FINGERPRINTS of the Cosmos - Reg Morrison

FINGERPRINTS of the Cosmos - Reg Morrison

FINGERPRINTS of the Cosmos - Reg Morrison

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

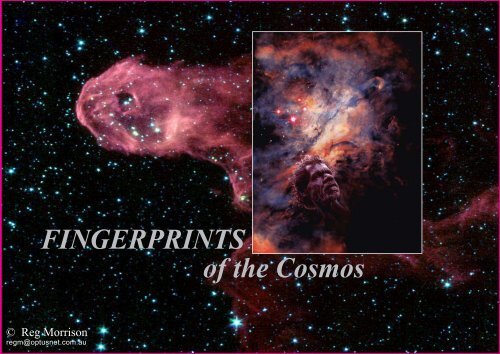

<strong>FINGERPRINTS</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Cosmos</strong>© <strong>Reg</strong> <strong>Morrison</strong>regm@optusnet.com.au

<strong>FINGERPRINTS</strong> OF THE COSMOS‘The cosmosspeaks to usin patterns’Heraclitus, 2,500 BP.Chaotic entropy within a soap film.Our universe is a <strong>the</strong>rmodynamic system and its patterns <strong>of</strong> energy flow are inherentlychaotic and fractal.* Everything that we see around us expresses this cosmic characteristicin every aspect <strong>of</strong> its existence, regardless <strong>of</strong> scale. Our brains respond instinctivelyto <strong>the</strong>se fractal patterns and our eyes trace over <strong>the</strong>m with pleasure, essentially because<strong>the</strong>y are embedded in every fibre <strong>of</strong> our being. In <strong>the</strong>m, we recognise ourselves.*CHAOS THEORY, as propounded by Edward Lorenz in 1963.

Entropy’s FingerprintsMicro-tubules,within a cell.Typhoon, NASA satellite imageWhirlpool Galaxy (Hubble image, NASA)Cosmic entropy takes many forms, but it is most flamboyantly displayed in Earth’s wea<strong>the</strong>r systems and cloudpatterns. The key characteristic <strong>of</strong> entropy is <strong>the</strong> repetition <strong>of</strong> its basic structures at all scales <strong>of</strong> magnitudefrom <strong>the</strong> cosmic to <strong>the</strong> micro-cosmic, from galaxies to intra-cellular structures. In short, it is FRACTAL.

HYDROGEN IN ACTIONWaterfall, Milford Sound, NZ.Solar ‘Moss’, precursor to a hydrogen-fuelled storm on <strong>the</strong> Sun (NASA image).‘Flowstone’, shaped by hydrogen’s oxide, water. NZ.

Entropy’s FingerprintsIn order <strong>the</strong>re is Chaos:in Chaos <strong>the</strong>re is order.Computer-generated fractals. (Peter F. Allport)Fractal growth in a foliose lichen(with reproductive spore cups),Cradle Mountain, Tasmania.

ENTROPY: CHAOTIC AND FRACTALThe chaotically fractalnature <strong>of</strong> entropy typifiesall cosmic structures, bothanimate and inanimate.When prolonged entropyunveils more durablestructures beneath <strong>the</strong>surface, <strong>the</strong>se structurestoo, frequently display astriking similarity.Cow spine, Strzelecki Desert, SA.Fijords and eroded folds in north-western Iceland. (NASA satellite image)

Entropy: Chaotic and FractalThe cosmos leaves its clearest imprints on our planet in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> impact scars suchas Gosse Bluff in central Australia. This crater-like structure is <strong>the</strong> eroded remains <strong>of</strong>a deep crustal bruise left by <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> a giant meteorite some 142 million yearsago. Such impacts are accurately replicated every time a raindrop hits a body <strong>of</strong> water.Gosse Bluff represents <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rebound splash shown in <strong>the</strong> final frame<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> series at right. The up-turned collar <strong>of</strong> hard marine sandstone that now forms<strong>the</strong> walls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> amphi<strong>the</strong>atre originally lay more than two kilometres underground.The modern stucture has been unear<strong>the</strong>d by massive erosion.Aerial: Gosse Bluff, Central Australia (NT).

