Content - From Malan tot Mbeki

Content - From Malan tot Mbeki

Content - From Malan tot Mbeki

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

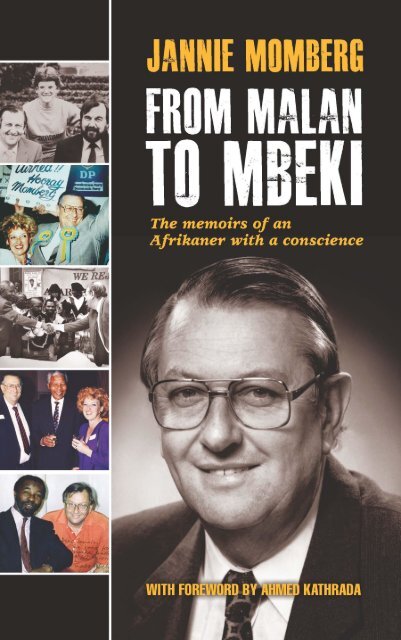

Benedic Bookswww.benedic.netThe memoirs of anAfrikaner with a conscienceByJannie MombergForeword byAhmed Kathrada

Published by Benedic BooksAddress: PO Box 5646, Helderview, 7135, South AfricaEmail:info@benedic.netWebsite: www.benedic.netAll rights reserved. 2011No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by anyelectronic or mechanical means, including photocopying and recording, or by anyother information storage or retrieval system, without the written permission of thepublisher.All photographs are from the private collection of the Momberg-family, unless otherwisestated.First print 2011ISBN: 978-0-9814408-8-0Cover design by Xavier Nagel Agencies.Editing by Maggie Follett.Index, design and typesetting by Benedic Books.Printed and bound by: SunMEDIA, Stellenbosch.

<strong>Content</strong>Foreword ........................................................................................................ iChapters1. EARLY YEARS ..................................................................................... 12. ZOLA BUDD AND MY INVOLVEMENT WITH SPORTADMINISTRATION .......................................................................... 173. HELDERBERG ................................................................................... 254. THE INDEPENDENT PARTY AND THE FORMING OFTHE DEMOCRATIC PARTY ........................................................... 415. MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT .......................................................... 506. TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA ........................................................... 767. JOINING THE ANC .......................................................................... 798. MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT IN A DEMOCRATICNON-RACIAL SOUTH AFRICA .................................................. 1209. AMBASSADOR ................................................................................ 15510. IN CONCLUSION......... .................................................................. 212AddendaSpeeches in Parliament“I am sorry...” ................................................................................... 213“I crossed my Rubicon...” ............................................................... 217Letters“I can still call Jan Hendrik Momberg my friend. What aprivilege!” ......................................................................................... 221“In solemn memory of this great son of our people” ......................... 225Index .......................................................................................................... 227

“Dear Comrade Kathy” began the email I received last Decemberfrom Jannie Momberg. These three words symbolised how far thisman had travelled in his 72 years. <strong>From</strong> having been raised in astaunch National Party family, to joining this Apartheid Party, to hisinvolvement in liberal White politics, to finally becoming an AfricanNational Congress Member of Parliament, Jannie had come full circle.The email was short - just five lines - and being Jannie, he gotstraight to the point. He explained that he was in the final stages ofwriting a book on his “political years”, and attached a few chapters <strong>tot</strong>he email. He wanted me to write the Foreword. Again in typicalJannie style, he said: “You can write whatever you think is best. Thelength is entirely up to you, as long as it’s not too short.”This was vintage Jannie - warm, enthusiastic, direct and witty. Iagreed to meet him to discuss it, and we arranged an appointment tocoincide with my visit to Cape Town. Just days before the meeting, hetelephoned me and pleaded to be allowed to reschedule ourengagement, saying: “I have just got to see the cricket match!” Weagreed to postpone the meeting; however this was not to be. A fewdays later a phone call came. I assumed it was a confirmation of ourappointment, or another reschedule ... but it was much worse; ourdear Jannie had died! It took some time to get over the shock. At theMemorial Service, Jannie briefly lived again, through the heartfeltwords of the Dominee, Trevor Manuel, and Jannie’s sons.The Foreword stayed in my mind. Although I felt that it wouldhave been presumptuous of me to conclude that Jannie’s requestwould still hold, I strongly believed that it would be a huge loss if thestory of this outstanding son of South Africa remained unpublished.I was subsequently to discover that my doubts were unfounded,when some months later, Jannie’s widow Trienie came all the wayfrom False Bay to my place in Cape Town, to inform me that the bookwas due to be published soon, and my Foreword was required.i

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>As tempting as it is, I will not steal Jannie’s thunder and reveal anyof the fascinating or amusing anecdotes that appear in the pages ofthis frank account of his remarkable story. His was a life whichspanned political eras - from Apartheid to Democracy, and his story(as the son of an elite Afrikaner family) only serves to highlight hisextraordinary personal transition in later life.Jannie was born in 1938, in the same year that I - at the age of eight- had to be wrenched away from my mother and father to attendschool in Johannesburg, as Apartheid had decreed that an Indian boycould not be admitted to the White or Black schools in Schweizer-Reneke. My first traumatic awakening to the evils of racism tookplace at a very tender age. In later years, I vowed to use my life tooppose it however I could - a journey which led me into the YoungCommunist League, the South African Communist Party, the ANC,and ultimately to 26 years in prison - but that is another story.As I was learning about Anti-Apartheid activism, on the other sideof the country, Jannie was growing up as the son of a Hitlersupporter. He was ten years old in 1948, when the National Partywon the General election, and came to power in South Africa. Itsleaders, such as the “Architect of Apartheid” (D.F. <strong>Malan</strong>) and JohnVorster were counted amongst his family's close friends. Jannie’saccount of sharing tea with a wheelchair-bound <strong>Malan</strong> - and thepolitical advice he dispensed to the young student - makes forinteresting reading.While Jannie campaigned for South Africa to become a Republic,we in the ANC were campaigning against the All-White Republic - infact, one of the charges on which Madiba was sentenced to jail for fiveyears (in 1962) was for inciting a strike against the proclamation ofthe Republic. In 1963, Jannie had his first confrontation with theNational Party because a group of “Coloured” people had beenturned away from a symphony concert in Cape Town. During thesame year, we were charged with sabotage at the Rivonia Trial, andin June 1964, sentenced to life imprisonment.We first got to hear about Jannie Momberg at Pollsmoor Prison inthe mid-1980s, when he was Zola Budd’s manager. We had been inprison for 16 years when we were first allowed to have newspapers,and in 1985 we had television. Like the rest of the world, we got toii

