Weathering morphologies of the Fontainebleau Sandstone and ...

Weathering morphologies of the Fontainebleau Sandstone and ...

Weathering morphologies of the Fontainebleau Sandstone and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

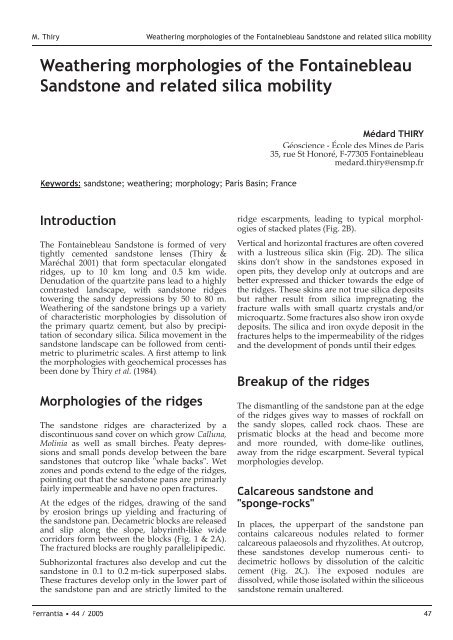

M. Thiry <strong>Wea<strong>the</strong>ring</strong> <strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> <strong>and</strong> related silica mobility<strong>Wea<strong>the</strong>ring</strong> <strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong><strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> <strong>and</strong> related silica mobilityKeywords: s<strong>and</strong>stone; wea<strong>the</strong>ring; morphology; Paris Basin; FranceMédard THIRYGéoscience - École des Mines de Paris35, rue St Honoré, F-77305 <strong>Fontainebleau</strong>medard.thiry@ensmp.frIntroductionThe <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> is formed <strong>of</strong> verytightly cemented s<strong>and</strong>stone lenses (Thiry &Maréchal 2001) that form spectacular elongatedridges, up to 10 km long <strong>and</strong> 0.5 km wide.Denudation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> quartzite pans lead to a highlycontrasted l<strong>and</strong>scape, with s<strong>and</strong>stone ridgestowering <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>y depressions by 50 to 80 m.<strong>Wea<strong>the</strong>ring</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone brings up a variety<strong>of</strong> characteristic <strong>morphologies</strong> by dissolution <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> primary quartz cement, but also by precipitation<strong>of</strong> secondary silica. Silica movement in <strong>the</strong>s<strong>and</strong>stone l<strong>and</strong>scape can be followed from centimetricto plurimetric scales. A first aemp to link<strong>the</strong> <strong>morphologies</strong> with geochemical processes hasbeen done by Thiry et al. (1984).Morphologies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridgesThe s<strong>and</strong>stone ridges are characterized by adiscontinuous s<strong>and</strong> cover on which grow Calluna,Molinia as well as small birches. Peaty depressions<strong>and</strong> small ponds develop between <strong>the</strong> bares<strong>and</strong>stones that outcrop like "whale backs". Wetzones <strong>and</strong> ponds extend to <strong>the</strong> edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridges,pointing out that <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone pans are primarlyfairly impermeable <strong>and</strong> have no open fractures.At <strong>the</strong> edges <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridges, drawing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>by erosion brings up yielding <strong>and</strong> fracturing <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone pan. Decametric blocks are released<strong>and</strong> slip along <strong>the</strong> slope, labyrinth-like widecorridors form between <strong>the</strong> blocks (Fig. 1 & 2A).The fractured blocks are roughly parallelipipedic.Subhorizontal fractures also develop <strong>and</strong> cut <strong>the</strong>s<strong>and</strong>stone in 0.1 to 0.2 m-tick superposed slabs.These fractures develop only in <strong>the</strong> lower part <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone pan <strong>and</strong> are strictly limited to <strong>the</strong>ridge escarpments, leading to typical <strong>morphologies</strong><strong>of</strong> stacked plates (Fig. 2B).Vertical <strong>and</strong> horizontal fractures are oen coveredwith a lustreous silica skin (Fig. 2D). The silicaskins don’t show in <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stones exposed inopen pits, <strong>the</strong>y develop only at outcrops <strong>and</strong> arebeer expressed <strong>and</strong> thicker towards <strong>the</strong> edge <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> ridges. These skins are not true silica depositsbut ra<strong>the</strong>r result from silica impregnating <strong>the</strong>fracture walls with small quartz crystals <strong>and</strong>/ormicroquartz. Some fractures also show iron oxydedeposits. The silica <strong>and</strong> iron oxyde deposit in <strong>the</strong>fractures helps to <strong>the</strong> impermeability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridges<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> ponds until <strong>the</strong>ir edges.Breakup <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridgesThe dismantling <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone pan at <strong>the</strong> edge<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridges gives way to masses <strong>of</strong> rockfall on<strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>y slopes, called rock chaos. These areprismatic blocks at <strong>the</strong> head <strong>and</strong> become more<strong>and</strong> more rounded, with dome-like outlines,away from <strong>the</strong> ridge escarpment. Several typical<strong>morphologies</strong> develop.Calcareous s<strong>and</strong>stone <strong>and</strong>"sponge-rocks"In places, <strong>the</strong> upperpart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone pancontains calcareous nodules related to formercalcareous palaeosols <strong>and</strong> rhyzoli<strong>the</strong>s. At outcrop,<strong>the</strong>se s<strong>and</strong>stones develop numerous centi- todecimetric hollows by dissolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> calciticcement (Fig. 2C). The exposed nodules aredissolved, while those isolated within <strong>the</strong> siliceouss<strong>and</strong>stone remain unaltered.Ferrantia • 44 / 200547

