CAMPUS NEWSLibraries by LariveeMathematics Depart mentHead George Larivee’sefforts to build libraries inrural Nicaragua were featuredin the February 7Boston Globe. After the storyappeared, Globe readers sentLarivee more than $600 tohelp buy books. “At about$5 a book — they’re cheap inNicaragua — that meansanother 120 books for thenewest library in July,”Larivee said.You’ll find a link to thestory in the news archive atwww.concordacademy.org.The Globe’s Web site,www.boston.com, also ranan inter viewwith Larivee onan audio showcalled Acrossthe Divide.Art DuritySharing ADiverse ExperienceCathy Nam ’09 attended theStudent Diversity LeadershipConference in Boston, alongwith Jamie Fradkin ’10,Elizabeth Hoffman ’09, CyHossain ’09, Carrie Hui ’08,Justin Stedman ’09, andfaculty and staff membersJennifer Cardillo, Peter Sun,Dana Fitchett, and MarieMyers. Cathy, cohead ofDiversity at CA, reflected onthe experience:My thoughts came to ahalt as I walked throughthe doors and saw an audi -torium with close to 9,000participants in the People ofColor Confer ence and theStudent Diversity LeadershipConfer ence (SDLC). At thatmoment, I knew that I had justjoined a new community workingtoward a common goal: topromote diversity at each ofour private schools.I was getting jittery justlooking around and feeling allthe energy in the room. Thenthe opening ceremony started,and a speaker mentionedthat 3,446 students wereattending the SDLC—a historicnumber. Writer Frank Wucame up on stage, skillfullyread the energy in the room,and shared personal anecdotes.He explained how oftenpeople complain to him thatwe talk excessively aboutdiversity. “We get it!” theytell Wu. “We shouldn’t beracist nor should we be homophobic!We’re all special inour own way, and we shouldrespect one another.”Wu recounted theresponse he has given toomany times: “Nobody complainsabout having to voteevery four years for a newpresident, because they allknow that democracy is aprocess. We can’t just stopone day and complain thatdemocracy takes too much ofour time, and not vote for anew president. It’s the samewith diversity. We need tocontinuously reeducate ourselves to appreciate what wehave . . . And if you’re sick andtired of talking about diversity,have you ever given a thoughtto those who suffer fromracism, homophobia, andother forms of discriminationon a daily basis?”That was the moment ithit me. I have heard from anumber of people that diver -sity is frustrating since it’s aprocess and we can’t see theend result easily. It made somuch more sense comparingdiversity to democracy. Wuwas right: nobody complainedabout their civic duty to vote,why should they grumble atany mention of diversity?Slam poet Kip Fulbeck andjournalist and author MariaHinojosa also spoke with somuch energy that all of the sixCA students who attended theconference were excited toshare similar experiences withthe CA community and to welcomemore diversity speakersto Concord Academy.—Cathy Nam ’09Planning AheadWhen Head of School Jake Dresden announced in Januarythat he will retire from Concord Academy after the2008–09 school year, CA’s Board of Trustees began plans to findhis successor. The Board created a search committee—comprisedof trustees, staff, faculty, alumnae/i, and parents—that isworking with the Boston-based firm of Isaacson, Miller to findCA’s next head of school and to ensure a smooth transition.Head of School Search CommitteeCOMMITTEE COCHAIRSPeter Blacklow ’87, TrusteeMary Malhotra ’78, p’10, TrusteePoetry HonorsPeter Boskey ’08 was one oftwo high school studentsto receive the Helen CreeleyAward for student poets fromthe Creeley Com mittee ofthe Acton Memorial Library,allowing him to read his poetryat a ceremony honoring JohnAshbery, who received thelibrary’s Robert Creeley PoetryAward in March.Applicants submitted fivepoems, and a dozen finalistswere invited to audition.Olivia Fantini ’10 also competedand made it to the finalround of auditions. As part ofthe award, Concord Academy’sJosephine J. Tucker Libraryreceived $250 to buy poetrybooks.Peter read his five poemsat the event, including “TheVictor,” below.CONCORD ACADEMY MAGAZINE SPRING 20086COMMITTEE MEMBERSElizabeth Ballantine ’66, TrusteeJanet Benvenuti p’09Jennifer Cardillo, Assistant Dean of Community and EquityEllen Condliffe Lagemann ’63, President, Board of TrusteesJohn Moriarty p’02, ’05, ’07, TrusteeJamie Morris-Kliment, Modern and Classical Languages Department HeadMarion Odence-Ford ’82, President, Alumnae/i AssociationDavid Rost, Dean of Students and Community LifeJudi Seldin, Chief Financial OfficerJorge Solares-Parkhurst ’94, TrusteeLearn about the head of school search at www.concordacademy.org/search.The Victor by Peter Boskey ’08She wants to know his psychology, so she tries picking at his thoughtswith imported chopsticks and eagle-eyes. And he complies, surrenderingvolumes of thought and memories, once recorded on pages of diaries.She wants to learn his way, so she follows him from day to night, hidingin fright, because he stops his walk home to turn around. She steals hisshadow, given life by the moonlight reflecting off plastic windows.She wants to be his one, his only, who is around until the world is done;when Armageddon rips and slices at the world’s spices of life. She has won thiswar of, for, and about the heart that won’t part with something good.

