology 25,963–967.Clyde, W.C., Gingerich, P.D., 1998. Mammalian community responseto the latest Paleocene thermal maximum: an isotaphonomicstudy in the northern Bighorn Basin Wyoming. Geology26, 1011 – 1014.Cramer, B., Miller, K.G., Aubry, M.-P., Olsson, R.K., Wright, J.D.,Kent, D.V., Browning, J.V., 2000. The Bass River Section: anexceptional record of the LPTM event in a neritic setting. Bull.Geol. Soc. Fr. 170, 883–897.Crouch, E.M., Heilmann-Clausen, C., Brinkhuis, H., Morgans,H.E.G., Rogers, K.M., Egger, H., Schmitz, B., 2001. Globaldinoflagellate event associated with the late Paleocene thermalmaximum. Geology 29, 315–318.Dickens, G.R., O’Neil, J.R., Rea, D.K., Owen, R.M., 1995. Dissociationof oceanic methane hydrate as a cause of the carbonisotope excursion at the end of the Paleocene. Paleoceanography10, 965–971.Dickens, G.R., Castillo, M.M., Walker, J.G.C., 1997. A blast of gasin the latest Paleocene: simulating first-order effects of massivedissociation of oceanic methane hydrate. Geology 25, 259–262.Dickens, G.R., Fewless, T., Thomas, E., <strong>Bralower</strong>, T.J., 2003. Excessbarite accumulation during the Paleocene/Eocene thermalmaximum: massive input of dissolved barium from seafloor gashydrate reservoirs. In: Wing, S.L., Gingerich, P.D., Schmitz, B.,Thomas, E. (Eds.), Causes <strong>and</strong> Consequences of Globally WarmClimates in the Early Paleogene. Geological Society of AmericaSpecial Publication, vol. 369, pp. 11–23.Eldholm, O., Thomas, E., 1993. Environmental impact of volcanicmargin formation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 117, 319–329.Hallock, P., Premoli Silva, I., Boersma, A., 1991. Similaritiesbetween planktonic <strong>and</strong> larger foraminiferal evolutionarytrends through paleoceanographic changes. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol.Palaeoecol. 83, 49–64.Haq, B.U., Lohmann, G.P., 1976. Early Cenozoic calcareous nannoplanktonbiogeography of the Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Micropaleontol.1, 119–194.Haq, B.U., Premoli Silva, I., Lohmann, G.P., 1977. Calcareousplankton paleobiogeographic evidence for major climatic fluctuationsin the Early Cenozoic Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res.82, 3876–3961.Kahn, A., Aubry, M.-P., this volume. Provincialism associated withthe Paleocene/Eocene Thermal Maximum: temporal constraint.Mar. Micropaleontol. Spec. Issue.Kaiho, K., Arinobu, T., Ishiwatari, R., Morgans, H., Okada, H.,Takeda, N., Tazaki, N., Zhou, G., Kajiwara, Y., Matsumoto,R., Hirai, A., Niitsuma, N., Wada, H., 1996. Latest Paleocenebenthic foraminiferal extinction <strong>and</strong> environmental changes atTawanui New Zeal<strong>and</strong>. Paleoceanography 11, 447–465.