Forewordhear about this barefoot runner who was good enough to race in theOlympic Games. We were probably more interested in the fact thathere was another South African breaking our sporting boycott thanthe fact that she ran without shoes, or was managed by an Afrikanerwine farmer - but for Jannie, the job of managing Zola Budd meantthat he often travelled overseas, where he saw media accounts ofwhat was really happening in South Africa. He could also read aboutthe point of view of the ANC - whereas any information about thisorganisation was banned at home.We had observed through the media that this committed NationalParty supporter had broken with the Party after a membership of 30years. He writes in his memoirs that this act was “akin to losing alimb”. His slow awakening, from 1963 onwards, had led him to aturning point in 1985. At what was to be his last NP Congress, heused this opportunity to call for the abolition of certain Apartheidlaws.He finally resigned from the National Party in 1987. In 1988 heinvolved himself in the formation of a new Party - the IndependentParty. A year later, he was one of the founders of the DemocraticParty, which was formed out of a merger between the IndependentParty and the Progressive Federal Party. Later, in 1989, he was part ofthe group of (mainly) Afrikaners who travelled to Lusaka to meet theleadership of the ANC in exile. He was enriched by his encounterswith Thabo <strong>Mbeki</strong> and Chris Hani. The visit was lauded by the Anti-Apartheid Movement and lambasted by the Regime back home.In 1990, President F.W. de Klerk unbanned the ANC and releasedMadiba from prison. This move was another turning-point in the lifeof Jannie Momberg. In 1992, he and four other Democratic Party MPs:Jan van Eck, Pierre Cronje, Rob Haswell and Dave Dalling resignedfrom the Democratic Party, and joined the ANC - making them thefirst ANC Members of Parliament in the All-White House ofAssembly.My partner, Ms Barbara Hogan (also a former political prisoner)and I had our first personal encounter with Jannie in 1993, when heand his colleagues invited us to lunch in the ParliamentaryRestaurant. This was the very first time we had crossed the portals ofthe Legislature. Jannie showed us around the building. He took usiii

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>into the House of Delegates, formed in 1983 as part of the Tri-Cameral Parliament, ostensibly to represent the Indian community.This was a toothless body - a dummy institution with no powers. Itwas with a feeling of revulsion that I witnessed adults pretending tobe equal partners amongst the rulers of the country. In reality theywere 2 nd class citizens, talking (as has been described elsewhere)through a toy telephone to deaf people at the other end.My mind went back to Pollsmoor Prison, when a Member of thisbody applied to visit me, and I informed our jailers that I refused tosee him. It was not an easy decision on my part; the man in questionwas someone with whom I had served a month’s imprisonment inDurban Central Prison during the Passive Resistance movementlaunched by the South African Indian Congress in 1946. Forty yearslater he had allied himself with individuals who were regarded ascollaborators with the Apartheid Regime.I next met Jannie in 1994, while we were campaigning for the firstnon-racial, Democratic elections in the Indian Group Area ofRoshnee, near Vereeniging. His powerful, down-to-earth speechmade a significant impact upon the people.After the ANC victory, I was elected as a Member of Parliament.Apart from what we had gathered in the media, we had absolutely noidea about running Parliament. We lacked experience - even in therunning of a little Town Council! Having had years of experience,Jannie was appointed as one of the ANC Whips. In this capacity,Jannie was especially instrumental in making us comfortable.One of his numerous tasks was to allocate seating in the House toParliamentarians, which sometimes proved to be a challenge, as thisbook reveals. Taking us around that day, however, he insisted ongiving me a seat with the Cabinet Ministers. He was relying on mediareports that I had been appointed Minister of Prisons, which was true- but he was not yet aware of the change in the situation, that hadtaken place virtually overnight. I was an ordinary MP. Jannie was avery energetic and valuable Member of Parliament who did his jobthoroughly. Whether directly or indirectly, he also trained manyothers who knew nothing about the Whippery, let alone about beingMembers of Parliament.He was a very direct person, never shy to make clear what heiv

