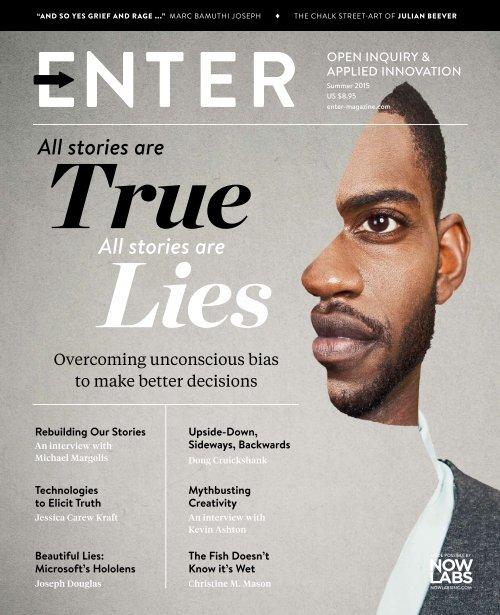

Enter Magazine, Summer 2015: All stories are True. All stories are Lies.

Journal of Applied Inquiry and Innovation. This issue examines story, storytelling, cognitive and implicit bias. Contributors include Kevin Ashton, Michael Margolis, Jessica Karew, Marc Bamuthi Joseph, and more. How do we overcome unconscious bias to make better decisions?

Journal of Applied Inquiry and Innovation.

This issue examines story, storytelling, cognitive and implicit bias. Contributors include Kevin Ashton, Michael Margolis, Jessica Karew, Marc Bamuthi Joseph, and more. How do we overcome unconscious bias to make better decisions?

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

“AND SO YES GRIEF AND RAGE ...” MARC BAMUTHI JOSEPH ♦ THE CHALK STREET-ART OF JULIAN BEEVER<strong>All</strong> <strong>stories</strong> <strong>are</strong><strong>True</strong><strong>Lies</strong><strong>All</strong> <strong>stories</strong> <strong>are</strong>Overcoming unconscious biasto make better decisionsOPEN INQUIRY &APPLIED INNOVATION<strong>Summer</strong> <strong>2015</strong>US $8.95enter-magazine.comRebuilding Our StoriesAn interview withMichael MargolisUpside-Down,Sideways, BackwardsDoug CruickshankTechnologiesto Elicit TruthJessica C<strong>are</strong>w KraftMythbustingCreativityAn interview withKevin AshtonBeautiful <strong>Lies</strong>:Microsoft’s HololensJoseph Douglas1 | ENTER magazineThe Fish Doesn’tKnow it’s WetChristine M. MasonMADE POSSIBLE BYNOWLABSINC.COM

TABLE OF CONTENTS02Rebuilding Our StoriesAn interview with Michael Margolisby Jeff Greenwald18Finding value in what’s beenthrown awayby Alan Toth0609Mythbusting CreativityAn interview with Kevin Ashtonby Jeff GreenwaldBeautiful <strong>Lies</strong>The possiblities of Microsoft’s Hololensby Joseph Douglas2021Cards Against HumanityBoldly going into markets that other peopleshunby Michael ShapiroTruth Telling TechIf the mind conceals, the body revealsby Jessica C<strong>are</strong>w Kraft10Upside-Down, Sideways,Backwards.How creating new <strong>stories</strong> spawns innovationand successThe Fish Doesn’tKnow it’s WetUnconscious bias and decision makingby Christine M. MasonOptical IllusionChalk art image by Julian Beever22Can Data Stop Self-Delusion?Top 10 uses for the quantified self14And So Yes Grief And Rage…Marc Bamuthi Joseph2316Political PostersPower to the (new) story!by Lincoln Cushing17A Curious MindThe secret to a bigger life2418by Brian Grazer and Charles Fishman (BookReview by Lisa Kay Solomon)Chaos TheoryHow monologist Mike Daisey letshis <strong>stories</strong> choose himRedemption SongEditorial & DesignChristine M. Mason // Editor-in-ChiefJeff Greenwald // Managing EditorWill Rogers // Creative DirectorJoanna Harrison // Assistant EditorKyle Sleeper // Director of OperationsConnectComments/Feedback:editor@enter-magazine.comSponsorship:sponsors@enter-magazine.comPrint Subscriptions:subscribe@enter-magazine.comPublisher<strong>Enter</strong> is published by Now Labs, Inc.www.enter-magazine.comwww.NowLabsInc.com@NowLabsInc (on Twitter)Facebook /NowLabsIncSnail Mail:80 Monte Cimas Ave,Mill Valley, CA 94941MADE POSSIBLE BYNOWLABSINC.COM2 | ENTER magazineMAGAZINEOPEN INQUIRY & APPLIED INNOVATION

LETTER FROM THE EDITORDear Reader,There is information coming at us all the time—so much of it that our brains <strong>are</strong> forcedto gloss over thousands of things in our environment just to function on a day-to-daybasis. This is a survival mechanism. The brain reasons that we need to payattention primarily to the unknown: the novel stimuli that may present a danger oran opportunity to us.Although immensely useful, this can stop us from seeing what’s present in themoment. Do you really see the details of the familiar road you drive down every day?Do you see your partner through an old lens, or as the person they’ve become? Are yousuch an industry insider that you miss threats from the outside?Our brains try to make the new conform to the known. We project what we alreadyknow onto new environments and situations, overcoating reality with our own projections.There <strong>are</strong> risks in this: We may miss key insights, trends or opportunities. We maynot hear what people <strong>are</strong> really saying, because we’re filling in the pauses with our owninternal commentary. We may be antagonized at work or play because our life experienceshave led us in different directions than our peers or partners. We might live ourlives, and build our companies, based on <strong>stories</strong> that no longer serve us.Stories provide a kind of cognitive shortcut, a shorthand communication tool thatstrips out unnecessary details and helps us learn, remember and make sense of things.They provide a great way for people to telegraph a vision (as the wonderful MichaelMargolis discusses in his interview in this issue). Simultaneously, the deification of thesound bite, the attempt to simplify complex systems into graspable narratives, can leadto oversimplification, and just plain wrong understandings.In fact, we often don’t even know we have wrong understandings — so deeply embedded<strong>are</strong> they. The Implicit Project, a long running study of precognitive bias, with over1.5 million participants, highlights this: Even when we want to be non-prejudicial, inup to 70% of daily situations, our brains autonomically register a preference — racial,gender, weight, etc — that guides many of our conscious choices.So how do we train ourselves, our teams and our organizations to identify and suspendour existing <strong>stories</strong> to make way for a new perception? How do we make space forinnovation and new insights to take root? How do we recognize a slight rumbling frombelow that might signal an impending explosion?We’re examining that question from multiple viewpoints this month. Writer DouglasCruickshank explores the real <strong>stories</strong> behind breakthrough thinking, and how insightsoccur. Jessica C<strong>are</strong>w Kraft helps us explore how technology can let us know when thebody is telling the truth. Author Kevin Ashton, who brought us “the Internet of Things,”implores a new, collective human story. And as always, our design section emphasizesemerging tech, and objects and art that blur our perceptual lines: Augmented reality,camouflage, illusion.So, what’s your story?To open, curious living,ChristineChristine Mason is the founder& CEO of Now Labs, Inc.and the editor-in-chief of <strong>Enter</strong>.3 | ENTER magazine

