Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

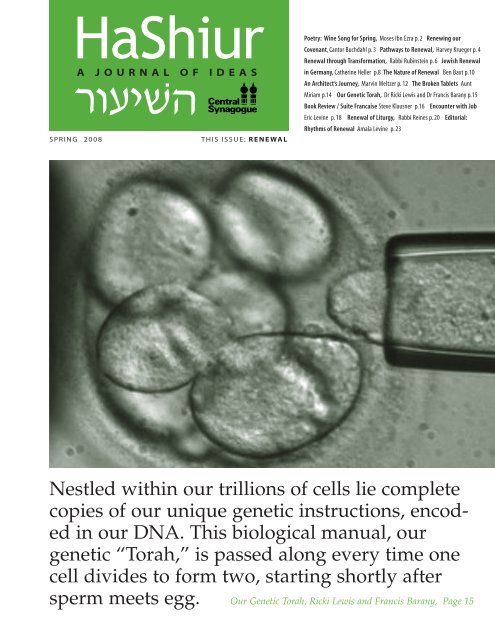

SPRING 2008THIS ISSUE: RENEWALPoetry: Wine Song for Spring, Moses Ibn Ezra p. 2 Renewing ourCovenant, Cantor Buchdahl p. 3 Pathways to Renewal, Harvey Krueger p. 4Renewal through Transformation, Rabbi Rubinstein p. 6 Jewish Renewalin Germany, Catherine Heller p.8 The Nature of Renewal Ben Baxt p.10An Architect’s Journey, Marvin Meltzer p. 12 The Broken Tablets AuntMiriam p.14 Our Genetic Torah, Dr Ricki Lewis and Dr Francis Barany p.15Book Review / Suite Francaise Steve Klausner p.16 Encounter with JobEric Levine p. 18 Renewal of Liturgy, Rabbi Reines p. 20 Editorial:Rhythms of Renewal Amala Levine p. 23Nestled within our trillions of cells lie completecopies of our unique genetic instructions, <strong>encoded</strong>in our DNA. This biological manual, ourgenetic “Torah,” is passed along every time onecell divides to form two, starting shortly aftersperm meets egg. Our Genetic Torah, Ricki Lewis and Francis Barany, Page 15

2POETRYMoses Ibn EzraWine Song for SpringThe cold season has slipped away like aShadow. Its rains already gone, itsChariots and its horsemen. Now theSun, in its ordained circuit, is at theSign of the Ram, like a King recliningOn the couch. The hills have put onTurbans of flowers, and the plain hasRobed itself in tunics of grass and herbs;It greets our nostrils with the incenseHidden in its bosom all winter long.Drink all day long, until the day wanesAnd the sun coats its silver with gold;And all night long, until the night fleesLike a Moor, while the hand of dawnGrips its heel.Moses Ibn Ezra (c. 1055 – after 1135), born in Granada, was a poet andtheoretician.He wrote The Book of Conversations and Memories, a historyof Andalusian Hebrew poetry. In addition to long secular poems, shorterlove poems and meditations, he composed many liturgical poems,including deeply moving selihot.Give me the cup that will enthrone myJoy and banish sorrow from my heart.The wine is hot with anger; temper itsFierce fire with my tears. Beware ofFortune: her favours are like theVenom of serpents, spiced with honey.But let your soul deceive itself andAccept her goodness in the morning,Even though you know that she will beTreacherous at night.Top: View of GranadaLeft: A frieze of vine leaves in theTransito Synagogue, Toledo, 1366.

3ESSAYReflections on ShavuotRenewing our CovenantCantor Angela Warnick BuchdahlShavuot commemorates one ofthe most important theologicalmoments of Jewish life,the receiving of Torah atSinai. However, Shavuot may beour most neglected festival. Sincethis holiday does not have anyexperiential rituals like a Seder orthe building of a sukkah, it has notcaptured the imagination or attentionof our community. Shavuot isworth another look, for its significanceoffers much in the way ofrenewing our own faith.Shavuot began, like mostmajor festivals, primarily as anagricultural holiday. A late springfestival, Shavuot marks the gatheringof the first fruits of the harvest.These bikkurim, or offerings, arebrought to God in thanksgiving andwith hope for an abundant harvestthroughout the summer. This agriculturalpractice also has a spiritualdimension: We are to bring the first,and best, of ourselves when wewant to show gratitude and appreciation,not that which is leftover.The harvest festival isreflected in the Book of Ruth, thetraditional text read on Shavuot.Ruth is the story of a Moabitewoman who marries into anIsraelite family. After her husbanddies, she refuses to leave Naomi,her mother-in-law, and pledges loyaltynot only to her, but to her people,her faith and her God. Ruth isheld up as the paradigmatic convertto Judaism. Just as I am inspiredby every story about people whochoose to embrace Judaism, thiscentral text of Shavuot renews ourfaith by setting an example of ultimateloyalty and devotion.In addition to the agriculturalsignificance of the holiday,Shavuot also marks the historicalmoment when we received Torah atSinai. However, we are told not toremember this as ancient history,but to recreate the moment of Sinaiin each of our lives, by continuingto affirm Torah. It is said that thecovenant is a covenant for all generations,which means that eachgeneration must take on thatcovenant anew, in some waysfollowing the model of Ruth. WhileRuth had to leave her ancestralfaith to accept the Torah of ourpeople, in contrast to born Jewswho do not, she reflects a reality inour world today — that we are allJews by Choice.We live in a time ofunprecedented freedom and opportunity,which means that Jews inAmerica today have the freedomto study and embrace Torah, butalso NOT to. Every time I pass theTorah through the generations to anew Bar or Bat Mitzvah, each timeI bless a confirmand, I am awarethat their embrace of Torah is anaffirmation of choosing Judaism.So how have Jews madethe festival of Shavuot an opportunityto affirm the role of Torah intheir lives? A ritual that hasbecome popular at Shavuot is toengage in a late-night study session,called a Tikkun L’eil Shavuot,on the eve of Shavuot. Tikkun literallymeans “repair” and reflects themystical notion that by studyingTorah, we are in some ways notonly mending and healing whatmight be missing in our own lives,but helping to mend the world.In Eastern Europe, a fewhundred years ago, Jews began thepractice of introducing young students,between the ages of threeMarc Chagall, Ruth and Boazand five, to the study of Torah atShavuot. The Reform movement,in its early years, also understoodthe fundamental significance ofrenewing our commitment to Torahat Shavuot and began the practiceof Confirmation for students,generally in the tenth grade. TheReform movement felt that studentsat this age were better able tomake a more mature commitmentand conscious choice.Central Synagogue beganConfirmation services in 1868 and,to this day, we continue to holdthem for our tenth graders onErev Shavuot. It renews my faithevery year to watch each of thesestudents, after years of seriousstudy, offer a statement of theirfaith, and offer their bikkurim, theirfirst fruits, as they lead the service.I recognize I am witness to anothergeneration of Jews who, like Ruth,have taken the covenant of ourfaith into their lives.■

4HISTORYIsraelPathways to RenewalHarvey M. KruegerIfirst went to Israel in 1961, as ayoung associate at Kuhn Loeb,to work on the external financingof an Israeli bank; it wasthe first public offering of an Israelicompany in the international capitalmarkets. My initial impressionsof Israel were not all that positive.1961 was the year that BenGurion was traveling aroundEurope insisting that you could notbe a good Jew unless you madealiya. Wherever I went I was proselytized,whether at the Dead SeaWorks (now Israel Chemicals) orover lunch at a refinery on theshores of Lake Tiberius, despite mymaking it quite clear that, marriedand with family, I had no intentionof moving to Israel. In addition, Ihad an encounter with an abrasiveshopkeeper in Jerusalem whoaccused me of trying to bargainwith her, when all I wanted was tobuy a Kiddush cup for a friend atthe price she had quoted him. Herbehavior epitomized to me all thecoldness, unfriendliness and stubbornnessof Jerusalem.I was absolutely wrong.The following year I wentback to Israel to arrange a financingfor another Israeli bank. Late oneafternoon, as I was walking back tomy hotel along, what is still today,one of the most crowded streets inTel Aviv, I found myself intentlystudying people’s faces. I did notknow why, but it occurred to methat I was looking for family. ThenI stood stock still, quite literallystruck by the idea that I was actuallylooking for myself. It has been along time since, but through Israeland because of Israel, I know whoI am and what I am.I have devoted a large partof my life since then to the wellbeingof Israel. I realized that Icould contribute in two areas: educationand as an investment banker.I knew Israel needed to achieveeconomic independence and, in acountry virtually devoid of naturalresources (other than the Dead Seaminerals), it was clear that Israelwould have to rely on its largestnatural resource, the intellect of itspeople. But that intellect must bemined and refined, like any othernatural resource, and the place inIsrael for such activity is a qualityeducational system, particularly atits highly regarded universities.Only this could ultimately lead toIsrael’s economic independenceand viability.Then I stood stock still,quite literally struck by theidea that I was actuallylooking for myself.In 1972, I began a longinvolvement with the HebrewUniversity of Jerusalem, becomingits chairman in 1983, only to discoverthat the University wasessentially bankrupt. It took thenext nine years of my tenure to turnthe tide from red to black, but it hasremained in the black ever since.On the business side, I continuedthe work with the banks Ihad begun in the 1960’s. But thereis a vast difference between Israel’seconomy in those days and that oftoday. Then it was still a countryof pioneers with a small economy,demand consistently exceedingsupply, and there was chronic overemployment,leading to inflationand a disregard for efficiency; therewas a cultural disdain for profits assomehow unethical. The countrypersisted in ignoring these issues inthe belief that a certain amount ofinflation was healthy, and efficiencydid not matter as long as everyoneworked. But inflation kept creepingup steadily, finally reaching a catastrophic500 % +/- in the early 80’s.In addition, Israel’s industry wasbasically owned either by Histadrut(the Federation of Labor), thegovernment or the banks. The oldsocialist attitude of disregard forefficiency and profits was stilloperative.Following the 1973 war, thesubsequent concerns about “petrodollars” and the Arab boycott offirms doing business with Israel,the few other international bankerswho had been intermittently activein Israel left, and I was the onlyremaining international investmentbanker. Business was difficult; we