Forewordwanted - and he was sometimes even criticised for his directness.This was the first time he had come into a situation where he wasdealing with people as equals. He had only heard the names of someof the people he was going to work with, but he got widespreadsupport from Madiba downwards.We should never underestimate the sacrifices he made by movingfrom a racially exclusive set-up, to becoming a pioneer of nonracialismin the ANC. He was one of those people who turned theirbacks on the racist Parties to join our movement in the early 90s.Moving into what was the beginning of the first Democratic nonracialANC was a very bold thing for them to do, considering wherethey had come from! The response of his own community caused himto suffer immensely. He was isolated and branded a traitor.Jannie served us well in Parliament, finally resigning in 2000 - butthis was not to be the end of his contribution. He was appointedSouth Africa’s Ambassador to Greece; a position he served withdistinction until 2006. (On a personal level, I have always regrettedthat we were never able to take up any of his kind invitations to visitthe country.)No mention of Jannie and his life would be complete withoutpaying tribute to his family. His wife “Trienie” stood by his side fromthe time they first met in 1963. They married in 1964, and she becamehis partner and most ardent supporter during some of the mostturbulent years of his life. Together they had four sons - Niels, Steyn,Jannie and Altus - and Jannie was blessed with very happy years inhis role of grandfather to five grandchildren. I have no doubt that hehas helped to instil in them an understanding of the importance ofnon-racialism and equality in every aspect of their lives.Jannie travelled a long journey through the history of South Africa -and emerged both enlightened and lightened from the loadApartheid had placed on his shoulders. He has left a legacy that canonly inspire young South Africans to do even better, as they chart thefuture together.Ahmed Kathrada28 August 2011v

CHAPTER 1I was born on the 27 th of July, 1938, into a staunchly Nationalistfamily, to whom the National Party was not just a political party, butalso a way of life. My father, Niels Petersen Momberg, was a winefarmer near Stellenbosch, with very limited academic qualifications.In spite of this, he was a highly successful businessman, who waswell regarded in the community. He married late in life, being 40years old when he wed my mother Magrietha Gertruida, a Brinkfrom Molteno in the Eastern Cape.My father was strongly against the War, and pro-German. It mustbe understood that at the time South Africa was deeply polarisedbetween those supporting Britain and those supporting Hitler. Thisled to the collapse of the Coalition Government of Smuts andHertzog, and caused bitter animosity between people. Those whosupported Germany formed an organisation called the “OssewaBrandwag” and some of the more extreme members even committedacts of sabotage, which led to my father’s resignation from theorganisation.I still remember vividly one morning in 1945 when I came into thekitchen, and noticed my father sitting with his head in his hands,crying softly. I immediately knew something was badly wrong,because I had never seen my father so upset before, and I asked mymother: “Why is Pa crying?” She hinted with her eyes that I shouldnot approach him or speak to him, and replied: “Hitler is dead.”Today, more than 65 years later, this may seem weird, but it mustbe remembered that 1945 was only 43 years after the end of theAnglo-Boer war, with all its suffering and hatred for the British. Itwas therefore not strange that a large number of Afrikaans-speaking1

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>people, in particular, were German supporters. Our ancestors hadalso come from Germany. Nobody knew of the atrocities perpetratedby Hitler and his Nazis, and most of the same people, who supportedHitler during the War, were appalled when these came to light. I wastherefore brought up in a highly politicised home, which left anindelible mark on me for the rest of my life.I was almost 10 years old in 1948, when I experienced my firstpolitical awakening, with the General election. Every “Nat” expectedthat they were going to do well, but very few thought that they couldwin. My father, who was a highly respected “pillar of thecommunity”, left the house on the morning of the elections and onlyreappeared after three days, having celebrated the unexpected Natvictory from house to house. I experienced the thrill of an election forthe first time, listening to the radio as the sound of the “toot-toottoot”warned us of another impending result. The high-points of theelection were the defeat of General Smuts by Wennie du Plessis, andPiet van der Bijl by the unknown Bredasdorp farmer, Dirkie Uys.<strong>From</strong> then on, for the rest of my life, I was hooked on politics.Because my father knew them all, I became acquainted with variousNat politicians, like Dr Daniel <strong>Malan</strong>, “Polla” Roos and Otto duPlessis.I never questioned the introduction of Apartheid, because onegrew up with it, and whatever the leaders said was “alright by me.”As a youngster aged about 12, I started accompanying my father toParliament to listen to debates, and I sat transfixed by the green seatsof the Assembly Chamber, wishing that one day I might be a Memberof Parliament myself.I matriculated in 1956, and became a Law student at StellenboschUniversity. There I threw myself wholeheartedly into politics,becoming a member of the “Nasionale Jeugbond” (the NationalParty’s Youth Wing.) I was elected to the committee and helped tofight my first election in 1958.When I was a first-year student, my father told me to take the farmlabourers to cut Dr <strong>Malan</strong>’s lawn, and prune his roses. (He hadretired as Prime Minister in 1954 and lived in Stellenbosch.) It was abeautiful July morning, and at about eleven o’clock Mrs <strong>Malan</strong>pushed the old man out in his wheelchair. I joined him for tea, and it2

Early yearswas the last conversation I ever had with him. He said to me: “Nowyoung man, tell me where you stand in politics. I have known yourfather for many years, but what about you?” I replied with theimpetuousness of youth: “I am a supporter of Hans Strijdom andwhat he stands for.” He looked sternly at me, and said in his deepvoice: “Remember if you allow the pendulum of a watch to swing toofar to the right and you release it, it will swing as far to the left. It isbetter to stay somewhere in the middle.”Dr <strong>Malan</strong> died on the 7 th of February, 1959, and I was phoned thatsame evening by oom “Baken” Smit, the local organiser of the NP. Heexplained that they wanted students to dig the grave, and that weshould report at the cemetery on Sunday the 9 th .I arrived at the cemetery with a raging hangover, having drunktoo much at a wedding the night before. There were four of us, LaurieMacfarlane, Pierre Briers, Fanie Pretorius and me. When we gotdown to work and the pickaxe said, “ping!” we immediately knewthat we were going to suffer. In February the soil is as hard asconcrete and we were in trouble. None of us had ever done this typeof work before and my head was pounding madly. I went to thehome of the official gravedigger, Andrew, and asked him: “Andrew,what do they pay you per grave?” He replied: “10 Shillings” (about R2.00), so I said to him: “If you dig that grave for us and finish it by 12o’clock, I will pay you Ten Pounds” (about R20.00.) He finished thegrave well before the time and the newspapers came to take “posed”pictures of the students “digging the grave”. We never told anybodythat we had not actually dug the grave, and that a “Coloured” haddone the work for us. At the funeral we were even thanked by theleader of the NP in the Cape, Dr Eben Donges, for our selfless act!The funeral also had a bizarre twist to it. The service took place inthe “Studente Kerk” (Students’ Church) on the afternoon of Monday,February 10 th . It was not a State Funeral, but a huge crowd turned up,including many dignitaries. The Governor-General at the time, Dr E.G.Jansen, was ill and his wife attended the funeral alone. Her official carwas parked immediately behind the hearse carrying Dr <strong>Malan</strong>’s coffin.In front of the hearse was a group of six motorcycles. At the conclusionof the service, Mrs Jansen got into her car and told the driver to leave,as she was not going to the cemetery. When the official car pulled out,3