WHITE SPACE4 | ENTER magazine

RebuildingOUR STORIESAn interview with Michael Margolisby Jeff GreenwaldMichael Margolis is founder & CEO of Get Storied, the world’sleading school for business storytelling. An advisor to the likesof Google, Deloitte, Bloomberg, SAP, and Greenpeace, he’salso the author of Believe Me: a Storytelling Manifesto forChange-Makers and Innovators. As the Dean of StoryU, Michaelis building a “next generation curriculum for influence andtransformation through storytelling.” Dynamic, fast-spoken andcandid, he’s one of Twitter’s leading voices on storytelling, andhas been featured in Fast Company, Wired, and Inc.ENTER: In 2014, 241 books were published on businessstorytelling. Fast Company reports that more than two dozenexecutives now hold the title “Chief Storytelling Officer.” Whatdo you make of this relatively recent explosion in storytellingas a business strategy?MICHAEL MARGOLIS: It’s all part of the “humanization ofbusiness”—which includes innovation, design, social media,corporate social responsibility and workplace culture. <strong>All</strong> ofthese speak to the same fundamental issue: How do we improveour human experience? The humanization of businesshas huge implications for how we communicate with andrelate to our audience. It’s actually changing the culture ofhow we do business.ENTER: You also mention the “democratization” ofstorytelling.MM: Absolutely. That’s the role technology has in acceleratingthis process. It used to be that a few elite controlled the <strong>stories</strong>of our lives. You go back a few hundred years, it was the shaman,the priest and the elder. During the last 50 years it wasthe politician and the CEO and our p<strong>are</strong>nts. But now, becauseof technology, there <strong>are</strong> 1,001 platforms for telling our story—and less of a sense of “official” truth or knowledge.ENTER: Ben Horowitz, of Horowitz Andreessen, said that “Acompany without a story is a company without a strategy.”Who <strong>are</strong> some of the big players right now who have recentlyembraced the storytelling model?MM: AirBnB, which has gone through a major evolution overthe last couple of years. They were doing well, but also comingagainst a lot of regulatory issues and pressure from thehotel lobby. And so they’ve repositioned themselves aroundthe story of “Belong Anywhere”—which completely disruptscontinued on page 45 | ENTER magazine

WHITE SPACEand redefines “oh, you’re an alternative to a hotel.” Whatthey’re saying is “No; this is about being location independent.You’re a citizen of the world.”MM: AARP is another example. Their story, historically, was“We’re the voice and advocate for elders who don’t have avoice for themselves.” But baby boomers don’t want to hearthat story. Baby boomers haven’t met an age that they haven’tredefined in their own image! So the folks at AARP have builta new platform called Life Reimagined. It celebrates the waysthat people, age 50 and older, <strong>are</strong> approaching the next phaseof their lives. AARP’s new story is, “How do I want to rewritethe next chapter of my story?”MM: Great question. One of our mantras is “How do you bringintegrity to the process of speculation?” Because the verynotion of innovation is about the imaginal realm. It’s about avision, a dream. You’re inviting people to redefine the boundariesof what they think is possible. And so you have to orientpeople to possibility and opportunity. Then, only then, do youintroduce the obstacle that stands in the way of experiencingthat possibility.Often, our business rhetoric is built on the premise ofproblem/solution. But it’s a terrible architecture. It repelsmore than it attracts. Because the moment you start with aproblem, you’re putting people on the defensive. The simplere-framing from problem/solution to possibility/obstacle isone of the underlying principles of what we teach.ENTER: Is there a neurological basis for what makes astory work?ENTER: I find there’s a thin line between a story and a jingle.“Life Reimagined,” “Just Do It,” “Belong Anywhere...” Why dothose pass for <strong>stories</strong>?MM: Because we’re taking something incredibly complex,and distilling it down to its essence. And because in creatinga new story, you want to start with addressing “where,” not“why.” The big unanswered question in the mind of any audienceis, “Where am I? Do I belong in this story?”People <strong>are</strong> struggling to find out where they <strong>are</strong>—and thejob of good leaders and good brands is to help people locatethemselves. To give them a story they can believe in. “Yes! Iwant to be a part of that! I want to be part of Life Reimagined!I want to Belong Anywhere!”MM: The neuroscience of storytelling shows that we’re hardwiredfor narrative. We used to all tell <strong>stories</strong>, sitting aroundthe fire. These (often cautionary) tales were meant to get us topay attention, because there was danger everywhere.When you look at most classical <strong>stories</strong>, they begin bystimulating the release of cortisol, a stress hormone: Pay attention.But at the end, the story needs to have a payoff. Thisis oxytocin, the “feel good” hormone. It flows through yourblood when you experience the love of your mother, or a goodmeal. So in a classic story there’s a relationship between fightand flight and feeling good. But classical storytelling—andmarketing—overemphasizes cortisol and under- emphasizesoxytocin. We spend too much time trying to sc<strong>are</strong> people,instead of doing the things that make them feel good.There’s a deep pathology in the way we’ve built the communicationarchitecture of our culture. I see a big, big shiftunderway, where we’re learning a new way of actually structuringour <strong>stories</strong>. Where we meet people is at a place of desireinstead of a place of inadequacy—that something’s broken,and they need to fix it.ENTER: In your talks you assert the importance of Truth,Empathy and Connection. That sounds shockingly nonmanipulative.But is it actually non-manipulative? And do youreally think things <strong>are</strong> going in that direction?ENTER: Where do you draw the line between a story anda fabrication?MM: When I look at the world today, and the kinds of big,complex issues that we’re facing as leaders of organizations,the <strong>stories</strong> we have to tell can’t be wrapped up in a pretty littlebow. We can’t give people a prefabricated ending, because it6 | ENTER magazine

WHITE SPACEKevin Ashton’s Latest bookHow to Fly A Horse: TheSecret History of Creation,Invention and Discovery.,can be purchased here:http://tinyurl.com/ph9ezb38 | ENTER magazine

