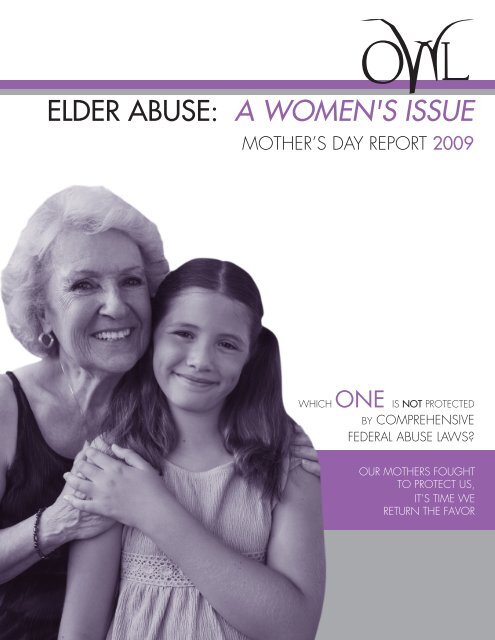

elder abuse: a women's issue - OWL-National Older Women's League

elder abuse: a women's issue - OWL-National Older Women's League

elder abuse: a women's issue - OWL-National Older Women's League

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Table of ContentsA Message From the <strong>OWL</strong> President..................................................... 2Executive Summary.............................................................................. 3Elder Abuse: A Women’s Issue............................................................... 6Ashley B. Carson, J.D., <strong>OWL</strong> Executive DirectorAge and Intimate Violence.................................................................. 13Professor Cheryl Hanna, J.D.Elder Abuse: A Women’s Issue............................................................. 14Lisa Nerenberg, MSW, MPHProtecting Your Mother from Financial Fraud and Abuse.................... 18Cindy Hounsell, J.D.Elder Justice Legislative Update........................................................... 23Robert Blancato, <strong>National</strong> Coordinator - Elder Justice CoalitionFloor Statements by Senator Hatch and Senator Kohl –Introduction of the Elder Justice Act 2009....................................... 25Medication, Abuse and Neglect: A Contemporary Dilemma............... 27Donna Wagner, Ph.D.The Role of Medication Mismanagement in Abuse and Neglect.......... 29Maura Conry, Pharm D, MSW, LCSWJoin <strong>OWL</strong>........................................................................................... 331828 L Street NW, Suite 801 • Washington, DC 20036Phone 1.800.825.3695 • Fax 202.332.2949www.owl-national.org

A Message From <strong>OWL</strong>’s PresidentHappy Mother’s Day<strong>OWL</strong> - The Voice of Midlife and <strong>Older</strong> Womencelebrates Mother’s Day as a “call for action” day toimprove the well-being of today’s older women andfuture generations of women. Our topic for the 2009Mother’s Day Report is critical to women and thosewho love them – Elder Abuse.Donna L. WagnerPresident, <strong>OWL</strong>Elder <strong>abuse</strong> is a topicthat is difficult to talkabout and frequently apart of too many women’slives. Elder <strong>abuse</strong> is a termthat encompasses a widereachingset of behaviorstowards <strong>elder</strong>s that aredesigned to diminish themand, in too many cases,physically harm them.Women are more likely tosuffer the pain and turmoilof <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> than are men.Research suggests that some women have experienced<strong>abuse</strong> throughout their lives and others only begin toexperience <strong>abuse</strong> when they have aged. In a 2006 studyof women 60 years of age and older conducted by BonnieFisher and Saundra Regan, almost half of the over 800women surveyed in a telephone survey reported they hadexperienced <strong>abuse</strong> and many had multiple exposures to<strong>abuse</strong> since turning 55. Whether the <strong>abuse</strong> was physical,emotional, psychological, or sexual, <strong>abuse</strong> was associatedwith long-term health problems for these women.In our work, <strong>OWL</strong> is a champion for social changethat matters in the lives of women and their families.We work for accessible, affordable and high-qualityhealth care, economic security, and a quality of life thatincludes the right of all persons to remain in control ofdecisions throughout their lives and the right to live freefrom exploitation and <strong>abuse</strong>. We believe it is time to end<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> and to make sure that our daughters andgranddaughters and those they love can look forward toa long life free of coercion, physical and psychologicalharm. <strong>OWL</strong> is advocating for a federal standard thatwill ensure that future.We have dedicated our Mother’s Day report to thisimportant topic and hope that you will feel as stronglyas we do that it is time to put an end to <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>and will stand with us to work for women’s dignity andindependence every day of their lives.Donna L. WagnerPresident, <strong>OWL</strong>May 2009<strong>OWL</strong> Board of DirectorsDr. Donna L. Wagner, PresidentMargaret Hellie Huyck, Vice PresidentDr. Johnetta Marshall, SecretaryLilo Hoelzel-Seipp, TreasurerEllen Bruce, President EmeritaJoan BernsteinCristina CaballeroGladys ConsidineRose Garrett-DaughetyLowell GreenCarol Hardy-FantaShirley HarlanLinette KinchenMargaret Beth NealKathie PiccagliDianna PorterKay Randolph-BackAmy ShannonSandy TimmermanSue Fryer WardAshley B. Carson, Executive Director2

Executive SummaryThe Center of Excellence on Elder Abuseand Neglect - University of California, Irvine<strong>OWL</strong>- The Voice of Midlife and <strong>Older</strong> WomenOn Mother’s Day, we remember and honor ourmothers and grandmothers. However, on this day wemust also remember older women who are not honoredor respected, but instead mistreated. These women livein fear of a harsh word, violence, money being takenfrom them or worse. Many are too frail, afraid, ashamedor sick to call for help.Yet these women, too, are members of the GreatestGeneration - the same women who enlisted in the WACsand WAVEs during WWII, answered the call to servein the factories to keep the war effort going, integratedthe buses in Montgomery, immigrated to this countryfrom all over the world, worked three jobs -- all to givetheir children chances they never had. Who are they?How many of them are victims of <strong>abuse</strong>? And what isAmerica doing to help?This report brings together experts and organizationsthat work to combat the problem of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>. Throughtheir voices, we learn about the many dimensions of andcomplexities surrounding <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, how it affectswomen in a disproportionate manner, and we seek tofind effective solutions.America’s Growing Elderly Population: In 2000,the U.S. Census Bureau counted 281.4 million peoplein the United States. Of this number; 35 million, orone out of every eight people, were age 65 and over. 1Every day, more than 6,000 Americans celebrate their65th birthdays. 2 Since 1900, the over 65 populationhas doubled three times. 3 On January 1, 2011, as babyboomers begin to celebrate their 65th birthdays, 10,000people will turn 65 every day—this will continue for 20years. By 2050, more than 20% of Americans will beover 65 years of age.The fastest growing segment of American’s populationis those 85 and up. 4 During the twentieth century, thepopulation of Americans age 85 and older grew from100,000 to 4.2 million. 5 In this age group, known asthe oldest old, women outnumber men by 2.6 to 1. 6The number of people age 100 and older increased 36%between 1990 and 2003— growing from 37,306 to50,639. Now there are more than 60,000. By 2045, thenumber of centenarians in the United States is projectedto reach 757,000. 7Women age 65 and older are still more likely than menof comparable ages to be living alone and experiencinghigher poverty rates. 8Elder Abuse: a growing, yet hidden problem: Eldermistreatment is defined as intentional actions that causeharm or create a serious risk of harm (whether or notharm is intended) to a vulnerable <strong>elder</strong> by a caregiveror other person who stands in a trust relationship to the<strong>elder</strong>. This includes failure by a caregiver to satisfy the<strong>elder</strong>’s basic needs or to protect the <strong>elder</strong> from harm. 9According to the best available estimates one to twomillion people age 65 and above are injured, exploitedor otherwise mistreated 10 Even the most conservativeestimates reveal that at least one million older Americansexperience mistreatment. Adult Protective Servicesagencies investigated 461,135 reports of <strong>abuse</strong> in 2004,representing a 15.6% increase since the previous nationalsurvey in 2000. 11 However, for every report of <strong>elder</strong>mistreatment that is made to Adult Protective Services,it is estimated that at least five cases go unreported. 12Those Who Are Abused: Female <strong>elder</strong>s are <strong>abuse</strong>dat a higher rate than males. In two-thirds of reportsto Adult Protective Services, the victim is an older ordisabled woman. The older you are, the more likely it isthat you will be <strong>abuse</strong>d. 13Those Who Abuse: In the only national study thatattempted to define the scope of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, the vastmajority of <strong>abuse</strong>rs were family members (approximately90%), most often adult children, spouses/partners andothers. 14 Family members who <strong>abuse</strong> drugs or alcohol,who have a mental/emotional illness, and who cannothandle their caregiving responsibilities, <strong>abuse</strong> at higherrates than those who do not. 153