5(Kuhn Loeb and Lehman mergedat the end of 1977) financed theHadera power plant and manageda substantial number of Israeli governmentor government-relateddebt offerings over the years, butthere were no equity offerings andnot much foreign investment. By1983, Israel was in the midst of amajor financial crisis; the majorIsraeli banks experienced such asevere crisis that they were nationalizedby the government. Thecrisis lasted for several years andby 1985-86 a series of draconianreforms, despite causing a numberof businesses to go under, neverthelessreduced inflation dramatically,stabilized Israel’s currency and formulatedcomprehensible and stabletax policies.These latter two pointswere extremely important. Strategicand financial investors are generallywilling to assess business riskson their own, but are reluctant toinvest where the risks are entirelyin the control of others. Tax policyand currency stability are twosuch risks.The reforms worked and,in 1987, Lehman was able to managesuccessfully two corporateequity offerings. The result wasin the case of one of them, the US$33 million offering for TevaPharmaceuticals, extraordinary andan omen for the future: one thirdof the offering was sold in the ordinarycourse of the distribution tonormal institutional investors in theUnited States and elsewhere. Thiswas the first time any institutionalinvestors had invested in Israelequity!That effort in 1987launched Israeli entry into theinternational equity markets, withthe result that Israel today vieswith Canada as to the largest numberof foreign issuers listed onUnited States stock exchanges.It also gave confidence to privateinvestors to invest larger and largeramounts in Israeli companies,especially in the technology andhealth care industries, and led tothe creation of Investment FundsAbove left:Early development ofthe Dead Sea Works andIsrael Chemicals today.Above:Student at HebrewUniversity, Jerusalem.Left:Managing partnersof Teva Pharmaceuticalsat NASDAQ.for investing in Israel securities,both in and outside of Israel.Bond offerings, of course,continued apace. Indeed, in 1996,we did an offering for the government-controlledIsrael ElectricCompany. It included a substantialtranche of 100 year bonds; this wasboth economically and psychologicallysignificant, because nowIsrael could say: “Look, the marketsbelieve we are here to stay”.In the aftermath of thebanking crisis and the reforms inthe mid 1980’s, investors havegained confidence in Israel’s economicstability. Events have provedthat the government is able to controlinflation and maintain a stabletax system. The Shekel has recentlyimproved its value against thedollar, the Euro and many othercurrencies. The GNP has beengrowing at 5% per year for severalyears and inflation has been hoveringaround zero for a couple ofyears. All this despite an unstablepolitical environment and hostileneighbors.The shibboleth that Israelisare good entrepreneurs but notgood managers, is clearly false.In fact, they are great managers andmost of them are educated in Israel.Despite periodic brain drains anda hostile environment, Israel is anexciting and dynamic country,constantly changing, constantlyrenewing. Just consider how it hasevolved from a financial backwaterin the 60’s to the buoyant, stableeconomy of today. It is an incrediblesuccess story.The 100 year Israel Electricbonds mature in 2096 and I haveno doubt that they will be paidin full!■Harvey M. Krueger, who had been president and CEO ofKuhn Loeb until its merger with Lehman Brothers,became Vice Chairman of Lehman Brothers Inc. and isnow Vice Chairman Emeritus.

6ESSAYReflectionsRabbi Peter J. RubinsteinRenewal through TransformationNearly a decade ago, on ErevShabbat August 28, 1998,the sanctuary of CentralSynagogue was devastatedby fire. It was a painful evening asour members and strangers lookedon. Flames and smoke lapped atthe overhang of the building’s roofbefore the roof caved in, smashingto the sanctuary floor beneath. As Istood there, I remembered the photosI had seen of Kristallnacht, whenmarauding Germans ransacked andburned synagogues across the countryin November 1938. I also recalledthe historic image of the destructionof the Temple, the centerpiece ofIsraelite worship, by the Romans in70 CE. The Germans eradicated millionsof Jews, the Romans tried tosubdue them, and sanctuaries havebeen destroyed by fires, but Jewshave survived , rebuilt and neverceased to worship. This continuationof Jewish life is supported bytwo factors.The first is conceptual:Jews believe in “resurrection”(t’chiyat ha-matim). Our forebears,thousands of years ago, were convincedof the resurrection of thedead. Death was simply a transitionto another life in the olam ha-ba,the world to come. Though a significantportion of the Jewish communityto this day continues to praiseGod: “You are faithful to revive thedead. Blessed are You, O Lord, whorevives the dead,” we in theReform movement had disownedthis fundamental and traditionalportion of our daily liturgy. Instead,Reform Judaism replaced literalresurrection with eternality of thespirit, substituting for the originaltext: “Praised are You, O Lord, whohas implanted within us eternallife.” Mishkan T’filah,the Reform movement’srecently publishedprayer book,which we now use inour congregation, providesan alternativereturn to the traditionalmeaning: “Blessedare You, Adonai, whorevives the dead.”The secondfactor is historic:The Roman conquestwould not vanquishus. We could andwould rise again.According to the traditionalliturgy, Godwould return us toJerusalem and therewould be rebuilt “aneverlasting structure”in which God woulddwell. The physicaldestruction ofJerusalem and of theTemple would not bea cause for abandoningour existence andabiding mission. Webelieved we would arise. The historicagent of this process of renewalwas Yochanan ben Zakkai. Heprevented the disappearance ofour people. He is my hero.Rabban Yochanan benZakkai lived during the first centuryof the Common Era (CE), whenthe Romans ruled Judea, the presentIsrael, and their emperors usedtheir conquered and subservientprovinces to supply the fundsneeded to support the vast Romanarmy. Our forebears chafed underRoman economic and politicaloppression and periodic rebellionsPaul Klee, Destruction and Hopeerupted. Rome did not toleratesuch revolts; consequences wereimmediate and devastating, asindicated both by the gospel narrativesof the treatment of Jesus andby Josephus’ history of the siegeat Masada (73 CE).Yochanan was born intothis environment. We know that helived and studied in the Galilee, thenorthern part of present-day Israel,and that he returned to Jerusalemas a political follower of the liberaland renowned teacher Hillel. Atthat time, in the latter half of the