M. Thiry <strong>Wea<strong>the</strong>ring</strong> <strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> <strong>and</strong> related silica mobilityRIDGE"whale backs" <strong>of</strong> bare s<strong>and</strong>stonediscontinuous s<strong>and</strong> coverESCARPMENTdrawing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong> - breakup <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ridge - labyrinth-like corridorsSLOPErock chaos – dome-likeboulders with silica crusts50-100 mFig. 1: Schematic sketch showing <strong>the</strong> dismantling <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> ridges by vertical <strong>and</strong> horizontalfractures <strong>and</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dome-like shaped boulders on <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong> slopes.Dome-like <strong>morphologies</strong> with silicacrustsAer break up, <strong>the</strong> blocks acquire rounded shapes.In this way, at <strong>the</strong> ridge escarpment, <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stoneplates resulting from horizontal fracturing becomerounded at <strong>the</strong>ir upper edge, whereas <strong>the</strong>ir lowerplane show a prominent lipp-like flange. The silicadeposits formed in <strong>the</strong> fractures are put into reliefby this wea<strong>the</strong>ring.The more massive facies also round out <strong>and</strong> formdome-shaped boulders at <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridges <strong>and</strong> on<strong>the</strong> rockfall on <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>y slopes. Boulders diminishregularly in size away from <strong>the</strong> escarpment <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>domes become coated with a 0.5 to 2 cm-thick silicacrust, harder than <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone body (Fig. 2E &2F). This silica crust is restricted to <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>domes, <strong>and</strong> is lacking on <strong>the</strong> lower parts <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong>overhanging surfaces. It is put into relief by differentialalteration at <strong>the</strong> periphery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> domes.Thin sections across <strong>the</strong> silica crust show that <strong>the</strong>overgrow<strong>the</strong>d quartz grains <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone aresplit <strong>of</strong>f by tiny cracks, from 1 to 20 µm-wide,along <strong>the</strong> grain contacts, mostly parallel to <strong>the</strong> crustsurface. Quartz grains are only seldom fractured.These cracks are cemented by brown to clear opalwhich forms <strong>the</strong> harder <strong>and</strong> less alterable crust at <strong>the</strong>top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> domes. Nor empty cracks, nor cracks withclay or organic-rich illuviations are never observed.This may indicate that opal precipation itself bringsup <strong>the</strong> disjunction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> quartz grains.Polygonal dissolution groovesPolygonal networks <strong>of</strong> grooves develop on <strong>the</strong>dome flanks <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> overhanging surfaces(Fig. 2G). Such polygonal grooves never impressin <strong>the</strong> silica crusts capping <strong>the</strong> domes <strong>and</strong> coating<strong>the</strong> fractures. The network is generally isometric,forming polygones <strong>of</strong> about 5 to 10 cm in diameter,<strong>the</strong>y may become in horizontal elongated. Inplaces, <strong>the</strong> layout <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> overhanging surfaces <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone blocks, <strong>and</strong> even larger pans, clearlypoint out that <strong>the</strong>se surfaces are related to a formerl<strong>and</strong>surface supporting a paleosol which has beenstripped <strong>of</strong>f by erosion. Thus development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>polygonal networks <strong>of</strong> grooves may be relatedto processes occuring within <strong>the</strong> soil <strong>and</strong> not incontact with <strong>the</strong> atmosphere.Thin sections show development <strong>of</strong> large intergranularvoids which come with preferentialdissolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> quartz overgrowths. Thesevoids remain empty, or may contain tiny quartzchips oen blended with iron oxydes. No preexistingstructure within <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone is relatedto <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dissolution voids, nor<strong>the</strong> polygonal grooves.Never<strong>the</strong>less, if <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> polygonalgrooves indicates wea<strong>the</strong>ring-dissolution rocesses,<strong>the</strong> mechanism leading to <strong>the</strong> polygonal structureremains unknown.48 Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