Dementia and Elder Abuse: Research indicates thatpeople with dementia are at greater risk of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>than those without. 16 17 A recent study revealed thatclose to 50% of people with dementia experience somekind of <strong>abuse</strong>. 18 Approximately 5.1 million Americansover 65 have some kind of dementia. Close to half ofall people over 85, the fastest growing segment of ourpopulation, have Alzheimer’s disease or another kind ofdementia. By 2025, most states are expected to see anincrease in Alzheimer's prevalence. 19 Women over 90 aresignificantly more likely to have dementia than men ofthe same age. 20Chronic Illness and Abuse: In 2005, 44% of thoseage 75 years and over living in the community reportedhaving a limitation in their usual activity due to a chroniccondition. 21 Gender disparities in functional status arenotable, with more women over 65 than men havingproblems performing activities that are important forindependent functioning. 22Mistreatment in Nursing Homes and Other Long-Term Care Facilities: Over 2.8 million older Americanslive in the nation’s 64,000 licensed care facilities. 23 Justover 5% of the <strong>elder</strong>ly were in nursing homes in 1985,down to 4.6% in 1995, for an annual decline of 0.7%. 7The Long Term Care Ombudsmen reported receivingalmost 14,000 allegations of <strong>abuse</strong>, gross neglect orexploitation in 2007. 24 A 2008 study conducted by theU.S. General Accountability Office revealed that statesurveys understate problems in licensed facilities: 70%of state surveys miss at least one deficiency, and 15% ofsurveys miss actual harm and immediate jeopardy of anursing home resident. 25Impact of Elder Mistreatment: Elders whoexperienced mistreatment, even modest mistreatment,had a 300% higher risk of death when compared tothose who had not been mistreated. 26 Women whoexperienced psychological or emotional <strong>abuse</strong> (alone orwith other kinds of <strong>abuse</strong>) had significantly increasedodds of reporting joint, heart and digestive problems;depression or anxiety; and chronic pain. 27 Elder financial<strong>abuse</strong> costs older Americans more than $2.6 billion peryear. 28America’s Response to Elder Abuse - Silence Isn’tReally Golden: Current federal resources devoted tothe problem of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> are minimal. The SenateSpecial Committee on Aging estimates that less than2% of federal “<strong>abuse</strong> prevention” dollars go to <strong>elder</strong>mistreatment efforts (though <strong>elder</strong>s comprise 12% ofAmerica’s population).At the U.S. Department of Health and HumanServices (HHS):• Adult Protective Services, the front line responderto <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, does not even have a federal officeor federal standards, oversight, training, datacollection or reliable funding.• The <strong>National</strong> Institute on Aging, which leads thefederal effort on aging research, last year spentonly about $1 million (or 1/1000 th of its annual$1 billion budget) on <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> research, a smallfraction of what it spends on other <strong>issue</strong>s.• The Centers for Disease Control and Preventionlast year spent just $55,000 of its $8.8 billionannual budget (0.00062%) on <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> <strong>issue</strong>s.• Recent Government Accountability Officereports cite serious care and oversight deficienciesin facilities funded and regulated by the Centersfor Medicare and Medicaid Services, oftenresulting in <strong>abuse</strong>, neglect or even death of frail<strong>elder</strong>s. A study by Rep. Henry Waxman’s officefound <strong>abuse</strong>-related deficiencies in one third ofnursing facilities.• The Administration on Aging spends about $6million (0.5% of a $1.4 billion budget) on <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong> efforts, plus $16 million on the Long TermCare Ombudsman program.• Elder <strong>abuse</strong> is not just a health <strong>issue</strong>. It also oftenis a federal, state or local crime or a civil offense,albeit one that is rarely recognized or prosecuted.At the Department of Justice (DOJ):• The Office on Violence Against Women (OVW)spends only 1% of its funds on <strong>elder</strong>s, whocomprise 20% of the adult population but arerarely served by domestic violence programs.• The Office of Justice Programs (OJP), DOJ’sgrant-making arm, in FY 2008 spent less than $2million (less than 0.5% of its $2.3 billion 2008budget) on <strong>elder</strong> justice efforts.• Current federal <strong>elder</strong> justice efforts are sporadic4

and pursued by a handful of dedicated staffwho meet periodically, but usually juggle thoseactivities with many other duties. They requirehigh-level coordination, evaluation, focus, andsupport. There is no Office on Elder Justice; onlyan informally-created Elder Justice Initiative witha $1 million/annual budget. By contrast, OVW’sbudget ($400 million) and the Office of JuvenileJustice and Delinquency Prevention’s budget($383 million) have assured policy and programdevelopment, and sustained focus on child <strong>abuse</strong>and domestic violence for decades.The new Administration should appoint highlevelSpecial Advisors on Elder Justice at HHS andDOJ to address the long-invisible, but widespread andgrowing public health and justice system problems of<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, neglect and exploitation (<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>). TheAdministration should make the passage of the ElderJustice Act (S. 795/H.R. 2006) a priority for thisCongress.ENDNOTES1 U.S. Administration on Aging 2004,A Profile of <strong>Older</strong> Americans.2 Alliance for Aging Research 1999, Independence for <strong>Older</strong>Americans: An Investment for Our Nation’s Future.3 Demography Is Not Destiny, Revisited, RobertB. Friedland, Ph.D., and Laura Summer, M.P.H.,The Commonwealth Fund, March 2005.4 U.S. Census Bureau, Population Projections, 2008.5 Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-RelatedStatistics 2004, <strong>Older</strong> Americans6 Campion, E.W., N Engl J Med. 1994 Jun 23;330(25):1769-75.7 Administration on Aging 2004, A Profile of <strong>Older</strong> Americans8 Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics.<strong>Older</strong> Americans 2004: Key Indicators of Well-Being.Available at: http://www.agingstats.gov/chartbook2004/default.htm Accessed January 20, 2006.9 Bonnie, R. J., & Wallace, R. B. (Eds.). (2003). Eldermistreatment: Abuse, neglect and exploitation in an agingAmerica. Washington, DC: <strong>National</strong> Academies Press.10 Ibid.11 <strong>National</strong> Center on Elder Abuse, The 2004Survey of State Adult Protective Services: Abuseof Adults 60 Years of Age and <strong>Older</strong>, 2006.12 The <strong>National</strong> Elder Abuse Incidence Study, Final Report,September 1998. Prepared for the Administrationfor Children and Families and the Administrationon Aging in the U.S. Department of Health andHuman Services by the <strong>National</strong> Center on ElderAbuse at the American Public Human ServicesAssociation in collaboration with Westat, Inc.13 The <strong>National</strong> Elder Abuse Incidence Study,Final Report, September 1998.14 The <strong>National</strong> Elder Abuse Incidence Study,Final Report, September 1998.15 Schiamberg, Lawrence B. & Gans, Daphna (1999).An Ecological Framework for Contextual RiskFactors in Elder Abuse by Adult Children. Journalof Elder Abuse & Neglect, 11 (1), 79-103.16 Cooney C, Howard R, Lawlor B. Abuse of vulnerablepeople with dementia by their carers: Can we identify thosemost at risk? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21:564-71.17 VandeWeerd C, Paveza GJ. Verbal mistreatmentin older adults: A look at persons with Alzheimer’sdisease and their caregivers in the state ofFlorida. J Elder Abuse Negl 2005;17:11-30.18 Cooper, Claudia, Selwood, Amber, et al. Abuse of peoplewith dementia by family carers: representative crosssectional survey. British Medical Journal, 2009;338:b15519 Alzheimer’s Association, 2009 Alzheimer’sDisease Facts and Figure.20 University of California - Irvine (2008, July 5). WomenOver 90 More Likely To Have Dementia Than Men.ScienceDaily. Retrieved April 16, 2009, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2008/07/080702160957.htm21 <strong>National</strong> Center for Health Statistics, Health, UnitedStates, 2007, With Chartbook on Trends in theHealth of Americans, Hyattsville, MD: 2007.22 Ory, Marcia G. Women’s Health Concerns: Focuson the Aging Baby Boomers, viewed at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/523439, 2006 Medscape.23 <strong>National</strong> Ombudsman Resource Center websiteat http://www.ltcOmbudsman.org/.24 <strong>National</strong> LTC Ombudsman ResourceCenter – Complaints for FY200725 U.S. Government Accounting Office Report. NursingHomes: Federal Monitoring Surveys Demonstrate ContinuedUnderstatement of Serious Care Problems and CMSOversight Weaknesses (GAO–08-517, May 2008).26 Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, PillemerKA, Charlson ME. The mortality of <strong>elder</strong>mistreatment. JAMA. 1998; 280(5): 428-432.27 Fisher, B.S., and Regan, S.L. (2006) “The Extentand Frequency of Abuse in the Lives of <strong>Older</strong>Women and Their Relationship with HealthOutcomes.” The Gerontologist, 46:200-209.28 MetLife Mature Market Institute, Broken Trust:Elders, Family and Finances, March 2009.5