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>the motorcyclists followed her, and the driver of the hearse thoughthe was supposed to follow them, so off they went. All his life Dr<strong>Malan</strong> had been a slow speaker and a slow mover. On his last earthlyjourney, he was carried through the streets of Stellenbosch at 90kilometres an hour! The last people were still leaving the churchwhen the coffin arrived at the burial site.My father died in 1959, when I was only 21. Although I did notknow him for very long, he had a profound impact on my life. Hewas a special person with huge compassion for the needy. After hisdeath we received numerous letters from people he had helpedfinancially to further their studies, something he never spoke about. Ithink my compassion for the plight of the disenfranchised massescame from him.I was only 21, but I had to suspend my university studies to joinmy cousin, another Jan, on the family farm “Middelvlei“. It reallyhurt me not to have completed my studies and I constantly felt thatsomething was missing. (Ten years later I went back to Universityand completed my studies. In 1970 I obtained a BA degree withHistory and Economics as my Majors.)In 1963, I sold my half-share of Middelvlei to my cousin, andbought the famous Neethlingshof Estate for the astronomical price of£103,000 (R206,000.) At the time it was such a huge amount that it settongues wagging for weeks. Dire predictions were made about meand people suggested that it was just a question of time before I wentbankrupt. The farm was relatively run-down and I had to spend a lotof money to bring it to top production. When I bought Neethlingshof,it was producing about 600 tonnes of wine. By 1975 we wereproducing about 2,000 tonnes.The house on the farm was an old Cape Dutch homestead, and aNational Monument. As I was unmarried, my mother lived with meand took care of me. At the time, the infamous “dopstelsel” (<strong>tot</strong>system) was still in full swing. Farm labourers were given wine atvarious times of the day, as part of their wages. This was nothing butan enslavement system, which caused unbelievable hardship, and ledto thousands of Coloured people becoming alcoholics. It was alsovery difficult to stop, because if you didn’t give wine to the labourers,they would simply quit and go to work for a farmer who would give4

Early yearsthem their “dop”. When I arrived at Neethlingshof the labourersreceived a <strong>tot</strong> before they started work (in summer that meant atabout five o’clock in the morning.) They then got a <strong>tot</strong> at breakfast,one at eleven, one at lunch, one at four o’clock and two <strong>tot</strong>s at the endof the day. The wine was a terrible concoction and was served in acut-off “bully beef” tin. I knew that this had to stop, but realised itwas going to be very difficult. What I did was this: every time I raisedtheir salaries, I took away one <strong>tot</strong>, starting with the pre-dawn <strong>tot</strong>. Ittook me about five years to end the dop system on Neethlingshof.(Unfortunately, this practice continued for many years on certainother farms, although I believe that by the 1980s, the Stellenboscharea was <strong>tot</strong>ally free of the <strong>tot</strong> system.) I also really tried my best toimprove the living conditions on the farm. I built new houses,installed running water as well as electricity in all homes, and tried tomake life as easy as possible for the farm workers.Shortly thereafter I became involved in National Party politics.While at university, as mentioned earlier, I had belonged to the YouthWing of the NP. After I left university, I was elected Secretary of thelocal branch. I remember when, in 1960, Prime Minister Dr HendrikVerwoerd was due to speak in Stellenbosch, and I was given the taskof going through town with a “bakkie” and a loudspeaker toadvertise the meeting. I drove up and down the streets, broadcastingthe event: “Ladies and Gentlemen, please come and listen to ourbeloved leader of the National Party and Prime Minister, Dr HendrikVerwoerd, tonight at eight o’clock in the Stellenbosch Town Hall.” AsI went past the home of Dr <strong>Malan</strong>, I got mixed up with the names andinvited the people to a public meeting to be addressed by the latepolitical leader, instead of Dr Verwoerd. I don’t know whether it wastrue or not, but I was told that Mrs <strong>Malan</strong> had been in the kitchenwhen I went past, and on hearing her husband’s name shouted out,had promptly fainted!In 1961, I was very involved in the “Yes” campaign for theReferendum regarding South Africa becoming a Republic, and wasgiven the responsibility of Postal votes. One day I was sent toJoostenberg Vlakte, to assist an old man in his nineties to vote. Hehad fought in the Anglo-Boer War in 1899. He was very frail, as wellas blind. As I sat down, he asked me: “How is General Smuts?” I had5

