Reading Informational Texts in the Early Grades - Pearson

Reading Informational Texts in the Early Grades - Pearson

Reading Informational Texts in the Early Grades - Pearson

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

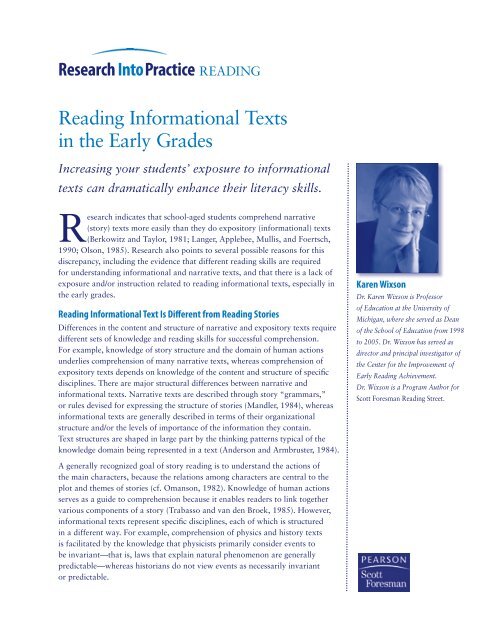

Research Into PracticeREADING<strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Informational</strong> <strong>Texts</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Grades</strong>Increas<strong>in</strong>g your students’ exposure to <strong>in</strong>formationaltexts can dramatically enhance <strong>the</strong>ir literacy skills.Research <strong>in</strong>dicates that school-aged students comprehend narrative(story) texts more easily than <strong>the</strong>y do expository (<strong>in</strong>formational) texts(Berkowitz and Taylor, 1981; Langer, Applebee, Mullis, and Foertsch,1990; Olson, 1985). Research also po<strong>in</strong>ts to several possible reasons for thisdiscrepancy, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> evidence that different read<strong>in</strong>g skills are requiredfor understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formational and narrative texts, and that <strong>the</strong>re is a lack ofexposure and/or <strong>in</strong>struction related to read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formational texts, especially <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> early grades.<strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Informational</strong> Text Is Different from <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> StoriesDifferences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> content and structure of narrative and expository texts requiredifferent sets of knowledge and read<strong>in</strong>g skills for successful comprehension.For example, knowledge of story structure and <strong>the</strong> doma<strong>in</strong> of human actionsunderlies comprehension of many narrative texts, whereas comprehension ofexpository texts depends on knowledge of <strong>the</strong> content and structure of specificdiscipl<strong>in</strong>es. There are major structural differences between narrative and<strong>in</strong>formational texts. Narrative texts are described through story “grammars,”or rules devised for express<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> structure of stories (Mandler, 1984), whereas<strong>in</strong>formational texts are generally described <strong>in</strong> terms of <strong>the</strong>ir organizationalstructure and/or <strong>the</strong> levels of importance of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>the</strong>y conta<strong>in</strong>.Text structures are shaped <strong>in</strong> large part by <strong>the</strong> th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g patterns typical of <strong>the</strong>knowledge doma<strong>in</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g represented <strong>in</strong> a text (Anderson and Armbruster, 1984).Karen WixsonDr. Karen Wixson is Professorof Education at <strong>the</strong> University ofMichigan, where she served as Deanof <strong>the</strong> School of Education from 1998to 2005. Dr. Wixson has served asdirector and pr<strong>in</strong>cipal <strong>in</strong>vestigator of<strong>the</strong> Center for <strong>the</strong> Improvement of<strong>Early</strong> <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Achievement.Dr. Wixson is a Program Author forScott Foresman <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Street.A generally recognized goal of story read<strong>in</strong>g is to understand <strong>the</strong> actions of<strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> characters, because <strong>the</strong> relations among characters are central to <strong>the</strong>plot and <strong>the</strong>mes of stories (cf. Omanson, 1982). Knowledge of human actionsserves as a guide to comprehension because it enables readers to l<strong>in</strong>k toge<strong>the</strong>rvarious components of a story (Trabasso and van den Broek, 1985). However,<strong>in</strong>formational texts represent specific discipl<strong>in</strong>es, each of which is structured<strong>in</strong> a different way. For example, comprehension of physics and history textsis facilitated by <strong>the</strong> knowledge that physicists primarily consider events tobe <strong>in</strong>variant—that is, laws that expla<strong>in</strong> natural phenomenon are generallypredictable—whereas historians do not view events as necessarily <strong>in</strong>variantor predictable.