7first century CE, Jerusalem was ahotbed of competing ideologicalcamps advocating conflicting policieshow to deal with the Romans.The Sicari, the most extreme Jewishzealots, their name derived fromthe sica (a short dagger), wanted noaccommodation with Rome andkilled Roman officials as well asJewish partisans of Rome.Yochanan had family ties to thezealots. His nephew Abba Sikraheaded the Biryonai, a zealot factioncommitted to armed battle withRome. He is reported to havetorched the provisions that hadbeen stockpiled by the Judeans inpreparation for the siege imposedby Rome. Abba Sikra rationalizedthat, by destroying the supplies ofhis own people, the Jerusalemiteswould be compelled to battle theRomans.The Roman conquestwould not vanquish us.By contrast, Yochanan, onthe opposite side of the politicalspectrum, was willing to accommodateto Roman rule. In fact, he, aPharisee, did not believe in thesupreme prominence of Jerusalemas a sacred city. While he did notseek the destruction of Jerusalem,he was also not prepared to sacrificeJewish life in defense of thecity. To Yochanan, Jerusalem representeda system of practice and ritualthat he and the Pharisees foundincreasingly irrelevant and abhorrent.The crux of the story, whichmay be difficult for us to understand,is that Yochanan did notromanticize the Torah system ofsacrifice, Temple and priesthood.He had concluded that Jerusalem,while a symbol of Judean statehood,was no longer central toemerging Jewish life. The sacrificialcult of animal and harvest offeringsthat had been appropriate for anagricultural society, were no longermeaningful for a growing urban,artisan, merchant population livingin Jerusalem and other towns. As aresult, the Temple in Jerusalemitself seemed no longer central,except as a symbol. Though thepriesthood was still held in historicalesteem, it was increasinglydebunked by a population thatviewed the priests’ excessivelifestyle and political pandering asmorally wrong. They were exasperatedthat priests, having been borninto their position, were notrequired to demonstrate eithermerit or ability. Sharing theseviews, Yochanan ben Zakkai wasboth philosophically and literallyprepared to abandon Jerusalem andthe sacrificial/priesthood/Templesystem it represented. This is whyhe initiated a revolution.When, in 67 CE, the RomanGeneral Vespasian, with 60,000troops, launched a brutal campaignto subdue Galilee and to destroyJerusalem, the story tells thatYochanan had himself smuggledout of Jerusalem in a coffin. Thoughwe might conclude that his escapewas intended to deceive the Romantroops besieging Jerusalem, thesesoldiers had no reason to preventabandonment of the city. The ruseof a fake burial was more likelyintended to dupe the zealots whowould have killed any countrymenleaving the city.Once outside, it is written,“Yochanan reached Vespasian andgreeted him with a royal greeting.Vespasian remarked, ‘You give mea royal greeting, but I am not aking; and should the king hear of ithe will put me to death.’ Yochanananswered, ‘If you are not the king,you will be eventually, because theTemple will only be destroyed by aking’s hand’….”Three days later a messengerarrived with the news that theRomans had proclaimed Vespasianking (Emperor of Rome). Vespasianthen said to Yochanan, “Make arequest of me and I will grant it.”Yochanan answered, “I ask nothingof you except the town of Yavneh,where I might go and teach my disciplesand there establish a prayerhouse and perform all the commandments.”The Romans honoredhis request. Then they proceededwith the siege and destruction ofJerusalem, its citizens and itsTemple. By some estimate the finaldeath toll of the First Jewish-Roman War ranged from 600,000 to1.3 million Jews.But Yochanan and hisdisciples established in Yavneh,the refuge granted by Vespasian,an academy and a court of rabbis,that assumed the decisions andauthority once held by the priesthood.Incrementally, Yochanancreated the institutions that arethe foundation of the Judaism weknow. Because of Yochanan’svision, the synagogue became thecenter of Jewish life, rather than thesingle Temple in Jerusalem. Rabbis,rather than priests, became leadersof the community. Prayer becamethe core of worship, replacing thesacrificial cult. Our rituals of worshipnow are vastly different fromthose directed in the Torah.I sometimes imagine thatif the Romans had not destroyedthe Temple, Jews ultimately wouldhave condemned to oblivion aninstitution that was becomingincreasingly irrelevant to their lives.Today we are grateful to RabbanYochanan ben Zakkai for his heroicrevolution that shaped andchanged Jewish history and worshipin the most profound way. ■

8TRAVELBearing WitnessJewish Renewal in GermanyCatherine HellerWhen Rabbi Rubinstein leda group from CentralSynagogue to Berlin andPrague in 2007, it was amore complicated trip than theones to Israel or Argentina. Thedecision to go to Germany isjudged in ways few travel plansare. But Rabbi Rubinstein isadamant that Jews should visit theplaces where they once lived andwere persecuted, because we needto bear witness to their exterminationby the Nazis and acknowledgethe past.Another compelling reasonfor visiting Germany now is therenewal of Judaism which, sincethe fall of communism and thereunification of the country in 1989,is fed mainly by immigrants fromthe former USSR and Israel. It is thefastest growing Jewish communityin the world. Since many of theseJews were raised in a state wherereligion was suppressed, they needto be exposed to liberal Judaism.As a result, the Reform movementfounded Geiger College, a seminaryin Berlin. The first class graduatedin June 2007 in a ceremonyattended by Chancellor AngelaMerkel and other German dignitaries.It is a marvel to have rabbisordained in Germany now and toTop: Brandeburg Gate Above: First graduating class ofthe new Geiger Rabbinical School in Berlin.Left: The new synagogue in Dresden.Far right top: Plaque giving the name of the formerJewish resident. Far right bottom: Bricks engraved withnames of destination points at railroad station in Berlin.have congregations ready and waitingfor them. We attended Shabbatservices at a congregation housedin an old US Army chapel. About50 congregants, together with ourgroup from Central Synagogue,participated in services that wereheld both in German and Hebrew.Berlin is a difficult city todislike, even for a traveler withprejudices. It is a thriving city, withexciting new architecture, wellrestored old buildings, clean streets,manageable traffic, great restaurants,museums, art galleries, andshopping. Potsdamer Platz, once ano-man’s land between East and

9West Berlin dotted with explosivemines, is now an energetic commercial,entertainment and residentialsquare with movie theaters, afilm museum and a beer hall.Our group stayed at theAdlon, a gracious hotel near theBrandenburg Gate. Thousands ofgoose-stepping Nazis oncemarched through this imposingarch topped by its horse drawnchariot. Then it became the borderbetween East and West Berlin, andnow it is a landmark in a swankyneighborhood, the end of a boulevardwith the lovely name of Unterden Linden.Close to the BrandenburgGate is the Holocaust Memorial,designed by American architectPeter Eisenman. The vertigo inducinglabyrinth of blank, uneventombstones takes up nearly a wholecity block, together with a documentationcenter in an undergroundbunker. The memorial is ina bustling part of the city thatBerliners pass all the time. As areminder of what happened 70years ago, sidewalks all over thecity are dotted with small brassplaques in front of many homes,giving the names of the Jews whohad lived there and the dates theyhad been deported. No one nowvisiting or living in Berlin canescape knowledge of the genocide.The Daniel Liebeskind designedJewish Museum offers further testamentto the Holocaust and is animportant part of any visit to Berlin.For many in our group, themost significant stop in Germanywas the suburban railway station atGrunewald, about seven miles outsideBerlin. From this depot, hundredsof freight trains packed withJewish deportees left for the concentrationcamps. Clutching theone suitcase they were permitted totake, Jews were marched throughthe streets of Berlin to this stationlocated in a wealthy, stately suburbwith comfortable homes, majestictrees and well kept gardens. Nazirecords provided the details for theengraved bricks now lining the stationplatform that list the dates,destinations and numbers deportedin each transport. For example,“February 10, 1941: 741 toAuschwitz,”, “ February 12, 1941:402 to Theresienstadt,”, “ February15, 1941: 801 to Belsen-Bergen”....The march of the desperate did notjust happen once or twice, but continueduntil 1945 and the residentsof Berlin must have known that theJews were disappearing.At the Grunewald station,we were joined by a class ofGerman school children, several ofwhom were of Asian and Turkishancestry. Despite their initial whispering,squirming and shoving, theteacher made sure that the 10 or 11year-old students saw the bricks andunderstood her somber explanationof their country’s sordid history.They also saw our shock and grief.Visiting Dresden, we cameacross more evidence of the renewalof Jewish life in Germany. Astriking contemporary synagoguestands in the place where the oldone was destroyed on Kristallnachtin Dresden in 1938. It is the firstnew synagogue in the former EastGermany to be rebuilt since the endof World War II. Only one remnantsurvived from the original structure:a Star of David saved by afirefighter and hidden in his home.It now adorns the entrance to thenew synagogue.It is the fastest growingJewish community in theworld.The synagogue is part ofthe ongoing reconstruction ofDresden, which was fire bombedby the Allies. The local Lutheranminister supported its constructionwhen his own church, as well asthe Catholic cathedral, were beingrebuilt. Today Dresden is a citywith world-class art and jewel collections,filled with great historyand historical anecdotes.The renewal of Jewish lifeis part of the overall renewal inGermany since the wall came downin 1989. Anyone interested inJewish life today, as well as thosewho want to bear witness to a savagepast, should pay a visit toGermany, and especially Berlin,which is a beautiful, livable city,rebuilt after two dark chapters inhistory.■Catherine Heller is a freelance writer who loves to travel.She has been a member of Central Synagogue for over20 years.