M. Thiry <strong>Wea<strong>the</strong>ring</strong> <strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> <strong>and</strong> related silica mobilityA ~ 50 m B 1 m C0,1 mD 0,1 m E 0,5 m F0,5 mG0,5 mH0,1 mFig. 2: A. Aerial view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> breakup <strong>of</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone ridges with formation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rock chaos. B. Subhorizontalfractures at <strong>the</strong> ridge escarpment, <strong>the</strong> upper part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone pan is not fractured <strong>and</strong> displays dome-like<strong>morphologies</strong>. C. “Sponge-rock” resulting from <strong>the</strong> dissolution <strong>of</strong> calcareous nodules. D. Lustreous silica skin on anuneven vertical fracture. E & F. Dome-like shaped boulders capped with a well developed silica crust. G. Mushroom-likerock resulting from enhanced s<strong>and</strong>stone wea<strong>the</strong>ring at <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> former soil horizons which have beeneroded. Note <strong>the</strong> associated polygonal network <strong>of</strong> dissolution grooves. H. Dissolution bowl showing <strong>the</strong> induratedsilica lipp at its mouth.Ferrantia • 44 / 200549

M. Thiry <strong>Wea<strong>the</strong>ring</strong> <strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> <strong>and</strong> related silica mobilityDissolution bowls with silica flangeCircular decimetric-sized bowls oen form on <strong>the</strong>bare s<strong>and</strong>stones flats <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridges, as well as on <strong>the</strong>domes (Fig. 2H). These bowls are water filled <strong>and</strong>frequently overflow during autumn <strong>and</strong> wintertime. During spring <strong>and</strong> summer, <strong>the</strong>ir water levelvaries <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y oen oen oen oen dry up completly. The boom boom boom boomis generally covered by an organic-rich s<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong>water pH is about 5.The mouth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se bowls is systematicallyunderlined by an indurated roll. A silica crustalso oen oen lines <strong>the</strong> inside <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bowls, above <strong>the</strong>mean water level. The boom boom boom <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bowls, nearlyflat, is devoid <strong>of</strong> silica crust <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> contraryshows grooves about 1 cm-deep <strong>and</strong> which formpolygonal networks. In this way <strong>the</strong>se smallwea<strong>the</strong>ring features are highly interesting : <strong>the</strong>yshow in <strong>the</strong> same structure silica leaching <strong>and</strong>deposition. Some tilted blocks show several gener-ations <strong>of</strong> dissolution bowls : <strong>the</strong> younger onesbeing in "living" position, whereas <strong>the</strong> older ones,that have undergone <strong>the</strong> tipping, do not longerkeep water.