Elder Abuse: A Women’s IssueAshley B. Carson, J.D.Executive Director, <strong>OWL</strong> –The Voice of Midlife and <strong>Older</strong> WomenIn America, we all emphatically agree that everyonehas the right to live free from violence, <strong>abuse</strong>, neglectand exploitation regardless of their gender, race or age.Yet domestic and institutional <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, neglectand exploitation cause serious harm to anywhere from500,000 to 5 million individuals every year. 1 Womenmake up approximately 66% of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> victimsin the United States, and 89% of the cases of <strong>abuse</strong>occurred in a domestic setting. 2 <strong>OWL</strong> believes that the<strong>abuse</strong> of older women is an under-recognized crisis, acrisis that is exacerbated by the stigma related to <strong>abuse</strong>and the many types of oppression that continue to affectwomen during their lives, making them more vulnerableto the <strong>abuse</strong>. The same women who fought to eliminatechild <strong>abuse</strong> and put an end to domestic violence arenow finding themselves the victims of various forms of<strong>abuse</strong>. This is unacceptable, and the women of <strong>OWL</strong>will not tolerate it.Since <strong>OWL</strong>’s inception we have been highlightingthe serious situations women face as they age. Elder<strong>abuse</strong> is believed to occur due to a multitude of factors,all of which disproportionately affect women. “Despitethe rapid aging of America, few pressing social <strong>issue</strong>shave been as systematically ignored as <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>,neglect, and exploitation, as illustrated by the followingpoints: Twenty-five years of congressional hearings onthe devastating effects of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, called the <strong>issue</strong> a‘disgrace’ and a ‘burgeoning national scandal.’ To date,there still is not a federal law enacted to address <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong> in a comprehensive manner.” 3 Despite continuedefforts the Elder Abuse Prevention Act of 2006 andthe Elder Justice Act of 2008 failed to pass. There alsois not a single federal employee working full-time on<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> in America. 4 The costs of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> to ourcountry include unnecessary human suffering, highhealth care costs and exhaustion of public resources. 5The leadership of <strong>OWL</strong> believes that one of the biggestbarriers to addressing the <strong>issue</strong> of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> is that" The same women who fought toeliminate child <strong>abuse</strong> and put an endto domestic violence are now findingthemselves the victims of various formsof <strong>abuse</strong>. This is unacceptable, andthe women of <strong>OWL</strong> will not tolerate it. "the American public is unaware of the severity of theproblem and its effect on women. Experts in the field of<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> prevention compare the current knowledgeof and response to <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> to the state of child <strong>abuse</strong>a generation ago. 6In the twenty years spanning from 1980-2000, therehas been a dramatic increase in physical <strong>abuse</strong> of olderadults. 7 As the number of <strong>elder</strong>ly or vulnerable adultsincreases in America, the movement to combat <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong> is slowly gaining momentum and attractingthe attention of federal and state governments. It isestimated that in the 50-year span from 2000 to 2050,the number of Americans who are over 85 years old willmore than quadruple, increasing from 4.2 million to20.8 million. 8Advocates have been attempting to address <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong> for the last thirty years, gathering informationand trying to direct the public’s attention to the severityand prevalence of this <strong>issue</strong> in our society. There is stilla major shortage of data relating to <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, neglectand fraud. <strong>OWL</strong> believes that it is time to view this<strong>issue</strong> as a women’s <strong>issue</strong>. While <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> affects manymen in the US, it affects women three times more.In April 1981 the House Select Committee on Agingestimated that 4% of adults over age 65 were victimsof <strong>abuse</strong>. This report also stated that the total numberof <strong>abuse</strong>d <strong>elder</strong>ly is nearly equal to the nation’s entirenursing home population. 9 Now it is estimated thatbetween one and two million people age 65 or olderhave been exploited, injured, or otherwise mistreated bysomeone whom they depend on for care. 10The Prevention, Identification, and Treatment ofElder Abuse Act of 1981 was introduced to address thisserious <strong>issue</strong>. The bill was designed to encourage statesto make legislative changes to reach a federal minimum6

" Women will not sit idly by and watch otherwomen suffer from the effects of <strong>abuse</strong>and neglect in the twilight of their lives. "standard of protection, but it was not passed into law. 11Four years later, another report on <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> wasreleased estimating that one out of every twenty-five<strong>elder</strong>s, or 1.1 million people, were subject to <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>each year. 12 This report and the earlier report from 1984recommend that an <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> act be designed similarto the 1974 Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act.The 1984 report compared the amount of money thatstates were spending on the protection of children withthe amount spent on <strong>elder</strong>ly protection, and found thatstates were spending $22.14 per child and $2.91 per<strong>elder</strong> resident. 13 Throughout the 1990s, similar reportswere written, and studies showed both increases in<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> and a greater need for ways to deal with theproblem. However, there was not any federal progressmade and the recommendations from the 1980s remainfairly accurate to today’s needs. According to a reportreleased by the Congressional Research Service earlierthis year, out of the total federal dollars spent on <strong>abuse</strong>and neglect, 2% is spent on <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, 7% on domestic<strong>abuse</strong> and 91% on child <strong>abuse</strong>. 14In 2007 the Elder Justice Act was introduced bySenator Orrin Hatch (R-UT), supporting effortstowards raising national awareness on <strong>elder</strong> justice<strong>issue</strong>s; improving the quality, quantity and accessibilityof information; increasing knowledge and supportingpromising projects; developing forensic capacity;Institutional NeglectRuth an 89 year old woman, was in fairly good health when she entered an Iowa nursing home for physicaltherapy in 2008. When she left to return home 25 days later, the woman’s leg was rotting and consumed bygangrene and she died three months later. State and federal officials called this neglect, and fined the nursinghome $112,650. The nursing home owner is fighting back. He runs a lobbying organization and is complainingabout the fine to Iowa legislators. Stating that the inspections department is “flogging” nursing homes andblocking seniors’ access to care by imposing huge fines.Only a year prior to her death, Ruth was in good spirits and good health. Twice widowed, she lived alone in awell maintained independent apartment where she liked to crochet. She had recently renewed her driver’s licenseand had just returned from a trip to California, where she traveled by herself to visit her daughter. She was alifelong pianist and played on a regular basis from memory. She fell and fractured a bone in her left ankle. Herdoctors didn’t think that a cast was needed and they put her leg in a brace with a medical stocking and sent herto a short-term rehab nursing facility.Ruth’s doctors gave the nursing facility instructions to monitor the circulation in her leg and to check herskin every shift for any signs of swelling or redness. Over the month, Ruth complained of excruciating pain. Thestaff gave her pain medication but never evaluated the cause of her pain or checked her leg. Finally, a physicaltherapy aide noticed that Ruth’s leg smelled like “rotting meat” and noticed blood seeping through her stocking.When Ruth was rushed to a local hospital, it appeared that the wound dressing from the original hospital visithad never been changed. Ruth was diagnosed with gangrene and Doctors told her that they had to amputate herleg. Her leg was amputated below the knee, her condition deteriorated and she died shortly thereafter.The nursing facility acknowledged that they never removed the stocking, nor was Ruth examined by aPhysician during her 25 day stay at the nursing facility. Additionally, this wasn’t the first time this particularfacility had been fined for serious problems.Provided to <strong>OWL</strong> by NCCNHR - The <strong>National</strong> Consumer Voice for Quality Long Term CareSource: Article by Clark Kauffman, Des Moines Register and Tribune Company, November 16, 20087