MYTHBUSTINGCreativityAn interview with Kevin Ashtonby Jeff GreenwaldKevin Ashton—a British-born writer, inventor and entrepreneur—has had a dizzying arc in the creative world, encompassingeverything from noodles to sensor networks. He began hisc<strong>are</strong>er as an assistant brand manager at Procter & Gamble(P&G), where his investigations into the mystery of their lipsticksupply chain ultimately led him to pursue a collaboration withMIT. There, he helped start the Auto-ID Center with professorsSanjay Sarma, Sunny Siu and researcher David Brock. The centersuccessfully created a global standard system for RFID (radiofrequency identification) and other sensors — a network thatAshton famously named “The Internet of Things.”Ashton went on to a number of high-tech start-ups, includingThingMagic, cleantech company EnerNOC, Zensi (an energysensing company, which he cofounded) and to develop the BelkinWeMo home automation system. A firebrand and wry social criticwho delights in disassembling social myths, he recently publisheda bestselling book: How to Fly A Horse: The Secret History ofCreation, Invention and Discovery.ENTER: How to Fly a Horse opens by deconstructing a popularstory about Mozart and creativity. How does this story, alongwith other myths about the creative process, hold people backfrom being more innovative?KEVIN ASHTON: In this case, as in so many others, ‘myth’ isa polite word for ‘lie’. The lie is that Mozart’s compositionsappe<strong>are</strong>d complete in his mind, and all he had to do was writethem down. It comes from a letter we have known to be fakefor 150 years—yet authors and academics keep repeating it,trying to prove that creating is a magical process conjuredup by a sort of rain dance. If you believe that, you’re going towaste a lot of time trying to learn the dance. You don’t needto: Creating is the result of work and tenacity, not magic.When you realize that everyone works the same way—includingthe people who get the most exceptional results—it’s quiteaffirming and liberating.ENTER: So what you’re saying is that you redefined yourselfbased not on what you thought creativity was, but on how itactually works.KA: More like I eventually figured out I wasn’t doing it wrong.ENTER: You’ve said that while collaboration helps the creativeprocess, “all creative work is done individually.” Can theprocess of collaboration or brainstorming actually retard thecreative process?ENTER: You’ve spoken of feeling like “a bit of a fraud…animposter.” What story about yourself did you have to rewrite inorder to make the transition you have made?KA: Imposter syndrome is quite common at places like MIT,precisely because so many of us have been led—actuallymisled—to believe that people who succeed at creating <strong>are</strong>accessing magical powers. So, when we get results throughtrying, failing, and trying again, and by showing up earlyand going home late, it can feel like brute force and cheating.KA: Probably. First, it’s a waste of time. Second, you end upwith meetings where experts who put in the hours <strong>are</strong> forcedto explain or defend things to non-experts who don’t. Third,false notions of collaboration and sh<strong>are</strong>d credit, which <strong>are</strong>common in organizations and corporations, can be souldestroyingfor the people who actually do the creating. Example:If a young, poorly-paid black woman does the creativework and an older, overpaid white man takes credit, that’sbad because it’s unfair, bad because the creative womanis less inclined to create and more likely to leave, and badcontinued on page 89 | ENTER magazine

WHITE SPACEbecause when she does leave, the person who tookthe credit is expected to create but doesn’t knowhow. The moment you recognize that creativecollaboration means well-coordinated but individuallyexecuted work, it becomes much easier to see who isactually contributing, and to reward accordingly.control, because—and I hear this one often—they“don’t like surprises.” But surprises <strong>are</strong> a natural,inevitable result of creating. If you burden yourcreative people with endless, pointless meetings,you can be sure you won’t get any surprises because nothingcreative is likely to happen.ENTER: How could this actually be implemented without beingperceived as a threat to “overpaid white men?”KA: It is a threat to overpaid white men. You cannot pursueequality unless you abandon privilege, because privilege isthe epitome of inequality. And you cannot have the most creativeorganization possible unless you pursue equality. Thatis why most organizations <strong>are</strong> not as creative as they couldbe: not because of “disruption,” or dilemmas, or paradigmshifts, or any of that other MBA jargon, but because of the entrenchedpower of privilege and patriarchy. Yes, the price youpay for equality is privilege. But the benefits—the fruits of amore creative, more inventive world—far outweigh the costs.False notions of collaborationand sh<strong>are</strong>d credit, which <strong>are</strong>common in organizationsand corporations, can besoul-destroying for the peoplewho actually do the creating.ENTER: What kinds of long-perpetuated myths (orassumptions) hold companies back from being moreinnovative?KA: In addition to the idea that everyone should sit in a roomand create together, there’s the idea that creating can be organizedto happen on some kind of schedule, through lots ofmeetings. And most of those meetings involve pre-meetingsand post-meetings where subsets of attendees <strong>are</strong> expected toplan for the planning, and review the reviews.ENTER: What drives that?KA: Often, it’s people with various management titles, whodon’t actually do creative work, trying to feel like they <strong>are</strong> inENTER: There is a whole culture of “storytelling” aroundbranding, marketing and corporate identity these days. Doyou see this as a positive development, or do you think it’san artifice?KA: It’s generally bullshit. Most of what you see about “branding”these days is the business equivalent of literary criticism:word salad from people with little practical experience.The point of branding is to solve the problem of choice: to givea potential customer a way to feel confident about a purchasewithout having to review every option. Put simply, brand isanother word for reputation. And who tells the <strong>stories</strong> that accompanyreputation? Customers; not corporations. Sure, youcan distill that, and package it some—but if the product orservice doesn’t deliver, or what you say about yourself doesn’tresonate with what existing customers say about you, you <strong>are</strong>wasting your time.ENTER: What’s the primary story we’re telling ourselves rightnow – as a civilization – that’s patently untrue?KA: One untrue story is that we’re the worst, collectively. Wehave an uneasy relationship, for example, with our technology.We shouldn’t. Creating ever-improving tools is whatmakes us human. That causes a few problems, and alwayswill (which is why everything can always be improved). But itoffers far more solutions. The power to be creative is an amazingcapability. We all have it to some degree, and we shouldcherish it.Another untrue story is that, while many people seem tothink the human race is the worst collectively, they think they<strong>are</strong> the best individually. This sense of superiority is extended(when convenient) to the groups to which they think they belong:races, for example, or regions, or nations.These two things <strong>are</strong> connected. The basic summary is, “Iam great, but look at all these other idiots.” The truth is that we<strong>are</strong> all equally amazing, equally unique and equally deservingof love and empathy, even though we have different aptitudesand tendencies and will make different contributions. That’s notjust a moral position; it’s a scientific one—we see it when we lookat the human genome. Civilization’s primary story should be,“We’re all amazing.” n10 | ENTER magazine