Entropy: Chaotic and FractalEROSION IS FRACTALRIGHT: This scalloped escarpmentis <strong>the</strong> erodededge <strong>of</strong> a massive anticlinalfold in central Australia. Itoriginally formed <strong>the</strong> bed<strong>of</strong> a sea corridor bisecting<strong>the</strong> continent more than600 million years ago.Aboriginal legends namethis fractally scalloped escarpment<strong>the</strong> ‘place <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Dancing Women’.Fluvio-glacial strata, Poole Range, WA.‘Dancing Women’, western MacDonnell Ranges, NT.LEFT: Looking like <strong>the</strong> fossilised scales <strong>of</strong> a gigantic reptile thisthick sheet <strong>of</strong> unlayered sediment was dumped by a torrent<strong>of</strong> meltwater pouring from beneath a glacier in <strong>the</strong> ice-cappedsou<strong>the</strong>rn Kimberleys some 270 million years ago.

Entropy: Chaotic and FractalTHE PRODUCTS OF EROSION ARE FRACTALIlmenite and rutile sand, Fraser Is. QLD.Sand dunes on Mars (NASA image)Dry sand weeps down damp dune-face, Wilson’s Prom. VIC.

Entropy: Chaotic and FractalAerial: L. Lefroy, WA.The fractal patterns that characterise <strong>the</strong>eroded landscapes <strong>of</strong> Australia’s arid zone areechoed in <strong>the</strong> petroglyphs (LEFT) that werechipped into <strong>the</strong> rocks by <strong>the</strong> land’s first humancolonists more than 20,000 years ago.Rock engraving, Pilbara, WA.Strzelecki Desert, SA.

LIFE TOO, IS FRACTALLife is explicitly fractal, right down to its molecular base.Genetic material replicates continuously, enabling speciesto grow and reproduce with astonishing fidelity.RIGHT: This is <strong>the</strong> growth pattern <strong>of</strong> colonial bacteria.(Photo: Eshel Ben-Jacob, Tel Aviv University, Israel.)LEFT: A computer generatedfractal pattern.(Photo: Peter F. Allport.)BELOW: Seen from <strong>the</strong> air,coral reefs typify <strong>the</strong> chaoticand fractal nature <strong>of</strong> all life.Aerial: Great Barrier Reef, QLD, Australia.Colonial bacterium Paenibacillus dendritiformis.

Life is FractalRIGHT: Even life’s oldest tangible traces are fractal. Buriedand fossilised during a process <strong>of</strong> branching, <strong>the</strong>selayered deposits were left along an Australian shorelinealmost 3.5 billion years ago by colonies <strong>of</strong> photosyn<strong>the</strong>ticmarine bacteria.BELOW & BOTTOM RIGHT: The stromatolites that line <strong>the</strong>shores <strong>of</strong> Shark Bay on Australia’s west coast are beingbuilt by descendants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bacteria that built <strong>the</strong> fossil.Fossil stromatolites, Pilbara, WA.‘Live’ stromatolites, at high tide, Shark Bay, WA.‘Live’ stromatolites at dawn, low tide, Shark Bay, WA.

Life is FractalRIGHT: These patternswere created by a network<strong>of</strong> vascular bundlesthat formed <strong>the</strong> trunk<strong>of</strong> a banksia tree growingbeside an estuary insouth-eastern Australia.They distributed waterand nutrient throughout<strong>the</strong> tree in <strong>the</strong> years beforeit died and becamedriftwood.Driftwood, Banksia sp., south-eastern Australia.Skeleton <strong>of</strong> a sea urchin (Echinometra mathaei), Australia.LEFT: The orderly array <strong>of</strong> ball joints that once attacheda forest <strong>of</strong> spines to <strong>the</strong> skeleton <strong>of</strong> an echinodermepitomises <strong>the</strong> fractal nature <strong>of</strong> all organic deposition,and <strong>the</strong>reby, <strong>of</strong> all metabolism and growth.

Life is FractalLife is FractalTadpoles in eggmass <strong>of</strong> Brown-striped frog, Sydney.Complex ‘hand’ weapon <strong>of</strong> a Net-Casting spider, Sydney.Wings <strong>of</strong> a phasmid (leaf-insect), Sydney.

Life is FractalA peacock’s tail.Sori on fern frond (Cyrtomium falcatum).Wing fea<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> a Great Argus pheasant (Argusianus argus).

Life is FractalBones are <strong>the</strong> internal deposits <strong>of</strong> calcified ‘waste’ that accumulatein <strong>the</strong> bodies <strong>of</strong> vertibrates when nutrient is extracted from food.Such deposition, like that <strong>of</strong> erosion sediment, is inherently chaoticand fractal, and occasionally rippled like beach sand (RIGHT).Bone deposit in a fish head.Skeleton <strong>of</strong> a Kangaroo, Strzelecki Desert, SA.

