Download

Download

Download

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

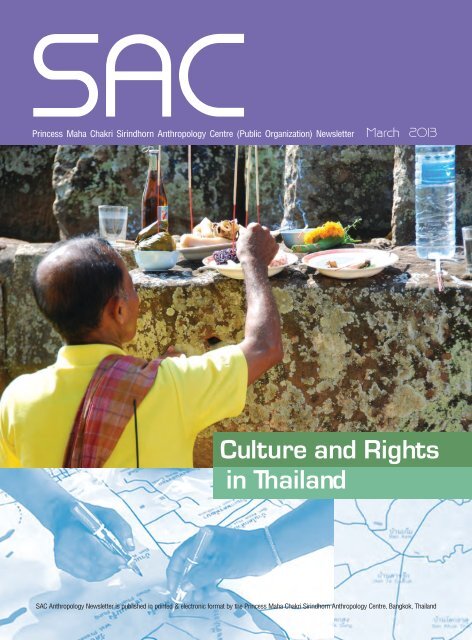

Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre (Public Organization) Newsletter March 2013Culture and Rightsin ThailandSAC Anthropology Newsletter is published in printed & electronic format by the Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, Bangkok, Thailand

SACNewsletterIntroductionSAC Newsletter IntroductionCulture and Rights in ThailandOver the past two decades, the right to culture and the right to “belong to” a culture hasbecome an increasingly important topic in contemporary academic debate. Whereashistorically, human rights discourses have focused on the rights of the individual, in recentyears, “culture”—particularly the right to ‘belong to’ a culture—has become a focus of rightsclaims. As enshrined in a number of international legal instruments, most recently the 2001Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, “cultural rights are an integral part of human rights,which are universal, indivisible and interdependent.”International cultural rights instruments aim to encourage states to recognize the value ofdiversity and recognize the “group rights” of minority and indigenous groups. In many parts ofthe world, these groups at the sub-national level are asserting their rights, utilizing a distinctivelanguage, tradition, locality, race, ethnicity or religion as a basis for claims to land, environmentalprotection, political autonomy, employment and the repatriation of traditional cultural resources.Since 2009, the SAC’s Culture and Rights in Thailand (CRT) project has sought to uncover howthese complex issues are being explored and negotiated within the context of Thailand. Amulti-year, and multi-sited research project, CRT endeavored to answer the following questions:• How is the concept of cultural rights defined and understood in Thailand?• Who “owns” and/or controls cultural heritage, and through what mechanisms?• Which groups are using the discourse of cultural right to stake claims and why?This issue of the SAC Newsletter features several of the projects undertaken as part of theCulture and Rights in Thailand project, offering a glimpse of what’s to come in the forthcomingvolume, Rights to Culture: Heritage, Language and Community in Thailand, edited by Dr. CoeliBarry and published by Silkworm Books (2013) .As always, we welcome your comments and feedback!Alexandra DenesEditor

Director’sBiographyThe Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre is pleased to welcome anew director, Dr. Somsuda Leyavanija, who joined the SAC in 2 January2013. Originally from Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya province, Dr. Somsuda hadthe opportunity to see many parts of Thailand as a child, as her father wasengineer for a sugar refinery with operations in different locations. Her motherwas an English teacher who always encouraged Dr.Somsuda to learn Englishthrough books and magazines, which equipped her with an interest and giftfor language-learning ever since. She also credits her experience in boardingschool for teaching her to be “strong, orderly, tolerate, independent and capableof solving problems at hand.”After completing high school level from Rajini School, Dr. Somsudajoined an AFS (American Field Service) program and spent a year as an exchange student in U.S.A. She thencontinued her undergraduate study at the Faculty of Archaeology, Silpakorn University. Later, she was granted theAnanda Mahidol Foundation scholarship and pursued her Master’s degree in Anthropology at the University of Otagoin New Zealand, graduating in 1979. In 1988, Dr. Somsuda completed a Ph.D. degree in Prehistory from the AustralianNational University with the Ananda Mahidol Foundation scholarship as well.Her first duty after the completion of her Ph.D. degree was to serve as an archaeologist at the Division ofArchaeology, Fine Arts Department. At that time, she was responsible for the preparation of World Heritage nominationfiles for three cultural heritage sites: namely, Ban Chiang, Sukhothai and Ayutthaya, and her work was successfullyaccomplished, as they were listed by UNESCO as “World Heritage” sites. She was later assigned to a bureaucraticposition at the Division of Archaeology, where she traveled with the director and head archaeologist to work in manydifferent regions. Her work during this period included research at the Ban Chiang heritage site and a historical areasstudy project in Nakhon Nayok province. Moreover, in addition to being consistently active in Thailand’s archaeologicalsector, Dr. Somsuda has had many opportunities to experience different types of work, since she has taken upvarious positions such as Secretary of the Director General of the Fine Arts Department, Director of the Chiang MaiNational Museum, Director of the Office of Archaeology, Director of the National Archives of Thailand and DeputyDirector General of the Fine Arts Department. Her last position before joining the Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre wasDirector General of the Fine Arts Department, where she fully dedicated her archaeological experiences in lookingafter Thailand’s heritage. Especially in the time of natural disaster, Dr. Somsuda always paid close attention to thesituation, monitoring the recovery of archaeological sites in the disaster areas. Moreover, Dr. Somsuda was appointedby the Government as a representative of Thailand on the World Heritage Committee and took part in the 17th GeneralAssembly of State Parties to the World Heritage Convention and the 35th UNESCO General Conference.Apart from the administrative tasks, Dr. Somsuda also produced a wide range of academic literatures that aresignificant for Thailand’s archaeological research and study. She played a vital role in compiling and translating theFine Arts Department’s books and documents, namely “Theories and Practices for the Preservation of Monuments andArchaeological Sites”(หนังสือทฤษฎีและแนวปฏิบัติการอนุรักษ์อนุสรณ์สถานและแหล่งโบราณคดี), “The Fine Arts DepartmentStandards and Practices in the Management of Archaeological Sites, Archaeology and Museums”(หนังสือร่างมาตรฐานและแนวปฏิบัติของกรมศิลปากรในการจัดการโบราณสถาน โบราณคดีและการพิพิธภัณฑ์), “Management Guidelines for WorldHeritage Sites” (หนังสือแนวทางการจัดการโบราณสถานในบัญชีมรดกทางวัฒนธรรมของโลก) and “Mexico City Declarationon Cultural Policies of UNESCO” (หนังสือการประกาศนโยบายด้านวัฒนธรรมของนครเม็กซิโกขององค์การยูเนสโก).

Engaging Cultural Rights in Research,Practice and Policy:Lessons from the Culture and Rightsin Thailand ProjectFeatured Post:by Coeli BarrySenior Advisor, Cultural Rights Forum, Lecturer at the Institute of Human Rights and Peace Studies, MahidolUniversity. Coeli Barry can be contacted via the Institute at http://www.ihrp.mahidol.ac.th/Cultural institutions around the world today are facing challenges in terms of how theypreserve and disseminate knowledge about cultural heritage. Over the past 20 years, changes ininformation technology and a greater appreciation of the power of representation are promptingpublic institutions to re-assess policies and guidelines about who should have access to existingholdings and how new information should be gathered and made available to the public. Institutionsincreasingly find themselves facing decisions about the ethics of making digitized material morewidely available to source communities, as well as about how anthropological materials shouldbe collected and displayed.In some cases, cultural institutions, such asmuseums, libraries, archives and research centers,have developed restricted access protocols and digitalrepatriation policies in response to the demands ofcommunities to either return items or facilitate greatercommunity access. Even if cultural institutions are notdirectly challenged by community claims, they may still takepart in the widespread and lively debate in professionalgatherings, scholarly outlets and on the internet aboutthe most suitable institutional policies that can takeaccount of the interests of the ‘culture bearers’ alongsidethose of the public more widely. In fields as diverse asmuseum studies, archaeology, knowledge management,heritage studies, visual arts, and anthropology, there isan increasing awareness of the potential for innovationin how anthropological knowledge is gathered, used anddisplayed.One framework that is emerging as particularlysalient for practitioners and scholars alike is a rightsbasedapproach to heritage management. This approachdraws on international human rights conventions thatpromote the notion of ‘a right to culture’ in a general sense,as well as those documents that address cultural rightsfor minorities, or the rights of communities to participatein managing their heritage in more particular cases. Theright to culture and the right to “belong to” a culture hasbecome an increasingly important topic in contemporaryacademic debates, and this concept has found expressionin international human rights instruments, including the2001 Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Nationalgovernments may not uniformly or enthusiastically endorsethese international rights documents, even when theysign them. Nonetheless, practitioners, scholars, rightsadvocates and community leaders reference them anddraw on rights norms in their own work.In 2009, researchers at the Princess Maha ChakriSirindhorn Anthropology Centre (SAC) proposed toundertake a project on Culture and Rights in Thailand(CRT) with the goal of understanding how these issueswere being negotiated in the context of Thailand. Theconcept of cultural rights and the right to culture isrelatively new in Thailand, and the CRT sought to identifyif there were local, vernacular equivalents to the Western,international discourse of cultural rights. Thailand’s