BITS/ATOMSBEAUTIFUL LIESThe possibilities of Microsoft’s Hololens.by Joseph DouglasIn Ray Bradbury’s classic 1950short story The Veldt, the linebetween truth and lie is lethallycrossed by two children, who bringa virtual reality scene of ravenouslions to life. Microsoft’s Hololensboasts similarly unique capabilities.Hololens harnesses light andelectricity to map holographicimages onto the material (i.e.,“real) world.Holograms, of course, <strong>are</strong> threedimensionalpictures made entirely oflight. Microsoft’s product, worn as aheadset, superimposes these pictureson the immediate environment,augmenting reality with 3D images assmall as sticky notes or as large as lions.These non-physical objects, accordingto the company, “can be viewed fromdifferent angles and distances, but theydo not offer any physical resistancewhen touched or pushed because theydon’t have any mass.”The device can bring Australia’sGreat Barrier Reef into your home,letting you explore the wonders ofaquatic flora and fauna. Woefully, ofcourse, the experience is a lie. The GreatBarrier Reef is in the Coral Sea, notin your living room. But such lies <strong>are</strong>valuable, because the Great Barrier Reefcannot fit in your home—and you cannotbreathe underwater.This new medium, when fullydeveloped, will create lies that allow us toexpand our perceptions, and experienceplaces and situations that <strong>are</strong> otherwiseinaccessible—and in some cases, shouldprobably remain so. nwww.microsoft.com/microsoft-hololensJoe Douglas is atechnologist specializingin 3D communications.He is the CEO andfounder of ImporiumInc, a stealth startupdeveloping platforms for3D experiences.@Joseph Douglas11 | ENTER magazine

FEATURE12 | ENTER magazine

Upside-Down,SIDEWAYS, BACKWARDS.How Creating New Stories Spawns Innovation and Successby Douglas CruickshankDouglas Cruickshank is the author of Somehow: Living onUganda Time, a book about his life in Africa, and two anthologiesof his earlier writing. For more information, visit his website:douglascruickshank.comAdozen years ago, I saw the extraordinarydocumentary Winged Migration. I left thecineplex asking myself, “How on earth didthey get that footage?” The camera often seemed tobe flying right next to the film’s avian stars. How couldfilmmakers get so close to wild birds?I didn’t come up with an answer because my thinkingwas limited by an internal story—an assumption— abouthow such films <strong>are</strong> made: with hidden cameras and telephotolenses. But the visionary makers of Winged Migration createda new story that never occurred to me: Don’t chase the birds;make the birds chase you. The birds were raised specificallyfor the film. They had “imprinted” on the film crew, and werehabituated to the cameras. When the birds saw their filmmaker“p<strong>are</strong>nts” they followed them – making the close-upcinematography easier and natural-looking.That’s one example of how embedded thinking—the<strong>stories</strong> we repeatedly tell ourselves of how best to do something—maybe fabrications that hobble our achievements.Reversing such thinking can enable innovation. And we cansee plenty of examples these days, from the corporate worldto art and science, of those who’ve found a better way by takingan unexpected approach to a longstanding challenge: bychanging the story.So-called “disruptive thinking” has been around fora long time. Though the term has achieved buzz phraseprominence in recent years, the process is closely tied witha more fundamental human ritual: the telling of <strong>stories</strong>, toourselves, to others, and within our corporate and innovationcultures. Reinventing an entrenched story is now celebratedas the foundation for some of today’s most successful newcompanies — brash new organizations with names like Uber,AirBnb, Spotify, Shyp, ZipCar, Indiegogo and Kickstarter,Snapchat, Lending Club, Motif Investing, TransferWise andRent the Runway, to name a dozen. These ventures <strong>are</strong> findingconsiderable success by upending convention.Arriving at solutions by creating new <strong>stories</strong> is what innovatorshave done for centuries. Now companies like Uber<strong>are</strong> applying the approach. In a 2010 post on Uber’s blog,Travis Kalanick, the company’s co-founder and CEO, recallsits origin.“Garrett Camp and I were hanging out in Paris.... Garrett’sbig idea was cracking the horrible taxi problem in SanFrancisco.” Namely, you can’t get one when you need one.Uber, with its app-centric dispatching, tracks demand in realtimeacross a city, helping riders and drivers find each otherfast. And its no-cash model makes it much safer for drivers.Kalanick says that he and Camp, now Uber’s Chairman,“thought the business was going to be pretty low-tech, mostlyoperational. Little did we know!” As of March <strong>2015</strong>, Uber wasoperating in 55 countries and more than 250 cities worldwide.continued on page 1213 | ENTER magazine

FEATUREIn December 2014 the company was valued at $40 billion.Getting around is a fundamental problem. But going instyle, without going broke, is the challenge that JenniferFleiss and Jennifer Hyman set out to solve. In 2009, Fleissand Hyman believed that high fashion could be affordable.The two decided to rewrite the old “I don’t have anything towear” story when Hyman’s sister was appalled at what she’dhave to spend for a friend’s upcoming wedding. “She wantedsomething gorgeous to wear,” reported The Muse, “but didn’twant to drop an obscene amount of money on a dress she’donly wear once.”The solution: An online service offering designer clothes forevery woman. Sounds good, but who can afford to buy designeroutfits? Who said anything about buying? Hyman and Fleiss’sRent the Runway doesn’t sell big namecouture, it rents the pricey app<strong>are</strong>land accessories. The online venturethat’s been termed “Netflix for eveninggowns,” is now valued at about$220 million.How do change-makers enabletheir unconventional thinking?Artist/engineer, Alexander Reben,whose work has been widelyexhibited and reviewed, is directorof technology and research atStochastic Labs. Though not exactlya business person, he’s immersedin invention on a daily basis. A designer of robots and otherdevices, he’s interested in “human-machine relationships.”Reben admires the “ability to walk across disciplines andboundaries, and look at the evolving patterns. By thinkingwidely — in philosophy, psychology, design, and alsoengineering and computer science — you can sidestep, hugeengineering problems—for example, by being cute.”Cute?One of the more difficult robot design problems, Rebenexplains, has been building inexpensive machines that canclimb stairs. He looked at the challenge from multiple perspectives—then built “Boxy,” a small, wide-eyed robot thatis baby seal adorable. In a childlike voice, Boxy simply askspassing humans to carry it up a nearby staircase. What hardheartedsoul could refuse?Nearly none, it turns out. “The robot leverages the person’slegs, which <strong>are</strong> made for climbing stairs,” Reben says.“What the robot uses <strong>are</strong> not expensive treads and wheels; it’sbeing cute.” This solution, he points out, “is just not the waymost people look at solving such a problem. Thinking acrossboundaries is something we’re taught not to do in school.”At the heart of manyinventive new businessesis a seemingly intractablestory, overturned by asolution so simple that noone’s thought of it.At the heart of many inventive new businesses is a seeminglyintractable story, overturned by a solution so simplethat no one’s thought of it. Take international money transfer.It’s not a sexy venture, but it became thrilling indeed whenTransferWise started offering peer-to-peer, worldwide moneytransfers at 90 percent less than conventional financial institutions.TransferWise was started by friends Taavet Hinrikusand Kristo Käärmann. As their company history tells it,“Taavet worked for Skype in Estonia, so (he) was paid ineuros, but lived in London. Kristo worked in London, but hada mortgage in euros back in Estonia.” Taavet needed pounds,Kristo needed Euros, but the exchange and transfer feeswould take a big bite of their salaries. So each month Kristodeposited pounds into Taavet’s London bank account, andTaavet put euros into Kristo’s account.“Both got the currency theyneeded,” TransferWise explains,“and neither paid a cent in hiddenbank fees.”Hinrikus’s and Käärmann’ssingular leap in thinking questionedhow the market’s dominant playershad for years been operatingsomething as wham-bam basic ascurrency exchange, while chargingexorbitantly for it. TransferWise’ssuccess highlights a weakness thatdisruptive businesses frequently exploit:an historical lack of innovation by an industry’s leaders.One of the best recipes for unconventional thinking maybe not knowing the conventional thinking. Being free of assumptionsabout the story can lead to a better result. TakeZipcar, founded in 1999 by Antje Danielson and Robin Chase,two moms whose kids attended the same kindergarten. Itcame about not because it had experts at the helm, but becauseDanielson and Chase knew little to nothing about carsharingand rental schemes when they hit on their idea: Carsoffered by the hour, near your home, with no rental agents,paperwork, gas or insurance costs. You reserve online, get inthe car and go. Zipcar raised a meager $75,000 pre-launch; itwas purchased by Avis in 2013 for $500 million cash.Indiegogo, one of the big two crowdfunding platforms(Kickstarter is the other), was founded in 2008 by DanaeRingelmann, Slava Rubin, and Eric Schell as a tool to “democratize”fundraising. <strong>All</strong> three had tried to raise money for theaterproductions, films or, in Rubin’s case, cancer research.But access to financing was woefully limited and cliquish.The old funding story, still very much alive, features one or afew big-time investors putting up a small (or not so small)14 | ENTER magazine