Life is FractalThe patterns <strong>of</strong> energy flow that determine<strong>the</strong> pigmentation in a tiger’s fur are fractallyrelated to those that determine <strong>the</strong> flow <strong>of</strong>spring-water over black ilmenite and rutilesands on <strong>the</strong> beaches <strong>of</strong> Fraser Island andCooloola in south-eastern QLD. Such powerfulflows <strong>of</strong> kinetic energy are inherentlyChaotic, fractal and sigmoidal …

SIGMOIDSA ‘sigmoid’ is so called because it resembles<strong>the</strong> ‘S’ shape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Greek letter ‘sigma’.BELOW: Sigmoidal disturbances on <strong>the</strong> surface<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sun commonly preceed <strong>the</strong> giganticeruptions <strong>of</strong> solar energy known as sunspots.RIGHT: The uncurling <strong>of</strong> a new fern frond similarlyheralds an eruption <strong>of</strong> metabolic energyfrom within <strong>the</strong> body <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fern.A solar ‘Sigmoid’ (Yang Liu, University <strong>of</strong> Tokyo).King fern (Angiopteris evecta), Fraser Island, QLD.

Tree-fern fronds (Cya<strong>the</strong>a sp.) uncurling on a digital background by S. Geier (http://www.sgeier.net/fractals/indexe.php)

BRANCHING SIGMOIDSA common hallmark <strong>of</strong> Earthly entropy appearsin <strong>the</strong> dendritic (branching) patternsthat characterise powerful energy flows inenvironments <strong>of</strong> grossly different densityand texture. The energy flows <strong>the</strong>mselvesare invariably expressed in sigmoidal curves.Similarly dendritic patterns characterisesevery nerve, blood and lymph system in <strong>the</strong>human body.Aerial: Tidal drainage, Talbot Bay, Kimberley, WA.Nullarbor Plain, WA.

SigmoidsDead mulga woodland, Finke, NT.Fungal hyphae beneath Eucalyptus bark.Tree-like tentacles <strong>of</strong> a holothurian, Great Barrier Reef, QLD.

SigmoidsPerhaps <strong>the</strong> most elegant example <strong>of</strong>sigmoidal growth in <strong>the</strong> plant world isdisplayed by <strong>the</strong> sensuously muscularGimlet Gum (Eucalyptus salubris), whichis endemic to <strong>the</strong> Kalgoorlie-Norsemanregion <strong>of</strong> Western Australia.

THE HUMAN FACE OF COSMIC ENTROPYOf fractals, sigmoids, and our genetic attraction to <strong>the</strong>m.Skull: Homo habilis (KNM-ER 1470), Africa.Brain: Homo sapiens (not to scale).

As biological extensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Earth’s crust, we too, are cogs in<strong>the</strong> cosmic machinery <strong>of</strong> entropy, so we are shaped and driven by<strong>the</strong> same chaotic and fractal patterns <strong>of</strong> energy flow that orchestrate<strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> universe. Since we require energy to live, weare inevitably intrigued by its sources. Consequently, <strong>the</strong> shapethat is most significant for us is <strong>the</strong> sigmoidal curve—a curve thatcommonly flows from an energy source, or into an energy sink.Bathurst Island, NT.

Seeking <strong>the</strong> sigmoidSince smooth sigmoidal curves invariably signify powerful flows <strong>of</strong>kinetic energy, <strong>the</strong>y coincide with nourishment and growth and areinherently attractive to human genes.Our devotion to <strong>the</strong>sigmoid begins veryearly … and lasts alifetime!Dani, Sydney.

Seeking <strong>the</strong> sigmoidAs far as adults are concerned <strong>the</strong>sigmoid is <strong>the</strong> source <strong>of</strong> all physicalbeauty. It resides in lips, eyes,ears, hair, feet, hands, torso andlimbs.And wherever suchcurves appear in sexually maturebodies <strong>the</strong>y not only signify healthand vitality, <strong>the</strong>y double as <strong>the</strong>icons <strong>of</strong> reproductive viability—<strong>the</strong>y are ‘sexy’.

Seeking <strong>the</strong> sigmoidSydneySydneyRuth, Perth

Seeking <strong>the</strong> sigmoidSylvia, Perth.Trevor, Perth

Seeking <strong>the</strong> sigmoidAnd when we try to ornamentour sigmoidal bodies in orderto enhance our tribal statusand reproductive viability, ourgenes instruct us to ‘choose’spiral, circular and sigmoidaldecorations.Kintore, NT.Reveller, Sydney.

Seeking <strong>the</strong> sigmoid‘Butterfly’, Perth.Maree, Perth.