In the conceptual framing of the project, we alsosought to explore rights as culture and the culture ofrights in Thailand. While Thailand participates actively inthe international rights regime and has a rich discursiveand political history of contesting civil and political rights,thinking through, let alone claiming, cultural rights isa challenge given how effectively state-initiated, topdownpolicies on ‘culture’ have been enacted. Thailandis rich in ethnic diversity, culture and tradition but thisdiversity has been harnessed to a fictive but nonethelesspowerful unitary culturalideal called ‘Thainess’.Difference inThailand, then, canbe encompassed intonarratives of belongingwhich foreclose thepossibilities of overtcontestation or rightsclaiming.“ The Culture and Rights project was designed asa critical academic research project, the findingsfrom which could further the SAC’s mandate ofcontributing to policy-making and to giving voice tocommunity perspectives on cultural heritage.”We were aware from the start how the ‘problemof culture’ has inserted itself into public discussions ofhuman rights, particularly in the 1990s when human rightsframeworks were sometimes rejected by governmentsin the name of resisting the West and “preservingculture’. Though Thailand’s social movement leaders andintellectuals were open to human rights (albeit with livelydiscussion about contextualizing global rights norms tomake for more fruitful integration with existing Thai normsabout justice and obligations of the state), the CRT projectmembers were attuned to how these discourses andpractices have been translated and localized.To examine rights as culture means understandingrights as a discourse, and a fluid and contested bodyof practice. Anthropology has also embraced anunderstanding of culture as practices that are opento change and contestable. But with the expansion ofrights discourse at the international level, scholars notethat there is an increase of “culturalist” claims made bygroups invoking ideas of distinctive language, tradition,locality, race, ethnicity or religion as the basis of theirclaims to land, political autonomy or the repatriation oftraditional cultural resources. In some instances, culturalrights are invoked to justify opposition to projects whichpose a threat to a culturally distinctive way of life, in otherinstances cultural rights are invoked to claim exemptionfrom the laws binding other citizens. The CRT researcherswere keenly aware of these dimensions to cultural rightsclaims and sought to document the ways that groupclaims in Thai contexts, while by no means exempt fromthe potential risks of essentializing, are often strategicallyadopted when negotiating with the state.The Cultureand Rights projectwas designed asa critical academicresearch project,the findings fromwhich could furtherthe SAC’s mandateof contributing topolicy-making and to giving voice to communityperspectives on cultural heritage. The multi-facetedaspect of the project pushed the CRT researchers tofind ways to communicate their findings to differenttypes of audiences. To achieve this objective, the CRTsupported stakeholder engagement projects that enabledresearchers to return to their field-sites and shareinsights from their findings to relevant audiences. Thesestakeholder engagement projects (or action-researchprojects) took the shape of seminars with communityleaders, government officials and representatives from civilsociety in different settings. In some cases, these projectsproduced short films where the views of the communityand government representatives can be heard.7

The Culture and Rights in Thailand project wouldnot have been possible without the administrative andprogram management support from the Centre—thesupport which makes collaborative critical inquiry possible.It is difficult in Thailand to find settings where empiricalsocial science research and scholarly exchange isnurtured and supported, and where the research findingscan be disseminated widely—and in the case of the CRTin both Thai and English. Though the project was broughtto conclusion in September, 2012, our work continueswithin SAC where we are conducting a series called theCultural Rights Forum. http://www.sac.or.th/databases/cultureandrights/resources-2/cultural-rights-forum/Throughout the year, we read and discuss important articles from cultural rights debate and familiarizeourselves with innovations in programming at other cultural institutions that seek to reassess how the interests ofsource communities can best be reflected as these institutions forge their policies on documenting, archiving anddisseminating knowledge about cultural heritage. Cultural rights can get activated in the space where the institutionsmeet the communities whose heritage they are representing. Institutions such as the SAC can play an importantrole in mediating interests of government agencies, community leaders, researchers and other practitioners. It is ourhope that the knowledge gained through the CRT project can be of help as SAC defines its role in the on-goingdebates about cultural rights.This article is dedicated to the memory of Arithat Srisuwannakij (Tieng). Until hisuntimely death in December, 2012 Tieng was a vital presence in the CRT and inthe Cultural Rights Forum.

Voices from the Field:Documenting Kantreumand Language Rights in Surin Provinceby Majid BagheriMr. Majid Bagheri is an Iranian filmmaker and video artist who is interested in performance art, installation art,documentary, and narrative cinema. In 2011, he finished his Master’s degree at the School of Interactive Artsand Technology at Simon Fraser University and subsequently spent six months in Thailand supporting filmproduction at the SAC (December 2011-May 2012).“Without the revitalization of Khmerlanguage skills among the youngergenerations of ethnic Khmer, therewas little chance that this genrewould exist in the near future.”In December2011, I arrived inBangkok to begin mywork with the SirindhornAnthropology Centre.In addition to providingtechnical support to theaudiovisual team at SAC,one of my main tasks was to assist with the production of afilm documenting the local perspectives and preservationefforts of Northern Khmer musical forms, particularly amusical genre called kantreum.The film project was part of the Culture and Rightsin Thailand project at SAC, and was managed by Dr.Peter Vail, an anthropologist from the National Universityof Singapore, and Mr. Chaimongkol Chalermsukjitsri, alocal researcher and coordinator. Since 2009, Dr. Vail andMr. Chaimongkol had undertaken collaborative research inSurin province to understand the vital links between ethnicKhmer language and the transmission and preservationof the musical genre of kantreum. I was there to supportthem in the production of a film about the loss of theKhmer language and its impact on traditional musicalexpressions.Even though I had read numerous articles andtheses about the ethnic Khmer in Thailand’s northeasternprovinces, when I arrived in Surin, I realized that Iknew next to nothing about the ethnic Khmer and theirculture. For example, I had expected to find more overtand visible expressions ofKhmer ethnic identity, butinstead I encountered ageneral indifference andsome opposition towardsany such identifications.From talking with Dr. Vailand Mr. Chaimongkol, Icame to understand that this widespread reluctance toidentify openly as ethnically “Khmer” was partly due to thegeneral regard of the central Thai language as the routeto prosperity, and partly a result of the stigma associatedwith Khmerness given the history of Khmer Rouge inCambodia. I had also underestimated the impact of theglobal cultural industry on rural areas, and was surprisedat how the cultural preferences of the youth were shapedby these global influences, marginalizing the traditionalcultural expressions to the point of extinction.Mr.Chaimongkol teaching English andKhmer at a local monastery