fortune to underwrite a project. In crowdfunding, manypeople contribute small amounts – $5, $25, $100. It flips thestory, but often provides the same happy ending. Indiegogo’supset of status quo financing has, among thousands of otherefforts, resulted in more than $12 million in support for FlowHive, an innovative beehive (yes, a beehive) and over $5million for a project to bring computer science education to“every student in every school.”Desperation is an excellent impetus for great ideas. Oneof the most widely known of the new disruptors is Airbnb,founded in 2008 by Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia, and NathanBlecharczyk. Before they came on the scene, the story wassimple: Want a place to stay in a strange city or country? Booka hotel. One day Chesky and Gebbia woke up broke, in imminentdanger of losing their SanFrancisco apartment. A conferencewas coming to the city, so theypurchased an inflatable mattress —an airbed — and cobbled togethera web site, offering breakfast anda place to sleep. “We received somuch interest that we had to buytwo more air mattresses,” Gebbiatold Fast Company. They kept theirapartment and rewrote two <strong>stories</strong>:How to cope with a rough economy(in this case, by monetizing spacein their own homes) and how tofind accommodation while traveling.Then the Airbnb founders extrapolated, extending theirsimple idea around the world. The company is now active in34,000 cities and 190 countries.Vicariously reveling in such successes is fun, yet it’salso good to look at the roles patience and perseveranceplay in innovation. Even the most astute thinkers canwaste plenty of time going down the wrong road, then suddenly...Well, let’s listen to acclaimed primatologist RobertSapolsky, Professor of Biology, Neurology and Neurosurgeryat Stanford University.For decades, the focus of Sapolsky’s research has beenstress. He’s studied its effects in animals ranging fromrats to zebras, baboons to humans. For a full year, whiledoing graduate work on the effects of stress hormones onthe brain, he’d “gotten it into my head that a characteristicof aging was going to be an inability to turn on the stressresponse.” He tried repeatedly to prove his theory, doing“frantic cartwheels of data analysis” and spending “anentire year with elderly rats.” He finally had to admit he’dfailed, and taken a year to do it.It’s also good to look atthe roles patience andperseverance play ininnovation. Even the mostastute thinkers can wasteplenty of time going downthe wrong road.Discouraged, he went off to Kenya to do fieldwork: “Threemonths of pretty much sitting by myself.” But one day,Sapolsky recalled, “it just hit me: Aging is going to be allabout not being able to turn off the stress response. Andthat turned out to be my thesis.” He’s since authored manyacclaimed, popular books, such as Stress, the Aging Brain,and the Mechanisms of Neuron Death, Why Zebras Don’t GetUlcers, A Primate’s Memoir, and several others. Deemed “oneof the finest natural history writers around” by The New YorkTimes, Sapolsky has won numerous awards, including a 1987MacArthur Fellowship genius grant. His grad school breakthroughwas brought about by being heavily invested in anidea that was entirely wrong. Alone, immersed in solitude, inthe middle of nothingness, with time to reflect, he invertedhis idea and found the right answer.<strong>All</strong> of this brings up an interestingquestion. Are we wired to avoidinvention? Is unconventional thinkingr<strong>are</strong> because going against thegrain can be risky?“I think virtually everyone hasthe capacity to do it,” Sapolsky says,“but generally that capacity plummetsafter early adulthood or lateadolescence — because that’s whenthe familiar begins to be reinforcedand pleasurable for its own sake.It’s not for nothing that The Beatleswere 20, not 40, when they inventedeverything they did.” But age is not the sole impediment.Other things get in our way too, Sapolsky says. “I think thepotential for such thinking declines with age, and it certainlydeclines with depression, stress, self-consciousness, andsocial anxiety.”The paralysis that comes with one’s fear of saying ordoing something “stupid,” he says, “can be crippling” to thekind of free, unfettered thinking that fuels productive creativity.It’s then, he notes, that we seek refuge in repetition.We tell ourselves the old <strong>stories</strong>, and we believe them, killingour creativity. But if we’re hoping to develop something trulynew — whether the perfect ending to a sonnet or a paradigmshatteringbusiness — our <strong>stories</strong> need to be written anew.Or at least turned upside down, sideways, backwards.As Keith Johnstone wrote in Impro: Improvisation and theTheater, “Sometimes <strong>stories</strong> themselves become so predictablethat they become routines. It’s no good the knight killingthe dragon and deflowering the virgin any more. Killing thevirgin and deflowering the dragon is more likely to hold theaudience’s attention.” n15 | ENTER magazine

