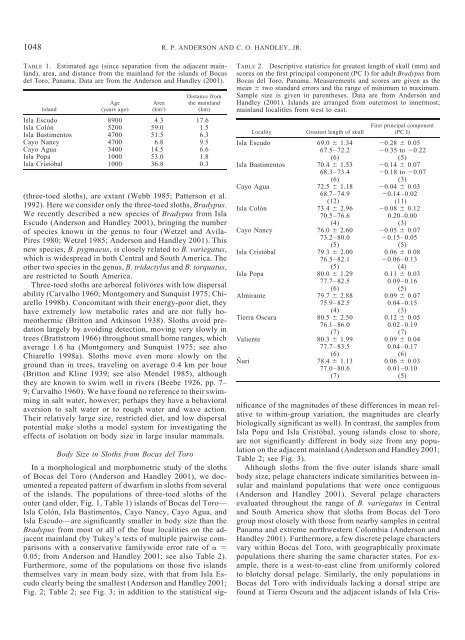

1048 R. P. ANDERSON AND C. O. HANDLEY, JR.TABLE 1. Estimated age (since separation from the adjacent mainland),area, and distance from the mainland for the islands of Bocasdel Toro, Panama. Data are from the Anderson and Handley (2001).IslandIsla EscudoIsla ColónIsla BastimentosCayo NancyCayo AguaIsla PopaIsla CristóbalAge(years ago)8900520047004700340010001000Area(km 2 )4.359.051.56.814.553.036.8Distance fromthe mainland(km)17.61.56.39.56.61.80.3(three-toed sloths), are extant (Webb 1985; Patterson et al.1992). Here we consider only the three-toed sloths, Bradypus.We recently described a new species of Bradypus from IslaEscudo (Anderson and Handley 2001), bringing the numberof species known in the genus to four (Wetzel and Avila-Pires 1980; Wetzel 1985; Anderson and Handley 2001). Thisnew species, B. pygmaeus, is closely related to B. variegatus,which is widespread in both Central and South America. Theother two species in the genus, B. tridactylus and B. torquatus,are restricted to South America.Three-toed sloths are arboreal folivores with low dispersalability (Carvalho 1960; Montgomery and Sunquist 1975; Chiarello1998b). Concomitant with their energy-poor diet, theyhave extremely low metabolic rates and are not fully homeothermic(Britton and Atkinson 1938). Sloths avoid predationlargely by avoiding detection, moving very slowly intrees (Brattstrom 1966) throughout small home ranges, whichaverage 1.6 ha (Montgomery and Sunquist 1975; see alsoChiarello 1998a). Sloths move even more slowly on theground than in trees, traveling on average 0.4 km per hour(Britton and Kline 1939; see also Mendel 1985), althoughthey are known to swim well in rivers (Beebe 1926, pp. 7–9; Carvalho 1960). We have found no reference to their swimmingin salt water, however; perhaps they have a behavioralaversion to salt water or to rough water and wave action.Their relatively large size, restricted diet, and low dispersalpotential make sloths a model system for investigating theeffects of isolation on body size in large insular mammals.TABLE 2. Descriptive statistics for greatest length of skull (mm) andscores on the first principal component (PC I) for adult Bradypus fromBocas del Toro, Panama. Measurements and scores are given as themean two standard errors and the range of minimum to maximum.Sample size is given in parentheses. Data are from Anderson andHandley (2001). Islands are arranged from outermost to innermost;mainland localities from west to east.LocalityIsla EscudoIsla BastimentosCayo AguaIsla ColónCayo NancyIsla CristóbalIsla PopaAlmiranteTierra OscuraValienteÑuriGreatest length of skull69.0 1.3467.5–72.2(6)70.4 1.5368.3–73.4(6)72.5 1.1868.7–74.9(12)73.4 2.9670.5–76.6(4)76.0 2.6073.2–80.0(5)79.3 2.0076.5–82.1(5)80.0 1.2977.7–82.5(6)79.7 2.8875.9–82.5(4)80.5 2.5076.1–86.0(7)80.3 1.9977.7–83.5(6)78.4 1.1377.0–80.6(7)First principal component(PC I)0.28 0.050.35 to 0.22(5)0.14 0.070.18 to 0.07(3)0.04 0.030.14–0.02(11)0.08 0.120.20–0.00(3)0.05 0.070.15–0.05(5)0.06 0.080.06–0.13(4)0.11 0.030.09–0.16(5)0.09 0.070.04–0.15(3)0.12 0.050.02–0.19(7)0.09 0.040.04–0.17(6)0.06 0.030.01–0.10(5)Body Size in Sloths from Bocas del ToroIn a morphological and morphometric study of the slothsof Bocas del Toro (Anderson and Handley 2001), we documenteda repeated pattern of dwarfism in sloths from severalof the islands. The populations of three-toed sloths of theouter (and older, Fig. 1, Table 1) islands of Bocas del Toro—Isla Colón, Isla Bastimentos, Cayo Nancy, Cayo Agua, andIsla Escudo—are significantly smaller in body size than theBradypus from most or all of the four localities on the adjacentmainland (by Tukey’s tests of multiple pairwise comparisonswith a conservative familywide error rate of 0.05; from Anderson and Handley 2001; see also Table 2).Furthermore, some of the populations on those five islandsthemselves vary in mean body size, with that from Isla Escudoclearly being the smallest (Anderson and Handley 2001;Fig. 2; Table 2; see Fig. 3; in addition to the statistical significanceof the magnitudes of these differences in mean relativeto within-group variation, the magnitudes are clearlybiologically significant as well). In contrast, the samples fromIsla Popa and Isla Cristóbal, young islands close to shore,are not significantly different in body size from any populationon the adjacent mainland (Anderson and Handley 2001;Table 2; see Fig. 3).Although sloths from the five outer islands share smallbody size, pelage characters indicate similarities between insularand mainland populations that were once contiguous(Anderson and Handley 2001). Several pelage charactersevaluated throughout the range of B. variegatus in Centraland South America show that sloths from Bocas del Torogroup most closely with those from nearby samples in centralPanama and extreme northwestern Colombia (Anderson andHandley 2001). Furthermore, a few discrete pelage charactersvary within Bocas del Toro, with geographically proximatepopulations there sharing the same character states. For example,there is a west-to-east cline from uniformly coloredto blotchy dorsal pelage. Similarly, the only populations inBocas del Toro with individuals lacking a dorsal stripe arefound at Tierra Oscura and the adjacent islands of Isla Cris-