providing victim assistance and “safe-havens” for at-risk<strong>elder</strong>s; increasing prosecution; training social workersand others on signs, symptoms, and prevention; anddeveloping special programs to support underservedpopulations including rural, minority and Indianseniors. 15 This bill did not become law, but the efforts toenact the Elder Justice Act continue.Right now it is up to the states to create adequatelegislation that encompasses all of the necessarycomponents to combat <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> from every angle.As with child <strong>abuse</strong> and violence against women,what has proven to be somewhat successful is society’sresponse with a system of detection of <strong>abuse</strong> followed bymanagement of the problem. 16What is Elder Abuse?As defined by the <strong>National</strong> Center on Elder Abuse(NCEA), <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> is “knowingly, intentionally ornegligently causing harm or a serious risk of harm to avulnerable adult.” 17 Each state’s definition of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>is slightly different, but the main types of <strong>abuse</strong> includedin the definition are: Physical Abuse, Sexual Abuse,Emotional Abuse, Neglect, Exploitation, Abandonment,and Self-Neglect, as defined below.• Physical Abuse - Inflicting or threatening toinflict physical pain or injury on a vulnerableadult, or depriving them of a basic need.• Sexual Abuse - Non-consensual sexual contactof any kind.• Emotional Abuse - Inflicting mental pain,anguish or distress on an <strong>elder</strong> person throughverbal or non-verbal acts.• Exploitation - The illegal taking, misuse orconcealment of funds or property or assets of avulnerable adult.• Abandonment - The desertion of a vulnerableadult by anyone who has assumed theresponsibility for care or custody of that person.• Self-Neglect - Behavior of the <strong>elder</strong>ly person thatthreatens his/her own health or safety. 18Currently there are 21 states reporting self-neglectin a separate category as its own independent form of<strong>abuse</strong>. 19 There are also two categories of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>:Domestic Elder Abuse and Institutional Elder Abuse.Domestic Elder Abuse can refer to several differenttypes of <strong>abuse</strong>, but is generally perpetrated by someonethat has a special relationship with the <strong>elder</strong>ly person,and occurs in the home. Institutional Elder Abuserefers to <strong>abuse</strong> occurring in residential care facilitiessuch as nursing homes, foster homes, group homes, andassisted living communities. The persons perpetratingInstitutional Elder Abuse are those that generally havea legal or contractual obligation to care for the <strong>elder</strong>lyperson, such as the caregivers, staff or administrators ofthe institution. 20Domestic Elder AbuseIt is difficult to know how many of our <strong>elder</strong>lyare being <strong>abuse</strong>d in a domestic setting because ofthe nature of the problem. There is not a uniformdefinition addressing both <strong>abuse</strong> and neglect, and nocomprehensive, effective reporting system is solidly inplace. 21 In 1998 the Administration for Children andFamilies and the Administration on Aging collaboratedwith the <strong>National</strong> Center on Elder Abuse under acongressional mandate to produce the best study of <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong> in the U.S. This study was called the <strong>National</strong>Elder Abuse Incidence Study (NEAIS). 22 Findings inthe study revealed that in 1996, nearly half a millionpeople age 60 and over had experienced <strong>abuse</strong> or neglectin domestic settings. However, only 16% of these caseswere reported to Adult Protective Services agencies.This study also determined that <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> is harder todetect than child <strong>abuse</strong> because of the social isolationof the <strong>elder</strong>ly. 23 Oftentimes the <strong>elder</strong>ly are completelydependent on their <strong>abuse</strong>r for basic daily needs, andif they report the <strong>abuse</strong>, they feel that they would beunable to care for themselves or will have to be placed ina nursing home. 24 In this respect, the nature of domesticviolence against the <strong>elder</strong>ly is slightly different from thesituation of a battered woman. In domestic <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>,approximately 90% of <strong>abuse</strong>rs are related to the victim.Reporting to Adult Protective Services has been risingand between the years 1996-2004 the reported casesrose from 115,110 to 253,426. 25 Elderly victims havethe same reasons for not reporting <strong>abuse</strong> as other classesof victims. They may feel ashamed or embarrassed ofthe <strong>abuse</strong> and want to keep it a private matter. Withdomestic violence being talked about more openlyin younger generations, the door may open for <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong> to be discussed more freely as long as advocates8

are successful in educating the public of the problem.The <strong>elder</strong>ly, due to generational differences, may stillsubscribe to the belief that domestic <strong>abuse</strong> is a private<strong>issue</strong> and something that they have to deal with as afamily. 26Family CaregivingConventional wisdom suggests that there is aconnection between caregiver “burden” and <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>.It is true that most <strong>abuse</strong> and neglect occurs at the handof someone the <strong>elder</strong> knows. However, the researchis clear that there is no definitive cause and effectrelationship between “burden” and the care situationand <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> and neglect.Many studies have proven that some caregivershave large demands and do not experience high levelsof stress, and caregivers with fewer demands canexperience high levels of stress. 27 More importantly, thecaregivers’ attitude toward the caregiving and the healthstatus of the person they are caring for have provedto play a greater role in whether or not <strong>abuse</strong> occurs.Also important is the quality of the family caregiver’srelationship with the person needing care prior to thebeginning of the care. Caregivers who perpetrate <strong>abuse</strong>should be held accountable, but a failure of policymakers and law enforcement officials to acknowledgeand address the demands we place on a family caregiverand the nature of the relationship between the persongiving and the person receiving care is a failure to reallylook at the <strong>issue</strong> from all angles. 28Women’s organizations and caregiving organizationshave shied away from discussions about womencaregivers as <strong>abuse</strong>rs. The leadership of <strong>OWL</strong> feels verystrongly that we need to avail caregivers to the servicesand supports they need, have open conversations aboutdifficult care giving situations, and pay close attentionto all factors that are related to and have the potentialto reduce the risk of <strong>abuse</strong> and neglect. Policy makersmust understand that not all families can manage thecaregiving tasks and responsibilities that they are facedwith as the “default” long-term care provider. Norshould the norm of family care pose a barrier to honestdiscussion about the difficulty of giving care or create astigma around a woman who chooses not to or is unableto be a caregiver herself.Nursing Home RapeIn 2003 Eleanor*, a 90 year old nursing homeresident was raped while living in a nursing facilityin Elmore County, Alabama. Since Eleanor wassuffering from dementia investigators had to waituntil preliminary tests came back from forensicsbefore determining if a crime had occurred.The report came back proving that the evidencecollected was semen. The alleged perpetratorwas a 50 year old male Licensed Practical Nurse(LPN) named Marion Sheppard who worked atthe facility. Additionally, the facility knew thatMr. Sheppard had a history of sexual <strong>abuse</strong> yet thefacility’s administrative staff did not implementsafety measures when it learned that he wasstaying several hours past his assigned shift. In2005 Sheppard was indicted by a grand jury on acharge of abusing an <strong>elder</strong>ly nursing home patient.However, his case was dismissed in 2006 due tolack of evidence and the prosecution's inability tomeet the burden of proof linking the crime to theperpetrator.This was not the first time that the Sheppardhad been accused of <strong>abuse</strong>. On his employmentapplication, the suspect revealed that in 2000he was accused of sexually abusing an 86 yearold woman, but the case was dismissed for lackof evidence. As it turned out, the victim in theprevious grand jury indictment was sufferingfrom dementia, and when she was asked in courtwho attacked her, she pointed at the presidingthe judge. Under the rules of evidence, victimsof <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, do not have the same protectionsand rights as child <strong>abuse</strong> and domestic violencevictims therefore the judge had no choice but todismiss the case.Information Provided to <strong>OWL</strong> byNCCNHR – The <strong>National</strong> ConsumerVoice for Quality Long Term CareSources: Montgomery Adviser, Nurse indicted insex <strong>abuse</strong> case by Marty Roney, August 23, 2005www.nursingassistants.net - JusticeHappens December 9, 2006*name has been changed9