OPTICAL ILLUSION16 | ENTER magazine

The story? A gigantic snail, slime and all, accosts a young womanon an urban bench. British artist Julian Beever specializes inmind-boggling 3-D chalk drawings, created with an “anamorphic”technique (see inset) that must be photographed from one specificangle to provide the illusion of depth. Truth and illusion coexist inBeever’s wonderful paintings—view a whole gallery of them at:www.julianbeever.net17 | ENTER magazine

ARTSAnd so yes grief and rage…Half a millennium and white supremacy replenishes itself still inthis fertile groundConcede that the black psyche might be a ventriloquist forwhite aggression, a territory for transgression in these last flushdays of Camelot…Tell me of wanting one more day to get it right…Now…Tell me of joy in the LIVING black body and how THAT matters…Tell me of the matter of the beating heart…The factors sacrosanct in the scars a soul carves in heaven’spalms as it walks earth in heaven’s shell…Tell me of skin the color of the other side of the stars, darklike the dawn that swallowed Sean Bell…How different could we be if we spoke instead of our mostexcessive expectation…in expectation that our highestselves will prevail…Could we make JOY material?…Perhaps… an arctic blast of free at last cast in the case ofliving JOY while black…— Marc Bamuthi JosephIn May <strong>2015</strong>, Marc BamuthiJoseph premiered the“Black Joy” installation forCreative Time in New York.He is currently completinga new libretto for OperaPhiladelphia while servingas Chief of Programsand Pedagogy at SanFrancisco’s Yerba BuenaCenter for the Arts.@Bamuthi18 | ENTER magazine

POLITICAL POSTERSPower to the (new) story!by Lincoln CushingPosters <strong>are</strong> synonymouswith rebellion and visualwit. They’re “ephemeral”cultural viruses that change political<strong>stories</strong> all over the world. Thesethree examples from the BayArea illustrate the hammer-tobrainmessaging that serves as ademocratic media channel, livefrom the grassroots.Rachael Romero’s 1977 linocutserved as a defiant message againstthe apartheid regime, which at thetime enjoyed the support of the U.S.government. Printed in large numbersby the worker-owned Inkworks Press, itflipped the story about the rebellion inSouth Africa. (Romero was part of thefamed San Francisco Poster Brigade.)“Gay rights <strong>are</strong> human rights”was hand printed by John Jernegan(Northern California <strong>All</strong>iance) for the1978 Gay Pride march. The simple,obvious slogan and its crude butcharming drawing reinforced themessage’s universal appeal and reframedthe LGBT struggle. Thirty-three yearslater, Secretary of State Hillary Clintonwould decl<strong>are</strong> exactly this same phrase toan audience of United Nations diplomats.Posters <strong>are</strong>n’t just vestiges of thepre-Internet world. “Homelessness: It’snot just for poor people anymore!” bythe San Francisco Print Collective wasscreenprinted in 2001. Wheatpastedall over San Francisco’s Mission districtduring the first Dot-Com gentrificationbattle, it used satire and humor toengage a local audience, and challengethe long-standing narrative of theindigent homeless. nLincoln Cushingdocuments, catalogs,and disseminates the“oppositional politicalculture” of the late20 th century. His booksinclude Revolucion!Cuban Poster Artand Agitate! Educate!Organize! – AmericanLabor Posters.@linccushing19 | ENTER magazine

BOOK REVIEWA CURIOUS MINDThe secret to a bigger life.by Brian Grazer and Charles Fishman (Book Review by Lisa Kay Solomon)Brian Grazer believes thatcuriosity is a superpower.And he has the credentialsto prove it. As a respectedHollywood producer, Grazer’s filmsand TV shows—which include Apollo13, A Beautiful Mind, Friday NightLights and 24 —have received 43Oscar and 149 Emmy nominations,generating more than $13 billion inworldwide sales.A Curious Mind: The Secret toa Bigger Life (Simon & Schuster),chronicles Grazer’s lifelong passion for“curiosity conversations.” In exchangeswith iconic leaders including FidelCastro, Colin Powell, Isaac Asimovand polio pioneer Jonas Salk, Grazeris motivated not as a Hollywooddealmaker, but by a simple wish tolearn: What makes this person tick?What brings them joy? What were themeaningful choice points along theirjourney?In Grazer’s view, curiosity is thesecret sauce that stimulates our abilityto innovate, refines those ideas withjudgment, and finds the courage toamplify them over a wide spectrum.He’s puzzled that the trait goesrelatively unheralded in our society: “Ithink that curiosity should be as mucha part of our culture, our educationalsystem, our workplaces, as conceptslike ‘creativity’ and ‘innovation.’”Grazer’s nearly religious fever forWhat makes thisperson tick? Whatbrings them joy? Whatwere the meaningfulchoice points alongtheir journey?curiosity spins throughout the book,often covering the same materialin different chapters. Yet despitehis many mentions of his prominentconversations (and his tenacity to makethem happen), the reader is left curiousabout what Grazer himself learnedfrom those exchanges. Perhaps he’ssaving those nuggets for a sequel.Grazer ultimately seems mostexcited by the notion that curiosityis a fundamentally democratic, equalopportunity skill-set. It can makeanyone a better innovator, leader,entrepreneur, public servant, studentand human being. “Curiosity is a stateof mind,” he writes. “More specifically,it’s the state of having an open mind.Curiosity is a kind of receptivity.And best of all, there is no trick tocuriosity.” nLisa Kay Solomonteaches innovation atthe California Collegeof the Art’s MBA inDesign Strategy andco-authored the bestsellingbook Moments ofImpact: How to DesignStrategic Conversationsthat Accelerate Change.@briangrazer@lisakaysolomon20 | ENTER magazine

