40128 Gems and Jewellery Mag.indd - Greenaway Mosaics

40128 Gems and Jewellery Mag.indd - Greenaway Mosaics

40128 Gems and Jewellery Mag.indd - Greenaway Mosaics

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

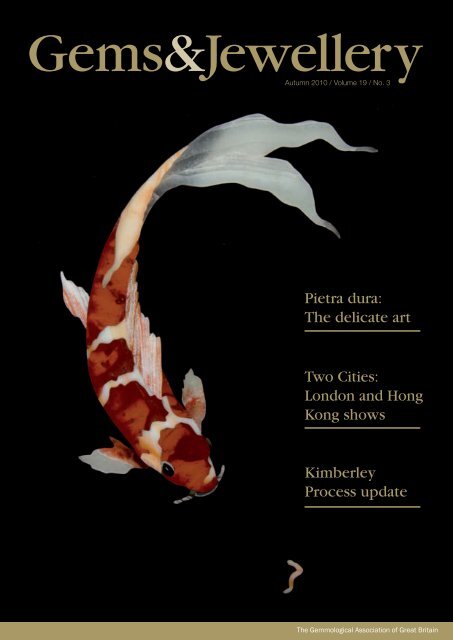

<strong>Gems</strong>&<strong>Jewellery</strong>Autumn 2010 / Volume 19 / No. 3Pietra dura:The delicate artTwo Cities:London <strong>and</strong> HongKong showsKimberleyProcess updateThe Gemmological Association of Great Britain

<strong>Gems</strong>&<strong>Jewellery</strong> / Autumn 2010 / Volume 19 / No. 3Gem-A <strong>Gems</strong> <strong>and</strong> Calendar MineralsThe delicate artPietra dura, the ancient art form also known as 'Florentine mosaic', is still producedby traditional methods in rural Northamptonshire.Koi carp plaque by Thomas <strong>Greenaway</strong>. Photo ©<strong>Greenaway</strong> <strong>Mosaics</strong> LLP.Almost every traveller to Florence in thelate nineteenth century returned with asouvenir in the form of a piece of furniture,jewellery or other small ornament decoratedwith a form of mosaic commonly termed‘Florentine mosaic’. It is often referred to as‘commesso’ although strictly speaking thisrefers to pietra dura (literally ‘hard stone’)pieces that are assembled like a jigsawpuzzle, rather than intarsia which is pietradura where pieces of stones are inserted intocarefully shaped holes in the backgroundmaterial. This extraordinary art involvesthe creation of designs — animals, figures,fish, geometric patterns — in minute piecesof precisely-shaped coloured stone inlaidinto a backing. The coloured stones includejasper, lapis lazuli, agate, chalcedony, raremarble <strong>and</strong> (nowadays especially) malachite.The surround is most often black Belgianmarble from a quarry south of Brussels,although pure black is now rare, <strong>and</strong> thebacking material is slate. The technique canbe traced back to Byzantine times <strong>and</strong> thereare superb Renaissance examples, but froma jewellery point of view the heyday wasin Victorian times, with a huge number ofexamples being produced, although not allwith exemplary skill.Among the h<strong>and</strong>ful of modern artistsusing this technique is Thomas <strong>Greenaway</strong>,of <strong>Greenaway</strong> <strong>Mosaics</strong> in Northamptonshire,whose inlaid plaque depicting a koi carp(pictured left <strong>and</strong> front cover) recently wonthe silver prize in the Lapidary section of2010 Craftsmanship <strong>and</strong> Design Awards runby the Goldsmiths’ Craft <strong>and</strong> Design Council.The materials <strong>and</strong> technique used in the latenineteenth century are well documented.*Thomas <strong>Greenaway</strong> was initially trained inwoodworking at the Chippendale Schoolof Furniture, Design <strong>and</strong> Restoration inScotl<strong>and</strong>. On a visit to Italy he discoveredthe Opificio in Florence <strong>and</strong> was intriguedby the pietra dura work he saw there, <strong>and</strong>its relationship to the marquetry work thathe had found so interesting in furniture.Studying at the Opificio was not possible,but one craftsman whom he refers to as ‘anold maestro’ took him in as an apprentice.He later moved on to another workshop,spending in all three <strong>and</strong> a half years inItaly before returning to Britain to establishhis own workshop. You can see more of hiswork at www.greenawaymosaics.comA Victorian pietra dura brooch. Photo © MarcusMcCallum.It is thus interesting to talk with Thomas <strong>and</strong>see how the modern approach compareswith that of some 120 years ago.Thomas notes that many of the oldtechniques are still used by traditionalmosaicists like himself. However stones arePage 16