Institutional Elder AbuseAs a requirement under the <strong>Older</strong> AmericansAct, states have developed Long Term Care (LTC)Ombudsman Programs to try and sort through and dealwith incidents of <strong>abuse</strong>. 29 Ombudsmen are advocatesfor the residents of nursing facilities, care homes andassisted living communities and are generally trainedto resolve disputes. The Ombudsman Programs arealso situated to address complaints and advocate forimprovements within the long-term care system in theirstate. In 2007 there were close to 14,000 institutionalcomplaints of <strong>abuse</strong>, gross neglect and exploitation thatwere investigated by the Ombudsman offices. 30 Many ofthe problems include delays in reporting, under-trainedstaff, and lack of oversight by the Medicaid and Medicare“ Long-term care ombudsmen workon a daily basis to prevent <strong>abuse</strong>,neglect, and exploitation as well asto assist residents who are victimsdue to systems failures and violence.Each year, they help thousands ofresidents who have been victimizedget the help and support they need. ”- Lori Smetanka, Director, <strong>National</strong>LTC Ombudsman Resource Centerprograms. 31 Many of the state Ombudsmen Programsare staffed by volunteers, making it difficult to haveenough people investigating allegations. Many times,the volunteer ombudsman is the only person visiting oradvocating on behalf of a nursing home resident.The NCEA states that the main reasons forinstitutional <strong>abuse</strong> include stressful working conditions,staff shortages, staff burnout and inadequate stafftraining. 32 The turnover is so high, that facilitiesoftentimes have difficulty keeping up with backgroundchecks and are unable to verify caregiver qualifications.In a 2000 study, evaluations showed that when caregiverswere educated on the <strong>issue</strong>s of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, Alzheimer’sdisease, how to access resources, and the caregiver’s ownrisk of <strong>abuse</strong> by residents, that there was a change inattitude, behavior and knowledge by the participatingstaff. 33 Education and training programs for caregiversare seen as one of the best ways to prevent <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>.It is also imperative that public education campaignsinvolving media, literature and various advocacyresources are directed at seniors themselves. 34Prosecution of an AbuserProsecution in <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> cases is exceedinglydifficult. The victim often fears perpetrator retaliation,especially if the <strong>abuse</strong>r is a family member. Oftentimesthe victim is incapacitated or suffering from dementiaor Alzheimer’s disease and is unable to be a witness inthe case. The “Rules of Evidence” state that hearsay isinadmissible. Hearsay is an out of court statement thatone party wants to use in the court proceeding. In manystates, there are hearsay exceptions used in child <strong>abuse</strong>cases and cases concerning mentally ill adults. This typeof exception should be extended to the victims of <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong> to assist the prosecution in meeting their burdenof proof. In special circumstances the exception shouldallow for testimony to be videotaped or for the victim toappear via closed circuit television as is done in certainchild <strong>abuse</strong> cases. 35Addressing the ProblemTo adequately address the problem of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>,there are many steps that must be taken. There mustfirst be increased public awareness, improvements inand development of comprehensive state and federallegislation, cooperation between law enforcementand health care providers, education and trainingon preventing and detecting <strong>abuse</strong>, enforcement ofmandatory reporting regulations, support for caregivers,and improvement in hiring practices. 36 On the federallevel, Congress began to address the problem by creatingand funding a new chapter to the <strong>Older</strong> Americans Actcalled Section VII, Vulnerable Elder Rights. Section VIIhas been used primarily for education and to promotethe collaboration of different agencies and also defines<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, allowing for federal money to be providedto the NCEA for training and awareness. However, thissection has been flat-funded or underfunded for thepast several years and is largely lacking the adequatetools necessary to address the real needs of older adults.Relative to the Violence Against Women Act and10

Child Abuse Prevention Act, there is very little fundingavailable for Adult Protective Services, or for sheltersfor the <strong>elder</strong>ly. 37 When Congress passed bills protectingchildren and violence against women, they created afederal infrastructure that included funding. What isknown from these other successful pieces of legislationis that the best way to prevent this <strong>abuse</strong> is through acollaboration of law enforcement and social services. 38The current levels of collaboration are inadequate, andstronger mandates from the federal government canmore effectively combat the problem.<strong>OWL</strong> advocates for comprehensive <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>prevention laws using the models of prevention forviolence against women and child <strong>abuse</strong>. There arealready established methods for addressing thesecomplicated <strong>issue</strong>s, such as offender treatment programsand coordinated community response programs, bothof which have proven to educate and slowly change thesocial views within communities. 39 Studies have alsoshown that interventions into child <strong>abuse</strong> situationsor violent relationships have been successful. Sincemost forms of child or relationship <strong>abuse</strong> are in thecontext of a dependency relationship, there are clearparallels that can be drawn to <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> in whichthe <strong>elder</strong> is completely dependent on the caregiver. 40When a caregiver does not understand why the <strong>elder</strong>is behaving in a certain way, it may be useful to initiatea form of specific behavioral training. “Cognitivebehavioralmethods addressing misunderstandingsabout the reasons for a child’s behavior, misattributions,and limited knowledge of normal development, forexample, have been particularly successful with abusiveparents and would likely apply to <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> caregiversas well.” 41 Empowerment methods, such as volunteeradvocacy programs or support groups for the <strong>elder</strong>ly, arealso a way to address the problem.In traditional domestic violence situations, shelters or“safe homes” have been set up as safe places for victimsto live for a short period of time. For a child who is being<strong>abuse</strong>d, the foster care system has been implementedand improved over the years. Due to the health andinfirmity of some older adults, a similar system shouldbe set up in every state that allows for safe and medicallyadequate places that can take the victims of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>.This should be funded by both the state and federalgovernments.Collaborative ProgramsThe Department of Justice has also developed aNursing Home Initiative that is looking into nursinghome <strong>abuse</strong>. As a result, there are state groups thatidentify nursing homes where regulations are notbeing met and pursue action against them. 42 Floridahas implemented a team approach for investigatingnursing and assisted living facilities called “OperationSpot Check.” This program is designed to use theresources of the state Attorney General’s office, Agencyfor Health Care Administration, Long-Term CareOmbudsman Program, fire and police departments,and the Department of Children and Families to makerandom checks on nursing facilities. 43 The unique aspectof this program is that it does not require additionalfunding because it pools the resources of agencies thatare already required to do this type of activity. 44Oregon has developed a program designed to protectthe <strong>elder</strong>ly against financial exploitation. The programstarted in 1994 and developed a task force that usestrained bank employees to identify possible <strong>abuse</strong>. 45 Itis partially funded by the Office of Victims of Crimeat the Department of Justice and works closely withthe Oregon Bankers Association and AARP. There arecases in which both federal and state agencies worktogether to combat institutional <strong>abuse</strong>. Ideally, thissort of collaboration would take place in every state,but currently there are very few examples. Louisianahas another example of effective collaboration: A StateWorking Group made up of individuals from the USAttorney’s offices, the Federal Bureau of Investigation,the Office of the Inspector General, Medicare/MedicaidServices, the state Attorney General’s Office, the stateDepartment of Health and Hospitals, and the stateLong-Term Care Ombudsman Program. 46 If morestates develop these types of collaborative efforts, it willeffectively spread awareness and more efficiently use theresources already available to combat <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>.Legislation – Why don’t we havecomprehensive federal legislation yet?A study done by the University of Iowa looked atthe problem of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> in the context of publicchoice. This study looked at the types of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> law11