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>to think quickly. If I had replied that Smuts was dead, it could haveupset him, and he might not have voted, so I told him with a straightface: “He is not well, but still going strong.” The old man wassatisfied and we helped him to put his cross opposite the “Yes” box.In 1961, the guest speaker at a branch meeting was the thenDeputy Minister of Education, John Vorster, and that is how I becamefriends with the Vorster family. I was very fond of Mrs Tini Vorster,who always treated me like a son, and I also took a fancy to theirdaughter, Elsa, who was in Matric at the time. (Years later, after wehad both married, our children went to the same school inBloemfontein and Elsa was very kind to our boys.) I rememberasking Mr Vorster for an autographed picture of him, and telling himthat one day when he became Prime Minister, I would hang thephoto on my wall. In 1966, after the assassination of Dr HendrikVerwoerd, Vorster was elected Prime Minister. That evening Iphoned their home and congratulated him on his election. He askedme: “Are you going to hang up my picture now?”I started attending NP Cape Congresses in 1961 and did not missone for the next 24 years. I became good friends with most of theCape MPs as well as Ministers. I developed skills for fightingelections, which helped a lot in my later career. At that time the CapeNP organisation was very good and it taught me excellent skills. Ithink I was a “born organiser”, being involved with the Farmers’Association, Wine Route, Food and Wine Festival, athletics andcricket. These things always seemed to take priority over farming,which was my bread and butter. Let me put it bluntly - I was neverreally a farmer. I became a farmer because it was expected of me tofollow in my father’s footsteps. If I had been given a choice at thetime, I would probably have opted for a legal or academic career, butI was pushed into farming with no real skills, except for an ability toorganise. I was very lucky to have oom Gys van der Westhuizen asmy farm manager for 21 years. He was always there when I wasaway, and it was really oom Gys who turned Neethlingshof into thesuperb farm it became. We also farmed with Oriental tobacco, and oomGys was regarded as one of the best in the tobacco business. In 1973oom Gys’s son, Schalk, became the winemaker at Neethlingshof -another happy situation, as Schalk was really a very good winemaker.6

Early yearsIn 1963 I had my first confrontation with the NP. A number ofColoured people were turned away from a performance of theSymphony Orchestra in the Cape Town City Hall because, under theGroup Areas Act, they were not allowed into a “White area”. I wasvery upset and wrote my first letter to Die Burger newspaper, sayingthat what had happened was wrong and immoral. I stated in myletter that I had never heard of “skollies” in dress suits attendingsymphonic performances. As usual there were many letters attackingme, and I received no support. This, however, had an impact on mypolitical status inside the NP, and at the AGM of my branch I wasopposed as Secretary for the first time. I won the election 23 votes to15, but I was very clearly reminded that if you broke ranks, the Partywould spit you out.<strong>From</strong> that day, till I left the Party in 1987, I was continuouslyengaged in fights with the NP over certain policies with which Icould not associate myself. At no stage, however, did I contemplateresigning from the Party. I always thought that by voicing myopposition, I could help to change the Party from the inside. I alsohad a run-in with the Security Police who came to the farm after I hadwritten another letter to Die Burger, and I was solemnly warned that Imust be careful with these letters as I was “causing unrest.” I gavethem an earful and then phoned John Vorster (then Minister ofJustice), to whom I complained bitterly. He promised to look into thecase. I had no problems from the Security Police thereafter.I had two good friends, both Professors at Stellenbosch University,who had a profound influence on me. They were “Sampie”Terreblanche and Christof Hanekom, who became excellent soundingboards for me in my objections against certain aspects of NP policy.Tragically, Christof died of a heart attack in 1984, but Sampie stillplays a major role in my life today, as a close friend. He helped mewith many of my important speeches in Parliament, but we had somehuge fights, especially over Sampies’s continued membership of theBroederbond. I despised the organisation, while Sampie thought hecould help effect meaningful change as a member. We almost came toblows on one occasion, but when I resigned from the NP, Sampiefollowed me a week later.On the 14 th of November 1963, a most important event took place,7

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>which changed my life forever. We had an annual NP braai(barbecue) at Libertas outside Stellenbosch, and I met Trienie Steyn -a 21-year-old student in her final year, who came from Swellendam.It was as if something unbelievable happened to me, but I clearlyknew this was going to be my future wife. She was small and blonde,and for me the most beautiful girl I had ever met!I plucked up my courage and invited her to dinner the followingevening. After that, I was convinced that I wanted to marry this girl,but she still had to do her Teacher’s Diploma the following year and Idid not even know whether she wanted to marry me. I think wewent out for two months before I asked her. She promptly turned medown, but I had made up my mind and kept on pestering her untilshe said yes.We got engaged on the 31 st of May, 1964. I was in a hurry to getmarried because, although my mother looked after me well, it wasnot the same as having a wife on the farm with you. I took Trienieeverywhere with me to meet all my farmer friends, and it was clearthat they approved of her, so I knew I had made the right choice.Before her I had various girlfriends, but nothing very serious,except for a Rhodesian girl I met in 1960. She was only 17 and I was22, but she was beautiful and I fell head over heels in love with her.Of course, we were too young to have even considered marriage. Shecame to visit me in Stellenbosch and the stay lasted exactly threedays. She became increasingly terrified of the big farm and all thepeople on it, and I also have a sneaky suspicion that my mother putthe fear of God into her about life on the farm. Anyhow, she wentback to Bulawayo, and a few months later I went up there to visit herand her parents. To my utter horror, I discovered that she was aCatholic. It must be understood that at that time, in the bigoted DutchReformed Church, being a Catholic almost placed you in the samecategory as a non-believer. I knew marrying this Catholic girl wouldnever work, and I reluctantly broke off the relationship.Trienie and I got married in Swellendam on the 19 th of December,1964. It was a typical “Boere” (Afrikaans farmers’) wedding and the400 guests enjoyed themselves enormously. The day before, I becameinvolved in a huge fight with the church authorities, as the church inSwellendam had a policy prohibiting anybody “of Colour” from8