DWARFISM IN INSULAR <strong>SLOTH</strong>S1049Cayo Nancy together (they separated from the mainland asa unit and only recently separated from each other; see Fig.1). Based on several unique cranial features (including someindicative of a divergent pattern of cranial circulation) andextremely small body size (well out of the variation foundanywhere in the range of B. variegatus), Anderson and Handley(2001) considered that the population on Isla Escudohas evolved to represent a distinct species, B. pygmaeus, butthat the sloths of other islands remain conspecific with B.variegatus, despite their moderate dwarfism. In any case, allinsular three-toed sloths in Bocas del Toro are very closelyrelated to populations of B. variegatus from the mainland ofPanama (see Anderson and Handley 2001 and above). L. E.Olson and R. P. Anderson (unpubl. data) have begun DNAsequencing of part of the mitochondrial genome to elucidatethe genetic relationships among populations of Bradypus inBocas del Toro (after Brooks and McLennan 1991; Avise1994; Matocq et al. 2000). Here, we test several biogeographichypotheses based on morphological data and physicalcharacteristics of the islands and compare the results withtheoretical and empirical values from other evolutionary studies.MATERIALS AND METHODSFIG. 2. Skulls of Bradypus variegatus from the Península Valienteon the mainland of Bocas del Toro (left) and Bradypus pygmaeusfrom Isla Escudo (right) showing the degree of size divergence ofthe sloth on Isla Escudo.tóbal, Isla Popa, and Cayo Nancy (for other examples, seeAnderson and Handley 2001).This pattern of similar pelage traits being present in geographicallyproximate populations (without regard to whetherthey are mainland or insular) lies in stark contrast to thestriking differences in body size between most insular populationsand the nearest respective mainland samples. Thefew cranial characters common to the small sloths on variousislands are all gracile traits associated with size reductionand ontogenetic truncation (e.g., thin zygomatic arches,weakly developed temporal crests). In fact, many cranialtraits of adult individuals of the small insular sloths mimicthose of immature individuals from the adjacent mainland(Anderson and Handley 2001), suggesting an evolutionarysyndrome often described as or attributed to paedogenesis(Reilly et al. 1997). In contrast, the pelage traits provide dataindependent of size reduction, which is especially predisposedto convergence (Roth 1992). Because of the extremedifferences in body size between mainland and insular samples,Anderson and Handley (2001) suggested that the distributionof pelage traits did not represent recent gene flow(via dispersal), but rather the relictual manifestation of previouslycontinuous geographic variation that was subdividedinto isolated populations when the islands formed.This interpretation suggests that populations of Bradypusmay have evolved smaller size four times subsequent to islandformation in Bocas del Toro: independently on Isla Escudo,Isla Colón, and Cayo Agua (each of which formedseparately) and once on the superisland Isla Bastimentos–RegressionsHypotheses based on physical characteristics of the islandsIsland area, distance from the mainland, and age representthe major physical variables potentially affecting evolutionin insular mammals. Heaney (1978) showed that body sizein tri-colored squirrels (Callosciurus prevosti) was related toisland area (presumably because intra- and interspecific competitiverelationships vary with island area and faunal richness,which is a function of area). Thus, in an archipelagowith islands varying greatly in area, optimal body size maynot be constant among all islands. In contrast, for groups ofislands with generally similar areas and selective environments(related to community composition and resource availability)for a particular taxon, island area is not expected tobe related to body size (see also Adler and Levins 1994).Second, distance from the mainland is predicted to affectimmigration rates, especially for more vagile taxa (MacArthurand Wilson 1967). Barring differences in ocean currents,prevailing winds, or opportunities for rafting (such as theoutlet of a major river) among islands of an archipelago,immigration rates for a particular taxon should be a functionof distance. Thus, for taxa and systems with appreciable immigrationrates, distance from the mainland will influencerates of morphological evolution by differentially diluting insitu evolution on closer islands with colonists from the mainland.In contrast, where immigration is minimal or nonexistent(such as island archipelagos outside the dispersal potentialof the species), distance would not be related to bodysize.Finally, when directional selection is still occurring on aninsular population, the population has not yet reached itsoptimal body size (evolutionary equilibrium). In such cases,islands of various ages present in the archipelago should showa relationship between body size and island age, with the

