Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

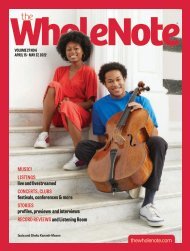

Beat by Beat | Music TheatreStratford at 60RoBERt WallaceAnniversaries are great occasions to celebrate success.Fittingly, then, the Stratford Shakespeare Festival presentsThe Pirates of Penzance, one of Gilbert and Sullivan’s mostpopular operettas, to help mark its 60th season. The festival hasa long tradition of Savoyard successes, beginning with TyroneGuthrie’s groundbreaking HMS Pinafore in the 1960s. During the1980s and 1990s, the company’s innovative productions of G&S classicsattracted a huge following, especially those directed by BrianMacDonald, the visionary Canadian choreographer who toured hisStratford production of The Mikado to London, New York, and acrossCanada to showcase the festival’s achievement. “Now once againwe’re taking a fresh approach to this beloved repertoire,”says Antoni Cimolino, the festival’s generaldirector, “one that will surely inspire a whole newgeneration of G&S fans.” Judging by the productionthat I saw in preview last month, he may be right.There’s nothing quite like a Gilbert and Sullivanoperetta, of which there are 14, all written in the late19th century for the ambitious producer, RichardD’Oyly Carte who, in 1881, built the Savoy Theatre inLondon specifically to accommodate their presentation.Although the D’Oyly Carte Opera Companyclosed in the 1980s, replications of its productionsstill appear world-wide, as do updated versions thatreinterpret the originals to meet the tastes of contemporaryaudiences. At their core, no matter whatstyle of presentation, all depict a comic view of humanfolly in nonsensical narratives that use satire,parody, slapstick and exaggeration in the service ofan energetic romp. A pre-cursor to musical comedy,the shows rely less on dialogue and more on music toconstruct characterization and propel plot — scoresadroitly composed by Andrew Sullivan to complementthe witty librettos of W.S. Gilbert. Talking aboutStratford’s Pirates, Franklin Brasz, its musical director,is quick to point out that “those witty lyrics areinextricably tied to memorable melodies.” He adds, “Iderive great pleasure from Arthur Sullivan’s wonderfullycrafted music: solo arias with gorgeous melody,Cynthia Dale as Dorothy Brockrich choral writing, deceptively clever rhythmicplayfulness … ”Stratford’s Pirates provides an excellent introduc-in 42nd Street.tion to the world of G&S by setting the show backstage at the SavoyTheatre where the audience can view the mechanics of staging aswell as its effects —the rigging, for example, that facilitates a flyingkite, or the moving flats that simulate a roiling sea. Ethan McSweeny,director of the show, and Anna Louizos, the set designer, incorporateconcepts from the contemporary “Steampunk” movement intoa design inspired by backstage images of Victorian theatre. “I wasthrilled to learn more about these retro-futurists,” McSweeny explainsof the Steampunks, “[and] their glorious expression of neo-Victoriana through the lens of Jules Verne. I think an importantaspect of Steampunk is its effort to render our increasingly invisibleand virtual world into ostensible and visible machines.”The approach works well, allowing for a stage within a stage thatdeconstructs the technology of theatrical illusion even as it createsmoments of high humour and memorable beauty. The ironies of theapproach suit the improbable story of Frederic, an upright youngman who, as a child, mistakenly is indentured to a band of piratesthat later is revealed to be more (or less) than it seems. About to turn21, Frederic believes he finally has fulfilled his obligations to hiscriminal comrades, and vows to seek their downfall, only to discoverthat, through a preposterous technicality, he must remain theirward for 63 more years. Simultaneously, he falls in love with Mabel,the comely daughter of Major-General Stanley. Bound by his sense ofduty, he convinces Mabel to wait for him faithfully … until, well, it’sbest that you find out what happens for yourself.McSweeny hews closely to Gilbert’s book and libretto, noting that“I have even gone back to some passages that were in earlier drafts.”Brasz takes more liberties, using new orchestrations (by MichaelStarobin) “that are respectful of the core G&S orchestral sound butadd new flavours by incorporating Irish whistles, bodhran drum,accordion, mandolin, even banjo.” A few costumed musicians jointhe actors onstage but, for the most part, the 20-piece orchestraperforms from its traditional location under the stage —the orchestrapit. As for the singing, Brasz confesses that “the vocal challenges are,well …operatic. With few book scenes, the cast is singing throughoutthe show. There is antiphonal chorus writing, layered themes, demandingpatter sections (and not just famously for the I Am the VeryModel of a Modern Major-General), coloratura, and cadenzas. Thevocal forces are massive and demanding but satisfying to perform;and we’ve assembled an extraordinary cast …”Indeed, Stratford’s The Pirates of Penzance is acrowd-pleaser that deserves all the accolades it isbound to receive —a show “respectful of tradition butabsolutely contemporary at the same time,” to quoteMcSweeny. Something of the same could be saidabout 42nd Street, the other musical offering thatI saw in preview at Stratford last month, albeit fordifferent reasons. There’s a symmetry between thetwo shows that becomes especially evident when oneviews them back-to-back, a connection that suggestsa possible reason for their being programmed togetherin an anniversary season. Each depicts theatrefrom a back-stage perspective that allows the audienceto see the process of making a show. WhereasMcSweeny chose the approach to help conceptualizehis innovative staging of Pirates, Gary Griffin, thedirector of 42nd Street, had no choice in the matter:the book for the musical begins and ends on-stage.42nd Street originated as a novel, written byBradford Ropes in the early 1930s. Better rememberedis the 1933 film version that ushered in thecareer of Ruby Keeler and introduced choreographerBusby Berkeley to the song-writing talents of HarryWarren (composer) and Al Dubin (lyricist). The stageversion of the story that premiered on Broadway in1980 under the direction of choreographer GowerChampion primarily uses the movie as its source,which possibly accounts for the flimsiness of thebook by Michael Stewart and Mark Bramble. Thisquintessential back-stage narrative in which anunknown chorine saves the show on opening night after its leadinglady breaks an ankle, has inspired so many imitations that its originalimpact has been lost to cliché —except for the tap dancing.“There’s an old saying that when the characters in musical theatrecan’t speak any more, they sing; and when they can’t sing any more,DAVID HOU<strong>June</strong> 1 – July 7, <strong>2012</strong>thewholenote.com 25