<strong>the</strong> chelates formed in <strong>the</strong> top soils <strong>and</strong> also fromleaching <strong>of</strong> biogenic silica related to <strong>the</strong> vegetationcover. Silica deposition in form <strong>of</strong> opal occurs above<strong>the</strong> ground level, in <strong>the</strong> outcropping s<strong>and</strong>stones .These opal-enriched crusts form at <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>s<strong>and</strong>stone domes <strong>and</strong> around <strong>the</strong> temporary waterbowls. These deposits most probably originatefrom <strong>the</strong> pore water <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone, pore waterrising up to surface by capillarity <strong>and</strong> concentratingunder severe evaporating conditions that occur on<strong>the</strong> bare stone. The climate in <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> (meanannual temperatures <strong>of</strong> 10.2°C <strong>and</strong> 722 mm rainfallin 180 days)a priori seems not very favourable,s<strong>and</strong>stone ridge1 mSilica mobilty <strong>and</strong> wea<strong>the</strong>ringrateIn <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> Forest, <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stonesdo not display any mechanical, nor aeolian orglacial erosion feature. The <strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>s<strong>and</strong>stones mainly result from silica dissolution<strong>and</strong> to a lesser extent from silica deposition.The silica dissolution first wears away <strong>the</strong> edges<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> angular fractured blocks, which becomerounded, <strong>and</strong> lastly leads to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong>very regular dome-shaped boulders. Fur<strong>the</strong>r disso-lution arise with <strong>the</strong> hollowing <strong>of</strong> alveoles <strong>and</strong>bowls. These dissolutions occur on outcroppingblocks, above <strong>the</strong> ground level. O<strong>the</strong>r major lution features are related to <strong>the</strong> formation <strong>of</strong>overhangs which bring up mushroom-like rockstopped by larger domes (Fig. 2G), or even linearconcave features on massive s<strong>and</strong>stone pans. Theselaer laer laer laer features, which oen oen oen oen show typical polygonalgrooves, may form at depth, on buried or partlyburied s<strong>and</strong>stones, in contact with <strong>the</strong> soil. Organiccompounds in soils <strong>and</strong>pound deposits mayfavour silica dissolution <strong>and</strong> chelation (Benne (Bennedisso-1991).In parallel, quartz crystallization occurs at depth,in <strong>the</strong> fractures, oen oen oen oen toge<strong>the</strong>r with iron oxydesdeposition, beneath <strong>the</strong> discontinuous s<strong>and</strong> cover<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> podzolic soils <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ridges. Due to <strong>the</strong>lack <strong>of</strong> feldspars <strong>and</strong> clay minerals in <strong>the</strong> upperleached <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> S<strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong> deposited silicamay mainly originate at depth from destruction <strong>of</strong>s<strong>and</strong>stone boulderdissolution bowlorganic-rich soil<strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong><strong>Fontainebleau</strong> S<strong>and</strong>waterlevel0,5 mprimary shape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>s<strong>and</strong>stone block0,2 msilica depositionsilica dissolutionsilica migrationFig. 3: Sketches <strong>of</strong> silica mobility during wea<strong>the</strong>ring <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong>. Silica dissolution occurson <strong>the</strong> bare s<strong>and</strong>stone, but is enhanced in contact withsoils <strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> pounds, due to complexation with organiccompounds.50 Ferrantia • 44 / 2005