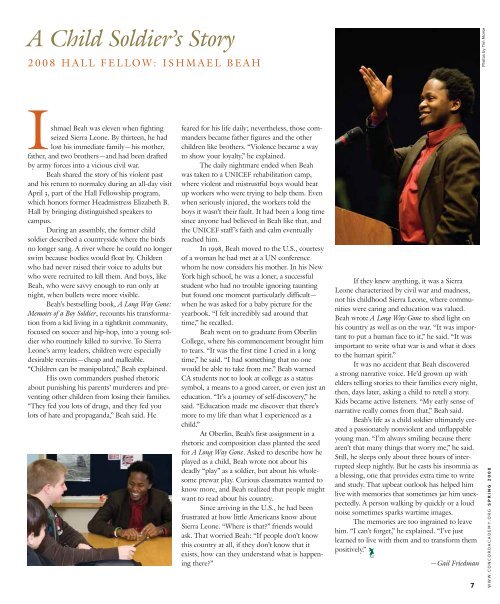

A Child Soldier’s Story2008 HALL FELLOW: ISHMAEL BEAHPhotos by Tim MorseIshmael Beah was eleven when fightingseized Sierra Leone. By thirteen, he hadlost his immediate family—his mother,father, and two brothers—and had been draftedby army forces into a vicious civil war.Beah shared the story of his violent pastand his return to normalcy during an all-day visitApril 3, part of the Hall Fellowship program,which honors former Headmistress Elizabeth B.Hall by bringing distinguished speakers tocampus.During an assembly, the former childsoldier described a countryside where the birdsno longer sang. A river where he could no longerswim because bodies would float by. Childrenwho had never raised their voice to adults butwho were recruited to kill them. And boys, likeBeah, who were savvy enough to run only atnight, when bullets were more visible.Beah’s bestselling book, A Long Way Gone:Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, recounts his transformationfrom a kid living in a tightknit community,focused on soccer and hip-hop, into a young soldierwho routinely killed to survive. To SierraLeone’s army leaders, children were especiallydesirable recruits—cheap and malleable.“Children can be manipulated,” Beah explained.His own commanders pushed rhetoricabout punishing his parents’ murderers and preventingother children from losing their families.“They fed you lots of drugs, and they fed youlots of hate and propaganda,” Beah said. Hefeared for his life daily; nevertheless, those commandersbecame father figures and the otherchildren like brothers. “Violence became a wayto show your loyalty,” he explained.The daily nightmare ended when Beahwas taken to a UNICEF rehabilitation camp,where violent and mistrustful boys would beatup workers who were trying to help them. Evenwhen seriously injured, the workers told theboys it wasn’t their fault. It had been a long timesince anyone had believed in Beah like that, andthe UNICEF staff’s faith and calm eventuallyreached him.In 1998, Beah moved to the U.S., courtesyof a woman he had met at a UN conferencewhom he now considers his mother. In his NewYork high school, he was a loner, a successfulstudent who had no trouble ignoring tauntingbut found one moment particularly difficult—when he was asked for a baby picture for theyearbook. “I felt incredibly sad around thattime,” he recalled.Beah went on to graduate from OberlinCollege, where his commencement brought himto tears. “It was the first time I cried in a longtime,” he said. “I had something that no onewould be able to take from me.” Beah warnedCA students not to look at college as a statussymbol, a means to a good career, or even just aneducation. “It’s a journey of self-discovery,” hesaid. “Education made me discover that there’smore to my life than what I experienced as achild.”At Oberlin, Beah’s first assignment in arhetoric and composition class planted the seedfor A Long Way Gone. Asked to describe how heplayed as a child, Beah wrote not about hisdeadly “play” as a soldier, but about his wholesomeprewar play. Curious classmates wanted toknow more, and Beah realized that people mightwant to read about his country.Since arriving in the U.S., he had beenfrustrated at how little Americans know aboutSierra Leone. “Where is that?” friends wouldask. That worried Beah: “If people don’t knowthis country at all, if they don’t know that itexists, how can they understand what is happeningthere?”If they knew anything, it was a SierraLeone characterized by civil war and madness,not his childhood Sierra Leone, where communitieswere caring and education was valued.Beah wrote A Long Way Gone to shed light onhis country as well as on the war. “It was importantto put a human face to it,” he said. “It wasimportant to write what war is and what it doesto the human spirit.”It was no accident that Beah discovereda strong narrative voice. He’d grown up withelders telling stories to their families every night,then, days later, asking a child to retell a story.Kids became active listeners. “My early sense ofnarrative really comes from that,” Beah said.Beah’s life as a child soldier ultimately createda passionately nonviolent and unflappableyoung man. “I’m always smiling because therearen’t that many things that worry me,” he said.Still, he sleeps only about three hours of interruptedsleep nightly. But he casts his insomnia asa blessing, one that provides extra time to writeand study. That upbeat outlook has helped himlive with memories that sometimes jar him unexpectedly.A person walking by quickly or a loudnoise sometimes sparks wartime images.The memories are too ingrained to leavehim. “I can’t forget,” he explained. “I’ve justlearned to live with them and to transform thempositively.”—Gail Friedman7<strong>WWW</strong>.<strong>CONCORDACADEMY</strong>.<strong>ORG</strong> SPRING 2008