1999, 2000). On each visit she coded, among o<strong>the</strong>r th<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>the</strong> text type ofpr<strong>in</strong>t on classroom walls and o<strong>the</strong>r surfaces, books and o<strong>the</strong>r materials <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>classroom library, and any activity dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> school day that <strong>in</strong>volved pr<strong>in</strong>t.The results showed little <strong>in</strong>formational text <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> classrooms—an average of2.6 percent of texts displayed on classroom walls and o<strong>the</strong>r surfaces, and of 9.8percent of materials <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> classroom library—on her <strong>in</strong>itial visit. The resultsalso <strong>in</strong>dicated little time dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> school day devoted to <strong>in</strong>formational text—amean of only 3.6 m<strong>in</strong>utes per day. Ano<strong>the</strong>r noteworthy f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this study wasthat children <strong>in</strong> classrooms <strong>in</strong> low-<strong>in</strong>come districts spent an average of just 1.4m<strong>in</strong>utes per day with <strong>in</strong>formational text. Not only did low-<strong>in</strong>come classroomlibraries conta<strong>in</strong> fewer <strong>in</strong>formational texts than high-<strong>in</strong>come districts, but also<strong>the</strong>y conta<strong>in</strong>ed fewer materials <strong>in</strong> general, and <strong>the</strong> low-<strong>in</strong>come class sizes werelarger, mean<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>re were fewer books per student. Duke argued that <strong>the</strong>relative scarcity of <strong>in</strong>formational texts <strong>in</strong> first-grade classrooms <strong>in</strong> general, and<strong>in</strong> low-<strong>in</strong>come classrooms <strong>in</strong> particular, may help expla<strong>in</strong> why many childrenhave difficulty with <strong>in</strong>formational read<strong>in</strong>g and writ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> later school<strong>in</strong>g—forexample, dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> “fourth-grade slump” (Chall et al., 1990).Improv<strong>in</strong>g Young Children’s Knowledge and Understand<strong>in</strong>g of<strong>Informational</strong> TextA review of <strong>the</strong> literature by Duke and her colleagues revealed studies <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>gthat young children can learn from and about <strong>in</strong>formational text if givenopportunities to <strong>in</strong>teract with this type of text (Duke, Bennett-Armistead,and Roberts, 2002, 2003b). For example, <strong>in</strong> a study where k<strong>in</strong>dergarten-agedchildren were read <strong>in</strong>formational books and <strong>the</strong>n askedto pretend to read <strong>the</strong> same books, <strong>the</strong>ir pretend read<strong>in</strong>gsshowed an <strong>in</strong>creased similarity to <strong>the</strong> adult read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> termsof a number of language features (Pappas, 1991a, 1991b,1993). In a related study, k<strong>in</strong>dergarten-aged children wereasked to pretend to read an unfamiliar <strong>in</strong>formationalbook before and after a three-month period of exposure toteachers read<strong>in</strong>g aloud o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>formational books. Children’spretend read<strong>in</strong>gs after this exposure reflected greaterknowledge of several important features of <strong>in</strong>formationaltext (Duke and Kays, 1998).Research also suggests that young children who are exposed to <strong>in</strong>formationaltexts demonstrate comprehension of <strong>the</strong> content of <strong>the</strong>se texts (Moss, 1997). Forexample, children’s journals have been observed to reflect content knowledgederived from <strong>in</strong>formational texts (Duke and Kays, 1998). In addition, children<strong>in</strong> grade 1 have demonstrated <strong>the</strong> ability to participate <strong>in</strong> sophisticateddiscussions of <strong>in</strong>formational text <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of a classroom that <strong>in</strong>cludesmany texts of this type (Hicks, 1995). F<strong>in</strong>ally, students <strong>in</strong> a first-grade classroomhave been observed to make connections among <strong>in</strong>formational books whengiven <strong>the</strong> opportunity to do so (Oyler and Barry, 1996).The evidence suggests fur<strong>the</strong>r that exposure to <strong>in</strong>formational texts improvesyoung children’s abilities to read and write <strong>the</strong>se forms of text (Kamberelis,1998; Purcell-Gates, 1988; Purcell-Gates, McIntyre, and Freppon, 1995).As part of her work with <strong>the</strong> Center for <strong>the</strong> Improvement of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong>“ Effective teachers identifyeach child’s ‘conditionsfor success’ and createflexible groups to meetthose conditions.”Research Into Practice • <strong>Pearson</strong> Scott Foresman3