An ethnic Khmer native of Surin province andlanguage rights activist, Mr. Chaimongkol has travelledextensively around Thailand, and even across theborder to Cambodia in his efforts to safeguard the localKhmer heritage and language. In addition to bringingtogether the old masters to play traditional music,Chaimongkol was also involved in the digitization ofKhmer Buddhist scriptures and the organization ofKhmer language lessons at local monasteries for bothadults and children. He had turned his home on theoutskirts of Surin into a centre for the preservationand propagation of the local Khmer culture. He haddevoted his own time and resources to these activitiesand it was impossible to be in his proximity withoutfeeling the same commitment, concern and affectionfor the local heritage. Dr. Vail had also done a greatdeal of research in the area and knew many of thelocal musicians and culture bearers. He spoke fluentThai and some Khmer, which proved extremely helpfulduring the production and editing of the film. Hisinsights, natural curiosity and great rapport with thelocal people complemented Chaimongkol’s devotionand connectedness to the local community. Togetherwe devised a tentative spine for the documentary thatdetermined how it would unfold.10Local masters playing together at Ta Lon’s houseThe film, entitled “Grabbing the Blue Tiger:The Past and Future of Northern Musical Khmer Arts,”explores the challenges in safeguarding the local Khmerlanguage and heritage using kantreum as a point ofentry. Through interviews with several generations ofkantreum performers and local heritage advocates andexperts, the film documents the myriad social, economicand cultural forces which have led to the gradual declineof the traditional form of kantreum, known as kantreumdangdeum. Once performed primarily for healing andspirit mediumship rites called col maemot, kantreumdangdeum was now increasingly being performed only forcultural heritage events, while the more popular, electronicgenre, called kantreum prayuk, could be found widely onlocal stages and in CD stores in Surin, and as far afieldas Cambodia.Another core message of the film had to do withthe centrality of Khmer language to the transmission ofkantreum dangdeum. Without the revitalization of Khmerlanguage skills among the younger generations of ethnicKhmer, there was little chance that this genre would existin the near future.Ta Lon singing kantreum at a Maemot(spirit mediumship) ceremonyReflecting on the collaborative filmmakingprocess, for me, the language was the greatest barrier,and both Peter and Chaimongkol tried their hardest to fillme in whenever possible. During interviews, sometimesI generally understood what was being said, but othertimes I was totally in the dark. We would film part of aninterview, pause to have a brief discussion, and thendetermine how to proceed, deciding how to adapt ouroriginal plan. By the time the film was finally edited, I knewmost of the interviews almost word-by-word. Anotherchallenge of the filmmaking process was that our planswere frequently disrupted by the spontaneous changesthat were made in the filming schedule. Even so, I feltvery respected and included in all aspects of the projectand I am greatly thankful for that.One of the oft-cited risks of filmmaking in anunfamiliar culture is the tendency to exotify the “Other.”This risk becomes greater with visual media, whichcan be very powerful and convincing. The filmmaker’s

gaze is constantlyupon the characters,determining what is tobe recorded and howit should be focalized.As such, there is thetendency for a filmmakerto present one worldviewor narrative over all thepossible others, and itis only through a criticalawareness of such“Indeed, one of the core challengesof this kind of collaborativedocumentary production is tobalance the ethics of respecting theprivacy and personal boundariesof the individual characters withthe aims of reaching a wideraudience with a compelling film.”power relations that one can present a more sensitive,nonjudgmental account of the context. Throughout theproduction, we tried to maintain an acute awarenessof this issue in order to transcend the surfaces andreach the underlying human connection. Because of thecollaborative engagement with local culture bearers suchas Chaimongkol, I believe we were quite successful atavoiding any exotic or orientalist representations of theethnic Northern Khmer.Mr.Chaimongkol children playing at Ta Lon’s houseWhen it came to appearing on camera, the peopleof Surin were surprisingly relaxed and well-spoken, as longas we avoided certain sensitive issues that were viewedas potentially detrimental to their social or vocationalpositions. Some of the interviewees spoke their mindswhen the camera was not around, but refused to do soon record. On issues regarding state policies towardsmother tongue language acquisition in school, mostpreferred to voice their official positions rather than theirpersonal opinion. This was a significant challenge for ourproject. A documentary film succeeds when it representsthe reality of a given situation in all its complexity, whichoften means includingopposing perspectives.However, since someof the participants didnot feel comfortablespeaking openly, theirvoices were not fullyrepresented, making itdifficult to portray thesituation. Indeed, one ofthe core challenges ofthis kind of collaborativedocumentary production is to balance the ethics ofrespecting the privacy and personal boundaries of theindividual characters with the aims of reaching a wideraudience with a compelling film.Unlike a fictional film, the narrative structure ofa documentary is not prewritten, but rather discoveredduring and after production—carved out on the editingtable from the recorded footage. Although the filmmakersmust sketch a preliminary plan, it only acts as a generalguideline, and is constantly modified to accommodatethe changing situation. In terms of structure, mostdocumentary films do not have an ending in its classicalnarrative sense. There is no clear resolution, and, indeed,that is the power of documentary; to raise a question ratherthan giving an answer. The narrative of a documentaryis more or less post-modern, related through variousvoices, which sometimes can be incompatible, unreliableor incomplete. It is left to the viewers to draw their ownconclusions and interpretations of the story.Finally, time is an essential necessity for adocumentary project, since different pieces are foundrather than recreated. The filmmaker needs to be at theright place at the right time to be able to witness whatis deemed relevant to the story. Since these meaningfulmoments often occur unexpectedly, a great deal of timemust be spent in the field with the characters in order tobuild rapport and glean the valuable moments as theyoccur. A lot of time is also needed for editing, since againthe story needs to be found and shaped from what isrecorded. An organic story is lying there in the film rushesto be found and thus brought to life.11

Focus on Research:Exploring Cultural Heritage Rightsat the Prasat Hin Phanom Rung Historical Parkby Alexandra DenesDr. Alexandra Denes is a Senior Research Associate at the Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre and the ProjectDirector of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and Museums Field School, Visual Anthropology Program, and theCulture and Rights in Thailand Project at the SAC.The Prasat HinPhnom Rung sanctuary isan ancient Hindu templelocated in Buriram Province.Constructed of sandstoneand laterite between the10th and 12th centuries C.E.and dramatically situated atop an extinct volcano, thetemple originally functioned as a symbol of the Hinducosmos and as a ritual space for the legitimation ofAngkorian era rulers, known as devaraja, or god-kings(Chandler 2000). With the collapse of Angkor in the 15thcentury C.E., the Phnom Rung sanctuary and similarAngkorian era, Hindu religious structures in the regionlost their original symbolic and ritual functions, and yetthey were not completely abandoned. Rather, subsequentsettler populations of ethnic Khmer, Lao, Kui and ThaiKhorat inscribed the sanctuaries with their own mythsand incorporated them into their animist and Buddhistbeliefs and practices.“Many of our local informants toldus that they felt that their values andcultural practices of pilgrimage had beenmarginalized and forgotten in this process ofconstructing Phanom Rung as a major touristdestination and site of national heritage.”Between October 2010and June of 2012, a teamcomprised of myself,Tiamsoon Sirisrisak (MahidolUniversity), RungsimaKullapat (VongchavalitkulUniversity), and staff from theSAC undertook field research with nine communities inthe vicinity of the Prasat Hin Phnom Rung Historical Parkin Buriram province, in order to better understand localresidents’ relationships to the ancient sanctuary and otherarchaeological sites in the park, and to learn more abouthow the sanctuary’s incorporation into Thailand’s nationalheritage had impacted this relationship.From our interviews with local residents of NongBua Lai village, Khok Muang village, Bua village, and TaPek village, among others, we found that Phnom Rungsanctuary and related ancient structures in the vicinityhad long been regarded as sacred abodes of protectivetutelary spirits (chao thi). Every year in April, on the waxing