INQUIRYFrom the set ofThe Agony and theEcstasy of Steve JobsCHAOS THEORYHow monologist Mike Daisey lets his <strong>stories</strong> choose him.One of America’s mostprolific and powerfulmonologists, Mike Daiseyignited a national controversy whenhe included elements of fiction in TheAgony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs,his journalistic account of Apple’slabor practices at the Foxconn plantin China. He has since removed theoffending elements, and allows thework to be performed royalty-free;to date there have been more than140 productions worldwide. Daiseyhas since created monologuesinspired by William Shakespe<strong>are</strong>,Cuba, Chelsea Manning, Disneylandand many other subjects. <strong>Enter</strong>asked Daisey how he decides whichsubjects to tackle.I’m seeking things that obsess me,first of all. Always. I’m lucky, because Ihave far more obsessions than will everbe possible to cover in monologues,books, or shows. Some people <strong>are</strong> lessobsessed with everything the way I am.But my obsession is a key starting point—because without the personal passiona subject won’t eventually leaven withhumor and rise.The next vector is asking myself whatmy culture needs to be talking about.Which is not the same as what it wantsto speak about—in fact, they <strong>are</strong> r<strong>are</strong>lyaligned. My show The Story of the Gungrew out of an obsession with the historyof guns in America, and the challenge oftelling a story about guns that doesn’t setoff the old triggers and get us nowhere.To tell the story so that it sounds new inour ears.As a theatrical storyteller, it’s myjob to dramatize, not document. If I hadwanted to be a traditional journalist, I’dhave done that with my life—and wouldhave been required to turn in my poetrycard and flatten my words until they fitunder the edge of a factual door. Instead,I hang my hat with the great fabulists—Mark Twain, David Foster Wallace, JosephMitchell—who valued the truth of a storyover the bones of its facts.I didn’t always understand this aboutmyself. I let one of my works, The Agonyand the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs, be usedby journalists—and that was a mistake.Journalism in America isn’t capableof telling the whole of any story, and Ilearned the hard way that I don’t wantto be in their club. There’s an old JewishIt’s my job to dramatize,not document. …to value the truth of astory over the bonesof its facts.proverb my friend recently remindedme of: “What’s truer than the truth? Thestory.” I try to remember that every day.I love my job. I’m the only one whocan do it for the <strong>stories</strong> I hear, and I feelcalled to do it, and when the <strong>stories</strong>really sing, it’s the best thing I knowhow to give. nMike Daisey’s next book isHere at the End of Empire.21 | ENTER magazine

ATOMS/BITSREDEMPTION SONGFinding value in what’s been thrown away.by Alan TothOakland-based Alan Tothis a former South AfricaPeace Corps Volunteer, anddirector of the documentaryPosh Corps.The Riverton City landfill, justoutside Kingston, Jamaica, isnotorious: a mountain of toxicgarbage that frequently catchesfire. It’s also the epicenter ofentrepreneurial recycling in Jamaica.Scavengers comb the slopes,digging out nuggets of twisted scrapmetal to cart to the nearby shantytown. The metals <strong>are</strong> sorted, andsold to Chinese corporations—and tolocal craftsmen like Tony Duncan.Tony is Rastafarian, with thick, longdreads. His craft is a family tradition,passed down to him by his father. Tonybuys scrap aluminum, and melts it downin a furnace made out of an old oildrum. He carries the molten aluminumfrom the furnace in an iron pot, andpours it c<strong>are</strong>fully into molds sculptedfrom river sand.The aluminum originated as bauxite,buried in the limestone earth of Jamaica.It was dug from the earth and processedand cast into lightweight soda pop cans. Itwas used, discarded and buried in a wastepile. Then it was dug out of this man-mademountain with eager hands, and its storyrewritten again.In minutes the cast metal cools, andTony digs it out of the mold. He holdsit out to me: a new aluminum plate,embossed with an image of Bob Marley. n22 | ENTER magazine

TECHNOLOGYTRUTH TELLING TECHIf the mind conceals, the body reveals.by Jessica C<strong>are</strong>w KraftJessica C<strong>are</strong>w Kraft is anindependent print journalistand graphic artist in SanFrancisco, specializing inhealth, education, andsustainability.We’ve all faked smiles,laughed at un-funny jokesand told white lies witha straight face. But a set of newtechnologies is ready to call our bluff.Polygraph testing, invented in 1921, wasthe original truth-telling technology.Electrodermal (EDA) sensors measuredthe electrical conductance of the skin,which varies based on moisture level(i.e., sweat). Because sweat glands <strong>are</strong>controlled by the sympathetic nervoussystem (the “fight or flight” system),EDA can detect states of arousalfrom even the tiniest amounts ofperspiration—which can be correlatedwith emotional states. But thoughthey showed promise, these early liedetectorswere too error-prone in anycrucial context.New EDA sensors, like those usedin the Empatica’s Embrace, can be wornas a wristband; they continuously trackskin sweating in combination with othermetrics to provide a steady view of thewe<strong>are</strong>r’s emotional state. From thisdata, it’s possible to extrapolate thesubject’s activities: when they wereactive, sleeping, concentrating or evenpsychologically disturbed.Bringing the polygraph into the21st century, San Diego-based NoLie MRI offers lie detection servicesusing functional magnetic resonanceimaging (fMRI). For a $5,000 fee, asuperconducting electromagnet iswrapped around the subject’s head,generating a magnetic field. This providesfeedback from brain activity in real time.The company claims that its softw<strong>are</strong> canpinpoint deception by tracking the brain’soxygenation and activity response to aseries of questions. No Lie MRI claimstheir technology is at least 90% accurate;it has already been used as legal evidence.Emotions, too <strong>are</strong> a frontier inhonesty tech. Not long ago, it seemedimpossible to translate the complexityand subtlety of facial expressions—anticipation, shock, ecstasy, infatuation orembarrassment —into raw data.That began to change in the late1970s, when psychologist Paul Ekmancreated the Facial Action CodingSystem, cataloging more than 500universal expressions. Some recenttechnologies, like Affdex’s Affectiva,focus on analyzing these microexpression,scanning facial expressionsthat <strong>are</strong> often invisible to casualobservers. Because when we lie—oreven express an inauthentic emotion—our real feelings flash on our facesbefore we assume the face we hopeothers will perceive.The newest technologies in the truthtellingfield dispense with images entirely.They use voice stress analysis (VSA): amethod for recording physiological stressresponses in the human voice.Here’s the idea. Speech is made up oftwo components: Laryngeal structuresdetermine our fundamental frequencies,while other frequencies <strong>are</strong> producedwhen air passes through the vocal cords.VSA posits that speech also produces aninaudible FM signal, called a microtremor,between 8-14 Hz (the lowest level ofhuman hearing is about 20 Hz). Thissignal supposedly gets lower when thesubject is under stress. Variation inthese microtremors can be analyzed fordeception. Some police departments,the US Department of Defense and fraudinvestigators now use VSA; there <strong>are</strong>even consumer apps available.The effectiveness of VSA hasn’tbeen decided. Early studies found thatVSA monitoring had no better resultsthan chance. But later studies did findVSA reliable and valid. One study inparticular identified extremely highstress in a terrorist’s voice just beforehe killed a hostage in an online video,comp<strong>are</strong>d to a relatively calmer vocalpattern after the killing.More research is necessary. ButVSA’s adoption by law enforcement,and its role in some recent high-profilecases (including the Aurora, Coloradoshootings) make this technology soundpromising.It’s an intriguing, almost spookyconcept. No matter what we’re saying,app<strong>are</strong>ntly, the truth is always there—as asort of sub-audible whisper. n24 | ENTER magazine