10ESSAYA Reverence for all Living ThingsThe Nature of RenewalBen BaxtWe Jews were once indigenous.Long before templesand synagogues,Jewish tradition wasborn in the wilderness. Our ancestorswere moved by the rhythmand phenomena of the natural world.At sunset, darkness fostereduncertainty and doubt.Under the night sky, stars by themillions overwhelmed them.At sunrise, dawn revived clarityand hope.The end of summer promptedingathering and introspection.Spring brought optimism andthanksgiving.The sun and the moon, the dramaof the weather, the extremes of terrain,the mysteries of beginningsand endings, all shaped them. Inour Torah, the elements of natureare key players. Throughout ourexistence, we have told stories inwhich gardens and deserts, floodsand fire, mountains and rivers,storms and droughts are importantingredients.In our Torah, the elementsof nature are key players.A way of life and inherentunderstanding of the world grewfrom that intimate relationship withnature. Influenced by the physicalworld that both nurtured andthreatened, a practical and spiritualwisdom took root and began toevolve. It was a wisdom derivedfrom experiencing the depths ofhardship and the transcendence ofwonder. We began to sense truthsabout life itself and to put our trustin them. It gave birth to an aware-Ben Baxt, Drawingsness of the nature of time and areverence for all living things.As we evolved as a people,the lessons of our shared experiencesbecame codified and ritualized.What was once common wisdombecame religious law. Amongour mitzvot, there is a wide rangeof prescriptions and prohibitions.Some are very specific and literal.One may not drain one’s well if itwill diminish water needed by aneighbor. One may not dispose ofrocks cleared from one’s field in aroad. The wood of fruit trees isprohibited for use in certain implements.Tanneries, threshing andother objectionable activities areprohibited in proximity to homes.In the Book of Numbers, a largeswath of natural, protected land isprescribed to separate city andactive agricultural land beyond.Many dozens of specificsare enumerated in the ShulchanArukh. Their common denominatoris an insistence that we be aware ofthe consequences of our activitiesand be concerned for our neighbor’swell-being. Acting for thecommon good, including valuingthe beauty of the land, was thefoundation for our emerging socialorder. Respect for our shared environmentbecame a logical extension.From the sensitivity foreach other’s well-being, anotherconcept evolved to influence howwe viewed the world. Our ancestorsunderstood the importance ofmoderation and rest to the fosteringof renewal: renewal of the land— renewal of the body — renewalof the spirit. In Leviticus, we arerequired to give the land a completerest every seventh year. Forthe land, the Sabbath year preventeddepletion. For the spirit, it provideda break in routine thatheightened an awareness of ourown dispensability, and our interdependence.Relying on only those

11crops that reappeared withouthuman help, we understood thatsustenance is a gift of nature. TheSabbath year brought us back to amore basic relationship with theland and a gratitude for life.Foremost among all of ourtraditions, the Sabbath day is fundamentalto fostering perspectivein our lives. Our ancestors understoodthe need for renewal andrestoration in every aspect of life.It is compassionate, and it is practical.They understood that rest isessential to health and that thehealth of each life is essential to thehealth of the whole. For those toodriven or insensitive to appreciatethe necessity of renewal, a day ofrest was mandated.Shabbat asks us to lookback at the week that is ending —and look for meaning there. It asksus to look ahead to the week that iscoming — and ponder how to giveit meaning.In the four billion years ofthe earth’s life, we humans arenewcomers. Today, our way of lifehas moved very far from our primalorigins. But our inherenthumanness has not. Though wenow live in a world of solid shelter,assured nourishment, instant news,and high speeds, we still retain thebasic nature of our ancestors.Shabbat helps us return to moving,as they did, in time with Nature’sbreathing and Her heartbeats – theday, the week, the seasons, the year,lifetimes. Gently, She takes us bythe hand to walk in step with Her.In an era when we havebecome more focused on our ownimmediate world, Shabbat beckonsus to engage with the world atlarge, the origin of our spiritualfeelings. Profound wisdom can bederived from being a part of life’smost basic happenings and experiencingits most ancient sensations.The wilderness is where Emet, ethicaltruths, were first revealed andstill are evident everywhere.When we fetch our own water, weunderstand its value.When daylight is our only light, welearn to use it thoughtfully.When unknown noises frighten us inthe dark, we realize we arevisitors in someone else’s home.When new life and decay are intertwined,we begin to understandcontinuity – and eternity.When we are awed by sunrise and anthillsand starlight and birdsong, we begin to sense ourplace in the universe.When we are touched bythe world around us, we come tosee that all life is interconnected.It is a realization that comforts andinspires inner peace. It is a knowingthat nourishes us — a knowingthat renews us. We become moreopen and receptive. Empathy andcompassion come forth.When empathy and compassionfoster healing and restoration,renewal comes full circle andbecomes self-fulfilling. Is that notour life’s work?■When not in the woods, Ben Baxt attends Shabbatmorning services at Central Synagogue. He has beeninvolved in the restoration of the sanctuary andhas helped weave new elements into traditional rituals.An architect, he and Susan live in Brooklyn.Reading Suggestions:Rabbi Comins, Mike, A Wild Faith (Jewish LightsPublishing, 2007) Rabbi Brickner, Balfour, Finding God inthe Garden (New York: Little Brown, 2002) Goodall, Jane,Through a Window (New York: Houghton-Mifflin, 1990)

12INTERVIEWUrban Renewal in New YorkAn Architect’s JourneyInterview with Marvin H. Meltzer, AIAEditor [E.] What prompted you tobecome involved in urban renewalprojects in New York?Marvin H. Meltzer [M.M.] I grewup in St. Paul, Minnesota. Aftergraduating from the University ofMinnesota School of Architecture, Iwas drafted into the Army and wasstationed on Governor’s Island. Itwas and still is a beautiful place. Ihad a direct view of LowerManhattan. It inspired me to stay inNew York to work as an architect.Everyone’s life has a certainjourney and, if you are lucky,you can take hold of it and direct itto where you want to go. There isprobably no other place where Icould have worked and got the samekind of fulfillment as I get here.I thought that myarchitectural careerhad come to ascreeching halt.I first got into the renewalof neighborhoods when the bottomfell out of the real estate marketin the late 1980’s. An architectfriend of mine who worked onhousing for not-for-profits, thehomeless and people with specialneeds, asked me to help him witha design.E.: What was your first project?M.M. Twenty buildings by CrotonaPark in the South Bronx. At thetime, the city owned a lot of devastatedbuildings and vacant landwhere houses had been torn down,and Mayor Koch had initiated anextraordinary program to rehabilitatethem in order to revitalize theneighborhoods.When I worked on thatspecific project, we always neededpolice escorts. It was a scenestraight out of Bonfire of the Vanities,with drug dealers doing briskbusiness right there on the street.I thought that my architecturalcareer had come to a screechinghalt. But then I began to see theopportunities of what I could doas an architect in the South Bronx.Now, it is a vital community withnot an empty shop around.E.: What else did you do in thatarea?M.M. One of the big projects wasMelrose Court, which consisted of 3city blocks of vacant land that oneSouth Bronx in the early 70’s. Top right: Roscoe C BrownJr Apartments. Below right: Melrose Courtof my clients had assembled. I realizedthat here I could do somethingreally powerful and become themaven of low-rise, high densityhousing in the Bronx. The BoroughPresident had envisioned a suburbanenvironment, Westchester-stylehouses with clapboard sidingwhich, to me, was frankly bizarre,because buildings in the Bronx aremostly masonry. Although I createdwhat they wanted, I did it my way,and it ended up transforming thatwhole part of the South Bronx.I designed Melrose Courtas townhouses for local ownership

13entered from the street through ayellow hallway into this quiet innerspace. It really fascinates me howsuch spatial transitions are experiencedas a part of life in New Yorkand how they can be incorporatedinto architectural design.Now we are doing a luxury buildingon 149th and Broadway. Sowithin 30 years, individual neighborhoodswithin the Upper WestSide have undergone renewal indifferent ways that reflect theirchanging communities.and gave them a Disney Worldappearance with flat facades andpeaked roofs, supported frombehind, just like a movie set. Butthen you walk through the façadeinto these magical courtyards,planted and landscaped and youare in another private world. I visualizedthis journey as one experiencesNew York, transitioning fromthe subway, to the busy street andfrom there into your apartment. Alot of what I have done has courtyards,also in Manhattan. Forinstance, on 26th Street, whileretaining the traditional facadewith its fire escapes, I took the middleout of a wide building that isE.: Would you say that urbanrenewal is primarily economicallydriven?M.M. Largely yes, because peopleare always looking for places to livethat they can afford. That is what isdriving the revitalization of Harlempresently. For example, we did awhole city block that had beenvacant on Frederick DouglasBoulevard. The city has very strictguidelines for such urban renewalprojects, and the community alsohas advocates who represent itsneeds and wants. The politics ofcreating development in New Yorkis intense and fascinating, but itworks. The whole area, like theSouth Bronx, is now revitalized andalso, thanks to more ownership, thecommunity has stabilized. Smallerdevelopers then follow as doesmore retail and more people whowant to live near it.When people start movinginto a neighborhood in search of abetter and more affordable livingenvironment, it begins to change.The Upper West Side is a greatexample of this kind of renewal.Today, as many orthodox familiesmove there, the apartments that arebuilt, the shops and restaurantsthat follow, all serve their particularneeds. When I first designed a residentialbuilding on 81st andColumbus in the early 1980’s, thearea was run down and homelesspeople were sleeping on the streets.E.: What other guidelines do youhave to follow when revitalizing abuilding or neighborhood?M.M.: Working in a designated historicneighborhood like the LowerEast Side involves different playersand different rules. It puts restrictionson what you can do, how bigor how high you can build, butvery rarely are restrictions placedon what you can create architecturally,unless the building itself ison the historical register. I havedesigned some very contemporaryhousing in that area. On the otherhand, when I am working with alandmarked building, I have to bevery specific; exteriors and windowshave to be preserved, anddown to the materials used, everythingis prescribed. Landmarks arecontroversial because working withsuch restrictions is usually not economical.But unless people areforced to preserve something, theyusually won’t. Also, preservingthe Lower East Side as a historicdistrict has created economic valueand revitalized shopping and taxincome.E.: Were you involved in therestoration of Chasam Sopher onthe Lower East Side?M.M.: Yes, I was. It is an orthodoxshul in what was historically NewYork’s Jewish neighborhood. Nowit is again attracting young Jewscontinued on page 24