moon, local villagers would travel by foot and by oxcart tomake a pilgrimage to Phnom Rung, to pay respects to thetutelary spirits of place with incense and offerings, offeralms to the forest monks living in the vicinity, and worshipat the Buddha’s footprint (phraphutabat) which had beenplaced within one of the sanctuary towers. While thereis no archival evidence indicating exactly when theselocal beliefs and pilgrimages began, the French surveyor,Etienne Aymonier, who visited the site in the late 1800sand observed the pilgrimage, suggested that they werepracticed for at least one hundred years (Aymonier 1901).Our informants explained that their ritual relationship toPhnom Rung changed dramatically with the restorationof the sanctuary and opening of the Historical Park in1988. In order to complete the restoration, the Buddhistmonastery, Buddha’s footprint and resident forest monksthat were located near the sanctuary at the summitwere moved down to a plot of land near the base of theancient stairway. This separation of Buddhist and Hindureligious space was more than just an aesthetic choiceof conservationists—it also represented the erasure ofthe syncretic, local, living meanings of the site in orderto inscribe a scientific, archaeological narrative of thesanctuary as part of the nation’s official heritage.The impact of this process of incorporation intonational heritage could also be seen in the transformationof the local, annual pilgrimage into a state-sponsoredcultural spectacle for tourists, featuring reinvented ancientHindu-Brahmin rituals and the staging of a sound andlight performance. Many of our local informants told usthat they felt that their values and cultural practices ofpilgrimage had been marginalized and forgotten in thisprocess of constructing Phnom Rung as a major touristdestination and site of national heritage.Building on these findings from fieldwork, inFebruary 2012, a team from the SAC organized a twodaystakeholder forum entitled “Community Participationin Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage,” withrepresentatives from nine communities in the vicinity of theHistorical Park. The aim of this forum was to invite localresidents to share their beliefs, stories and memories aboutthe archaeological sites within Phnom Rung Park, and todocument these intangible values using a participatorycultural mapping process. Furthermore, in keeping withtwo decades of international legislation in the heritagesector recognizing the intangible values associated withheritage sites and the rights of communities to access andinterpret their cultural heritage, a corollary objective wasto generate recommendations for supporting communityparticipation in the management, use and interpretationof the sanctuaries.In the cultural mapping process, participantsidentified historical paths of pilgrimage to Phnom Rungsanctuary prior to the road construction, and marked thelocations of spirit houses and other mythic and sacredsites within the local landscape. In contrast to standardmaps of the Historical Park which focus predominantlyon the archaeological sites from a either a conservationmanagement or tourism promotion perspective, theresulting cultural map of Phnom Rung offered a compellingvisual affirmation of the longstanding spiritual significanceof the sites to local populations of ethnic Khmer, Lao andThai Khorat, thus rendering these living, intangible aspectsvisible and tangible.In addition to the maps, the stakeholder forumalso generated a substantial list of recommendations fromparticipants about how to support the safeguarding ofthese intangible values. One of these recommendations

“Returning to the question at hand, can these local, intangible values inscribed in the sites existalongside these dominant narratives, or do these “authorized heritage discourses” (Smith 2006) firsthave to be deconstructed in order to create the space for alternative interpretations of heritage?”was to establish a local committee comprised ofcommunity leaders who would have a formally recognizedrole in decision-making about the management andinterpretation of the sites within the park. One headwomanfrom Ta Pek village, Ms. Pan Thitkratok, suggested thatsuch a local committee should have a role in planningthe annual Phnom Rung festival held each April togetherwith other key government offices and facilitating accessto the sanctuaries for locally organized cultural eventsand rituals. Another recommendation was to integratethe cultural maps into the local school curriculum as atool for teaching about the intangible values associatedwith the sanctuaries, thus fostering greater respect andunderstanding among younger generations.All in all, the field research and mapping processin the vicinity of the Phnom Rung Historical Park revealedthat the communities living near the archaeological siteshad inscribed these edifices with their own spiritualand mythical meanings, incorporating them into a livingcorpus of animist and Buddhist beliefs and practices.Indeed, this practice of reinterpreting and reincorporatingarchaeological sites into animist and Theravada Buddhistbelief systems has been widely observed by scholarsof Southeast Asia such as Srisaksa Vallibothama, whodescribed this widespread practice as a kind of revival andtransformation of “dead” religious architecture (Srisaksa1995).However, what this research also revealed isthe challenge of creating a space for recognition ofthese intangible meanings and living values in a nationalcontext where the field of heritage conservation is stillby-and-large focused on the preservation of the physicalfabric of the sites according to rationalist, scientific,and archaeological principles, and where access andmanagement of heritage sites is influenced by the touristindustry and by politicians. Returning to the question athand, can these local, intangible values inscribed in thesites exist alongside these dominant narratives, or dothese “authorized heritage discourses” (Smith 2006) firsthave to be deconstructed in order to create the space foralternative interpretations of heritage? The larger challengethat lies ahead is how to raise critical awareness amongthe different stakeholder groups in Thailand about theinherently multivalent and contested nature of heritage,and the rights of communities to have a say in how theirheritage is managed.References CitedAymonier, Etienne. [1901] 1999. Khmer Heritage in Thailand. Translatedby Walter E.J. Tips. Bangkok: White Lotus Press.Chandler, David. 2000. A History of Cambodia. Third edition. Boulder:Westview Press.Smith, Laurajane. 2006. The Uses of Heritage. New York: Routledge.Srisaksa Vallibhotama. 1995. “Sri Sa Ket: Sisaket khet khamen padong”[Srisaket: The Area of the ‘Backward Cambodians’]. In Khon ha aditkhong mueang boran, edited by Namphueng Ratana-ari, 373-401.Bangkok: Muang Boran.More detailed data and analysis about this researchproject can be found in a chapter in the forthcomingedited volume, Rights to Culture? Language, Heritageand Community in Thailand (Silkworm Press, 2013), andin an article in the centenary volume of the Journal of theSiam Society, entitled Protecting Siam’s Heritage (2013).A short film about the stakeholder forum and culturalmapping process in Buriram Province is available at theCulture and Rights in Thailand website: http://www.sac.or.th/databases/cultureandrights/

The State and Ethnic Identity of the Phu Tai:A Case Study from Mukdahanby Sirijit SunantaDr. Sirijit Sunanta teaches in the Cultural Studies and Multicultural Studies Programs at the Research Institutefor Languages and Cultures of Asia, Mahidol University. She joined the Culture and Rights project in 2010 aftercompleting her doctoral degree in Women’s and Gender Studies from the University of British Columbia, Canada.When I started writing my proposal for the Cultureand Rights project in 2009, I had read a range of literatureon multiculturalism and cultural rights, mostly written byscholars placed in the Western world. Having been awayfrom Thailand for my graduate studies for more than sixyears, upon my return, I was surprised to learn that leadinginstitutions and scholars in Thailand were discussingcultural diversity, multiculturalism, and cultural rights, topicsI did not hear much of ten years earlier. Highland groupswho had formerly been known as chao khao (mountainpeoples) and chon klum noi (ethnic minority) had nowbegun organizing as indigenous peoples. The sense ofpolitical correctness and cultural sensitivity had begunto develop to the extent that groups such as chao khaowere now referred to as klum chatiphan (ethnic groups)rather than chon klumnoi, a pejorative term that signifiesnon-Thai groups who pose threat to the state. Thai stateagencies, following internationalorganizations and nongovernmentalorganizations,had started to make use of thevocabulary of cultural diversity,local wisdom, and communitybaseddevelopment (Connors2005), and the state had begunto allocate significant resourcesfor revitalizing local and ethnic cultures, supporting locallivelihoods, and regenerating local histories. I decidedI wanted to take part in the discussions and try tounderstand the shift towards a more inclusive notion ofThai national identity and a new emphasis on pluralizedand localized “Thai-ness.”Ban Phu: A Phu Tai VillageRecommended by a colleague, I chose Ban Phu,a village in Nong Sung District, Mukdahan Province, tostudy local understandings and implications of culturalrights in the Thai context. Consisting of 250 households, thevillagers of Ban Phu are mostly related to each other andare of the Phu Tai ethnic group, one of the major ethnicgroups in northeast Thailand. Ban Phu is known as anoutstanding model for community development projectsand has won a number of titles in this regard. Morerecently, the village has also been chosen as a sitefor community culture projects. In 2009, the Bank forAgriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives nominatedBan Phu as a Model Sufficiency Economy VillageLevel 3; the village received a cash award fromMukdahan’s Wattanatham Thai Sai Yai ChumchonProject the same year.The Phu Tai,who speak a Tai languagethat differs from the Thai-Lao language spokenby the majority of thepopulation in the northeastand from Central Thai,the national language ofThailand, are recognizedas a klum chatiphan, or an ethnic group, in Thailand.Entitled to full Thai citizenship rights, the Phu Tai inNortheast Thailand today are descendants of Phu Taimigrants forced to move from the west side of the MekongRiver during the war between Siam and King Anu ofVientiane in the first half of the nineteen19th century. They“I found that decades of staterural development policies andthe prevalent localism discoursehad significantly shaped the waythe Phu Tai in Ban Phu relateto their ethnic identity and theirunderstanding of citizenship today.”