SCIENCETHE FISH DOESN’T KNOW IT’S WET.Unconscious bias and decision making.by C.M.M“Humanbeings <strong>are</strong> consistently, routinely, and profoundly biased. We not only <strong>are</strong>profoundly biased, but we also almost never know we <strong>are</strong> being biased.”– Howard J. Ross, Everyday Bias: Identifying and Navigating Unconscious Judgments in Our Daily Lives“We almost never know we <strong>are</strong>biased.” Diversity trainer and authorHoward Ross’ assertion is supportedby the massive, multiyear ProjectImplicit at Harvard University.Implicit uses response latency tomeasure autonomic bias. Images,interspersed with positive ornegative keywords, <strong>are</strong> shownon screen, and reaction timesmeasured. The bigger the differencein reaction times between 2 pairedgroups, the greater the person’simplicit bias is.More than 1.5 million people havetaken the tests at Implicit. The tests <strong>are</strong>online, which means the sample skewstoward educated, digitally enabledpeople. Still, the results <strong>are</strong> astonishing:whether on race, gender, nationality,religious affiliation or weight — ourminds have made themselves up beforeOur minds have madethemselves up beforewe even consciouslyregister a thought.we even consciously register a thought.And it’s pervasive – in every state, everypolitical group, and every economic andage group. The lowest autonomic biasscore by state in the US was 37%. That isto say, in 37% of interactions, we have anautomatic embedded preference.It’s these implicit biases that lead tomicro-inequities, prejudices, or jumpingto false conclusions on market data oraesthetic values. They <strong>are</strong> part of a largerset of mind tricks called cognitive biases,where what we see or encounter isjudged according to our prior experienceof it, and our own values. We see throughour own lenses by default — to getthe full, and therefore more accuratepicture, we have to see through the lensof others.We make suboptimal decisionswhen we allow our unconscious biasesto run the show uninterrupted. Thecounter to unconscious bias seems to beneutralization through exposure — seeingand experiencing many things that runcounter to previous programming. Thattakes conscious effort. n@howardjross @xtinem“I am biased. I am very likely wrongor incomplete in my understanding.Therefore, I actively look for moredata through new experiences andother forms of inquiry, personallyand professionally. When I find I havea bias, I will deliberately create firsthand experiences where these biasescan be challenged.”25 | ENTER magazine

TOP TENCAN DATA STOP SELF-DELUSION?Getting real time data on the health and condition of yourbody and mind has never been easier. The hardw<strong>are</strong> andsoftw<strong>are</strong> of the quantified self has arrived: Rudimentarybiological computing interfaces <strong>are</strong> either already on themarket, or in closed beta pending FDA approval. As thefield evolves, we will not only be able to track and reactwith behavior changes, but all those things we throw at ourproblems – medications and supplements and lotions andpotions – will finally have a feedback or data loop that tells uswhat’s working and what isn’t. But, so what? How will we usethis information anyway?The top 10 current applications for quantified self:1. Manage disease andhealth conditions:Monitor temperature, blood pressure and oxygenlevels – even urine analysis and other physicaloutputs. [Scanadu Scout]2. Stop accidents:Alert driving [Faurecia Active Wellness]3. Interrupt anger:Catch you before you scream. Alert we<strong>are</strong>r topre-anger changes in vitals — Anger warning signs4. Catch bipolar onsetbefore it’s a problem:Patients and doctors work together to note earlywarning symptoms and prompt a call. [Ginger.io]5. Optimize skin for beautyand product selection:A slim device by south Korea based WAY touchesyour face and sends biofeedback on what your skinneeds. [HelloWay]6. Stay hydrated:Your data show you’re constantly dehydrated, whichimpacts all body systems. iDrate reminds you to tankup all day long.7. Get honest about exercise:Movement and activity8. Reduce stress reactions:Variety of mind training and meditation apps <strong>are</strong> atyour disposal.9. Sleep better:Your pillow can help you change position, monitoractual amounts of sleep by phase – necessary foroptimal health.10. Change your overallconsumption:When your data is tracked and measured, andespecially when it’s communicated in the context ofyour neighbors’ behaviors. For example, when utilityconsumption was show relative to neighbors’ data,energy consumption went down 27%.Conclusion:For those who see their body and mind as an organic machine,where actively using data over time to manage inputs andactivity can lead to an optimized state and optimal overalllife performance, looking at hard facts is a welcome tool inimprovement.The quantified ‘me’ may be improved if it’s thought ofas the quantified ‘we’: The data loop gets stronger whenbenchmarked, sh<strong>are</strong>d and mined across many people, andwhen sh<strong>are</strong>d between the “self-healther” and their medicalpractitioners. We can fearlessly look at our real data, and useit to change our behavior. n@quantifiedself26 | ENTER magazine

Diversity drives performance.Companies in the top quartile of racial and gender diversity<strong>are</strong> also the best performing companies in terms of Returnon Equity, or financial performance. Conversely, companiesin the bottom quartile on diversity also <strong>are</strong> at the bottom offinancial performance.Organizations have been trying for years to advance andpromote diversity through aw<strong>are</strong>ness, training and mentorship,with moderate success. What is limiting progress?Recent findings show that much, if not most, of bias in organizationsisn’t intentional*. Most bias is pre-cognitive, implicitand unconscious: opinions and reactions <strong>are</strong> formed beforewe even become aw<strong>are</strong> of them. No amount of aw<strong>are</strong>nessand diversity training overcomes this underlying constraint.Even organizations with the best intentions to be fair remainsteeped in unconscious bias.• What can be done?• How do we counter unconscious bias at work?• How do we recruit and retain the absolute best talent, andin the process advance a more equitable workplace?• Can new discoveries in science and technologyoffer a solution?UnBias is a 6 month project investigatingthis question:What emerging tools, technologies,scientific discoveries and practicalapproaches might be applied to thepersistent problem of unconsciousbias in hiring, development,promotion and pay?Areas of investigation will include:■■■■■■■■■■■■Recognizing and countering cognitive bias andautonomic preferenceNeuroscience and perceptionVisual and social signal processingBid data analysis for identifying top socializersBehavior modification toolsSelf aw<strong>are</strong>ness tools and measurementdevices, including Quantified SelfWorking with scientists and technologists from around theworld, in university labs and commercial entities, the UnBiasproject is assembling the most promising approaches tocountering racial and gender bias in the workplace, andidentifying where they can be applied in organizations.■■Low resolution techniques and experiments* See Implicit Project: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicitTo sponsor UnBias project, or to learn more about our working group,contact: Unbias@nowlabsinc.com or call 415-471-7010.27 | ENTER magazine

Your perspectiveon life comes fromthe cage you wereheld captive in.— Shannon L. AlderMADE POSSIBLE BY1 | ENTER magazineNOWLABSINC.COM