and also the motivations behind the laws, taking intoconsideration interpretive regulations and legislation. 47The study focused primarily on domestic <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>. Itdetermined that there are three sets of public decisionmakers that influence <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> legislation the mostheavily. These include legislators, state welfare officials,and APS investigators. Legislators are generallyinfluenced by three factors: first, they have to confronttheir voting public; second, they act according to whatthey like and want; and third, they act according tocertain special interest groups that they need supportfrom in order to fund campaigns. 48 State officials areusually concerned with maintaining a reputation afterthey leave their public jobs, and also with maximizingbudgets, which can influence the legislation greatly.Based on this reasoning, a possible conclusion as towhy we have not adequately addressed <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> withlegislation is that we still do not have enough people withwhom this <strong>issue</strong> resonates. Because the <strong>issue</strong> affects morewomen than men, it is possible that with an increaseof women in leadership, more attention will be devotedto a solution. However, with women representing only16.8% in the U.S. House of Representatives and 17% inthe U.S. Senate, we have a lot of work to do. 49The study concluded that there was, “no real pressuregroup for the aged and dependent population that doesnot reside in nursing homes.” 50 This shows that thereis not a significant enough advocacy movement forthose <strong>elder</strong>ly individuals living outside of a facility. Inorder for effective legislation to be passed to protectthe <strong>elder</strong>ly, people must be educated about the kinds of<strong>abuse</strong> occurring in homes and in institutional settings.Once there is awareness of the true nature of theproblem, advocates will be able to educate legislators toimplement adequate laws that protect victims. <strong>OWL</strong>is the advocacy organization that will bring this <strong>issue</strong>to light. Women will not sit idly by and watch otherwomen suffer from the effects of <strong>abuse</strong> and neglect inthe twilight of their lives.ENDNOTES1 American Bar Association Position onthe Elder Justice Act 20072 2004 Survey of State Adult Protective Services:Abuse of Adults 60+ <strong>National</strong> Committee forthe Prevention of Elder Abuse and NAPSA.3 108 Cong. Rec S12047 (December 8, 2004).4 Id.5 Id.6 John B. Breaux & Orrin G. Hatch, Confronting ElderAbuse, Neglect, and Exploitation: The Need for ElderJustice Legislation, 11 Elder L.J. 207, 223 (2003).7 Margaret F Brinig, The Public Choice of Elder AbuseLaw, 33 Legal Stud. 517,518 (June 2004).8 Sarah S. Sandusky, The Lawyer’s Role in Combatingthe Hidden Crime of Elder Abuse, 11 Elder L.J. 459,466 (2003) from the <strong>National</strong> Center on ElderAbuse: <strong>National</strong> Elder Abuse Incidence Study.9 John B. Breaux & Orrin G. Hatch, Confronting ElderAbuse, Neglect, and Exploitation: The Need for Elder JusticeLegislation, 11 Elder L.J. 207, 213 (2003). Referencing SelectHouse Comm. on Aging, 97th Cong., Elder Abuse (AnExamination of a Hidden Problem) (Comm. Print 1981).10 Fact Sheet, <strong>National</strong> Center on Elder Abuse usingstatements from - Elder Treatment: Abuse Neglect andExploitation in an Aging America 2003. Washington,DC: <strong>National</strong> Research Council Panel to ReviewRisk and Prevalence of Elder Abuse and Neglect.11 Breaux & Hatch, Supra Note 5 at 214.12 Id.13 Id.14 Kirstent J. Colello, Congressional Research Service,Memorandum, Summary of Federal Programs andInitiatives Related to Prevention, Detection, andTreatment of Elder Abuse (July 8, 2008).15 Senator Orrin Hatch, Elder Justice Act 2007.16 Richard J. Bonnie, Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect,and Exploitation in an Aging America p. 502.17 <strong>National</strong> Center on Elder Abuse www.<strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong>center.org.18 Id.19 Brinig, supra Note 6 at 529.20 Id.21 Breaux & Hatch, supra note 5 at 214.22 Id.23 Id. at 21.24 Sandusky, supra Note 7 at 459.25 Breaux & Hatch, supra note 5 at 220.26 Sandusky, supra note 7 at 459.27 Nerenberg, Lisa. Elder Abuse Prevention 65(Sheri W. Sussman ed., Springer PublishingCompany LLC 2008) (2008).28 Id. at 69.29 http://nursinghomeaction.org/static_pages/ombudsmen.cfm.30 <strong>National</strong> LTC Ombusdman Resource Center,Complaints for Fiscal Year 2007.31 Supra Note 28.32 http://www.<strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong>center.org/default.cfm?p=nursinghome<strong>abuse</strong>.cfm.33 Bonnie, supra note 15, at 511-512.34 Id. at 518.35 Patrick Flood & William H. Sorrell, Project Elder ReachCommittee Report, State of Vermont, Dec. 10, 200136 http://www.<strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong>center.org/default.cfm?p=nursinghome<strong>abuse</strong>.cfm.37 <strong>National</strong> Committee for the Prevention of ElderAbuse, http://www.prevent<strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong>.org38 Breaux & Hatch, supra note 5 at 230-231.12

39 Bonnie, supra Note 15 p. 516.40 Id.41 Id.42 Breaux & Hatch, supra note 5 at 226.43 Id. at 228-229.44 Id. at 229.45 Id.46 Id. at 250-251.47 Brinig, supra note 6 at 521-522.48 Id. at 523.49 Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP),Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University,Women in Elective Office 2009 Fact Sheet.50 Brinig, supra note 6 at 544.Age and Intimate ViolenceProfessor Cheryl Hanna, J.D.Vermont Law SchoolDuring the past two decades, much theoreticaland practical work on domestic violence has emerged.Many such works examine domestic violencethrough the gender lens. Domestic violence wasinitially understood within the larger context ofgender discrimination, given that the vast majorityof domestic violence victims are women. Morenuanced analyses followed, looking at the impact ofrace, ethnicity, class, disability, sexual orientation,and citizen status on domestic violence and our legalresponses to it. Such analyses have greatly aided ourunderstanding of domestic violence and have helpedshape the development of legal policies that respondto victims’ needs.The relationship between age and domesticviolence, however, has largely gone unexplored.Throughout one’s life, as long as one is in an intimaterelationship, one is always at some risk of domesticviolence. Whether someone is fourteen or eightyyears old, the primary reason one engages in verbal,physical, or sexual <strong>abuse</strong> against an intimate partneris a desire for control. Violence is often triggeredby sexual conflict, sexual jealousy, or a fear that therelationship is changing or will end.The context for domestic violence is intimacy--both sexual and emotional. Yet, one of the reasons weoften “miss” the young and the <strong>elder</strong>ly in our analysisof domestic violence is that our culture denies that theyoung and the <strong>elder</strong>ly engage in the kinds of romanticor sexual relationships that can lead to violence. Weoften misconstrue violence by young people as beingsomething other than domestic violence. We mayattribute violence in dating relationships to individualsocial problems, or we may minimize it as innocenthorseplay. It is telling that among the volumes of legalacademic literature on domestic violence, for example,few articles focus specifically on adolescent datingrelationships.Similarly, there is a popular misunderstanding thatviolence among the <strong>elder</strong>ly is triggered by “caregiver”stress. When <strong>abuse</strong> happens in the context of anintimate relationship, however, it is almost alwaysan outgrowth of domestic violence. Once an <strong>elder</strong>lycouple reaches a certain age, we label it “<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>”when, in fact, it is the similar pattern of domestic<strong>abuse</strong> that we see among younger couples. The overallpattern of behavior in violent relationships is similarregardless of the age of the <strong>abuse</strong>r or the victim. Onemight speculate that older women experience moreviolence than younger women, because older womenare likely to take less advantage of the available legal andsocial interventions and to maintain more traditionalviews of domestic violence as a private family matter.Their spouses, too, would arguably be more likely tohave come of age in a time when it was consideredacceptable, or at least not punishable, to batter one’sspouse. Yet, violent crime data shows that the youngare more likely to engage in violence, includingdomestic violence. Data from the Federal Bureau ofInvestigation Uniform Crime Reports shows that,between 1996 and 2001, there were 5,148 incidentsof domestic <strong>abuse</strong> perpetrated by a significant otheragainst someone over age sixty-five. In contrast, therewere 47,000 domestic violence incidents perpetratedby a significant other against someone under the age ofeighteen. This suggests that the older one gets withoutexperiencing violence, the less likely he or she willbecome a victim of it.The earlier in her life a woman is exposed to violenceor becomes violent, the more throughout her life, andthe more likely she is to experience a host of othersocial problems, including an increased likelihood ofending up in the criminal justice system. Yet, mostof our legal and social strategies have focused almostexclusively on adults. By the time these adults end upin the criminal justice system, they may already havelong histories of violence within their relationships.Thus, early intervention could be an effective strategyfor reducing intimate violence both by and againstwomen. In turn, such intervention could reducewomen’s exposure to the criminal justice system.Reprinted from Sex Before Violence: Girls, Dating Violence, and(Perceived) Sexual Autonomy, 33 Fordham Urb. L. J. 437 (2006).13