14FABLEA Midrash for People of all AgesThe Broken TabletsAunt MiriamWhen Moses came downfrom the mountain bearingGod’s commandments,he was horrorstricken to see the Israelites worshippingand dancing around theGolden Calf. In a fit of anger, heraised the sacred tablets above hishead and brought them crashing tothe ground, smashing them into athousand pieces.You can imagine how hefelt after spending forty days andforty nights on the mountain top,communing with God and receivingHis covenant, only to find thatwhile away, the people hadbetrayed him. Hadn’t they promisedto obey the commandmentseven before receiving them? Butthey had become impatient andbroken their promise.Even a piece of stone withonly a single letter is holy...After the Golden Calf hadbeen destroyed and those mostresponsible punished, Moses satdown on a rock by the edge of thecamp, feeling weary and utterly forlorn.After all the travails he hadbeen through with the Israelites, allthe suffering they had endured andthe triumphs they had witnessed,was this how it was going to end,right here in the wilderness? Whatmore would it take to make thispeople trust in God and keep thattrust? And why had God urgedhim to take on this task, against hiswishes, if it was to end like this, atask impossible to achieve?As he was turning overthese troubled thoughts in hismind, he noticed that a crowd ofchildren had gathered at the foot ofthe mountainjust wherehe hadsmashed thetwo tablets.Curious tofind out whatthey weredoing, hemade his waytowards them.Some of themwere scrabblingin thesand whileothers wereemptyingtheir pockets.“What areyou doing,children?”Moses asked.“We’recollecting thepieces ofstone,” repliedone of thetaller boyswith tousledred hair whoappeared to be their leader.“Why are you doing that?”Moses asked.“Well, sir, you told us youwould be bringing us God’scovenant. So we thought that wasexactly what was on those stonetablets you smashed.”“And if we’re right,”another boy interrupted, “then thosebroken pieces of stone must be veryholy since they contain words fromGod.”“Even a piece of stone withonly a single letter is holy,” a littlegirl said.“And when we’ve collectedRembrandt van Rijn, Moses Smashing the Tablets of The Lawall the broken stones, we’re goingto put all the pieces together,” theleader interjected. “We know that’swhat God would want.”“You know, children, that’sa beautiful thought and a wonderfulthing you are doing,” Mosesreplied. “Now it may be difficultfor you to find all the pieces andput them back together, but don’tlet that stop you. For what you aredoing is very important. Before Isaw you here, I was feeling verysad, as though all my work hadended in failure. But you’ve mademe realize that we must nevercontinued on page 17

15SCIENCEThe Power of Stem CellsOur Genetic “ Torah”Ricki Lewis and Francis BaranyNestled within our trillions ofcells lie complete copies ofour unique genetic instructions,<strong>encoded</strong> in our DNA.This biological manual, our genetic“Torah”, is passed along every timeone cell divides to form two, startingshortly after sperm meets egg.Yet cells take from that manualonly what they need to surviveand specialize: a muscle cell readsthe blueprints to contract but notcommunicate; a nerve cell does theopposite.Building our bodiesrequires stem cells. They provide theraw materials to sculpt our embryonicselves, giving rise to the tissuelayers that emerge from featurelessballs of cells. As tissues fold andcontort into organs, a human-likeform gradually takes shape.Stem cells continue todivide to supply new cells as thefetus blossoms towards birth. Andafter that spectacular event, fordecades, stem cells tucked intopockets of our parts — in ourbrains, hearts, livers, and more —keep pumping out cells. While cellsat our surfaces accumulate variousinsults and are easily shed, stemcells come to the rescue if we sufferinjury or disease. Stem cells mayreawaken and begin dividing at adisaster site, filling in tissue, or berecruited from the bone marrow toassist in the replenishment.Courtesy of stem cells, wegrow. We heal. Yet for some of us,an errant stem cell divides toooften, or a specialized cell reverts tostemness and divides unchecked.Instead of filling in tissue or propellingnormal growth, a tumorforms. Researchers are finding thatmany cancers are rooted in stemcells that have gone to the darkside, becoming cancer stem cells.Stem cells are powerful.But when the media trumpet themiraculous stem cells that can“turn into any cell type of thebody,” they’ve got it wrong. Stemcells do something far more important:They “self-renew,” in the lingoof the biologist. Each time a stemcell divides, it spawns another ofitself, so we can keep making newcells. It also produces progenitorcells, which in turn divide to yieldthe cells that specialize.We need our stem cellsand their marvelouscapacity for self-renewal.The mantra, in stem cellspeak,is “potential.” The descendantsof a stem cell in an earlyembryo can specialize as anything.As time goes by, possibilities narrow,much as a college studentselects a major. In our bodies, progenitorcells have more limitedpotential, and specialized cells evenless. Our brain cells stop dividingwhen we are children — except fora few stem cells hugging the fluidfilledcavities in the middle of ourbrains. We harbor stem cells in ourteeth, hair roots, salivary glands,and fat. Some are inevitably discardedas medical waste.We need our stem cells andtheir marvelous capacity for selfrenewal.Without them, we’d neverdevelop beyond fertilized eggs. Sowhy not tap their talent for renewal?That’s the basis for the use of stemcells in regenerative medicine, andis already routine for bone marrowand umbilical cord blood stem cells.Sources of stem cells rangefrom the earliest embryos to freshcorpses. The hope is that one day inthe future, patients will supplytheir own stem cells to generatecustomized raw material to helpheal. Those cells will be geneticallyreprogrammed to revert to a stemlikestate and then to reinventthemselves as a needed cell type.However, much research is stillnecessary to reprogram stem cellsin a way that is controlled, so as tonot cause cancer. The diversity ofpotential applications is staggering,with targets ranging from heart diseaseand spinal cord injuries, to cartilagerepair, liver repopulation,and even treating pattern baldness.We still must learn how to introduceand guide stem cells exclusivelyto areas in need, as well ashow to coax their progenitors toreplace damaged tissue, withouttriggering uncontrolled growth.Although the adult humanbody harbors sufficient sources ofstem cells to fuel many years ofresearch, the very best stem cellsfor research come from earlyembryos, at the ball-of-cells stage.Nurtured in laboratory glassware,these cells are revealing the neverbefore-seenbeginnings of diseases.What these enigmatic cells canreveal to us will fuel discovery anddevelopment of treatments that wecan’t yet even imagine.■Dr. Ricki Lewis, Fellow, Alden March Bioethics Institute,Albany Medical Center, has written several college biologytextbooks and more recently a novel Stem Cell Symphony,available at Amazon.com. Contact her atralewis@nycap.rr.comDr. Francis Barany, Director of the Hidden Cancer Project,and Professor of Microbiology at Weill Cornell MedicalCollege, was honored as Medical Diagnostics Researchleader, Scientific American 50, in 2004. Contact him atbarany@med.cornell.edu

16BOOK REVIEWSuite Francaise by Irène NémirovskyNemirovsky’s Unfinished SymphonySteve KlausnerAFrench family torn apart bythe terror of the Holocaust.A manuscript that lay forgottenin a suitcase for 40years. A flooded basement. A globalliterary sensation. Such are the circumstancesthat resuscitated thelong-lost novel Suite Francaise. Withits triumphant publication inFrance in 2004, the literary voice oflong-dead author Irène Némirovskywas resurrected to thunderousacclaim and no small measure ofcontroversy.Suite Francaise comprisesthe first two parts of whatNémirovsky envisioned as a fivevolumesaga of France at war andoccupied peace, modeled afterBach’s French Suites. The first part,Storm In June, begins as Germanforces mass outside of Paris in 1940.As panic-stricken citizens flee thecity for the surrounding countryside,the author documents theirordeal with the keen observationsof one who fled with them. An...she stuffed a leather suitcasewith her writings andentrusted it to her daughters.acclaimed novelist from the age of23, Némirovsky uses her prodigiousgifts to skewer the mostlyupper-class refugees and their haplessservants who scurry about theprovinces to devastating effect.In her words, the evacuationbecomes a tragedy of errors. Apriest is murdered by the thuggishadolescents in his charge. A charmingboulevardier steals petrol froman unsuspecting honeymoon couplein order to drive his preciouscollection of porcelain to safety. Apampered courtesan changespatrons as the fortunes of her“sponsors” ebb and flow.Book Two, Dolce, takesplace after the armistice betweenGermany and France brings somesemblance of order. It chronicles theoccupation in a rural village. As theGermans, polite and proper to afault, billet themselves in thehomes of the townspeople, resentmentsand tensions build. Will thenewlywed bride whose husband isa POW succumb to the charms of adashing Wehrmacht officer? Willthe sullen farmer defy the curfewand risk a bullet? Will there beenough food to make it through thewinter? The story concludes withthe German unit, about to returnhome, summoned instead to theRussian front. The village is emptiedof its occupying force. As theydepart, perversely, so does some ofthe community’s vitality.The author recalls theevents as only someone who hasexperienced them can. Unfortunately,she never lived to complete thelast three volumes, Captivity, Battlesand Peace. All of which makes thebook’s appendix every bit aspoignant as the novel, perhapseven more so. We learn that, unlikethe mostly French characters in hernovel, Némirovsky, her banker husbandMichel Epstein, and their twodaughters were already markedpeople. As Jews and immigrants,from Ukraine and Belgium respectively,Irène and Michel weredenied French citizenship in 1939.Even a last-minute conversion toCatholicism provided no protection.By 1940, the racial laws inVichy France were every bit ascruel as those in Germany. Jewswere officially barred from government,the armed forces, entertainment,arts, media, education, law,and medicine.For Némirovsky, this musthave been particularly galling.She rose to literary fame with thepublication of her first novel, DavidGolder. The story of a Kiev-born ragmerchant, the title character is variouslydescribed as “a fat little Jew”and “a grasping Jew.” The bookcontinued on page 22