“ Abandon<strong>in</strong>g traditionalstatic, ability-group<strong>in</strong>gframeworks allowsstudents of all abilities toachieve higher vocabulary,comprehension, andfluency scores.”Achievement (CIERA), Duke and her colleagues explored this effect directly byexam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g thirty first-grade classes from thirty elementary schools <strong>in</strong> six low<strong>in</strong>comedistricts randomly assigned to one of three groups (Pal<strong>in</strong>csar and Duke,2004). In <strong>the</strong> experimental group, teachers were asked to <strong>in</strong>clude approximatelyone-third each of <strong>in</strong>formational, narrative, and o<strong>the</strong>r types of texts, such aspoetry or procedural text, <strong>in</strong> classroom activities, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> classroom library, andon classroom walls and o<strong>the</strong>r surfaces. Teachers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> exposure control groupwere provided with <strong>the</strong> same amount of money and support to supplementread<strong>in</strong>g materials <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> classroom, but <strong>the</strong>re was no emphasis on diversify<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> types of texts available <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> classroom. In <strong>the</strong> third, no-treatment controlgroup, teachers were not asked to alter <strong>the</strong> materials used <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir classrooms <strong>in</strong>any way.The results of Duke’s study <strong>in</strong>dicated that by <strong>the</strong> end of grade 1, experimentalgroupchildren were better writers of <strong>in</strong>formational text than children <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>control groups, that <strong>the</strong>y had progressed more quickly <strong>in</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g level, andthat <strong>the</strong>y had shown less decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> attitudes toward recreational read<strong>in</strong>g.Experimental classes that entered school with relatively low literacy knowledgeshowed higher overall read<strong>in</strong>g and writ<strong>in</strong>g ability by <strong>the</strong> end of grade 1 thancomparable control classes. This study provides compell<strong>in</strong>g evidence of <strong>the</strong>benefits of <strong>in</strong>creased exposure to <strong>in</strong>formational text <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early grades.The Benefits of <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Informational</strong> Text <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Grades</strong>Collectively, <strong>the</strong> research on expos<strong>in</strong>g young children tomore <strong>in</strong>formational texts suggests that <strong>the</strong>re are a numberof benefits to be ga<strong>in</strong>ed from this practice. These <strong>in</strong>cludeevidence that <strong>in</strong>creased exposure is likely to:• make young children better readers and writers of<strong>in</strong>formational text• improve <strong>the</strong>ir vocabulary and comprehension skills• build <strong>the</strong>ir background knowledge• <strong>in</strong>crease motivation for read<strong>in</strong>g• improve home-school literacy connectionsAs Duke and her colleagues argue, <strong>the</strong> most obvious benefitof <strong>in</strong>creased exposure to <strong>in</strong>formational text <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> earlygrades is that it makes children better readers and writers of<strong>in</strong>formational text. However, <strong>the</strong>re is also evidence that read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formationaltexts enhances vocabulary and comprehension skills. Specialized vocabulary is akey feature of <strong>in</strong>formational text (Duke and Kays, 1998), and <strong>the</strong>re is evidencethat even young children learn vocabulary from texts, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those that areread aloud (e.g., Elley, 1989). In addition, research <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that teachersand/or parents attend more to vocabulary and comprehension when <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>gwith children through <strong>in</strong>formational texts supports <strong>the</strong> likelihood that exposureto <strong>in</strong>formational text builds vocabulary, and that general comprehension skillsmay be fur<strong>the</strong>r enhanced through <strong>the</strong>se texts (Pellegr<strong>in</strong>i, Perlmutter, Galda, andBrody, 1990; Smolk<strong>in</strong> and Donovan, 2001).4Research Into Practice • <strong>Pearson</strong> Scott Foresman