<strong>Gems</strong>&<strong>Jewellery</strong> / Autumn 2010 / Volume 19 / No. 3<strong>Gems</strong> Gem-A <strong>and</strong> Calendar Mineralsnow cut into slices with circular, diamondimpregnatedwheels, rather than the ‘thinblades of iron or copper’ used with emery asan abrasive. With the circular saw cooling isrequired, <strong>and</strong> Thomas uses water with thesofter stones <strong>and</strong> oil for the harder ones. Forcutting the thin slices — traditionally about2.5–3 mm thick — into the intricate shapes,Thomas still uses a traditional chestnutbow saw (‘archetto’) with iron wire, althoughhe also employs a rotary blade with waterfor larger pieces — much quicker than thearchetto. Today moistened carborundumpowder (silicon carbide, first introduced in1891) has replaced the emery used in thepast for sawing <strong>and</strong> levelling the backs ofthe pieces. The variously shaped openings inthe surrounding black marble are still begunwith holes through which the iron wire bladecan be threaded, but today electric powerdrills have generally replaced the older h<strong>and</strong>operated drills.The backings, now as then, are slate,although these are ground flat with a lappingmachine nowadays rather than with the olderiron plates with wooden h<strong>and</strong>les. Similarlythe filing of the shapes to ensure a precisefit is now carried out with diamond needlefiles. The final polish is still a critical process<strong>and</strong> the finest emery powder is used. Thetraditional adhesive was pece greca, amixture of beeswax <strong>and</strong> mastic, with heatbeing used to bind the parts <strong>and</strong> care takento use no more cement than was necessary.With use of this mixture of beeswax <strong>and</strong>mastic resin later exposure to heat c<strong>and</strong>isplace the inlays, <strong>and</strong> so some workersnow use more modern adhesives.Thomas notes that the greatest changesince the late nineteenth century hasprobably been in the cost of labour <strong>and</strong>materials. He says: “Sadly many Florentinemosaicists are going out of business <strong>and</strong> Inow know of only about 17 small firms stillin production, many of whom are strugglingwith less than five employees. Rather than1000 involved in the trade in its heyday, Iexpect there are now about 50, <strong>and</strong> thereis a great absence of youth.” He also notesthat nowadays all the processes, from designto finishing, are usually done by one personrather than by a number of specialists,aealthough the market still relies on thecommissions of the very wealthy.Via degli Alfani 78, the home of theOpificio delle Pietre Dure, had its origins inthe Court workshop set up by the Medicisin 1588. Today the Opificio houses anfgPietra dura production. (a) A chestnut bow saw is used for cutting. (b) Paper templates are stuckdown to a selected area of the stone. (c) Cutting around the template at a 30° angle. (d) Gluing thepieces together. (e) Drilling holes to thread the iron wire through. (f) Sawing the Belgian black marble.(g) Filing the aperture to fit the pieces in to. (h) Fitting the pieces without any gap.Photos © <strong>Greenaway</strong> <strong>Mosaics</strong> LLP.bcdhdinteresting pietra dura museum <strong>and</strong> hasother departments carrying out restorationwork in many different materials.Jack Ogden* ‘How Florentine <strong>Mosaics</strong> are made.’ PallMall Gazette, September 1889.Page 17