17was made into an equally successfulfilm. When compared toNémirovsky‘s Golder, Philip Roth’sself-hating Alexander Portnoy takeson the qualities of a saint. What’smore, several of her other writingswere serialized in Gringoire, andCandide, two right-wing publicationsthat were virulently antiimmigrantand anti-Semitic. Manyof her pre-war friends would laterbecome Nazi collaborators andVichy zealots.This is not to say thatNémirovsky was unmindful of herown vulnerability to the gatheringstorm. In her notes she laments,“My God! What is this countrydoing to me? Since it is rejecting me,let us consider it coldly, let us watchas it loses its honor and its life.”By mid-1942, as thosearound her were swallowed up bythe Nazi terror, she stuffed a leathersuitcase with her writings andentrusted it to her daughters. Shewas arrested that summer anddeported to Auschwitz, where shedied of typhus.Desperate to find her,Michel, either in an appalling lackof common sense or in heroic desperation,penned a letter to OttoAbetz, the German ambassador toFrance: “Even though my wife is ofJewish descent, she does not speakof the Jews with any affectionwhatsoever in her works…it seemsto me both unjust and illogical thatthe Germans should imprison awoman who, despite being ofJewish descent, has no sympathywhatsoever — all her books provethis — either for Judaism or theBolshevik regime.”Within weeks, Michel wassent to Auschwitz and promptlygassed. The suitcase and the couple’stwo daughters were spiritedaway to a convent and cared for bysympathetic Catholics who riskedtheir own lives to shelter the girls.Forty years later,Némirovsky’s daughter, DeniseEpstein, opened the old suitcase forthe first time and leafed through itscontents. With that, her mother’sriveting portrayal of courage andsacrifice, suffering and cruelty,hope and despair found a publicand a purpose. It breathed new lifeinto a name and a legacy onceobliterated by hatred.■Suite Francaise by Irène Némirovsky.(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006)Steve Klausner is an advertising copywriter and anaward-winning screenwriter. A longtime member ofCentral Synagogue, Steve is also Chairman of theCommunications Committee.What the critics said about Suite Francaise“It is Némirovsky’s special gift towrite as a novelist about a humandrama in which she is a designatedvictim.” The New York Times“Remarkable.”Newsweek“A masterpiece ... ripped fromoblivion.” LeMonde“Testimonials of such power thathaving been written during, notafter, a war can be counted on thefingers of one hand.” L’Express“This extraordinary work of fictionabout the German occupation ofFrance is embedded in a real storyas gripping and complex as theinvented one.”The Washington Post“Némirovsky’s Suite Francaise,which might be the last greatfiction of the war, provides us withan intimate recounting of occupation,exodus and loss.”The Pittsburgh Post-GazetteBROKEN TABLETS continued from p. 14despair and give up hope. Wewere chosen by God to bring harmonyto this world. That’s a sacredtask we cannot reject or refuse.And children like you, who trust inGod and delight in His miracles,give us hope for renewal. So I mustgo back and beg God to forgive usand allow me to return to themountain and receive a new set oftablets inscribed with His covenant.”“And what shall we dowith the pieces of stone we collect?”the leader of the group asked.“I want each of you to keepone piece of stone and to guard itsafely. When you have children ofyour own, you must give yourpiece of stone to your firstbornchild. Each of them must pass thestone down through every generation.Then that piece of stone willserve as a reminder, that we have asacred task to bring harmony tothis world. Each generation mustteach the next. In that way youwill be bringing the pieces of stonetogether to remake the tablets ofGod’s covenant. Will you promiseme to do that?”“Yes, Moses,” all the childrenreplied.“But what happens to thepieces of stone we can’t find?” thelittle girl asked.“That’s a very good question,”Moses answered. “God willscatter the missing pieces throughoutthe world. Then one day everychild who does not have a piece ofstone will find one of the missingpieces and when that happens thewhole world will be renewed andreturned to harmony.”■Aunt MiriamAunt Miriam welcomes your comments and wouldlike to hear your ideas where we should look for thosemissing pieces of God’s covenant.Please write to her at editorhashiur@censyn.org.

18FICTIONAn Encounter with JobEric LevineImet Job one drab Decembermorning in Central Park. Hewas sitting alone on a bench,huddled into the upturned collarof his overcoat. The faceseemed familiar, but only as I drewnear, did it dawn on me who hewas. Media headlines had capturedthe mercurial rise of his businessempire and its most recent collapseinto bankruptcy. And as ifthat were not enough, he had losthis three children in a fire that haddestroyed his country mansion.“Where was He whenI needed Him? ”Wanting to comfort him,I sat down beside him. “I was sosorry to hear about your tragic losses,”I began. Job nodded severaltimes with tightly clenched jaw.Then he turned towards me and Inoticed the dark shadows beneathhis red, swollen eyes. He brokeinto a fit of coughing, turning awayto take a crumpled handkerchieffrom his coat pocket to wipe hismouth. He started to say somethingI could not make out, onlyto lapse into a heavy silence.Staring at the ground, hemuttered something; then lookedup at me with tears in his eyes.His hand reached out to grip mine.“Where did I go wrong?”he groaned. “Why was I deserted?That’s what I keep asking myself.Why was I deserted?” He intensifiedhis grip.“Who deserted you?” Iregretted the question as soon as Ihad asked it.“God!” he exclaimed fiercely.“Where was He when I neededHim!?”I was taken aback by hisreply. “Do you really believe Godinterferes in our personal lives?” Iresponded. “Do you think misfortuneoccurs through God’s indifference?”I knew of Job’s reputationas a conspicuously generous supporterof Jewish causes. But accordingto what I had read, his backgroundwas secular. Evidently, hehad embraced Judaism as a resultof his marriage into a wealthy,devout family that had fueled hisbusiness success.“Yes, I do!” he asserted.“That’s why we pray! Why elsesay all those personal prayers?Don’t we pray for things we wantto happen… like prosperity andgood health? Don’t we ask God tosend healing to those we cherish?Our prayers are full of personalneeds we want God to satisfy! Isn’tthat why we observe the mitzvot …to gain God’s pleasure?”“But still bad things dohappen to good people. How doyou explain that?” I replied.“Throughout our history even themost pious have died whileprotesting their faith in God.How does that square with a Godwho personally intervenes?”“You tell me!” Jobresponded.“I can only tell you what Ilearnt as a child from my lateGrandfather. He was a most saintlyperson. He taught me that Godwas the Source of Love and thatLove was the true reality of humanexistence. He taught me that if welove greatly, we come nearer toGod. And the nearer to God weget, the more we understand thetrue nature of life and of life hereafter.He spoke of a love that isselfless and transcendent.Remember when the Romans torturedRabbi Akivah to death forteaching Torah? As the iron combstore into his flesh he began to recitethe Sh’ma and as he did so, he criedout to his pupils that only nowdid he understand the true meaningof loving God with all one’sheart, with all one’s soul and withall one’s might. That’s whatloving greatly truly means, myGrandfather taught me. It’s a lessonI will never forget.”