To <strong>the</strong> extent that young children’s exposure to <strong>in</strong>formational texts improves<strong>the</strong>ir ability to read and write <strong>the</strong>se types of texts as well as <strong>the</strong>ir vocabularyand comprehension skills, it is also likely to build background knowledge andpromote overall literacy development (see Dreher, 2000). Given <strong>the</strong> importanceof <strong>in</strong>formational texts <strong>in</strong> convey<strong>in</strong>g knowledge about <strong>the</strong> natural and socialworlds, this is a significant factor <strong>in</strong> prepar<strong>in</strong>g young children to read andcomprehend more advanced content-area texts.A f<strong>in</strong>al area of benefit is <strong>the</strong> potential that <strong>in</strong>creased exposure to <strong>in</strong>formationaltexts has for improv<strong>in</strong>g young children’s <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> and motivation for read<strong>in</strong>g.At least some children have high levels of <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>formational texts ortopics addressed by <strong>the</strong>m, and for those children <strong>the</strong> presence of <strong>in</strong>formationaltexts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> classroom is likely to be motivat<strong>in</strong>g. Such motivation, <strong>the</strong>n, is likelyto encourage <strong>the</strong>m to read more or to read more productively (e.g., Caswelland Duke, 1998). In addition, evidence that <strong>in</strong>formational texts are read widelyoutside of schools (Venezky, 1982) suggests that exposure to <strong>in</strong>formationaltexts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early grades may help children make l<strong>in</strong>ks between home and schoolliteracies. This may be particularly important for children from homes <strong>in</strong> whichstory read<strong>in</strong>g is uncommon (Caswell and Duke, 1998).Although research <strong>in</strong> this area is still <strong>in</strong> its <strong>in</strong>fancy, <strong>the</strong>re is already sufficientevidence to warrant <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g young children’s exposure to <strong>in</strong>formationaltexts as a means of enhanc<strong>in</strong>g a range of literacy skills. As research <strong>in</strong> this areaexpands, we are likely to learn more about which types of <strong>in</strong>formational textscan and should be <strong>in</strong>troduced at different levels of school<strong>in</strong>g, and <strong>the</strong> bestways of teach<strong>in</strong>g young children how to read <strong>the</strong>se texts. Meanwhile, let’s startread<strong>in</strong>g more nonfiction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early grades.Research Into Practice • <strong>Pearson</strong> Scott Foresman 5