THE HUMAN FACE OF CHAOTIC ENTROPYAs entropy begins to take its toll, however,<strong>the</strong> smooth sigmoidal curves <strong>of</strong> youth shrivelinto lea<strong>the</strong>ry folds, <strong>the</strong> skin becomes a chaoticmoonscape <strong>of</strong> creases, craters and scars, and<strong>the</strong> skeletal framework begins to show.Linda, Perth.A farmer, WA.

The human face <strong>of</strong> entropyThe process <strong>of</strong> chaoticentropy <strong>of</strong>fers one peculiaradvantage to ourspecies. The 42 musclesin <strong>the</strong> human face areable to assemble some7,000 different expressions,and <strong>the</strong> lines thataccumulate about <strong>the</strong>ageing face, allow it toconvey a range <strong>of</strong> unspokencommunication thatextends far beyond <strong>the</strong>capabilities <strong>of</strong> youth.Anzac Day, Sydney.

The human face <strong>of</strong> entropyAnnie, Wilcannia.

Born <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ash <strong>of</strong> burnt-out stars, and shaped and driven as we are by <strong>the</strong> molecular code <strong>of</strong> DNA,we are intimately related to all life, to <strong>the</strong> sea that nurtured it,and to <strong>the</strong> rocks that gave it refuge.Moonlight on Bunker Bay, WA.END

CHAOTIC FRACTALSAll <strong>the</strong>rmodynamic entropy is inherently chaotic and fractal and is determined byrepetitive feedback (iteration) within kinetic energy gradients.Fractal patterns have been recognised as a primary characteristic <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> naturalworld for at least 2,500 years (see Heraclitus quote, p.2). Never<strong>the</strong>less, such patternswere not explored in much detail until <strong>the</strong> early 1960’s when, with <strong>the</strong> aid <strong>of</strong>computers, meteorologist Edward Lorenz began to analyse <strong>the</strong> iterative and fractalnature <strong>of</strong> wea<strong>the</strong>r patterns. He presented his research in 1963 in a short, little-notedpaper entitled “Does <strong>the</strong> flap <strong>of</strong> a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set <strong>of</strong>f a tornado inTexas?”. Lorenz’ proposition, which later became widely acclaimed as Chaos <strong>the</strong>ory,has also become known as <strong>the</strong> Butterfly Effect.Extensive research has since revealed chaotic ‘order’ in such diverse phenomenaas <strong>the</strong> folds in filo pastry, <strong>the</strong> dripping <strong>of</strong> taps and <strong>the</strong> beating <strong>of</strong> hearts. (Preciselyregular heartbeats signal a life-threatening lack <strong>of</strong> bodily feedback: chaotic heartbeats,though slightly irregular, tend to be synonymous with good health.)For those seeking more information on chaos and fractals:http://www.imho.com/grae/chaos/chaos.htmlhttp://math.rice.edu/~lanius/frac/http://images.google.com/images?q=mandelbrot&hl=enhttp://www.peterallport.com/

Biographical noteOriginally a West Australian newspaperman, <strong>Reg</strong> <strong>Morrison</strong>is now a Sydney-based writer-photographer who, for <strong>the</strong>past 25 years, has specialised in environmental and evolutionarymatters.His latest book, Australia’s Four-Billion-Year Diary,compresses <strong>the</strong> evolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> continent, its plants andanimals, into twelve ‘monthly’ episodes, and is essentiallydesigned for High School use. (Sainty & Associates, 2005)<strong>Reg</strong>’s o<strong>the</strong>r recent book, published in 2003 by NewHolland, Sydney, under <strong>the</strong> title Plague Species: Isit in our Genes?, summarises <strong>the</strong> massive impactthat humans have had on <strong>the</strong> biosphere, and explores<strong>the</strong> evolutionary origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> behaviour thatproduced this impact. It was originally published in1999 by Cornell University Press, New York, under<strong>the</strong> title The Spirit in <strong>the</strong> Gene.O<strong>the</strong>r books by <strong>Reg</strong> <strong>Morrison</strong>:Australia, Land Beyond Time, New Holland Publishers, 2002(original title: The Voyage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ark, 1988).The Great Australian Wilderness, Phillip Ma<strong>the</strong>ws Publishers, 1993.Australian’s Exposed, Paul Hamlyn, Sydney, 1973.

The images in this collection are subject to <strong>the</strong> author’s copyright unlesso<strong>the</strong>rwise indicated.Reproduction rights and photographic prints may be obtained via emailapplication to:regm@optusnet.com.auWebsite: www.regmorrison.id.au