19“But how does that answerthe question? What does love haveto do with a personal God?” Jobasked.“It has everything to dowith a personal God, because a truelove of God is the most personalrelationship you can ever experience.In one way you are right tosay that God is approachable,despite being infinite and omnipotent.But the approach must comethrough Love, indeed it can onlycome through Love. Performingthe mitzvot, giving to charity,attending services, reciting prayers,that by itself is not the way to havethe personal relationship you seek,or feel you are entitled to.”“So where did I gowrong?” Job asked, looking mestraight in the eye.“Only you can answer thatquestion, Job. But you need to behonest with yourself. Perhaps youmade mistakes in the way you createdyour business empire, perhapsbeing fiercely competitive was notthe best approach, perhaps youbecame so convinced of your invincibilitythat you took too manyrisks. Only you can tell. But don’tlook for blame, look for insights.And as for your daughters, youcan’t blame yourself or God for thefaulty electric wiring that causedthe fire.”He released his grip of myhand and stood up. “You havegiven me a lot to think about,” hesaid. Then he turned and walkedslowly away.Some two years later Icame across Job sitting on the samebench in Central Park. It was awarm spring day. He called me over.He was looking fit and relaxed.“I was hoping our pathswould cross again,” he said. “Youknow, I often come here. It givesme a chance to think. Just sittinghere reminds me of what yourGrandfather taught you.”“I’m pleased to see youlooking so well,” I replied. “Howis everything going?”“Come and sit down andI’ll tell you.” As I sat down he puthis arm around my shoulder withan affectionate hug. “You know,after we last met, I took a long walkthrough the Park. And mullingover what you had said, I realizedthat I was totally absorbed in myown self-pity, without any thoughtabout my wife’s grief at losing thechildren. How I could have beenso selfish, I really don’t know. I’mnot sure whether I really loved mywife when we married, but bysharing our grief we drew closerthan we had ever been, and the sortof love you spoke of began to blossom.We now have a little boy, aSabbath child, and another baby onthe way. My wife says they aregifts from God.”“I restarted my businessand the strangest thing was that thebanks I thought wouldn’t want toknow me, rushed to give me theirsupport. The business is going wellbut I keep it private and in perspective.No more ego trips. But themost beautiful thing of all, whichyour Grandfather would haveappreciated, was a visit my wifeand I paid to one of her favoriteuncles, whose health was failingand who had recently becomeblind. As we entered his bedroomhe held out his arms, with a beamingsmile on his face. Before wecould even greet him, he told usthat he could feel God’s presencein the room, embracing us.At that moment I began to understandwhat your Grandfatherhad meant.”■Eric Levine is a transnational corporate lawyer, a foundingprincipal of Millenia Capital Partners, an investment advisoryfirm and CEO of its inner-city redevelopment division.Reading Suggestion:Mitchell, Stephen, trans. The Book of Job (New York:HarperPerennial, 1992)

20ESSAYReflections on the New Prayer BookRenewal of LiturgyRabbi Sarah H. Reines“Ma tovu ohalecha Yaakovmishk'notecha Yisrael Howgoodly are your tents, OJacob, your dwellingplaces, O Israel,” is the first line ofthe opening prayer of every morningservice. It is taken from a passagein Numbers 24 when a foreignprophet, Balaam, upon orders ofhis king, sets out to curse theIsraelites, enemies of his people.Standing on an embankment overlookingtheir tents and seeing howthey lived together simply and ingoodness, his curse is transformedinto blessing.Ma Tovu may not be ascompelling as the sh’ma, as visionaryas the aleinu or as stirring as themourner’s kaddish, but I find it tobe the most instructive of all ourliturgy regarding the purpose ofprayer. It reminds us that theimportance of worship does not lieonly in how we experience theservice but also in how we emergefrom it. We enter the synagogue,bruised by the realities of daily life,but, like Balaam, we leave itrenewed: more attuned to the simplewonders around us and closerto the best within us.If the purpose of prayer isrenewal, it is fitting that the developmentof Jewish liturgy hasundergone a continual process ofrenewal through the centuries,from the Biblical era until today.Balaam’s spontaneous outburstresembles the typical form ofexpression of our most ancientprayers. In the Torah, blessingsand prayers do not follow a specificformula. Some are a direct requestto God. Eleazar, Abraham’s non-Israelite servant, prays to Adonaithat the woman intended forAbraham’s son Isaac, will somehowbe revealed to him. Moses offersthe poignantly simple plea thatGod cure his sister, Miriam, fromleprosy: “El na rafa na la — God,please heal her.” These prayersand others represent universalhuman longings that God willrespond to individual needs....the reforming of Jewishworship began asearly as the destructionof the Temple.The Biblical era’s regimentedcommunal worship took theform of sacrifice, which followed acarefully laid out process involvingspecific times, offerings, actions,and participants. The destructionof the second Temple in 70 CE alsodestroyed the sacrificial rite. Wewere now a dispersed nation withouta core worship ritual to unify us.That our history didn’t end thereis a result of the ingenuity and perseveranceof the first rabbis.Sages of the early centuriescreated a structure for Jewish worshipthat could respond to ourdecentralization but would alsobind us together as one people.They determined a set of themes,organized in a logical sequence:preparation for prayer, affirmationof belief, supplication to God, concludingprayers of gratitude andpraise. Certain Biblical passages,like the sh’ma, became fixtures ofTop right: Central Synagogue’s new prayer book,Friday evening service and title page.Below: Title page of the first Reform prayer book,published in Hamburg, Germany in 1819.

21this evolving rite, as did the practiceof reading Torah portions.However, individual Jews had thefreedom to express their prayers intheir own words, using their vernacularlanguage. From thisemerged the dialectic of Jewishprayer: specific structure (keva) thatallowed for outpouring of the heart(kavanah). We depend upon kevafor a framework that will defineour tradition and unify us. At thesame time, space for kavanahinsures that worship will breathewith self-expression and relevance.Both are necessary elements formeaningful, communal worship, butthe perfect balance has often provedelusive and subjective, especiallyonce liturgy was written down.One generation passeddown its practice to another; individualcreativity lessened as localcustoms and prayers evolved.People of a specific communitywould all bow at the same point intheir service; a certain liturgicalphrase or poem became set amongthat group of worshippers. Asmore traditions developed, peoplesought validation of their authenticity.By the8th century, theJewish Academyof Sura inBabylonia hadattained tremendousauthority.These sages,knownas Geonim(singular, Gaon), received inquiriesfrom different Jewish communitiesasking about the legality and permissibilityof various liturgical andritual customs. Not surprisingly,responses reflected BabylonianJewish practices. In 857 CE, theleading Gaon, Amram bar Sheshna,penned what may be consideredthe first Jewish prayer book, orsiddur. It contained services forordinary days and holidays, lifecycleceremonies as well as commentaries,directing people how tooffer prayers and warning aboutincorrect practices.This Siddur preceded theinvention of the printing press.Though few Jews owned a copy,many rabbis and chazzanim (cantors)used their own to lead services.Different siddurim were written, butAmran’s remained the most influential,not only in Babylon, but alsolater in Western Europe and eventuallyeven in America, especiallyafter printed copies became available.However, the process of liturgicalrenewal continued. Elementsof the prayer service fundamentalto us today were added in latergenerations, such as the KabbalatShabbat service, born from the 16thcentury mystics of Safed, and yizkormemorial prayers, created inresponse to the Crusades and 17thcentury Polish pogroms.Although the reforming ofJewish worship began as early asthe destruction of the Temple, theworship rituals of our Reformcontinued on next page

22LITURGY continued from preceeding pagemovement are far more recent.Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, one of thefounders of the American Reformmovement, authored MinhagAmerica, a siddur he hoped wouldunify all American Jewry. RabbiWise’s grand vision was not realized;in its attempt to reach out tothe largest number of Jews, hisprayer book did not depart muchfrom siddurim of the past; it wasrejected by the children of Germanimmigrants who were seeking aritual that would reflect the tremendouschanges in their own lifecircumstanceand religious practice.The Union Prayer Book followedin 1895, representing thepractices and ideologies of classicalReform. It removed prayers seekinga return to Zion and insteademphasized universalism, rejectingthe notion of Jews as a chosen people.The UPB stressed decorumand formality in worship, clearlydefining the roles and participationof rabbi, cantor, choir, and congregation.Keva was dominant;kavanah was nearly impossible toattain.Gates of Prayer, published in1975, responded to the creativityand ethnic pride of the 1960s aswell as to the major historicalevents of the past decades. ThisSiddur used more Hebrew thanUPB and included ten differentFriday night services, all reflectingvarious themes. It containedadditional services for HolocaustRemembrance Day and IsraeliIndependence Day, as well asmeditations and new prayers sprinkledthroughout. Keva was nowminimized; kavanah was a goal,but it was too scripted to be highlyeffective.The small, gray edition ofGates of Prayer which we have usedat Central Synagogue for the pastdecade, was meant as a temporaryprayer book that would providegender neutral language until thenext version became available. Wehave now begun using the recentlypublished Mishkan T’Filah, whichseeks to balance keva, and kavanah.It has a unique format, with eachprayer spread over a double page.The right side gives the Hebrewprayer, fully transliterated andclosely translated (keva) while theleft side contains poems, creativeprayers and writings explicatingthe theme ( kavanah). Congregantscan move through the service eithertogether as a community, followingthe traditional prayer, or as individuals,focusing on its interpretiveexpression. Mishkan T’Filah hasalso reclaimed Amram barSheshna’s addition of descriptionsand teachings, which permits worshippersto learn more about theelements of the service and the ritualpractices associated with specificprayers.Jewish survival, bothphysical and spiritual has alwaysdepended upon our ancestors’ability to renew and reinvent themselves,both as individuals and asa people. We have inherited thatcharge as well. Though change issometimes frightening because wefind comfort in the familiar, weshould not think of Mishkan T’Filahas a radically new prayer book.It is but another step in the evolutionof our human desire to reachout for what is sacred and of ourJewish need to affirm traditionwithin the embrace of community.Siddurim reflect the circumstancesinfluencing our ritual, butultimately they are springboardsfor our own offerings to God. ■Letters to the EditorWe welcome your comments and suggestions at editorhashiur@censyn.org“Thank you for HaShiur, easily the most stimulatingSynagogue journal I have ever seen!”Rabbi Jeremy Rosen,London“Kudos for producing a journal of ideas that managesto be interesting, lively, well-written, utterly uncondescendingand handsomely designed. It is a stunningachievement.”Ravelle Brickman“Congratulations on the new issue, new format…Critique: no humor (Jews do laugh or at least chuckle)...Suggestion: publication worthy of greater visibility.”Jerry Pickman“The range of material (reviews, fiction, reflections) andthe remarkable art work interspersed made for a richpanorama on Jewish memory. Judy and I are pleased tohave been a part of this new editorial and design visionfor HaShiur.Neil Grill andJudy Smith