Early yearsattending services. I had two of my trusted farm workers with meand of course I wanted them to attend the wedding. The head of thechurch refused and I kicked up such a fuss that in the end they hadan emergency meeting of the Church Council. They finally relented,and allowed my Coloured friends to attend the service. We travelledto Port Elizabeth and boarded the Windsor Castle, which took us toDurban for our honeymoon, in a luxury cabin for which I paid R25,00per night.We started our married life in the old house on Neethlingshof,after my mother had moved to another house on the farm. We willhave been married for 46 years this year, and looking back on mycareer, I now realise the huge impact Trienie has had on it, in everypossible way. We have four sons of whom we are very proud, andfive grandchildren.As I’ve said before, I always had this burning ambition to serve in apolitical position, either in the Provincial Council or in Parliament. In1973 I got the opportunity I was looking for. The NationalDelimitation Court altered the borders of the constituencies, andadded the farming areas of Stellenbosch to the False Bayconstituency. The Member of Parliament was the formidable CabinetMember, Chris Heunis. As there was a vacancy in the ProvincialCouncil, I decided to throw my hat into the ring for the NPNomination. The election was due to take place in the first part of1974.I soon discovered that there was another candidate in the field,Dr Kerneels Roelofse, a well-known businessman from SomersetWest. He was a lot older than I, far better qualified, and also verywell known in the constituency. Somerset West had been a part ofFalse Bay for a long time, whereas I was in fact a “Johnny-comelately”in that constituency. I knew I was facing almost impossibleodds, but threw myself wholeheartedly into the canvassing process. Ithought I was doing quite well, but in late December disaster struck.I developed acute backache, which forced me to becomebedridden for a time. In desperation I went to a well-known specialistin Bellville, who operated on me and removed a small cartilage,which had become lodged between two vertebrae. Within a few days9

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>the pain had gone, and I could continue campaigning.It was also a difficult time for Trienie, who was expecting ourfourth child. Altus was born on the 13 th of January, 1974 just a fewweeks before the vote for the Nomination took place. I lost by 52votes to 21. Of course I was disappointed, because nobody likeslosing, but I was also realistic enough to know that at 36 years of age Iwas not the equal of the much older and better qualified KerneelsRoelofse. However, I did well enough for the delegates of theconstituency to take note of me, and gained valuable experience incanvassing.Kerneels became a very good MPC and the Chief Spokesperson forthe NP on Financial Matters. Sadly, however, he died of a heart attacka few years later and his promising career was cut short.One afternoon I was busy in the cellar with my wines when oomKoos Eksteen, who chaired the Districts Council of the False Bayconstituency, came to see me. He asked me whether I was availablefor the vacancy left by Kerneels’s death. I gave it some thought andthen declined. I was extremely busy with many activities, being atthe time Chairperson of the Stellenbosch Athletics Club, and about tobecome Chairperson of the Western Province Athletics Association,as well as being Secretary of the Stellenbosch Wine Route and theStellenbosch Farmers’ Association. I was still a bit hurt by my lossagainst Kerneels and did not know whether the election would beuncontested. I was really not in the mood for another gruellingcontest, with the result that oom Koos then became the MPC.As mentioned previously, I had a very good relationship withJohn Vorster. Looking back today, with hindsight, he was one of themost hard-line leaders of the NP. It was he who banned the ANC; hislaws sent the ANC leadership to jail, and in his time South Africainvaded Angola. He also became embroiled in the so-called“Muldergate“ Scandal involving Connie Mulder and Eschel Rhoodie,that later led to his own demise. Mulder and Rhoodie developed ascheme for using about R64 million from secret Defence Force funds(which were protected from Parliamentary scrutiny), to set up aclandestine operation to promote South Africa.They started The Citizen newspaper, using the Afrikaans businesstycoon, Louis Luyt, as a front. This was done to serve as a “counter-10

Early yearsvoice” to the Rand Daily Mail, which government believed to be partof the “hate South Africa campaign.” When the whole scheme wasexposed by a Select Committee of Parliament, Vorster resigned asPrime Minister and took on the ceremonial job of State President.P.W. Botha became Prime Minister and set up the ErasmusCommission of Enquiry into the “Information Scandal”. The ErasmusCommission was a ploy of Botha’s to tarnish the political careers ofhis opponents. The Commission reported that Vorster “kneweverything of the misuse of funds” and had agreed to everything.Vorster resigned as State President on the 4 th of June, 1979. Despiteeverything, I was very fond of “oom John.” He always treated mewith kindness and never gave me bad advice when asked. I wasshocked by his resignation and filled with an overwhelming feelingof sorrow, especially for Mrs Tienie Vorster.I drove to Groote Schuur - the official Residence of the StatePresident, in Cape Town. At the gate I was stopped by a guard whotold me that no visitors were allowed. I asked them to phone thehouse and say it was I at the gate. Mrs Vorster told them to let mecome up to the house. On my arrival I found her with the ReverendKobus van der Westhuizen, who was comforting her. She told methat Mr Vorster was busy with his legal team. It was obvious that shewas extremely upset by what had happened, and what the Vorsterfamily regarded as P.W. Botha’s treachery. I sat with her while Rev.Van der Westhuizen prayed for her and asked for God’s assistance inthis hour of sorrow and disappointment. I regarded it as a singularhonour to be allowed to share this very intimate moment. We had teaand then the door opened and oom John came out. Although heseemed very tired, he was pleased to see me. He was very bittertowards P.W. Botha. He said to me: “That bliksem (bastard) has nowgot what he wanted. But I tell you God does not sleep. One day P.W.will sit lonely in the Wilderness with nobody who gives two hoots forhim.” Profound, prophetic words!Oom John died on the 10 th of September, 1983, at the age of 68. Idecided to attend the funeral, flying to Port Elizabeth and thendriving to Kareedouw where he was to be buried. It was a sadoccasion for me, especially to see how few NP people were at thefuneral. When Johan Volsteedt (from Grey College) and I arrived at11