Elder Abuse: A Women’s IssueLisa Nerenberg, MSW, MPHSince <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> first emerged into the public’sconsciousness in the late 1970s, it has been describedas a caregiving <strong>issue</strong>, domestic violence, a hate crime,a victims’ rights <strong>issue</strong>, a syndrome, and a public healthconcern. Somewhat surprisingly, in light of the fact thatit disproportionately affects women, there has been littleattention to the unique circumstances, vulnerabilities,and needs of <strong>abuse</strong>d <strong>elder</strong>ly women. <strong>OWL</strong>’s focus on<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> for its 2009 Mothers Day Report providesa long overdue occasion to consider these factors and toexplore the emerging global perspective on <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>as a women’s <strong>issue</strong>.Women as Victims of Elder AbuseStudies that examine cases of <strong>abuse</strong> and neglect thatare reported to agencies, health care providers, and lawenforcement consistently show that the majority ofvictims are women (<strong>National</strong> Research Council, 2003).This appears to be true for all forms of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>except abandonment, and the ratio of female to malevictims varies significantly depending on the type of<strong>abuse</strong> (<strong>National</strong> Center on Elder Abuse, 1998).In recent years, the field of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> prevention hasattempted to achieve a clearer understanding of victims’experiences and needs, particularly when victims declinehelp. Perhaps nowhere is this emphasis more apparentthan in the field’s response to domestic violence.Researchers, practitioners, and advocates have cometo recognize that domestic violence continues into oldage and may get worse as a result of age-related factorslike retirement and the role reversals that result fromlife-style changes or physical decline. Violence may alsobegin in old age, although “late onset” violence oftenstems from dementias and is generally not considered tobe domestic violence if the power and control motive,a defining feature of domestic violence, is not present.Elders may also enter into violent relationships inadvanced age.The field of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> prevention has drawnheavily upon the wisdom and experiences of thedomestic violence movement in adapting services and" Somewhat surprisingly, in light of thefact that it disproportionately affectswomen, there has been little attention tothe unique circumstances, vulnerabilities,and needs of <strong>abuse</strong>d <strong>elder</strong>ly women. "interventions for older women. Advocates for youngervictims have long understood that domestic violenceis rooted in society’s acceptance of men’s right todominate their intimate partners through violence andthreats. They further recognize that these attitudes aresupported and reinforced by institutions, including thejustice system. Historically, acts of violence that wereconsidered to be crimes when the victims were strangerswere treated as “family matters” when victims wereintimate partners. Women were justifiably distrustfulof the system; the vast majority of domestic violencevictims still do not report their injuries, and most ofthose who do later minimize the <strong>abuse</strong> or recant theirstories. Interventions to overcome these barriers focuson empowering women through consciousness raisingand creating support groups, as well as ensuring theirsafety through restraining orders, shelters, and safetyplanning.Domestic violence advocates have also long recognizedthe social and economic hurdles that victims face. Formany women, leaving abusive partners results in poverty,and strong social pressures to tolerate <strong>abuse</strong> discourageothers from leaving or accepting help. The domesticviolence movement has increasingly acknowledged thatgender-based inequalities and discrimination are not theonly barriers that women face: race, class, age, religion,and sexual orientation also play a role. Recognizingthat these “macro” problems call for macro solutions,advocates have focused on changing attitudes aboutviolence against women, enacting laws to criminalizedomestic violence, and promoting economic selfsufficiencyfor women.Although there have been few studies exploring theimpact of domestic violence on <strong>elder</strong>ly women, practiceexperience and anecdotal evidence suggest that olderwomen encounter many of the same barriers as youngerwomen and additional ones. Violence against older14

women may result in greater injury, and older women’sability to escape violence may be impeded by physicaldisability, communication barriers, and the fact thatmost traditional domestic violence services, includingshelters, cannot accommodate those with special needs.The social and cultural attitudes and stigmas that<strong>elder</strong>ly women face are likely to be more pronouncedthan those experienced by younger women reflectingchanging attitudes about women, violence, and divorce.Elderly women also face economic barriers. Accordingto the U.S. Census, nearly one in five single, divorced orwidowed women over the age of 65 is poor, and the riskof poverty for older women increases with age. Womenages 75 and up are over three times as likely to be living" the U.N. Secretary Generalacknowledged the role of both sexismand ageism as contributing factorsin <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, and cast <strong>abuse</strong> withinthe broader landscape of 'poverty,structural inequalities and human rightsviolations' that disproportionatelyaffect women worldwide "in poverty as men in the same age range. Their healthcare may be tied to their husbands’ employment, creatingadditional disincentives to leave abusive relationships.Across the country, communities have respondedto domestic violence against older women by adaptingdomestic violence services and interventions for olderwomen. Many communities now have shelters thatcan serve <strong>elder</strong>s with disabilities and support groups.Restraining orders and safety planning are increasinglybeing used to ensure victims’ safety.But while advocates in the United States haveembraced domestic violence theory and practice as itrelates to individual women, mainstream programshave not focused on the structural inequalities thatheighten risk, including poverty and discrimination. Insharp contrast, those who have addressed <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> incommunities of color in the US have recognized howpoverty fosters isolation and dependency, heightensthe demands on caregivers, and reduces access topreventative services, legal recourse, and treatment.Policy makers, researchers, and advocates in othercountries, particularly developing countries, haverecognized <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> as a human rights <strong>issue</strong> thatsignificantly affects women (Nerenberg, 2002). Ina report prepared for the Second World Assembly onAging, the U.N. Secretary General acknowledged therole of both sexism and ageism as contributing factors in<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, and cast <strong>abuse</strong> within the broader landscapeof “poverty, structural inequalities and human rightsviolations” that disproportionately affect womenworldwide. In particular, the report cites patrilinealinheritance laws and land rights as factors contributingto the vulnerability of older women (United Nations,2002). That same year, the UN sponsored an electronicdiscussion forum, “Gender Aspects of Violence andAbuse of <strong>Older</strong> Persons” to further explore the role ofgender in <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> (AgeingNet, 2002).As part of an initiative to develop a global strategy on<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, the World Health Organization (WHO);in collaboration with the International Network forthe Prevention of Elder Abuse (INPEA), HelpAgeInternational (a global network of NGOs), andacademic institutions from around the world; conductedfocus groups comprising health care workers in bothdeveloping and developed countries. The groups focusedon gender, socio-economic status, social exclusion,poverty, traditional cultural roles, and human rights,highlighting a prevailing view that women, particularlythe poor, childless, and widowed, are most affected(Krug et al, 2002; WHO/INPEA, 2002).The report further acknowledges that shortages ofcaregivers and long-term care also contribute to <strong>abuse</strong>and neglect. Decreasing rates of communicable diseasesin the developing world over the last few decades hasincreased the prevalence of disabling diseases at a timewhen women worldwide are entering the job market,thereby reducing their availability as family caregivers.Elder Abuse as a Caregiving IssueElder <strong>abuse</strong> often occurs within the context ofcaregiving, a realm that is also dominated by women.According to the Family Caregiver Alliance, 59-75%of caregivers are women, and women caregivers devote15

as much as 50% more time than male caregivers toproviding care.Caregiving has many rewards and challenges. It canbe a time of heightened intimacy and closeness betweenfamily members. However, it can also create tensionsand conflicts that set the stage for <strong>abuse</strong>. In recent years,researchers have identified specific factors associatedwith risk (Nerenberg, 2002; Wolf, 1998). These includethe quality of relationships between caregivers and carereceivers prior to the onset of the disability. Caregiverswho had close and positive relationships with patients inthe past were found to be less likely to <strong>abuse</strong> than thosewho did not; and care receivers who were violent towardtheir caregivers prior to the onset of their illnesses werefound to be more likely to experience <strong>abuse</strong>. Otherfactors that predict <strong>abuse</strong> by caregivers include disturbingbehaviors by care receivers such as combativeness orverbal aggression; caregivers’ negative perceptions aboutcaregiving; and caregivers’ low self esteem. Caregivingcan also create financial hardships. Female caregivers intheir 50’s or 60’s who care for parents are 2.5 times morelikely than their non- caregiving counterparts to live inpoverty (Donato & Wakabayashi, 2005).Because women live longer than men, they are alsolikely to be on the receiving end of caregiving. Womencan expect to live an additional 28 years following their55th birthdays, to age 83, which is almost 4 years longerthan men. With increasing age come impairments anddisabilities that require care. Seventy percent of <strong>elder</strong>saged 75 and older who need assistance with dailyactivities are women (AARP Public Policy Institute,2002). The need for help heightens the risk of neglect andrenders <strong>elder</strong>s vulnerable to coercion, undue influence,and manipulation. It has also been observed that <strong>elder</strong>lywomen who outlive their spouses are often targeted forfinancial <strong>abuse</strong> by predators. Similarly, rates of cognitivedecline also increase dramatically with age. Over 50% ofpeople over the age of 80 suffer from dementias, whichraises the risk for such common forms of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> asinducing cognitively impaired <strong>elder</strong>s to sign documentsthey do not understand.In light of these risks and vulnerabilities, it is perhapsnot surprising that the rate of <strong>abuse</strong> in caregivingrelationships is extremely high. One recently releasedstudy in the United Kingdom suggests that half ofdementia caregivers <strong>abuse</strong> those they care for, with most<strong>abuse</strong> being verbal (Cooper et al 2009). Earlier studiesof physical <strong>abuse</strong> by caregivers have suggested rates frombetween 5 and 12% (Nerenberg, 2002).It would seem that these connections betweencaregiving and <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> would suggest fruitful areasof collaboration between the <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> and caregivingnetworks. Common interests might include for examplethe development of screening tools to identify high risksituations such as past conflict and domestic violence,services to support caregivers, and interventions aimedat easing interpersonal conflicts between care givers andcare receivers.Regrettably collaboration between the networks hasbeen minimal and in fact, both networks have tended todownplay the relationship between caregiving and <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong>, a reticence that stems from mutual distrust. Some,particularly advocates for <strong>elder</strong>ly victims of domesticviolence, fear that attributing <strong>abuse</strong> to the pressuresof caregiving will lead to bogus defenses by batterers,who will claim that “stress made me do it” (which somein fact do). On the other hand, caregivers and theiradvocates fear that if they admit to or report <strong>abuse</strong>;well-meaning caregivers will be treated as criminals.They also fear that people with dementias who commitviolence will become entangled with the criminal justicesystem. Their fears too are understandable in light of thefield’s current emphasis on criminalizing <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>.These fears of excusing the culpable and punishing theinnocent have lead to an impasse that has prevented bothnetworks from reaching out to the legions of caregiverswho are the backbone of our long term care system andprevented the two networks from working togetherto ensure appropriate responses. Clearly education isneeded to help professionals, law enforcement, judges,and the public understand the dynamics of bothdomestic violence later in life and caregiving, and todistinguish the actions of caregivers who need help fromunacceptable and criminal conduct.Other Areas of NeedDespite the significant progress that has been madein the last 15 years, much more remains to be done toensure the safety and security of <strong>elder</strong>ly women. Moreresearch, debate and analysis are needed to achieve a16