REFERENCESAnderson, T. H. and B. B. Armbruster.Content area textbooks. In R. C. Anderson, J.Osborn, and R. J. Tierney (eds.), Learn<strong>in</strong>g toRead <strong>in</strong> American Schools: Basal Readers andContent <strong>Texts</strong> (pp. 193–226). Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 1984.Berkowitz, S. and B. Taylor. The effectsof text type and familiarity on <strong>the</strong> natureof <strong>in</strong>formation recalled by readers. In M.L. Kamil (ed.), Directions <strong>in</strong> <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong>:Research and Instruction (30th Yearbookof <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Conference, pp.15–161). Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: National <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong>Conference, 1981.Caswell, L. J. and N. K. Duke. Non-narrativeas a catalyst for literacy development.Language Arts, 75 (1998), pp. 108–117.Chall, J. S., V. A. Jacobs, and L. E. Baldw<strong>in</strong>.Why Poor Children Fall Beh<strong>in</strong>d. Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.Danner, F. W. Children’s understand<strong>in</strong>gof <strong>in</strong>tersentence organization <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> recallof short descriptive passages. Journal ofEducational Psychology, 68 (1976), pp.174–183.Dreher, M. J. Foster<strong>in</strong>g read<strong>in</strong>g for learn<strong>in</strong>g.In L. Baker, M. J. Dreher, and J. T. Guthrie(eds.), Engag<strong>in</strong>g Young Readers: Promot<strong>in</strong>gAchievement and Motivation (pp. 94–118).New York: Guilford Press, 2000.Duke, N. K. Us<strong>in</strong>g nonfiction to <strong>in</strong>creaseread<strong>in</strong>g achievement and world knowledge.Occasional paper of <strong>the</strong> Scholastic Center forLiteracy and Learn<strong>in</strong>g, NY, 1999.Duke, N. K. 3.6 m<strong>in</strong>utes per day: The scarcityof <strong>in</strong>formational texts <strong>in</strong> first grade. <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong>Research Quarterly, 35 (2000), pp. 202–224.Duke, N. K., V. S. Bennett-Armistead, andE. G. Roberts. Incorporat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formationaltext <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> primary grades. In C. Roller (ed.),Comprehensive <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Instruction Across<strong>the</strong> Grade Levels (pp. 40–54). Newark, DE:International <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Association, 2002.Duke, N. K., V. S. Bennett-Armistead, andE. G. Roberts. Fill<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> great void: Why weshould br<strong>in</strong>g nonfiction <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> early-gradeclassroom. American Educator, Spr<strong>in</strong>g2003 (a) http://www.aft.org/pubs-reports/american_educator/spr<strong>in</strong>g2003/void.html.Duke, N. K., V. S. Bennett-Armistead, andE. G. Roberts. Bridg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> gap betweenlearn<strong>in</strong>g to read and read<strong>in</strong>g to learn. InD. M. Barone and L. M. Morrow (eds.),Literacy and Young Children: Research-BasedPractices (pp. 226–242). New York: Guilford,2003 (b).Duke, N. K. and J. Kays. “Can I say ‘onceupon a time’?”: K<strong>in</strong>dergarten childrendevelop<strong>in</strong>g knowledge of <strong>in</strong>formationbook language. <strong>Early</strong> Childhood ResearchQuarterly, 13 (1998), pp. 295–318.Elley, W. B. Vocabulary acquisition fromlisten<strong>in</strong>g to stories. <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> ResearchQuarterly, 24 (1989), pp. 174–187.Garner, R., P. Alexander, W. Slater, V. C.Hare, T. Smith, and R. Reis. Children’sknowledge of structural properties ofexpository text. Journal of EducationalPsychology, 78 (1986), pp. 411–416.Hicks, D. The social orig<strong>in</strong>s of essayistwrit<strong>in</strong>g. Bullet<strong>in</strong> Suisse de L<strong>in</strong>guistiqueApplique, 61 (1995), pp. 61–82.Hoffman, J. V., S. J. McCar<strong>the</strong>y, J. Abbott,C. Christian, L. Corman, C. Curry,M. Dressman, B. Elliott, D. Ma<strong>the</strong>rne, andD. Stahle. So what’s new <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> new basals?A focus on first grade. Journal of <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong>Behavior, 26 (1994), pp. 47–73.Hynd, C. R. (ed.). Learn<strong>in</strong>g from text acrossconceptual doma<strong>in</strong>s. Mahweh, NJ: LawrenceErlbaum Associates, 1998.Kamberelis, G. Relations between children’sliteracy diets and genre development: Youwrite what you read. Literacy Teach<strong>in</strong>g andLearn<strong>in</strong>g, 3 (1998), pp. 7–53.K<strong>in</strong>tsch, W. and T. A. van Dijk. Towarda model of discourse comprehension andproduction. Psychological Review, 85 (1978),pp. 363–394.Langer, J. A., A. N. Applebee, I. V. S. Mullis,and M. A. Foertsch. Learn<strong>in</strong>g to Read <strong>in</strong>Our Nation’s Schools: Instruction andAchievement <strong>in</strong> 1988 at <strong>Grades</strong> 4, 8, and 12.Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton, NJ: Educational Test<strong>in</strong>g Service,1990.Mandler, J. M. Stories, Scripts, and Scenes:Aspects of Schema Theory. Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, 1984.Mandler, J. M. and N. S. Johnson.Remembrance of th<strong>in</strong>gs parsed: Storystructure and recall. Cognitive Psychology, 9(1977), pp. 111–151.Meyer, B. J. F. The Organization of Prose andIts Effects on Memory. Amsterdam: NorthHolland, 1975.Moss, B. A qualitative assessment of firstgraders’ retell<strong>in</strong>g of expository text. <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong>Research and Instruction, 37 (1997),pp. 1–13.Moss, B. and E. Newton. An exam<strong>in</strong>ationof <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formational text genre <strong>in</strong> recentbasal readers. Paper presented at <strong>the</strong>National <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Conference, Aust<strong>in</strong>, Texas,December, 1998.Olson, M. W. Text type and reader ability:The effects of paraphrase and text-based<strong>in</strong>ference questions. Journal of <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong>Behavior, 17 (1985), pp. 199–214.Omanson, R. C. An analysis of narratives:identify<strong>in</strong>g central, supportive, anddistract<strong>in</strong>g content. Discourse Processes, 5(1982), pp. 195–224.Oyler, C. and A. Barry. Intertextualconnections <strong>in</strong> read-alouds of <strong>in</strong>formationbooks. Language Arts, 73 (1996),pp. 324–329.Pal<strong>in</strong>csar, A. S. and N. S. Duke. The roleof text and text-reader <strong>in</strong>teractions <strong>in</strong>young children’s read<strong>in</strong>g development andachievement. Elementary School Journal, 105(2004), pp. 183–197.Pappas, C. C. Foster<strong>in</strong>g full access to literacyby <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation books. LanguageArts, 68 (1991a), pp. 449–462.Pappas, C. C. Young children’s strategies <strong>in</strong>learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> “book language” of <strong>in</strong>formationbooks. Discourse Processes, 14 (1991b),pp. 203–225.Pappas, C. C. Is narrative “primary”?Some <strong>in</strong>sights from k<strong>in</strong>dergartners’ pretendread<strong>in</strong>gs of stories and <strong>in</strong>formation books.Journal of <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Behavior, 25 (1993),pp. 97–129.Pelligr<strong>in</strong>i, A. D., J. C. Perlmutter, L. Galda,and G. H. Brody. Jo<strong>in</strong>t read<strong>in</strong>g between blackHead Start children and <strong>the</strong>ir mo<strong>the</strong>rs. ChildDevelopment, 61 (1990), pp. 443–453.Pressley, M., J. Rank<strong>in</strong>, and L. Yokoi. Asurvey of <strong>in</strong>structional practices of primaryteachers nom<strong>in</strong>ated as effective <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>gliteracy. Elementary School Journal, 96(1996), pp. 363–384.Purcell-Gates, V. Lexical and syntacticknowledge of written narrative held bywell-read-to k<strong>in</strong>dergarten and second graders.Research <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Teach<strong>in</strong>g of English, 22(1998), pp. 128–160.Purcell-Gates, V., E. McIntyre, andP. Freppon. Learn<strong>in</strong>g written storybooklanguage <strong>in</strong> school: A comparison of low-SESchildren <strong>in</strong> skills-based and whole languageclassrooms. American Educational ResearchJournal, 32 (1995), pp. 659–685.Schmidt, W. H., J. Caul, J. L. Byers, andM. Buchmann. Content of basal selections:Implications for comprehension <strong>in</strong>struction.In G. G. Duffy, L. R. Roehler, andJ. Mason (eds.), Comprehension Instruction:Perspectives and Suggestions (pp. 144–162).NY: Longman, 1984.6Research Into Practice • <strong>Pearson</strong> Scott Foresman