EDITORIAL Hashiur / Spring 2008Rhythms of Renewal23HaShiurA JOURNAL OF IDEASToday young Jews are moving back to the LowerEast Side. Though these new urbanites return tothe roots their families first set down at the tip ofManhattan and resume their worship in the sametemple, they are not living in crowded tenements andtheir synagogue sparkles like a jewel freed from thedust of ages. What was once the epicenter of Jewish lifein New York is now a crucible of polyglot, multi-cultural,multi-religious coexistence. While Jews observe thesacred precepts of the Sabbath, their Asian andHispanic neighbors are busy pursuing commercialenterprise, and restaurants, bars, galleries, and boutiquescater to the devotees of cool at all hours of theday and night. Diversity has replaced homogeneity; thereturn to the place of their forebears finds it changed,altered by the imprint of others, which subtly impactsthe newly burgeoning Jewish life. This current migrationepitomizes the quintessential, concurrent rhythmsof renewal: continuity, cyclical recurrence and change.Continuity focuses on the preservation of thepast; its gaze is directed backward, following the linearflow of time, intent on keeping the past alive in thepresent and renewing the spirit of old, to imbue it withnew life commensurate with contemporary life. Ourpsychological need for continuity is foundational; intimatelylinked to our identity, it generates a sense ofsecurity and comfort as we build on the pillars of thepast. The designation of part of the Lower East Side ashistoric district, for example, and the efforts of variouspreservation coalitions are testimony to the forces ofcontinuity that enable the renewal of the past in thepresent. Likewise, the observance of spiritual and culturaltraditions is born from the desire for perpetualcontinuity, which in itself becomes a form of consecrationof the old in the new.Cyclical recurrence attests to permanencewithin flux; its gaze revolves, bending the linear flow oftime as it follows the cycle of the seasons, the days ofthe week, the hours of the day and night, the rising andsetting of the constellations. The rhythm of their perpetualrecurrence reassures us that, no matter what happens,a new day will dawn. Observing, for example, therituals of the Sabbath, of Passover and Rosh Hashanah,of blessing the rise of the new moon each month, and,during Shavuot, the celebration of entering thecovenant with God as a re-entering of the springtime ofour relationship. All these are markers of cyclicalSalvador Dali, The Persistence of Memoryrenewal, islands of permanence in the river of time.Like the awareness of continuity, cyclic recurrence reassuresand stabilizes.Change documents the difference wrought bythe flow of time; its gaze is directed forward, acknowledgingthat what was in the past, no longer appearsquite the same in its present iteration, and will continueto exhibit new forms in the future. No sunrise is exactlyas the one before, no ritual observance, no matterhow prescribed, is ever the same. But as we seek torenew the past in the present and are buoyed by thesigns of cyclical recurrence, we also have to concedethat time has wrought change. For that reason weupdate our prayer books or add more music to theservice. The changing needs of the present constituentsinfluence everything, from the restoration of synagoguesto the revitalization of neighborhoods. TheLower East Side perfectly showcases this kind of adaptivefluidity that is the hallmark of change.The rhythms of renewal are dynamic; theyrestore, repair and revive; their current carries us fromthe past to the future, while their cyclical aspect assuresus that the past is not lost. But above all, they teach ustwo lessons, both inherent in the rhythm of change:We cannot step into the same river twice and we haveto embrace difference, which is the foundation of tolerance.As we observe the modulations wrought by therhythms of renewal on the remainder of the past, wecelebrate its rebirth in new form, as the sapling froma sacred tree in a changing grove.■Amala Levine, Editor

AN ARCHITECT’S JOURNEY continued from p. 13who want to live there and worshipin the restored sanctuary ofChasam Sopher like their forefathersdid. At the same time, it isalso one of the hottest neighborhoodsin New York, in terms ofrestaurants, boutiques andnightlife.What I love about NewYork is its density and diversity, allthese things happening together tomake it work as a city. In St. Paul,this would not be possible. I likegoing into neighborhoods that areon the edge; I like to be involvedin providing the stimulus forchange and in visualizing an imageof what the area could or shouldbecome. The exciting thing iswaiting for a vision to emerge. ■Marvin H. Meltzer, AIA, is a founding partner ofMeltzer/Mandl Architects, PC, which has been responsiblefor the creation of more than 10,000 units of luxury andaffordable housing in the greater New York Metropolitanarea. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award by theNew York Society of Architects as well as a series of designawards for innovative work throughout NYC. His designfor Melrose Court in the South Bronx was named the bestin the country by the National Association of HomeBuilders.Reading Suggestions:Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities,(New York, Modern Library: 1993)Charles Orlebeke, New Life at Ground Zero: New York,Home Ownership, and the Future of American Cities,(New York: Rockerfeller Institute Press Publications, 1997)OFFICERSPresidentHoward F. SharfsteinVice-PresidentDavid B. EdelsonVice-PresidentJuliana MayVice-PresidentLaura J. RothschildVice PresidentPhillip M. SatowTreasurerNeil MitchellSecretaryJohn A. GoliebHonorary Presidents:Samuel BrodskyMartin I. KleinSamuel M. WassermanMichael J. WeinbergerAlfred D. YoungwoodBoard of Trustees:Alan M. AdesKaren ChaikinEdith FassbergJanet H. FellemanRichard A. FriedmanLinda GordonAlan R. GrossmanMarni GutkinKenneth H. HeitnerPeter JakesCarol KalikowCary A. KoplinDavid L. MooreFrederic PosesRichard G. RubenBruce D. SchlechterIrving SchneiderWendy SiegelEmily SteinmanStephanie StiefelKent SwigMarc WeingartenDavid ZaleHonorary Trustees:Lester Breidenbach, Jr.Geraldine FriedmanDr. J. Lester GabriloveClergy:Rabbi Peter J. RubinsteinRabbi Sarah H. ReinesCantor Angela WarnickBuchdahlRabbi Ruth A. ZlotnickCantor Elizabeth SacksCantor EmeritusRichard BottonExecutive Director:Livia D. Thompson, FTALetters To the Editor(see page 22)please emaileditorhashiur@censyn.orgHASHIUR A Journal of Ideasis published 3 times a year by Central Synagogue,123 East 55th Street, New York, NY 10022-3502Editorial Committee:Rabbi Ruth Zlotnick, Amala and Eric Levine,Steve Klausner, Rudi WolffEditor: Amala LevineDesigner and Picture Editor: Rudi WolffProduction Editor: Terry JenningsPicture CreditsCover: Cluster of cells called blastomers.Photo courtesy of Advanced Cell Technology Co.Page 2: from The Jewish World(New York: Harry N. Abrams Publishing, 1979)Page 3: Meeting of Ruth and Boaz, Marc Chagall, fromthe series Drawings from the Bible, Lithograph.Page 4: Dead Sea photos, ©Marion Kaplan 2008Page 5:The Nasdaq Stock Market, Inc. andThe Hebrew University, JersusalemPage 6: Destruction and Hope, Paul Klee, 1916,Lithograph, Museum of Modern ArtPages 8-9:World Union of Progressive JudaismPages 10-11: Drawings, Ben BaxtPages 12-13:Talk Bronx, NYC andMeltzer/Mandl Architects, PCPage14: Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law,Rembrandt van Rijn1659, Gemaldegalerie, BerlinPage 16: Suitcase, rangefinderforum.comPages 18-19: Photographer unknownPages 20-21: Siddur 1819, Library of The JewishTheological Seminary, Mishkan T’Filah,all photos R.WolffPage 23: The Persistence of Memory, Salvador DaliMuseum of Modern Art / Art Resources, NYNo material may be used without prior writtenpermission from Central Synagogue.123 EAST 55TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10022-3502NON-PROFITORGANIZATIONU.S. POSTAGE PAIDNew York, N.Y.Permit No. 8456