were among tens of thousands of Lao, Phuan, Saek,Kaloeng, and Bru peoples who were relocated in Siam’sattempt to empty towns and cities on the western sideof the Mekong to permanently destroy the Lao Kingdomand cut off supply lines to Vietnam, Siam’s main rival atthe time. Groups of Phu Tai were settled in what are todayMukdahan, Nakhon Phanom, Sakon Nakhon, Kalasin, andUdon Thani provinces. Despite their active political rolein the Free Thai Movement and the Communist Party ofThailand (CPT) during and after World War II (Piyamas2002), the Phu Tai were generally perceived as a “good”and non-threatening ethnic group in post-Cold WarThailand. They have become known in the wider Thaisociety as the Wiang Ping of the Isan region for theirexotic culture and beautiful women. Phu Tai silk textiles,pha prae wa (brocaded silk scarves), produced underQueen Sirikit’s Arts and Crafts Project, are known as “thequeen of silk textiles” and have become a highly prizedcommodity.The Absence of Cultural RightsCultural rights, according to the literature, generallyrefer to special rights for ethnic, religious, and cultural minoritygroups within the state, which support the recognition oftheir cultural practices and the preservation of their culturalheritages and group identities. Historically, the modernThai state has placed great emphasis on integratingpeoples of diverse cultural heritages into the unified Thaicitizenry. National language and education policies havelargely played an assimilating role while the media andthe construction of national historical narratives havecontributed to the homogenization of Thai national identity.I went to Ban Phu with this understanding ofcultural rights in mind, and started exploring how Phu Taivillagers felt about being a member of an ethnic minoritygroup in Thailand, and to see whether the Phu Tai wereasserting any forms of cultural rights claims. I found itdifficult to start a conversation about cultural rights inthe Phu Tai in the village. First of all, the cultural rightsconcept is new in Thailand and it is difficult to explain tothe villagers what it constitutes. Second, when I askedhow they feel about the marginalization of ethnic identitiesby state policies, my Phu Tai respondents were perplexedby the question and found it irrelevant for their own case.“We are proud to be Thai, we are Phu Tai, not chon klumnoi (minorities)” is the reply I often received. My studywas then diverted to formulating an explanation for theabsence of cultural rights consciousness among the PhuTai in Ban Phu and to understanding the relationship thePhu Tai have with their ethnic identity. I found that decadesof state rural development policies and the prevalentlocalism discourse had significantly shaped the way thePhu Tai in Ban Phu relate to their ethnic identity and theirunderstanding of citizenship today.A Development-oriented Village andthe Legacy of the Cold WarDuring my fieldwork, I was struck by thedevelopmentalism narrative that dominated the villagers’self-representation. Villagers often recounted stories fromback in the 1960s and 1970s of how Ban Phu villagersfought to acquire electricity, a high school, and pavedroads. I heard stories about the formation of village youthgroups to promote village development and the concretebenefits that the villagers derived from their connectionswith high ranking military officials and the palace. Themost recited story was that of Ban Phu villagers’ audiencewith the King and Queen of Thailand at Chitlada Palace in1974, facilitated by General Saiyud Kerdphol, the directorof the Communist Suppression Operations Command.During the meeting with the monarch, Ban Phu villagersasked for a high school to be built in their village and itwas granted. In 1975, the military celebrated the openingof the school with a parachute show.During the Cold War in 1950s to 1970s, becauseof its location in the Communist Party of Thailand(CPT)’s area of influence, Ban Phu was subject to Thai

“Ban Phu’s case demonstratesthat the preservation andrevitalization of local culturesoften have developmental ends—tourism, self-sufficiency economy,and local industry and business—that do not directly promote theconsciousness of cultural rights.”Cold War state policies. Ledby the understanding thateconomic development wasthe solution to the nation’ssecurity problems, the ThaiCold War state concentratedon rural developmentprograms, especially insecurity sensitive areasincluding Northeast Thailand.Ban Phu villagers actively joined government-initiateddevelopment projects. They worked closely with theCommunity Development Office in forming occupationalgroups such as weaving groups and handicraft-makinggroups. In the context of state-guided developmentalism,Ban Phu villagers embraced state development policiesas rural citizens and not as members of the Phu Tai ethnicgroup. Ban Phu’s invented lai kaew mukda woven silk, forexample, was promoted as a local product of Mukdahanwithout special mention of the Phu Tai wisdom or identity.It was only when the villagers started their tourism andhomestay project that they began to intentionally performtheir Phu Tai identity for the consumption of visitors fromoutside the community.The Ban Phu Homestay Project was launched in2007 with the support of the Nong Sung District CommunityDevelopment Office. Ban Phu’s visitors are mostly stateofficials and local administrative employees who comein groups for an educational tour to learn about BanPhu’s development and Sufficiency Economy Projects.The villagers welcome their visitors in Phu Tai traditionalclothes and serve a Phu Tai dinner accompanied bycultural performances such as music and dances. Thevillage’s products—hand-sewn Phu Tai-style shirts,sarongs, sin, hand-woven cotton shoulder cloths, andother handicrafts—are displayed for sale during theguest visits. The Ban Phu Homestay Project has provenprofitable; in 2007, Ban Phu’s total homestay income was1,856,660 baht.Culture as Rights or as Resources?Ban Phu’s case demonstrates that the preservationand revitalization of local cultures often have developmentalends—tourism, self-sufficiency economy, and localindustry and business—that do notdirectly promote the consciousnessof cultural rights. The promotionof the local culture industry,including tourism, contributes tothe revival of Phu Tai weaving,dress, and performances, butnot to all aspects of the Phu Taicultural heritage. The local schoolchooses to teach Phu Tai cookingand dance performances rather than Phu Tai languageas part of the local curriculum. Ban Phu villagers havealmost completely lost their ability to read the ancientLao Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts that the previousgenerations left them. Traditional yao healing practiceshave already disappeared from Ban Phu.Phu Tai Cultural Heritage and FutureProspectsA few possible actions can be taken to preserveand revitalize Phu Tai cultural heritage. Network andcoalition-building among the Phu Tai from differentvillages and provinces in Thailand as well as fromacross national borders would be an important step topromote and revitalize Phu Tai ethnic identity. Regionalscholars and cultural activists can play a leading role inbuilding and supporting a cultural rights movement andencourage the organization of ethnic minority groups inNortheast Thailand. The state should take an initiative toform a national policy that promotes the teaching of ethniclanguages in school and facilitate the revitalization ofscripts. These moves would increase chances for minoritycultures such as Phu Tai to survive into the future.ReferencesConnors, Michael Kelly. 2005. “Democracy and the Mainstreaming ofLocalism in Thailand.” In Southeast Asian Responses to Globalization:Restructuring Governance and Deepening Democracy, edited by FrancisLoh Kok Wah and Joakim Öjendal, 259–86. Singapore: NIAS Press.Piyamas Akka-amnuay. 2002. “The Phuthai People and Their PoliticalRoles on the Phu Phan Ranges During 1945–1980.” Master’s thesis,Mahasarakham University.