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>the church, I was amazed that we were directed to the pews wherethe family sat, whereas the Rector of Stellenbosch University (whereoom John was Chancellor) sat amongst the ordinary public. I wasreceived with great warmth by Mrs Vorster who, at the receptionafterwards, told all and sundry of the sweet potatoes I used to bringher when I was going out with Elsa.In 1981, there was another delimitation of constituencies. A newconstituency, Helderberg, was formed out of Somerset West, thefarms of Stellenbosch, a part of Brackenfell, and the suburbs ofStellenbosch south of the Eerste River. This meant that there wouldbe vacancies for a Member of Parliament as well as a member for theProvincial Council. I decided to make another attempt to get thenomination for the Provincial Council in Helderberg.The 1981 nomination contest was to be a lesson for me in howruthless Party Politics could be. I entered the race at a very earlystage, and for a long time I was the only candidate in the field. Ivisited every voting delegate and was so well received that I startedto take it for granted that I would win. I even told my athleticscommittees that I would be resigning. Piet Carinus warned me that Ishould not be complacent, as he had heard rumours that ChrisHeunis was looking for his own candidate. Piet Carinus had goodreason to be wary of Heunis, as he had been brutally shoved asidewhen a vacancy for MP arose in the Helderberg constituency. Pietwas the MPC for Stellenbosch for a number of years, and one of themost respected agricultural leaders in the Western Cape. It waslogical that he would step into the vacant Helderberg seat where hisfarms were. Without consulting Piet, Heunis decided that he wouldbe the candidate in Helderberg and that the current MPC for FalseBay, Koos Albertyn, would be the new MP in that constituency. PietCarinus was furious and never forgave Heunis.About two weeks before the nomination, I was shocked rigidwhen I heard that Jimmy Otto from Brackenfell was also in the field,canvassing for the nomination. It was not the fact that he was in thefield which astonished me (as that was his democratic right), butrather the sheer unexpectedness of his entry into the race. Jimmy andI had been good friends since the 1974 nomination contest, and I had12

Early yearsactually won that branch’s support. It immediately meant that the 15votes I had taken for granted were lost. I soon discovered that themain instigator behind Jimmy’s candidature was Chris Heunis. Chrisnever wanted a colleague who was going to stand up to him, butrather somebody who would support him regardless of what heproposed.The voting started in the branches and things were going well,although I was worried as, in both the Bottelary branch and theStellenbosch branch, I picked up a distinct feeling of “cooling off”.We met for the nomination meeting and I was fairly confident. Iwas shocked, however, when the result came out, and I had lost by 34votes to 33! Nonetheless, I made a gracious concession speech,pledging my full support to Jimmy. Trienie and I then went home tolick our wounds. She was also bitterly disappointed, as we had nevercontemplated the possibility of losing. Looking back now, it was ablessing. Over the years I became more and more worried anddisenchanted about the policies of the National Party, although atthat stage I still believed that it was better to remain within the NP,and to try and change it from the inside. However things becamesteadily worse in South Africa, and I have often wondered how Iwould have handled my reservations whilst a representative of theParty.Another issue that might have worked against me was the“Broederbond” factor. It should be clearly stated that I was never amember of the Broederbond. The name “Jan Momberg” whichappears in Hennie Serfontein’s Broederbond book is that of mycousin “Stil Jan” Momberg. Stil Jan was as close as a brother to me,but we had a different political outlook at times.Early in the 1960s, I became a member of the “Rapportryers”; thiswas the first step to becoming a member of “Die Broederbond”. TheRapportryers had a rule that if you missed three meetings in a rowwithout a valid excuse, you were automatically suspended. Iattended a few meetings, but then decided to stay away for threeconsecutive meetings, as I would not have fitted into that kind oforganisation.My biggest issue with Die Broederbond was that a group ofAfrikaners decided that some Afrikaners were “better than others”.13

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>These so-called “chosen Afrikaners” then met as a secret organisation- Die Broederbond - to make all the big political decisions of the day.Someone like me would never have been acceptable to DieBroederbond, as I was too critical; too open with my thoughts andideas, and they preferred “yes-men” (no women were allowed), andpeople who didn’t make waves.At first, I was an enthusiastic supporter of Chris Heunis’s proposalto change the Constitution, so as to provide for a “TricameralParliament” that allowed for the representation of Coloured andIndian voters. At the time, I did not understand the unbelievablestupidity and disastrous consequences of leaving Blacks out of theprocess.At the special National Party Congress, held in Bloemfontein toapprove the New Constitution, I was the only delegate who was not aCabinet Member to speak. I strongly supported the proposals andslammed the Right-wingers, who saw these as the “thin edge of thewedge” that would inevitably lead to Black majority rule. The NewConstitution was then put to the White Electorate in a Referendum,and approved with a two-thirds majority.In the mid-80s I became involved in the career of the athlete ZolaBudd, which I describe elsewhere in the book. This took me overseasfor lengthy spells, on a number of occasions. At this time, P.W. Bothahad declared a State of Emergency, and the country was virtuallyunder Martial Law. The press could not write freely, and White SouthAfricans were <strong>tot</strong>ally oblivious to the fact that things were going frombad to worse.When I went to the United Kingdom, I was able to watch BBCnews broadcasts, and read the newspapers. I discovered to myhorror that my country was burning. For the first time I saw whatwas happening in the townships, and that the ANC’s threat to makeSouth Africa ungovernable was becoming a reality.In November of 1985, I was due to attend the NP Congress of theCape Province in Port Elizabeth. I had been attending NP Congressessince 1961, and little did I know that this was to be my last. Abouttwo weeks before the Congress, I received the Agenda for themeeting, and was horrified to see that a small Northern Cape towncalled Pofadder was proposing that the application of the Group14