Slater, W. H. and M. F. Graves. Research onexpository text: Implications for teachers.In K. D. Muth (ed.), Children’sComprehension of Text: Research <strong>in</strong>toPractice (pp. 103–139). Newark, DE:International <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Association, 1989.Smolk<strong>in</strong>, L. and C. Donovan. The contextof comprehension: The <strong>in</strong>formation bookread aloud. Elementary School Journal, 102(2001), pp. 97–122.Ste<strong>in</strong>, N. L. and C. G. Glenn. An analysisof story comprehension <strong>in</strong> elementaryschool children. In R. O. Freedle (ed.),New Directions <strong>in</strong> Discourse Process<strong>in</strong>g(pp. 53–120) (1979).Trabasso, T. and P. van den Broek. Causalth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>the</strong> representation of narrativeevents. Journal of Memory and Language, 24(1985), pp. 612–630.Venezky, R. L. The orig<strong>in</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> presentday chasm between adult literacy needs andschool literacy <strong>in</strong>struction. Visible Language,16 (1982), pp. 112–127.Whaley, J. Readers’ expectations for storystructure. <strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Research Quarterly, 17(1981), pp. 90–114.W<strong>in</strong>eburg, S. On <strong>the</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g of historicaltexts: Notes on <strong>the</strong> breach betweenschool and academy. American Journal ofEducation, 28 (1991), pp. 495–519.Yopp, R. H. and H. K. Yopp. Shar<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>formational text with young children. The<strong>Read<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Teacher, 53 (2000), pp. 410–423.Research Into Practice • <strong>Pearson</strong> Scott Foresman 7

scottforesman.com800-552-22591-4182-0254-1 Copyright <strong>Pearson</strong> Education, Inc. 0505310