The Community Forest Movement’s Strategic Useof Culture in Rights Claiming Process:Reflections from field researchby Bencharat SaechuaBencharat Sae Chua is a PhD candidate at La Trobe University, Australia, and a lecturer at the Institute ofHuman Rights and Peace Studies, Mahidol University.Regulations on pu ta forest managementat Kok Somboon village, Sakon Nakorn.“The community’s rights in the management, maintenanceand exploitation of natural resources in a balanced andsustainable fashion as guaranteed by Section 66 of the(2007) Constitution are rights that evolved from longtermsystematic practices associated with communitylivelihoods. The rights which emerged this way are notbasic human rights. They are, therefore, not the rights thatthe Constitution aims to protect. They are merely the rightsthat the Constitution acknowledges, recognizes and wishesto promote to the communities to properly exercise. Thelaw that puts certain conditions and regulations upon thecommunity’s rights in the management, maintenance andexploitation of natural resources is therefore not in violationof human rights1”The above letter from the Prime Minister SurayudJulanont to the Constitutional Court explaining the CommunityForest Bill passed during his term reflects an interpretationof the community rights provision in the 2007 Constitution.After two decades of public debates on whethercommunity settlement should be allowed in protectedforest, the National Legislative Assembly (NLA) passed theCommunity Forest Act in late November 2007. Under Article25 of the Act, the communities that had settled inside theprotected forest before the demarcation of the protectedarea, and had managed the forest as a community forestfor at least ten years before the Act came into effect, couldask for permission to manage the forest communally. Thecommunities settled “outside” the demarcated protectedforest, however, were excluded from such rights althoughthey may have also been taking care of and using the forest.In addition, Article 35 prohibits the cutting and collecting ofwoodlots in the community forest inside the protected areas.This would prohibit the use of forest timber for consumptionor for household needs, such as repairing houses.The letter from the Prime Minister in defense ofthe Community Forest Bill shows how “community rights”are often seen as contingent upon the responsibility of thecommunities to take care of the forest. Interestingly, thestrategic rights claiming process and discourse associatedwith the community forest movement are also based on asimilar argument of responsibility to protect the forest. Thecommunity forest movement asserts that local communitiespossess traditional knowledge of how to live in harmonywith their forest environment, and therefore are legitimatelyentitled to live in and manage the forest. Such environmentaldiscourse powerfully challenges the Thai state’s policies ofcentralized control of Thailand’s forests. However, the extentto which community rights claims are being accepted asfundamental rights of access to forest resources is still beingnegotiated through the interactions between the movement’srepresentatives, the state and the wider public.1 The Prime Minister’s letter (Urgent) No. Nor Ror 0503/1184, dated 16January 2008, cited in the Constitution Court Ruling No 15/2552, dated4 November 2009.

In the research “Rights Claims and the Strategic Useof Culture to Protect Human Rights,” I explore suchinteraction. Looking at the rights discourse from a socialconstructionist standpoint, I do not search for a definitemeaning of community rights. Instead, I attempt tounderstand how rights are perceived and claimed andhow culture is used strategically as a resource in suchprocess.In search of rights: Rights claimsbased on legitimacyDuring my field research in two northeasternvillages that participated in the community forestmovement, I set out to identify and better understand thetraditional forest-related practices such as those that wereoften cited by the movement’s supporters as the basisof community rights and legitimacy to live in protectedareas. However, I soon learned that this task was not assimple as I initially expected it to be.One of the most prominent strategic framing processesused by leaders of the community forest movementin Thailand was the reference to communal traditionalknowledge and cultural beliefs and practices which reflecta harmonious, respectful and sustainable relationshipwith the forest. In this strategic discourse, local culturalpractices are reinterpreted within an environmentalistframework to support the villager’s claim for legitimacy.For example, the beliefs and practices surrounding thesacred shrines of the ancestral spirits (pu ta) 2 are oftenexplained in environmental terms, as traditional beliefsthat promote environmental conservation. Some “localtraditional practices” are also formalized and labeled withenvironmental values. The significant case in point is theformalization of communal land/forest use by demarcatingcertain areas as “community forests” (pa chumchon). Thepa chumchon is to be managed according to communityforest management regulations and monitored by acommunity committee.From my discussions with local residents,however, I learned that most villagers were not explicitlyconscious of the environmental implications of the pu ta2 Literally, pu ta means grandfather.A pu ta shrineforest and pa chumchon, with perhaps the exception ofa few community leaders. In the two villages I studied,the villagers rarely used the pa chumchon, and mainlycollected forest products from the protected forestsurrounding the villages. To my surprise, many were notaware of the existence of the pa chumchon in the villageat all. Having witnessed the community forest movement’sstrategic use of culture to assert claims of resourceentitlement on behalf of the community, I became morecritically aware of the need to examine the communityrights discourse from a constructionist perspective.Both of villages where I conducted field researchdiffered markedly from the prevailing image of the “localtraditional community” as represented in Section 46 andSection 66 of the 1997 and 2007 Constitutions respectively.Firstly, the villages were relatively new, having beenestablished by economic migrants in search of agriculturalland during the 1950s and 1960s. Moreover, one of thevillages was linguistically and ethnically diverse, andtherefore that village did not have a shared body oftraditions or homogeneous cultural practices to constitutea unified, collective identity. In both villages, the so-called“cultural practices” related to forest conservation werenewly introduced, mainly to support the struggle to remainliving in the protected forest.

The community forest movement often refers tolocal communities as forest people who are engaged in asubsistence economy. In the communities that I studied,however, villagers were generally more dependent on themarket than on the forest. While forest products providedfood supplies and extra income to the villagers of bothcommunities, the villagers were mainly dependent on cashcrops or on remittances from family members working inthe city to meet their other basic needs. In stark contrastto the prevailing image presented by the communityforest movement, their lifestyles were not those of thesubsistence livelihood forest dwellers, and farmland, notforest products, was the crucial resource for the villagers’survival.However, the community forest movement avoidsthe discussion of land rights for fear of their perceivedassociation with forest encroachment. As a result, theconstructed community rights discourse is mainly aboutthe rights to natural resources management, not aboutthe essential needs of the movement members: accessto forestland for viable commercial agriculture. This isevident from various drafts of the Community Forest Billproposed by the community forest movement in the pasttwo decades. While the debates on the Bill are mainlyabout whether communities should be allowed to manageprotected forest, every draft of the Community ForestBill prohibits land occupation, settlement, and farmingwithin the community forest. Literally speaking, therefore,even if the communities’ rights to manage communityforests were legally recognized, their residences andtheir farmland within the protected forest would still beat risk of eviction. The community forest activists hope,nevertheless, that if the communities were allowed a rolein forestry conservation, it would automatically follow thatthey would be allowed to stay in the forest.Rights in ContentionOn 29 September 2008, the National Human RightsCommission (NHRC) requested the Constitutional Court torule on the constitutionality of Article 6, the National ParkAct 1961 (B.E. 2504), which allows the government to decideto “reserve any land with interesting natural conditionsin order to maintain its condition for the educational andleisure purposes of the people” and demarcate that area0as protected forest. The demarcation of a protected areaentails the exclusion of human settlement from the area,including in the cases where local communities had settledthere before the area became protected forest. The NHRCargued that such a provision violated Section 66 and 67of the 2007 Constitution, which guarantees communityrights to natural resources management. The ConstitutionCourt ruled that the Article 6 of the National Park Act didnot affect human rights and is not unconstitutional. TheCourt backed the spirit of the Act to “protect the existingnatural resources … not to be destroyed or altered. Themain objectives are to protect and maintain public interestand the interest of the people in general 3 ”.The Constitutional Court’s decision reiteratesthe fact that a community’s rights to natural resourcesmanagement or, in fact, the rights to access naturalresources as a means of livelihood, are often placed inan inferior position to the national and public interests inpublic policy making. It also raises critical questions aboutthe community forest movement’s strategy of continuingto promote the idiom of “traditional culture” in compliancewith the national interest to protect the forest.The community rights discourse of the communityforest movement has been evolving and changingover the past two decades, and has made its wayinto Constitutional provisions and into the wider publicdiscourse. Nevertheless, the meaning and scope ofcommunity rights is still being negotiated, and the rightsneed to be better respected and protected. Approximately1.2 million people with de facto rights to live in protectedforest are still at risk of being evicted as long as their rightsto land and basic livelihoods are deemed as incompatiblewith the larger “public good” of forest conservation.Rather than focusing on representing communities as theliving embodiments of “traditional culture,” the questionthe movement needs to ask is as follows: how can acommunity’s right to livelihood and natural resourcesbe effectively balanced with the state’s goals for forestconservation?3 P. 4 The Royal Gazette, Vol. 129, Section 40 (Kor), dated 10 May 2012.