M. Thiry <strong>Wea<strong>the</strong>ring</strong> <strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> <strong>and</strong> related silica mobilitybut evaporation is never<strong>the</strong>less important on <strong>the</strong>bare s<strong>and</strong>stones that become very warm in sunnysummer days.In this manner, development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> typical<strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong>results from concomitant <strong>and</strong> contrasted wea<strong>the</strong>ringprocesses: silica dissolution during wetperiods or seasons alternates with local silicadeposition during times <strong>of</strong> dryness. Differentdissolution <strong>and</strong> precipitation mechanisms occurat depth, beneath or in soils horizons, or at <strong>the</strong>surface in contact with <strong>the</strong> atmosphere (Fig. 3).Silica dissolution is enhanced in <strong>the</strong> soilhorizons by formation <strong>of</strong> compexes with organiccompounds <strong>and</strong> lastingless <strong>of</strong> humidity. Silicadeposition occurs at depth in <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone pansby destruction <strong>of</strong> organic complexes <strong>and</strong> at surfaceby solution concentration during dryness. Never<strong>the</strong>less,<strong>the</strong> final mass balance is a massive loss <strong>of</strong>silica which is exported through groundwater.Even on <strong>the</strong> very steep <strong>and</strong> unstable s<strong>and</strong>y slopesbeneath <strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone ridge escarpements, all<strong>the</strong> s<strong>and</strong>stone blocks <strong>and</strong> boulders display <strong>the</strong>se<strong>morphologies</strong>, which moreover are in "active"position. The tilted blocks rapidely recoverequilibrium <strong>morphologies</strong>. The s<strong>and</strong>stone ering , thus is a current <strong>and</strong> rapid weath-phenomenon.ReferencesBenne Benne Benne P. C. 1991. - Quartz dissolution in organic-rich aqueous systems. Geochimica et chimica Acta 55: 1782-1797.Thiry M. & Maréchal B. 2001. - Development<strong>of</strong> tightly cemented s<strong>and</strong>stone lenses inuncemented s<strong>and</strong>: example <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Fontaine-bleau S<strong>and</strong> (Oligocene) in <strong>the</strong> Paris Basin.Journal <strong>of</strong> Sedimentary Research 71/3: 473-483.Thiry M., Paziera J.P. & Schmi Schmi Schmi J.M. 1984. - Silici-fication et désilicification des grès et des sablesde <strong>Fontainebleau</strong>. Evolutions morphologiquesdes grès dans les sables et à l’affleurement. Bull.Inf. Géol. Bassin Paris, 21/2: 23-32.Thiry M. & Schmi Schmi Schmi J.-M. 2005. - Les rochers de<strong>Fontainebleau</strong> : pourquoi et comment cesformes? Internet: hp://www.cig.ensmp.fr/hp://www.cig.ensmp.fr/hp://www.cig.ensmp.fr/hp://www.cig.ensmp.fr/~thiry/FBL_rochers/fbl-rochers-00.htmCosmo-[15.05.2005].Ferrantia • 44 / 200551

M. Thiry <strong>Wea<strong>the</strong>ring</strong> <strong>morphologies</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> <strong>S<strong>and</strong>stone</strong> <strong>and</strong> related silica mobilityRésumé de la présentationMorphologies des Grès de <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> et mobilité de silice associéeMots-clés: grès; altération; morphologie; Bassin de Paris; FranceL’altération des Grès de <strong>Fontainebleau</strong> conduit à des<strong>morphologies</strong> variées par dissolution du ciment dequartz primaire, mais aussi par précipitation de silicesecondaire. Le mouvement de la silice dans le paysagegréseux peut être suivi de l’échelle centimétrique à plurimétrique.Les fractures verticales et horizontales qui seforment en bordure des platières sont souvent couvertespar des placages de silice lustrée n’apparaissant que surles grès à l’affleurement et jamais sur les grès recoupéspar les carrières. Ces placages sont de la silice secondairedéposée en pr<strong>of</strong>ondeur dans les dalles de grès à l’affleurement,nourris par des dissolutions de silice qui se fonten surface dans les sols podzoliques. A l’affleurement, lessurfaces dénudées des grès acquièrent des <strong>morphologies</strong>caractéristiques en dôme. Les dômes montrent deux<strong>morphologies</strong> de surface: des «crevasses» polygonalesde dissolution sur les flancs des dômes et une «croûte»indurée sur leur sommet. Des dissolutions de silice sefont sur les flancs des dômes où l’eau ruisselle, alors quede la silice secondaire, sous forme d’opale, précipite sousla surface sommitale où l’eau des pores se concentre parévaporation. Des vasques de dissolution, circulaires, detaille décimétrique, se forment au sommet des platièresgréseuses et des dômes. Ces vasques, périodiquementremplies et asséchées, montrent aussi deux comportementsdistincts de la silice: dissolution sur le fond descreux et dépôt de silice secondaire dans un bourreletinduré sur l’ouverture de la vasque. Certains blocstournés montrent différentes générations de vasquesde dissolution. Les vasques les plus récentes étant enposition de «vie», alors que les plus anciennes, qui ontsubi une rotation, ne retiennent plus d’eau. Le développementde ces processus d’altération sur des pentessableuses, instables et à forte déclivité, indique que cesaltérations sont récentes et que leur vitesse d’évolutionest rapide.52 Ferrantia • 44 / 2005