- Page 1 and 2: EMERGENCY PETITION TO LIST THEPYGMY

- Page 3 and 4: NOTICE OF PETITIONAnimal Welfare In

- Page 5 and 6: I. NATURAL HISTORY AND STATUS OF TH

- Page 7 and 8: known to occur, is estimated to be

- Page 9 and 10: 3. Population Trend and Extinction

- Page 11 and 12: An emergency ESA listing of the pyg

- Page 13 and 14: If not immediately protected under

- Page 15 and 16: very small island off the coast of

- Page 17 and 18: LITERATURE CITEDAnderson RP and Han

- Page 19 and 20: Evolution, 56(5), 2002, pp. 1045-10

- Page 21: DWARFISM IN INSULAR SLOTHS1047FIG.

- Page 25 and 26: DWARFISM IN INSULAR SLOTHS1051There

- Page 27 and 28: DWARFISM IN INSULAR SLOTHS1053showe

- Page 29 and 30: DWARFISM IN INSULAR SLOTHS1055shoul

- Page 31 and 32: DWARFISM IN INSULAR SLOTHS1057of th

- Page 33 and 34: IB4/inPROCEEDINGS oi TilBTDLOGICALS

- Page 35 and 36: MAT (J 200 j } ) PROCEEDINGS OF THE

- Page 38 and 39: PROCEEDINGS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIE

- Page 40 and 41: —PROCEEDINGS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SO

- Page 42 and 43: PROCEEDINGS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIE

- Page 44 and 45: variegatus.Creteiationsabbrevharact

- Page 47 and 48: 1 1IIIIIIIIII',I':IIT•I'I'VOLUME

- Page 49 and 50: VOLUME 1 14, NUMBER 1 15Colon, and

- Page 51 and 52: —VOLUME 1 14, NUMBER 1 17Table 4.

- Page 53 and 54: VOLUME 1 14, NUMBER 1 19Table 5.—

- Page 55 and 56: —VOLUME 114. NUMBER 1 2185°Brady

- Page 57 and 58: VOLUME 114, NUMBER 1 23Bradypus var

- Page 59 and 60: —VOLUME 1 14, NUMBER 1 25of B. va

- Page 61 and 62: Observations on the Endemic Pygmy T

- Page 63 and 64: Observations of Bradypus pygmaeusTa

- Page 65 and 66: 2013.1Login | FAQ | Contact | Terms

- Page 67 and 68: The 2010 Sloth Red List AssessmentA

- Page 69 and 70: 65Number of Species43210TaxonomyPop

- Page 71 and 72: Figure 3. Bradypus pygmaeus. Based

- Page 73 and 74:

Park), among other areas, although

- Page 75 and 76:

Bradypus tridactylusLeast Concern (

- Page 77 and 78:

Bradypus variegatusLeast Concern (L

- Page 79 and 80:

Figure 6. Bradypus variegatus. Base

- Page 81 and 82:

Figure 7. Choloepus didactylus. Bas

- Page 83 and 84:

as well as in secondary forest, but

- Page 85 and 86:

Acknowledgements: This assessment w

- Page 87 and 88:

perezoso de dos uñas (Choloepus ho

- Page 89 and 90:

2 MAMMALIAN SPECIES 812—Bradypus

- Page 91:

4 MAMMALIAN SPECIES 812—Bradypus

- Page 109 and 110:

J Etholtemporal frequency of vocali

- Page 111 and 112:

J EtholTable 1 Inferred period (thi

- Page 113 and 114:

J EtholB. variegatus males seem to

- Page 115 and 116:

http://news.mongabay.com/2013/0920-

- Page 117 and 118:

Crates with pygmy sloths destined f

- Page 119 and 120:

LEFT: Pygmy sloth in a box back on

- Page 121 and 122:

elevant stakeholders. A serious con

- Page 123 and 124:

night amidst violent social unrest,

- Page 125 and 126:

How Did Dallas Aquarium Almost Get

- Page 127:

three-toed sloth becomes a CITES II

- Page 132 and 133:

Although Aviarios del Caribe claims

- Page 134 and 135:

Ms. Cliffe cite hunting pressure fr

- Page 136 and 137:

work being conducted by our interna