Regional Anthro News:The Mukurtu Workshop at the SACby Alexandra DalferroAlexandra Dalferro is an English language content developer at the SAC. She received her BA in East AsianStudies and Anthropology from Columbia University, and she was a Fulbright Junior Researcher from 2009-2010, working on an ethnography of the legal lottery system in Thailand and the roles of itinerant ticket sellersfrom Loei province.Before 2008, the above photograph could only be accessed through theManuscripts, Archives and Special Collections unit in Washington State University’sHolland and Terrell Library. Interested parties could read the title, “Three YakamaWomen,” and the description, “A photo of 3 Yakama women in regalia (1911).” Nofurther context was provided, and many critical questions were left unanswered,such as: Who are the three women in the photo? Is their “regalia” also their everydayclothing, or have they dressed this way for a certain ceremony or festival? Does theimage contain any sacred or culturally sensitive aspects that should not be seen bythe general public? Most importantly, who has the right to describe and propagatethe photograph?1

Today, the photograph “Three Yakama Women” is a partof the Plateau Peoples’ Web Portal, an interactive, onlinedigital archive developed by Washington State Universityin 2008 to provide access to Plateau peoples’ culturalmaterials through collaboration with tribal communities.Members of five tribal nations have the ability to addand curate materials from their own tribes, therebyclaiming space for the voices of source communities andchallenging the widespread valorization of institutionalnarratives of objects and histories. “Three Yakama Women”is now presented in rich detail, enhanced with accountsof tribal knowledgefrom Yakama peoplewho are members ofthe web portal.The PlateauPeoples’ Web Portalwould not exist withoutthe free, open-sourcecommunity archive2“The workshop was part of the SAC’songoing Culture and Rights Forum,with interest in Mukurtu arising asresearchers continue to considerthe roles that source communitiesplay in database development anddissemination.”platform Mukurtu, which enables indigenous communitiesto access and circulate digital cultural heritage materials inways that reflect their own cultural priorities. Recognizingthe potential applicability of Mukurtu to its digital databaseprojects, the Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn AnthropologyCenter organized a Mukurtu workshop from the 17th to the18th of December 2012, and SAC staff had the opportunityto learn from and exchange with Dr. Kimberly Christen,Mukurtu Project Director, and Dr. Michael Ashley, MukurtuDevelopment Director. The workshop was part of the SAC’songoing Culture and Rights Forum, with interest in Mukurtuarising as researchers continue to consider the roles thatsource communities play in database development anddissemination.Digital technologies have become so embeddedin daily life that many individuals accustomed to thisseamless integration fail to question the hierarchy ofaccess that determines who can produce and engage withdevices, programs, and content. The Mukurtu programevolved from an effort to address and destabilize thesecategories that shape our understanding of and interactionwith digital platforms such as the internet. In 1995, whenmembers of a Warumungu community in Tennant Creek,Australia started building their own arts and culture center,they achieved the return of many local artifacts that hadbeen housed at national museums across Australia. Inaddition to these physical returns, the community alsoreceived over 700 digitized photographs that were takenby an early missionary to Tennant Creek. Most communitymembers had never seen the images, but upon assessingthe collection, they decided that many photos andthe knowledge surrounding them should not be madeuniversally accessible. Some images contained sacred orsensitive content that necessitated restricted viewership,with only certain kin,gender, or age groupsbeing permitted to seethe images and modifyor contribute relatedcontent.How could thisdigitized collection ofimages be featured atthe arts and culture center without sacrificing the “offline”cultural protocols that influence diffusion of knowledgeand reaffirm positionality and social order within thecommunity? Working alongside Warumungu communitymembers, Dr. Kim Christen began incorporating thesealready-existing community roles and relationshipsinto the digital platform that would become Mukurtu.Each photograph was classified with different levels ofcultural protocols to determine appropriate audience,such as, “restricted community: male AND bird clan.”Every community member has their own username andpassword, and their access level corresponds with theiruser profile, which is determined collectively and set bya system administrator. If a database user’s profile saysthat she is a female member of the snake clan, then thisperson will be able to see and contribute to all “open”content, as well as to all content that is restricted tofemales OR snake clan members, and finally, to all contentthat is restricted to females AND members of the snakeclan. In the Warumungu language, Mukurtu means “dillybag,” or a bag used to hold sacred items. The dilly bagis accessible to members who act responsibly withinthe community and gain the trust and permission ofknowledgeable community leaders. Like the dilly bag,

a Mukurtu-powered archive is a “safe keeping place,” acommunity repository for cultural materials and knowledgethat grows from sustained use, dialogue and negotiations(Mukurtu 2012).Over the course of the two-day workshop at theSAC, Dr. Christen and Dr. Ashley introduced Mukurtu’smain features and instructed SAC staff on how totechnically implement the platform. Although staff are stilldeciding if Mukurtu will beincorporated into any existingSAC databases, the Mukurtuworkshop was a catalystfor needed discussion andexchange. SAC researchersgave presentations ontheir respective projects,specifically highlightingproject target groups and processes of communityparticipation in management and utilization of data. Thepresentations provided valuable opportunities for staffto reflect upon the trajectories of their projects in thecontext of the SAC’s strategic objectives and the sourcecommunity-drivenethos of Mukurtu. In consideringthe SAC’s digital databases, Dr. Paritta ChalermpowKoanantakool, the former director of the SAC, calledfor increased “database dialogue,” or the fostering ofconnections and collaborations across databases andprojects. Before such dialogue can occur, however,target groups must be firmly delineated, which involvesconfronting the perceived dichotomy between academicsand source communities as target user groups. TheLocal Museums in Thailand team is currently grapplingwith this issue as they develop access options for theLocal Museums Database to enable museum staff andlocal community members to contribute and modifycontent. Similarly, the Anthropological Archives Databaseresearchers are creating a system of cultural protocols thatwill protect culturally sensitive content and allow sourcecommunity members to add their own narratives to thematerials gathered by anthropologists.“The availability of Mukurturepresents a crucial steptowards integrating therights and voices of sourcecommunities into all aspectsof heritage management”One concern that was raised by SAC staff, however, isthe suitability of digital platforms like Mukurtu in a localThai context. In communities where computer use is stillvery much determined by age and income, embodyingthe inequalities of the “digital divide,” staff fear thatthe introduction of Mukurtu could unintentionally resultin the creation of an exclusive community-within-acommunityof contributors, or individuals who already havecomputer skills and can attest to the relevance of digitaltechnologies to their daily lives.This inadvertent preferencingof voices would be difficultto avoid in communities withfew computers or computersavvymembers. Moreover,SAC staff worry that in suchcommunities, the desire toutilize a program like Mukurtuwould not emerge from within the community itself,but would instead be encouraged and imposed byresearchers, therefore undermining the researchers’and Mukurtu’s core goal of community ownership andempowerment.The Mukurtu Workshop helped to draw outand illuminate the challenges that face project staff indeveloping dynamic, inclusive, and sustainable digitaldatabases. As cultural heritage resources are increasinglydigitized and made accessible via the internet, practitionerseverywhere must consider how these rich accounts oftangible and intangible culture can be shared in ways thatrespect the rights and priorities of source communitiesand position community members as primary decisionmakers.References CitedMukurtu. “Manual: FAQ.” Last modified May 23, 2012. http://www.mukurtu.org/wiki/Manual:FAQ.The availability of Mukurtu represents a crucialstep towards integrating the rights and voices of sourcecommunities into all aspects of heritage management.3