clearer understanding of <strong>elder</strong>ly women’s vulnerabilityto <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, its impact, and the economic, social, andpolitical forces that contribute to <strong>abuse</strong> and entrap olderwomen. It is imperative that advocates for the <strong>elder</strong>lywork with their colleagues in the fields of domesticviolence and caregiving, as well as other fields, to explorethe cumulative effects of ageism and sexism and otherthreats to older womenAs the field matures, we need to resist the lure of onesize-fits-allexplanations or solutions. Rather, we mustbroaden our perspective to encompass the full range ofwomen’s experiences as caregivers, care receivers, victimsand perpetrators. Perhaps this Mothers Day report willprovide the necessary impetus.REFERENCESAARP Public Policy Institute. (2002). Womenand long-term care (Fact Sheet). Washington,DC: Gregory, S. R., & Pandya, S. M.AgeingNet. (2002). Summary of INSTRAW electronicdiscussion forum on gender aspects of violence and<strong>abuse</strong> of older persons. Retrieved April 22, 2009from the WWW: http://www.un-instraw.org/en/docman/ageing/age-net-summary/view.htmlCooper, C., Selwood, A., Blanchard, M., Walker, Z.,Blizard, R., & Livingston, G. (2009). Abuse of peoplewith dementia by family carers: Representative crosssectional survey. British Medical Journal 338.Donato, K., & Wakabayashi, C. (2005). Women Caregiversare More Likely to Face Poverty. Sallyport, Magazineof Rice University Vol., 61 No.3. Spring 2005.Family Caregiver Alliance. (2001). Selected CaregiverStatistics (Fact Sheet). San Francisco, CA: Author.Krug, E. Dahlberg, I. Mercy, J. Zwi A. & Rafael,L (eds.), World Report on Violence and Health(World Health Organization, Geneva), 2002Nerenberg, L. (2002). Caregiver stress and <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>:Preventing <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong> by family caregivers. RetrievedApril 20, 2009, from http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/NCEAroot/Main_Site/pdf/family/caregiver.pdfNerenberg, L. (2002). A feminist perspective on gender and<strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>: A review of the literature Retrieved April 20,2009, from http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/NCEAroot/Main_Site/pdf/publication/finalgender<strong>issue</strong>sin<strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong>030924.pdf<strong>National</strong> Center on Elder Abuse. (1998). The <strong>National</strong> ElderAbuse Incidence Study, Final Report. WashingtonD.C.: The <strong>National</strong> Center on Elder Abuse.<strong>National</strong> Research Council. (2003). Elder mistreatment:Abuse, neglect, and exploitation in an aging America.Washington, DC: <strong>National</strong> Academies Press.United Nations. (2002). Abuse of older persons: Recognizingand responding to <strong>abuse</strong> of older persons in a globalcontext. Report of the Secretary-General.United States Census Bureau. (2008)Wolf, R.S. (1998). Caregiver stress, Alzheimer’s disease and <strong>elder</strong><strong>abuse</strong>,” American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 13(2), 81 83.WHO/INPEA.(2002). Missing voices: Views ofolder persons on <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>. Retrieved April 20,2009, from http://www.who.int/ageing/projects/<strong>elder</strong>_<strong>abuse</strong>/missing_voices/en/index.html.17

Protecting Your Motherfrom Financial Fraud and AbuseCindy Hounsell, J.D.,WISER, <strong>Women's</strong> Institute for a Secure Retirement“…no matter your age, finances or social status,none of us are beyond potential <strong>abuse</strong> or neglect, andany one of us, at any time, could become incapacitatedand in need of assistance.” Senator Gordon Smith, U.S.Senate Special Committee on Aging Hearing onExploitation of Seniors, September 7, 2006.Several months ago, Marion, age 90, received acall that ended up costing her thousands of dollars.The young man on the phone informed her that shehad won a million dollars in a special sweepstakes;all she needed to do was give him a $15,000“distribution fee” and the money would be hers. Hetold her she could do that by giving him her checkingaccount information. Over time and after severalmanipulative calls, this scammer received, in cashand in credit, over $20,000 of Marion’s moneybefore her family realized something was going on.Marion’s daughter, Ann, finally caught on to thescam when she noticed that her mother did not havemoney for food, despite the fact that her mother’smonthly income had always exceeded her expenses.The loss would have been much higher had Ann nottracked down the companies on the Internet that hadcashed the checks in several states. She was able torecover about $4,500 and stop additional leakage.Unfortunately, there was no help from the localpolice or the bank. The bank would not even reportit as a crime because Marion had freely given out theinformation; business as usual was their attitude.What is <strong>elder</strong> financial <strong>abuse</strong>? 1Elder financial <strong>abuse</strong> is the misuse of an older person’sproperty or financial resources without their consent orunderstanding. It is a crime that affects hundreds ofthousands of <strong>elder</strong>ly persons each year.Elder financial <strong>abuse</strong> is one of the fastest growingforms of <strong>elder</strong> <strong>abuse</strong>, and it costs older Americansmore than $2.6 billion per year. 2 As the holders ofthe largest percentage of wealth, and with access toequity reserves in family homes, the <strong>elder</strong>ly are primetargets for a growing number of unethical professionals.Financial exploiters, using fear tactics, take advantage of<strong>elder</strong>s by selling them financial products that are ofteninappropriate for their needs, or they engage them inother predatory lending practices.The consequences of this type of <strong>abuse</strong> are particularlydire for older women. Being swindled out of your lifesavings is devastating and, indeed, life-threatening ifyou are an 80-year-old woman already stretching tomake ends meet with only Social Security benefits and asmall savings account. Not only have you lost what youhave saved, but you will probably face two additionalproblems common to <strong>abuse</strong> victims—stress and serioushealth care concerns.Because older women are identified as easy marks,they are targeted by the unscrupulous. According tothe <strong>National</strong> Adult Protective Services Association(NAPSA) the “typical” victim of <strong>elder</strong> financial <strong>abuse</strong> isbetween the ages of 70 and 89, white, female, frail andcognitively impaired. She is trusting of others and maybe lonely or isolated.Types of Financial Exploitation:Financial <strong>abuse</strong> can cover a broad range of activities,from misusing credit and debit cards to stealingfrom joint bank accounts or writing checks withoutauthorization. Financial <strong>abuse</strong> can escalate from theftof pension or benefit checks to identity theft. It caninvolve pressure or threats that make the <strong>abuse</strong>d persontransfer or give away money or possessions. It can alsobe deceitful financial salespeople whose only goal is tosell inappropriate products such as trusts, long-termcare insurance, reverse mortgages, and annuities thatindividual buyers do not understand or may not need. 318