Early yearsAreas Act be made more stringent. All my life this had been the oneApartheid Law I abhorred most, and I immediately started work on aspeech opposing this motion. I instinctively knew that as far as mypolitical future was concerned, this was going to be a watershedmoment.At the Congress, I spoke to a few delegates who all thought I wasmad to oppose the Motion, but one delegate from Durbanville, JackieCarstens, supported me. I was extremely nervous at the start of thedebate. Chris Heunis was in the Chair, and the Deputy Minister ofLocal Government, Piet Badenhorst, was to answer the debate. Afterthe delegate from Pofadder had made his speech (in which all theusual racist arguments were repeated), I got my chance. I stated thatI had been overseas a number of times over the past year, and it wasquite clear that the whole of the Western World was waiting for asign that the South African Government was prepared to makechanges in its Domestic Policies. I said it was time to startslaughtering the “holy cows of Apartheid”, adding that if theAfrikaner needed the Group Areas Act, the Mixed Marriages Act, thePopulation Registration Act and the Separate Amenities Act topreserve itself, then the Afrikaner “deserved to go under”. I said thatI could not support the Pofadder Proposal, and pleaded for a relaxingof Apartheid measures.During my speech, P.W. Botha had been sitting at the back of thestage talking to his Private Secretary. Halfway through my speech, hegot up and moved to the main table, pushing Piet Badenhorst out ofhis chair with the words: “Ek sal hom self hanteer.” (I will deal withhim myself.) As I sat down, there was a deathly silence. Nobodycheered. I felt terribly lonely. P.W. was in a belligerent mood. Hesaid: “You can go overseas seven times seventy but I am telling youtoday, this is where I put my foot down. I will not budge.” He reallywiped the floor with me, and at the end of his speech he was given astanding ovation. I also had to participate in this, as it would havebeen political suicide not to do so. Afterwards I sat quietly in mychair, feeling <strong>tot</strong>ally drained. To be castigated by P.W. was always aharrowing experience. Someone gave me a note, which read: “DieBaas wil jou sien.” (The Boss wants to see you.)I walked onto the stage and was confronted by the Director-15

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Malan</strong> to <strong>Mbeki</strong>General of the Presidency, General Jannie Roux. He was a short,pompous guy whose only claim to fame was that he had beenmentioned in a very unflattering way by Breyten Breytenbach, in a bookon his years in jail. He asked me: “Can I help you?” I replied: “ThePresident wants to see me.” He asked: “And who are you?” I was stillvery agitated, and now this man - who had heard me make a speech just10 minutes before - had the cheek to ask who I was! I rudely pushed himaside, almost snarling at him: “If you don’t know, you will f-----g neverknow.” I went up to the President and asked: “Do you want to see me,Mr President?” He put his hand on my shoulder and said: “Jan, this isthe best speech I have ever heard in all my years at a Congress. Butplease remember, I also have my problems.” I was speechless. P.W.was almost telling me, in so many words, that he agreed with what Ihad said!The story had a very funny ending. As I mentioned, I wasinvolved in the career of Zola Budd and at the Congress, Mrs ElizeBotha (P.W.’s wife) asked me to let her have Zola’s address inLondon, as she wanted to write her a letter of encouragement. I senther the address.On the day that I made the speech in Congress, Mrs Botha was notpresent, and did not know what had occurred. During lunch I wassitting with some journalists, and the whole dining room was abuzzwith discussions about what had happened that morning at theCongress. Mrs Botha was having lunch at a table near us and as shewas leaving, she came up to me. She thanked me for the address andasked me to convey her best wishes to Zola. When she approachedmy table, a deathly silence fell over the dining room. It must havelooked to everyone as if she approved of what I had said! Thatafternoon I flew back to Cape Town and Mrs Botha was on the sameflight. She turned around to me with a smile and said: “P.W. told meyou were very naughty this morning.”After that Congress, I slowly drifted away from the NP. I don’tthink it was a deliberate thing. I sold Neethlingshof, we moved tosuburban Stellenbosch, and I lost contact with my branch. Although Istill paid my annual membership fees, I never became involved in mynew branch’s activities, so it was actually easy when I had to breakwith the NP.16

CHAPTER 2Athletics and politics have always played an important role in mylife. It was through athletics that I became involved in Zola Budd'scareer as a long distance runner - and ultimately this involvement ledme to the point where I had to drastically change my own politicaloutlook.I first got to know Zola Budd when she came to Stellenbosch as ateenage athlete, to take part in “hour meets” at Coetzenburg. She wasthe biggest star in South African Track and Field athletics at the time,and the crowds flocked to the track to see her in action.She was only 15 at the time of her first visit. Her parents did notwant her to stay with the other athletes because of her age, so sheoften stayed with us at Neethlingshof. We often teased her for hermeagre eating habits. (Two peas and a bowl of ice cream seemed tobe her favourite.)Through those visits, I also became good friends with Zola’s coach,Pieter Labuschagne. He was a teacher at Zola’s school in Bloemfontein,Sentraal High School.At the time, it became known that her family had decided toaccept an offer from The Daily Mail newspaper in London, to helparrange for Zola to obtain a British passport, so as to enable her to runin England. Zola’s father, Frank, had English parents - and Zolatherefore qualified for an “ancestral” passport through him.South Africans were, at that stage, banned from internationalcompetition, and although some South Africans on both sides of thepolitical fence weren’t happy with Zola running for Britain, mostwere happy to see a talented local youngster shining on theinternational stage.17