SAC News:Introducing the Culture and RightsForum at the SACby Alexandra DalferroIn the month of October at the Princess MahaChakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, researchers andproject staff have traveled across Thailand, delved deep intoarchives, and designed and updated databases. Dr. TrongjaiHutangkura, leader of the SAC’s Publicity and NetworkingDivision, has been teaching himself to read and write theancient Thai alphabet of the Sukothai period so that hecan better understand the manuscripts he researches. TheBarefoot Anthropology team spent a week in Mae Hong Sonlending support to Karen villagers as they developed culturalsafeguarding activities. Dr. Narupon Duangwises hosted aseminar on sexuality called “Handsome Gay Kings: When GayMen Long for Masculinity.” These are only a few examplesof the diverse events and processes that occur at the SACon a monthly basis, and they illustrate the organization’s vastscope of interest and engagement. What, then, do theseprojects have in common? How can they be related to oneanother in ways that illuminate shared themes and challengeand enrich objectives and methods? The recently launchedCulture and Rights Forum attempts to address these questionswhile introducing core concepts of cultural rights to SAC staff.The forum will also emphasize how research, documentation,archiving, and communicating on cultural issues need to takeinto consideration the rights of source communities.The Culture and Rights project commenced in 2009as a multi-sited, field-based research initiative for Thai andinternational scholars. As the research progressed, ProjectDirector Dr. Alexandra Denes and Project Advisor Dr. CoeliBarry realized that the ideas and discourse surrounding cultureand rights resonated implicitly with the work of the SAC, andthey wished to draw out and interrogate these embeddedconcepts along with SAC staff. They envisioned a structurethat would allow sustained commitment to the discussion ofculture and rights at the SAC, thereby creating a space forcontinual reflection and institutional identity building. Aftermuch careful planning, the Culture and Rights Forum wasborn. For the next ten months, through June 2013, SAC staffwill meet at least once a month for half-day sessions to4discuss issues ranging from sexuality rights to communityinvolvement in and access to digital heritage. Forum FacilitatorJan Boontinand, a PhD candidate at the Institute for HumanRights and Peace Studies of Mahidol University with manyyears of experience working with Thai NGOs, will guide eachsession, helping to stimulate dialogue that links material frompresenters back to the work of the SAC. Dr. Barry affirms thatthe forum can also be referred to as a “laboratory,” as shewishes to highlight the unique, experimental nature of thisprogram. It is Dr. Barry’s hope that the opportunities the forumwill provide for reflexivity, communication, and connection willstrengthen the SAC’s thematic framework and enable staffto solidify around a more collective identity.The first Culture and Rights meeting was held onSeptember 26th. Participants began by sharing aspects oftheir work that make them feel passionate as well as theirexpectations for the forum. Dr. Barry then gave a generaloverview of the concept of cultural rights and presented herthoughts on Michael Brown’s introduction to his book, WhoOwns Native Culture? Brown explores the operationalizationof cultural rights theories by indigenous groups who haveused this rhetoric to call for repatriation of sacred objectsand control over cultural meanings and replication. Fearingthat the procedures and strategies surrounding these claims,not to mention the cultural forms in question, will becomeincreasingly standardized and codified via intellectual propertylaws, Brown decries practices of litigation and legislation thatturn culture into property and instead advocates approachesthat establish the inherently relational, context-dependentnature of the ownership problem. In his reaction to the forumso far, Chewasit Boonyakiet, a research assistant at the SAC,echoes Brown’s concern, “In Thailand, we don’t really usethe vocabulary of rights yet – we refer to it as heritage that

elongs to certain groups. When claims are made, there isnot a process in place for responding to them. We need tocome up with a multifaceted method - one that does not onlyemphasize community rights, or mainstream museologicalprinciples, for example - but is nuanced and case-specific.”SAC staff wrestled with the ideas of Brown asthey divided into small groups to brainstorm examples ofcultural rights-claiming behaviors in Thailand. Discussionsof the Assembly of thePoor protest of 1997,Yong language andidentity revitalizationin Lamphun, and theMinistry of CulturedesignatedKarenSpecial Cultural Zoneled to exchange about ownership and the managementof the SAC’s digital resources, as substantial amounts ofresearch are made available to the public through onlinedatabases. How can resources be designed and circulatedin ways that involve source community members as decisionmakersand key users of materials? What if the database inquestion contains ancient Buddhist inscriptions that initiallyseem far-removed from original creators and users? Dr.Hutangkura, who has played a large role in developing theInscriptions in Thailand Database, elaborates, “Now I amthinking about the true owners of the inscriptions. Are theowners the museums and researchers, or are the ownersthe temples where the inscriptions were created, along withthe the surrounding communities that still attach meaning tothese documents? And in what context do the manuscriptsbelong? How can they be distributed so that they are notabused and copied without permission? Many times themanuscripts have been copied without official permissionfrom the temples, and we still don’t have clear laws andregulations about these matters.” Dr. Hutangkura touches onissues that are at the crux of the culture and rights debate,issues that will continue to be deconstructed at subsequentCulture and Rights gatherings.At the second meeting on October 16, Dr. Barryand Ms. Boontinand structured the session around tworeadings that came from presentations made by ElsaStamatopoulou and Richard Wilson at the 2004 CarnegieCouncil. Stamatopoulou attempts to answer the question,“Why cultural rights now?” by outlining international protectionBefore staff at the SAC can integrateculture and rights ideas into projects orshare relevant insight with communitymembers, we first must be able tomake culture and rights meaningful andcomprehensible within our own institution.mechanisms and pointing to the rise in racism, xenophobia,and intolerance across the world, in addition to theemergence of new technologies that facilitate communicationfrom previously-unheard-from source communities. WhileStamatopoulou is a firm believer in the potential of internationalhuman rights instruments to imbue cultural rights with politicalsaliency and mend age-old injustices, Richard Wilson arguesthat the conception of culture upon which these instrumentsare founded is essentialist andflawed. He posits that cultureis only useful as a concept forthinking about society when itis viewed as a transformative,fluid, and open system, whichstands in direct contrast withthe bounded, categorizedconfigurations of culture recognized by Stamatopoulou’s legalframeworks. According to Wilson, the state has no place incultural matters. How can these antithetical perspectivesbe productively reconciled? And how do they apply to theways that the SAC defines culture and assesses the utilityof cultural rights?Perhaps we can begin to answer these questionsby approaching them with knowledge of vernacularization.This concept, advanced by anthropologist Sally Merry, isused to describe the process of appropriation and localadoption of globally generated ideas and strategies. Beforestaff at the SAC can integrate culture and rights ideas intoprojects or share relevant insight with community members,we first must be able to make culture and rights meaningfuland comprehensible within our own institution. This multilayeredvernacularization cannot be accomplished withoutan in-depth understanding of all projects and initiativesencompassed by the SAC, and the forum seeks to providespace and support for such exchange and enhancement.Feedback from the first two meetings is encouraging, andDr. Barry asserts, “I feel hopeful. It seems like a lot of peopleare willing to participate actively and make the connectionsbetween their work, these ideas, and what the Centredoes. It feels very positive and I think we have achieveda consensus on the value of the forum.” The Culture andRights Forum places the SAC in an exciting position tocontribute to the dialogue on the possibilities and parametersof vernacularizing rights that surround heritage & identity,while continuing to develop and evolve as an institution.5

The Third Local Museums Festival 2012:“Cultural Savvy: Local Knowledge Fighting Crisis”by Alexandra DalferroFrom the 23rd to the 27th of November 2012, the Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Center (SAC)organized the Third Local Museums Festival around the theme, “Cultural Savvy: Local Knowledge Fighting Crisis.”When we think about crises that havefaced Thailand in recent years, thefirst events that come to mind aremost likely the 1997 financial crisis, the2004 tsunami, the 2006 military coup,or the widespread flooding of 2011.These incidents received extensiveinternational and domestic mediacoverage, yet the reports generallyfocused on circumstances in andnarratives from central Thailand, andrelied on analysis from a variety ofexperts and public figures to explainevents.If we depend solely on news outlets andpublished materials to learn about crises that influenceThailand, we risk overlooking the insight and experiencesof everyday people across the nation who have used localknowledge to cope with disasters in their communities.Although these challenges that elicit ingenious responsesfrom individuals and communities might not be featured bythe mainstream media, they become woven into collectivecommunity history and identity. As spaces for the displayand safeguarding of these histories and identities, as wellas the objects they encompass, Thailand’s local museumsoffer us a glimpse of how populations from all over thecountry have reacted to both local and national periodsof difficulty. In order to illuminate the stories, approaches,and wisdom that have arisen in times of crisis, the SACinvited sixty-nine local museums from all four regionsof the country to share their perspectives on “LocalKnowledge Fighting Crisis.”6Costumes and props of mor lam performers whoengage in the “kaw khao” tradition were displayedas part of the Mahasarakham University Museumexhibition.The festival was structured thematically aroundfive core ideas. The first core idea focused on “localknowledge versus nature.” Cycles of nature can teachhumans how to live prudently in accordance with local